Abstract

With the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in the world, domestic spaces have become dramatically important in terms of controlling pandemics and as an environment that must meet the needs of residents during the quarantine period. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the health parameters in the domestic space in the apartment type after COVID-19. The indicators related to physical health, mental health, and socio-economic lifestyle changes affecting the interior architecture of apartment houses have been evaluated with the use of a questionnaire with 632 respondents in Tehran. These indicators have been measured with regard to space, building structure, mental comfort, self-sufficiency, and workplace. The data were analysed using Friedman, Mean, and ANOVA tests to prioritize indicators in the SPSS software. The results indicated that variables related to mental health such as natural light, view, acoustic, and open or semi-open space are of particular importance. Therefore, attention to mental health parameters should be considered by planners, builders, and architects in apartment design.

Keywords: Healthy home, Domestic space choice, Interior architecture, Mental health, Housing choice

Highlights

-

•

The relationship between interior design and healthy housing is explained.

-

•

Dimensions of a healthy home about COVID_19 are divided into three factors of health and five indexes of home design.

-

•

The important factors of a healthy home about COVID_19 pandemic are identified to be considered in the future designs.

1. Introduction

In the last two decades, the world has witnessed the appearance and spread of a generation of viruses endangering the global health. They began with SARS-CoV in China and then, were spread to many Southeast Asian countries, North America, Europe, and Africa. Nine years later, a new coronavirus was recognized in the Middle East known as MERS-CoV, through which patients were involved with acute respiratory illness [1]. In late 2019, an unknown disease in China was reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), which was originally called nCoV-2019 (new coronavirus-2019). Then, it was officially renamed COVID_19 by WHO in 2020 [2].

COVID-19 quickly became one of the world's crises of the century. Until August 14, 2020, WHO database confirmed 20,730,456 cases of coronavirus globally with 751,154 reported deaths [3]. Due to high prevalence, high mortality rate, and the consequences that home quarantines have created for countries, it seems that having a healthy living environment is one of the main concerns of the people from several aspects. 1) Due to the high transmission of the virus, the home environment characteristics must have the necessary capabilities to survive the infection and prevent its spread. 2) Due to its high prevalence and the lack of capacity in hospitals, many patients who are not in the acute stage should be cared for at home. Hence, the houses must have the potential to become an isolated environment for infectious patients. 3) This disease has led to home quarantine in many countries creating psychological and social challenges as a result of long-term stay at home. Therefore, the house interior spaces must have the necessary capabilities to go through the period of these pandemics. All of these factors have led to paying more attention to a healthy home in the future both from the point of view of planners, designers, and policymakers and the people. These will undoubtedly have an impact on housing marketing.

The World Health Organization has drawn up some guidelines for healthy homes in European countries [4]. Some studies illustrate hygiene effects arising from housing progress and energy efficiency actions in developed countries [[5], [6], [7]]. Moreover, there are different healthy home certificates such as Inter NAchI, Healthy Home Evaluator (HHE) in USA, healthy home standards in New Zealand, and other certificates such as LEED and BREEAM which reveal that developed countries pay attention to the health of the residential building. Although a healthy home is a prerequisite for a healthy life [8], in Iran, as a developing country, the indicators of healthy housing have not been given much attention, and fewer studies have been carried out in this regard.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the preferences of the healthy and efficient home parameters from the residents' point of view, considering the prevalence of COVID_19 disease. The present study was performed in Tehran as one of the largest cities in Iran with the highest incidence of the disease. The importance of this is that identifying resident priorities can provide better solutions and improve housing development programs to increase home quality. Since the highest presence time during the quarantine period has been inside the house, the survey of residents has much concentrated on interior architecture in this study.

1.1. Healthy Housing

There is a growing concern for the link between housing and health among housing managers, public health physicians, and medical sociologists. Attention to health in architecture can be seen in the early twentieth century. With the modern medicine development, factors such as light, air, water, ventilation, and access to free space became the basis for the building design, particularly houses [9]. In this regard, different paradigms have emerged in the housing health field over time. Until the 1920s, the focus was on sanitation and the sewage system. Afterwards, until about 1970, the bacteria issue was raised. Since the 1990s, the risk of traditional hazards has shifted to new hazards, such as polluted air inside private houses known as Tight Building Syndrome (TBS).

Due to the home isolation to reduce energy consumption, this syndrome has been considered more because it has caused respiratory and allergic diseases [10]. Today, the home health issue is one of the most critical issues in various countries and many annual conferences and research are conducted in this field. However, measuring the direct housing quality impact on health was a difficult task in the past, and this challenge still accompanies us [11]. As stated, ‘Housing and health are not and will never be an exact science’ [12]. In recent decades, two building-related categories of health outcomes have been proposed based on the causality of the various health effects observed. The first category is Building Related Illness (BRI), which is a disease caused by pollutants in a closed space. The second category is Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) or a condition in which people living in a building suffer from illness and boredom symptoms without any good reasons to do so [13].

Numerous studies have been conducted over the past decades on the living conditions' impact on the residents’ health [5,14]. These conditions can impact or cause lead exposure, asthma, allergies, unintentional injuries, development of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and other illnesses. Heating systems can cause serious injuries or death such as burns, suffocation with smoke inhalation, and carbon monoxide poisoning [15,16]. Studies have shown that in addition to hazardous construction materials, the fungal growth on some materials in the presence of humidity threatens the health of residents due to respiratory and allergic diseases [[17], [18], [19]]. Poisoning as a result of tobacco smokes, exposure to formaldehyde (gas) from furniture products [15,16,19], mould growth in energy-efficient buildings [20], and the relationship between CO2 levels and indoor air ventilation [[21], [22], [23], [24]] illustrate the indoor air quality can affect the health.

In addition to physical symptoms, studies have revealed that indoor environmental conditions affect residents’ emotional stress and sleeping hours [25,26]. Bonnefoy [27] mentioned that mental health and lifestyle alongside with materials, noise, temperature comfort, lighting, home safety, indoor air quality can be effective factors in healthy housing. Hasselaar [10] divided the healthy home parameters into five categories: air quality, acoustics, comfort, safety, and social quality. Regarding mental health, Kearns et al. [28] believed that any interference from external or stressful factors threatens home health, thereby reducing the mental and social home functions. Evans et al. [29] discussed the structure parameters, maintenance, cooling and heating, layout type, noise, indoor air quality, and light. WHO LARES has reported on the prevalence of mental health symptoms in relation to housing problems due to low daylight, poor building view, noise, and insufficient privacy [30].

In addition to health and home research, there are several healthy housing assessment protocols such as Hazard Assessment and Reduction Program (Hazard Assessment and Reduction Program), American Healthy Homes Survey (AHHS), Community Environmental Health Resource Center (CEHRC) and Housing Quality Standards (HQS) which assess electrical hazards, structural hazards, moisture/mould hazards, presence of pests, ventilation, injury hazards, fire, and miscellaneous. Although Jacobs [28] pointed out that these protocols need to be standardized and validated. Health and Safety Rating System (HH&SRS) in England and healthy home standards in New Zealand focus on heating, insulation, ventilation, moisture, and drainage. Keall et al. [31] explained these approaches need to consider local factors such as climate, geography, culture, predominating building practices, important housing-related health issues, and existing building codes. The World Health Organization (WHO) has also set guidelines for a healthy home called HHGL (WHO Housing and health guidelines), which includes protection against infectious diseases, injuries, poisonings, psychological and social stress reduction, living environment improvement, informing of the housing use, and protection against the endangered population [4]. The first and second cases can be placed in the physical health field. The third case is related to mental health indicators. The fourth case refers to improving the living environment, in which the Coronavirus crisis has led to changes in the individuals living environment and lifestyle.

Recent studies in the field of healthy homes have focused on smart ventilation systems [32], filtration technology, Trombe walls, and biofiltration systems [33] such as active living wall (ALW) and green buildings [34]. Andargie et al. [35] in a review study have identified the type of house, floor level, and windows as the most important factors of thermal, visual, and acoustic comfort. In a review study by Barros et al. [36], these factors were effective parameters in mental health. In a general summary of health and home, according to Ormandy [30], it may be argued that health-threatening causes are usually one or a combination of three factors: residents' performance, home conditions, and objects.

1.2. Residents' preferences

People always seek the most suitable home for choosing, buying, or renting. So, residential preferences are significant to designers, planners, and sociologists. Preferences point to a wide range of inclinations and desires to meet the basic and transcendent human needs. In other words, residential preferences reflect both the mental and ideal individual images and what can actually happen. Therefore, it is the preferences that guide an individual's goals in choosing a home [37]. Housing preferences research has been developing for decades. Some has examined the role of sociocultural and demographic characteristics in different societies on the individual preference criteria [38,39]. Hooimeijer [40] stated that household priorities change through changes in individual's life and housing marketing. Sirgy et al. [41] considered the home symbolic aspects as useful in addition to the functional aspects and considered the choice to be due to a combination of social and psychological factors. Jansen et al. [37] divided residential preferences and techniques into the following nine categories: Traditional Housing Demand Research, The Decision Plan Nets Method, The Meaning Structure Method, The Multi-Attribute Utility Method, Conjoint Analysis, The Residential Images Method, Lifestyle Method, Neo-classical Economic Analysis, and Longitudinal Analysis.

In terms of people's preferences in choosing healthy housing, a study in Hong Kong was conducted on how much people spend on healthy homes following the outbreak of the SARS virus using the contingent valuation method. The study results based on the orientation parameters, vision and perspective, height, terrace, space dimensions, and ventilation indicated the general preference for healthy buildings [42]. Identifying the Canadian families' preferences for a healthy home based on the air quality parameters, light, and acoustics, is another study that has been done on healthy home preferences [43]. Also, a study in the United Kingdom compared the housing builders' preferences by the soft feature's viewpoint of a healthy home. The results showed that indoor living standards are the most critical priority for all groups compared to other parameters that are the neighbourhood, access to services, green space, and exterior building [44].

In summary, the preferential parameters of a healthy home in previous research are divided into three categories: comfort, structure and equipment, and space. Comfort parameters in lighting [43,[45], [46], [47]], view [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]], noise [42,43,[46], [47], [48]], and air quality [43,46,47] items have been considered. Technical conditions [45], heating and ventilation systems [43,[45], [46], [47]], insulation [43,45], and material [45] are parameters of structure and equipment. Space size [42,[45], [46], [47]], privacy [46,47], private outdoor or balcony [42,44,47], spatial organization [46,47], green space [44,47], and adaptability [44] have been investigated as space parameters. All parameters mentioned above may be of different importance among various cultural and economic contexts [49]. Previous studies have shown preferential differences in noise among apartment dwellers in five countries that are Japan, Germany, the United States, China, and Turkey [50]. The visual factors of the demanded indoor environment have been distinct between the Americans and the Chinese [51]. It has been observed that there are significant differences in housing preferences across European countries [52]. Therefore, preferences for healthy housing in each country due to social, cultural, and economic conditions can have different results, which shows the importance of this research. What is more, little research has been done on the preferences of residents in the crisis caused by pandemic diseases, which shows the need to address this issue.

1.3. Healthy interior space indicators related to COVID-19

To understand how the Coronavirus crisis affects people's future preferences in domestic space, we must first identify the factors that influence the interior design of homes and the problems they pose to residents. To this end, we have extracted points related to the interior from the WHO report on the COVID-19 virus. For example, the preliminary data on the COVID-19 virus show that according to the WHO report it may remain on the surface for hours or days. This may vary under different conditions such as surface type, temperature, or ambient humidity [53,54]. Therefore, the materials of finishing surfaces such as floors and walls as well as equipment surfaces such as valves and fittings are essential in preventing and intercepting the spread of the virus. Also, according to institutional technical committee for the promotion and prevention of COVID-19 advice about entering the house, the following items can be taken into account in home design:

-

•

When you return home, try not to touch anything. Keep a flat tray at the entrance to the house, containing the disinfectant solution

-

•

Take your shoes off immediately before entering the house.

-

•

Avoid physical contact with your family members until you have bathed or washed [55].

In the first Item, a smart home can be the perfect solution. The second case requires an entryway at home. The latter also indicates the need for bathrooms and toilets to be close to the entrance.

In addition to preventing the virus from entering the home, there are guidelines for patients who are being treated at home. The following are some of the home care instructions for patients:

-

•

Place the patient in a well-ventilated single room

-

•

Limit the movement of the patient in the house and minimize shared space.

-

•

Ensure that shared spaces (e.g., kitchen, bathroom) are well ventilated (keep windows open).

-

•

Household members should stay in a different room

-

•

Daily clean and disinfect surfaces [56].

Therefore, proper ventilation [57], materials, isolated and independent spaces, smart systems to reduce hand contact are the factors that can be used for home space during treatment.

According to the tips on home prevention and care, the components of interior architecture that are in the field of physical health can be categorized into two dimensions of space and structure of the house. Space-related dimensions include spatial organization, size and number of spaces, and the flexibility of spaces. The type of materials and features associated with installation are also structural components of the home.

Coronavirus is a serious challenge and significant public health problem, which can cause different stressors [58]. The prevalence of the disease [59] and the feeling of loneliness during home quarantine [60] is a stressful phenomenon. Stress can lead to mental health problems and depression [61]. Moreover, during infectious diseases, people's emotional reactions have a substantial effect on disease spread. Mental health weakness and increasing anxiety can endanger health measures [62,63]. Multiple studies on the Psychoneuroimmunology field have also shown there is a relationship between mental health and immune system responses and body protection against pathogens [64,65]. So it is necessary to have social resilience strategies in any society to decrease the burden of disease and its consequences during the epidemic crisis. Research on the effects of multi-day quarantine until several weeks has shown that it will have long-lasting consequences in the future [66]. Therefore, issues related to mental health at home are not limited to the quarantine period and may be considered in the choice of future homes.

In research in the field of mental health and housing, view [[67], [68], [69], [70]], noise [47,69,71,72], and natural light [47,69,70] have been studied as mental health parameters of the houses. Outdoor spaces have also been studied as mental health parameters, including terraces and balconies on a smaller scale. Open and semi-open spaces reduce stress on account of the increased social interactions [73,74] and reduce mental fatigue as a result of the breadth of vision and observation of nature [68,75]. Wågø et al. [76] also noted that terraces can be used as a living room and residents were delighted to be able to see the outdoors. View, acoustic, natural light, and the need for open and semi-open spaces are included in the conceptual framework of this study.

As stated in the WHO Housing and health guidelines (HHGL), in addition to maintaining the physical and mental health of residents, the home must also meet the socio-economic and functional needs of residents to improve their living environment [4]. As one of the consequences of the Corona Crisis has been the economic downturn in countries [77], the discussion of energy saving and the reduction of living costs in homes has also become paramount. From this perspective, homes that are self-sufficient in food or energy production, or low-energy homes can play an integral role in the family economy during this time. Therefore, the self-sufficiency factor has been considered in this study. Other changes made after the disease include the spread of virtual training in education and telecommuting for employees. Therefore, forecasting workspaces, location, privacy, a visual connection of this space, and flexibility of the house are some of the things that can be considered in the home space.

According to what was mentioned above, the classification of criteria related to the interior of the house, which was the basis of the questions in this research, is shown in Fig. 1 . Dimensions of a healthy home environment to prevent diseases, home treatment, and home quarantine include factors related to physical health, mental health, and health-related to function and lifestyle. These dimensions can be evaluated in five categories of space and internal structure of the building, mental comfort, workspace, and economic self-sufficiency.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

2. Methodology

As mentioned earlier, the main purpose of this study was to investigate the residential preferences of individuals in the choice or renovation of a residential unit in Tehran after the release of the COVID-19. Since nearly 80% of Tehran's population live in apartments, apartment households have been targeted. The purpose of the residential unit in this research is the interior of the house. This study separately and explicitly has measured respondents' evaluations of different attributes and the relative importance weight of each attribute (direct measurement) based on people's responses to hypothetical dwellings. The research was carried out in the form of a questionnaire, considering the advantages of this technique in collecting opinions/attitudes towards products or services, especially when the research involved a large sample size. The questionnaire is also cost-effective and familiar to most people. The experimental questionnaire consisted of 31 questions in two sections: demographic data and housing preferences. The housing preference questions were compiled and elaborated from the conceptual framework of the research that was presented in the previous section (Fig. 1) in 25 items and five Indexes space, structure, psychological, workplace, and self-sufficiency. Based housing preferences level were asked on the 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (4 = very high, 3 = high, 2 = low, and 1 = very low).

The data were collected over a two-week period in April 2020. Using a simple random sampling method, a minimum sample of 385 was sufficient according to the Cochran's formula. Due to the unknown participation rate, an online questionnaire was sent to a random sample of 2000 households living in apartments in Tehran, of which 632 valid answers were received with a response rate of 32%. The average time to complete the questionnaire met the expected 14 min. Cronbach's alpha from the questionnaire is 0.877, so the reliability of the questionnaire is at a good level.

Data from the questionnaire were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 for Windows. In order to prioritize the available indicators and dimensions, Friedman and the mean test were used. The ANOVA test was also used to investigate the differences in income variables. Prior to using these tests, the normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The results depicted that the test was significant and nonparametric tests could be used as a result.

3. Result

3.1. Sample characteristics

Table 1 describes the general characteristics of subject households. There was a relative balance between the gender of the respondents who were 54%female and 46% male. The average age of the respondents was 35 years of age. Most of the respondents were married and had children. In terms of education, the majority of them had the degree of bachelor and Master (40%–41%) and also were employed (74.4%). The relative distribution among respondents with income ranges was 20–50 million Rials (the currency of Iran). Among the economic deciles of Iran, this group belongs to the middle class of society (deciles 4–7).

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents.

| Gender (n = 632) | n | % | Marital Status (n = 632) | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 291 | 46 | Single | 229 | 36 |

| Female | 341 | 54 | Couple | 132 | 21 |

| Married with children | 271 | 43 | |||

| Age (n = 632) | n | % | Employment Status (n = 632) | n | % |

| 35 and below | 404 | 63.9 | Employed | 470 | 74.4 |

| 36–50 | 185 | 29.3 | Housewife | 53 | 8.4 |

| 51 and above | 43 | 6.8 | student | 86 | 13.6 |

| Retired | 23 | 3.6 | |||

| Monthly income (in Iranian Rial) | n | % | Education status (n = 632) | n | % |

| 20.000.000 and less | 51 | 8.1 | High school and below | 10 | 1.6 |

| 20.000.001–30.500.000 | 197 | 31.2 | Associate degree | 61 | 9.7 |

| 30.500.001–50.000.000 | 221 | 35 | Bachelor's degree | 261 | 41.3 |

| 50.000.001–100.000.000 | 136 | 21.5 | Postgraduate degree | 300 | 47.5 |

| 100.000.001 or above | 27 | 4.3 |

3.2. Identifying the preferences

As mentioned in the methodology section, 25 indicators were used to examine the interior of houses for three dimensions of mental health, physical health, and socio-economic lifestyle. Friedman test was used to evaluate the indicators to prioritize individuals. There was a statistically significant difference in preferences of domestic space, df = 24, p < 0.001, chi-square: 3525.445.

Table 2 shows the mean of the indicators in order of priority. Ranking of priorities shows that natural light, view to the open space, and acoustic achieved the highest average, which are the indicators related to mental health. The lowest average belonged to the indicator of closing or possibility of closing the kitchen, indicators related to the flexibility and location of services, which is mostly in the field of the home design related to physical health.

Table 2.

Friedman test results for healthy home Preferences.

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural lighting | 3.67 | .55 | 18.02 |

| View | 3.62 | .57 | 17.51 |

| Window facing open space | 3.59 | .57 | 17.18 |

| Acoustic | 3.56 | .63 | 16.93 |

| Kitchen ventilation | 3.55 | .55 | 16.85 |

| Natural ventilation | 3.49 | .59 | 16.28 |

| Having a terrace | 3.44 | .69 | 15.98 |

| Toilet ventilation | 3.27 | .77 | 14.49 |

| Low energy consumption | 3.27 | .72 | 14.38 |

| Terrace size | 3.22 | .76 | 13.87 |

| Floor/Wall material | 3.07 | .80 | 12.71 |

| Entrance size | 3.03 | .75 | 12.20 |

| Equipment material | 3.00 | .82 | 12.03 |

| Touchless faucet | 2.98 | .90 | 11.99 |

| Entrance space | 2.97 | .87 | 11.93 |

| Indoor gardens for organic food | 2.97 | .91 | 11.92 |

| Smart home | 2.94 | .93 | 11.88 |

| Bathroom place | 2.95 | .82 | 11.78 |

| Number of bathroom/toilet | 2.95 | .81 | 11.65 |

| Workplace as separated room | 2.84 | .84 | 10.80 |

| Toilet near/in rooms | 2.81 | .86 | 10.50 |

| Flexibility | 2.80 | .84 | 10.36 |

| Workplace openness | 2.69 | .86 | 9.65 |

| Kitchen flexibility | 2.39 | .83 | 7.48 |

| Closed kitchen | 2.22 | .91 | 6.63 |

In Table 3 , the first column is dimensions and the second one is the index. The third column is the indicators respectively, and the last one is the mean of the importance for each index. As it is clear from the table, mental comfort reached the highest rank and then followed by structure, self-sufficiency, space design, and workspace index, respectively.

Table 3.

The importance of healthy home dimensions.

| Index | Indicators | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | Space | Terrace, Size of space, Entrance, restrooms place, Number of toilet/bathroom, Kitchen flexibility | 2.87 |

| Structure | Ventilation, Material, Touchless faucet, Smart home | 3.18 | |

| Mental Health | Mental comfort | Natural lighting, View, Acoustic, Open space(Terrace) | 3.57 |

| Socio-economic Lifestyle | Workplace | Workplace, separated room, Flexibility, Openness | 2.77 |

| Self-Sufficiency | Low energy consumption, Food organic produce | 3.12 |

To determine the priorities of housing selection in each dimension, in the field of physical health and space, the highest priority was given to the presence of the terrace and its design and then the size of space, entrance, location and number of services, and kitchens flexibility. Ventilation is also the highest priority in factors related to indoor structure, followed by walls and floor materials, and building equipment. The least important in this category are contactless valves and smart homes. Mental health, which has been the most vital priority for residents, includes the parameters of natural light, vision, and the appropriate view to the open space, and then the acoustic of the space. In relation to the socio-economic lifestyle of the residents, the reduction of energy consumption is in the highest priority. The indicator of organic production with domestic gardens has been the next to be considered by the residents.

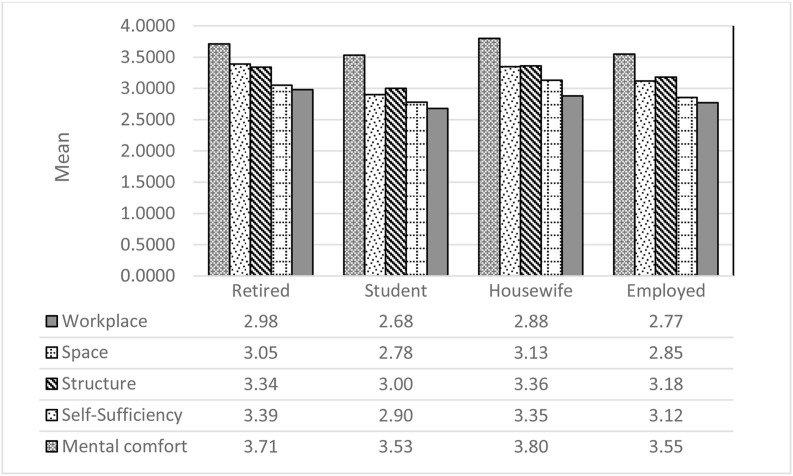

Since the discussion of telecommuting and virtual education is more specific to employees and students, the importance of the dimensions of home choice based on the employment of residents was measured separately. The results showed that the importance of workspace-related indicators is not related to employment status, and work-related indicators were the lowest priority for residents among all groups of employees, students, housewives, and retirees (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the importance of healthy home dimensions between employment status.

As mentioned earlier, the respondents came from different income categories. Table 4 shows a comparison of responses on the importance of healthy home dimensions by income category. The order of priorities between income groups was almost the same. This shows that the sample had a uniform perspective on the importance of the indicators. Only in the highest income group, the order of priority of self-sufficiency and space design parameters was different from the other groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of the importance of healthy home dimensions between income groups.

| Income | Mental comfort | Structure | Self-Sufficiency | Space | Workplace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20million | 3.62 | 3.26 | 3.20 | 2.98 | 2.91 |

| 20–30.5 million | 3.54 | 3.18 | 3.19 | 2.89 | 2.82 |

| 30.5–50 million | 3.56 | 3.17 | 3.11 | 2.84 | 2.76 |

| 50-100million | 3.61 | 3.21 | 3.04 | 2.85 | 2.68 |

| >100million | 3.58 | 2.98 | 2.77 | 2.88 | 2.72 |

As shown in Table 5 , the sig value between groups in the self-sufficiency dimension is smaller than 0.05. So, in economic terms, there is a significant difference between the two income groups below 20 million and 20–50 million Rials with the income group above 100 million Rials. In other words, as can be seen in Table 6 the preferential parameters of the highest economic decile are different from the lower and middle decile of society. In the highest income group, as shown in Table 4, the space parameter is more important than economic issues and home self-sufficiency, which can be justified for the affluent section of society.

Table 5.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) summary table comparing self-sufficiency parameter between income groups.

| Sum of squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-sufficiency | Between Groups | 5.825 | 4 | 1.456 | 3.300 | .011 |

| Within Groups | 276.665 | 540 | .443 | |||

| Total | 282.490 | 631 |

Table 6.

Tukey HSD test for comparison of healthy home dimensions.

| Dependent Variable | (I) Income | (J) Income | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Self-Sufficiency | <20million | 20–30.5 million | 0.03732 | 0.10436 | 0.996 | −0.2482 | 0.3228 |

| 30.5–50 million | 0.11991 | 0.10319 | 0.773 | −0.1624 | 0.4022 | ||

| 50-100million | 0.19118 | 0.10907 | 0.402 | −0.1072 | 0.4896 | ||

| >100million | .45752* | 0.15810 | 0.032 | 0.0250 | 0.8900 | ||

| 20–30.5 million | <20million | −0.03732 | 0.10436 | 0.996 | −0.3228 | 0.2482 | |

| 30.5–50 million | 0.08258 | 0.06509 | 0.711 | −0.0955 | 0.2606 | ||

| 50-100million | 0.15385 | 0.07406 | 0.231 | −0.0487 | 0.3565 | ||

| >100million | .42019* | 0.13632 | 0.018 | 0.0473 | 0.7931 | ||

| 30.5–50 million | <20million | −0.11991 | 0.10319 | 0.773 | −0.4022 | 0.1624 | |

| 20–30.5 million | −0.08258 | 0.06509 | 0.711 | −0.2606 | 0.0955 | ||

| 50-100million | 0.07127 | 0.07240 | 0.862 | −0.1268 | 0.2693 | ||

| >100million | 0.33761 | 0.13542 | 0.093 | −0.0329 | 0.7081 | ||

| 50-100million | <20million | −0.19118 | 0.10907 | 0.402 | −0.4896 | 0.1072 | |

| 20–30.5 million | −0.15385 | 0.07406 | 0.231 | −0.3565 | 0.0487 | ||

| 30.5–50 million | −0.07127 | 0.07240 | 0.862 | −0.2693 | 0.1268 | ||

| >100million | 0.26634 | 0.13995 | 0.317 | −0.1165 | 0.6492 | ||

| >100million | <20million | -.45752* | 0.15810 | 0.032 | −0.8900 | −0.0250 | |

| 20–30.5 million | -.42019* | 0.13632 | 0.018 | −0.7931 | −0.0473 | ||

| 30.5–50 million | −0.33761 | 0.13542 | 0.093 | −0.7081 | 0.0329 | ||

| 50-100million | −0.26634 | 0.13995 | 0.317 | −0.6492 | 0.1165 | ||

*. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

4. Discussion

These results support the findings of Gou et al. [78] that natural light was the most preferred criterion among healthy home factors. According to the studies conducted by Prochorskaite et al. [44] in the UK and Chan et al. [42] in Hong Kong, visual quality was the most significant criterion for residents and was consistent with the findings of this study. As mentioned by Wong et al. [79], the noise has been the most important problem in the interior quality of Hong Kong apartments that this parameter should be considered when designing a healthy home. In this study, the acoustic quality of space to prevent noise was the third rank in residents’ preferences, which shows the importance of this parameter. However, air quality was the most significant priority for a healthy indoor environment in most previous studies [[45], [46], [47]]. Because airflow is the most important source of coronavirus transmission, air quality seemed to be a top priority for residents. However, the results of this study illustrated that long-term quarantine and staying home were more important to residents than physical illness. The findings highlighted that qualitative parameters related to wellbeing are more important than hygienic parameters.

The results of ANOVA and mean tests showed that the individual employment status did not affect the parameters priority related to the workplace. Among the income groups, only the highest-income groups had different responses in terms of prioritizing issues related to the household economy. This shows that the low priorities associated with the housing economy can be justified with the low financial importance concerns for them. However, the most important priority of all income groups was to pay attention to the health mental parameters at home.

The importance of mental health has been emphasized in the form of a number of resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly and the World Health Assembly [80]. Although most of these factors are seen in the indoor quality section of evaluation systems such as LEED, BREEAM, and other systems, these standards are mostly quantitative and are far away from the qualitative nature of mental health. These parameters can also become mandatory or incentive requirements in rating systems to increase the quality of the home, especially in the face of crises such as COVID-19.

As mentioned in the literature review, the prevalence of the disease, and the feeling of loneliness in quarantine can cause various stressors. Research has shown that stress can increase the vulnerability of the immune system to diseases [81]. Therefore, one of the ways to fight pandemic diseases such as coronavirus is preventive actions in architectural design to increase mental health and reduce stress. According to the research results, some suggestions on architectural design can be presented as follows:

-

•

The use of large windows with higher percentages than what is determined by the national regulations of Iran is one of the design solutions due to the wide view and the increase in lighting of the space especially in the public spaces of home, provided that energy dissipation is reduced by considering new technologies.

-

•

Apartment light-wells, which are very common in Iran, receive the least amount of light according to standards. They also face problems in terms of ventilation and sound transmission. Therefore, there is a need to reconsider the use of light-wells or improve their quality in residential building for wellbeing.

-

•

Building orientation to receive sufficient light and the suitable landscape is another criterion for increasing the indoor quality, especially the use of South and East lighting according to the climate of Iran.

-

•

Plants are beneficial because of their calming effect on stress reduction and their effect on improving air quality, reducing noise, and creating proper vision. Thus, vertical gardens and living walls can thrive in indoor spaces or in the balcony. However, we need a solution to reduce its costs for wider use, especially in developing countries.

-

•

The need to determine the appropriate per capita and depth of private open or semi-open spaces in accordance with the socio-cultural context of each region will be the other effective strategies to promote the mental health of residents.

-

•

The use of sound insulation materials in interior and exterior walls in the comfort zone can increase residents' satisfaction.

One of the differences between the results of this study compared to other studies was the low importance of energy consumption criterion among respondents. Spetic et al. [43] reported that energy efficiency was a top priority for Canadians who were willing to pay to improve it. The justification is that in Iran, on account of the abundant sources of fossil fuels and its cheap price, the culture of using energy has been focused on consumption instead of saving. So, in Iran, household energy consumption is three times higher than the world average. Cheap energy is not a license to waste national capital, so planners, policymakers, and designers must consider the parameter of optimizing energy consumption, especially in residential buildings.

5. Conclusion

There is a lot of research about healthy homes and their parameters over time. However, despite the chronic and new infectious diseases’ emergence such as coronaviruses in recent decades, there is little related research regarding the domestic space field. Because of the COVID-19 being widespread and global and the number of people infected with the disease and its mortality, social distance in countries and home quarantine has increased and the attention paid to such diseases, and their impact on home space have also increased. So, the link between home and health can be more prominent in the future.

This study aimed to find the people's preferences and priorities to choose healthy homes after the COVID-19 crisis among apartment residents in Tehran as one of the most infected cities by this disease. Although it should be noted that all healthy home parameters should be considered in the interior space design and implementation, knowing the housing priorities and preferences will provide better solutions and improve housing development programs to increase the housing quality. In this study, after extracting the indicators related to healthy housing in the disease encounter from reputable global sources and authorities, three physical health, mental health, and lifestyle-based health parameters were selected as the research criteria. These criteria were categorized into five indexes: space, structure, mental comfort, self-sufficiency, and workspace.

The findings revealed that the most critical priorities for residents were natural light, visibility, the acoustics of the interior space, and the open or semi-open space (terrace). The house design and workspace were the least important criteria. Overall, the mental health parameter has been the most important priority for residents in all income groups, indicating the home importance to go through the quarantine period and prevent the psychological damage caused by staying at home. The dimensions related to physical health and lifestyle-based (socio-economic) health were with the same importance.

Rated as the preferred attributes in the home, materials promoting better insulation, size, and orientation of windows promoting natural light and view quality, balcony with more depth, and indoor living walls, maybe well-positioned when targeted to Iranian households. These proposals can also raise the tolerance threshold of citizens to coexist with COVID-19.

Since this study only evaluated the interior design parameters, it is suggested that other housing scales, such as the building structure and the neighbourhood, be considered in the future. Due to the respondents' demographic characteristics, who were mainly under 50 and the middle class, it is recommended to use more comprehensive statistical samples. Also, research replication in different areas and re-testing this survey can provide higher confidence responses after the disease subsides and communities return to normal conditions. In order to examine the healthy housing indicators, people's importance in terms of health experts and economic potentiality should be measured as well as the importance of the indicators in terms of themselves, which can be traced in future research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mahsa Zarrabi: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. Seyed-Abbas Yazdanfar: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Seyed-Bagher Hosseini: Supervision, All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Jahangir M.A., Muheem A., Rizvi M.F. Coronavirus (COVID-19): history, current knowledge and pipeline medications. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020;4:140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guarner J. Three emerging coronaviruses in two decades. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020;153:420–421. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/table (n.d.) accessed.

- 4.W.H. Organization Guidelines for healthy housing. Health All Ser. 1988;31 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson H., Petticrew M., Morrison D. Health effects of housing improvement: systematic review of intervention studies. Bmj. 2001;323:187–190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson G., Barton A., Basham M., Foy C., Eick S.A., Somerville M. The Watcombe housing study: the short-term effect of improving housing conditions on the indoor environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;361:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson H., Petticrew M., Douglas M. Health impact assessment of housing improvements: incorporating research evidence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2003;57:11–16. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuluaga M.C., Guallar-Castillón P., Conthe P., Rodríguez-Pascual C., Graciani A., León-Muñoz L.M., Gutiérrez-Fisac J.L., Regidor E., Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Housing conditions and mortality in older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Am. Heart J. 2011;161:950–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehl J. sixth ed. Island press; 2011. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasselaar E. first ed. IOS Press; 2006. Health Performance of Housing: Indicators and Tools. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breysse P., Farr N., Galke W., Lanphear B., Morley R., Bergofsky L. The relationship between housing and health: children at risk. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:1583–1588. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranson R. first ed. Taylor & Francis; 2002. Healthy Housing: a Practical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Momani H.M., Ali H.H. Sick building syndrome in apartment buildings in Jordan, Jordan. J. Civ. Eng. 2008;2:391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnefoy X.R., Braubach M., Moissonnier B., Monolbaev K., Röbbel N. Housing and health in Europe: preliminary results of a pan-European study. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2003;93:1559–1563. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller-Thomson E., Hulchanski J.D., Hwang S. The housing/health relationship: what do we know? Rev. Environ. Health. 2000;15:109–134. doi: 10.1515/REVEH.2000.15.1-2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2004;25:397–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNamara S., Connell J. Homeward bound? Searching for home in inner Sydney's share houses. Aust. Geogr. 2007;38:71–91. doi: 10.1080/00049180601175873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulse K., McPherson A. Exploring dual housing tenure status as a household response to demographic, social and economic change. Hous. Stud. 2014;29:1028–1044. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2014.925097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matte T.D., Jacobs D.E. Housing and health—current issues and implications for research and programs. J. Urban Health. 2000;77:7–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02350959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonnefoy X., Braubach M., Krapavickaite D., Ormand D., Zurlyte I. Housing conditions and self-reported health status: a study in panel block buildings in three cities of Eastern Europe. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2003;18:329–352. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHO.0000005757.37088.a9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano-Jiménez A., Lizana J., Molina-Huelva M., Barrios-Padura Á. Indoor environmental quality in social housing with elderly occupants in Spain: measurement results and retrofit opportunities. J. Build. Eng. 2020;30:101264. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heracleous C., Michael A. Experimental assessment of the impact of natural ventilation on indoor air quality and thermal comfort conditions of educational buildings in the Eastern Mediterranean region during the heating period. J. Build. Eng. 2019;26:100917. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strengers Y., Maller C. Integrating health, housing and energy policies: social practices of cooling. Build. Res. Inf. 2011;39:154–168. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2011.562720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takaoka M., Suzuki K., Norbäck D. Current asthma, respiratory symptoms and airway infections among students in relation to the school and home environment in Japan. J. Asthma. 2017;54:652–661. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1255957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahrentzen S., Erickson J., Fonseca E. Thermal and health outcomes of energy efficiency retrofits of homes of older adults. Indoor Air. 2016;26:582–593. doi: 10.1111/ina.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennet I.E., O'Brien W. Field study of thermal comfort and occupant satisfaction in Canadian condominiums. Architect. Sci. Rev. 2017;60:27–39. doi: 10.1080/00038628.2016.1205179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnefoy X. Inadequate housing and health: an overview. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2007;30:411–429. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2007.014819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearns A., Hiscock R., Ellaway A., Macintyre S. “Beyond four walls”. The psycho-social benefits of home: evidence from west central Scotland. Hous. Stud. 2000;15:387–410. doi: 10.1080/02673030050009249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans G.W., Wells N.M., Moch A. Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J. Soc. Issues. 2003;59:475–500. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ormandy D. first ed. Routledge; 2009. Housing and Health in Europe: the WHO LARES Project. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keall M., Michael B., Howden-Chapman G.P., Cunningham M., Ormandy D. Assessing housing quality and its impact on health, safety and sustainability. Theory and Methods. 2010;64:765–771. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.100701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guyot G., Sherman M.H., Walker I.S. Smart ventilation energy and indoor air quality performance in residential buildings: a review. Energy Build. 2018;165:416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.12.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu G., Xiao M., Zhang X., Gal C., Chen X., Liu L., Pan S., Wu J., Tang L., Clements-Croome D. A review of air filtration technologies for sustainable and healthy building ventilation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017;32:375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2017.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balaban O., Puppim de Oliveira J.A. Sustainable buildings for healthier cities: assessing the co-benefits of green buildings in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;163:S68–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andargie M.S., Touchie M., O'Brien W. A review of factors affecting occupant comfort in multi-unit residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2019;160:106182. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barros P., Ng Fat L., Garcia L.M.T., Slovic A.D., Thomopoulos N., de Sá T.H., Morais P., Mindell J.S. Social consequences and mental health outcomes of living in high-rise residential buildings and the influence of planning, urban design and architectural decisions: a systematic review. Cities. 2019;93:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jansen S.J.T., Coolen H.C.C.H., Goetgeluk R.W., editors. The Measurement and Analysis of Housing Preference and Choice. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulliner E., Algrnas M. Preferences for housing attributes in Saudi Arabia: a comparison between consumers' and property practitioners' views. Cities. 2018;83:152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jansen S.J.T. Different values, different housing? Hous. Theor. Soc. 2013;31:254–276. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooimeijer P., Oskamp A. A simulation model of residential mobility and housing choice. Netherlands J. Hous. Built Environ. 1996;11:313–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02496594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirgy M.J., Grzeskowiak S., Su C. Explaining housing preference and choice: the role of self-congruity and functional congruity. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2005;20:329–347. doi: 10.1007/S10901-005-9020-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan E., Yiu C.Y., Baldwin A., Lee G. Value of buildings with design features for healthy living: a contingent valuation approach. Facilities. 2009;27:229–249. doi: 10.1108/02632770910944952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spetic W., Kozak R., Cohen D. Willingness to pay and preferences for healthy home attributes in Canada. For. Prod. J. 2005;55:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prochorskaite A., Couch C., Malys N., Maliene V. Housing stakeholder preferences for the “Soft” features of sustainable and healthy housing design in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2016;13:111. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palicki S. Housing preferences in various stages of the human life cycle, real estate manag. Valuation. 2020;28:91–99. doi: 10.2478/remav-2020-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee E. Indoor environmental quality (IEQ) of LEED-certified home: importance-performance analysis (IPA), Build. Environ. Times. 2019;149:571–581. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.12.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang N.N., Lee T.K., Kim J.T. Characteristics of the quality of Korean high-rise apartments using the health performance indicator. Indoor Built Environ. 2013;22:157–167. doi: 10.1177/1420326X12470344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wardman M., Bristow A.L. Traffic related noise and air quality valuations: evidence from stated preference residential choice models. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2004;9:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9209(03)00042-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zalejska-Jonsson A., Wilhelmsson M. Impact of perceived indoor environment quality on overall satisfaction in Swedish dwellings. Build. Environ. 2013;63:134–144. doi: 10.1016/J.BUILDENV.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Namba S., Kuwano S., Schick A., Aclar A., Florentine M., Da Rui Z. A cross-cultural study on noise problems: comparison of the results obtained in Japan, West Germany, the USA, China and Turkey. J. Sound Vib. 1991;151:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ham T.Y., Guerin D.A. A cross‐cultural comparison of preference for visual attributes in interior environments: America and China. J. Interior Des. 2004;30:37–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1668.2004.tb00398.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kersloot J., Kauko T. Measurement of housing preferences: a comparison of research activity in The Netherlands and Finland, Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2004;1:144–163. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Organization W.H. 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public: Myth Busters. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unah, Action Protocol Against Covid-19 Univ. Nac. AUTÓNOMA HONDURAS. 2020 https://www.unah.edu.hn/dmsdocument/9733-home-entrance-protocols-covid-19 accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Organization W.H. World Health Organization; 2020. Surface Sampling of Coronavirus Disease ( COVID-19): a Practical “How to” Protocol for Health Care and Public Health Professionals. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morawska L., Tang J.W., Bahnfleth W., Bluyssen P.M., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., Cao J., Dancer S., Floto A., Querol X. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ. Int. 2020;142:105832. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiang Y.-T., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Zhang Q., Cheung T., Ng C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J., Wu W., Zhao X., Zhang W. Recommended psychological crisis intervention response to the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China: a model of West China Hospital, Precis. Clin. Med. 2020;3:3–8. doi: 10.1093/pcmedi/pbaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dar K.A., Iqbal N., Mushtaq A. Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017;29:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rubin G.J., Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. Bmj. 2020;368:313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cullen W., Gulati G., Kelly B.D. Mental health in the Covid-19 pandemic. QJM An Int. J. Med. 2020;113:311–312. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson R.J., Kabat-Zinn J., Schumacher J., Rosenkranz M., Muller D., Santorelli S.F., Urbanowski F., Harrington A., Bonus K., Sheridan J.F. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom. Med. 2003;65:564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vasile C. Mental health and immunity. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020;20:211. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lunn P.D., Belton C.A., Lavin C., McGowan F.P., Timmons S., Robertson D.A. Using behavioral science to help fight the coronavirus. J. Behav. Public Adm. 2020;3:1–15. doi: 10.30636/jbpa.31.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Draganova V.Y., Matsumoto H., Tsuzuki K. AIP Conf. Proc. AIP Publishing LLC; 2017. Energy performance of building fabric–Comparing two types of vernacular residential houses; p. 160001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaplan R. The nature of the view from home: psychological benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001;33:507–542. doi: 10.1177/00139160121973115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee J., Je H., Byun J. Well-being index of super tall residential buildings in Korea. Build. Environ. 2011;46:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Veitch J.A., Christoffersen J., Galasiu A.D. Daylight and view through residential windows: effects on well-being, resid. Daylighting Well-Being. 2013:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jensen H.A.R., Rasmussen B., Ekholm O. Neighbour noise annoyance is associated with various mental and physical health symptoms: results from a nationwide study among individuals living in multi-storey housing. BMC Publ. Health. 2019;19:1508. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7893-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klompmaker J.O., Janssen N.A.H., Bloemsma L.D., Gehring U., Wijga A.H., van den Brink C., Lebret E., Brunekreef B., Hoek G. Residential surrounding green, air pollution, traffic noise and self-perceived general health. Environ. Res. 2019;179:108751. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swapan A.Y., Bay J.H., Marinova D. Importance of the residential front yard for social sustainability: comparing sense of community levels in semi-private-public open spaces. J. Green Build. 2019;14:177–202. doi: 10.3992/1943-4618.14.2.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marshall M. Designing balconies, roof terraces, and roof gardens for people with dementia. J. Care Serv. Manag. 2011;5:156–159. doi: 10.1179/175016811X13020827976762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Groenewegen P.P., van den Berg A.E., Maas J., Verheij R.A., de Vries S. Is a green residential environment better for health? If so, why? Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2012;102:996–1003. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.674899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wågø S., Hauge B., Støa E. Between indoor and outdoor: Norwegian perceptions of well-being in energy-efficient housing. J. Architect. Plann. Res. 2016:326–346. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fetzer T., Hensel L., Hermle J., Roth C. Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2020:1–36. doi: 10.1162/rest_a_00946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gou Z., Lau S.S.-Y., Zhang Z. A comparison of indoor environmental satisfaction between two green buildings and a conventional building in China. J. Green Build. 2012;7:89–104. doi: 10.3992/jgb.7.2.89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong S.-K., Lai L.W.-C., Ho D.C.-W., Chau K.-W., Lam C.L.-K., Ng C.H.-F. Sick building syndrome and perceived indoor environmental quality: a survey of apartment buildings in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2009;33:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Organization W.H. mental health; 2001. World Health Report 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Segerstrom S.C., Miller G.E. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]