Dear editor,

We have with interest read the paper by Garrigues et al.1, showing that symptoms may persist several months after hospitalization for COVID-19, as also shown elsewhere.2 Garrigues et al. also showed that there was little difference in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) between ward and ICU patients.1 There is less evidence for the non-hospitalised, but breathlessness and fatigue is common after several months.3 , 4

The majority of those diagnosed with COVID-19 are not hospitalised, and yet there is little evidence relating to their HRQoL, though a recent study reported on quality of life in non-hospitalised subjects recruited from a Facebook support group for patients with persistent complaints after confirmed/suspected COVID-19.5

The present study assessed HRQoL with the widely used EQ-5D and RAND-36 instruments in a population-based cohort of non-hospitalised subjects in Norway, on average 4 months after their COVID-19. Scores were compared with general population norms.

This was a cross-sectional survey of a geographical cohort in the catchment areas of Akershus University (Ahus) and Østfold Hospitals, covering about 900,000 inhabitants in 2020, or 17% of the population of Norway.4 Prior to 1 June 2020, 1029 PCR SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects ≥18 years were identified, of whom, 938 were eligible for the survey (Supplement, Fig.1).

At the end of June 2020, subjects received a postal invitation asking them to sign a consent form on-line via their personal identification number and national electronic identification system, and thereafter received an online web-questionnaire. Alternatively, they could complete and return paper versions. Non-respondents received a postal reminder after 5 weeks.

The questionnaire included the EQ-5D-5 L and RAND-36 (SF-36), and the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale,6 other health-related information and background characteristics. The EQ-5D-5 L assesses five items or dimensions of health — mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression — with five response levels from no problems to extreme problems/unable to do. Responses to all five dimensions represent a health state with a value attached, an index score, anchored at 0=dead and 1=full health, with values <0 indicating states worse than dead. Scoring was based on the UK EQ-5D-3 L algorithm together with a mapping algorithm (7). The RAND-36 assesses eight dimensions of health with two to five levels. Items sum to give eight scores from 0 to 100 (best health possible).8

The distributions of crude EQ-5D dimension scores were compared with Norwegian general population norms9 using Fisher's exact test. Respondents’ EQ-5D index scores and RAND-36 scores were compared with general population norms9 , 10 after matching in age- and sex- specific strata. Z-scores were used, representing the difference from the mean of the norm population reported in number of SDs. We used the paired t-test to test for statistical significance, using a 5% significance level. We also present the percentages scoring below the 5th percentile of the norms (z<−1.645). The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Health Region South East (approval no. 2020/ 149,384) and the Data Protection Officer at Akershus University Hospital approved the study.

The questionnaire was completed by 458 (49%) subjects at a median of 117.5 days after COVID-19 onset. Their mean age was 49.5 (SD 15.3) and 256 (56%) were women (Supplement, Table 1 ). In total, 289 (65%) reported no dyspnoea, 110 (25%) grade 1 and 48 (11%) grade 2–4.

Table 1.

EQ-5D-5 L and RAND-36 scores and z-scores for comparison with Norwegian general population norms* (N = 458).

| Scale score |

Z-score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | n | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P⁎⁎ | <5th percentile, n (%)⁎⁎⁎⁎ | |

| EQ-5D index ⁎⁎⁎ | 456 | 0.82 (0.17) | −0.07 (1.00) | 0.13 | 26 (6) | |

| RAND-36 (range 0 to100) | ||||||

| Physical functioning | 457 | 86.1 (18.2) | −0.04 (1.10) | 0.39 | 42 (9) | |

| Role limitations-physical | 457 | 70.5 (40.1) | −0.17 (1.16) | 0.002 | 73 (16) | |

| Bodily pain | 458 | 75.6 (24.2) | −0.01 (0.96) | 0.79 | 34 (7) | |

| General health | 451 | 65.6 (19.3) | −0.35 (0.95) | <0.001 | 49 (11) | |

| Energy/fatigue | 458 | 56.8 (23.9) | −0.20 (1.14) | <0.001 | 58 (13) | |

| Social functioning | 458 | 79.6 (23.9) | −0.32 (1.17) | <0.001 | 65 (14) | |

| Role limitations-emotional | 457 | 80.2 (35.2) | −0.15 (1.18) | 0.008 | 68 (15) | |

| Emotional well-being | 458 | 78.2 817.6) | −0.16 (1.13) | 0.003 | 49 (11) | |

adjusted for age and sex.

z-score=0.

range −0.654 to 1.00.

lower score than the 5th percentile in the norm population (z<−0.1645).

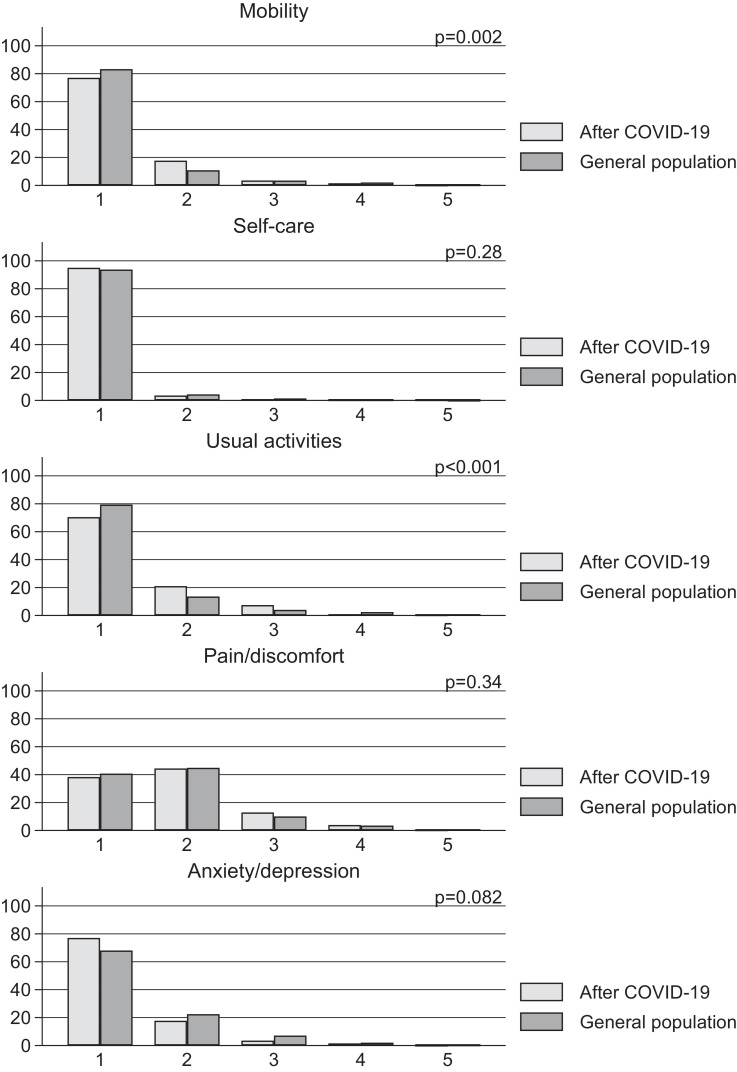

Similar response distributions to the general population were found for the five EQ-5D dimensions (Fig. 1 ). However, COVID-19 subjects had higher proportion responses to the level 2, indicative of slight problems, for mobility and usual activities dimensions. For these two dimensions, the distribution of scores differed from the general population norms.

Fig. 1.

EQ-5D dimension scores 1.5–6 months after start of COVID-19 and for Norwegian general population norms. P-values are for comparison of the distributions using Fisher's exact test.

EQ-5D index scores were not different from those for the general population (Table 1). The mean z-scores for the eight dimensions of the RAND-36 were negative, indicating poorer health, for the COVID-19 subjects. The largest mean z-scores, were found for general health followed by social functioning and energy/fatigue. Compared to general population norms, differences (p<0.01) were found for 6 of 8 RAND-36 dimension scores, the exceptions being physical functioning and pain (Table 1).

This is one of the first studies to assess HRQoL in non-hospitalised COVID-19 subjects at follow-up, using the two most widely used patient-reported outcome measures, EQ-5D and RAND-36. Lower scores than the norm population were found across important aspects of health 1.5 to 6 months following COVID-19 symptom onset. Participants had lower mobility scores on the EQ-5D, corresponding to the finding of a high proportion of subjects with persistent dyspnoea on the mMRC scale.

The mean EQ-5D index of 0.82 was similar to that reported for hospitalised patients on average 111 days after admission,1 however >1 SD higher than the 0.62 reported for Facebook-recruited subjects.5

There is some evidence for prolonged fatigue for non-hospitalised patients in the months after being diagnosed with COVID-19.3 The current study not only shows that other aspects of health are also affected in these subjects, but compared to the general population, social functioning and general health were the most affected, as shown by z-scores. Moreover, differences from RAND-36 population norms were most apparent for dimensions associated with aspects of mental health, which in addition to social functioning, included role-limitations due to emotional problems and emotional well-being.

This population-based study had a response rate of 49%, with low response in three districts having a high proportion of immigrants. Moreover, the responses were somewhat biased towards females and subjects >50 years of age, which is common in epidemiological surveys.

There is accumulating evidence that COVID-19 has a long-term impact on both hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients, which includes not just symptoms, but a broader impact on aspects of quality of life including mental health. The longer-term follow-up of both groups is recommended, and the use of widely used instruments such as the EQ-5D and RAND-36, will help understand how their health is affected over time compared to the general population.

In conclusion, in this study of non-hospitalised subjects, EQ-5D index scores did not differ from the general population norms. However, several important dimensions of HRQoL, including aspects of mental health, were lower than general population norms 1.5–6 months after COVID-19 onset.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to this work and have reviewed and approved the final version. Concept and design: all authors. Acquisition of data: KS, GE, WG. Statistical analysis: KS. Interpretation of data: KS, AMG. Writing original draft: AMG, KS. Writing review and editing: all authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors declared any competing interest relative to the present study

Financial Support

None

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Garrigues E., Janvier P., Kherabi Y., Le Bot A., Hamon A., Gouze H., et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e4–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandal S., Barnett J., Brill S.E., Brown J.S., Denneny E.K., Hare S.S., et al. Long-COVID': a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2020 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goertz Y.M.J., Van Herck M., Delbressine J.M., Vaes A.W., Meys R., Machado F.V.C., et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00542–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stavem K., Ghanima W., Olsen M.K., Gilboe H.M., Einvik G. Persistent symptoms 1.5-6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study. Thorax. 2020 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meys R., Delbressine J.M., Goertz Y.M.J., Vaes A.W., Machado F.V.C., Van Herck M., et al. Generic and respiratory-specific quality of life in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12) doi: 10.3390/jcm9123993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahler D.A., Wells C.K. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest. 1988;93(3):580–586. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hout B., Janssen M.F., Feng Y.S., Kohlmann T., Busschbach J., Golicki D., et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays R.D., Sherbourne C.D., Mazel R.M. The RAND 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2(3):217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garratt A.M., Hansen T.M., Augestad L.A., Rand K., Stavem K. Norwegian population norms for the EQ-5D-5L: results from a general population survey (Submitted). 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Garratt A.M., Stavem K. Measurement properties and normative data for the Norwegian SF-36: results from a general population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0625-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.