Abstract

Background and Objective

Infectious disease outbreaks pose psychological challenges to the general population, and especially to healthcare workers. Nurses who work with COVID-19 patients are particularly vulnerable to emotions such as fear and anxiety, due to fatigue, discomfort, and helplessness related to their high intensity work. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of a brief online form of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) in the prevention of stress, anxiety, and burnout in nurses involved in the treatment of COVID patients.

Methods

The study is a randomized controlled trial. It complies with the guidelines prescribed by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist. It was conducted in a COVID-19 department at a university hospital in Turkey. We recruited nurses who care for patients infected with COVID-19 and randomly allocated them into an intervention group (n = 35) and a no-treatment control group (n = 37). The intervention group received one guided online group EFT session.

Results

Reductions in stress (p < .001), anxiety (p < .001), and burnout (p < .001) reached high levels of statistical significance for the intervention group. The control group showed no statistically significant changes on these measures (p > .05).

Conclusions

A single online group EFT session reduced stress, anxiety, and burnout levels in nurses treating COVID-19.

Introduction

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO)1 China office shared information about some pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in Wuhan City. The WHO later named this outbreak the “Coronavirus disease 2019″ (COVID-19). The rapid global spread of the disease led to the declaration that COVID-19 was an epidemic on March 11, 2020.1 The first cases in Turkey were reported on that date, and 7428 cases had been identified in the country by April 29.2 With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers have assumed critical responsibilities in the control, prevention, care, and treatment of its spread. They provide necessary health interventions for possible or confirmed COVID-19 patients, working on the front lines and often for long hours and under harsh, fatiguing conditions. Infectious disease outbreaks have a negative psychological impact on the general population, and especially on health workers.3 , 4 Even the social distancing required to prevent outbreaks can cause social and psychological distress.

During this period, the pressure of family responsibilities comes into conflict with feelings of internal duty towards patients, increasing emotional stress and often contributing to burnout.5 In studies conducted following the 2003 SARS outbreak, high levels of stress and psychological distress were observed among healthcare workers. A lesson from these findings is that psychological problems not handled during a pandemic may lead to longstanding problems.6 Therefore, it is important for any health response strategy to protect the mental health of healthcare workers who are combating an epidemic.7 Studies of healthcare professionals who care for COVID-19 patients, primarily nurses, have reported symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and discomfort.3 , 4 , 7 , 8 Sun et al.9 found that nurses who care for COVID-19 patients experience negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety, due to fatigue, discomfort, and helplessness related to their high-intensity work. Numerous studies have recently appeared which suggest that special interventions should be applied to promote the mental well-being of healthcare professionals exposed to COVID-19 and to prevent burnout.3 , 4 , 7., 8., 9., 10. Failure to take these steps may not only create unnecessary mental health challenges for caregivers, they negatively affect patient care and safety and can also cause an increased risk of malpractice.11

Background

A promising innovation for addressing psychological distress is called The Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT).12 A surprising 98% of the efficacy studies investigating the approach show statistically significant improvements in the management of psychological distress.13 EFT has also been shown to be effective in addressing emotional challenges such as anxiety, depression, burnout, stress management, and fears.14., 15., 16.

The basic principle of EFT is to send activating and deactivating signals to the brain by stimulating points on the skin that have distinctive electrical properties, usually by tapping on them.14 These points correspond with the acupressure points that in Traditional Chinese Medicine are believed to regulate the flow of the body's energies. They are stimulated through tapping or other types of touch. Balancing and harmonizing the client's energies is believed to relax and optimize body, mind, and emotions.17 , 18 The research indicates that a broad spectrum of the population presenting with a wide range of issues respond to the approach.14., 15., 16. , 19., 20., 21. Church et al. found that self-administered EFT provided significant improvements in anxiety, depression, pain, and craving scores.12 A meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled EFT trials for anxiety disorders reported a large therapeutic effect for EFT (d = 1.23 (95% CI 0.82–1.64, P <0.001).22

Online psychological assistance services have been widely implemented during the COVID19 pandemic.3 The State Council of China set up psychological assistance helplines during the outbreak.3 , 23 Over the first three weeks of the epidemic in the United Kingdom, a digital learning package was developed for healthcare professionals, which included strategies for managing symptoms of fear, anxiety, and depression via psychological first aid and healthy lifestyle behaviors. This e-packet was widely accessed within a week of being posted, suggesting that healthcare providers found it a useful resource for supporting their psychological health during the COVID-19 outbreak.24 Such programs demonstrate that access to psychological using technology is valued by healthcare providers treating COVID-19. Reducing the psychological distress of nurses treating COVID-19 is an important requirement for managing the pandemic effectively.

Studies about COVID-19 are mostly related to prevention and treatment of the disease itself. A few have examined the psychological health challenges of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak. Although these studies propose a range of interventions methods for these psychological difficulties, no research evaluating their effectiveness have yet been conducted.

This study aims to investigate the efficacy of EFT in the prevention of stress, anxiety, and burnout in nurses who play an important role in the fight against COVID-19.

The three research hypotheses included:

Hypothesis 1

A single online group EFT session is effective in reducing nurses' stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypothesis 2

A single online group EFT session during the COVID-19 pandemic is effective in reducing nurses' anxiety levels.

Hypothesis 3

During the COVID-19 pandemic, A single online group EFT session is effective in reducing nurses' professional burnout levels.

Methods

Study design

A randomized controlled design was used. The study complied with guidelines outlined under the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Istanbul Medeniyet University Göztepe Education and Research Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Participants also read, approved, and signed a consent form after being told about the nature of the study. Once the study was completed, EFT was offered to anyone from the control group who wanted to participate.

Participants

This study was carried out in May 2020 with nurses caring for COVID-19 patients in a university hospital in Turkey. Inclusion criteria were: a) not having any psychiatric diagnoses, b) not taking any courses about coping with anxiety and stress, and c) volunteering to participate in the study.

Sample size and randomization

To determine the sample size, a power analysis was conducted using the GPower 3.1 program, and the estimated effect size was based on results of similar studies.25 , 26 The required sample size with an effect size of 0.5 and alpha level of 0.05 was determined to be 80. The power of the analysis with this sample size is 90.3%.

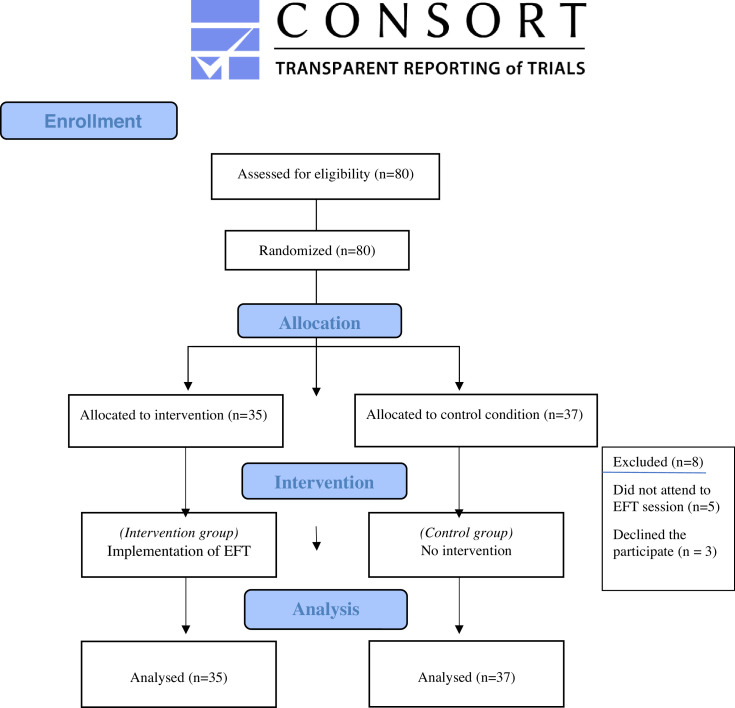

Nurses were selected as the focus of this study because of their primary role in the treatment of COVID-19 and their vulnerability to stress, anxiety, and burnout. Eighty nurses who met the inclusion criteria were assigned to groups using an online random number generator. The Clinical Trial Registration number was “NCT04393077.” Eight of the participants did not complete the study. The 72 nurses who did complete the study included 35 in the intervention group and 37 in the control group. Fig. 1 is a flow diagram showing the selection process.

Fig. 1.

Allocation of subjects according to the CONSORT 2010 flow diagram.

Measures

The data were collected with a Descriptive Characteristics Form, a subjective units of distress (SUD) scale, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and the Burnout Inventory. We created our data collection methods with Survey Monkey (http://SurveyMonkey.com), which provides electronic self-access and prevents multiple data entries from the same person, making it easier to collect and track data (Survey Monkey-Survey Development Software, http://www.surveymonkey.com, last data entry: 5/5/2020). Confidentiality was assured by completely disabling electronic and IP address records to obtain anonymous responses.

Descriptive characteristics form

This form was developed by the researchers to include participants' age, gender, marital status, educational status, and how many hours worked per week.

The subjective units of distress scale (SUD)

Wolpe developed the SUD scale in 1973. This self-report, which is widely used, evaluates the individual's level of subjective distress on a scale of 0 to 10. A score of 0, indicates that there is no sense of distress and 10 indicates that the distress is almost unbearable. Participants rate the degree of distress they feel at that moment and state the score. This score provides concrete and basic data concerning the subjective state of the person at the time of implementation and reflects the change at the end of the application. In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the SUD scale was 0.89.

The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI tx-1)

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory has two separate scales, the State Anxiety Scale and the Trait Anxiety Scale.27 The State Anxiety Scale was used in this study. Öner and Lecompte28 have confirmed the validity and reliability of the test's Turkish version. The State Anxiety Scale consists of 20 questions about emotions, thoughts, and behaviors which are related to anxiety. The choices on this scale range from 1 (no anxiety) to 4 (extreme anxiety). Possible scores on the Scale range from 0 to 19 points (interpreted as meaning no state anxiety), 20 to 39 points (mild), 40 to 59 points (moderate), 60 to 79 points (severe), and 80 points and azbove (very severe state anxiety). Cronbach's alpha for the State Anxiety Scale was 0.93, while for this study it was 0.84.

The burnout scale

The Burnout Scale is designed to measure burnout levels in professionals.29 We used a Turkish adaptation of a standardized burnout scale whose its reliability and validity were confirmed by Çapri.30 It is a 7-point Likert type scale consisting of 21 items. A rating of 1 indicates “never” and a rating of 7 indicates always. Four of the items (3, 6, 19, 20), however, are scored in reverse. An increase in the score indicates an increase in burnout and a decrease in the score indicates a decrease in burnout. In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the burnout scale was 0.84.

Procedures

Before participating in the study, the nurses were randomized into to the intervention or control group. Before being assigned to group, the nurses were interviewed online, informed about the study, and their consent was obtained. Following the completion of the study, EFT was offered to the participants in the control group. Data collection was carried out online with Survey Monkey and interviews were conducted using Zoom.

Control group

After completing the Descriptive Characteristics Form, a SUD rating, the STAI-I, and the burnout scale, participants in the control group were asked to stay comfortable in a calm and tranquil environment for the next 15 min. At the end of this period, they were asked to again give a SUD rating and complete theSTAI-I and burnout scale.

Implementation of EFT

The 35 nurses in the EFT group were divided into 7 subgroups of 5 participants each. After completing the Descriptive Characteristics Form online, a time for the meeting was determined in collaboration with the participants in each subgroup. They were also asked to stay comfortable in as calm and tranquil an environment as possible during the session. The EFT treatment was provided by the first author, who was certified in EFT. Each 5-person group began by having the participants complete the pre-test SUD, the STAI-I, and the burnout scale via SurveyMonkey. EFT was applied to each group of nurses in a single session of approximately 20 min. At the end of the session, participants again completed the post-test SUD, the STAI-I, and the burnout scale.

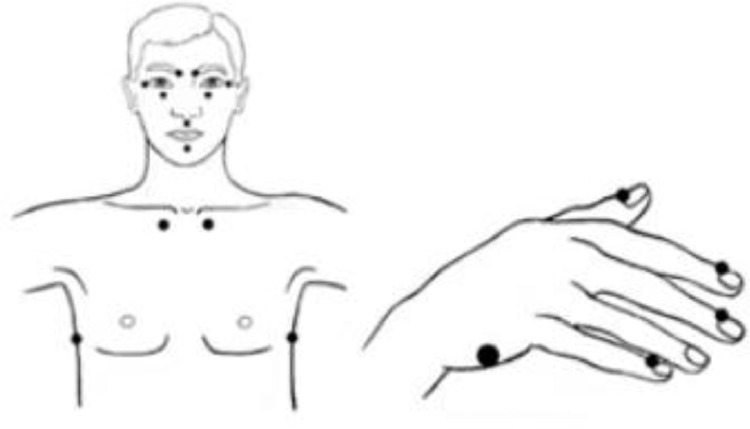

The EFT session began by presenting the participants with a picture of the acupressure points (Fig. 2 ) and showing them how to gently tap on them using their index and middle fingers. After this demonstration, the participants followed the basic steps of an EFT session, following the researcher's example:

-

1

Identify an anxiety-evoking issue and determine the SUD level.

-

2

Creating a personal acceptance and reminder statement in the general form of "I accept myself despite this ………."

-

3

Tapping seven times on each acupressure point shown in Fig. 2.

-

4

After tapping these points, the affirmation/reminder statement is repeated.

-

5

A sequence of physical movements and vocalizations called “The Nine Gamut Procedure” is carried out.

-

6

Steps 3 and 4 are repeated.

- 7

Fig. 2.

EFT tapping points

(http://www.eftuniverse.com/images/pdf_files/EFTMiniManual.pdf).

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted by a researcher who was blind to group assignment. After importing data from SurveyMonkey, it was then imported into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, Illinois, version 25.0 and analyzed by an investigator who was blinded to treatment condition. The data had, according to the Shapiro Wilks test, a non-normal distribution. For the statistical evaluation, Pearson Chi-Square, Mann Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis H, and Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests were used. All results were evaluated at p<.05 and a confidence interval of 95%.

Results

The 72 nurses completing the study included 64 females and 8 males. Mean age was 33.45±9.63 years. No statistically significant pre-intervention differences were found between the groups on demographic variables (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Distribution of descriptive characteristics of nurses by group (N = 72).

| Groups | EFT | Control | x2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n = 35) | (n = 37) | p* | |

| Age | Mean ± SD 33.54 ± 9.83 | 33.37 ± 9.58 | .042 | |

| .943 | ||||

| Weekly work hours | Mean ± SD 76.2 ± 6.93 | 76.16 ± 6.62 | 1.935 | |

| .967 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 32 | 91.4 | 32 | 86.5 |

| Male | 3 | 8.6 | 5 | 13.5 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 21 | 60 | 22 | 59.5 |

| Single | 14 | 40 | 15 | 40.5 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| High school health education | 3 | 8.6 | 4 | 10.8 |

| Associate degree | 4 | 11.4 | 2 | 5.4 |

| Bachelor's degree | 22 | 62.9 | 26 | 70.3 |

| Master's degree | 6 | 17.1 | 5 | 13.5 |

Note:.

Chi-squared test, n: Number of participants,%: Percentage, SD: Standard Deviation, EFT: Emotional Freedom Techniques, p < 0.05.

Stress levels

Table 2 compares SUD score averages pre- and post-test within each group and between the groups. The mean SUD score reduction on the post-test for the EFT group was highly significant (p<.001). The mean post-test SUD scores for the control group was statistically identical to the pre-test. These results support Hypothesis 1.

Table 2.

Comparison of score averages from the Subjective Units of Distress Scale before and after application according to groups.

| Groups Scale | EFT Group (n = 35) Mean ± SD (Min -Max) | Control Group (n = 37) Mean ± SD (Min - Max) | Z⁎⁎ | p | %95 CI Lower-Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD | Before | 7.82 ± 1.33 5–10 |

7.48±1.36 4–9 |

0.05 0.287 | −3,12 3,25 |

| After | 2.85 ± 1.21 1–6 |

7.40 ± 1.53 4–9 |

1.935 < 0.001 | −5201 −3,89 |

|

| Z*p | 16.58 < 0.001 | .286 0.776 |

Note.

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Mann- Whitney U test, SUD: The Subjective Units of Distress Scale, n: Number of the participant, SD: Standart Deviation, CI : Confidence Interval of the Difference.

Anxiety levels

Table 3 compares the anxiety score averages pre- and post-test within each group and between the groups. The mean pre-test anxiety score did not differ significantly between the groups. The mean anxiety score reduction on the post-test for the EFT Group was highly significant (p<.001). The mean post-test anxiety score for the Control Group was statistically identical to the pre-test. These results support Hypothesis 2.

Table 3.

Comparison of score averages from the State Anxiety Scale before and after application according to groups.

| Groups Scale | EFT Group (n = 35) Mean ± SD | Control Group (n = 37) Mean ± SD | Test Z⁎⁎p | %95 CI Lower-Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Anxiety Scale | Before | 67.68 ± 9.05 44–80 |

64.7 ± 8.05 45–80 |

.36 .14 |

−1.03 7.00 |

| After | 32.25 ± 4.67 25–39 |

64.43 ± 7.68 45–80 |

4.63 < 0.001 |

−35.18 −29.16 |

|

| Z*p | 19.13 < 0.001 | 1.00 0.324 |

Note.

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Mann- Whitney U test, n: Number of the participant SD: Standart Deviation, CI : Confidence Interval of the Difference.

Burnout levels

Table 4 compares the burnout score averages pre- and post-test within each group and between the groups. The mean pre-test burnout score did not differ significantly between the groups. The mean burnout score reduction on the post-test for the EFT Group was highly significant (p<.001). The post-test burnout score for the Control Group was statistically identical to the pre-test. These results support Hypothesis 3.

Table 4.

Comparison of score averages from the Burnout Scale before and after application according to groups.

| Scale | Groups | EFT Group (n = 35) Mean ± SD | Control Group (n = 37) Mean ± SD | Test Z⁎⁎ p | %95 CI Lower-Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout Scale | Before | 3.62 ± 0.76 2–5 |

3.56 ± 0.72 2–5 |

.055 .724 |

−0.282 .404 |

| After | 2.48 ± 1.06 1–4 |

3.43 ± 0.76 2–5 |

6,79 < 0.001* |

−1.38 - 0.511 |

|

| Z* p | 5.25 < 0.001* | 1.405 0.169 |

Note.

Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Mann- Whitney U test, n: Number of the participant, SD: Standart Deviation, CI : Confidence Interval of the Difference.

Discussion

The current COVID-19 outbreak has led to major changes in the healthcare system worldwide. Increased workload, long working hours, discomfort caused by personal protection equipment, fear of contamination, and most importantly obscurity, may lead to burnout.11 , 32 Nurses play a key role in fighting the COVID-19 infection. Their physical and psychological safety is of paramount importance. According to an analysis of 14 studies conducted on healthcare professionals who care for COVID-19 patients, serious levels of anxiety and depression symptoms were detected in up to 14.5% of the participants.33

A challenge in offering support for nurses and other healthcare workers impacted by the COVID-19 crisis is that the demands on their time are already a source of stress, so finding the time for the intervention may in itself contribute to further distress. Numerous studies have found EFT to be an effective and rapid treatment for stress, anxiety, and burnout.

EFT has been applied in many areas in which individual psychotherapy is not practical, such as the aftermath of earthquakes and other natural disasters, following terrorist attacks, and refugee camps.34 In the current study, a single group EFT session, within the convenience of online delivery, led to highly significant reductions stress, anxiety, and burnout scores.

Limitations

This pilot study produced a surprising finding. A single 20-minute online group treatment was effective in reducing stress, anxiety, and burnout in nurses working with COVID-19 patients. These results need to be confirmed through replication by independent investigators. The design of such replications could be strengthened by supplementing the checklist and SUD scores with interviews or physiological measures. In other EFT studies, favorable post-treatment changes have been found in biological indicators such as cortisol levels and the expression of genes that are involved with stress.14 Follow-up investigation on the durability of the outcomes would lend confidence about the ultimate value of the intervention. Future studies should also utilize EFT therapists who are not part of the research team.

Conclusion

As frontline workers in the treatment of COVID-19, nurses are exposed to substantial physical and emotional pressures which may take a toll on their mental health. A brief, single-session, online group intervention utilizing EFT was effective in significantly reducing stress, anxiety, and burnout. While several questions remain unanswered, such as how durable these benefits will prove to be, the intervention is fast and easy to provide, and it could be applied to nurses treating COVID-19 worldwide.

Funding

This research was not funded.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Contributions: Study design: BD, DI; data collection and management: BD, DI; data analysis; BD; manuscript preparation: DI, BD.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.explore.2020.11.012.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Heatlh Organization; 2020. WHO Characterizes COVID-19 As a Pandemic.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen (Accessed March 13, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 2.News in Turkey, Coronavirus scientific committee meeting; 2020. https://www.medimagazin.com.tr/guncel/genel/tr-saglik-bakani-fahrettin-kocaenfekte-olan-7428-saglik-calisanimiz-var-11-681-88528.html. (Accessed on 5 May 2020).

- 3.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew N.W., Lee G.K., Tan B.Y., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J., et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasangohar F., Jones S., Masud F.N., Kash B.A. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume ıntensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2020;20 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866. https://doi.org/1213/ANE.0000000000004866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin J. Mental health care for survivors and healthcare workers in the aftermath of an outbreak. Psychiatry of pandemics. D. Huremović (ed.) Springer Nat, Switzerland AG. 2020;16:127–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-15346-5_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mo Y., Deng L., Zhang L., et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1111/JONM.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Y.T., Yang Y., Li W., Zhang L., Cheung T., et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun N., Shi S., Jiao D., et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fessell D., Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal P., Bingemann T.A., Greenhawt M., et al. Clinician wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic: extraordinary times and unusual challenges for the allergist/immunologist. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Church D., Brooks A.J. The effect of a brief EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) self-intervention on anxiety, depression, pain and cravings in healthcare workers. Integr Med Clin J. 2010;9:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rancour B. The emotional freedom technique finally, a unifying theory for the practice of holistic nursing, or too good to be true. J Holist Nurs. 2017;35:382–388. doi: 10.1177/0898010116648456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinstein D. Energy psychology: efficacy, speed, mechanisms. Explore. 2019;15:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vural P.I., Aslan E. Emotional freedom techniques and breathing awareness to reduce childbirth fear: a randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sezgin N. The effects of a single emotional freedom technique (EFT) session on an induced stress situation. DTCF J. 2017;53:329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig G. The Gary Craig official EFT™ training centers. 2004. https://www.emofree.com/eft-tutorial/tapping-basics/how-to-do-eft.html/ (Accessed April 05, 2020).

- 18.Hartmann S. Energy EFT: next generation tapping & emotional freedom technique. Pegasus Yayınları;. Duru E., İstanbul. 2016;1:13–254. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghamsari M.S., Lavasani M.G. Effectiveness of emotion freedom technique on pregnant women's perceived stress and resilience. J Educ Sociol. 2015;6:118–122. doi: 10.7813/jes.2015/6-2/26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatwin H., Stapleton P., Porter B., Devine S., Sheldon T. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and emotional freedom techniques in reducing depression and anxiety among adults: a pilot study. Integrat Med. 2016;15:27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaesser A.H., Karan O.C. A randomized controlled comparison of emotional freedom technique and cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce adolescent anxiety: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23:102–108. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clond M. Emotional freedom techniques for anxiety: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204:388–395. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The State Council of China. A notification to set up nation wide psychological assistance hot lines against the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Published February 2, 2020. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/ 02/content_5473937.htm. (Accessed March 3, 2020).

- 24.Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hersch R.K., Cook R.F., Deitz D.K., et al. Reducing nurses' stress: a randomized controlled trial of a web-based stress management program for nurses. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;32:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline J.A., VanRyzin K., Davis J.C., Parra J.A., Todd M.L., Shaw L.L., et al. Randomized trial of therapy dogs versus deliberative coloring (art therapy) to reduce stress in emergency medicine providers. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(4) doi: 10.1111/acem.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spielberger C.D., Gorsuch R.L., Lushene R.E. Consulting Psychologists; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. Manual for State and Anxiety Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Öner N., Le Compte A. 1 ed. Bogazici University Publications; Istanbul: 1983. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pines A.M., Aronson E. Free Press; New York: 1988. Career burnout: Causes and Cures. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Çapri B. Turkish adaptation of the burnout measure: a reliability and validity study. Mersin Univ J Fac Educ. 2006;2:62–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Church D., De Asis M.A., Brooks A.J. Brief group intervention using EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) for depression in college students: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Res Treat. 2012;1–7 doi: 10.1155/2012/257172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moazzami B., Razavi-Horasan N., Moghadam A.D., Farokhi E., Rezaei N. COVID-19 and telemedicine: immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well-being. J Clin Virol. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohlken J., Schömig F., Lemke M.R., Pumberger M., Riedel-Heller S.G. COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers. Psychiat Prax. 2020;47:190–197. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Church D., House D. Borrowing benefits: group treatment with clinical emotional freedom techniques ıs associated with simultaneous reductions in posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression symptoms. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2018;23:1–4. doi: 10.1177/2156587218756510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.