Abstract

Energy drinks (ED) are becoming increasingly popular, but little has been reported about their stomach effects. To our knowledge, there is no literature suggesting an association with the development of atrophic gastritis (AG) or gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM). AG and GIM have been associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. Reversal of these lesions has shown to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer but has only been studied to eradicate Helicobacter pylori. This case describes a female who consumed high amounts of ED and was subsequently diagnosed with AG and GIM. Interestingly, the pathologies resolved upon cessation of ED.

Keywords: energy drinks, atrophic gastritis, gastric intestinal metaplasia, gastric cancer

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer globally and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality. Atrophic gastritis (AG) and Gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) have an increased risk of developing into gastric cancer by following the gastric carcinogenesis pathways [1]. Reversal of AG and GIM has shown to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer. However, it has only been studied to eradicate the most common cause, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) [2-3]. We present AG and GIM's case involving a 34-year-old Hispanic female regularly consuming energy drinks (ED) since 2003 with subsequent reversal of AG and GIM upon cessation of ED. This is the first case report describing ED as a possible risk factor for AG and GIM development.

Case presentation

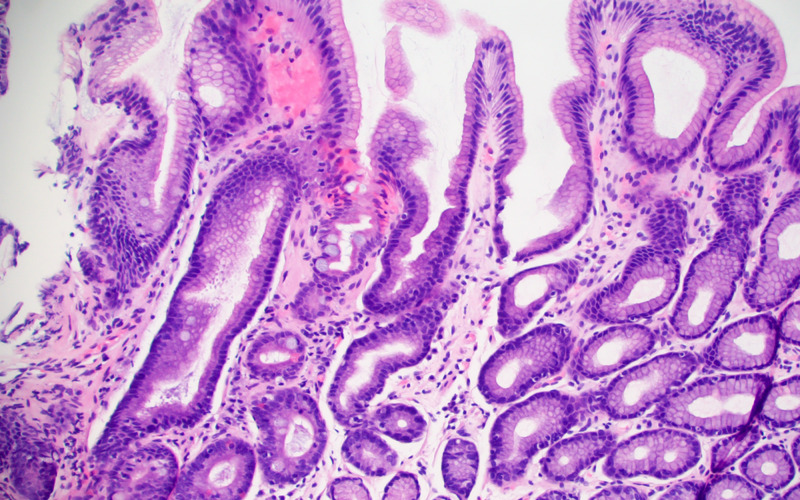

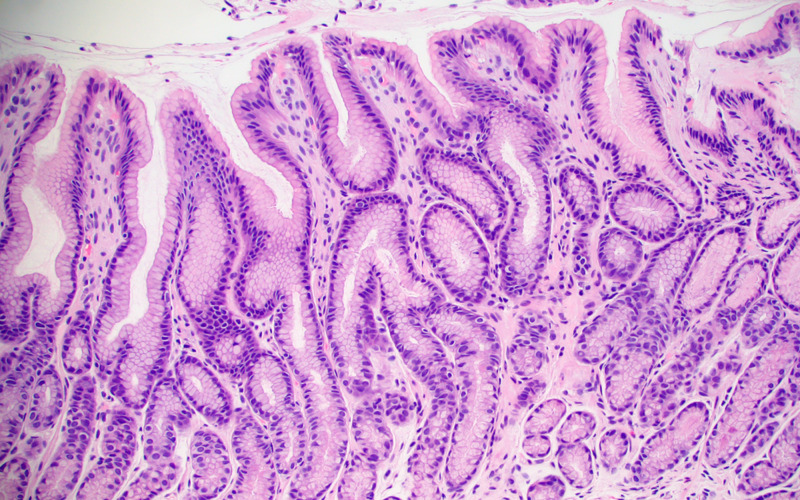

A 34-year-old Hispanic female presented with two different types of abdomen pain for more than a year. The first pain was in the epigastric area and was associated with dyspepsia. The second one was in the right upper quadrant and was colicky. No abnormality of the gallbladder or the biliary tract was found when the patient underwent abdominal ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). On an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), the stomach appeared atrophic raising suspicion of intestinal metaplasia. Biopsies taken from the stomach revealed AG and focal antral intestinal metaplasia (Figure 1). H. pylori immunostaining was negative. The patient had normal levels of iron, vitamin B12, methylmalonic acid, gastrin, intrinsic factor blocking antibody, and parietal cell antibody. The patient reportedly consumed alcohol occasionally a few times per year and had never smoked in her lifetime. On further questioning, she reported a regular intake of 1-2 ED/day, namely Red Bull® and Monster Energy® for the past 15 years. The patient was hence advised to stop consuming ED, and her dyspepsia was treated with intermittent proton pump inhibitors for the next two years. Surveillance EGD 2 years after the initial diagnosis revealed normal-appearing gastric mucosa. Gastric topographic mapping biopsies using Sydney protocol revealed normal mucosa (Figure 2). These findings implicated the reversal of AG and GIM upon withdrawal of ED.

Figure 1. Antral mucosa with changes of reactive gastropathy and atrophy. Intestinal metaplasia, characterized by goblet cells, is seen within the mid-left portion of the image.

Figure 2. Normal antral mucosa. No reactive changes or intestinal metaplasia present.

Discussion

In the study conducted by Sonnenberg A et al. using biopsies from upper endoscopies between 2008 and 2013, the overall prevalence of GIM was 4.9% [4]. Since chronic AG is frequently asymptomatic, its prevalence is not known [5] Chronic H. pylori infection is the most common etiologic factor identified in the development of AG and GIM, followed by Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis (AMAG). The worldwide prevalence of H. pylori is approximately 50%, and approximately 35%-40% in the United States [6]. In a study done by Shiota S et al. at VA Medical Center, it was found that out of all patients with gastritis, approximately 18% of the patients had H. pylori-negative gastritis [7].

On the other hand, the prevalence of AMAG is only 2% in the general population [8]. Therefore, the prevalence of H. pylori-negative gastritis far outnumbers AMAG, making us think that there must be other causes than the two established ones. According to recent studies, factors like smoking and diet play an important role in AG's pathogenesis. Smoking has been shown to promote AG and GIM, but the relationship has been established only in H. pylori-positive patients [9]. High salt intake has also shown to be associated with increased risk of AG [10].

On the other hand, moderate alcohol intake has been inversely associated with AG suggested by the facilitation of elimination of H. pylori through the antibacterial action of alcohol [11]. Our patient has never smoked in her lifetime and consumes a low salt diet, ruling out the role of smoking and high salt diet in the development of her gastric pathologies. However, her long history of regular consumption of ED suggests that these could be another dietary factor involved in AG and GIM's pathogenesis.

A study performed to examine the effects of Power Horse® ED on Albino rats' stomach, and pancreas showed evidence of Power Horse-induced oxidant-antioxidant imbalance, degenerative changes, and increased apoptosis in the fundic mucosa of the stomach of the rats [12]. The fundic mucosa showed reduced parietal cells and gastrin hormone expression compared to the control group [12]. Another study done by Raeesa A. Mohamed et al. on adult Wistar rats demonstrated marked depletion of mucus secretion in the mucosae of stomach and duodenum of Red Bull group with a significant increase of apoptotic cells in the mucosae of stomach and duodenum [13]. Unfortunately, no data is describing the effects of ED on the mucosa of the human stomach. The only gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects reported in humans include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea [14].

All ED share ingredients constitute caffeine, carbonated water, glucose, sucrose, citric acid, sodium citrate, taurine, B vitamins (B2, B3, B5, B6, B12) natural or artificial flavours. Power Horse also contains inositol and glucuronolactone, both found in Monster ED but not in Red Bull. Red bull differs from Power horse as it contains acidity regulators such as Sodium Bicarbonate and magnesium carbonate. On the other hand, Monster ED differs from Power horse as the former contains additional amino acids (L-carnitine), preservatives (sorbic acid, benzoic acid), plant extracts (guarana seed extract, Panax ginseng root extract) and sucralose. GI side effects described with caffeine include increased gastric acid production, gastro-oesophagal reflux, decreased absorption and impaired motility [15], but data regarding these are conflicting and inconclusive. Several studies have also shown that these side effects might be due to the other ingredients present in caffeine-containing drinks rather than caffeine itself [16]. Sodium Citrate ingestion has been shown to cause nausea, bloating, vomiting and diarrhoea [17]. The rest of the ingredients, individually, have not been reported to cause any GI adverse effects. None of the ingredients, however, have been associated with the development of AG or GIM.

The reversibility of AG and GIM, till now, has been documented only with the eradication of H. pylori [3]. Substances like muscovite, folic acid and gefarnate may also be useful in reversing AG and GIM [18-20]. Nonetheless, there is no known literature suggesting reversibility of the lesions with the cessation of energy drinks.

Conclusions

Energy drink discontinuation in our patient led to the reversal of her gastric pathology showing environmental factors could play a critical role in gastric dysplasia. Prompt recognition and lifestyle modification may prevent AG, GIM, and subsequently gastric cancer. Hence we need more data about the effects of ED to know for possible reversal of AG and GIM to minimize symptoms, surveillance, and risk of gastric cancer. Additional research is also warranted on what particular ingredient(s) in ED, at what concentration, and what duration, could lead to the development of the observed findings.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Gastric atrophy, metaplasia, and dysplasia: a clinical perspective. Kapadia CR. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:29–62. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200305001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lee YC, Chiang TH, Chou CK, Tu YK, Liao WC, Wu MS, Graham DY. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113–1124. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reversibility of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia after Helicobacter pylori eradication - a prospective study for up to 10 years. Hwang YJ, Kim N, Lee HS, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:380–390. doi: 10.1111/apt.14424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Changes in the gastric mucosa with aging. Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2276–2281. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical manifestations of chronic atrophic gastritis. Rodriguez-Castro KI, Franceschi M, Noto A, et al. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:88–92. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i8-S.7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helicobacter pylori: ulcers and more: the beginning of an era. Lacy BE, Rosemore J. J Nutr. 2001;131:2789–2793. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2789S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical manifestations of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis. Shiota S, Thrift AP, Green L, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cigarette smoking promotes atrophic gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-positive subjects. Nakamura M, Haruma K, Kamada T, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:675–681. doi: 10.1023/a:1017901110580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.High salt intake is associated with atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia. Song JH, Kim YS, Heo NJ, et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1133–1138. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alcohol consumption and chronic atrophic gastritis: population-based study among 9,444 older adults from Germany. Gao L, Weck MN, Stegmaier C, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2918–2922. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Impact of an energy drink on the structure of stomach and pancreas of albino rat: can omega-3 provide a protection? Ayuob N, ElBeshbeishy R. PLoS One. 2016;11:149191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Energy drinks induce adverse histopathological changes in gastric and duodenal mucosae of rats. Mohamed RA, Ahmed AM, Al-Matrafi TA, et al. Int J Advances Appl Sci. 2018;5:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adverse effects of caffeinated energy drinks among youth and young adults in Canada: a web-based survey. Hammond D, Reid JL, Zukowski S. CMAJ Open. 2018;6:19. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Methodological and metabolic considerations in the study of caffeine-containing energy drinks. Shearer J. Nutrition Reviews. 2014;72:137–145. doi: 10.1111/nure.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The influence of coffee and caffeine on gastrin and acid secretion in man [Article in German] Börger HW, Schafmayer A, Arnold R, Becker HD, Creutzfeldt W. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1253714/ Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1976;101:455–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Induced alkalosis and gastrointestinal symptoms after sodium citrate ingestion: a dose-response investigation. Urwin CS, Dwyer DB, Carr AJ. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2016;26:542–548. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2015-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muscovite reverses gastric gland atrophy and intestinal metaplasia by promoting cell proliferation in rats with atrophic gastritis. Wang LJ, Zhou QY, Chen Y, et al. Digestion. 2009;79:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000207489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The effect of folic acid on the development of stomach and other gastrointestinal cancers. Zhu S, Mason J, Shi Y, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12667380/#:~:text=Conclusions%3A%20This%20trial%20revealed%20the,or%20reversing%20the%20precancerous%20lesions. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evaluation of efficacy of gefarnate in treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia. Lai Y, Xu P, Li Q, Ren D, Sun X, Xu K, Huang J. Chinese J Gastroenterol. 2013;18:473–476. [Google Scholar]