To the Editor:

Older persons living in long-term care facilities are underrepresented in studies on the clinical spectrum of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), especially regarding the broad range of COVID-19 signs/symptoms and course over time. In the context of advance care planning and, in the Netherlands, older care physicians providing nursing home care, diagnostics, and optimal supportive care are mostly provided within the nursing home. In this setting, COVID-19 testing is dependent on either signaling signs/symptoms via medical history, observation, and physical examination, or known contact with a confirmed case. However, an atypical disease presentation and course, as signaled by initial studies in hospitalized older persons, may hamper identification of COVID-19 cases.1, 2, 3 Our aim was to gain insight into the broad spectrum of signs/symptoms, disease course, and outcome in nursing home residents with COVID-19.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study among residents with confirmed COVID-19 in the period March to April 2020 at 4 long-term care organizations in the Netherlands (see Supplementary Methods). Electronic health records were searched for demographics; comorbidity; 22 signs/symptoms, including clinical criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) case definitions from March and August 2020;4 , 5 dates on first registration; decrease in or full recovery from signs/symptoms; and disease outcome. For registered signs/symptoms, we assessed prevalence at presentation; period prevalence; and time to onset, decrease, and full recovery. We explored differences in characteristics between deceased and recovered residents.

Results

In total, 88 of 94 eligible residents were included (see Supplementary Table 1).

Spectrum of Signs/Symptoms

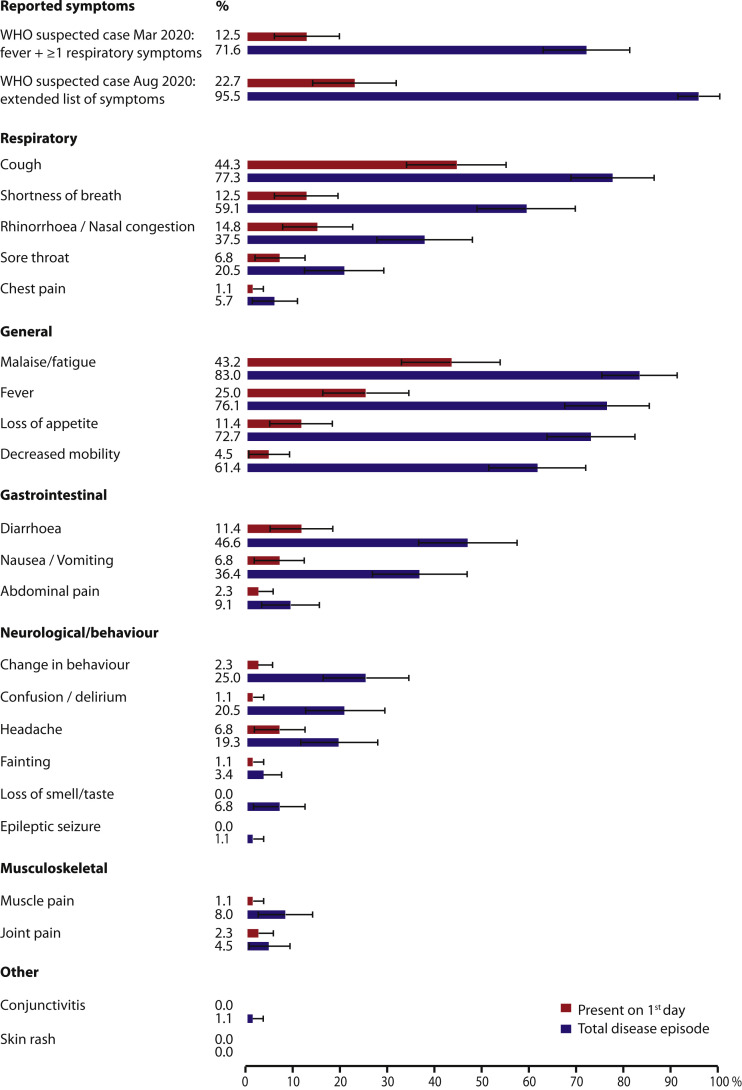

Fever and respiratory symptoms, especially cough and shortness of breath, were the most frequently registered signs/symptoms, at presentation as well as over the disease course. Nevertheless, only up to 63 residents [71.6%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 62.6%–81.0%] fulfilled the clinical criteria of the initial WHO case definition (March 2020). Using the current definition (August 2020), up to 84 residents (95.5%, 95% CI 91.1%–99.8%) would have fulfilled the criteria (Figure 1 ). Frequently reported signs/symptoms from this list are of a more general nature (up to 83.0% malaise/fatigue; 72.7% loss of appetite/decreased intake) or related to the gastrointestinal tract (46.6% diarrhea; 36.4% nausea/vomiting) or altered mental status (20.5% confusion/delirium; 25.0% behavioral change). Behavioral change includes agitation/wandering (13.6%), mood changes/anxiety (5.7%), and apathy (4.5%). In addition, 61.4% of the residents experienced reduced mobility (20.5% unstable walking and/or falling; 40.9% becoming bedridden).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of reported symptoms on the first day and over the course of COVID-19, that is, the period prevalence. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Clinical Course

Cough and malaise/fatigue were mostly present at presentation, that is, after median 0 days [interquartile range (IQR) 0–4] (see Supplementary Table 2). Fever developed mostly within 1 day (IQR 0–4), peaked with median 38.7°C (IQR 38.4–39.2°C, maximum 41.6°C) after 1 day (IQR 0–5) and disappeared after 3 days (IQR 1–9). Other respiratory and general symptoms were observed after median 2 to 3 days and mostly disappeared after 2 to 3 weeks. Gastrointestinal complaints appeared to occur later, after median 4 to 5 days, and to disappear within a week.

Oxygen therapy was started in 49 (55.7%) residents after median 5 days (IQR 3–8), for a period of 9 days (IQR 1–24) and with maximum supplementation after 1.5 days (IQR 0–5). Lowest oxygen saturation during supplementation was median 89% (IQR 84–93).

Disease Outcome

At data collection 32 residents (36.4%, 95% CI 26.3%–46.4%) had died at median 10.5 days (range 6–96) after first signs/symptoms; 30 died of COVID-19 after 6 to 23 days, and 2 from general health decline afterward. Full recovery was registered in 47 (53.4%) residents after median 26 days (range 4–47) and partial recovery in 9 (10.2%) after 50 days (range 39–128) follow-up.

Several signs/symptoms were associated with death, including higher fever and lower oxygen saturations during supplementation: median 38.9°C (IQR 38.4–39.6°C) versus 38.5°C (38.2–38.8°C) and 85% (79%–88%) versus 91% (88%–93%) (see Supplementary Table 3). Male residents and residents with dementia or another chronic neurological disorder were at increased risk for 4-week mortality, with the following hazard ratios in multivariable Cox regression analysis: 2.02 (95% CI 0.93–4.40), 2.22 (95% CI 0.97–5.08), and 1.97 (95% CI 0.89–4.39).

Conclusions

Our findings underline the importance of awareness of the broad spectrum of signs/symptoms to identify nursing home residents with COVID-19. A large proportion of these residents (28.4%) did not develop fever with ≥1 respiratory symptoms, thereby not fulfilling the initial WHO case definition. The observed spectrum of signs/symptoms includes atypical symptoms and geriatric syndromes (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms, confusion/delirium, behavioral change, and decreased mobility). Therefore, the current, extended WHO case definition covers our cases better (95.5%). Because we actively searched for this broad range of signs/symptoms (at presentation as well as over the disease course), our results complement studies on symptomatology in nursing home residents.6, 7, 8, 9

The observed mortality rate (36.4%) and the increased 4-week mortality risk in male residents and residents with dementia are confirmed by recently published studies.7, 8, 9 These findings may serve as point of departure for future studies on prognostic factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following health professionals for their assistance in the study set-up and data collection: Coran Ongering and Michelle Nijhuis-Geerdink from TriviumMeulenbeltZorg and Wanda Rietkerk from Zorggroep Noorderboog; and the following for their assistance in data collection: Martin Ketellapper from Noorderbreedte and Christine de Boer from Meriant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research project was performed within the University Network of Elderly Care – UMCG, which is financially supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The sponsor has had no other role in this study than offering financial support.

SUPPLEMENT – To Research Letter “Clinical presentation and course of COVID-19 in nursing home residents: a retrospective cohort study” Supplementary Methods

Study Design and Setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study in nursing home residents with COVID-19 during the first COVID-19 wave in the Netherlands (March–April 2020). Five health professionals from 4 long-term care organizations in the north and east of the Netherlands, all members of University Network of Elderly Care, collected data from electronic health records.

Exemption from full medical ethical review was received from the Medical Ethics Review Board of University Medical Centre Groningen, because the research falls outside the scope of the Dutch Medical Research with Human Subjects Law. The health professionals obtained informed consents from the residents or legal representatives if necessary and possible, in accordance with the Dutch Medical Treatment Agreement Act. The researchers had no access to health records, encryption keys, and other directly identifiable data.

Study Population

Nursing home residents were eligible if they (1) stayed at a ward for long-term stay or geriatric rehabilitation in the period March to April 2020, and (2) had confirmed COVID-19, that is, a positive reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 on nasopharyngeal swab.

Data Collection

Participating health professionals extracted data from the electronic health records with a standardized electronic data collection form, which had been developed in collaboration.

Collected data consisted of the following: demographics (age, sex); type of stay (long-term, geriatric rehabilitation); comorbidity (chronic conditions, mobility, body mass index, actual smoking); dates and results of COVID-19 tests; date of first registered sign/symptom (ie, day of presentation); a prespecified list of 22 signs/symptoms based on the WHO case record form; dates on first registration, decrease or full recovery of signs/symptoms; related physical parameters (eg, highest body temperature, lowest oxygen saturation); received supportive care (eg, oxygen therapy); and disease outcome (hospitalization, death, partial or full recovery).

Outcomes

For each sign/symptom, the prevalence was calculated for the day of disease presentation and for the total period (ie, period prevalence). In addition, we estimated how many residents fulfilled the clinical criteria of the WHO suspected case definition: (1) the definition from March 2020, that is, fever combined with ≥1 respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath, rhinorrhoea/nasal congestion, sore throat), and (2) the definition from August 2020, that is, either the combination of fever and cough, or ≥3 of the following signs/symptoms: fever, cough, general weakness/fatigue, headache, myalgia, sore throat, rhinorrhea/nasal congestion, dyspnea, anorexia/nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, altered mental status (combination of our categories confusion/delirium and behavioral change).7

To describe the clinical course of the disease, we estimated the rates of death and partial or full recovery, total disease duration, and for individual signs/symptoms time from presentation to onset and, if applicable, time from onset to decrease and full recovery, as noted in the health record.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the following: the baseline characteristics; the prevalence of signs/symptoms and the time to onset, decrease, and full recovery; and disease outcome. Categorical variables are presented with their absolute frequency and frequency in %. Continuous variables, which were not normally distributed, are presented with median and IQR or full range. Differences in baseline characteristics and signs/symptoms between deceased and recovered residents were tested with the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Subsequently, baseline characteristics that were potentially associated with time to death were tested in a Cox regression model; first in a univariable model and then combined, together with age, in a multivariable model. All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES TO THE RESULTS SECTION

Supplementary Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included COVID-19–Positive Nursing Home Residents (n = 88) and Disease Outcome

| Characteristic | All |

Recovered (Fully or Partially) |

Deceased |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 88) | (n = 56) | (n = 32) | |

| Age (y), median (min. – max.) | 83.5 (65 – 97) | 83.5 (65 – 97) | 83.5 (69 – 97) |

| Sex (male), n (%)∗ | 24 (27.3) | 11 (19.6) | 13 (40.6) |

| BMI, median (min. – max.) | 25.1 (17.8 – 43.5) | 25.3 (17.8 – 43.5) | 24.7 (20.1 – 33.4) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), n (%) | 12 (19.7) | 10 (25.0) | 2 (9.1) |

| Type of stay, n (%) | |||

| Long-term stay | 74 (84.1) | 46 (82.1) | 28 (87.5) |

| Geriatric rehabilitation | 14 (15.9) | 10 (17.9) | 4 (12.5) |

| Chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| COPD | 13 (14.8) | 7 (12.5) | 6 (18.8) |

| Asthma | 3 (3.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (3.1) |

| Coronary heart disease | 44 (50.0) | 24 (42.9) | 20 (62.5) |

| Heart failure | 17 (19.3) | 12 (21.4) | 5 (15.6) |

| Stroke | 20 (22.7) | 13 (23.2) | 7 (21.9) |

| Hypertension | 51 (58.0) | 33 (58.9) | 18 (56.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (22.7) | 13 (23.2) | 7 (21.9) |

| Cancer, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer | 15 (17.0) | 12 (21.4) | 3 (9.4) |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 (2.3) | 2 (3.6) | – |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17 (19.3) | 12 (21.4) | 5 (15.6) |

| Dementia∗ | 50 (56.8) | 27 (48.2) | 23 (71.9) |

| Chronic neurological disorder, excluding dementia∗ | 20 (22.7) | 8 (14.3) | 12 (37.5) |

| Current smoking (yes), n (%)† | 7 (10.0) | 6 (13.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Mobility before COVID-19, n (%) | |||

| Bedridden | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.8) | – |

| In wheelchair | 29 (33.0) | 17 (30.4) | 12 (37.5) |

| Walking with physical help or supervision | 19 (21.6) | 10 (17.9) | 9 (28.1) |

| Independent with or without mobility aid | 39 (44.3) | 28 (50.0) | 11 (34.4) |

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Statistically significant difference between deceased residents and fully or partially recovered residents in χ2-test (P < .05).

Values based on the number of residents with available data: data are missing on body mass index for 26 residents and on smoking for 18 residents.

Supplementary Table 2.

The Course of the 12 Most Frequently (≥20%) Reported Signs and Symptoms, Per Tract∗

| Sign/symptom | Day Start |

Duration Until Decrease (d) |

Duration Until Full Recovery (d) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | n | Median (IQR) | |

| Respiratory | ||||||

| Cough | 68 | 0 (0–4) | 38 | 9 (2–16) | 34 | 18 (7–26) |

| Shortness of breath | 52 | 3 (1–5) | 26 | 7 (1–12) | 18 | 15 (5–21) |

| Rhinorrhea/nasal congestion | 33 | 2 (0–9) | 8 | 5 (1–8) | 8 | 6 (1–15) |

| Sore throat | 18 | 2 (0–7) | 3 | 3 (–)† | 4 | 12 (–)† |

| General | ||||||

| Malaise/fatigue | 73 | 0 (0–4) | 34 | 12 (6–20) | 28 | 17 (10–25) |

| Fever | 67 | 1 (0–4) | – | Not applicable | 51 | 3 (1–9) |

| Loss of appetite/decreased intake | 64 | 3 (1–7) | 28 | 8 (3–13) | 27 | 13 (7–19) |

| Decreased mobility | 54 | 3 (1–6) | 17 | 12 (4–17) | 11 | 17 (3–22) |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 41 | 4 (1–7) | 24 | 3 (1–13) | 22 | 7 (1–19) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 32 | 5 (2–8) | 21 | 1 (1–12) | 19 | 1 (1–16) |

| Neurological/behavior | ||||||

| Change in behavior | 22 | 3 (1–5) | 10 | 5 (3–8) | 9 | 8 (4–11) |

| Confusion/delirium | 18 | 8 (4–10) | 8 | 5 (3–19) | 6 | 11 (3–24) |

The durations until decrease and full recovery of signs and symptoms are based on a smaller group of residents, because a group of residents died before decrease and/or full recovery.

No IQR available because of the small number of observations.

Supplementary Table 3.

Comparison of the 12 Most Frequently Reported Symptoms and Related Signs During the Course of COVID-19 Between Recovered and Deceased Residents

| Symptoms and Signs∗ | Recovered (Fully or Partially) |

Deceased |

P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 56) | (n = 32) | ||

| Clinical criteria suspected COVID-19 case (WHO) | 52 (92.9) | 32 (100) | .12 |

| Respiratory symptoms and signs | |||

| Cough | 47 (83.9) | 21 (65.6) | .05 |

| Shortness of breath‡ | 29 (51.8) | 23 (71.9) | .07 |

| Highest respiratory rate (/min), median (IQR) | 28 (24–31) | 33 (24–46) | .04 |

| Lowest oxygen saturation on room air (%), median (IQR) | 89 (85–93) | 85 (80–89) | .01 |

| Supplemental oxygen therapy | 20 (69.0) | 17 (73.9) | .70 |

| Lowest oxygen saturation on supplemental oxygen (%), median (IQR) | 91 (88–93) | 85 (79–88) | .02 |

| Rhinorrhea/nasal congestion | 21 (37.5) | 12 (37.5) | 1.00 |

| Sore throat | 13 (23.2) | 5 (15.6) | .40 |

| General symptoms and signs | |||

| Malaise/fatigue | 43 (76.8) | 30 (93.8) | .04 |

| Fever‡ | 39 (69.6) | 28 (87.5) | .06 |

| Highest body temperature (°C), median (IQR) | 38.5 (38.2–38.8) | 38.9 (38.4–39.6) | <.01 |

| Loss of appetite/decreased intake | 32 (57.1) | 32 (100.0) | <.01 |

| Decreased mobility | 24 (42.9) | 30 (93.8) | <.01 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | |||

| Diarrhea | 26 (46.4) | 15 (46.9) | .97 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 16 (28.6) | 16 (50.0) | .04 |

| Neurological/behavioral symptoms | |||

| Change in behavior | 12 (21.4) | 10 (31.3) | .31 |

| Confusion/delirium | 8 (14.3) | 10 (31.3) | .06 |

Variables are presented as frequencies, n (%), unless indicated otherwise.

χ2-test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Related variables are presented for the group of individuals with the sign/symptom concerned, that is, shortness of breath or fever.

References

- 1.Lithander F.E., Neumann S., Tenison E. COVID-19 in older people: A rapid clinical review. Age Ageing. 2020;49:501–515. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knopp P., Miles A., Webb T.E. Presenting features of COVID-19 in older people: Relationships with frailty, inflammation and mortality. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11:1089–1094. doi: 10.1007/s41999-020-00373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niu S., Tian S., Lou J. Clinical characteristics of older patients infected with COVID-19: A descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104058. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Global surveillance for COVID-19 caused by human infection with COVID-19 virus: Interim guidance, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331506 Available at:

- 5.World Health Organization Public health surveillance for COVID-19: Interim guidance, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333752 Available at:

- 6.Shi S.M., Bakaev I., Chen H. Risk factors, presentation and course of coronavirus disease 2019 in a large, academic long-term care facility. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1378–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livingston G., Rostamipour H., Gallagher P. Prevalence, management, and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infections in older people and those with dementia in mental health wards in London, UK: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:1054–1063. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30434-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutten J.J.S., van Loon A.M., van Kooten J. Clinical suspicion of COVID-19 in nursing home residents: Symptoms and mortality risk factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1791–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bielza R., Sanz J., Zambrana F. Clinical characteristics, frailty and mortality of residents with COVID-19 in nursing homes of a region of Madrid. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;11:33417840. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]