Abstract

Introduction

COVID-19 is a multi-system infection which predominantly affects the respiratory system, but also causes systemic inflammation, endothelialitis and thrombosis. The consequences of this include renal dysfunction, hepatitis and stroke. In this systematic review, we aimed to evaluate the epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of all studies published between November 1, 2019 and July 8, 2020 which reported on patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19.

Results

326 studies were screened, and 30 studies reporting findings from 55,176 patients including 899 with stroke were included. The average age of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 65.5 (Range: 40.4–76.4 years). The average incidence of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 1.74% (95% CI: 1.09% to 2.51%). The average mortality of stroke in COVID-19 patients was 31.76% (95% CI: 17.77% to 47.31%). These patients also had deranged clinical parameters including deranged coagulation profiles, liver function tests, and full blood counts.

Conclusion

Although stroke is an uncommon complication of COVID-19, when present, it often results in significant morbidity and mortality. In COVID-19 patients, stroke was associated with older age, comorbidities, and severe illness.

Key Words: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Stroke, Cerebrovascular accident, Complication

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to cause disruption nine months after it began in Wuhan, China.1 Although COVID-19 predominantly affects the respiratory system, studies in those with severe infections have broadened our understanding of COVID-19 as a multi-system inflammatory disorder with effects on the neurological system as well. Neurological complications associated with COVID-19 include mild complications such as headache and anosmia, and more serious complications such as encephalitis and stroke.2

Stroke appears to be an infrequent complication of COVID-19 but when it occurs can result in significant morbidity and mortality.3 Systematic reviews which consolidate findings of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 are scarce,3, 4, 5, 6 examining few primary sources with limited coverage of demographic factors and clinical parameters of patients. To address this gap in literature, we conducted a systematic review to more comprehensively evaluate the epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.7 A search string was developed to identify original research studies reporting clinical features and treatment outcomes of patients with stroke as a complication of COVID-19 [Supplementary Table S1]. Stroke was defined as a reduction in blood flow to the brain causing infarction. For this analysis, only studies reporting ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes were included. All strokes were diagnosed radiologically, such as by CT or MRI scans of the brain. The search was applied to the following four electronic databases: Pubmed, Ovid Medline, Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Searches were performed for each database on July 8, 2020. Limits were applied to the search to identify studies published after November 1, 2019 as the first case of novel coronavirus was only reported in December 2019. All titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers against a set of pre-defined eligibility criteria. Potentially eligible studies were selected for full-text analysis. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or appeal to a third senior reviewer (BEY). Agreement among the reviewers on study inclusion was evaluated using Cohen's kappa.8

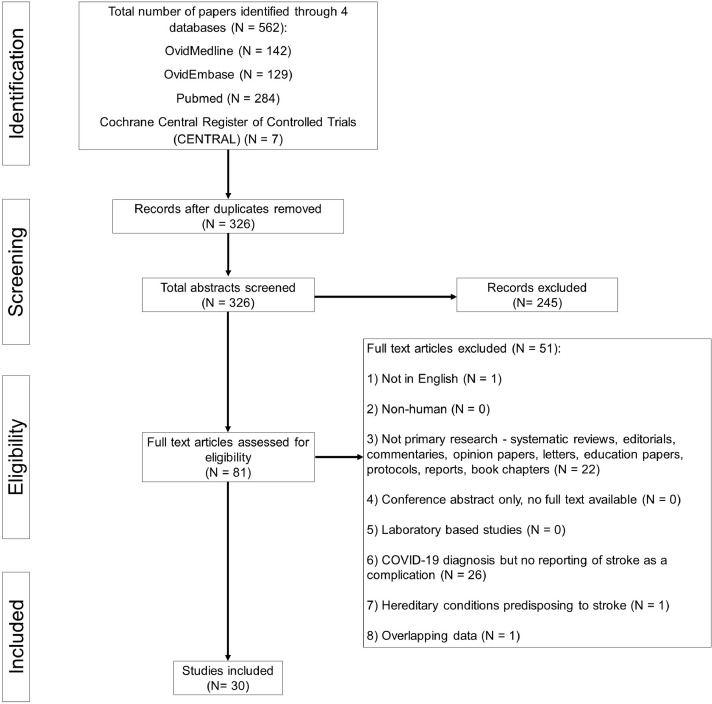

All original studies reporting the clinical characteristics (symptoms and signs, laboratory investigations and radiological findings) and treatment outcomes of COVID-19 patients with stroke complications were included in our systematic review. Case reports and studies of small sample sizes (<5) were excluded per recommendations by the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and in accordance with methodologies of previously published meta-analyses.9 Other exclusion criteria included non-English articles, non-original research papers, laboratory-based and epidemiological studies with no clinical characteristics reported, as well as non-human research subjects [Supplementary Table S2]. The PRISMA chart is detailed in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Chart.

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for prevalence studies and the JBI checklist for case series.10 In summary, these tools rated the quality of selection, measurement and comparability for all studies and gave a score for cross-sectional studies and case series. Two researchers assessed the quality of all included studies and discussed discrepancies until consensus was reached. Funnel plots were generated to check the publication bias of the included studies [Supplementary figures S1 – S5].

Data was extracted on the following variables: study details, sample size of study, method of diagnosis, age, gender, coexisting medical conditions, clinical symptoms, laboratory investigations, treatment details, and patient outcomes. The primary outcome measure was mortality in hospital. Secondary outcome measures included a stay in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or High Dependency Unit (HDU) and ventilator use.

Random effects meta-analyses were performed on variables and end points due to observed estimates and sampling variability across studies. Pooled proportions were computed with the inverse variance method using the variance-stabilising Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation.11 Confidence intervals (CI) for individual studies were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson interval method. The I2 statistic was used to present between-study heterogeneity, where I2 ≤ 30%, between 30% and 50%, between 50% and 75%, and ≥ 75% were considered to indicate low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.12 P values for the I2 statistics were computed by chi-square distribution of Cochran Q test. Missing values of mean were input using median. Statistical analysis was performed using R Core Team.13 We fixed type I error at 5% (p < 0.05) and reported 95% confidence interval for all calculations.

Results

Our search strategy yielded 326 unique publications after removal of duplicates. After screening of titles and abstracts, 81 publications were reviewed in full text. A total of 30 original studies14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 were eventually included in our systematic review with a combined population of 55,176 patients, including 899 who experienced a stroke [Table 1 ]. Reliability of study selection between observers was substantial at both the title and abstract screening stage (Cohen's κ = 0.93) and the full-text review stage (Cohen's κ = 1.00).8

Table 1.

Summary of studies

| Study | Country | Study design | No. stroke patients | Age, Mean | Male, N (%) | NIHSS, Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashrafi et al. | Iran | Case series | 6 | 43.5 | 3 (50.0) | 10.2 |

| Belani et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 19 | 65.6 | ||

| Benger et al. | United States | Case series | 5 | 52.5 | 3 (60.0) | |

| Benussi et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 38 | |||

| Beyrouti et al. | United Kingdom | Case series | 6 | 69.8 | 5 (83.3) | |

| Cantador et al. | Spain | Cross-sectional | 8 | 76.4 | 7 (87.5) | |

| Coolen et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 19 | 77.0 | 14 (73.7) | |

| D'Anna et al. | United Kingdom | Case series | 8 | 64.4 | 7 (87.5) | 9.1 |

| Escalard et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 10 | 59.5* | 8 (80.0) | 22.0* |

| Immovilli et al. | Italy | Case series | 19 | 9.8 | ||

| Jain et al. | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | 35 | 66.0* | ||

| Khan et al. | United Kingdom | Case series | 22 | 46.3 | 20 (90.9) | |

| Kihira et al. | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 18 | |||

| Klok et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 5 | |||

| Kremer et al. | United States | Case series | 37 | 61.0 | 30 (81.1) | |

| Li et al. | China | Case series | 11 | 75.5 | 5 (45.5) | 14.4 |

| Lodgiani et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 9 | 68.4 | 6 (66.7) | |

| Merkler et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 31 | 69.0* | 18 (58.1) | 16.0* |

| Mohamud et al. | United States | Case series | 6 | 65.8 | 5 (83.3) | 13.3 |

| Morassi et al. | Italy | Case series | 6 | 68.5 | 5 (83.3) | |

| Nalleballe et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 406 | |||

| Oxley et al. | United States | Case series | 5 | 40.4 | 4 (80.0) | 16.8 |

| Pons-Escoda et al. | Spain | Cross-sectional | 20 | 71.0* | 13 (65.0) | |

| Scullen et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 7 | |||

| Sierra et al. | Germany | Case series | 8 | 68.5* | 7 (87.5) | 27.0* |

| Sweid et al. | United Kingdom | Case series | 22 | 59.5 | 10 (45.5) | 13.8 |

| Varatharaj et al. | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 66 | 73.5* | 44 (66.7) | |

| Wang et al. | United Kingdom | Case series | 5 | 52.8 | 4 (80.0) | 22.8 |

| Xiong et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 10 | |||

| Yaghi et al. | United States | Cross-sectional | 32 | 63.0* | 23 (71.9) | 29.0* |

| Overall | 899 | 65.5† | 241 (70.5) | 17.9† |

Data originally reported as median.

Weighted average.

The majority of the 30 studies originated from the United States (N = 15, 50.0%) and the United Kingdom (N = 7, 23.3%). Two studies each originated from Italy and Spain and 1 study each originated from China, Germany, Iran and the Netherlands [Table 1]. Sixteen studies were cross-sectional in nature (53.3%) and 14 (46.7%) were case series. Of the 16 cross-sectional studies, 6 studies attained a full score of 8 on the JBI checklist for cross-sectional studies, 1 study attained a score of 7, and 9 studies attained a score of 6 [Supplementary Table S3]. Of the 14 case series, 13 studies attained a full score of 10 on the JBI checklist for case series and 1 study attained a score of 7 [Supplementary Table S4].

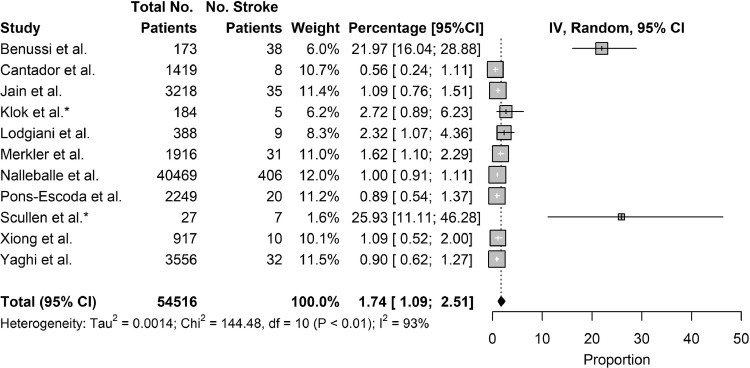

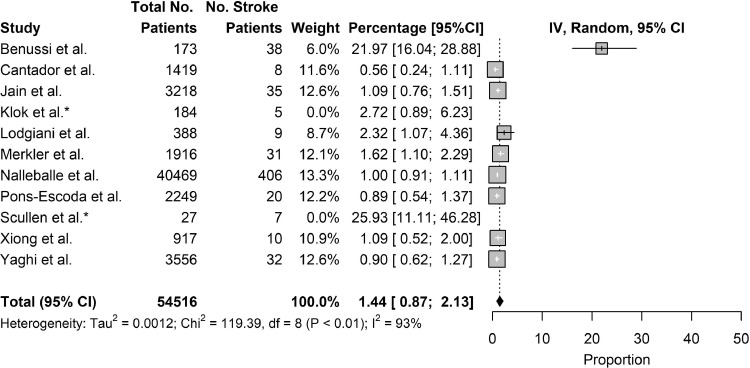

Eleven studies reported on the incidence of stroke as a complication of COVID-19, including 2 studies which reported on the incidence of stroke as a complication in critically-ill COVID-19 patients. Combining results, the pooled incidence of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 1.74% (95% CI: 1.09% to 2.51%). Excluding the 2 studies which studied critically-ill populations, the incidence of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 patients was 1.44% (95% CI: 0.87% to 2.13%). Notably, 3 of the 11 studies reported incidence under 1% [Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ].

Fig. 2.

Incidence of Stroke.

Fig. 3.

Incidence of Stroke Excluding Critically-ill Studies.

Demographic information of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was analysed. The mean age of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 65.5 years (Range: 40.4–77.0 years). More males suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 than females, with 70.5% of such patients being male. The average admission National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of patients who suffered stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 17.9 (Range: 9.1–29.0) [Table 1]. The most common comorbidities in patients were hypertension (57.5% of patients), hyperlipidaemia (40.1%), and diabetes mellitus (33.7%). Less commonly encountered comorbidities included ischaemic heart disease (26.3%), malignancy (23.1%), chronic kidney disease (16.9%), and smoking (14.2%) [Table 2 ].

Table 2.

Comorbidities

| Study | No. stroke Patients | Diabetes Mellitus, N (%) | Hypertension, N (%) | Hyperlipidaemia, N (%) | Chronic Kidney Disease, N (%) | Ischaemic heart disease, N (%) | Malignancy, N (%) | Smoking, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashrafi et al. | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Benger et al. | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | |||

| Beyrouti et al. | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||||

| Cantador et al. | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 8 (100.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (75.0) | ||

| Coolen et al. | 29 | 6 (20.7) | 16 (55.2) | 7 (24.1) | 5 (17.2) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| D'Anna et al. | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Escalard et al. | 20 | 4 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Immovilli et al. | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 16 (84.2) | |||||

| Jain et al. | 35 | 14 (40.0) | ||||||

| Khan et al. | 22 | 8 (36.4) | 7 (31.8) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | |||

| Li et al. | 11 | 6 (54.5) | 9 (81.8) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (36.4) | ||

| Lodgiani et al. | 9 | 2 (22.2) | ||||||

| Merkler et al. | 31 | 23 (74.2) | 30 (96.8) | 17 (54.8) | 8 (25.8) | 16 (51.6) | ||

| Mohamud et al. | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 1 (16.7) | ||||

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | |||

| Oxley et al. | 5 | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | ||||

| Pons-Escoda et al. | 20 | 5 (25.0) | 13 (65.0) | 9 (45.0) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Sierra et al. | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Sweid et al. | 22 | 2 (9.1) | 10 (45.5) | 1 (4.5) | 3 (13.6) | |||

| Wang et al. | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||||

| Yaghi et al. | 32 | 11 (34.4) | 18 (56.3) | 18 (56.3) | 7 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Overall | 313 | 91 (33.7) | 172 (57.5) | 69 (40.1) | 10 (16.9) | 45 (26.3) | 15 (23.1) | 21 (14.2) |

Clinical symptoms of patients such as COVID-19 symptoms and stroke symptoms were analysed. Of the 11 studies that reported on COVID-19 symptoms, 7 reported that all the patients included in their study experienced at least 1 COVID-19 symptom during their clinical course. Shortness of breath (59.1% of patients) and cough (56.2%) were the most common symptoms experienced. Fever (43.0%) and myalgia (41.7%) were less common. Additionally, 24.5% of patients were asymptomatic i.e. did not experience any COVID-19 symptoms. Of the 9 studies that reported on stroke symptoms, all reported that at least half of the patients in their study experienced one or more stroke symptoms. Common stroke symptoms included unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia (66.7%), loss of consciousness or decreased levels of consciousness (66.0%), and headache (11.9%). Other less common symptoms that patients with stroke as a complication of COVID-19 suffered from were aphasia, generalised weakness, and dizziness [Table 3 ].

Table 3.

Clinical symptoms

| Study | No. stroke patients | Stroke symptoms |

COVID-19 symptoms |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache, N (%) | Loss/decreased Consciousness, N (%) | Unilateral hemiparesis/hemiplegia, N (%) | Fever, N (%) | Cough, N (%) | Myalgia, N (%) | Shortness of breath, N (%) | Asymptomatic, N (%) | ||

| Ashrafi et al. | 6 | 6 (100.0) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Benger et al. | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 5 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | |||

| Beyrouti et al. | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | |||

| Coolen et al. | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 5 (26.3) | 10 (52.6) | 18 (94.7) | ||||

| D'Anna et al. | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 4 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | |||||

| Escalard et al. | 10 | 5 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||||

| Khan et al. | 22 | 18 (81.8) | 12 (54.5) | 6 (27.3) | |||||

| Kremer et al. | 37 | 4 (10.8) | 27 (73.0) | ||||||

| Mohamud et al. | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | |||||

| Oxley et al. | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Sweid et al. | 22 | 10 (45.5) | 11 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) | 9 (40.9) | ||||

| Overall | 152 | 8 (11.9) | 35 (66.0) | 48 (66.7) | 40 (43.0) | 59 (56.2) | 5 (41.7) | 52 (59.1) | 12 (24.5) |

Clinical parameters of COVID-19 patients who suffered from stroke as a complication were also analysed. Six studies reported results of liver function tests. Aminotransferase (AST) levels were raised, with an average of 51.9 u/L (Range: 28–116 u/L). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were mildly raised, with an average of 58.2 u/L (Range: 28–75 u/L). CRP levels were within normal range, with an average of 10.0 u/L (Range: 2.27–20.80 u/L). Fifteen studies reported on coagulation profile. D-dimer levels were raised, with an average of 3,301.1 ng/mL (Range: 3–25,261 ng/mL). Prothrombin time (PT) was raised, with an average of 13.1 s (Range: 10.0 s–15.52 s). Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was within normal range, with an average of 24.2 s (Range: 2.10 s–55.00 s). Nine studies reported on full blood count. Haemoglobin (Hb) levels were low, with an average of 10.3 g/dL (Range: 9.12–12.89 g/dL). Platelet (Plt) levels were within normal range, with an average of 240,704.3 per mm3 (Range: 78,000–319,000 per mm3). White blood cell (WBC) levels were within normal range, with an average of 10,094.8 cells/mm3 (Range: 7,193–12,400 cells/mm3) [Table 4 ].

Table 4.

Clinical parameters

| Study | No. stroke patients | Full blood counts |

Coagulation profile |

Liver function tests |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dL) | WBC (cells/mm3) | Plt (per mm3) | PT (s) | aPTT (s) | D-dimer (ng/mL) | AST (u/L) | ALT (u/L) | CRP (u/L) | Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||

| Ashrafi et al. | 6 | 12.89 | 7,193 | 195,000 | 13.33 | 34.33 | 845 | 28 | 28 | 15.00 | |

| Benger et al. | 5 | 9.12 | 12,400 | 277,000 | 2.10 | 5,572 | 72 | 11.10 | 20.88 | ||

| Beyrouti et al. | 6 | 12.17 | 8,328 | 290,000 | 15.52 | 32.50 | 25,261 | 55 | 13.90 | ||

| Cantador et al. | 8 | 3 | 10.10 | ||||||||

| D'Anna et al. | 8 | 8,438 | 319,000 | 15.44 | 55.00 | 4,053 | 10.49 | ||||

| Khan et al. | 22 | 10.00 | 3.00 | 4,400 | 7.62 | ||||||

| Kremer et al. | 37 | 9.79 | 11,800 | 292,000 | 14.00 | 2,900 | 48 | 75 | 5.85 | 1.27 | |

| Li et al. | 11 | 7,700 | 142,000 | 690 | 32 | 24 | 5.11 | 0.85 | |||

| Merkler et al. | 31 | 10,300 | 210,000 | 1,930 | |||||||

| Mohamud et al. | 6 | High | High | ||||||||

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 78,000 | 53.10 | 3,997 | 116 | 47 | 2.27 | 2.22 | |||

| Oxley et al. | 5 | 7,420 | 298,000 | 13.80 | 31.90 | 3,658 | |||||

| Sweid et al. | 22 | 35 | 20.80 | ||||||||

| Wang et al. | 5 | High | High | High | High | ||||||

| Yaghi et al. | 32 | 3,913 | 10.10 | ||||||||

| Overall | 210 | 10.3 | 10094.8 | 240704.3 | 13.1 | 24.2 | 3301.1 | 51.9 | 58.2 | 10.0 | 3.0 |

Twenty-seven studies reported the type of stroke, whether ischaemic or haemorrhagic. Ischaemic stroke included large vessel strokes and lacunar strokes. Haemorrhagic stroke included subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage. Ischaemic stroke was more common than haemorrhagic stroke as a complication of COVID-19, with an average of 82.8% of patients suffering from ischaemic stroke as a complication of COVID-19 and only 17.2% of patients suffering from haemorrhagic stroke as a complication of COVID-19 [Table 5 ].

Table 5.

Type of stroke (Ischaemic VS Haemorrhagic)

| Study | No. stroke patients | Ischaemic stroke, N (%) | Haemorrhagic stroke, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashrafi et al. | 6 | 6 (100.0) | 0 |

| Belani et al. | 19 | 19 (100.0) | 0 |

| Benger et al. | 5 | 0 (0.0) | 5 |

| Benussi et al. | 38 | 35 (92.1) | 3 |

| Beyrouti et al. | 6 | 6 (100.0) | 0 |

| Cantador et al. | 8 | 8 (100.0) | 0 |

| Coolen et al. | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 15 |

| D'Anna et al. | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 1 |

| Escalard et al. | 10 | 10 (100.0) | 0 |

| Immovilli et al. | 19 | 17 (89.5) | 2 |

| Jain et al. | 35 | 26 (74.3) | 9 |

| Khan et al. | 22 | 22 (100.0) | 0 |

| Klok et al. | 5 | 5 (100.0) | 0 |

| Kremer et al. | 37 | 17 (45.9) | 20 |

| Li et al. | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 1 |

| Lodgiani et al. | 9 | 9 (100.0) | 0 |

| Merkler et al. | 31 | 31 (100.0) | 0 |

| Mohamud et al. | 6 | 6 (100.0) | 0 |

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 2 |

| Oxley et al. | 5 | 5 (100.0) | 0 |

| Pons-Escoda et al. | 20 | 13 (65.0) | 7 |

| Scullen et al. | 7 | 4 (57.1) | 3 |

| Sierra et al. | 8 | 8 (100.0) | 0 |

| Sweid et al. | 22 | 19 (86.4) | 3 |

| Varatharaj et al. | 66 | 57 (86.4) | 9 |

| Wang et al. | 5 | 5 (100.0) | 0 |

| Yaghi et al. | 32 | 32 (100.0) | 0 |

| Overall | 465 | 385 (82.8) | 80 (17.2) |

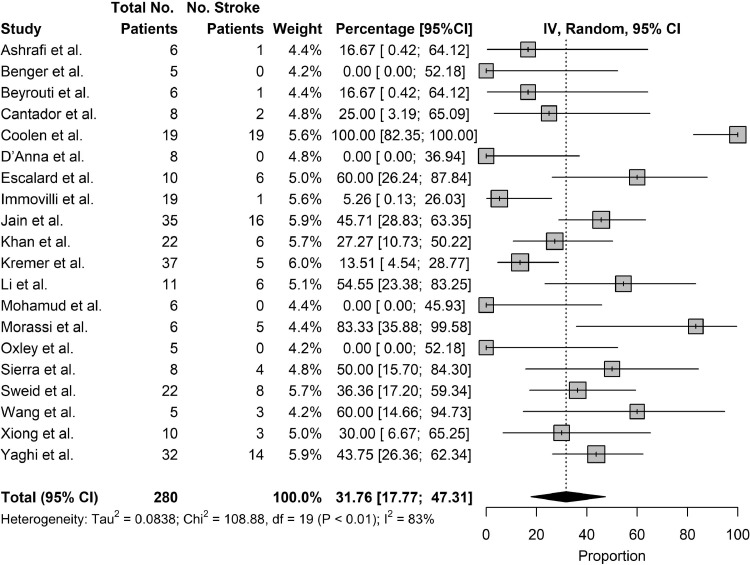

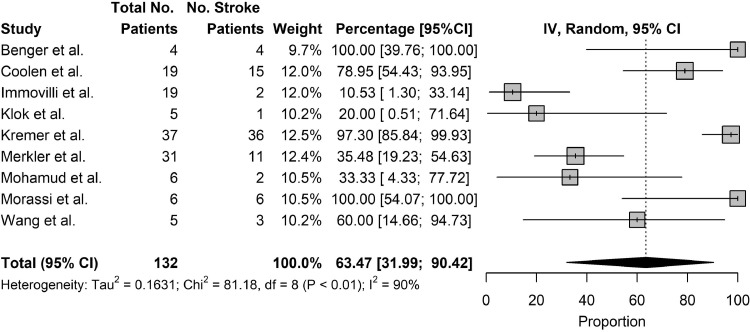

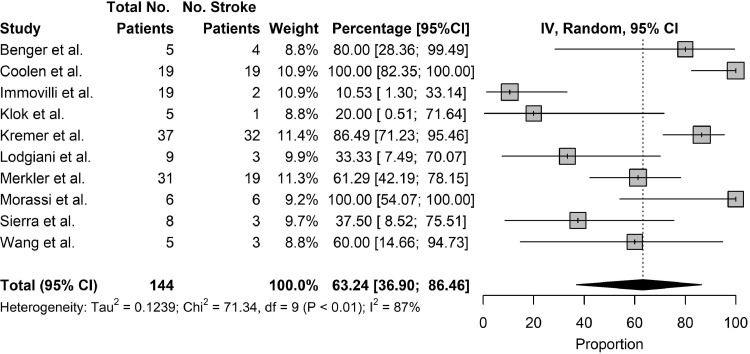

The primary outcome studied was the mortality rate of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 and the secondary outcomes studied were the rates of ventilator use and rates of ICU/HDU stay. Twenty studies reported on the mortality rate of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. The pooled mortality rate of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 31.76% (95% CI: 17.77% to 47.31%) [Fig. 4 ]. Among severely ill patients, the pooled mortality rate was 84.8% [Table 6 ]. Nine studies reported rates of ventilator use in patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. The pooled rates of ventilator use in patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 63.47% (95% CI: 31.99% to 90.42%) [Fig. 5 ]. Ten studies reported rates of ICU/HDU stay in patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. The pooled rates of ICU/HDU stay in patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was 63.24% (95% CI: 36.90% to 86.46%) [Figure 6 ].

Fig. 4.

Outcomes, Mortality.

Table 6.

Outcomes, mortality (severely ill)

| Study | No. stroke patients, N | Death, N (%) | Survival, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coolen et al. | 19 | 19 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Sierra et al. | 8 | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Overall | 33 | 28 (84.8) | 5 (15.2) |

Fig. 5.

Outcomes, Use of Ventilator.

Fig. 6.

Outcomes, ICU/HDU Stay.

In different subgroups of COVID-19 patients who suffered from stroke as a complication, the outcomes varied. Four studies with a combined population of 38 patients reported on stroke as a complication of COVID-19 in young patients, aged 60 and below. The average age was 45.9 (Range: 40.4–52.8). The average NIHSS was 16.2 (Range: 10.2–22.8). All patients studied suffered from ischaemic stroke, and none suffered from haemorrhagic stroke. The outcomes were better than that of the general population of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19, with 73.7% of patients surviving and 26.3% of patients suffering mortality. Four studies with combined population of 260 patients reported on stroke as a complication of COVID-19 in severely-ill patients. Severe illness was categorised either by author's definition or defined as patients who required admission to the ICU or HDU. The incidence of stroke in severely-ill patients COVID-19 patients was 9.8% (Range: 2.7% to 30.6%). The average age was 73.4 (Range: 68.5–77.0). The proportion of patients who suffered from ischaemic stroke and haemorrhagic stroke were similar, with 55.3% suffering from ischaemic stroke and 44.7% of patients suffering from haemorrhagic stroke. The outcomes were poor, with 84.8% of patients suffering mortality and 15.2% of patients surviving. Four studies with a combined population of 3,403 patients reported on stroke as a complication of COVID-19 in patients with comorbidities. Comorbidities studied included hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, ischaemic heart disease, malignancy and smoking. The incidence of stroke in COVID-19 patients with comorbidities was 1.2% (Range: <1%–1.6%). The majority of patients suffered from ischaemic stroke, with 76.6% suffering from ischaemic stroke and 23.4% suffering from haemorrhagic stroke. The outcomes were poor, with 63.6% of patients suffering mortality and 36.4% of patients surviving [Table 7 ].

Table 7.

Analysis of patient subgroups

| First author | No. patients | No. stroke patients | Age, Mean | NIHSS, Mean | Incidence of stroke (%) | Type of stroke |

Outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic, N (%) | Haemorrhagic, N (%) | Death, N (%) | Survival, N (%) | ||||||

| Young Patients Subgroup | |||||||||

| Ashrafi et al. | 6 | 43.5 | 10.2 | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||

| Khan et al. | 22 | 46.3 | 22 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | |||

| Oxley et al. | 5 | 40.4 | 16.8 | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Wang et al. | 5 | 52.8 | 22.8 | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Overall | 38 | 45.9 | 16.2 | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (73.7) | ||

| Severely-ill Patients Subgroup | |||||||||

| Coolen et al. | 62 | 19 | 77.0 | 30.6 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 19 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Klok et al. | 184 | 5 | 2.7 | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Morassi et al. | 6 | 6 | 68.5 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Sierra et al. | 8 | 8 | 68.5 | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | ||

| Overall | 260 | 38 | 73.4 | 9.8 | 21 (55.3) | 17 (44.7) | 28 (84.8) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Patients with Comorbidities Subgroup | |||||||||

| Cantador et al. | 1,419 | 8 | 76.4 | <1.0 | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | |

| Coolen et al. | 62 | 19 | 77.0 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 19 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Merkler et al. | 1,916 | 31 | 69.0 | 16.0 | 1.6 | 31 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Mohamud et al. | 6 | 6 | 65.8 | 13.3 | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (100.0) | |

| Overall | 3403 | 64 | 72.0 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4) | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) |

Discussion

We comprehensively evaluated the epidemiology, incidence, clinical course, and outcomes of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. Our study shows that the incidence of stroke in COVID-19 patients is relatively low, but increases in certain subgroups such as the severely-ill. However, patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 have poor outcomes including admission to intensive care facilities, use of ventilators, and high mortality rate. In certain subgroups, such as the severely-ill and those with comorbidities, the mortality rate is even higher. It might be helpful to be vigilant of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 as, although uncommon, it can have severe consequences to patient outcomes.3

Demographic risk factors such as age and comorbidities were found to increase risk of suffering from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. Firstly, patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 are generally older, with an average age of 65.5 years (Range: 40.4–76.4 years). However, some studies have reported on the phenomenon of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 in young patients,14 , 25 , 35 , 41 which will be further discussed in a subsequent section. Secondly, most patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 have one or more pre-existing comorbidities. The most common comorbidities reported are hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Although less common, malignancy is also a comorbidity reported in some patients, possibly because it increases coagulopathy.44 Although the reason for stroke being a more common complication in elderly COVID-19 patients with pre-existing medical conditions is still unclear, one theory is that their lower levels of physiological reserves results in insufficient reserves to compensate for the physiological derangements caused by COVID-19.45 Interestingly, a significant number of studies report a male preponderance for stroke complications in covid-19 patients. This aetiology is still unknown.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 include mild symptoms such as cough and fever, as well as more severe symptoms such as shortness of breath.14 , 16 , 18 Common symptoms of stroke include hemiparesis or hemiplegia and headache.28 , 32 , 35 Most often, patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 experience both COVID-19 symptoms and stroke symptoms during their clinical course. However, some patients who suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 experience only stroke symptoms and are asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19.22 , 25 , 32 , 35 One theory is that it could be due to the differences in severity of disease with more severe disease manifesting in symptoms while less severe disease being asymptomatic.46 Another theory relates to the patient's individual physiological reserves where patients with higher reserves can withstand the same disease burden without experiencing symptoms.45 This phenomenon has implications on clinical practice. If clinicians encounter patients with only stroke symptoms and no COVID-19 symptoms, it is still important for them to be conscious that these patients may be asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19.22 , 25 , 32 , 35 Exercising an appropriate level of caution when treating such patients could be beneficial especially if they have risk factors for COVID-19, such as positive contact or travel histories.47 Several reviews have proposed comprehensive stroke activation plans in the COVID-19 climate to maximise clinician safety while not compromising on patient care and patient outcomes.47

As compared to the general population of COVID-19 patients, young patients are less likely to suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. Additionally, young COVID-19 patients who suffer from stroke also tend to have better outcomes, as observed by their lower levels of mortality and lower rates of admission to the ICU or HDU for care. In contrast, severely-ill patients and those with comorbidities are more likely to suffer from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 as compared to the general population of COVID-19 patients. These two subgroups also tend to have worse outcomes.20 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 38 It remains unclear whether stroke is a direct complication of severe COVID-19, or whether it is the consequence of stress in vulnerable populations with less physiological reserves. Summarily, we conclude that older patients, patients with comorbidities, and severely ill patients have a higher likelihood of suffering from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 and also have poorer outcomes. Therefore, these subgroups would benefit from closer monitoring for the occurrence of stroke.

Ischaemic stroke is more a common complication of COVID-19 compared to haemorrhagic stroke.14 , 15 , 17 Out of the ischaemic strokes, more patients seem to suffer from large vessel strokes compared to small vessel or lacunar strokes.22 , 31 , 38 However, as few studies reported on the stroke subtypes (whether large vessel or small vessel), this review is unable to come to definitive conclusion in this area. Notably, there are also a few reports of haemorrhagic stroke as a complication of COVID-19.20 , 24 , 28 Patients with haemorrhagic stroke tend to fare worse than those with ischaemic stroke. Some proposed mechanisms of the pathophysiology of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 are as follows.

Firstly, systemic processes could give rise to stroke as a complication of COVID-19. Such systemic processes include increased coagulopathy48 and inflammatory response.49 Regarding coagulopathy, the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) is mediated by COVID-19 virus or viral products.49 This causes the development of severe coagulopathy, defined as COVID-19 associated coagulopathy (CAC). CAC is characterised by elevation of blood coagulation markers (D-dimers, fibrinogen), rise of peripheral inflammatory markers (PT, aPTT), and mild thrombocytopenia, and leads to increased clot formation. Among other places, clots also embolise to cerebral arteries, leading to an increase in rates of ischaemic stroke. Regarding inflammatory response, in some case reports of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19, antiphospholipid antibodies were present in high levels.50 Such antiphospholipid antibodies include anticardiolipin IgA antibodies as well as anti–β2-glycoprotein I IgA and IgG antibodies. Antiphospholipid antibodies launch an inappropriate autoimmune response against the body's phospholipid proteins, and their presence in high levels indicates the possibility of antiphospholipid syndrome. This autoimmune response may play a role in mediating stroke as a complication of COVID-19.48 As there is anecdotal evidence from several case reports illustrating this phenomenon, future work could explore this systematically to provide a better understanding.

Secondly, direct invasion of the brain parenchyma by SARS-CoV-2 could also give rise to stroke as a complication of COVID-19.49 SARS-CoV-2 can bind to ACE-II receptors of host cells. ACE-II receptors are expressed in a variety of tissue types, including the epithelial cells of the respiratory system, the endothelial cells of the gastrointestinal system, as well as our area of interest, neurons and glial cells of the central nervous system (CNS). SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE-II receptors in cells of the CNS and enters via receptor-mediated endocytosis, depleting the ACE-II receptors in the process. This leaves the ACE-I receptor unopposed, causing increased generation of angiotensin II, leading to downstream effects of neuroinflammation and vasoconstriction, ultimately resulting in stroke. Notably however, the level of ACE-II receptors in the CNS is low, making this mechanism more likely a supportive cause rather than a primary cause of stroke as a complication of COVID-19. The pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 bears resemblance to that seen in previous coronavirus outbreaks such as SARS-CoV from 2002–2004 and, to a lesser extent, MERS in 2012, where the aforementioned coronaviruses caused strokes via induction of a hypercoagulable state or direct invasion into the brain parenchyma.3

Of late, there has been some discussion regarding the extent to which serological testing of COVID-19 in patients with stroke could be employed. Although screening all stroke patients for COVID-19 would be ideal47 given the high morbidity of stroke and the fact that a positive COVID-19 status would alter course of treatment, the low incidence of stroke as a complication of COVID-1924,34,43 makes it challenging to justify the amount of resources required for such screening. Perhaps screening could be justified in certain subgroups of patients such as those with comorbidities, for whom the outcomes are poorer20 , 31 and would thus require more watchful care if a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 is made.

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, many of the studies included were case series, which held prominent publication bias. Secondly, only studies published in English were included which may introduce selection bias. Unpublished materials (such as recently completed studies) were also excluded, which might affect the conclusions drawn. Future work could explore the incidence of stroke with a greater sample size to gain a more accurate picture. Further investigations of the phenomenon of stroke as a complication of COVID-19 in young patients with no comorbidities and in asymptomatic COVID-19 patients would also help to expand our observations.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19. Although the incidence of stroke in hospitalized COVID-19 patients was low at 1.74%, the mortality rate of patients who suffered from stroke as a complication of COVID-19 was high at 31.76%. In COVID-19 patients, stroke was associated with older age, comorbidities, and severe illness. Further research through collaborative international registries would help us to comprehensively decipher the pathophysiology and prognosis of stroke in COVID-19, improving the effectiveness of care.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are entirely our own and not an official position of our institutions.

Ethics approval statements that refer to your institution

Research ethics approval was not applicable as this submission did not involve human participants. All information was obtained from publicly available, published manuscripts.

Contributorship statement

I.S. conceived of the presented ideas, conducted data extraction, and wrote the manuscript with support from K.S.L. and J.Z. S.E.S. designed the computational framework and performed the analytic calculations. A.N. and B.E.Y. supervised the project.

Funding

There are no funders to report for this submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No, there are no competing interests for any author.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Toh Kim Kee for her assistance in designing the initial search strategy.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105549.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.McKibbin W, Fernando R. The economic impact of COVID-19. Econ Time COVID-19. 2020:45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montalvan V, Lee J, Bueso T, De Toledo J, Rivas K. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. In.Vol 194. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery: Elsevier B.V.; 2020:105921–105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Trejo-Gabriel-Galan JM. Stroke as a complication and prognostic factor of COVID-19. Neurologia. 2020;35(5):318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy ST, Garg T, Shah C, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19: a review of the literature and case series. Case Rep Neurol. 2020;12(2):199–209. doi: 10.1159/000508958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan YK, Goh C, Leow AST, et al. COVID-19 and ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-summary of the literature. J Thromb Thromb. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02228-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Ornello R, Sacco S. Ischemic stroke epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic: navigating uncharted waters with changing tides. Stroke. 2020;51(7):1924–1926. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang JJY, Ong JA, Syn NL, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pregnant and postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0885066619892826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J EvidBased Med. 2015;8(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1. 0 [updated March 2011] Cochrane Collab. 2011 Available from www. cochrane-handbook. org. Accessed August. 2011;29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Core Team R. Available. 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R foundation for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashrafi F, Zali A, Ommi D, et al. COVID-19-related strokes in adults below 55 years of age: a case series. Neurol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belani P, Schefflein J, Kihira S, et al. COVID-19 is an independent risk factor for acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benger M, Williams O, Siddiqui J, Sztriha L. Intracerebral haemorrhage and COVID-19: clinical characteristics from a case series. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benussi A, Pilotto A, Premi E, et al. Neurology; Lombardy, Italy: 2020. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of inpatients with neurologic disease and COVID-19 in Brescia. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009848-00000000000098 10.0000000000001212/WNL.0000000000009848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, et al. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. BMJ Publishing Group; 2020. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantador E, Núñez A, Sobrino P, et al. Incidence and consequences of systemic arterial thrombotic events in COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020:1. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coolen T, Lolli V, Sadeghi N, et al. Early postmortem brain MRI findings in COVID-19 non-survivors. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010116. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010116-00000000000 10110.0000000000011212/WNL.0000000000010116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Anna L, Kwan J, Brown Z, et al. Characteristics and clinical course of Covid-19 patients admitted with acute stroke. In. Vol 1. J Neurol: Springer; 2020:3–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Escalard S, Maïer B, Redjem H, et al. Stroke. 2020. Treatment of acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion with COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Immovilli P, Terracciano C, Zaino D, et al. Stroke in COVID-19 patients—a case series from Italy. Int J Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1747493020938294. 174749302093829-174749302093829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain R, Young M, Dogra S, et al. COVID-19 related neuroimaging findings: a signal of thromboembolic complications and a strong prognostic marker of poor patient outcome. J Neurol Sci. 2020;414 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116923. 116923-116923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan M, Ibrahim RHM, Siddiqi SA, et al. SAGE Publications Inc.; 2020. COVID-19 and acute ischemic stroke – A case series from Dubai, UAE. 174749302093828-174749302093828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kihira S, Schefflein J, Chung M, et al. Incidental COVID-19 related lung apical findings on stroke CTA during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neuro Interv Surg. 2020;12(7):669–672. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: An updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kremer S, Lersy F, de Sèze J, et al. Brain MRI findings in severe COVID-19: a retrospective observational study. Radiology. 2020:202222. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Li M, Wang M, et al. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000431. 0:svn-2020-000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamud AY, Griffith B, Rehman M, et al. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020. Intraluminal Carotid Artery Thrombus in COVID-19: another danger of cytokine storm? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morassi M, Bagatto D, Cobelli M, et al. Stroke in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: case series. J Neurol. 2020;1:1. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09885-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nalleballe K, Reddy Onteddu S, Sharma R, et al. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations in COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. e60–e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pons-Escoda A, Naval-Baudín P, Majós C, et al. Neurologic involvement in COVID-19: cause or coincidence? a neuroimaging perspective. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scullen T, Keen J, Mathkour M, Dumont AS, Kahn L. Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)–associated encephalopathies and cerebrovascular disease: the new orleans experience. World Neurosurg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sierra-Hidalgo F, Muñoz-Rivas N, Torres Rubio P, et al. Large artery ischemic stroke in severe COVID-19. In. J Neurol: Springer; 2020:1 -1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Sweid A, Hammoud B, Bekelis K, et al. Cerebral ischemic and hemorrhagic complications of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1747493020937189. 174749302093718-174749302093718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X. 0(0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang A, Mandigo GK, Yim PD, Meyers PM, Lavine SD. Stroke and mechanical thrombectomy in patients with COVID-19: Technical observations and patient characteristics. J NeuroInterv Surg. 2020;12(7):648–653. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong W, Mu J, Guo J, et al. Neurology; 2020. New onset neurologic events in people with COVID-19 infection in three regions in China. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and Stroke in a New York healthcare system. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2002–2011. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchiyama T, Matsumoto M, Kobayashi N. Studies on the pathogenesis of coagulopathy in patients with arterial thromboembolism and malignancy. Thromb Res. 1990;59(6):955–965. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90119-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esme M, Topeli A, Yavuz BB, Akova M. Infections in the Elderly Critically-Ill Patients. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:118. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Yan LM, Wan L, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, Chapman MG, Menon BK. Protected code stroke: hyperacute stroke management during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51(6):1891–1895. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Divani AA, Andalib S, Di Napoli M, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Stroke: Clinical Manifestations and Pathophysiological Insights. In. Vol 29: W.B. Saunders; 2020:104941-104941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Hess DC, Eldahshan W, Rutkowski E. COVID-19-Related Stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11(3):322–325. doi: 10.1007/s12975-020-00818-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.