Abstract

Objective

To review the virology, immunology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment of the following 3 major zoonotic coronavirus epidemics: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Data Sources

Published literature obtained through PubMed database searches and reports from national and international public health agencies.

Study Selections

Studies relevant to the basic science, epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and treatment of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, with a focus on patients with asthma, allergy, and primary immunodeficiency.

Results

Although SARS and MERS each caused less than a thousand deaths, COVID-19 has caused a worldwide pandemic with nearly 1 million deaths. Diagnosing COVID-19 relies on nucleic acid amplification tests, and infection has broad clinical manifestations that can affect almost every organ system. Asthma and atopy do not seem to predispose patients to COVID-19 infection, but their effects on COVID-19 clinical outcomes remain mixed and inconclusive. It is recommended that effective therapies, including inhaled corticosteroids and biologic therapy, be continued to maintain disease control. There are no reports of COVID-19 among patients with primary innate and T-cell deficiencies. The presentation of COVID-19 among patients with primary antibody deficiencies is variable, with some experiencing mild clinical courses, whereas others experiencing a fatal disease. The landscape of treatment for COVID-19 is rapidly evolving, with both antivirals and immunomodulators demonstrating efficacy.

Conclusion

Further data are needed to better understand the role of asthma, allergy, and primary immunodeficiency on COVID-19 infection and outcomes.

Key Messages.

-

•

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are zoonotic epidemics caused by members of the Coronaviridae family of enveloped, single-stranded, RNA viruses.

-

•

The diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and COVID-19 relies on nucleic acid amplification tests, which are highly specific, but their sensitivity depends on many clinical factors, including the timing from symptom onset and sample type relative to disease.

-

•

COVID-19 has broad clinical manifestations and can affect almost every organ system in the body.

-

•

Although asthma and atopy do not seem to predispose patients to COVID-19 infection, their effects on COVID-19 clinical outcomes remain uncertain. It is recommended that effective therapies, including inhaled corticosteroids and biologic therapy, be continued to maintain disease control.

-

•

There are no reports of COVID-19 among patients with primary innate and T-cell deficiencies. The presentation of COVID-19 among patients with primary antibody deficiencies is variable, with some experiencing mild clinical courses and others experiencing fatal infection despite multimodal therapy.

-

•

The landscape of treatment for COVID-19 is rapidly evolving. The main classes of therapy include antivirals and immunomodulators, and there are drugs from each category demonstrating efficacy in the management of COVID-19.

Instructions.

Credit can now be obtained, free for a limited time, by reading the review article and completing all activity components. Please note the instructions listed below:

-

•

Review the target audience, learning objectives and all disclosures.

-

•

Complete the pre-test.

-

•

Read the article and reflect on all content as to how it may be applicable to your practice.

-

•

Complete the post-test/evaluation and claim credit earned. At this time, physicians will have earned up to 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM . Minimum passing score on the post-test is 70%.

Overall Purpose

Participants will be able to demonstrate increased knowledge of the clinical treatment of allergy/asthma/immunology and how new information can be applied to their own practices.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this activity, participants should be able to:

-

•

Recognize the salient virologic, epidemiologic, and clinical features of the three major zoonotic coronavirus epidemics this century.

-

•

Describe the clinical manifestations and outcomes of COVID-19, in particular in patients with asthma, allergy, and primary immunodeficiency.

Release Date: April 1, 2021

Expiration Date: March 31, 2023

Target Audience

Physicians involved in providing patient care in the field of allergy/asthma/immunology

Accreditation

The American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Designation

The American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit TM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Disclosure Policy

As required by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and in accordance with the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) policy, all CME planners, presenters, moderators, authors, reviewers, and other individuals in a position to control and/or influence the content of an activity must disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest that have occurred within the past 12 months. All identified conflicts of interest must be resolved, and the educational content thoroughly vetted for fair balance, scientific objectivity, and appropriateness of patient care recommendations. It is required that disclosure be provided to the learners prior to the start of the activity. Individuals with no relevant financial relationships must also inform the learners that no relevant financial relationships exist. Learners must also be informed when off-label, experimental/investigational uses of drugs or devices are discussed in an educational activity or included in related materials. Disclosure in no way implies that the information presented is biased or of lesser quality. It is incumbent upon course participants to be aware of these factors in interpreting the program contents and evaluating recommendations. Moreover, expressed views do not necessarily reflect the opinions of ACAAI.

Disclosure of Relevant Financial Relationships

All identified conflicts of interest have been resolved. Any unapproved/investigative uses of therapeutic agents/devices discussed are appropriately noted.

Planning Committee

-

•

Larry Borish, MD, Consultant, Consulting Fee: Avrio-Purdue; Advisory Board, Consulting Fee: Bristol Myers Squibb, Genzyme, Sanofi; Clinical Research, Contracted Research: Regeneron, Money to Institution; Investigator, Grant, Money to Institution: GlaxoSmithKline

-

•

Mariana C. Castells, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose

-

•

Anne K. Ellis, MD, MSc, FRCPC, Advisory Board, Honorarium: Alk Abello, AstraZeneca, Aralez, Bausch Health, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer; Speaker, Honorarium: Alk Abello, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Medexus, Mylan; Research, Grants: Alk Abello, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, LLC. Medexus, Novartis, Regeneron; Independent Consultant, Fees: Bayer LLC, Regeneron

-

•

Mitchell Grayson, MD, Advisory Board, Honorarium: DBV Technologies, Advisory Board, Consulting Fee: GlaxoSmithKline

-

•

Matthew Greenhawt, MD, Consultant, Fees: Aquestive; Advisory Board, Honorarium: Allergenis, Allergy Therapeutics, Aquestive, DBV Technologies, Intrommune, Novartis, Nutricia, Pfizer, Prota, Sanofi/Genzyme, US WorldMeds; Speaker, Honorarium: DBV Technologies

-

•

William D. Johnson, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclosure.

-

•

Donald Leung, MD, PhD, Advisory Board, Consulting Fee: Boehringer Ingelheim; Consultant, Honorarium: Genentech; Advisory Board, Honorarium: Leo Pharma; Speaker, Honorarium: Pfizer

-

•

Jay A. Lieberman, MD, Author, Research Investigator, Contracted Research, Money to Institution: Aimmune; Advisory Board/Research Investigator, Honorarium/Contracted Research, Money to Institution: DBV Technologies; Advisory Board, Honorarium: Genentech; Research Investigator, Contracted Research, Money to Institution: Regeneron

-

•

Gailen D. Marshall, Jr, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Anna Nowak-Wegrzyn, MD, PhD, Advisory Board, Honorarium: Nestle; Novartis, Regeneron; Speaker, Honorarium: Nutricia; Author, Royalty: UpToDate

-

•

John J. Oppenheimer, MD, Consultant, Consulting Fee: AstraZeneca; Research, Consulting Fee: GlaxoSmithKline; Adjudication/dsmb, Novartis/Abbvie/Regeneron/Sanofi

-

•

Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, PhD, Independent Contractor, Honorarium: Abbott; Consultant, Independent Contractor, Consulting Fee, Contracted Research: DBV Technologies; Advisory Board, Contracted Research, Honorarium. Contracted Research: Novartis; Consultant, Independent Contractor, Consulting Fee: Intellectual Property Rights, Regeneron; Independent Contractor, Contracted Research: Sanofi

Authors

-

•

Monica Fung, MD, MPH, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Iris Otani, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Michele Pham, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

-

•

Jennifer Babik, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Recognition of Commercial Support: This activity has not received external commercial support.

Copyright Statement: ©2015-2021 ACAAI. All rights reserved.

CME Inquiries: Contact the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology at education@acaai.org or 847-427-1200.

Introduction

There are 4 common coronaviruses that cause mild upper respiratory illness in humans. Over the past 20 years, there have been 3 major zoonotic coronavirus (CoV) epidemics with 3 other highly pathogenic CoV: (1) severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by SARS-CoV, (2) Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by MERS-CoV, and now (3) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS and MERS each caused fewer than a thousand deaths, but COVID-19 has spread worldwide and, at the time of this review, has infected nearly 50 million patients and caused more than a million deaths.1 In this article, we will describe each of these syndromes in detail, with a particular focus on patients with asthma, allergy, and primary immunodeficiency.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Virology and Immune Response

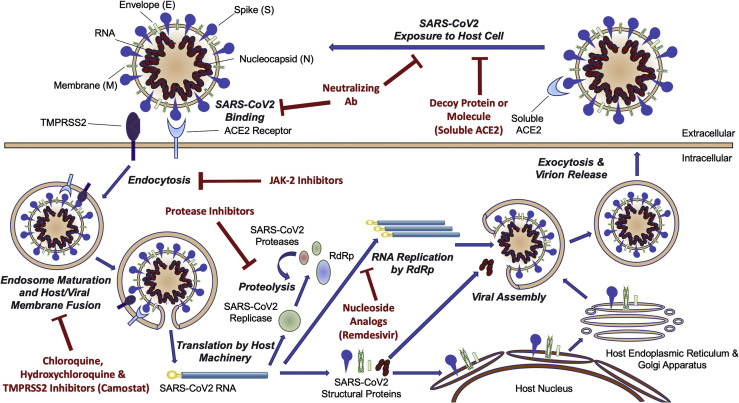

Like other CoV, SARS-CoV is a single-stranded RNA virus in the Betacoronavirus genera of the Coronaviridae family.2 Bats are the natural reservoir for SARS-CoV, and the palm civet (a cat-like Asian mammal) is a possible intermediate host.3, 4, 5 The viral life cycle is similar to that of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig 1 ). Severe disease seems to be mediated by the activation of TH1 cell response and the release of proinflammatory cytokines.6 SARS-CoV evades the human interferon (IFN) response by means of multiple active and passive strategies, such as inhibiting IFN regulatory factor 3, a transcription factor that activates IFN genes.7 , 8

Figure 1.

The lifecycle of SARS-CoV-2. ACE2 receptor binding, endocytosis, viral genome translation, and amplification, followed by virion assembly and exocytosis. ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2. (Reproduced with permission from Atri et al,48JACC Basic Transl Sci; 2020; 5(5):518-536.)

Epidemiology and Transmission

SARS initially emerged in the People's Republic of China during the fall of 2002, which then spread worldwide to 29 countries, creating large outbreaks in the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, Republic of China, Singapore, and Toronto, Canada.9 There were 19 probable and 8 confirmed cases in the United States.10 The epidemic ended in July 2003 with a total of 8098 cases and 774 deaths (case fatality rate of 9.6%).9 Since then, there have only been a few sporadic cases of SARS reported, mostly associated with laboratory breaches.6 The main mode of transmission for SARS-CoV is by means of respiratory droplets and possibly fomites.11 Nosocomial transmission was well documented.6

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period for SARS is approximately 5 days (range 2-14 days).2 The most common presenting symptoms are fever (99%-100%), chills (15%-73%), cough (62%-100%), shortness of breath (40%-42%), headache (20%-56%), and myalgia (31%-61%).2 Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea) occur in less than a third of patients.2 Asymptomatic infection is uncommon.6

Diagnosis

SARS-CoV was detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on respiratory, blood, and stool specimens, often using a combination of specimens given the imperfect sensitivity (80% at best) of a single nasopharyngeal sample.6 Serologic testing was used for epidemiologic surveillance.6

Treatment and Vaccines

Supportive care was the mainstay of management for SARS. Multiple drugs were tried for treatment, but few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were done. Ribavirin did not have clinical efficacy and led to hemolysis in many patients.6 Retrospective studies revealed possible benefits from lopinavir/ritonavir, IFN, and convalescent plasma.2 , 6 , 12 Steroids seemed to be harmful, leading to increased mortality and prolonged viremia.2 , 6 There were early vaccine trials in macaques and mice, but no completed human trials.6

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

Virology and Immune Response

MERS-CoV is another Betacoronavirus in the same genus SARS-CoV that infects humans and camels.13 , 14 Although bats serve as a MERS-CoV reservoir,15 , 16 the immediate host is the dromedary camel that then infects humans.17

Although the lifecycle of MERS-CoV is largely similar to that of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV differs in host binding receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (also known as CD26), which is found on epithelial and endothelial cells of the human lung, kidney, small intestine, liver, and prostate.18, 19, 20 The host immune response to MERS-CoV is characterized by elevated proinflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin [IL]-6 and CXCL-10)21 followed by TH1 and type 1 cytotoxic T-cell responses during convalescence.

Epidemiology and Transmission

The first MERS case was reported in September 2012 in Saudi Arabia,22 and there have been more than 2400 cases and 800 deaths reported to the World Health Organization (WHO).23 Cases have occurred predominantly in persons residing in or traveling from the Arabian Peninsula. The median age was 52 years (interquartile range, 37-65 years), and 79% were men.24

Transmission primary occurs by means of close contact between dromedary camels and humans.15 , 17 , 25 Although human-to-human transmission has been confirmed,24 , 26, 27, 28 humans are considered transient or terminal hosts with no sustained human-to-human transmission.29 Reported R0 estimates vary significantly (0.45-8.1),30 with increased spreading described in nosocomial outbreaks.31 Primary modes of transmission are droplet and contact, with potential for aerosol spread in close unprotected contact.32

Clinical Manifestations

The average incubation period for MERS is 5 to 7 days.33 , 34 The most common clinical presentation is severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome in an adult. Among 47 patients with MERS-CoV infection in Saudi Arabia, fever (98%) and cough (83%) were present in most; less common symptoms included myalgia, diarrhea, and sore throat. All patients had abnormal chest imaging, but there were no clear characteristic laboratory findings. Approximately 89% of patients required intensive care and 72% required mechanical ventilation, with a case fatality rate of 60%.27

Diagnosis

Real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) testing is the main diagnostic for MERS-CoV. Given the severity of disease and risk for human-to-human transmission, a combined approach to testing is favored with PCR testing of the lower respiratory tract, upper respiratory tract, and serum (in order of preference).15 , 26 , 35

Treatment and Vaccines

There are no therapeutic agents with proven clinical efficacy for MERS-CoV, and supportive care is the mainstay of therapy. Retrospective studies of antiviral agents (ribavirin or IFN) and steroids among critically ill patients with MERS have exhibited either statistically nonsignficant trends toward benefit or suggested increased mortality.36, 37, 38 Although convalescent plasma,39 monoclonal antibodies,40 , 41 and novel antivirals (fusion inhibitor42; nucleotide analog43) exhibited promise in animal studies, these therapies were not studied in humans.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Virology and Immune Response

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel Betacoronavirus that is related to but distinct from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.44 SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to bat and pangolin coronaviruses44 , 45; it has been theorized that bats are the natural reservoir of the virus and the pangolin, an endangered and frequently trafficked mammal, may have served as an intermediate host.45 Although a market in Wuhan, People's Republic of China, was initially thought to be the source of the outbreak, this has not been definitely proven.45

The lifecycle of SARS-CoV-2 is believed to be similar to that of SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses (Fig 1). The spike protein on the virion surface binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor on host cells.46 The virus is then internalized by means of endocytosis, which is mediated by spike protein cleavage by the serine protease transmembrane serine protease 2.47 The viral genome is then translated into a polyprotein that is cleaved by both host and viral proteases; a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase then amplifies the genome, and virions are assembled and released.48 It is notable that the ACE2 receptor has broad tissue distribution, including the lungs, upper airway, myocardium, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and vascular endothelial cells in most tissues.49 , 50 This likely, in part, explains the broad clinical manifestations of COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 induces a limited type I and type III IFN response but high chemokine and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. This exuberant inflammatory response is thought to play a role in more severe disease given the association between elevated inflammatory markers and mortality.51

Epidemiology and Transmission

Since the first reports of COVID-19 cases in Wuhan, the People's Republic of China, in late 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has spread worldwide, infecting nearly 30 million patients and causing close to 1 million deaths.1 , 52

Older patients and those with comorbidities are at increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease.53, 54, 55 Data from multiple countries have exhibited incrementally higher rates of hospitalization and mortality with increasing age.56, 57, 58 In the People's Republic of China, patients with COVID-19 who were in the age range of 70 to 79 years and 80 years or older experienced case fatality rates of 8% and 15%, respectively, compared with the overall case fatality rate of 2.3%.59 Other established epidemiologic risk factors for severe COVID-19 include diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and obesity.56, 57, 58 , 60 In a large prospective cohort from the United Kingdom, significantly increased mortality was seen among COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio [HR], 1.16), liver disease (HR, 1.51), obesity (HR, 1.33), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.33).60 Immunosuppressed patients with malignancy and solid organ transplant recipients seem to be at increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease and death, whereas for those with other types of immunocompromise, current evidence is less clear.61 Within the United States, there are significant racial disparities in COVID-19 disease and death likely as a result of social conditions and systemic health inequities among racial groups.62

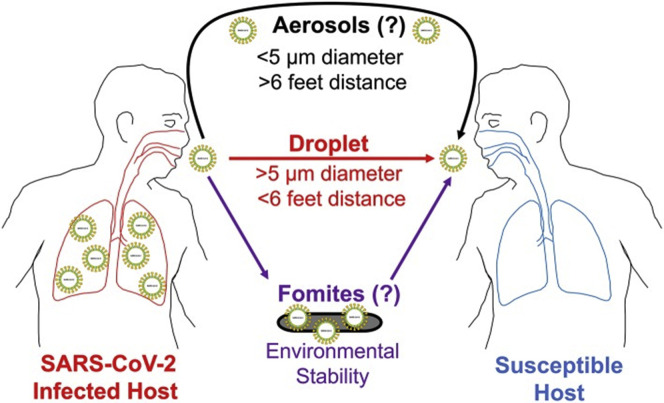

The current understanding of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is incomplete. Person-to-person transmission by means of close-range respiratory droplets is considered the predominant mode of transmission (Fig 2 ).63 , 64 Although SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted as an airborne aerosol,65, 66, 67 this has not been clearly exhibited in the real world, including among health care workers.68 Although SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in nonrespiratory specimens (stool, blood, semen, ocular fluid), the likelihood of bloodborne or nonmucous membrane transmission seems to be low.69, 70, 71

Figure 2.

Modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The duration and degree of infectivity of an individual with COVID-19 depend on multiple factors. Asymptomatic or presymptomatic transmission plays a large role, with several studies documenting transmission up to 6 days before symptom onset,72 , 73 A persistent positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 does not necessarily indicate the presence of a live infective virus,63 but viral load as assessed by PCR cycle threshold may.74 Risk of infection is also related to the type and duration of exposure, with prolonged close contact in closed or crowded settings conveying the highest risk.75

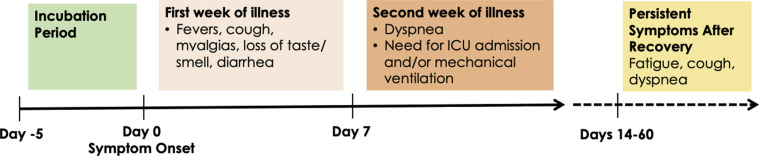

Clinical Manifestations

Approximately 40% to 45% of SARS-CoV-2 infections are asymptomatic.76 For the remaining patients with symptomatic infection, approximately 80% are mild (not requiring hospitalization), 15% are moderate to severe (requiring hospitalization), and 5% are critical (requiring intensive care unit [ICU] care).59 , 77, 78, 79 COVID-19 can involve almost every system in the body. The median incubation period between infection and symptom onset is 5 days. Patients often do not manifest signs and symptoms of a severe disease until the second week of illness (Fig 3 ).55 , 80 Of note, 2 recent reports describe that a significant proportion of patients have persistent symptoms weeks to months after recovery from acute infection, even in young patients with no comorbidities.81 , 82

Figure 3.

The clinical course of COVID-19. Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit.

Systemic and Respiratory Manifestations

The main systemic manifestations of COVID-19 are fever (>75%), myalgias (10%-50%), and fatigue (20%-40%).53 , 55 , 79 , 83, 84, 85 Cough is seen in 45% to 80% of patients (usually dry) and dyspnea in 20% to 55%. Headache and symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection (sore throat and rhinorrhea) are seen in less than 20% of patients.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Diarrhea or nausea/vomiting is seen in only 5% to 9% of patients.86, 87, 88 More importantly, gastrointestinal symptoms can rarely be the only presenting symptoms (ie, without respiratory complaints) of COVID-19.89, 90, 91

Cardiac Manifestations

Arrhythmias have been described in 7% to 17% of hospitalized patients83 , 92 and cardiac injury (defined by elevation in troponin level) in 7% to 28%.93 Multiple studies have found that there is no association between the use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition or the risk for more severe disease.94, 95, 96, 97

Head and Neck Manifestations

Disorders of taste (dysgeusia, ageusia) and smell (hyposmia, anosmia) are quite common in COVID-19, ranging anywhere from 34% to 89% of patients.98, 99, 100 These symptoms can manifest before other respiratory symptoms and can be present without nasal congestion, raising the possibility that disorders of taste and smell may at least be in part a direct effect of the virus rather than solely because of nasal inflammation and obstruction.99 Ocular symptoms have been described in 1% to 32% of patients, with conjunctivitis being most common.101, 102, 103, 104, 105

Neurologic Manifestations

Neurologic findings have been described in 36% to 57% of hospitalized patients.106, 107, 108 The most common symptoms were dizziness, headache, and impaired consciousness; stroke was seen in only 2% to 3% of patients. It is unclear whether neurologic effects are related to a direct effect of the virus, hypercoagulability or inflammation caused by the virus, or are simply the result of severe medical illness in patients with preexisting vascular risk factors.106 , 109 Several reports have also described Guillain-Barré syndrome in patients with COVID-19.110, 111, 112

Hematologic Manifestations

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism) in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 ranges from approximately 15% to 50%, and the risk seems to be higher in patients with elevated D-dimer levels.113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119 The role of therapeutic anticoagulation in severe COVID-19 is controversial120—the risks and benefits remain unclear and prospective trials are needed.

Renal Manifestations

Acute kidney injury is seen in 3% to 11% of hospitalized patients, requiring renal replacement therapy in 2% to 7%.121 , 122 It is not clear whether kidney injury is because of direct viral effects (there are high levels of ACE2 expression in the kidney) or whether this is a byproduct of inflammation or hemodynamic shifts.121 , 122

Dermatologic Manifestations

Rash has been reported from less than 1% to 20% of patients, depending on the study.53 , 123, 124, 125 The most common morphologies reported are erythematous, urticarial, and vesicular rashes. Chilblain-like lesions (known colloquially as "COVID toes") have been described typically in patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.126 , 127 However, more recent data argue against a causal link; rather, these lesions may be owing to lifestyle changes (eg, spending more time barefoot) during shelter in place.128 , 129

Inflammatory Syndromes

The increased levels of inflammatory markers in patients with severe COVID-19 (discussed in the subsequent sections) have raised the possibility that some manifestations of critical illness in COVID-19 may be caused by a cytokine storm. However, recent data suggest that the levels of inflammatory cytokines are similar in critically ill patients with and without COVID-19.130 , 131 Nevertheless, the inflammatory response in COVID-19 underlies the rationale for trying to treat COVID-19 with anti-inflammatory medications (eg, immunosuppressives and steroids). Another multisystem inflammatory syndrome has recently been described in children, which has similarities to Kawasaki disease but is thought to be a distinct entity.132 , 133

Laboratory Findings

Multiple studies have tried to identify factors that could predict disease severity, disease progression, and/or death. Factors that have been identified to date include older age, presence of comorbidities, low oxygen saturation, levels of inflammatory markers (eg, lactic acid dehydrogenase), and chest computed tomography (CT) severity.134, 135, 136, 137 However, when and how to use these data from a clinical or triage standpoint is not yet clear.

Imaging

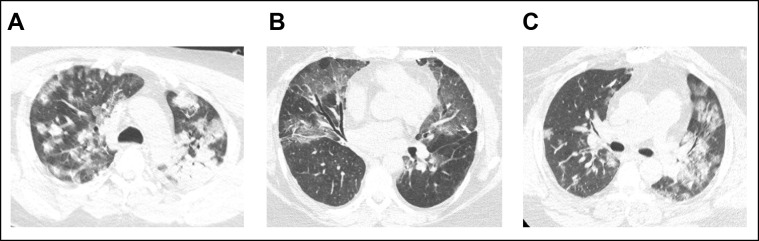

Chest radiographic findings are abnormal in 60% and chest CT scans in 86% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.53 The most common chest CT findings are ground-glass opacities (83%-87%) that are usually bilateral (78%-80%) and in a peripheral distribution (75%-77%).138 , 139 Consolidations, septal thickening, and crazy paving are also common. Typical CT findings are illustrated in Figure 4 .

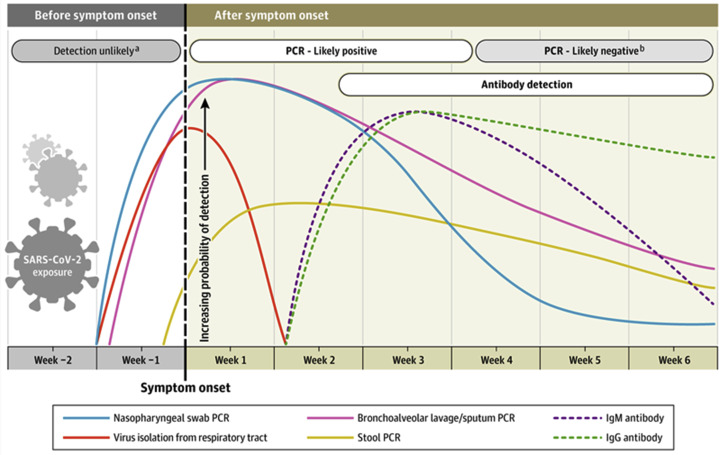

Figure 5.

Time course of viral exposure, clinical infection, and the results of clinical assays for SARS-CoV-2 and the immune response to it. From N Sethuraman et al., JAMA 2020;323:2249.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography findings from three patients with COVID-19 (A–C). Bilateral ground-glass opacities can be seen, often with a peripheral distribution.

Clinical Manifestations Among Patients with Allergy and Atopy

Although data are limited, initial studies suggest that asthma and allergies do not particularly predispose patients to coronavirus infections. Asthma exacerbations did not seem to increase during the previous SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV outbreaks.140 , 141 During the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, asthma has been reported in 0% to 23.9% of patients with COVID-19 (Table 1 ). Studies have found asthma prevalence in patients with COVID-19 to be lower than the asthma prevalence reported in respective regions.142 , 143 Similarly, rates of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis were all lower in patients with COVID-19 (9.9%, 57.4%, and 1.9%, respectively) compared with the total tested population (14.9%, 63.1%, 3.9%, respectively) in a nationwide Korean cohort study.144 When 37 major pediatric asthma and allergy centers estimated to treat 1000 patients with asthma in Europe and Turkey were surveyed between September 2019 and July 2020, none reported any symptomatic COVID-19 cases or positive SARS-CoV-2 tests among their patients.145

Table 1.

Percentage and Number of Patients With Asthma Among Patients With COVID-19 and Reports of Clinical COVID-19 Outcomes Associated With Asthma

| Author, year | N | Age, yb | Hospitalized | With asthma, % (n) | Study location | Asthma associated with | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | |||||||

| Zhang et al,223 2020 | 140 | 57 (25-87) | median (range) | 140 | 0.0 (0) | Wuhan, People's Republic of China | |

| Zhang et al,224 2020 | 290 | 57 (22-88) | median (range) | 290 | 0.3 (1) | Wuhan, People's Republic of China | |

| Li et al,225 2020 | 548 | 60 (48-69) | median (IQR) | 548 | 0.9 (5) | Wuhan, People's Republic of China | |

| Song et al,159 2020 | 961 | — | — | 961 | 2.3 (22) | Wuhan, People's Republic of China | |

| Guan et al,173 2020 | 1590 | 49 | median | — | 0.0 (0) | People's Republic of China | |

| Lee et al,226 2020 | 303 | 25 (22-36) | median (IQR) | 1 | 0.3 (1) | Cheonan, South Korea | |

| Yang et al,144 2020 | 7340 | ≥20 | — | — | 9.9 (725) | South Korea | Increased risk for intubation, ICU admission, death |

| Garcia-Pachon et al,227 2020 | 376 | 54 (42-69) | median (IQR) | 158 | 2.7 (10) | Alicante, Spain | |

| San-Juan et al,228 2020a | 32 | 32 ± 7 | mean ± SD | 29 | 12.5 (4) | Madrid, Spain | |

| Beurnier et al,149 2020 | 768 | 54 (42-67) | median (IQR) | 768 | 4.8 (37) | Paris, France | Lower but not significantly different mortality rate |

| Grandbastien et al,229 2020 | 106 | 64 (54-72) | median (IQR) | 106 | 21.7 (23) | Strasbourg, France | No difference in length of admission, oxygen supplementation needs, need for intubation or ICU level of care |

| Avdeev et al,230 2020 | 1307 | 62 (34-83) | median (range) | 1307 | 1.8 (23) | Moscow, Russia | |

| Almazeedi et al,231 2020 | 1096 | 41 | median | 1096 | 3.9 (43) | State of Kuwait | |

| Ferguson et al,232 2020 | 72 | 60 (43-71) | median (IQR) | 72 | 9.7 (7) | California | |

| Duanmu et al,233 2020 | 100 | 45 (32-65) | median (IQR) | 24 | 10.0 (10) | California | |

| Gold et al,234 2020 | 305 | 60 | median | — | 10.5 (32) | Georgia | |

| Chhiba et al,166 2020 | 1526 | — | — | 853 | 14.4 (220) | Illinois | No difference in risk for hospitalization |

| Mahdavinia et al,150 2020 | 935 | — | — | — | 25.8 (241) | Illinois | Longer intubation time No difference in mortality rate |

| Corsini Campioli et al,235 2020 | 251 | 53 | median | 62 | 18.3 (46) | Minnesota | Lower likelihood of achieving cessation of viral RNA shedding 3 weeks after symptom onset |

| Lovinsky-Desir et al,146 2020 | 1298 | ≤65 | — | 1298 | 12.6 (163) | New York | No difference in length of admission, need for intubation, length of intubation, need for tracheostomy, hospital readmission, mortality |

| Singer et al,236 2020 | 1651 | 50 | median | — | 6.0 (99) | New York | |

| Richardson et al,84 2020 | 5700 | 63 | median | — | 9.0 (513) | New York | |

| Lieberman-Cribbin et al,151 2020 | 6250 | 57 | median | — | 4.4 (272) | New York | No difference in mortality rate |

| Andrikopoulou et al,155 2020a | 158 | — | — | 87 | 11.4 (18) | New York | |

| Salacup et al,237 2020 | 242 | 66 (58-76) | median (IQR) | 242 | 7.4 (18) | Pennsylvania | |

| Bhatraju et al,238 2020 | 24 | 64 (23-97) | mean (range) | 24 | 14.0 (3) | Washington | |

| Pediatric | |||||||

| Du et al,239 2020 | 182 | 6 (0-15) | median (range) | 182 | 0.5 (1) | Wuhan, People's Republic of China | |

| Ibrahim et al,147 2020 | 4 | 13 ± 5 | mean ± SD | 0 | 25 (1) | Melbourne, Australia | |

| Chao et al,240 2020 | 67 | ≤21 | — | 46 | 23.9 (11)c | New York | No difference in need for PICU level of care |

| Otto et al,241 2020 | 424 | 10 (1-15) | median (IQR) | 77 | 20.5 (87) | Pennsylvania | |

| DeBiasi et al,242 2020 | 177 | 10 (0-34) | median (range) | 44 | 19.8 (35) | Washington, District of Columbia | |

Abbreviations: B, benralizumab; COVID-19, coronavirus 2019; D, dupilumab; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; M, mepolizumab; O, omalizumab; PICU, pediatric ICU; R, reslizumab.

Studies that reported specifically on pregnant women only.

Ages were rounded to the nearest whole number in years.

This study reported the number of asthma patients only among hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Of note, 3 studies suggest that perhaps asthma rates may be concentrated in pediatric patients with COVID-19. However, data are limited, studies were done in different countries, and definitive conclusions cannot be reached. A higher asthma prevalence was observed among pediatric patients aged 21 years and below (32.6%, 13/55) than in the whole cohort of patients with COVID-19 aged 65 years and below in New York (12.6%, 163/1298).146 In pediatric patients from Australia, asthma prevalence was higher among patients with COVID-19 (25% [1/4]) than in the whole cohort (10.9%, 47/433),147 whereas, in adult patients from South Korea, asthma prevalence was lower among patients with COVID-19 (9.9%, 725/7340) than in the whole cohort (14.9%, 32,845/219,959]).144

Data regarding the effect of asthma on COVID-19 outcomes illustrated in Table 1 are mixed and conflicting. Severe asthma was associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related death in 1 study reviewing a health analytics platform with records of 40% of patients from the United Kingdom,148 but asthma was not necessarily associated with increased mortality in other studies.146 , 149, 150, 151 Interestingly, in at least 2 studies in which asthma was associated with worse clinical outcomes, nonallergic asthma accounted for the increased risk for worse outcomes (severe COVID-19, ICU admission, intubation, and death).144 , 152

The effect of asthma on COVID-19 outcomes may differ on the basis of other patient characteristics, although, again, data are limited. One study found male sex, Asian race, and comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to be risk factors for hospitalization among patients with asthma.153 Another study from UK Biobank found that asthma was a risk factor for COVID-19 hospitalization among women but not men.154 Among pregnant women, those with moderate to severe COVID-19 were more likely to have asthma than those with mild COVID-19.155

It has been hypothesized that reduced ACE2 expression could be protective against COVID-19 infection,156 although data remain limited and conflicting. Asthma, allergic rhinitis, and increasing severity of allergic sensitization have been associated with reductions in ACE2 expression in airway epithelial cells.157 , 158 Asthma has been associated with lower ACE2 expression and a lower risk of developing severe COVID-19 compared with COPD.159 IL-13, a cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple atopic conditions, including asthma,160 were found to reduce ACE2 and increase transmembrane serine protease 2 expression in airway epithelial cells.157

Conversely, asthma has also been associated with increased ACE2 expression in bronchial biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and blood.161 In addition, a study comparing 330 patients with asthma and 79 healthy control patients and a study comparing 77 patients with asthma and 17 healthy control patients found that ACE2 expression was similar between patients with asthma and nonpatients with asthma.162 , 163 Notably, there was higher ACE2 expression among patients with asthma who were men, African American, or had diabetes mellitus, and the authors have suggested that a higher level of monitoring may be needed for these patients.162 Indeed, African American race and diabetes mellitus were implicated as risk factors for hospitalization in patients with asthma with COVID-19153 and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was observed with a significantly higher prevalence in patients with asthma with COVID-19.164

There has also been speculation as to whether inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) could be protective against or provide treatment benefit for COVID-19 infection. Currently, there is no literature clearly indicating whether ICS use is beneficial or detrimental to COVID-19 outcomes.165 In one study of 1562 patients, ICS use did not seem to affect the risk for hospitalization among patients with asthma in Chicago.166 There has been a case series of inhaled ciclesonide initiation temporally correlating to improvement in 3 hospitalized patients with COVID-19.167 In vitro, a combination of glycopyrronium, formoterol, and budesonide seemed to inhibit viral replication in infected nasal and tracheal epithelial cells168 and ACE2 expression was found to be decreased in sputum cells of patients with asthma and COPD on ICS.162 , 169

Questions have also been raised regarding the effect of type 2 biologic therapy on COVID-19 infectivity and outcomes. Observational experiences reported to date do not provide evidence that type 2 biologics are associated with increased risk for COVID-19 infection or higher COVID-19 disease severity. To date, reports specifically investigating COVID-19 infectivity and outcomes in patients on type 2 biologic therapy found that among 1938 patients on anti–immunoglobulin E (IgE) (n = 610), anti–IL-5 or anti–IL5R (n = 844), or anti–IL-14/IL-13 (n = 483), COVID-19 infection was observed in 55 (2.8%), with 6 severe cases and 1 mortality. In addition, a recent case report specifically described milder than expected COVID-19 severity in a patient on dupilumab (Table 2 ).170

Table 2.

Reports of How Many Patients on Type 2 Biologics Developed COVID-19, the Outcomes of COVID-19 Infections, and whether Biologics Were Held or Continued During Infection

| Author, year | O | B | M | R | D | Indication | Patients with COVID-19 | Outcome | Biologic management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lommatzsch et al,243 2020 | 1 | — | — | — | — | Asthma | 1 | Home | Continued (home self-administration) |

| Garcia-Pachon et al,227 2020 | 1 | — | — | — | — | Asthma | 1 | Asymptomatic | NR |

| Beurnier et al,149 2020 | 2 | — | — | — | — | Asthma | 2 | Hospitalized (n = 1) ICU (n = 1) |

Continued (inpatient) |

| Matucci et al,244 2020 | 145 | 124 | 200 | — | 4 | Asthma | 4 | Home, on B (n = 1) Home, on O (n = 1) ICU, on O (n = 2) |

Held during active infection (n = 3) |

| Renner et al,245 2020 | — | 1 | — | — | — | Asthma | 1 | Home | NR |

| García-Moguel et al,246 2020 | — | 2 | — | — | — | Asthma | 2 | Home (n = 1) Hospitalized (n = 1) |

NR |

| Förster-Ruhrmann et al,170 2020 | — | — | — | — | 1 | CRSwNP | 1 | Home | Continued |

| Bhalla et al,247 2020 | — | — | — | — | 1 | Asthma | 1 | Mild | Already discontinued 3 months before getting COVID-19 |

| Carugno et al,248 2020 | — | — | — | — | 30 | AD | 0 | NA | NA |

| Caroppo et al,249 2020 | — | — | — | — | 1 | AD | 1 | Home | NR |

| Ordóñez-Rubiano et al,250 2020 | — | — | — | — | 1 | AD | 1 | Asymptomatic | Continued |

| Criado et al,251 2020 | 1 | — | — | — | — | urticaria | 1 | Home | Started with improvement of urticaria |

| Ferrucci et al,252 2020a | — | — | — | — | 245 | AD | 2 | Mild (n = 1) Hospitalized (n = 1) |

Continued |

| Napolitano et al,253 2020 | — | — | — | — | 200 | AD | 0 | NA | NA |

| Heffler et al,164 2020 | 708b | 796b | — | Asthma | 22c | Recovered, on O (n = 6) Recovered, on M (n = 13) Death, on M (n = 1) Recovered, on B (n = 2) |

NR | ||

| Zhu et al,152 2020d | — | — | — | — | — | Asthma | 16 | Home (n = 11) Hospitalized (n = 2) ICU (n = 3) |

NR |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; B, benralizumab; COVID-19, coronavirus 2019; CRSwNP, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; D, dupilumab; ICU, intensive care unit; IL, interleukin; M, mepolizumab; NA, not reported; NR, not applicable; O, omalizumab; R, reslizumab.

In this study, co-infected family members of both patients with COVID-19 died from COVID-19.

Numbers were calculated from percentages reported (47.1% of 1504 patients were treated with anti–immunoglobulin E and 52.9% of 1504 patients were treated with anti–IL-5 or anti–IL-5R).

Authors included both confirmed and suspected COVID-19 cases in their report.

Specific biologics prescribed were not reported.

In a study specifically investigating risk factors for hospitalization, ICU stay, and mortality among patients with asthma and COVID-19, both ICS and biologic use did not differ between patients with COVID-19 having asthma who needed general vs ICU level of care. Short-acting β agonist–only use was associated with a lower risk for hospitalization.153

Multiple position statements (Global Initiative for Asthma, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, British Thoracic Society, and European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology) have been released recommending continued treatments that are effective for patients with atopy, including type 2 biologics, given the current lack of evidence that type 2 biologics increase infectivity or mortality and the risk of losing disease control if type 2 biologics were to be stopped.171 , 172

Clinical Manifestations Among Patients with Primary Immunodeficiency

Not all primary immunodeficiencies (PID) are thought to be equally susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infections and its complications, but this is largely based on knowledge of the immune system function in pathogen response given the limited published reports (Table 3 ). COVID-19 data from the People's Republic of China describe very few patients with immunodeficiencies. Of note, 2 studies of more than a thousand patients with COVID-19 each reported that 0.19% of their study population had an immunodeficiency and milder disease courses, but the specifics of their diagnoses were not elaborated on.53 , 173 Given the lack of robust information regarding COVID-19 in patients with PID, likely owing to the small numbers of such patients, reports from databases and group studies will particularly helpful to further understanding. The largest report of patients with PID infected with SARS-CoV-2 comes from an international effort among immunologists who described 94 patients with a wide range of PID diagnoses.174 A total of 59 patients (63%) required hospitalization, and 16% of all patients required intensive care. All adult patients who died from SARS-CoV-2 had preexisting comorbidities.174

Table 3.

Published Reports of Patients With Specific Primary Immunodeficiencies Who Developed SARS-CoV-2 Infections

| Author, year | Patient diagnoses (N) | Geographic location | Study design | Number with COVID-19 | Symptoms | Clinical severity (%) | COVID-19 treatment (%) | Outcomes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyts et al,174 2020 | PID/IEIa,b | International Argentina, Chile, Brazil, France, Italy, Mexico, Spain, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, United States |

Retrospective study | Total 94 | Asymptomatic, fever, dyspnea, cough, upper respiratory symptoms, GI symptoms, myalgias | Home (36), Asymptomatic (11), Hospitalized (63), ICU (19) | Antibiotics (51), IVIG (11), hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine (33), corticosteroids (21), mAbs (tocilizumab, anakinra) (9), antivirals (lopinavir and ritonavir) (13), remdesivir (10), favipravir (1), anticoagulants (13), convalescent plasma (5) | Recovered (90) Died (10) |

| Antibody deficiency | 53 | Home (N = 19), Hospitalized (N = 34), ICU (N = 10) | Recovered (87) Died (13) |

|||||

| CID | 14 | Home (N = 6), Hospitalized (N = 8), ICU (N = 3) | Recovered (90) | |||||

| Immune dysregulation | 9 | Home (N = 1), Hospitalized (N = 9) | Recovered (89) Died (11) |

|||||

| Autoinflammation | 7 | Home (N = 5), hospitalized (N = 2), ICU (N = 1) | Recovered (100) | |||||

| Phagocyte defects | 6 | Home (N = 3), Hospitalized (N = 3), ICU (N = 1) | Recovered (83) Died (17) |

|||||

| Innate immunity defect | 3 | Home (N = 1), Hospitalized (N = 2) | Recovered (100) | |||||

| Bone marrow failure | 2 | Hospitalized (N = 2) | Recovered (100) | |||||

| Quinti et al,182 2020 | XLA (1), ARA (1), CVID (5) | Italy | Case series | 7 | Asymptomatic, fever, dyspnea, cough | Home (14), Hospitalized (86), ICU (43) | Antibiotics (71), Antivirals (100), hydroxychloroquine (100), IVIG (100), tocilizumab (43) | Recovered (86), died (14—1 CVID patient) |

| Soresina et al,187 2020 | XLA (2)c | Italy | Case series | 2 | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Hospitalized (100) | Antibiotics (100), hydroxychloroquine (100), IVIG 100), lopinavir/ritonavir (50) | Recovered (100) |

| Jin et al,186 2020 | XLA (3)c | United States (NY) | Case series | 3 | Fever, dyspnea, cough | Hospitalized (100) | Antibiotics (100), anticoagulants (67), convalescent plasma (100), IVIG (100), remdesivir (33) | Recovered |

| Fil et al,181 2020 and Aljaberi et al,188 2020c | CVID (1) | United States (OH) | Case report | 1 | Fever, dyspnea, cough, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea | ICU | Antibiotics, home hydroxychloroquine increased from 200 mg twice daily to thrice daily, IVIG | Recovered |

| Mullur et al,183 2020 | CVID (1) | United States (MA) | Case report | 1 | Fever, dyspnea, cough | ICU | Antibiotics, Convalescent plasma, IVIG, remdesivir | Died |

| Ho et al,176 2020 | CVID (9), hypogammaglobulinemia (1), IgA-IgG2 deficiency (1), XLA (3), XHIGM (1), interferon gamma receptor 2 deficiencyc,d | United States (NY) | Case series | 16 | Fever, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, emesis, stomatitis | Home (25), Hospitalized (75), ICU (31) | Antibiotics, hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids, investigational agent, convalescent plasma | Recovered (75) Died (25) |

| Abraham et al,254 2020 | NFKB2 loss of function (1)c | United States (OH) | Case report | 1 | Fever, cough, dyspnea, UR symptoms, anosmia | ICU | Remdesivir, tocilizumab, IVIG, convalescent plasma | Recovered |

| Dinkelbach et al,184 2020 | FNIP1 deficiency (1) | Germany | Case report | 1 | Fever, dyspnea, cough | ICU | Antibiotics, prednisolone, remdesivir | Recovered |

| van der Made et al,177 2020 | TLR7 deficiency (4) | Netherlands | Case series | 4 | Fever, dyspnea, cough, vomiting | ICU (100) | Antibiotics (100), chloroquine (50), corticosteroids (25), anticoagulation (25) | Recovered (75) Died (25) |

Abbreviations: ARA, autosomal recessive agammaglobulinemia; CID, combined immunodeficiency; CVID, common variable immune deficiency; FNIP1, folliculin interacting protein 1; GI, gastrointestinal; ICU, intensive care unit; IEI, idiopathic environmental intolerance; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; NFKB2, nuclear factor kappa B subunit 2; PID, primary immunodeficiencies; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; XLA, X-linked agammaglobulinemia.

Includes some previously reported cases.

Includes pediatric cases.

One patient in this report by Soresina et al.187 was also included in the case series by Quinti et al.182

Includes the same XLA cases as in Jin et al.186

The innate immune system is the first line of defense against pathogens, CoV is recognized by pattern recognition receptors—such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), particularly TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7, and retinoic acid–inducible gene 1 (RIG-1)–like receptors—that induce proinflammatory cytokines that help propagate antiviral responses.175 There have been few specific reports of COVID-19 in patients with known innate system immune deficiencies. From the larger international study, innate system immune deficiencies were described in 3 young children younger than 2 years of age that ranged from an asymptomatic child with STAT1 gain-of-function to a one-year-old man with interferon gamma receptor 2 deficiency who required ICU admission.174 , 176 In New York, the one-year-old boy with interferon gamma receptor 2 deficiency with COVID-19 and a miliary Mycobacterium avium coinfection was treated with steroids in the ICU but recovered.174 , 176 There was also a report of a young child in Italy who became infected with SARS-CoV-2 and developed mild myocarditis and recovered.174 A case series of 2 pairs of brothers in the Netherlands highlights a potential clinical presentation.177 All 4 patients were healthy and young, with a mean age of 26 years, who developed severe COVID-19 leading to mechanical ventilation.177 One patient died. Whole-exome sequencing performed found X-chromosomal loss-of-function mutations in TLR7, and on stimulation with a TLR7 agonist, type I IFN signaling was transcriptionally down-regulated, as was the production of type II IFNs.177 Significance of these findings is unclear, because patients with TLR7 deficiency have not been reported to have recurrent infections, and TLR signaling has been reported to be complex with redundancies.

T cell responses are thought to be particularly important as defenses against viral infections such as SARS-CoV-2. Many studies suggest that lymphopenia is associated with more severe COVID-19 disease.53 , 178, 179, 180 In 1 retrospective study of 1018 patients with COVID-19, all T lymphocyte subsets, especially CD8-positive T cells, were markedly lower in nonsurvivors than in survivors.178 Patients in the group with elevated IL-6 levels (>20 pg/mL) and lower CD8-positive T cell counts (<165 cells/μL) were older, had more comorbidities, increased need for mechanical ventilation, and ICU admission, and increased incidence of death.178 Though there are no published reports of COVID-19 in patients with PID having isolated primary T cell defects, there have been reports of some patients with combined immunodeficiencies; however, limited numbers do not allow, thus, validated conclusions regarding risk of infection or severity of COVID-19 disease cannot be drawn.174 These patients labeled as combined immunodeficiencies in the international study all required admission, with half needing ICU care.174

Predominantly antibody deficiencies represent the most common group of primary immunodeficiency diagnoses, and reports have found a wide range of clinical presentations of COVID-19 in these patients but suggest that the adaptive immune system may not be as critical in the defense against SARS-CoV-2 as other aspects of the immune system.174 , 176 , 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186

Cases of COVID-19 in children with PID are limited. From an international study of patients with PID, 32 of the 94 patients reported were younger than 18 years of age. Of those patients, 9 (28%) required ICU admission, and 2 (6%) died.174 The diagnoses of these children included STAT1 gain-of-function, GATA2 deficiency, phagocyte defects (eg, chronic granulomatous disease), combined immunodeficiency, common variable immune deficiency (CVID), hypogammaglobinemia, autoinflammatory syndromes (eg, Mediterranean fever), and immune dysregulation.174 One case report describes a moderately severe case of COVID-19 in a 7-year-old child with a rare folliculin interacting protein 1 deficiency that leads to cardiomyopathy, chronic lung disease, and a B-cell deficiency with hypogammaglobulinemia necessitating immunoglobulin replacement.184 This patient required a high-flow nasal cannula and developed cardiac dysfunction and renal failure but ultimately clinically improved.184 In a study of the Mexican open registry of patients with COVID-19, immunodeficiencies (3.8%) and asthma (3.8%) were the most frequently found preexisting conditions in the 21,161 patients younger than 18 years of age.185 The patients labeled with an immunodeficiency included “transient hypogammaglobulinemia, IgG subclass deficiency, impaired polysaccharide responsiveness, and IgA deficiency.”185 This study concluded that children with immunodeficiencies were associated with mild and moderate forms of COVID-19 disease.185 These findings may be influenced by biased reporting, given that patients with PID and asthma may have better access to medical care than others.

In the few reports describing COVID-19 in adult patients with CVID, X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), and autosomal-recessive agammaglobulinemia, patients with more severe B cell defects seemed to experience a milder clinical course.174 , 176 , 181, 182, 183 , 186, 187, 188 Out of the patients described in these reports, there were 10 patients who were asymptomatic (1 with autosomal-recessive agammaglobulinemia, 1 with XLA, and 1 with hypogammaglobuinemia).174 , 176 , 181, 182, 183 , 186, 187, 188 In the international study with 94 patients with PID, 26% had mild disease and were treated outpatient, and the most frequently reported PID in that group was predominantly antibody deficiency with 14 patients.174 There are also reports of patients with XLA who had COVID-19-related pneumonia but not needing mechanical ventilation.174 , 176 , 186 These cases suggest that B cells are important but not strictly required to overcome infection.

In the literature, there have been approximately a dozen reported fatalities after a SARS-CoV-2 infection described in patients with inborn errors of immunity, predominantly in those with antibody deficiencies.174 , 182 , 183 In the international collaboration study, 9 patients in that cohort (7 adults and 2 children) died. All adult patients with PID who died because of SARS-CoV-2 infection had preexisting comorbidities, which included cardiomyopathy, chronic kidney disease, malignancies, chronic lung disease.174 Their PID diagnoses were mostly antibody deficiencies—6 patients with CVID (4), IgG deficiency (1), IgA and IgG2 deficiency (1)—and 1 patient with a syndromic disease.174 The 2 children with X-CGD also had concomitant Burkholderia sepsis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and another child had XIAP deficiency who had severe gut graft vs host disease after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, septic shock, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. There have also been 2 case reports of death in other patients with CVID, including 1 patient who was a 59-year-old woman with chronic bronchitis and CVID on immunoglobulin replacement and the other a 42-year-old man with asthma, morbid obesity, and CVID who was off of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for at least 6 months.182 , 183 The male patient developed COVID-19 pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.183 He was treated with convalescent plasma, remdesivir, and antibiotics for multiple bacterial infections.183 He was found to be severely hypogammaglobulinemic—IgG 117 mg/dL, IgA 10 mg/dL, and IgM undetectable—and received multiple doses of IVIG, but his SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR swabs remained positive throughout his month-long hospitalization before he died.183 Given this patient's poor clinical course and that most other patients with CVID and COVID-19 have received IVIG (83%, 5 out of the 6 patients with CVID in the other case series) recovered, maintaining patients on immunoglobulin replacement could be important during these infections potentially to prevent bacterial suprainfections.181, 182, 183 , 187 , 188 Immunoglobulin replacement has been speculated to potentially be beneficial given its immunomodulatory effects and also potential to provide antibodies that may be cross-reactive with COVID-19, but there are limited data.189 There are many other factors present as well that may increase mortality, including age and comorbidities.

These reports are small and additional studies, and RCTs are needed to evaluate the susceptibility to, clinical course, and optimal treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infections in patients with PID. There are current efforts between allergists and immunologists internationally to gather further data through surveys and databases, and there have been joint society statements, which state that there is no current data pointing to whether there is generally an increased risk of severe COVID-19 in PID.174 , 190 , 191 There may be certain types of PID that are at higher risk of contracting an infection and developing a more severe course, though, and clinician contribution to these studies and the publication of data will be helpful in informing clinical care for patients with PID having COVID-19 because, at this time, there are no formal recommendations for specific therapies in this population.

Diagnosis

The 2 major categories of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics are assays detecting viral nucleic acid and serologic response. Interpretation of results depends on the time test is performed.192

SARS-CoV-2 Nucleic Acid Testing

Viral nucleic acid detection is the mainstay of testing for active infection. There are multiple assays using RT-PCR technology that amplify and detect regions of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Although high in specificity and analytical sensitivity SARS-CoV-2, real-life performance depends on the clinical scenario. False-negative results may arise owing to improper sampling or sampling site. For example, a patient with COVID-19 lower respiratory tract infection may be negative by PCR testing of the upper respiratory tract.193 , 194 For this reason, among symptomatic patients who are either hospitalized or in high-risk settings such as congregate living, 1 or more negative nucleic acid amplification testing (NAATs) may not be able to rule out COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 Serology Testing

Serologic tests detect antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in the blood, with multiple assays developed against different viral epitopes with varying degrees of diagnostic performance. Both IgG and IgM rise approximately 10 to 14 days into the illness.195 Current US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO guidelines recommend against using antibody tests to diagnose individuals with active SARS-CoV-2 infection.196 There are also limited data on whether certain antibodies confer immunity and on the duration of protection of neutralizing antibodies. At this time, serologic testing serves as a public health surveillance tool or as an adjunct to PCR testing for diagnosing active infection.

SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Testing

Tests that identify SARS-CoV-2 antigen can be performed rapidly and serve as a rapid point-of-care assay. However, these assays are typically less sensitive than NAATs, with sensitivity ranging from 0% to 94% with an average of 56%.197 Antigen tests perform best early in the course of infection when viral load is highest and is currently recommended by the WHO when NAAT is unavailable and within the first 5 to 7 days of infection.

SARS-CoV-2 Culture

SARS-CoV-2 viral culture is currently only performed for research purposes.

Treatment and Vaccines

The landscape for therapeutics against COVID-19 has changed dramatically since the beginning of the pandemic. Although supportive care remains a cornerstone of therapy, there are now also targeted therapies with data from RCTs to support their use. Here we summarize treatment options for COVID-19.

Antivirals

Remdesivir is a nucleoside analog that inhibits the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Of note, 2 RCTs revealed a clinical benefit in improving recovery in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.198 , 199 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had granted remdesivir emergency use authorization (EUA), and it has become standard of care in the United States for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients.200 Currently, remdesivir should only be used in hospitalized patients. Although the exact oxygen saturation cutoff for remdesivir use is controversial, it has only been studied in patients with evidence of lower tract respiratory disease from COVID-19.

Although initial uncontrolled trials found a possible benefit for hydroxychloroquine201 multiple RCTs now report no clinical benefit for the treatment of or prophylaxis against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and most also exhibit an increased risk of adverse effects.202, 203, 204, 205 The FDA has revoked its EUA for hydroxychloroquine206 and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) COVID-19 Guidelines recommend against using hydroxychloroquine.207

Protease inhibitors used for human immunodeficiency viruses, in particular lopinavir/ritonavir, were postulated to act against the proteases of SARS-CoV-2 and were used previously to treat SARS and MERS.12 However, randomized control trials have found no benefit of either lopinavir/ritonavir208 or darunavir/cobicistat.209 Corticosteroids should not be used in patients who do not require oxygen.

Immunomodulators

The Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy trial, an RCT of more than 6000 hospitalized patients in the United Kingdom, reported a significant mortality benefit for the use of dexamethasone vs placebo, in particular, those who were mechanically ventilated or on supplemental oxygen; there was no mortality benefit (and a trend toward harm) among patients who did not require oxygen.210 Although there are some caveats to the study, the IDSA guidelines now recommend dexamethasone for hospitalized patients requiring oxygen.207

Convalescent plasma is believed to have both antiviral (by means of neutralizing antibodies) and immunomodulatory effects (by means of neutralization of cytokines/complement and other effects).211 Observational data suggest a possible benefit of convalescent plasma212 , 213 and minimal risk of harm,214 although RCT data are limited.215 More trials are underway, and the IDSA guidelines currently recommend using convalescent plasma only in the context of a clinical trial.217 However, the FDA has issued EUA for convalescent plasma despite the current lack of robust RCT data.216

Tocilizumab is an antibody against the IL-6 receptor that has been used in hopes of dampening the inflammatory response in severe cases of COVID-19. However, a meta-analysis of 7 retrospective studies217 and preliminary data from an RCT218 both reported no clinical benefit. IDSA guidelines recommend using tocilizumab only in the context of a clinical trial.207

Other immunomodulators are currently under investigation, including other cytokine and Janus kinase inhibitors. IFN beta is also being studied and has exhibited some promise as part of combination therapy in small RCTs.219 , 220

There are multiple vaccines in development currently using various platforms, including some which use novel messenger RNA (mRNA) technology.221 , 222 The mRNA vaccines rely on the premise that the mRNA that codes for a viral antigen can be delivered into human cells, which then leads to the production of antigen within the cell and a robust immunogenic response against it.221

Conclusion

A review of the virology, clinical manifestations, and treatment of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 has elucidated the similarities and differences among these infections. Additional data are needed to better understand the impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma, allergy, and PID.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding: The authors have no funding sources to report.

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zumla A., Chan J.F.W., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S.C., Yuen K.-Y. Coronaviruses—drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(5):327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song Z., Xu Y., Bao L. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11(1):59. doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan Y., Zhao K., Shi Z.-L., Zhou P. Bat coronaviruses in China. Viruses. 2019;11(3):210. doi: 10.3390/v11030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L.-F., Shi Z., Zhang S., Field H., Daszak P., Eaton B.T. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1834–1840. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D.S.C., Zumla A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: historical, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(4):869–889. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kindler E., Thiel V., Weber F. Interaction of SARS and MERS coronaviruses with the antiviral interferon response. Adv Virus Res. 2016;96:219–243. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung T.S., Liu D.X. Human coronavirus: host-pathogen interaction. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2019;73:529–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization WHO summary of SARS cases. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table Available at:

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SARS US case report. https://www.cdc.gov/media/presskits/sars/cases.htm Available at:

- 11.Peiris J.S.M., Yuen K.Y., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Stöhr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(25):2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao T.-T., Qian J.-D., Zhu W.-Y., Wang Y., Wang G.-Q. A systematic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus—a possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):556–563. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotten M., Lam T.T., Watson S.J. Full-genome deep sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of novel human Betacoronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(5) doi: 10.3201/eid1905.130057. 736-42B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memish Z.A., Mishra N., Olival K.J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11):1819–1823. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.131172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annan A., Baldwin H.J., Corman V.M. Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(3):456–459. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azhar E.I., El-Kafrawy S.A., Farraj S.A. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2499–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raj V.S., Mou H., Smits S.L. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495(7440):251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu G., Hu Y., Wang Q. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500(7461):227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan J.F.W., Lau S.K.P., To K.K.W., Cheng V.C.C., Woo P.C.Y., Yuen K.-Y. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic Betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(2):465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin H.-S., Kim Y., Kim G. Immune responses to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus during the acute and convalescent phases of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):984–992. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ProMed Mail. Novel coronavirus—Saudi Arabia: human isolate. http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20120920.1302733 Available at:

- 23.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available at:

- 24.World Health Organization MERS global summary and assessment of risk. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326126/WHO-MERS-RA-19.1-eng.pdf?ua=1 Available at:

- 25.Haagmans B.L., Al Dhahiry S.H.S., Reusken C.B.E.M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(2):140–145. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70690-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drosten C., Muth D., Corman V.M. An observational, laboratory-based study of outbreaks of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Jeddah and Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(3):369–377. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assiri A., McGeer A., Perl T.M. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter J.C., Nguyen D., Aden B. Transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in health care settings, Abu Dhabi. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(4):647–656. doi: 10.3201/eid2204.151615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killerby M.E., Biggs H.M., Midgley C.M., Gerber S.I., Watson J.T. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(2):191–198. doi: 10.3201/eid2602.190697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J.-E., Jung S., Kim A., Park J.-E. MERS transmission and risk factors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):574. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S.W., Park J.W., Jung H.-D. Risk factors for transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection during the 2015 outbreak in South Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(5):551–557. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alraddadi B.M., Al-Salmi H.S., Jacobs-Slifka K. Risk factors for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection among health care personnel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(11):1915–1920. doi: 10.3201/eid2211.160920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virlogeux V., Fang V.J., Park M., Wu J.T., Cowling B.J. Comparison of incubation period distribution of human infections with MERS-CoV in South Korea and Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35839. doi: 10.1038/srep35839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: severe respiratory illness associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)--worldwide, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(23):480–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from persons under investigation (PUIs) for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—version 2.1. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html Available at:

- 36.Omrani A.S., Saad M.M., Baig K. Ribavirin and interferon alfa-2a for severe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(11):1090–1095. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arabi Y.M., Shalhoub S., Mandourah Y. Ribavirin and interferon therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome: a multicenter observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(9):1837–1844. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arabi Y.M., Mandourah Y., Al-Hameed F. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(6):757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Doremalen N., Falzarano D., Ying T. Efficacy of antibody-based therapies against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in common marmosets. Antiviral Res. 2017;143:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houser K.V., Gretebeck L., Ying T. Prophylaxis with a Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)-specific human monoclonal antibody protects rabbits from MERS-CoV infection. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(10):1557–1561. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corti D., Zhao J., Pedotti M. Prophylactic and postexposure efficacy of a potent human monoclonal antibody against MERS coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):10473–10478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510199112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu L., Liu Q., Zhu Y. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3067. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Graham R.L. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(396) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(1022 4):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau S.K.P., Luk H.K.H., Wong A.C.P. Possible bat origin of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1542–1547. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;588(7836):E6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atri D., Siddiqi H.K., Lang J.P., Nauffal V., Morrow D.A., Bohula E.A. COVID-19 for the cardiologist: basic virology, epidemiology, cardiac manifestations, and potential therapeutic strategies. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(5):518–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L.C., Lely A.T., Navis G.J., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu H., Zhong L., Deng J. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.-C. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181(5):1036–1045.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization WHO statement regarding cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-of-pneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china Available at:

- 53.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(1022 3):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(1022 9):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 hospitalization and death by age. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html Available at: