Abstract

Identifying the first infected case (patient zero) is key in tracing the origin of a virus; however, doing so is extremely challenging. Patient zero for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is likely to be permanently unknown. Here, we propose a new viral transmission route by focusing on the environmental media containing viruses of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or RaTG3-related bat-borne coronavirus (Bat-CoV), which we term the “environmental quasi-host.” We reason that the environmental quasi-host is likely to be a key node in helping recognize the origin of SARS-CoV-2; thus, SARS-CoV-2 might be transmitted along the route of natural host–environmental media–human. Reflecting upon viral outbreaks in the history of humanity, we realize that many epidemic events are caused by direct contact between humans and environmental media containing infectious viruses. Indeed, contacts between humans and environmental quasi-hosts are greatly increasing as the space of human activity incrementally overlaps with animals’ living spaces, due to the rapid development and population growth of human society. Moreover, viruses can survive for a long time in environmental media. Therefore, we propose a new potential mechanism to trace the origin of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Keywords: Environmental quasi-host, Patient zero, SARS-CoV-2, Pathway, Origin of COVID-19

1. Introduction

In general, identifying the first infected case (patient zero) is key in tracing the origin of a virus; however, doing so is extremely challenging. Despite extensive efforts, scientists have not yet identified patient zero for the 1918 influenza pandemic, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or H1N1 influenza in 2009, and patient zero for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is likely to remain unidentified as well. The challenge in identifying the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is that a great deal of interdisciplinary research is required; in particular, if patient zero was asymptomatic or had very mild symptoms, he or she may not have seen a doctor or generated a medical record. As a result, patient zero could forever remain unidentified. Therefore, what roadmap could be followed to skip over patient zero while still recognizing the origin of the virus?

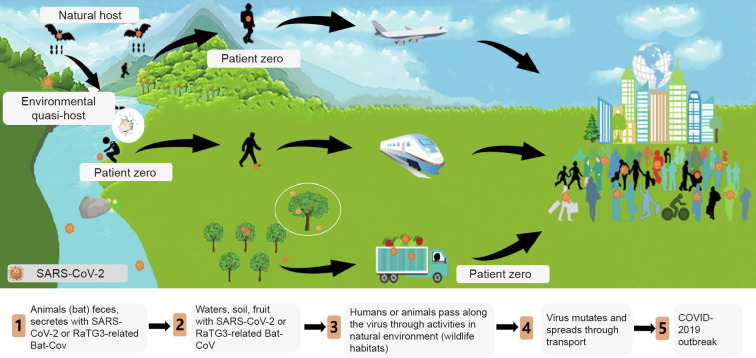

Here, we propose a new virus transmission route (Fig. 1 ) by focusing on environmental media containing viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 or RaTG3-related bat-borne coronavirus (Bat-CoV), hereafter termed as the “environmental quasi-host.” We propose reasons why the environmental quasi-host is likely to be a key node in helping recognize the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 1.

The SARS-CoV-2 transmission pathway.

Viral transmission to humans occurs via natural host–human contact or environmental quasi-host–human contact, where the environmental quasi-host might be water, soil, or food contaminated by an animal host’s urine, saliva, feces, or secretions. Many researchers believe that SARS-CoV-2 may have come from the wild animal market. Nevertheless, they have focused on the natural host–human pathway [1], [2], [3], while ignoring the natural host–environmental quasi-host–human pathway.

Is it possible that SARS-CoV-2 infected patient zero through contact with an environmental quasi-host? With rapid industrialization and globalization, contacts between humans and environmental quasi-hosts are greatly increasing, as human activity spaces strongly overlap with animals’ living spaces. Moreover, viruses can survive for a long time in certain environmental media [4], [5], [6]. Many viral outbreaks in humans have been caused by direct human contact with environmental media containing a virus, such as virus-carrying water and soil, rather than by direct contact with a natural host [7], [8], [9], [10].

Based on the following pieces of evidence from recent research and other viral transmission pathways, we consider that SARS-CoV-2 could have been transmitted from an environmental quasi-host.

2. SARS-CoV-2 detection in various environmental media

SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in various environmental media (Table 1 [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]), including wastewater, soil, floor surfaces, door handles, sinks, lockers, tables, windows, and packages, to name just a few. Between February and March of 2020, Liu and colleagues [11] at Wuhan University in China demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the air by setting up aerosol capture devices in and around two hospitals. Ong’s group [12] detected SARS-CoV-2 on environmental surfaces in patients’ rooms and toilets. SARS-CoV-2 has also been detected in wastewater at Schiphol Airport in Tilburg, the Netherlands [13]. SARS-CoV-2 may exist in the habitats of species that are natural hosts for SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, further examination of environmental media in natural habitats for SARS-CoV-2 is needed.

Table 1.

SARS-CoV-2 detected in environmental media [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

| Environmental media | Collection period | Site or country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerosol | 2020-02–2020-03 | Wuhan, China | [11] |

| Wastewater | 2019-11-27 | Florianopolis, capital of Santa Catarina in southern Brazil | [14] |

| Wastewater | 2019-12-18 | Milan and Turin, Italy | [15] |

| Wastewater | 2020-03-05–2020-04-23 | Paris, France | [16] |

| Non-potable water | 2020-04 | Paris, France | [17] |

| Floor surfaces, door handles, sinks, lockers, tables, and windows | 2020-01-24–2020-02-04 | Singapore | [12] |

| Packages and the inner wall of a container of frozen shrimp | 2020-07-03 | Beijing, China | [18] |

| Samples from seafood, meat, and the external environment | 2020-06 | Beijing, China | [19] |

| Human feces | 2020-01-01–2020-02-17 | China | [20] |

| Human feces | 2020 | China | [21] |

| Wastewater | 2020-02 | Schiphol Airport in Tilburg, the Netherland | [13] |

| Soil and wastewater | 2020-04 | Wuhan, China | [22] |

3. Long-term virus survival in environmental media

Viruses can survive in environmental media for hundreds or even thousands of days and remain infectious under suitable conditions, which are often reported to be low temperatures, relatively closed conditions, less disturbed conditions, and highly heterogeneous environmental media. Mollivirus sibericum, which has been preserved in permafrost for 30 000 years, is still capable of infection after resuscitation [23]. Porcine parvovirus can survive in soil for more than 43 weeks [6], and poliovirus remains stable and active at 1 °C for 75 days [24]. In groundwater, human norovirus still has 10% activity after 1266 days [25]. In mineral water, hepatitis A virus and poliovirus only have a small reduction in infectivity for one year at 4 °C [4]. In contaminated water, norovirus can still be detected after 1343 days [5].

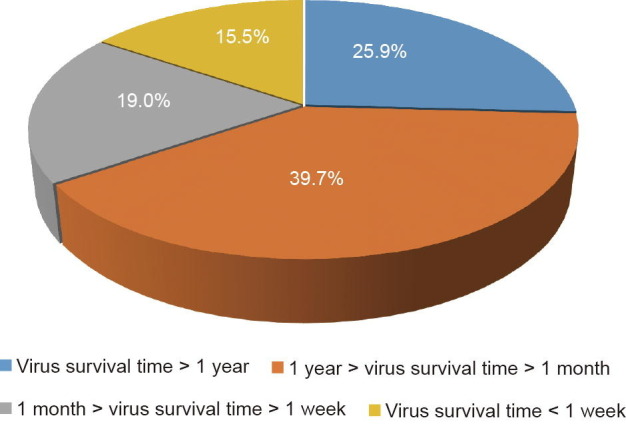

We have analyzed 482 scholarly papers published in the past 120 years (Table 2 [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122]), which study the survival time of 116 different strains of viruses. From a statistical perspective, over 84% of the 116 different strains of viruses can survive for more than one week (Fig. 2 [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122]). With the rapid development of global transportation, viruses in environmental media can be carried from one place in the world to another in days or weeks; thus, the origin of a virus could be far away from the location of its breakout. As the phylogenetic characteristics of a virus may greatly affect its survival time in environment media, the phylogenetic characteristics of viruses require further study.

Table 2.

Virus survival times in environmental media [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122].

| Virus survival time (t) | Viruses |

|---|---|

| t > 1 year | Reovirus [26], human adenoviruses [5], viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) [33], feline calicivirus (FCV) [36], calf rotavirus [26], poliovirus [4], hepatitis A virus (HAV) [4], tomato mosaic virus (TMV) [48], scrapie virus [52], H5N1 [56], H5N2 [60], H7N3 [60], H1N1 [65], H6N2 [69], H7N1 [71], marek’s disease virus (MDV) [74], mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) [75], norwalk virus [5], granulosis virus [84], avian paramyxovirus-1 (APMV-1) [87], grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) [89], tomato ringspot virus (TmRSV) [92], human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) [95], nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV) [96], African swine fever virus (ASFV) [98], swine vesicular disease virus (SVDV) [100], baculovirus midgut gland necrosis virus (BMNV) [102], granulosis viruses [Baculoviridae] [104], infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) [106], Mollivirus sibericum[23] |

| 1 year > t > 1 month | Astrovirus (AstVs) [27], pike fry rhabdovirus (PFR) [30], spring viraemia of carp virus (SVCV) [30], infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) [30], rotavirus [39], echovirus [42], Tulane virus (TV) [45], coxsackie virus [49], murine norovirus (MNV) [53], Ebola virus [57], H12N5 [61], H10N7 [61], H3N8 [66], H4N6 [66], H9N2 [72], transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) [75], hand foot mouth virus (FMDV) [78], koi herpesvirus (KHV) [81], snow mountain virus (SMV) [85], the minute virus of mice (MVM) [35], beet necrotic yellow vein virus (BNYVV) [90], salmonid alphavirus (SAV) [93], feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) [95], variola virus [97], rhesus rotavirus (RRV) [99], frog virus 3 (FV3) [101], porcine teschovirus (PTV) [103], white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) [105], lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV) [107], neurovaccine virus [108], potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd) [62], prion [109], turkey reovirus (TRVs) [110], bovine parvovirus [111], bovine enterovirus [112], hepatitis E virus (HEV) [113], channel catfish virus (CCV) [114], avian reovirus [115], infectious salmon anemia virus (ISAV) [116], infectious pancreatic necrosis virus [117], parvovirus [118], duck plague herpesvirus [119], porcine parvovirus (PPV) [6], west Nile virus [120], H7N7 [121], hepatitis B virus (HBV) [122] |

| 1 month > t > 1 week | H11N6 [28], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [31], equine herpesvirus type-1 (EHV-1) [34], porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) [37], human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) [40], hepatitis C virus (HCV) [43], porcine sapovirus (SaV) [46], infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) [50], Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) [54], spumavirus [58], pepino mosaic virus (PepMV) [62], human parainfluenza viruses [63], lassa virus [67], venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) [67], sindbis virus [67], taura syndrome virus (TSV) [76], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [79], vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [82], nipah virus [86], hantavirus [88], severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) [91], H3N2 [94] |

| t < 1 week | Simian virus 40 (SV40) [29], lung–eye–trachea virus (LETV) [32], herpes simplex virus (HSV) [35], feline leukemia virus (FeLV) [38], invertebrate iridescent virus 6 (IIV-6) [41], ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) [44], lapinized rinderpest virus [47], mouse rotavirus (MRV) [51], infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [55], human polyomavirus (HPyVs) [59], potato virus Y (PVY) [62], suid herpesvirus-1 (SuHV-1) [64], human rhinovirus (HRV) [68], cytomegalovirus (CMV) [70], marburg virus [73], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [77], measles virus [80], middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [83] |

Fig. 2.

The distribution of the survival times of the 116 studied viruses [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122].

Existing studies have confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 is likely to exist for a long time in septic tanks and other soil-containing solid media, as well as in the ground [22]. The Singapore National Center for Infectious Diseases and the Defense Science Organization (DSO) National Laboratories have detected the virus in the residence rooms of COVID-2019 patients; floor surfaces had the highest positive viral signal, exceeding those of toilets, door handles, sinks, lockers, tables, and windows [12]. SARS-CoV-2 was found to remain viable in aerosols throughout the experiment (3 h), with a reduction in infectious titer from 103.5 to 102.7 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) per liter of air [77]. Based on these findings, SARS-CoV-2 may exist and survive for a long time in habitat and activity place of wildlife, especially in places with low temperatures and low levels of light.

4. Viral outbreaks in humans caused by direct contact with environmental media rather than contact with a natural host

By analyzing the literature published in the past 120 years, we found at least 198 viral infection cases with 28 different strains of viruses that occurred through direct contact with environmental media (Table 3 [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212], [213], [214], [215], [216], [217], [218], [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], [224], [225], [226], [227], [228], [229], [230], [231], [232], [233], [234], [235], [236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241], [242], [243], [244], [245], [246], [247], [248], [249], [250], [251], [252], [253], [254], [255], [256], [257], [258], [259], [260], [261], [262], [263], [264], [265], [266], [267], [268], [269], [270], [271], [272], [273], [274], [275], [276], [277], [278], [279], [280], [281], [282], [283], [284], [285], [286], [287], [288], [289], [290], [291], [292], [293], [294], [295], [296], [297], [298], [299], [300], [301], [302], [303], [304], [305], [306], [307], [308], [309], [310], [311], [312], [313], [314], [315], [316], [317], [318]). Some of these cases were statistically derived from data in order to obtain a correlation between environmental media and viral transmission, and many were derived from investigations of environmental media that recognized the route or host of viral transmission. For example:

Table 3.

Cases of virus infection caused by direct human contact with environmental media [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212], [213], [214], [215], [216], [217], [218], [219], [220], [221], [222], [223], [224], [225], [226], [227], [228], [229], [230], [231], [232], [233], [234], [235], [236], [237], [238], [239], [240], [241], [242], [243], [244], [245], [246], [247], [248], [249], [250], [251], [252], [253], [254], [255], [256], [257], [258], [259], [260], [261], [262], [263], [264], [265], [266], [267], [268], [269], [270], [271], [272], [273], [274], [275], [276], [277], [278], [279], [280], [281], [282], [283], [284], [285], [286], [287], [288], [289], [290], [291], [292], [293], [294], [295], [296], [297], [298], [299], [300], [301], [302], [303], [304], [305], [306], [307], [308], [309], [310], [311], [312], [313], [314], [315], [316], [317], [318].

| Virus | The relevant environmental media | Site, region, or country | Date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis E virus | Water | Kanpur, India | 1991 | [123] |

| Water | Hyderabad, India | 2005 | [124] | |

| Water | Shimla, India | 2015–2016 | [125] | |

| Water | Am Timan, Chad | 2016-09–2017-04 | [126] | |

| Water | Hyderabad, India | 2005-03–2005-08 | [127] | |

| Water | Zhejiang, China | 2014 | [128] | |

| Surface water | Darfur, Sudan | 2004 | [129] | |

| Water | Abbottabad, Pakistan | 1988 | [130] | |

| Drinking water | Nepal | 1995 | [131] | |

| Norovirus (Norwalk virus, a small round structured virus) | Groundwater, seawater | Italy | 2003 | [132] |

| Water | Guatemala | 2009 | [133] | |

| Well water | Northeast Wisconsin, USA | 2007-06 | [134] | |

| Water | Switzerland | 2008 | [135] | |

| Drinking water | The Netherlands | 2001-11–2001-12 | [136] | |

| Drinking water | Iceland | 2004 | [137] | |

| Water | A ski resort in New Zealand | 2006 | [138] | |

| Water | Kilkis, Northern Greece | 2012 | [139] | |

| Drinking water, shower water | Western Norway | 2002-07 | [140] | |

| Lake water | Western Finland | 2014-07 | [141] | |

| Drinking water | Northern Italy | 2009-06 | [142] | |

| Water | Belgium | 2007-07 | [143] | |

| Water | Chalkidiki, Greece | 2015-08 | [144] | |

| Drinking water | Podgorica, Montenegro | 2008-08 | [145] | |

| Tap water | China | 2010-10-31–2010-11-12 | [146] | |

| Lake water | Maine beach, USA | 2018 | [147] | |

| Environmental surface | Colorado, USA | 2019 | [148] | |

| Food | A hospital and an attached long-term care facility (LTCF), Japan | 2007 | [149] | |

| Pork liver and lamb chops | Taiwan, China | 2015-02 | [150] | |

| Water or food contaminated with water | A cruise ship sailing along the Yangtze River, China | 2014-04 | [151] | |

| Sandwich | Hamilton County, Ohio, USA | 1997 | [152] | |

| Water | Wuhan, China | 2017-04-28–2017-05-08 | [153] | |

| Well water | Northwest University of China, China | 2014-06 | [154] | |

| Water | Salzburg, Austria | 2005-05–2005-06 | [155] | |

| Bottled water | Jiaxing, China | 2014-02 | [156] | |

| Water | South Africa | 2017-01 | [157] | |

| Bottled water | Catalonia, Spain | 2016-04-11–2016-04-25 | [158] | |

| Food | Shanghai, China | 2012-12 | [159] | |

| Recreational water | Netherlands | 2002-06 | [160] | |

| Drinking water | Northeast Greece | 2006-06 | [161] | |

| Well water | Xanthi, Northern Greece | 2005 | [162] | |

| Groundwater | Jeju Island, Republic of Korea | 2004-05 | [163] | |

| Food | Quebec, Canada | 2011-01 | [164] | |

| Food | Nagasaki, Japan | 2003-11-18–2003-11-19 | [165] | |

| Swimming pool water | Southeast England | 2016-01 | [166] | |

| Recreational water | Vermont, USA | 2004-02 | [167] | |

| Swimming pool water | Galveston County, Texas, USA | 2013 | [168] | |

| Recreational water | Puerto Rico | 2009 | [169] | |

| Air | Southern Sweden | 2017–2018 | [170] | |

| Air | Lianyungang, China | 2017 | [171] | |

| Ice | Taiwan, China | 2015 | [172] | |

| Food | Zhuhai, China | 2011 | [173] | |

| Food | Beijing, China | 2017-12 | [174] | |

| Water | Wuxi, China | 2014-12-11 | [175] | |

| Well water | Hebei, China | 2014–2015 | [176] | |

| Food | Shanghai, China | 2013-12 | [177] | |

| Food | Beijing, China | 2018-09-04 | [178] | |

| Food | Seven-day holiday cruise from Florida, USA to the Caribbean | 2002-11 | [179] | |

| Environmental surface | A 240-bed veterans LTCF, USA | 2003-01–2003-02 | [180] | |

| Well water | Sweden | Easter 2009 | [181] | |

| Well water | Santo Stefano Quisquina, Sicily, Italy | 2011-03 | [182] | |

| Water | Nokia City, Finland | 2007-11 | [183] | |

| Ice | Delaware, USA | 1987-09-19–1987-09-27 | [184] | |

| Food | Hamburg, Germany | 2005-08 | [185] | |

| Tap water | Hemiksem, Belgium | 2010-12 | [186] | |

| Environmental surface | An international cruise ship | 2008 | [187] | |

| Public toilet environment | Cruise ships | 2005–2008 | [188] | |

| Water, environmental surface | A cruise ship, Europe | Summer of 2006 | [189] | |

| Dirty computer equipment (i.e., keyboard and mouse) | District of Columbia, USA | 2007-02-08 | [190] | |

| Environmental surface | Shanghai, China | 2014-12-7–2014-12-18 | [191] | |

| Food | A football game in the University of Florida, USA | 1998-09 | [192] | |

| Food | West Virginia, USA | 2006-01 | [193] | |

| Water | Shenzhen, China | 2009-09-17–2009-10-03 | [194] | |

| Food | Stockholm County, Sweden | 2007-11 | [195] | |

| Tap water | Taranto Bay, Southern Italy | 2000-07 | [196] | |

| Swimming pool water | Ohio, USA | 1977-06 | [197] | |

| Tap water | Heinävesi, Finland | 1998-03 | [198] | |

| Food | New York, USA | 2000-02 | [199] | |

| Drinking water | Northern Georgia, USA | 1980-08 | [200] | |

| Food | A hotel in Virginia, USA | 2000-11 | [201] | |

| Food | Virginia, USA | 1999-05–1999-06 | [202] | |

| Environment | Southern Finland | 1999-12–2000-02 | [203] | |

| Well water | Arizona, USA | 1989-04-17–1989-05-01 | [204] | |

| Water | Pennsylvania, USA | 1978-07 | [205] | |

| Aerosol | A primary school and nursery | 2001-06 | [206] | |

| Water | A ski resort in Sweden | 2002-02–2002-03 | [207] | |

| Food | Southern Sweden | 2000-05-02–2000-05-03 | [208] | |

| Food | Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas, USA | 1998-08-27–1998-09-01 | [209] | |

| Aerosol | A large hotel, Canada | 1998-12 | [210] | |

| Water vapor | Ontinyent (Valencia), Spain | 1992-01 | [211] | |

| Recreational water | The Netherlands | 2012-08 | [212] | |

| Drinking water | Finland | 1994-04 | [213] | |

| Food (made from drinking water) | South Dakota, USA | 1986-08-30–1986-08-31 | [214] | |

| Water | North Georgia, USA | 1982-01 | [215] | |

| Water, food | Two Caribbean cruise ships | 1986-04-26–1986-05-10 | [216] | |

| Lake water | Markham County, Michigan, USA | 1979-07-13–1979-07-16 | [217] | |

| Food (exposure to non-drinking water) | The US Air Force Academy, USA | [218] | ||

| Fomite | Sydney, Australia | 2002-09 | [219] | |

| Environment | North West England | 1996-01–1996-05 | [220] | |

| Food | Metropolitan Concert Hall, UK | 1999-01 | [221] | |

| Food | Toyota City, Japan | 1989-03 | [222] | |

| Food | A Massachusetts university, USA | 1994-12 | [223] | |

| Air | Los Angeles, USA | 1988-12–1989-01 | [224] | |

| Well water | A restaurant in the Yukon territory in Canada | 1995 | [225] | |

| Groundwater | La Neuveville, Switzerland | 1998 | [226] | |

| Tap water | A re-education ward | 1999-01 | [227] | |

| Food made from contaminated water | South Wales and Bristol, UK | 1994-08 | [228] | |

| Air | A British registered cruise ship | 1988-01-13 | [229] | |

| River water | Southern New South Wales, Australia | Christmas holiday period of 1989 | [230] | |

| Raw oysters | Southwest Scotland | Christmas holiday period of 1993 | [231] | |

| Aerosol | An elderly care unit, UK | 1992-11 | [232] | |

| Environment | A hospital for the mentally infirm, UK | 1994-05 | [233] | |

| Food | A large hotel, UK | 1985-11 | [234] | |

| Hepatitis A virus | Drinking water | Mead County, Kentucky, USA | 1982-11 | [235] |

| Well water | A trailer park in Bartow County, Georgia, USA | 1982 | [236] | |

| Lake water | Wateree Lake, USA | 1969-09 | [237] | |

| Water | Albania | 2002-11–2003-01 | [238] | |

| Bread | A village in South Cambridgeshire, England | The late spring and summer of 1989 | [239] | |

| Groundwater | USA | 1971–2017 | [240] | |

| Food | The Netherlands | 2017 | [241] | |

| Food | Italy | 1996 | [242] | |

| Shellfish | Shanghai, China | 1988 | [243] | |

| Well water | Guangxi, China | 2012-05 | [244] | |

| Food | Southern Italy | 2002 | [245] | |

| Groundwater | Thailand | 2000 | [246] | |

| Water | Rudraprayag District of Uttarakhand State, India | 2013-05 | [247] | |

| Water | Georgetown, Texas, USA | 1980-06 | [248] | |

| Frozen berries | Northern Italy | 2013 | [249] | |

| Clams | Valencia, Spain | 1999 | [250] | |

| Water | Orleans Island in the St. Lawrence River, Canada | Summer of 1995 | [251] | |

| Swimming pool water | USA | 1989 | [252] | |

| Spa pool | Victoria, USA | 1997 | [253] | |

| Water | Republic of Korea | 2015-04 | [254] | |

| Water | Arapiles 62 camp located in Castellciutat, near Seo de Urgel, Spain | 1987-09 | [255] | |

| Drinking water | A medical college student’s hostel, New Delhi, India | 2014-01 | [256] | |

| Orange juice | Europe | 2004 | [257] | |

| Frozen strawberries | Nordic countries | 2012-10–2013-06-27 | [258] | |

| Frozen mixed berries | Northern Italy | 2013-01–2013-05 | [259] | |

| Semi-dried tomato | The Netherlands | 2010 | [260] | |

| Pomegranate | USA | 2013-05 | [261] | |

| Hepatitis C virus | Water | Medea, Algeria | 1980–1981 | [262] |

| Wastewater | Sewage treatment plant, Algeria | 1991 | [263] | |

| Parvovirus | Drinking water | USA | 1971–1978 | [264] |

| Measles virus | Air | The Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area, USA | 1991-07 | [265] |

| Poliovirus | Milk | West coast of USA | 1943-09 | [266] |

| Lake water | Oakland County, Michigan, USA | 1993-06-11–1993-06-13 | [267] | |

| Droplet | Middlesex Hospital, London, UK | Late summer of 1952 | [268] | |

| H5N1 | Chicken manure | Indonesia | 2005-06–2008-06 | [269] |

| Rotavirus | Tap water | Isere region, France | 1994 | [270] |

| Well water | India | 2009-04–2009-05 | [271] | |

| Water | Eagle-Vail, Colorado, USA | 1981-03 | [272] | |

| Aerosol | A primary school | [273] | ||

| Adenovirus | Swimming pool water | Oklahoma, USA | 1982-07 | [274] |

| Environment | The marine corps recruit training command, San Diego, USA | 2004 | [275] | |

| Air | Wuhan, China | 2014 | [276] | |

| Swimming pool water | Georgia, USA | 1977 | [277] | |

| Swimming pool water | Beijing, China | 2013 | [278] | |

| Swimming facilities | Taiwan, China | 2011-09 | [279] | |

| Hantavirus | Animal feces | North Dakota, USA | 2016 | [280] |

| Deer mouse excreta | California, USA | 2017 | [281] | |

| Animal secretions | North Wales | 2013 | [282] | |

| Rat | Illinois and Wisconsin, USA | 2017 | [283] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Saliva | Hong Kong, China | 2020 | [284] |

| MERS-CoV | Camel | The United Arab Emirates | 2019 | [285] |

| Droplet | Saudi Arabia | 2013-03–2013-04 | [286] | |

| Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus | Cat | Japan | [287] | |

| Herpes simplex virus | Saliva | England | 2019 | [288] |

| SARS-CoV-1 | Bat | Yunnan, China | 2015 | [289] |

| Aerosol | Canada | 2003 | [290] | |

| Aerosol | Hong Kong, China | 2003 | [291] | |

| Air | Canada | 2003 | [292] | |

| Air | Hong Kong, China | 2003 | [293] | |

| West Nile virus | Mosquito-controlled pool | California | 2007 | [294] |

| H3N2 | Pig | Ohio, USA | 2012 | [295] |

| Air, droplets | Alaska, USA | 1977 | [296] | |

| H1N1 | Droplet | Sichuan, China | 2009 | [297] |

| H7N7 | Poultry, human | The Netherlands | 2003-02 | [298] |

| Nipah virus | Raw date palm sap | Tangail District, Bangladesh | 2004–2005 | [299] |

| Hepatitis B virus | Foot care | Los Angeles, USA | 2008 | [300] |

| Human calicivirus | Well water | Wyoming, USA | 2001-01 | [301] |

| Echovirus | Swimming pool water | Kassel, Germany | 2001-07–2001-10 | [302] |

| Swimming pool water | Rome, Italy | 1997 | [303] | |

| Ebola virus | Body fluid | Congo | 1995 | [304] |

| Body fluid | Congo | 1995 | [305] | |

| Marburg virus | Bat or bat secretions | Uganda | 2007-06–2007-09 | [306] |

| Bat or bat secretions | The Netherlands | 2008 | [307] | |

| Bat secretions | USA | 2008 | [308] | |

| Cave, mine, or similar habitat | Congo | 1998-10 | [309] | |

| Patient’s body or secretion | Uganda | 2012-09–2012-12 | [310] | |

| Enterovirus | Irrigation wastewater | Israel | 1980–1981 | [311] |

| Drinking water | Switzerland | 1998-08 | [312] | |

| Seawater | Connecticut, USA | 2004 | [313] | |

| Food | England | 2003-04 | [314] | |

| Well water | Southern Missouri and Arkansas, USA | 1978-05-07–1978-05-26 | [315] | |

| Drinking water | Colorado, USA | 1976-12 | [316] | |

| Hepatitis virus | Water | Austria | 1952 | [317] |

| Water | France | 1957-09-08–1957-10-05 | [318] | |

(1) A 44-year-old woman from Colorado, USA, suffered from Marburg disease in 2008 after returning home from a two-week tour in Uganda. This disease is caused by a virus that belongs to the same family as the Ebola virus, one of the deadliest pathogens to humans. Scientists sequenced the gene of an Egyptian fruit bat in a cave in Uganda and believed that she was infected by the virus when she touched a rock covered with bat feces while visiting the python cave [8], [9], [10].

(2) The transmission route of the Ebola virus has been confirmed as the human consumption of fruit contaminated by fruit bat feces [7].

(3) No less than five infectious disease incidents have occurred in China since 2009 due to drinking groundwater containing a virus that ended up affecting thousands of people. For example, an outbreak of gastroenteritis occurred in Hebei, China, in the winter of 2014–2015. The nucleotide sequence of the norovirus extracted from clinical and water samples had 99% homology with the strain of Beijing/CHN/2015, which confirmed that the outbreak was waterborne. This is an excellent example of finding the route of virus transmission by investigating environmental media [154], [176], [194], [244], [319].

(4) Airborne transmission is an important mode of virus transmission, and at least six different cases of viruses infecting humans through airborne transmission have been reported. Alsved and colleagues took air samples from the surrounding environment of patients with norovirus infection and analyzed the norovirus RNA in the samples by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). They detected norovirus RNA in some air samples, suggesting that air pollution from vomiting is an important source of norovirus [170], [265], [273], [276], [292], [295].

Insights from a statistical perspective provide evidence for linkages between the environment and epidemics:

(1) Eight out of the 11 first reported human cases of Ebola occurred in areas with high levels of forest destruction, where the forests were the habitats of bats carrying the Ebola virus [320].

(2) The migration trajectory of ticks in damaged forest areas is significantly correlated to the distribution and morbidity of Kyasanur forest disease [321] and Lyme disease [322]. Moreover, habitat destruction increases both the survival pressure of wild animals and the viral load of urine and saliva secretions [323].

5. Viruses in many animals might transmit to humans through multiple pathways

The order Nidovirales, sub-family Orthocoronavirinae, family Coronaviridae is composed of four genera: α-coronavirus, β-coronavirus, γ-coronavirus, and δ-coronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the subgenus Sarbecovirus of the genus β-coronavirus, to which SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV also belong. Coronaviruses (CoVs) infect humans as well as domestic and wild animal species, with infections remaining sub-clinical in most cases [324], [325], [326]. α-coronavirus and β-coronavirus usually infect mammals, with a probable origin of bats, while γ-coronavirus and δ-coronavirus mainly infect birds, and sometimes mammals, and might originate from swine [327], [328], [329]. A long list of animal species has been reported as intermediate hosts, such as dogs, cats, cattle, horses, camels, rodents, rabbits, pangolins, mink, snakes, frogs, marmots, hedgehogs, and ferrets [324], [330], [331], [332], [333], [334], [335], [336]. Thus, there could be multiple viral transmission pathways from different animals to humans. The three outbreak points of coronavirus in China—namely, the livestock markets in Guangdong in 2003, the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan at the end of 2019, and the Xinfadi Seafood Market in Beijing in June 2020—are all related to animal markets. Civet cats and camels have been demonstrated to transmit SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV to humans, which provides an important hint of virus transmission directly from animals. However, it remains unclear which animal could be the main intermediate host of SARS-CoV-2, although positive viral RNA signals were detected in seafood markets and on the chopping boards of salmon. In 1983, Lidgerding and Hetrick [337] first reported the replication of a coronavirus in a fish cell line. Furthermore, Sano et al. [338] successfully isolated a coronavirus from common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in 1988, which induced hepatic, renal, and intestinal necrosis in experimentally infected fish. Miyazaki et al. [339] found a corona-like virus in color carp (Cyprinus carpio) in 2000, which caused dermal lesion and necrosis in internal organs.

Based on the aforementioned pieces of evidence, we propose that an environmental quasi-host can infect a human, and that there are two transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2:

(1) Natural hosts (animals with the virus)–environmental quasi-host (animal feces/water, soil and food contaminated by animals’ urine, saliva, feces, and secretions)–patient zero (infected or virus-carrying human who came into contact with the environmental quasi-host while traveling or working in the wild)–back to home or human habitations–outbreak of COVID-19.

(2) Natural host (animals with the virus)–environmental quasi-host (fruit, food, or meat contaminated by animals’ urine, saliva, feces, and secretions)–transported to different regions or countries–patient zero (infected or virus-carrying human who came into contact with or ate the environmental quasi-host)–outbreak of COVID-19.

To summarize, it is imperative to investigate environmental quasi-hosts in order to source track the origin of SARS-CoV-2 through our two suggested transmission routes. Given the need to trace the virus around the world to prevent further pandemics, global collaboration is required not only to identify the origin of the virus, but also to fundamentally protect the existence and development of species. Doing so will proactively conserve and restore habitats for species, and serve as a key strategy for preempting the next pandemic.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the fund by Chinese Academy of Engineering (2020-ZD-15) for financial support of this work.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Miao Li, Yunfeng Yang, Yun Lu, Dayi Zhang, Yi Liu, Xiaofeng Cui, Lei Yang, Ruiping Liu, Jianguo Liu, Guanghe Li, and Jiuhui Qu declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Konda M., Dodda B., Konala V.M., Naramala S., Adapa S. Potential zoonotic origins of SARS-CoV-2 and insights for preventing future pandemics through one health approach. Cureus. 2020;12(6) doi: 10.7759/cureus.8932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam T.T.Y., Jia N., Zhang Y.W., Shum M.H.H., Jiang J.F., Zhu H.C. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583(7815):282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y., Peng F., Wang R., Guan K., Jiang T., Xu G. The deadly coronaviruses: the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J Autoimmun. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biziagos E., Passagot J., Crance J.M., Deloince R. Long-term survival of hepatitis A virus and poliovirus type 1 in mineral water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54(11):2705–2710. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.11.2705-2710.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauppinen A., Pitkänen T., Miettinen I.T. Persistent norovirus contamination of groundwater supplies in two waterborne outbreaks. Food Environ Virol. 2018;10(1):39–50. doi: 10.1007/s12560-017-9320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bøtner A., Belsham G.J. Virus survival in slurry: analysis of the stability of foot-and-mouth disease, classical swine fever, bovine viral diarrhoea and swine influenza viruses. Vet Microbiol. 2012;157(1–2):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leroy E.M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438(7068):575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christenson J.C., Fischer P.R. Beware of bat caves! Marburg hemorrhagic fever in a traveler. Travel Med Advisor. 2010;20(4):21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amman B.R., Carroll S.A., Reed Z.D., Sealy T.K., Balinandi S., Swanepoel R. Seasonal pulses of Marburg virus circulation in juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus bats coincide with periods of increased risk of human infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flyak A.I. Vanderbilt University; Nashville: 2016. The analysis of the human antibody response to filovirus infection [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y., Ning Z., Chen Y., Guo M., Liu Y., Gali N.K. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582(7813):557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong S.W.X., Tan Y.K., Chia P.Y., Lee T.H., Ng O.T., Wong M.S.Y. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallapaty S. How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak. Nature. 2020;580(7802):176–177. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fongaro G, Hermes Stoco P, Sobral Marques Souza D, Grisard EC, Magri ME, Rogovski P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in human sewage in Santa Catalina, Brazil, November 2019. 2020. medRxiv 2020.06.26.2014731.

- 15.Iaconelli M, Bonanno Ferraro G, Mancini P, Veneri C. CS N°39/2020 - Studio ISS su acque di scarico, a Milano e Torino Sars-Cov-2 presente già a dicembre [Internet]. Rome: Istituto Superiore di Sanità; 2020 Jun 18 [Cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.iss.it/web/guest/primo-piano/-/asset_publisher/o4oGR9qmvUz9/content/id/5422725. Italian.

- 16.Wurtzer S, Marechal V, Mouchel J-M, Maday Y, Teyssou R, Richard E, et al. Evaluation of lockdown impact on SARS-CoV-2 dynamics through viral genome quantification in Paris wastewaters. 2020. medRxiv 2020.04.12.20062679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Agence France-Presse (AFP). Paris finds ‘minuscule traces’ of coronavirus in its non-potable water [Internet]. Dubai: Al Arabiya Network; 2020 Apr 20 [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://english.alarabiya.net/en/coronavirus/2020/04/20/Paris-finds-minuscule-traces-of-coronavirus-in-its-non-potable-water.html.

- 18.CGTN. Coronavirus found on shrimp packaging from Ecuador, China suspends imports from 23 meat companies [Internet]. Beijing: China Global Television Network (CGTN); 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-07-10/Coronavirus-found-on-packages-of-shrimps-imported-from-Ecuador-S0O7fXvw4M/index.html.

- 19.Cui H. Coronavirus pandemic: 6 new Beijing cases traced to food market [Internet]. Beijing: China Global Television Network (CGTN); 2020 Jun 13 [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://news.cgtn.com/news/7855444f7a514464776c6d636a4e6e62684a4856/index.html.

- 20.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan Y., Zhang D., Yang P., Poon L.L.M., Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D, Yang Y, Huang X, Jiang J, Li M, Zhang X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spillover into hospital outdoor environments. 2020. medRxiv 2020.05.12.20097105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Legendre M., Lartigue A., Bertaux L., Jeudy S., Bartoli J., Lescot M. In-depth study of Mollivirus sibericum, a new 30,000-y-old giant virus infecting Acanthamoeba. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(38):E5327–E5335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510795112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst C.J., Gerba C.P., Cech I. Effects of environmental variables and soil characteristics on virus survival in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40(6):1067–1079. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.6.1067-1079.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seitz S.R., Leon J.S., Schwab K.J., Lyon G.M., Dowd M., McDaniels M. Norovirus infectivity in humans and persistence in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(19):6884–6888. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05806-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDaniels A.E., Cochran K.W., Gannon J.J., Williams G.W. Rotavirus and reovirus stability in microorganism-free distilled and waste waters. Water Res. 1983;17(10):1349–1353. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abad F.X., Pintó R.M., Villena C., Gajardo R., Bosch A. Astrovirus survival in drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(8):3119–3122. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3119-3122.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zarkov I.S. Survival of avian influenza viruses in filtered and natural surface waters of different physical and chemical parameters. Rev Med Vet. 2006;157(10):471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akers T.G., Prato C.M., Dubovi E.J. Airborne stability of simian virus 40. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26(2):146–148. doi: 10.1128/am.26.2.146-148.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahne W. Comparative studies of the stability of 4 fish-pathogenic viruses (VHSV, PFR, SVCV, IPNV). Zentralbl Veterinarmed B 1982;29(6):457–76. German. [PubMed]

- 31.Wu S., Yan Y., Yan P., Den Y., Chen L. Study on the survival ability of HIV in the micro environment of biological safety laboratory. Chin J Exp Clin Virol. 2014;28(6):426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curry S.S., Brown D.R., Gaskin J.M., Jacobson E.R., Ehrhart L.M., Blahak S. Persistent infectivity of a disease-associated herpesvirus in green turtles after exposure to seawater. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36(4):792–797. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-36.4.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawley L.M., Garver K.A. Stability of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in freshwater and seawater at various temperatures. Dis Aquat Organ. 2008;82(3):171–178. doi: 10.3354/dao01998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dayaram A., Franz M., Schattschneider A., Damiani A.M., Bischofberger S., Osterrieder N. Long term stability and infectivity of herpesviruses in water. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):46559. doi: 10.1038/srep46559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Firquet S., Beaujard S., Lobert P.E., Sané F., Caloone D., Izard D. Survival of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses on inanimate surfaces. Microbes Environ. 2015;30(2):140–144. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung H., Sobsey M.D. Comparative survival of indicator viruses and enteric viruses in seawater and sediment. Water Sci Technol. 1993;27(3–4):425–428. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dee S.A., Martinez B.C., Clanton C. Survival and infectivity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in swine lagoon effluent. Vet Rec. 2005;156(2):56–57. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.2.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francis D.P., Essex M., Gayzagian D. Feline leukemia virus: survival under home and laboratory conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9(1):154–156. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.1.154-156.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butot S., Putallaz T., Sánchez G. Effects of sanitation, freezing and frozen storage on enteric viruses in berries and herbs. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;126(1–2):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding D.C., Chang Y.C., Liu H.W., Chu T.Y. Long-term persistence of human papillomavirus in environments. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(1):148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernández A., Marina C.F., Valle J., Williams T. Persistence of invertebrate iridescent virus 6 in tropical artificial aquatic environments. Brief report. Arch Virol. 2005;150(11):2357–2363. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurst C.J., Benton W.H., McClellan K.A. Thermal and water source effects upon the stability of enteroviruses in surface freshwaters. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35(4):474–480. doi: 10.1139/m89-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doerrbecker J., Behrendt P., Mateu-Gelabert P., Ciesek S., Riebesehl N., Wilhelm C. Transmission of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs: viral stability and association with drug preparation equipment. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(2):281–287. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hick P., Evans O., Looi R., English C., Whittington R.J. Stability of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) and assessment of disinfection of seawater and oyster tissues using a bioassay. Aquaculture. 2016;450:412–421. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arthur S.E., Gibson K.E. Environmental persistence of Tulane virus—a surrogate for human norovirus. Can J Microbiol. 2016;62(5):449–454. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2015-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esseili M.A., Saif L.J., Farkas T., Wang Q. Feline calicivirus, murine norovirus, porcine sapovirus, and tulane virus survival on postharvest lettuce. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(15):5085–5092. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00558-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hyslop N.S.G. Observations on the survival and infectivity of airborne rinderpest virus. Int J Biometeorol. 1979;23(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01553371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broadbent L., Fletcher J.T. The epidemiology of tomato mosaic: IV. persistence of virus on clothing and glasshouse structures. Ann Appl Biol. 1963;52(2):233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damgaardlarsen S., Jensen K.O., Lund E., Nissen B. Survival and movement of enterovirus in connection with land disposal of sludges. Water Res. 1977;11(6):503–508. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guan J., Chan M., Brooks B.W., Spencer J.L. Infectious bursal disease virus as a surrogate for studies on survival of various poultry viruses in compost. Avian Dis. 2010;54(2):919–922. doi: 10.1637/9115-102209-ResNote.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ijaz M.K., Sattar S.A., Alkarmi T., Dar F.K., Bhatti A.R., Elhag K.M. Studies on the survival of aerosolized bovine rotavirus (UK) and a murine rotavirus. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;17(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown P., Gajdusek D.C. Survival of scrapie virus after 3 years’ interment. Lancet. 1991;337(8736):269–270. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90873-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baert L., Uyttendaele M., Vermeersch M., Van Coillie E., Debevere J. Survival and transfer of murine norovirus 1, a surrogate for human noroviruses, during the production process of deep-frozen onions and spinach. J Food Prot. 2008;71(8):1590–1597. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.8.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricklin M.E., García-Nicolás O., Brechbühl D., Python S., Zumkehr B., Nougairede A. Vector-free transmission and persistence of Japanese encephalitis virus in pigs. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):10832. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordan F.T., Nassar T.J. The survival of infectious bronchitis (IB) virus in water. Avian Pathol. 1973;2(2):91–101. doi: 10.1080/03079457309353787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paek M.R., Lee Y.J., Yoon H., Kang H.M., Kim M.C., Choi J.G. Survival rate of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses at different temperatures. Poult Sci. 2010;89(8):1647–1650. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bibby K., Casson L.W., Stachler E., Haas C.N. Ebola virus persistence in the environment: state of the knowledge and research needs. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2015;2(1):2–6. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lotlikar M.S., Lipson S.M. Survival of spumavirus, a primate retrovirus, in laboratory media and water. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;211(2):207–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang L., Goh S.G., Gin K.Y.H. Decay kinetics of microbial source tracking (MST) markers and human adenovirus under the effects of sunlight and salinity. Sci Total Environ. 2017;574:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown J.D., Swayne D.E., Cooper R.J., Burns R.E., Stallknecht D.E. Persistence of H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses in water. Avian Dis. 2007;51(1 Suppl):285–289. doi: 10.1637/7636-042806R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stallknecht D.E., Shane S.M., Kearney M.T., Zwank P.J. Persistence of avian influenza viruses in water. Avian Dis. 1990;34(2):406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehle N., Gutiérrez-Aguirre I., Prezelj N., Delic D., Vidic U., Ravnikar M. Survival and transmission of potato virus Y, pepino mosaic virus, and potato spindle tuber viroid in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(4):1455–1462. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03349-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parkinson A.J., Muchmore H.G., Scott E.N., Scott L.V. Survival of human parainfluenza viruses in the South Polar environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(4):901–905. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.4.901-905.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paluszak Z., Lipowski A., Ligocka A. Survival rate of Suid herpesvirus (SuHV-1, Aujeszky’s disease virus, ADV) in composted sewage sludge. Pol J Vet Sci. 2012;15(1):51–54. doi: 10.2478/v10181-011-0113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dublineau A., Batéjat C., Pinon A., Burguière A.M., Leclercq I., Manuguerra J.C. Persistence of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus in water and on non-porous surface. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lebarbenchon C., Yang M., Keeler S.P., Ramakrishnan M.A., Brown J.D., Stallknecht D.E. Viral replication, persistence in water and genetic characterization of two influenza A viruses isolated from surface lake water. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sagripanti J.L., Rom A.M., Holland L.E. Persistence in darkness of virulent alphaviruses, Ebola virus, and Lassa virus deposited on solid surfaces. Arch Virol. 2010;155(12):2035–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reagan K.J., McGeady M.L., Crowell R.L. Persistence of human rhinovirus infectivity under diverse environmental conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41(3):618–620. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.3.618-620.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graiver D.A., Topliff C.L., Kelling C.L., Bartelt-Hunt S.L. Survival of the avian influenza virus (H6N2) after land disposal. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(11):4063–4067. doi: 10.1021/es900370x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stowell J.D., Forlin-Passoni D., Radford K., Bate S.L., Dollard S.C., Bialek S.R. Cytomegalovirus survival and transferability and the effectiveness of common hand-washing agents against cytomegalovirus on live human hands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(2):455–461. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03262-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shoham D., Jahangir A., Ruenphet S., Takehara K. Persistence of avian influenza viruses in various artificially frozen environmental water types. Influenza Res Treat. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/912326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang H., Li Y., Chen J., Chen Q., Chen Z. Perpetuation of H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses in natural water bodies. J Gen Virol. 2014;95(Pt 7):1430–1435. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.063438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belanov EF, Muntianov VP, Kriuk VD, Sokolov AV, Bormotov NI, P’iankov OV, et al. Survival of Marburg virus infectivity on contaminated surfaces and in aerosols. Vopr Virusol 1996;41(1):32–4. Russian. [PubMed]

- 74.Calnek B.W., Hitchner S.B. Survival and disinfection of Marek’s disease virus and the effectiveness of filters in preventing airborne dissemination. Poult Sci. 1973;52(1):35–43. doi: 10.3382/ps.0520035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Casanova L., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009;43(7):1893–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oidtmann B., Dixon P., Way K., Joiner C., Bayley A.E. Risk of waterborne virus spread—review of survival of relevant fish and crustacean viruses in the aquatic environment and implications for control measures. Rev Aquacult. 2018;10(3):641–669. [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cottral G.E. Persistence of foot-and-mouth disease virus in animals, their products and the environment. Bull Off Int Epizoot. 1969;71(3–4):549–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang X.W., Li J.S., Jin M., Zhen B., Kong Q.X., Song N. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J Virol Methods. 2005;126(1–2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.De Jong J.G., Winkler K.C. Survival of measles virus in air. Nature. 1964;201(4923):1054–1055. doi: 10.1038/2011054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.St-Hilaire S., Beevers N., Way K., Le Deuff R.M., Martin P., Joiner C. Reactivation of koi herpesvirus infections in common carp Cyprinus carpio. Dis Aquat Organ. 2005;67(1–2):15–23. doi: 10.3354/dao067015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zimmer B., Summermatter K., Zimmer G. Stability and inactivation of vesicular stomatitis virus, a prototype rhabdovirus. Vet Microbiol. 2013;162(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Munster V.J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(38):20590. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harcourt D.G., Cass L.M. Persistence of a granulosis virus of Pieris rapae in soil. J Invertebr Pathol. 1968;11(1):142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Escudero B.I., Rawsthorne H., Gensel C., Jaykus L.A. Persistence and transferability of noroviruses on and between common surfaces and foods. J Food Prot. 2012;75(5):927–935. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smither S.J., Eastaugh L.S., Findlay J.S., O’Brien L.M., Thom R., Lever M.S. Survival and persistence of Nipah virus in blood and tissue culture media. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):1760–1762. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1698272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis-Fields M.K., Allison A.B., Brown J.R., Poulson R.L., Stallknecht D.E. Effects of temperature and pH on the persistence of avian paramyxovirus-1 in water. J Wildl Dis. 2014;50(4):998–1000. doi: 10.7589/2014-04-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kallio E.R., Klingström J., Gustafsson E., Manni T., Vaheri A., Henttonen H. Prolonged survival of Puumala hantavirus outside the host: evidence for indirect transmission via the environment. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(Pt 8):2127–2134. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81643-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Demangeat G., Voisin R., Minot J.C., Bosselut N., Fuchs M., Esmenjaud D. Survival of Xiphinema index in vineyard soil and retention of Grapevine fanleaf virus over extended time in the absence of host plants. Phytopathology. 2005;95(10):1151–1156. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-95-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Friedrich R., Kaemmerer D., Seigner L. Investigation of the persistence of Beet necrotic yellow vein virus in rootlets of sugar beet during biogas fermentation. J Plant Dis Prot. 2010;117(4):150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang Q., Li J., Jiang X., Li C., Liu L., Liang M. A primary study of the thermal stability and inactivation of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Chin J Exp Clin Virol. 2014;28(3):206–208. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bitterlin M.W., Gonsalves D. Spatial distribution of Xiphinema rivesi and persistence of tomato ringspot virus and its vector in soil. Plant Dis. 1987;71(5):408–411. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Graham D.A., Staples C., Wilson C.J., Jewhurst H., Cherry K., Gordon A. Biophysical properties of salmonid alphaviruses: influence of temperature and pH on virus survival. J Fish Dis. 2007;30(9):533–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thomas Y., Vogel G., Wunderli W., Suter P., Witschi M., Koch D. Survival of influenza virus on banknotes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(10):3002–3007. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00076-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environ Virol. 2009;1(1):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thompson C.G., Scott D.W., Wickman B.E. Long-term persistence of the nuclear polyhedrosis virus of the Douglas-fir tussock moth, Orgyia pseudotsugata (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae), in forest soil. Environ Entomol. 1981;10(2):254–255. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huq F. Effect of temperature and relative humidity on variola virus in crusts. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54(6):710–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karalyan Z., Avetisyan A., Avagyan H., Ghazaryan H., Vardanyan T., Manukyan A. Presence and survival of African swine fever virus in leeches. Vet Microbiol. 2019;237 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Espinosa A.C., Mazari-Hiriart M., Espinosa R., Maruri-Avidal L., Méndez E., Arias C.F. Infectivity and genome persistence of rotavirus and astrovirus in groundwater and surface water. Water Res. 2008;42(10–11):2618–2628. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mebus C.A., House C., Gonzalvo F.R., Pineda J.M., Tapiador J., Pire J.J. Survival of swine vesicular disease virus in Spanish Serrano cured hams and Iberian cured hams, shoulders and loins. Food Microbiol. 1993;10(3):263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Munro J., Bayley A.E., McPherson N.J., Feist S.W. Survival of frog virus 3 in freshwater and sediment from an English lake. J Wildl Dis. 2016;52(1):138–142. doi: 10.7589/2015-02-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Momoyama K. Survival of baculoviral mid-gut gland necrosis virus (BMNV) in infected tissues and in sea water. Fish Pathol. 1989;24(3):179–181. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jones T.H., Muehlhauser V. Survival of Porcine teschovirus as a surrogate virus on pork chops during storage at 2 °C. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;194:21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ogaard L., Williams C.F., Payne C.C., Zethner O. Activity persistence of granulosis viruses [Baculoviridae] in soils in United Kingdom and Denmark. Entomophaga. 1988;33(1):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kumar S.S., Bharathi R.A., Rajan J.J.S., Alavandi S.V., Poornima M., Balasubramanian C.P. Viability of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in sediment during sun-drying (drainable pond) and under non-drainable pond conditions indicated by infectivity to shrimp. Aquaculture. 2013;402:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pietsch J.P., Amend D.F., Miller C.M. Survival of infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus held under various environmental conditions. J Fish Res Board Can. 1977;34(9):1360–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leiva-Rebollo R., Labella A.M., Valverde E.J., Castro D., Borrego J.J. Persistence of lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV) in seawater. Food Environ Virol. 2020;12(2):174–179. doi: 10.1007/s12560-020-09420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Long P.H., Olitsky P.K. Effect of cysteine on the survival of vaccine virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1930;27(5):380–381. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miles S.L., Takizawa K., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of infectious prions in water. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2011;46(9):938–943. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2011.586247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mor S.K., Verma H., Sharafeldin T.A., Porter R.E., Ziegler A.F., Noll S.L. Survival of turkey arthritis reovirus in poultry litter and drinking water. Poult Sci. 2015;94(4):639–642. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nath Srivastava R., Lund E. The stability of bovine parvovirus and its possible use as an indicator for the persistence of enteric viruses. Water Res. 1980;14(8):1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Olszewska H., Paluszak Z., Jarzabek Z. Survival of bovine enterovirus strain LCR-4 in water, slurry, and soil. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2008;52(2):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Parashar D., Khalkar P., Arankalle V.A. Survival of hepatitis A and E viruses in soil samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(11):E1–E4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Plumb J.A., Wright L.D., Jones V.L. Survival of channel catfish virus in chilled, frozen, and decomposing channel catfish. Prog Fish Cult. 1973;35(3):170–172. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Savage C.E., Jones R.C. The survival of avian reoviruses on materials associated with the poultry house environment. Avian Pathol. 2003;32(4):419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tapia E., Monti G., Rozas M., Sandoval A., Gaete A., Bohle H. Assessment of the in vitro survival of the infectious salmon anaemia virus (ISAV) under different water types and temperature. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 2013;33(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tu K.C., Spendlove R.S., Goede R.W. Effect of temperature on survival and growth of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. Infect Immun. 1975;11(6):1409–1412. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.6.1409-1412.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Uttenthal A., Lund E., Hansen M. Mink enteritis parvovirus. Stability of virus kept under outdoor conditions. APMIS. 1999;107(3):353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wolf K., Burke C.N. Survival of duck plague virus in water from Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge, South Dakota. J Wildl Dis. 1982;18(4):437–440. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-18.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mather T., Takeda T., Tassello J., Ohagen A., Serebryanik D., Kramer E. West Nile virus in blood: stability, distribution, and susceptibility to PEN110 inactivation. Transfusion. 2003;43(8):1029–1037. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu H., Xiong C., Chen J., Chen G., Zhang J., Li Y. Two genetically diverse H7N7 avian influenza viruses isolated from migratory birds in central China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1):62. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0064-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Than T.T., Jo E., Todt D., Nguyen P.H., Steinmann J., Steinmann E. High environmental stability of hepatitis B virus and inactivation requirements for chemical biocides. J Infect Dis. 2019;219(7):1044–1048. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Aggarwal R., Naik S.R. Hepatitis E: intrafamilial transmission versus waterborne spread. J Hepatol. 1994;21(5):718–723. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(94)80229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sailaja B., Murhekar M.V., Hutin Y.J., Kuruva S., Murthy S.P., Reddy K.S.J. Outbreak of waterborne hepatitis E in Hyderabad, India, 2005. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(2):234–240. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tripathy A.S., Sharma M., Deoshatwar A.R., Babar P., Bharadwaj R., Bharti O.K. Study of a hepatitis E virus outbreak involving drinking water and sewage contamination in Shimla, India, 2015–2016. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(12):789–796. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lenglet A., Ehlkes L., Taylor D., Fesselet J.F., Nassariman J.N., Ahamat A. Does community-wide water chlorination reduce hepatitis E virus infections during an outbreak? A geospatial analysis of data from an outbreak in Am Timan, Chad (2016–2017) J Water Health. 2020;18(4):556–565. doi: 10.2166/wh.2020.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sarguna P., Rao A., Sudha Ramana K.N. Outbreak of acute viral hepatitis due to hepatitis E virus in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25(4):378–382. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chen Y.J., Cao N.X., Xie R.H., Ding C.X., Chen E.F., Zhu H.P. Epidemiological investigation of a tap water-mediated hepatitis E virus genotype 4 outbreak in Zhejiang Province, China. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(16):3387–3399. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816001898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Guthmann J.P., Klovstad H., Boccia D., Hamid N., Pinoges L., Nizou J.Y. A large outbreak of hepatitis E among a displaced population in Darfur, Sudan, 2004: the role of water treatment methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(12):1685–1691. doi: 10.1086/504321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bryan J.P., Iqbal M., Tsarev S., Malik I.A., Duncan J.F., Ahmed A. Epidemic of hepatitis E in a military unit in Abbotrabad, Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67(6):662–668. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Clayson E.T., Vaughn D.W., Innis B.L., Shrestha M.P., Pandey R., Malla D.B. Association of hepatitis E virus with an outbreak of hepatitis at a military training camp in Nepal. J Med Virol. 1998;54(3):178–182. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199803)54:3<178::aid-jmv6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Migliorati G., Prencipe V., Ripani A., Di Francesco C., Casaccia C., Crudeli S. An outbreak of gastroenteritis in a holiday resort in Italy: epidemiological survey, implementation and application of preventive measures. Vet Ital. 2008;44(3):469–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Arvelo W., Sosa S.M., Juliao P., López M.R., Estevéz A., López B. Norovirus outbreak of probable waterborne transmission with high attack rate in a Guatemalan resort. J Clin Virol. 2012;55(1):8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Borchardt M.A., Bradbury K.R., Alexander E.C., Jr, Kolberg R.J., Alexander S.C., Archer J.R. Norovirus outbreak caused by a new septic system in a dolomite aquifer. Ground Water. 2011;49(1):85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6584.2010.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Breitenmoser A., Fretz R., Schmid J., Besl A., Etter R. Outbreak of acute gastroenteritis due to a washwater-contaminated water supply, Switzerland, 2008. J Water Health. 2011;9(3):569–576. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Fernandes T.M.A., Schout C., De Roda Husman A.M., Eilander A., Vennema H., van Duynhoven Y.T.H.P. Gastroenteritis associated with accidental contamination of drinking water with partially treated water. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(5):818–826. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gunnarsdottir M.J., Gardarsson S.M., Andradottir H.O. Microbial contamination in groundwater supply in a cold climate and coarse soil: case study of norovirus outbreak at Lake Myvatn, Iceland. Hydrol Res. 2013;44(6):1114–1128. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hewitt J., Bell D., Simmons G.C., Rivera-Aban M., Wolf S., Greening G.E. Gastroenteritis outbreak caused by waterborne norovirus at a New Zealand ski resort. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(24):7853–7857. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00718-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mellou K., Sideroglou T., Potamiti-Komi M., Kokkinos P., Ziros P., Georgakopoulou T. Epidemiological investigation of two parallel gastroenteritis outbreaks in school settings. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):241. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nygård K., Vold L., Halvorsen E., Bringeland E., Røttingen J.A., Aavitsland P. Waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis in a religious summer camp in Norway, 2002. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(2):223–229. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803001894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Polkowska A., Räsänen S., Al-Hello H., Bojang M., Lyytikäinen O., Nuorti J.P. An outbreak of norovirus infections associated with recreational lake water in Western Finland, 2014. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(5):544–550. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Scarcella C., Carasi S., Cadoria F., Macchi L., Pavan A., Salamana M. An outbreak of viral gastroenteritis linked to municipal water supply, Lombardy, Italy, June 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14(29):15–17. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.29.19274-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.ter Waarbeek H.L.G., Dukers-Muijrers N.H.T.M., Vennema H., Hoebe C.J.P.A. Waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak at a scouting camp caused by two norovirus genogroups: GI and GII. J Clin Virol. 2010;47(3):268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tryfinopoulou K, Kyritsi M, Mellou K, Kolokythopoulou F, Mouchtouri VA, Potamiti-Komi M, et al. Norovirus waterborne outbreak in Chalkidiki, Greece, 2015: detection of GI.P2_GI.2 and GII.P16_GII.13 unusual strains. Epidemiol Infect 2019;147:e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 145.Werber D., Lausević D., Mugosa B., Vratnica Z., Ivanović-Nikolić L., Zizić L. Massive outbreak of viral gastroenteritis associated with consumption of municipal drinking water in a European capital city. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(12):1713–1720. doi: 10.1017/S095026880999015X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yang Z., Wu X., Li T., Li M., Zhong Y., Liu Y. Epidemiological survey and analysis on an outbreak of gastroenteritis due to water contamination. Biomed Environ Sci. 2011;24(3):275–283. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Outbreaks associated with untreated recreational water—California, Maine, and Minnesota, 2018–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(25):781–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 148.Pawlowski A. Suspected norovirus outbreak shuts down Colorado school district. [Internet]. New York: NBC News. 2019 Nov 21 [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.newsbreak.com/news/1462358518070/suspected-norovirus-outbreak-shuts-down-colorado-school-district. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ohwaki K., Nagashima H., Aoki M., Aoki H., Yano E. A foodborne norovirus outbreak at a hospital and an attached long-term care facility. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009;62(6):450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chen M.Y., Chen W.C., Chen P.C., Hsu S.W., Lo Y.C. An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis associated with asymptomatic food handlers in Kinmen. Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):372. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wang X., Yong W., Shi L., Qiao M., He M., Zhang H. An outbreak of multiple norovirus strains on a cruise ship in China, 2014. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;120(1):226–233. doi: 10.1111/jam.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Parashar U.D., Dow L., Fankhauser R.L., Humphrey C.D., Miller J., Ando T. An outbreak of viral gastroenteritis associated with consumption of sandwiches: implications for the control of transmission by food handlers. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;121(3):615–621. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhou X, Kong DG, Li J, Pang BB, Zhao Y, Zhou JB, et al. An outbreak of gastroenteritis associated with GII.17 norovirus-contaminated secondary water supply system in Wuhan, China, 2017. Food Environ Virol 2019;11(2):126–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 154.Zhang L., Li X., Wu R., Chen H., Liu J., Wang Z. A gastroenteritis outbreak associated with drinking water in a college in northwest China. J Water Health. 2018;16(4):508–515. doi: 10.2166/wh.2018.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Schmid D., Lederer I., Much P., Pichler A.M., Allerberger F. Outbreak of norovirus infection associated with contaminated flood water, Salzburg, 2005. Euro Surveill. 2005;10(6) doi: 10.2807/esw.10.24.02727-en. E050616.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Shang X., Fu X., Zhang P., Sheng M., Song J., He F. An outbreak of norovirus-associated acute gastroenteritis associated with contaminated barrelled water in many schools in Zhejiang, China. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sekwadi P.G., Ravhuhali K.G., Mosam A., Essel V., Ntshoe G.M., Shonhiwa A.M. Waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis on the KwaZulu–Natal Coast, South Africa, December 2016/January 2017. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(10):1318–1325. doi: 10.1017/S095026881800122X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Blanco A., Guix S., Fuster N., Fuentes C., Bartolomé R., Cornejo T. Norovirus in bottled water associated with gastroenteritis outbreak, Spain, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(9):1531–1534. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.161489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Xue C., Fu Y., Zhu W., Fei Y., Zhu L., Zhang H. An outbreak of acute norovirus gastroenteritis in a boarding school in Shanghai: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1092. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hoebe C.J.P.A., Vennema H., de Roda Husman A.M., van Duynhoven Y.T.H.P. Norovirus outbreak among primary schoolchildren who had played in a recreational water fountain. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(4):699–705. doi: 10.1086/381534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Vantarakis A., Mellou K., Spala G., Kokkinos P., Alamanos Y. A gastroenteritis outbreak caused by noroviruses in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(8):3468–3478. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Papadopoulos V.P., Vlachos O., Isidoriou E., Kasmeridis C., Pappa Z., Goutzouvelidis A. A gastroenteritis outbreak due to norovirus infection in Xanthi, Northern Greece: management and public health consequences. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15(1):27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Kim S.H., Cheon D.S., Kim J.H., Lee D.H., Jheong W.H., Heo Y.J. Outbreaks of gastroenteritis that occurred during school excursions in Korea were associated with several waterborne strains of norovirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4836–4839. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4836-4839.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Gaulin C., Nguon S., Leblanc M.A., Ramsay D., Roy S. Multiple outbreaks of gastroenteritis that were associated with 16 funerals and a unique caterer and spanned 6 days, 2011, Québec. Canada. J Food Prot. 2013;76(9):1582–1589. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]