Abstract

Management of the global crisis of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic requires detailed appraisal of evidence to support clear, actionable, and consistent public health messaging. The use of cloth masks for general public use is being debated, and is in flux. We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and Google for articles reporting the filtration properties of flat cloth or cloth masks. We reviewed the reference lists of relevant articles to identify further articles and identified articles through social and conventional news media. We found 25 articles. Study of protection for the wearer used healthy volunteers, or used a manikin wearing a mask, with airflow to simulate different breathing rates. Studies of protection of the environment, also known as source control, used convenience samples of healthy volunteers. The design and execution of the studies was generally rigorously described. Many descriptions of cloth lacked the detail required for reproducibility; no study provided all the expected details of material, thread count, weave, and weight. Some of the homemade mask designs were reproducible. Successful masks were made of muslin at 100 threads per inch (TPI) in 3 to 4 layers (4-layer muslin or a muslin-flannel-muslin sandwich), tea towels (also known as dish towels), made using 1 layer (2 layers would be expected to be better), and good-quality cotton T-shirts in 2 layers (with a stitched edge to prevent stretching). In flat-cloth experiments, linen tea towels, 600-TPI cotton in 2 layers, and 600-TPI cotton with 90-TPI flannel performed well but 80-TPI cotton in 2 layers did not. We therefore recommend cotton or flannel at least 100 TPI, at least 2 layers. More layers, 3 or 4, will provide increased filtration but there is a trade-off in that more layers increases the resistance to breathing. Although this is not a systematic review, we included all the articles that we identified in an unbiased way. We did not include gray literature or preprints. A plain language summary of these data and recommendations, as well as information on making, wearing and cleaning cloth masks is available at www.clothmasks.ca.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TPI, threads per inch, the sum of the warp plus weft thread count per inch; WHO, World Health Organization

Article Highlights.

-

•

Of the 25 articles that described studies of the filtration properties of cloth or cloth masks, some of which included medical masks and N95 respirators as comparators, most used surrogates for filtration, sometimes graded by particle size, and some used bioaerosols, usually bacterial. A minority of studies used virus; no study used severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

-

•

Studies of the filtration properties of flat cloth used a variety of methods, few of which were the equivalent to the standard methods used by ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials).

-

•

The design and execution of the studies was generally rigorously described; the number of replicates and variance of estimates was less well described, and it was unusual to find statistical comparisons between different types of cloth or types of mask.

-

•

Many descriptions of cloth were lacking in the detail required for reproducibility; no study gave all the expected details of material, thread count, weave, and weight.

-

•

Although no direct data with clinically important outcomes are available, this study found that cloth masks can offer substantial filtration, in some cases equivalent to some medical masks.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 2 resulting in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has, at the time of this writing, claimed at least 600,000 lives.1 The management of this global crisis requires detailed appraisal of evidence to support clear, actionable, and consistent public health messaging. The use of cloth masks for general public use is being debated, and is in flux: in April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) changed its position from “not recommended under any circumstance”2 to “there is no current evidence to make a recommendation for or against their use,”3 recognizing that, “decision makers may be moving ahead with advising the use of non-medical masks,” as was indeed occurring.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 On June 5, 2020, the WHO updated its guidance further “to advise that to prevent COVID-19 transmission effectively in areas of community transmission, governments should encourage the general public to wear masks in specific situations and settings as part of a comprehensive approach to suppress SARS-CoV-2 transmission.”9

In early March 2020, the WHO estimated that 89 million masks would be needed each month, globally, for medical purposes alone,10 highlighting the importance of directing the supply of medical masks and respirator-type masks (eg, N95s) to medical use. Nonmedical masks will be needed for the other purposes outlined. Cloth masks potentially offer a reusable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly solution.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and Google for articles on the filtration properties of flat cloth or cloth masks or face coverings using the search terms cloth, fabric, gauze, cotton, mask, and filtration and synonyms. We reviewed the reference lists of relevant articles and identified further articles. Our selection of articles for this review was unbiased, ie, it did not depend on the direction of the results. We did not conduct a systematic review or search gray literature. We identified 25 articles that described filtration properties of cloth or cloth masks, some of which included medical masks and N95 respirators as comparators. This review summarizes a century of evidence on the efficiency of cloth and cloth masks to reduce transmission of droplets and aerosols (Supplemental Table, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org).11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 We argue that this body of work should inform decisions in the context of reducing the transmissibility of COVID-19. Physical distancing, hand washing, and disinfection of surfaces remain the cornerstones of policy, and we stress that we are not discussing cloth masks as a means of relaxing these interventions or as a replacement for formal personal protective equipment (PPE) for high-risk workers.

What Are the Standards in This Literature?

When we breathe, eat, speak, sing, cough, or sneeze, particles are released into the environment. The size distribution of these particles varies with the activity, as does their velocity and their trajectory. Although technically all these particles of liquid (respiratory secretions) suspended in gas (air) are aerosols, we recognize a useful distinction between coarse particles (sometimes called droplets), which are usually defined as greater than 5-μm aerodynamic diameter, and aerosols, which are particles of less than 5-μm aerodynamic diameter. Exhaled secretions may contain virus particles, which are nanoparticles of much less than 1-μm.

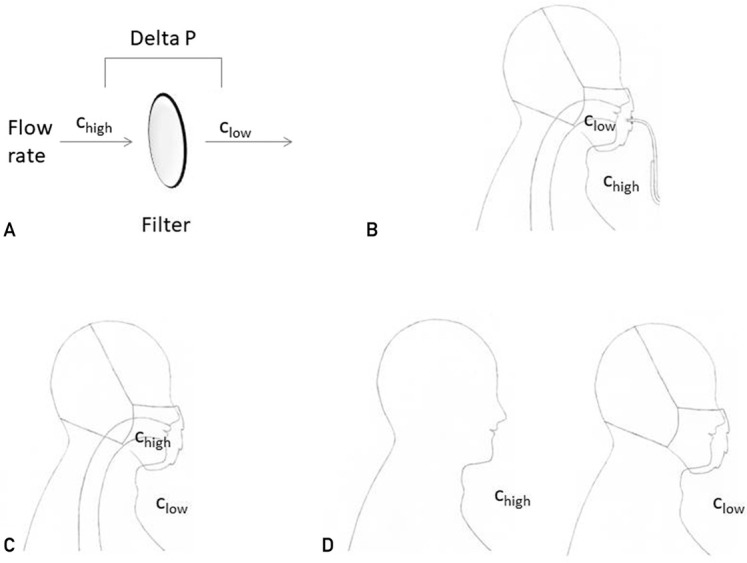

Filtration efficiency is the proportion of particles blocked by a filter (usually expressed as a percentage) and assessed using surrogate markers, not directly with transmissible pathogens (Figure ; Supplemental Figure 1, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). Some surrogates are nonbiological, such as ambient particles, or aerosols of diesel combustion or saline; others are bioaerosols, usually bacterial. Filtration standards specify detail for testing of mask materials (equipment, surface area tested, air flow, particle type and size). Medical masks (also known as dental masks and surgical masks) are certified according to the standards set by ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials).36 Canada uses these US standards for mask materials, which define 3 levels (1 to 3) of mask according to particle filtration efficiency greater than 95%, 98%, and 98% for the flat material, respectively. Increasing resistance to splashing with synthetic blood further distinguishes level 2 and level 3 masks. Particle filtration efficiency of the flat mask material is assessed using latex spheres of 0.1 μm and bacterial filtration efficiency using aerosolized Staphylococcus aureus at a mean particle size of 3 μm.36 The material for respirator-type masks, in North America called N95s, is certified according to standards set by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.37 The relationship between particle size and filtration efficiency is not linear, with small particles having consistently lower efficiency, but U-shaped, with the lowest filtration efficiency usually around 0.3 μm, which is sometimes called the most-penetrating-particle size.23 , 37 Mask material for respirators is therefore tested at 0.3 μm, and particle filtration efficiency greater than 95% is required.37 The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration and Canadian Standards Association standard Z94.4 further require that N95 masks be fitted to the individual who will wear them.38 , 39 Fit assesses both penetration through the mask material and leak around the mask edge. A quantitative fit testing device, the TSI PortaCount, measures saline particles in the 0.02- to 1-μm range, inside and outside the mask. A ratio of 100 particles outside the mask to 1 particle inside, known as a fit factor, is required; this ratio is equivalent to filtration efficiency of 99% (Supplemental figure 1). A nonquantitative alternative standard is to test with a hood and a strong-tasting aerosol such as saccharin.38 No fit testing is required for medical masks.

Figure.

Schematic showing different types of filtration experiments. A, An experiment on a flat cloth sample or mask material sample (the filter). The surface area of the sample tested, the particle size, particle composition, and flow rate should be defined. The pressure drop across the filter under these or other specified conditions can be measured. There is no edge leak. All the particles that contribute to the concentration on the protected side of the filter have penetrated the material. The TSI 8130 filter tester (TSI Incorporated) is an example of such a system. Using this type of experiment, ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials) defines the standards for testing material for medical masks, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health defines the standards for testing material for respirators (N95-type masks). B, An inward protection experiment on a mask using a human volunteer or a manikin. For human volunteers, the concentration inside the mask is measured using a thin-walled tube called a probe that fits across the mask material. For a manikin, a pump will simulate breathing, and the concentration inside the mask can be measured at any point in the circuit. The concentration outside the mask is measured from the surrounding air. The TSI PortaCount is an example of such a system and can be used with human volunteers or with a manikin. When the particles to be measured are inert and harmless, such as the saline aerosol typically used with the PortaCount, the experiment can be conducted in an ordinary room without special conditions. The concentration of particles on the protected side (the inside) is a combination of penetration of the mask (through the material) and edge leak (around the material); it measures both the material and the fit. In experiments using human volunteers, a variety of activities can be undertaken to further challenge the mask (eg, deep breathing, head movement, bending). In experiments using manikins, the flow rate can be adjusted to simulate different levels of minute respiration corresponding to different activity levels. For medical masks, no relevant standards have been defined. For respirators (N95-type masks), the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires that N95 masks be fitted to the individual who will wear them. Fitting can be done quantitatively using a device such as the PortaCount or nonquantitatively using a strong-tasting substance such as saccharin. C, An outward protection experiment on a mask using a manikin. The aerosol is generated and passed through the manikin into the mask. The concentration of the aerosol on the source side can be measured at any point in the circuit. The concentration of the aerosol on the protected side is measured from the environment. The apparatus is protected in a chamber filled with filtered air to ensure that all particles outside the mask have come from the manikin. The concentration of particles on the protected side (the outside) is a combination of penetration of the mask (through the material) and edge leak (around the material). There are no standards that relate to this design. D, An outward protection experiment using human volunteers. The aerosol is generated through human activity—breathing, talking, or coughing. Usually these tests are bioaerosol experiments measuring normal human mouth flora or pathogens from volunteers who are unwell. (In some experiments, to standardize the experiment and to increase the concentration of bacteria in the aerosol, volunteer investigators contaminated their mouths with nonpathogenic bacteria and studied transmission specifically of that species.) There are no standards that relate to this design. Chigh = particle concentration on the source side of the filter; Clow = particle concentration on the protected side of the filter; Delta P = pressure drop across the filter.

The diameter of SARS-CoV-2 virus has been reported as between 0.065 and 0.140 μm.40 In contrast, the space between threads in many woven cloths is visible to the naked eye, and even in high thread count fabric, the gaps between fibers are of the magnitude of 5 to 15 μm.23 In lower thread count fabric, gaps as large as 50 to 200 μm are expected and observed.23 , 41 , 42 It is counterintuitive that cloth stops particles smaller than 5 μm; however, particles of this size encounter cloth fibers and are filtered through the 3 physical principles of impaction, sedimentation, and diffusion.43

Transmission of virus is usually not as isolated virions but in larger particles combined with respiratory secretions. Although the literature describing the size distribution of particles generated by activities such as breathing, coughing, and sneezing is not completely consistent, it appears that even for the less explosive activities, a proportion of particles are greater than 1 μm, and for coughing and sneezing, particles in the 10-μm and even 100-μm range have been observed,44 although other reports suggest peak particle size around 1 to 5 μm.45 The reasons for these large differences among studies are not apparent. The particle size used for testing medical masks is 0.1 μm.36 If individual particles contain more than one virion and larger particles contain more virions than smaller particles, filtration efficiency for virions reaching the environment may exceed expectations based on testing using latex test nanoparticles.

Cloth is woven (crossing threads, known as warp and weft), knitted (interlocking loops of fiber), or felted (compressed disorganized fibers). Woven cloth is further described by its weave. In plain weave, fibers cross at 90 degrees. Twisted weave gives a diagonal stripe to the finish and is known as twill weave; a common example is denim. When the warp and the weft are different numbers of threads in a given distance (conventionally, an inch), thread count may be expressed by 2 numbers, eg, 20 × 14. Thread count expressed as a single number, threads per inch (TPI), is the sum of the warp plus weft thread count per inch. The finish may be plain or raised to fuzziness, which is called a nap. Some fabrics, called terry, have projecting loops of fiber to increase absorbance. The overall heaviness is described by its weight per surface area (g per square metre or gsm). Very high thread counts (>300) are usually obtained by using very thin fiber, and the resulting material may be very fine (light-weight, such as some bed linen).

Surgical gauze, plain woven cotton or linen (such as most dish towels [United States] or tea towels [United Kingdom], ie, flat cloths used for drying dishes), muslin, buttercloth (a cloth used for straining in the manufacture of butter), and some bed linen are plain-weave unnapped cloth. Flannel, commonly used for nightwear and some bed linen, is a plain-weave napped cloth, often of cotton. T-shirt material is usually knitted jersey; the proportion of cotton to man-made fiber and the weight vary. Terry is used for most bath and hand towels.

Commercial disposable masks are made from nonwoven synthetic fibers in bonded layers. These masks are unsystematically called medical masks, face masks, surgical masks, dental masks, and procedure masks. We use the term medical masks.

Can Fabric Block Coarse and Fine Particles?

The increasing effectiveness of multiple layers of cloth to reduce transmission was demonstrated in 1919 in a series of experiments using controlled sprays and real coughing to create bioaerosols.34 Bacterial counts were used as the surrogate marker. Filtration efficiency increased with thread count and layers and was consistently greater, at any given total thread count, the fewer the layers (eg, 1 layer with a mean thread count of 42 provided greater filtration than 2 layers with a thread count of 22 [total thread count of 44]) (Supplemental Figures 2-4, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). At all distances, total thread counts above approximately 300 TPI were associated with greater than 80% filtration efficiency. Other investigators confirmed these observations using similar designs,16 , 19 , 22 , 24 one study observing that twill weave cotton was associated with 94% filtration efficiency compared with 98% and 99% for material from 2 medical masks.16

Filtration efficiencies of 28% to 73% were reported for single layers of bath towel and cotton shirt tested with 2-μm bacterial particles.18 For linen tea towel fabric, filtration efficiency for bacteria was 83% with 1 layer and 97% with 2 layers compared with medical mask material at 96%.14 , 46 For virus, one layer of tea towel had 72% efficiency, and one layer of T-shirt fabric had 50% efficiency compared with 89% for mask material.14

Results are dependent on the type of cloth studied. For sodium chloride aerosol, 3 commercially available cloth masks and single layers of scarfs, most sweatshirts, T-shirts, and towels were associated with filtration efficiency of 10% to 40%.29 The cloth from the mask studied in the single randomized controlled trial (RCT) was tested using a TSI filter tester according to Australian and New Zealand standards for respirators.26 Filtration efficiency for the cloth was 3% compared with the medical mask, which tested at 56%. The trial is described in detail subsequently.

Table 1 summarizes studies that use modern methodology Figure to test the filtration efficiency of flat cloth, organized by fabric type, and includes information on medical mask material and respirator material comparators.14 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 29 , 35 , 46 Few of these studies used standardized methodology, and their results are not directly comparable. Collectively, they reveal that even at low thread counts and layers, and for aerosols, some kinds of cloth block substantial percentages of transmission. Filtration efficacy of greater than 50% has been observed for single layers of high thread count cotton, for linen and cotton tea towels, for some T-shirt materials, some towels, and some man-made materials sold as cloth masks; efficiency increases with layers, and efficiency for virus is of the same order of magnitude as that for bacteria.

Table 1.

Summary of Filtration Efficiency for Flat Cloth, Including Details of Methodology: Aerosol Used, Aerosol Size, and Flow Ratea,b

| Reference, year | Composition | Weight, weave, thread count | Efficiency |

Aerosol | Measured aerosol size | Flow rate (L/min) | Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Layer | 2 Layers | |||||||

| Cotton | ||||||||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | “Quilters’ cotton” | 80 TPI | 4% | 32% | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| 80 TPI | 3% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~9c | No | ||

| 80 TPI | 6% | 50% | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | 3.5c | No | ||

| 80 TPI | 34% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~9c | No | ||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Cotton 600 TPI (#1 in “Hybrids” below) | 600 TPI | 76% | 85% | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| 600 TPI | 98% | 99.5% | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| Jung et al,21 2014 | Gauze, cotton | NA | 1% | 1%; 4 layers, 4% | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 85 | NIOSH |

| Davies et al,14 2013 | T-shirt: 100% cotton | Knit | 69% | 71% | Bacillus atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| Knit | 51% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | T-shirt, Hanes: 100% cotton | Knit | 9% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 12% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | T-shirt, cotton | Knit 157 g/m2 | 22% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Sweater, cotton | Knit 360 g/m2 | 26% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Towel, Pem-America: 100% cotton | NA | 23% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 49% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Towel, Pinzon: 100% cotton | NA | 30% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 58% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Towel, AQUIS: 100% cotton | NA | 33% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 0% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Scarf: cotton | NA | 62% | 71% | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 49% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Scarf, Pocket Square: 100% cotton | NA | 0% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 0% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Scarf, Seed Supply: 100% cotton | NA | 1% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 7% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Pillowcase | NA | 61% | 62% | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 57% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Pillowcase: 100% cotton | 116 g/m2 | 5% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Jung et al,21 2014 | Handkerchief, cotton | NA | 1% | 2%; 4 layers, 4% | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 85 | NIOSH |

| Linen | ||||||||

| Davies et al,14,46 2013 | Tea towel, linen | NA | 83% | 97% | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 72% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Linen | NA | 60% | NA | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 62% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Silk | ||||||||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Silk | NA | 58% | NA | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 54% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Silk, 100% (#2 in “Hybrids” below) | 39 g/m2 145 TPIe | 54% | 65%; 4 layers, 84% | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| 39 g/m2 145 TPIe | 55% | 66%; 4 layers, 89% | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Napkin, silk | Woven84 g/m2 | 5% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Manmade | ||||||||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Chiffon: 90% polyester, 10% spandex (#3 in “Hybrids” below) | 195 TPIe | 58% | 86% | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| 195 TPIe | 24% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~9c | No | ||

| 195 TPIe | 73% | 90% | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| 195 TPIe | 53% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~9c | No | ||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Interfacing material: polypropylene | Spunbond 30 g/m2 | 6% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Scarf, Walmart fleece: 100% polyester | NA | 25% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 14% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Toddler wrap: polyester | Knit 200 g/m2 | 18% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Exercise pants: nylon | Woven 164 g/m2 | 23% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Composites | ||||||||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Cotton mix | NA | 75% | NA | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 70% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Flannel: 65% cotton, 35% polyester (#4 in “Hybrids” below) | 90 TPIe | 55% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| 90 TPIe | 13% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~9c | No | ||

| 90 TPIe | 44% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| 90 TPIe | 46% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~9c | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Norma Kamali sweatshirt: 85% cotton, 15% polyester | NA | 8% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 26% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Hanes sweatshirt: 70% cotton, 30% polyester | NA | 19% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 15% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Faded Glory sweatshirt: 60% cotton, 40% polyester | NA | 6% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 12% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Dickies T-shirt: 99% cotton, 1% polyester | NA | 8% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 20% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Faded Glory T-shirt: 60% cotton, 40% polyester | NA | 0% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 15% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Paper | ||||||||

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Paper towel: cellulose | Bonded 43 g/m2 | 10% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Tissue paper: cellulose | Bonded 33 g/m2 | 20% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Zhao et al,35 2020 | Copy paper: cellulosef | Bonded 73 g/m2 | 99.9% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 32 | No |

| Hybrids | ||||||||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Cotton/silk (1 layer of #1 above,g 1 layer of #2 above) | NA | 96% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| NA | 97% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Cotton/chiffon (1 layer of #1 above,g 1 layer of #3 above) | NA | 97% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| NA | 99.5% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| Konda et al,23 2020 | Cotton/flannel (1 layer of #1 above,g 1 layer of #4 above) | NA | 95% | NA | NaCl solution | 75-100 nm | ~3.5c | No |

| NA | 96% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-3 μm | ~3.5c | No | ||

| Cloth mask material | ||||||||

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Commercial mask fabric A, bleached cotton | 96 TPI | 69% | NA | Staphylococcus aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Commercial mask fabric D, bleached cotton | 86 TPI | 43% | NA | S aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Commercial mask fabric B, calico | 160 TPI | 73% | NA | S aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Commercial mask fabric C, twill weave | NA | 94% | NA | S aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | Cloth mask A: 50% nylon, 40% polypropylene, 10% polyurethane | 1.22-mm thick | 29% | 59%; 4 layers, 75% | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| 1.22-mm thick | 60% | 70%; 4 layers, 94% | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | Cloth mask B: 84% nylon, 12% polyester, 4% spandex | 0.62-mm thick | 28% | 32%; 4 layers, 67% | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| 0.62-mm thick | 63% | 71%; 4 layers, 77% | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | Cloth mask C: 100% polyester | 0.29-mm thick | 18% | 50%; 4 layers, 55% | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| 0.29-mm thick | 45% | 78%; 4 layers, 81% | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | Cloth mask D: 100% polyester microfiber | 0.30-mm thick | 9% | 45%; 4 layers, 62% | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| 0.30-mm thick | 45% | 59%; 4 layers, 99% | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | Cloth mask E: 100% polyester microfiber | 2.77-mm thick | 27% | NA | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| 2.77-mm thick | 80% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jung & Kim,20 2015 | Cotton mask: surgical type, 4 distinct masks | NA | 23%, SD 27% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 85 | NIOSH |

| MacIntyre et al,26 2015 | Cloth mask | NA | 3% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | NA | AS/NZS 1716 |

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Respro Bandit | NA | 22% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 34% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Breathe Healthy | NA | 13% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 44% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Rengasamy et al,29 2010 | Breathe Healthy fleece | NA | 22% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 5.5 cm/s | No |

| NA | 13% | NA | NaCl solution | 1 μm | 17 cm/s | No | ||

| Medical mask material | ||||||||

| Davies et al,14 2013 | Mölnlycke Health Care Barrier 4239 | NA | 96% | NA | B atrophaeus | NA | 30 | No |

| NA | 90% | NA | Bacteriophage MS2 | NA | 30 | No | ||

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Hopes | Fine glass fiber with nonwoven fabric | 98% | NA | S aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| Furuhashi,16 1978 | Medispo | Fine glass fiber with nonwoven fabric | 99% | NA | S aureus | NA | 8 | US military standard, 1978 |

| MacIntyre et al,26 2015 | Medical mask material | NA | 56% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | NA | AS/NZS 1716 |

| Jang & Kim,20 2015 | R class respirator material | 1.81-mm thick | 91% | NA | NaCl solution | 0.3-0.5 μm | NA | No |

| NA | 100% | NA | NaCl solution | 2-5 μm | NA | No | ||

| Jung et al,21 2014 | Medical mask: surgical type, 4 distinct masks | NA | 41% SD 38% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 85 | NIOSH |

| Jung et al,21 2014 | Medical mask: dental type, 5 distinct masks | NA | 71% SD 12% | NA | NaCl solution | 75 nmd | 85 | NIOSH |

AS/NZS = Australia/New Zealand Standard; NA = not available; NaCl = sodium chloride; NIOSH = National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; TPI = threads per inch (number of threads in warp plus number of threads in weft).

For experimental details and additional studies, see Supplemental Table (available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org).

Konda et al23 measured cloth using a system that produced initial flow rates of 35 L/min and 90 L/min, respectively; however, when cloth was inserted, increasing the resistance, the flow rate decreased, probably by an order of magnitude (Supratik Guha, written communication, month year; and Konda et al23 correction). We have reflected this by reporting a flow rate that is the initial divided by 10 and by indicating that it is approximate (~); we thought this was preferable to giving no indication. The experiments in this article included some readings done with a gap past the filter, to simulate edge leak. We have extracted these data in the Supplementary Material but here present the results of flat cloth with no gap. When multiple data points were available, we extracted data closest to 100 nm (used for testing particle filtration efficiency for medical masks, according to ASTM International standards) and 3000 nm (3 μm) (used for testing bioaerosol filtration efficiency for medical masks, according to ASTM International standards). To be conservative, we selected the closest point below the target particle size. Many original articles provided a measure of error variance. We have not included these data in this table for readability. They are often wide, in the 10% to 30% range. We report the SD for Jung et al21 because it reflects the differences in properties of a number of distinct masks of different materials (4 surgical, 3 dental, and 5 cotton; tested in triplicate for each design) that are not reported separately, not the error variance of a single mask. We did not extract data for N95 mask material and medical mask material from Konda et al23 because the methodology used by these investigators for testing fabric were under conditions different than those used for specifying fitted protective equipment such as the N95 respirators, which are tested under higher differential pressures and flows (Supratik Guha, written communication, month year).

TSI filter tester generates NaCl aerosol with a count mean diameter of 75 nm and geometric SD of 1.75 nm.

Calculated from pitch, the distance between the center of one thread and the next.

This was writing paper and obviously not breathable.

The 600-TPI cotton was used in the hybrid experiments (Supratik Guha, written communication, month year).

An important variable is airflow. In general, other experimental conditions being constant, lower filtration efficiencies would be expected with higher airflows, although this is not consistently observed, perhaps because of random error.23 , 29 Most testing of flat materials aims to simulate breathing through a mask, sometimes at high minute ventilation to simulate exertion.14 , 21 , 23 , 35, 36, 37 Lower flow rates, as observed in some studies,23 and flow rates as velocities29 require consideration in interpretation. Peak flow rates of 200 to 1300 L/min and peak velocities of 29 m/s have been observed for human coughs.45 None of the experiments that we identified on flat cloth aimed to simulate these conditions.

Does Wearing a Cloth Mask Prevent Coarse and Fine Particles From Reaching the Environment (Outward Protection or Source Control)

In a design in which volunteers, talking or coughing, sat at a table on which agar plates were arranged, masks of 3 to 8 layers of buttercloth (TPI ~90) blocked 100% of bacteria at all distances (Figure).15 Similar results were obtained by others.27 , 47 In another study, a 3-layer, 46 × 46 gauze mask (ie, TPI of 92 in each layer) reduced bacterial counts by 64% compared with no mask in the zone immediately in front of healthy volunteers who were talking.31 In a controlled box experiment using volunteers talking, a mask made of a sandwich of thin muslin and 4-oz flannel (136 g/m2) reduced bacteria recovered on sedimentation plates by more than 99% compared with the recovery from unmasked volunteers.17 Total airborne microorganisms were reduced by more than 99% and bacteria recovered from aerosols (<4 μm) by 88% to 99% compared with those recovered from unmasked volunteers. Another controlled box experiment with talking volunteers compared 4 medical masks and one commercially produced 4-layer cotton muslin (92 TPI48) reusable mask.28 Filtration efficiency, assessed by bacterial counts, was 96% to 99% for the commercial disposable masks and 99% for the commercial 4-layer muslin mask. For aerosols (<3.3 μm), filtration efficiencies were 72% to 89% and 89%, respectively.

Using a pattern based on a pleated medical mask, but without assistance, volunteers made 2-layer T-shirt masks with over-the-head elastic.14 , 49 Wearing the mask they had made, volunteers coughed twice into a box; at each particle size, homemade and medical masks were similar, with 71% and 86% efficiency, respectively, at the smallest particle size measured (0.65 to 1 μm) (P=.24; Table 2 ). We identified one disconfirming report, a study using a PortaCount (0.02 to 1 μm) on a manikin in which the efficiency of a 1-layer tea towel mask in reducing aerosols reaching the environment was 17% (Figure and Table 3 ).32

Table 2.

Filtration Efficiency According to Particle Diameter for Homemade 2-Layer T-Shirt and Disposable Commercial Medical . Masks From 21 Volunteers Coughinga

| Particle diameter (μm) | Filtration efficiency, outward |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Layer T-shirt mask | Medical mask | ||

| >7 | 67% | 44% | .14 |

| 4.7-7 | 61% | 61% | >.99 |

| 3.3-4.7 | 20% | 20% | >.99 |

| 2.1-3.3 | 85% | 89% | .70 |

| 1.1-2.1 | 84% | 94% | .31 |

| 0.65-1.1 | 71% | 86% | .24 |

| Total | 79% | 85% | .62 |

Recalculated from Davies et al.14 Bacterial filtration efficiency was calculated as (bacterial counts without mask − bacterial counts with mask)/bacterial counts without mask.

P values are our calculations, the difference between 2 proportions, using R (R foundation).

Table 3.

Filtration Efficiency in Inward and Outward Directions for Homemade and Medical Masks, 0.02-1 μm particles a,b,c

| Mask | Filtration efficiency |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inward |

Outward |

||

| Immediate | After 3 h | Immediate | |

| 1-Layer tea towel | 55%-69% | 63%-77% | 17% |

| Medical | 76%-81% | 74%-83% | 58% |

From 28 volunteers (inward, immediate), 22 volunteers (inward, after 3 hours), and data from a manikin wearing a mask (outward).

Recalculated from van der Sande et al.32 Filtration efficiency is calculated as 1 − (1/protection factor).

Both adults and children were studied in short term, with somewhat lower performance in children; we extracted the adult data for consistency with the rest of the literature. For each experimental condition, we extracted the highest and lowest median efficiencies from the data provided. Outward data were read from graphs. Because medians were reported, statistical testing was not possible.

These studies reveal that some multilayered cloth masks can have remarkable filtration efficiency in the outward direction, reducing all particles emitted by the wearer by 64% to 99% and aerosols by 72% to 99%, for some designs comparable with commercial medical masks.

Does Wearing a Cloth Mask Prevent Inhalation of Coarse and Fine Particles (Inward Protection or Personal Protection)?

Table 4 summarizes studies of cloth masks worn by volunteers or on a manikin Figure. In one study, the 3 authors made personalized cloth masks from heavy-duty T-shirt material, including 3 sets of ties and 8 layers of material at the front.13 Filtration efficiency, measured using a PortaCount (0.02 to 1 μm), was 99%, 92%, and 94% for the 3 individuals tested. (On this test, a respirator performing at 99% or greater would be considered a good fit.)

Table 4.

Summary of Filtration Efficiency for Cloth Masks, Inward Protection (Protecting the Wearer), Assessed at Less Than 1-μm Particle Sizea

| Reference, year | Cloth mask detailed description | Testing | Device, particle size | Details | Cloth mask filtration efficiency | Medical mask filtration efficiencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dato et al,13 2006 | T-shirt mask made by the authors to fit their own faces; 8-layer high-quality preshrunk cotton T-shirt fabric (Hanes heavyweight T-shirt) with 3 sets of ties | The authors as volunteers | PortaCount, 0.02-1 μm | Author 1 Author 2 Author 3 |

99% 92% 94% |

NA |

| Cloth mask |

Medical mask |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | After the other exercises | Initial | After the other exercises | |||||

| Davies et al,14,49 2013 | T-shirt mask made with a pattern by unskilled volunteers without assistance; 2-layer T-shirt fabric, pleated design | Volunteers | PortaCount, 0.02-1 μm | Normal breathing | 50% | 50% | 83% | 80% |

| Heavy breathing | 50% | NA | 86% | NA | ||||

| Shaking head | 50% | NA | 80% | NA | ||||

| Nodding | 50% | NA | 80% | NA | ||||

| Bending over | 0% | NA | 67% | NA | ||||

| Talking | 50% | NA | 83% | NA | ||||

| Overall | 50% | NA | 80% | NA | ||||

| Cloth mask |

Medical mask |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flow rate (L/min) |

flow rate (L/min) |

|||||||

| 8 | 19 | 8 | 19 | |||||

| Shakya et al,30 2017c | Purchased from street vendor, Kathmandu, Nepal, in 2014; simple cloth rectangles (layers unknown) with ear loop, cloth not specified | Manikin | Particle counter, 30 nm | Cloth mask 2 | 89% | 15% | 91% | 62% |

| Cloth mask 3 | 54% | 26% | NA | NA | ||||

| 100 nm | Cloth mask 2 | 57% | 32% | 94% | 70% | |||

| Cloth mask 3 | 57% | 27% | NA | NA | ||||

| 500 nm | Cloth mask 2 | 47% | 57% | 92% | 65% | |||

| Cloth mask 3 | 45% | 31% | NA | NA | ||||

| 1 μm | Cloth mask 2 | 69% | 54% | 99% | 96% | |||

| Cloth mask 3 | 85% | 49% | NA | NA | ||||

| Cloth mask |

Medical mask |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term | After 3 h | Short term | After 3 h | |||||

| van der Sande et al,32 2008 | Cloth mask, homemade, made of TD Cerise Multi teacloths (tea towel) (Blokker); 1-layer mask | Volunteers | PortaCount, 0.02-1 μm | Sitting quietly | 60% | 69% | 76% | 77% |

| Nodding | 55% | 63% | 79% | 78% | ||||

| Shaking head | 55% | 66% | 80% | 76% | ||||

| Reading | 69% | 77% | 81% | 83% | ||||

| Walking | 58% | 66% | 76% | 74% | ||||

NA = not available.

When a medical mask was included as a comparator, we have also provided the data for the medical mask.

We excluded cloth mask 1 because it had an exhalation valve that may have improved its performance. We included the latex particle data because they are comparable with other experiments but not the data obtained with diesel combustion particles (these data are provided in the Supplemental Table, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org).

In a study using healthy volunteers and a PortaCount (0.02 to 1 μm), a 2-layer homemade T-shirt mask provided 50% inward filtration efficiency during a range of activities, compared with 80% to 86% from a medical mask.14 , 49

In the study by Shakya et al,30 3 cloth masks and 1 medical mask purchased from street vendors in Kathmandu, Nepal, and 2 N95 masks were tested using a manikin. Test particles were polystyrene latex and diesel combustion particles. Cloth mask 1, which had a conical shape and an exhalation valve, performed as well as the 2 N95 masks: all 3 masks had approximately equal to 80% filtration efficiency for polystyrene latex particles across the range of particle sizes, from 30 nm to 2.5 μm. Cloth masks 2 and 3, simple rectangles with ear loops, had filtration efficiency of 1% to 65% for 30-nm particles and 65% to 75% efficiency for 2.5-μm particles. For diesel particles between 30 and 500 nm in diameter, filtration efficiency was 25% to 85%, 10% to 70%, and 10% to 25% for cloth masks 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and 55% to 85% for the surgical mask.

Similar results, filtration efficiencies of 55% to 77%, tested with aerosols (0.02 to 1.0 μm) were reported for a 1-layer tea towel mask (Table 3).32

In experiments using a manikin to identify leakage around the interface between mask and face, leakage was reduced by taping or by holding material in place with pantyhose.12

These studies found that one specific cloth mask performed as well as an N95 in excluding aerosols from the wearer,30 that complex, multilayer homemade masks can perform above 90%,13 and that simple 1-layer masks can perform similarly to medical masks.32 The poorest-performing masks had some inward filtration efficacy for aerosols.

Does Wearing a Cloth Mask Prevent Disease in Animal Experiments?

In rabbits exposed to aerosolized tubercle bacilli, tightly fitting 3- or 6-layer, 40 × 44 (84 TPI) gauze masks reduced the number of tubercles per rabbit from 28.5 in unmasked and 1.4 in masked rabbits, representing filtration efficacy of 95% (P=.003, our calculations).25 This controlled animal experiment reveals significant reduction in aerosol transmission of tuberculosis, usually considered an airborne organism, by multilayered cloth masks.

Have RCTs Been Conducted on the Effectiveness of Cloth Masks in Any Setting?

We identified a single RCT that compared continuous wear of a cloth mask with continuous and with as-needed wear of medical masks.26 The cloth masks used were tested on an industry-standard TSI device according to the standards used for N95-type mask material and were found to be unusually inefficient at 3%. Although data are not exactly comparable between studies, the observed filtration efficiency of 3% for this particular cloth mask material is the lowest for commercial cloth mask that we identified in any study (Table 1).16 , 20 , 26 , 29 The medical mask comparator, assessed at 56% filtration efficiency (as flat material), performed substantially better.26 Unsurprisingly given these properties, continuous cloth mask use, compared with continuous medical mask use, was associated with increased incidence of influenzalike illness (relative risk [RR], 13.3; 95% CI, 1.74 to 101). Participants in this study were health care workers on high-risk medical wards. The comparator groups were continuous medical mask use and medical mask use where indicated by the patient’s isolation status. The use of a cloth mask continuously meant that health care workers caring for patients requiring respiratory isolation wore a cloth mask in this context instead of a medical mask. This study has been widely discussed in the press and has not always been accurately represented. One report summarizes it as “actually increased the rate of infections among health care workers compared to those who wore surgical masks,” which could be interpreted as cloth masks actually causing harm.50 A 2015 article on this study carries the title, “Cloth Masks: Dangerous to Your Health?” and refers to “harm caused by cloth masks.”51 The study leaves us unable to draw conclusions about the efficacy or harms of wearing a cloth mask, compared with no mask, because there is no “no mask” comparison group. What we can infer from this study, however, is that in a health care setting, a device with 56% filtration efficiency prevents clinical illness compared with one with 3% filtration efficiency.

There is absence of evidence, then, rather than evidence of absence or evidence of harm, on whether cloth masks prevent transmission of clinical illness.

Does Wearing a Medical Mask in a Community Context Protect Oneself or Others?

On April 9, 2020, Greenhalgh et al52 identified 5 peer-reviewed systematic reviews on public mask wearing to prevent transmission of a wide range of respiratory pathogens and summarized them as absence of evidence; citing the precautionary principle, the authors advocated for public mask wearing. Using the framework of evidence-based medicine and the concept of risk-based decision making under uncertainty (ie, the absence of clear clinical evidence of benefit), we supported this position.53 Subsequently, in a meta-analysis of observational studies of risk of infection from the coronaviruses SARS-CoV-1, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and SARS-CoV-2, use of masks (respirators, medical masks, or 12- to 16-layer cloth masks) compared with no mask was protective in both health care settings (RR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.41; I 2 = 50%) and non–health care settings (RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.79; I 2 = 48%).54

Does Wearing a Cloth Mask in a Community Context Protect Oneself or Others?

The meta-analysis by Chu et al54 identified 3 observational studies of mask use in the community. The primary studies, reports of SARS-CoV-1 transmission in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Vietnam, did not identify the mask type used.55, 56, 57 One of these reports included only 9 participants wearing masks.55 In another of these reports, the odds ratio for infection associated with visiting an infected individual while wearing a mask compared with not visiting the infected individual was 1.8 (95% CI, 0.8 to 4.0) for one person wearing a mask, 1.9 (95% CI, 0.9 to 4.0) for both persons wearing a mask, and 4.2 (95% CI, 2.4 to 7.3) for neither wearing a mask.56 The third study reported an odds ratio for infection of 0.5 (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.9) for sometimes wearing a mask when going out and 0.3 (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.5) for always wearing a mask when going out compared with the referent of never wearing a mask when going out.57

The meta-analysis and detailed review of the primary studies advance our understanding from “absence of evidence” to the point where we have somewhat consistent observational evidence of a protective effect from mask wearing in the community, with a large effect size. It is plausible that masks protect people, and there is coherence between the data on community mask wearing and mask wearing in health care settings.58 However, the evidence is somewhat indirect: SARS-CoV-1 transmission may differ from SARS-CoV-2. Randomized controlled trials have not been conducted.

Symptomatic people should follow public health guidance and self-isolate. The point of community mask wearing is to prevent presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission. Although asymptomatic transmission undoubtedly occurs,59, 60, 61, 62 the proportion of transmission that occurs from asymptomatic individuals is the subject of controversy.63 , 64 However, evidence from transmission pairs suggests that in individuals who will eventually develop symptoms, peak infectivity may occur before the onset of symptoms and that the highest levels of viral shedding may occur 2 to 3 days before the appearance of symptoms and 1 day after.65 Data on viral load in the days after symptom onset are congruent with this hypothesis,66 and presymptomatic transmission has been documented.62 , 67 Modeling studies reveal that face mask use depresses the effective basic reproductive rate over a range of plausible values for mask use and cloth mask effectiveness and that in conjunction with periods of lockdown, even 50% adherence to a 50%-effective cloth mask dramatically alters the total number of individuals affected.68

What Materials and Designs Should Be Used? An Evidence-Informed Cloth Mask

A pleated mask design based on the common pleated design for ASTM International level 1 masks results in a mask with subjectively good fit that is relatively simple to make. Paper fasteners, florists’ or electricians’ wire, or pipe cleaners can be inserted across the top to improve fit at the nose. Although data are not available that conform with any modern standard method, from the studies available, cotton, muslin (a type of unfinished cotton), and flannel are the best supported and are our suggestions for an evidence-informed cloth mask. Successful masks have used muslin at a TPI of approximately 100 in 3 to 4 layers (4-layer muslin28 or a muslin-flannel-muslin sandwich17), tea towels (also known as dish towels)—studied as 1 layer32 and 2 layers expected to be better12 , 14 , 15 , 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 , 27 , 34—and good-quality cotton T-shirts in 2 layers14 , 46 , 49; in flat cloth experiments, linen tea towel in 2 layers14 , 46 cotton 600 TPI in 2 layers23 or cotton 600 TPI with flannel 90 TPI23 performed well. (Two-layer cotton 80 TPI did not perform well.23) Multiple layers should be used, at least 2 and preferably 3 or 4. With fabric that stretches, such as T-shirt fabric, it may be important to use a design with edge stitching to prevent transmission of tension to the cloth, which will increase the size of gaps in the material and affect filtration. There is a trade-off with increased layers: they provide increased filtration efficiency but also increase the resistance to breathing, which increases the work of breathing and may lead to discomfort and even to reduced adherence. Increased resistance with increased layers also leads to increased edge leak, decreasing the efficiency of the mask. People making masks for sale should specify the materials (composition, weave, weight, thread count) for each layer and the number of layers (eg, cotton 100%, plain weave, 150 g/m2, 150 TPI; 3 layers). People making their own masks or choosing a mask should consider these same factors and also their planned activities while wearing a mask. It might be sensible, for example, to choose a higher number of layers for quietly sitting at a desk in a shared workspace for the duration of a working day than for grocery shopping in a ventilated environment with physical distancing. Based on expert opinion, the WHO guidance published June 5, 2020,9 recommends a 3-layer mask, the outer layer and middle layers hydrophobic (eg, polypropylene, polyester, and their blends) and the inner layer hydrophilic (eg, cotton or cotton blends).

Our previously mentioned recommendations for materials are the same if using a bandana or scarf-type design, although we would anticipate that it would be less efficient. Optimally, this mask will include a prefolded shape and a clear differentiation of outside and inside, such as the multilayered suggestion demonstrated on YouTube.69 Evidence on household filters is limited. The one study of tissue paper and paper towel masks did not report high efficiencies35; we believe that a third or fourth layer of cloth is preferable to a disposable filter. Information on materials, designs, and correct use intended for the general public and for mask manufacturers can be found at clothmasks.ca. We will update this site as new information is published.

What Are the Research Priorities? An Evidence-Based Cloth Mask

Reproducibly described cloth and cloth masks should be tested in aerosol laboratories. The effects of activity, time, and moisture18 , 24 on effectiveness should be studied. The trade-off with higher thread counts and additional layers between increased protection on the one hand and decreased tolerability and increased leak on the other should be explicitly explored.70 Women, children, people with facial hair, people who wear turbans or hijabs, people who are deaf and people who wear glasses require special consideration. Optimal methods of laundering (home and industrial) and the effect of laundering on mask properties should be studied.

Human trials should focus on best-performing cloth masks, should include health care workers, other essential workers, and clients of essential services who can tolerate mask wearing, and should study both inward and outward protection. Considerations are multifaceted—educational interventions, measures of unintended consequences (eg, incorrect mask use, complacency about physical distancing and hand hygiene, mitigation of effects on people who do not hear well), and the impact of adherence on outcomes.

If reproducible designs of cloth masks that meet ASTM International standards can be identified, it will have direct and immediate impact in low- and middle-income countries. Widespread adoption in any setting, including high-income countries, of reusable evidence-based cloth masks that meet the standards of PPE would reduce the environmental impact of PPE and mitigate supply problems in this and future pandemics.

Standards for cloth masks have been developed by the French standardization association Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR): testing flat cloth using 3-μm particles, 70% to less than 90% filtration efficiency is designated as category 2 (for use by the general public in a group of mask wearers), and 90% to less than 95% is designated as category 1 (for use by non–health care professionals in contact with the public, eg, police).71, 72, 73 At the time of this writing, a database of more than 1200 tested mask material combinations (many of them including nonwoven synthetic materials such spunbond and meltbond that are used in formal PPE) has been compiled.73 , 74

Businesses and academics in textiles, design, and fashion are critical in embracing evolving information on evidence-informed and evidence-based masks and in using their specific knowledge and skills to create a variety of masks that are not only functional but comfortable and stylish to maximize the acceptability of mask wearing, particularly for young people.

Conclusion

Cloth masks can offer substantial filtration, in some cases equivalent to some medical masks. This knowledge can be used to create evidence-informed cloth masks to mitigate transmissibility of viruses such as COVID-19. Aerosol laboratory testing of these masks may lead to the design of evidence-based cloth masks, reproducibly described so as to be manufactured in diverse settings. Currently, no direct data with clinically important outcomes are available.

Advocating for the public to wear cloth masks shifts the cost of a public health intervention from society to the individual. In low-resource areas and for people living in poverty, this burden may be unacceptable and could be mitigated by public health interventions with local manufacture and distribution of evidence-informed and evidence-based cloth masks.

Acknowledgments

This work was created, in part, on the traditional territory shared between the Haudenosaunee confederacy and the Anishinaabe nations, which was acknowledged in the Dish With One Spoon wampum belt.

We thank Melanie Chiarot, librarian, for her assistance in retrieving articles during a holiday period and Robinson Healthcare Limited in the United Kingdom, who volunteered details of materials and methods for and photographs of the commercial 4-layer muslin mask. We thank the authors who responded promptly for additional details of their studies and the editors and anonymous reviewers whose suggestions greatly improved this work. We thank Dr Zain Chagla, infectious diseases consultant, McMaster University, for his peer review of the clothmasks.ca website. We dedicate this article to Esta H. McNett and Charlotte Johnson, nurses who made important contributions to the field of mask design but who were not acknowledged as authors in the manuscripts that included descriptions of their work. We recognize the animals that suffered and died.

Author contributions: The concept for the manuscript originated with Drs Clase, Jardine, Mann, Pecoits-Filho, Winkelmayer, and Carrero. Dr Clase and Mr Fu performed the original literature review, and Dr Clase wrote the first draft. Mr Fu, Mr Ashur, Ms Clase, Dr Kansiime, and Dr Joseph reviewed citations and performed data extraction. Dr Carrero and Mr Fu collated discrepancies and, with Dr Clase, resolved them by consensus. Mr Fu performed statistical analysis on reported data and created graphs and tables. Prof Dolovich provided input on aerosol science and Dr Beale on virology and relevance to COVID-19. All authors contributed references and important revisions of content and meaning. Dr Clase is the guarantor for the work.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Clase has received consultancy fees from Amgen Inc, Astellas Pharma Inc, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Johnson & Johnson Services, Inc, LEO Pharma Inc, and Pfizer Inc and speaker honoraria from Sanofi. Dr Jardine is responsible for research projects that have received unrestricted funding from Gambro, Baxter, CSL Limited, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; has served on advisory boards sponsored by Akebia Therapeutics, Inc, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, and Vifor Pharma Management Ltd.; serves on steering committees for trials sponsored by Janssen and CSL; and has spoken at scientific meetings sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Amgen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, and Vifor Pharma Management Ltd. (all funds paid to her institution). Dr Mann has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Fresenius Medical Care, MEDICE, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Novo Nordisk A/S, and Roche Ltd; has received research support from Celgene Corporation, Novo Nordisk A/S, Roche Ltd, and Sandoz International GmbH; and has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Celgene Corporation, and Novo Nordisk A/S. Dr Pecoits-Filho has received consultancy fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Inc, AstraZeneca, Fresenius Medical Care, and Novo Nordisk A/S; has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk A/S; and has received research support from Fresenius Medical Care. Dr Winkelmayer has received consultancy fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Inc, Amgen Inc, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Daichi-Sankyo Company, Limited, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Merck & Co, Inc, Relypsa Inc, Vifor Pharma Management Ltd, and Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma and speaker honoraria from FibroGen, Inc. Dr Carrero has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca and Baxter; has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca and Vifor Pharma Management Ltd; and has received research support from the AstraZeneca, Vifor Pharma Management Ltd., and Astellas Pharma Inc. The other authors report no competing interests.

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 dashboard. Johns Hopkins University website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organisation Advice on the use of masks the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-2019-ncov.pdf Published January 29, 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 6 April 2020. World Health Organization website. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331693

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Considerations for wearing masks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html Updated August 7, 2020.

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health Communication: use of non-medical masks (or facial coverings) by the public. Public Health Agency of Canada website. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2020/04/ccmoh-communication-use-of-non-medical-masks-or-facial-coverings-by-the-public.html Updated April 7, 2020.

- 6.Feng S., Shen C., Xia N., Song W., Fan M., Cowling B.J. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):434–436. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahase E. Covid-19: what is the evidence for cloth masks? BMJ. 2020;369:m1422. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nippon Communications Foundation Japan govt to give 2 masks to every household over virus. Nippon.com website. https://www.nippon.com/en/news/yjj2020040101147/japan-govt-to-give-2-masks-to-every-household-over-virus.html Published April 1, 2020.

- 9.World Health Organization Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak Published June 5, 2020.

- 10.World Health Organization Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide Published March 3, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 11.Capps J.A. Measures for the prevention and control of respiratory infections in military camps. JAMA. 1918;71(6):448–451. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper D.W., Hinds W.C., Price J.M., Weker R., Yee H.S. Common materials for emergency respiratory protection: leakage tests with a manikin. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1983;44(10):720–726. doi: 10.1080/15298668391405634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dato V.M., Hostler D., Hahn M.E. Simple respiratory mask [letter] Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(6):1033–1034. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies A., Thompson K.-A., Giri K., Kafatos G., Walker J., Bennett A. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(4):413–418. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doust B.C., Lyon A.B. Face masks in infections of the respiratory tract. JAMA. 1918;71(15):1216–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuhashi M. A study on the microbial filtration efficiency of surgical face masks—with special reference to the non-woven fabric mask. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ. 1978;25(1):7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene V.W., Vesley D. Method for evaluating effectiveness of surgical masks. J Bacteriol. 1962;83(3):663–667. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.3.663-667.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyton H.G., Decker H.M., Anton G.T. Emergency respiratory protection against radiological and biological aerosols. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1959;20(2):91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haller D.A., Colwell R.C. The protective qualities of the gauze face mask: experimental studies. JAMA. 1918;71(15):1213–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang J.Y., Kim S.W. Evaluation of filtration performance efficiency of commercial cloth masks. J Environ Health Sci. 2015;41(3):203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung H., Kim J.K., Lee S.A. Comparison of filtration efficiency and pressure drop in anti-yellow sand masks, quarantine masks, medical masks, general masks, and handkerchiefs. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2014;14(3):991–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellogg W.H., Macmillan G. An experimental study of the efficacy of gauze face masks. Am J Public Health (N Y) 1920;10(1):34–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.10.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konda A., Prakash A., Moss G.A., Schmoldt M., Grant G.D., Guha S. Aerosol filtration efficiency of common fabrics used in respiratory cloth masks [published correction appears online ahead of print in ACS Nano, June 18, 2020; doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c04676] ACS Nano. 2020;14(5):6339–6347. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leete H.M. Some experiments on masks. Lancet. 1919;193:392–393. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lurie M.B., Abramson S. The efficiency of gauze masks in the protection of rabbits against the inhalation of droplet nuclei of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Tuberc. 1949;59(1):1–9. doi: 10.1164/art.1949.59.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacIntyre C.R., Seale H., Dung T.C. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006577. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paine C.G. The aetiology of puerperal infection. BMJ. 1935;1(3866):243–246. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3866.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quesnel L.B. The efficiency of surgical masks of varying design and composition. Br J Surg. 1975;62(12):936–940. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800621203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rengasamy S., Eimer B., Shaffer R.E. Simple respiratory protection—evaluation of the filtration performance of cloth masks and common fabric materials against 20-1000 nm size particles. Ann Occup Hyg. 2010;54(7):789–798. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/meq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shakya K.M., Noyes A., Kallin R., Peltier R.E. Evaluating the efficacy of cloth facemasks in reducing particulate matter exposure. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27(3):352–357. doi: 10.1038/jes.2016.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shooter R.A., Smith M.A., Hunter C.J. A study of surgical masks. Br, J Surg. 1959;47:246–249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004720312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Sande M., Teunis P., Sabel R. Professional and home-made face masks reduce exposure to respiratory infections among the general population. PloS One. 2008;3(7):e2618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver G.H. The value of the face mask and other measures in prevention of diphtheria, meningitis, pneumonia, etc. JAMA. 1918;70(2):76–78. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver G.H. Droplet infection and its prevention by the face mask. J Infect Dis. 1919;24(3):218–230. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao M., Liao L., Xiao W. Household materials selection for homemade cloth face coverings and their filtration efficiency enhancement with triboelectric charging. Nano Lett. 2020;20(7):5544–5552. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ASTM International ASTM Reading Room. COVID-19 related standards: masks. https://www.astm.org/READINGLIBRARY/VIEW/PHMSA.html

- 37.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) NIOSH guide to the selection and use of particulate respirators: certified under 42 CFR 84. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication 96-101. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/96-101/default.html Published January 1996. Reviewed June 6, 2014.

- 38.Occupational Safety and Health Administration Assigned protection factors for the revised respiratory protection standard. Occupational Safety and Health Administration website. https://www.osha.gov/Publications/3352-APF-respirators.pdf Published 2009.

- 39.Canadian Standards Association CAN/CSA Z94.4-2018: selection, use, and care of respirators, American National Standrads Institute website. https://webstore.ansi.org/Standards/CSA/CSAZ942018?gclid=Cj0KCQjwuJz3BRDTARIsAMg-HxX4F2MYi5rxnJQXstCHVUXJz-2ugsaSNEoW3A_douYB5OvGwd23Xm0aApG8EALw_wcB Published 2018.

- 40.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P. Electron microscopy of SARS-CoV-2: a challenging task [letter] Lancet. 2020;395(10238):e100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.SEMLab, Inc Fiber analysis. SEMLab website. https://www.semlab.com/services/materials-analysis/fiberanalysis/

- 42.Verma D. Effectiveness of DIY masks: how do they work? Nanoscience Instruments website. https://www.nanoscience.com/applications/materials-science/effectiveness-of-diy-masks-how-do-they-work/

- 43.Laube B.L., Dolovich M.B. In: Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Adkinson N.F., Bochner B.S., Burks A.W., editors. Elsevier/Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2014. Aerosols and aerosol drug delivery systems; pp. 1066–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han Z.Y., Weng W.G., Huang Q.Y. Characterizations of particle size distribution of the droplets exhaled by sneeze. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10(88):20130560. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.VanSciver M., Miller S., Hertzberg J. Particle image velocimetry of human cough. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2011;45(3):415–422. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies A., Thompson K.-A., Giri K., Kafatos G., Walker J.T., Bennett A.M. Frequently asked questions - homemade facemasks study. ResearchGate website. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340253593_Frequently_asked_questions_-_homemade_facemasks_studypdf

- 47.McKhann C.F., Steeger A., Long A.P. Hospital infection: a survey of problem. Am J Dis Child. 1938;55(3):579–599. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson M.E., Gillespie W.A. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus by nurses. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1958;75(2):351–355. doi: 10.1002/path.1700750213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies A., Thompson K.-A., Giri K., Kafatos G., Walker J.T., Bennett A.M. Facemask instructions COVID-19.doc.ResearchGate website. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340023785_facemask_instructions_COVID-19doc Published March 2020.

- 50.Dyer E. Some health experts questioning advice against wider use of masks to slow spread of COVID-19. CBC website. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/covid-19-pandemic-coronavirus-masks-1.5515526 Published March 31, 2020.

- 51.Wheelahan D. Cloth masks: dangerous to your health? ScienceDaily websiste. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/04/150422121724.htm Published April 22, 2015.

- 52.Greenhalgh T., Schmid M.B., Czypionka T., Bassler D., Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clase C.M., Fu E.L., Joseph M. Cloth masks may prevent transmission of COVID-19: an evidence-based, risk-based approach. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2567 [published online ahead of print May 22, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Chu D.K., Akl E.A., Duda S., Solo K., Yaacoub S., Schünemann H.J. COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Review Group Effort (SURGE) study authors. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuan P.A., Horby P., Dinh P.N., WHO SARS Investigation Team in Vietnam SARS transmission in Vietnam outside of the health-care setting. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(3):392–401. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lau J.T., Lau M., Kim J.H., Tsui H.-Y., Tsang T., Wong T.W. Probable secondary infections in households of SARS patients in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):235–243. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu J., Xu F., Zhou W. Risk factors for SARS among persons without known contact with SARS patients, Beijing, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):210–216. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill A.B. The environment and disease: association or causation? J R Soc Med. 2015;108(1):32–37. doi: 10.1177/0141076814562718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan X., Chen D., Xia Y. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infecti Dis. 2020;20(4):410–411. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kimball A., Hatfield K.M., Arons M. Public Health – Seattle & King County; CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377–381. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller A. WHO backtracks on claim that asymptomatic spread of COVID-19 is 'very rare.' CBC website. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/who-covid-19-asymptomatic-spread-1.5604353 Published June 2, 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 64.Li R., Pei S., Chen B. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368(6490):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wei W.E., Li Z., Chiew C.J., Yong S.E., Toh M.P., Lee V.J. Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 - Singapore, January 23-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stutt R.O.J.H., Retkute R., Bradley M., Gilligan C.A., Colvin J. A modelling framework to assess the likely effectiveness of facemasks in combination with ‘lock-down’ in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc R Soc A. 2020:20200376. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2020.0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Make a bandana face mask in under 1 minute with just two materials. YouTube website. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TasM4uRj74 Published April 15, 2020.

- 70.Podgórski A., Balazy A., Gradoń L. Application of nanofibers to improve the filtration efficiency of the most penetrating aerosol particles in fibrous filters. Chem Eng Sci. 2006;61:6804–6815. [Google Scholar]

- 71.EuraMaterials, Institut Français du Textile et de L'Habillement Techtera. Actualisation de la base selon la note interministerielle du 29 Mars 2020 [Database update in keeping with the interministerial note of March 29, 2020]. EuraMaterials website. https://euramaterials.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/base-de-donnees-matieres-resultats-dga-maj-26052020.pdf

- 72.Euramaterials, Institut Français du Textile et de L'Habillement Techtera. Note d'information à destination des industriels. Base de données du groupe matière: masques à Usage Non Sanitaire (UNS) [Information note for manufacturers. Material group database: non-medical masks]. Euramaterials website. https://euramaterials.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2020-04-28-Note-dinformation-BdD-mati%C3%A8res.pdf Published April 28, 2020.