Abstract

A 64-year-old man presented with severe myocarditis 6 weeks after an initial almost asymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV2) infection. He was found to have a persistent positive swab. Mechanisms explaining myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 remains unclear, but this case suggests that severe acute myocarditis can develop in the late phase of COVID-19 infection, even after a symptom-free interval.

Résumé

Un homme de 64 ans a présenté une myocardite grave six semaines après avoir été infecté par le coronavirus du syndrome respiratoire aigu sévère 2 (SRAS-CoV-2), qui n’avait provoqué pratiquement aucun symptôme. Le patient obtenait toujours un résultat positif au test de dépistage du SRAS-CoV-2. On ne connaît pas bien les mécanismes à l’origine des lésions myocardiques observées chez des patients atteints de COVID-19, mais ce cas montre qu’il est possible qu’une myocardite aiguë grave survienne aux stades avancés d’une infection par le SRAS-CoV-2, même après une période sans symptômes.

COVID-19 can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations. Data about primary myocardial involvement are scarce and have generally been described in the early phase of infection.1 We report a case of late acute myocarditis in the setting of persistent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Case

A 64-year-old man, known for isolated pulmonary sarcoidosis and epilepsy, presented to our hospital with fever and cough on March 14, 2020. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was made based on a positive nasopharyngeal swab. He did not require hospitalization, and symptoms regressed spontaneously within 48 hours. Six weeks later, he presented again to our hospital with chest pain and dyspnea. On admission, he had high-grade fever (39.3 °C [102,74 °F]) without hemodynamic compromise. Laboratory tests revealed elevated high-sensitivity troponin T at 263 ng/L, leukocytosis (white blood cell [WBC]: 18.7 G/L) and elevated D-Dimers at 1210 ng/mL (Supplemental Table S1). The electrocardiogram was unremarkable as was the chest x-ray film. A thoracic computed tomography scan found minimal ground-glass opacities in the right lung, raising the suspicion of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. This latter was confirmed on repeated positive nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, although at a lower viral count.

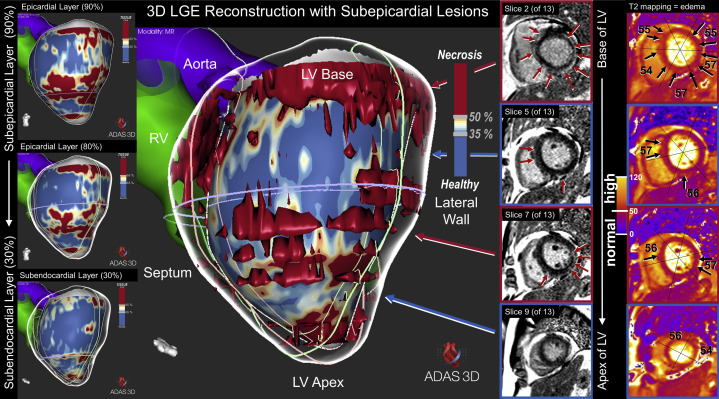

An urgent cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) scan revealed a reduced left-ventricular (LV) systolic function (LV ejection fraction [LVEF]: 42%) with mild hypokinesia of the lateral wall. T2-mapping sequences showed myocardial edema (segmental T2 = 55-57 ms). Free-breathing motion-corrected phase-sensitive inversion recovery acquisitions were performed and demonstrated subepicardial late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in the anterior interventricular septum and in the inferior and inferolateral walls (Fig. 1 ). Based on CMR findings, the diagnosis of acute myocarditis was established. Shortly after the CMR examination, the patient’s respiratory condition worsened, with development of hemodynamic instability, and he was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he required intubation and catecholamine support.

Figure 1.

CMR examination showing 3D reconstructions of inflammatory lesion distribution (red areas, central panel). On the left, extensive inflammatory lesions (red areas) are demonstrated at the subepicardial layer (top), fading toward the subendocardial layer (bottom), which is the typical pattern for myocarditis. To the right of the central panel, the raw images of late gadolinium enhancement (arrows) are shown again, illustrating the subepicardial distribution. On the right, T2 mapping shows increased values in several segments, indicating the presence of edema (numbers are T2 values in ms).

Laboratory analysis showed a severe inflammatory response with (WBC: 33 G/L, C-reactive protein: 466 mg/L, and procalcitonin 22 ng/mL). Cardiac biomarkers increased markedly, with a peak value of troponin of 1843 ng/L. Chest x-ray film revealed new bilateral reticulation and ill-defined opacities, suggesting interstitial edema. Empirical antimicrobial treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam was started.

Following admission to the ICU, the patient’s condition rapidly improved, with successful extubation after 24 hours. Echocardiography performed 72 hours after the CMR showed stable LVEF at 47%. Considering this favourable evolution, endomyocardial biopsies were not performed. Extensive infectious analysis and autoimmune screening results were negative, except for the persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection (Supplemental Table S2 ). Coronary computed tomography angiography allowed exclusion of significant epicardial coronary stenoses. The patient was discharged on day 12, with almost complete recovery.

Discussion

Herein, we describe a case of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting with acute severe myocarditis. Indeed, even if a reinfection cannot be completely excluded, the decreasing viral count at the time of second presentation—and the fact that the result of a nasopharyngeal swab done 5 days after hospitalization was found to be negative—militates strongly in favour of a persistent infection.

The actual mechanisms explaining myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 remains to be elucidated. Some case series have shown that cardiac complications, including heart failure, arrhythmias, and myocardial infarction are not uncommon,2 but endomyocardial biopsies have been performed in few cases, showing mainly lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates,3 in line with the overwhelming inflammatory response known to be triggered by the virus.

This report also highlights the role of CMR as the gold standard imaging modality in case of myocarditis.4 In this situation, the use of a modified novel free-breathing motion corrected LGE technique5 during administration of gadobutrol offered the possibility to establish the diagnosis of myocarditis in a severely dyspneic patient unable to hold his breath and to exclude myocardial infarction.

Finally, this patient developed severe cardiac involvement after a 6-week asymptomatic phase, highlighting the importance of clinical surveillance in case of apparently benign SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indeed, because of the scarce data available, the delay between infection and presentation of cardiac symptoms is still uncertain. It also raises the question of whether repeated tests should be performed during the convalescence phase.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 infection can be persistent over a 6-week asymptomatic period and can present with late severe clinical manifestations, including acute myocarditis with hemodynamic instability. Additional data are needed regarding adequate monitoring during the convalescent period of COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff members who are working hard in our institution during this difficult period. The authors also thank Rosa M. Figueras i Ventura, PhD, for the 3D reconstructions, and ADAS 3D Medical, Barcelona, Spain, for providing the software.

Funding Sources

The authors report no funding sources relevant to the contents of this paper.

Disclosures

Dr Schwitter receives research support from Bayer Healthcare, Switzerland. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 1326.e7 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the Canadian Journal of Cardiology at www.onlinecjc.ca and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.06.005.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Hu H., Ma F., Wei X., Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin [epub ahead of print] Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sala S., Peretto G., Gramegna M. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1861–1862. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesbroek P.S., Hirsch A., Zweerink A. Additional diagnostic value of CMR to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) position statement criteria in a large clinical population of patients with suspected myocarditis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1397–1407. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Captur G., Lobascio I., Ye Y. Motion-corrected free-breathing LGE delivers high quality imaging and reduces scan time by half: an independent validation study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;35:1893–1901. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01620-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.