The novel coronavirus1 has evolved into a global pandemic. Until now, there is limited knowledge about the cardiac involvement in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). We report a case of novel coronavirus pneumonia with associated acute myocardial injury2 confirmed by biomarkers and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

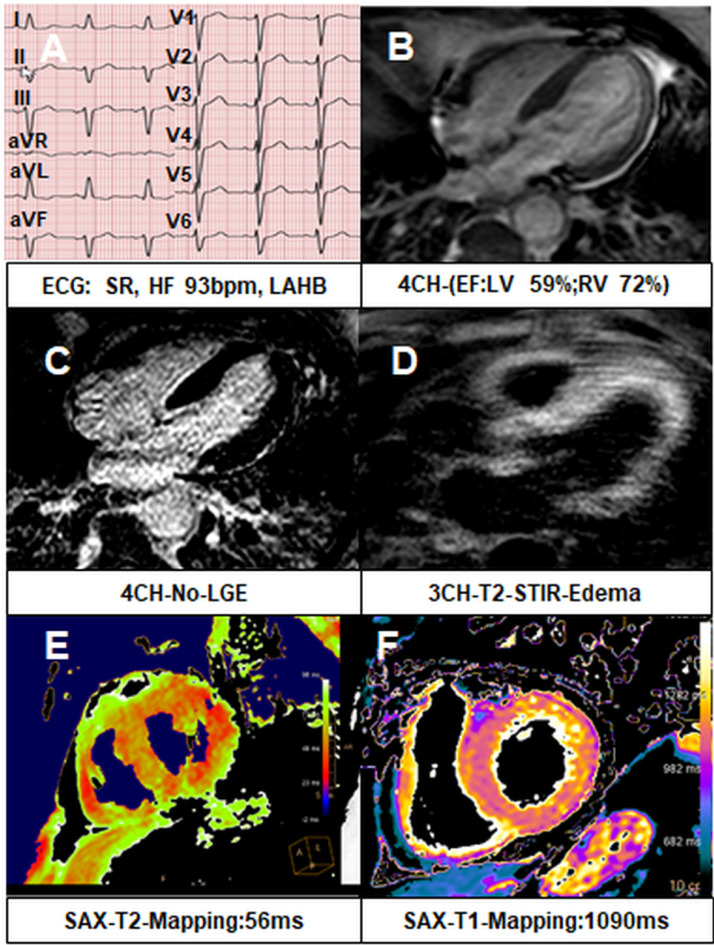

A 75-year-old man developed fever, chills, and a productive cough on March 19, 2020. His cardiovascular risk factors included hypertension, obesity, former smoking, and renal failure (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes-1). A severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 test was positive, and home quarantine was advised; however, worsening dyspnea required hospitalization. Besides cough, fever (38.7°C), and low oxygen saturation (88%, without oxygen), laboratory results revealed elevated C-reactive protein (82 mg/liter), elevated myoglobin (636 µg/liter), troponin T (high sensitive, 80 ng/liter), and N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (833 ng/liter). Electrocardiogram revealed left anterior fascicular block and T-wave inversion in lead aVL (Figure 1 a, 12-lead electrocardiogram). Screening tests for other viruses (Adenovirus; Coronaviridae 229E, HKU1, NL63, OC43; Human Bocavirus; Metapneumovirus; Rhinovirus/Enterovirus; Parainfluenza 1–4) were negative. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection was reconfirmed in the laboratory. Because troponin was rising (191 ng/liter), coronary angiography was performed on March 23, 2020, and epicardial stenosis was excluded, but left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic filling pressure was elevated at 14 mm Hg. Echocardiogram performed on the same day revealed normal LV and right ventricular function with signs of concentric LV remodeling and no regional wall motion abnormality. Cardiac MRI was performed on March 24, 2020 for evaluation of possible inflammatory myocardial injury. Because of dyspnea, the cardiac MRI (Philips 1.5 Tesla) examination was performed during free breathing using mostly single-shot sequences. Normal LV and right ventricular function and no regional wall motion abnormalities were noted (Figure 1b, Video 1–Cine single-shot 3-dimensional balanced turbo-field-echo sequence—4 chamber view). No focal fibrosis was detected in late gadolinium enhancement sequences (Figure 1c, single-shot inversion recovery sequence—4 chamber view). Global edema in T2 weighted images was visible (Figure 1d, T2 [short tau inversion recovery] sequence—3 chamber view) as well as globally elevated T2 (56 ms, referent 48 ± 3 ms) (Figure 1e, T2 mapping—short-axis view) and T1 (1,090 ms, referent 989 ± 28 ms) (Figure 1f, T1 mapping—short-axis view) mapping times, suggesting acute myocardial injury. On March 26, 2020, hypoxic respiratory failure (saturation of 80%) required mechanical ventilation. The patient improved and was extubated, and the level of cardiac biomarkers declined (N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide 631 ng/liter, troponin 61 ng/liter) in due course.

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI in COVID-19 (A) 12-lead electrocardiogram (B) Cine 4 chamber view (C) Late gadolinium enhancement 4 chamber view (D) T2 short tau inversion recovery 3 chamber view (E) T2 Mapping short axis view (F) T1 Mapping short axis view. CH, chamber; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; ECG, electrocardiogram; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; SAX, short axis; SR, sinus rhythm; STIR, short tau inversion recovery.

Cardiac MRI with its unique accuracy in defining cardiac morphology and function and its ability to provide tissue characterization makes it well suited to study cardiac involvement in COVID-19. Recently, Inciardi et al3 proved severe biventricular myocardial injury with edema and late gadolinium enhancement. In the absence of epicardial coronary artery stenosis, sub-clinical myocardial dysfunction in COVID-19 may be a consequence of an impairment of microcirculatory endothelial function observed during the early stages of the systemic inflammatory response to the infection, which portends a poor prognosis in patients with established cardiovascular disease and impaired microcirculatory endothelial function.4 In addition, direct COVID-19‒mediated infection of endothelial cells might contribute to cardiac injury.5

In summary, we show that elevated biomarkers of cardiac injury were associated with generalized myocardial edema without late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac MRI despite a normal echocardiogram during COVID-19.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2020.04.025.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China [e-pub ahead of print]. JAMA Cardiol 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950, accessed March 25, 2020 ;e200950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [e-pub ahead of print]. JAMA Cardiol 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096, accessed March 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mehra MR, Ruschitzka F. COVID-19 illness and heart failure: a missing link? JACC Heart Fail. 2020 June;8(6):512–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 May 2;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.