Abstract

After the closure of pill mills and implementation of Florida’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program in 2010, high demand for opioids was met with counterfeit pills, heroin, and fentanyl. In response, medical students at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine embarked on a journey to bring syringe services programs (SSPs) to Florida through an innovative grassroots approach. Working with the Florida Medical Association, students learned patient advocacy, legislation writing, and negotiation within a complex political climate. Advocacy over 4 legislative sessions (2013–2016) included committee testimony and legislative visit days, resulting in the authorization of a 5-year SSP pilot.

The University of Miami’s Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) SSP opened on December 1, 2016. Students identified an urgent need for expanded health care for program participants and founded a weekly free clinic at the SSP. Students who rotate through the clinic learn medicine and harm reduction through the lens of social justice, with exposure to people who use drugs, sex workers, individuals experiencing homelessness, and other vulnerable populations. The earliest success of the IDEA SSP was the distribution of over 2,000 boxes of nasal naloxone, which the authors believe positively contributed to a decrease in the number of opioid-related deaths in Miami-Dade County for the first time since 2013. The second was the early identification of a cluster of acute human immunodeficiency virus infections among program participants.

Inspired by these successes, students from across the state joined University of Miami students and met with legislators in their home districts, wrote op-eds, participated in media interviews, and traveled to the State Capitol to advocate for decisive action to mitigate the opioid crisis. The 2019 legislature passed legislation authorizing SSPs statewide. In states late to adopt SSPs, medical schools have a unique opportunity to address the opioid crisis using this evidence-based approach.

Before 2010, thousands of Americans would make regular trips down Interstate 95, the “Oxy Express,” to travel to Florida to visit unscrupulous pain management clinics, otherwise known as pill mills. In 2010, legislators in the state enacted legislation to close those clinics and implement the state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, abruptly cutting the supply of opioids without addressing demand, significantly contributing to the modern-day opioid crisis.

High demand for opioids was met briskly with counterfeit pills, followed by cheap heroin, and ultimately the deadly transition to fentanyl. This drug use occurred in a state with a notoriously unmitigated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, especially in the city of Miami, which from 2015 to 2018 has consistently ranked first in HIV incidence nationwide and which had a rate of 42.9 new cases per 100,000 residents in 2018.1–4 Absent from Florida and illegal in much of the southern United States was one of the cornerstones of HIV prevention—syringe services programs (SSPs). As the opioid crisis worsened and communities sought ways to curb overdoses and respond to HIV outbreaks associated with injection drug use,5–9 medical students at our institution, the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, embarked on a journey to bring SSPs to Florida through an innovative grassroots approach.

Collecting the Baseline Data: Collaboration and Grassroots Efforts

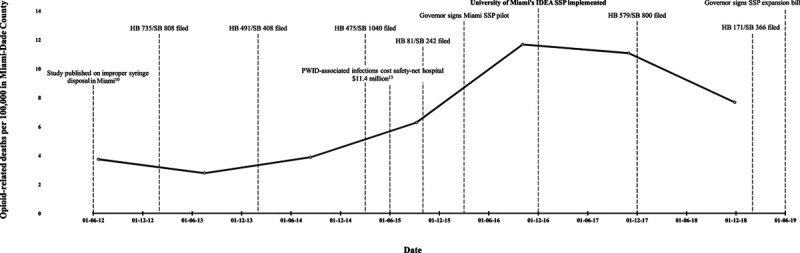

In 2008, the Harm Reduction Coalition held its national conference in Miami, Florida. After this meeting, a collaboration between students and researchers from San Francisco and the University of Miami developed, resulting in a capstone project focused on the comparison of syringe disposal practices in a city with SSPs and one without SSPs. The study, which was published in 2012 (see Figure 1), revealed that without venues for proper disposal, Miami had 8 times the number of syringes on its streets than San Francisco, which had 4 large harm reduction programs distributing over 2 million syringes annually.10 This result, featured on the front page of the Miami Herald and disseminated via media outlets, served as a catalyst for a student-led movement to bring SSPs to Florida.

Figure 1.

Timeline of syringe services programs (SSPs) legislation in Florida. Data on opioid-related deaths were provided to the authors by the Florida Department of Children and Families. Dates are given in day-month-year format. Abbreviations: HB, House bill; SB, Senate bill; PWID, persons who inject drugs; IDEA, Infectious Disease Elimination Act.

The Journey From the Capstone Project to Legislative Action

Energized by the study’s findings and the concerns of the community, a group of medical students crafted and presented a resolution on behalf of the Medical Student Section at the 2012 Florida Medical Association (FMA) Annual Meeting. This resolution sought to harness the power of organized medicine and challenged the FMA to seek legislation to authorize SSPs in Florida. Despite a sharp divide within the FMA, the students ultimately gained the FMA’s support, using an evidence-based argument in their testimony. While tremendous student energy went into the adoption of the resolution, the fight within the FMA was minor compared with what lay ahead in the capitol.

Having garnered the support of the FMA in Tallahassee, under its tutelage, our students had an experiential crash course in advocacy, legislation writing, and negotiation within a complex political climate—all hallmarks of the legislative process, which is sometimes referred to as “sausage making” by our state legislators. Our students’ initial approach was built on the pillars of public education and coalition building.11 Public education efforts consisted of op-eds written by students with our faculty, as well as television and radio interviews. The students also used social media to send action alerts and to coordinate with students and residents from other medical schools in the state. As a result of the public education efforts, the coalition was fortified as Miami’s state attorney, police chiefs, hospitals, county medical society, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) service organizations joined University of Miami students and faculty in pursuit of the evidence-based HIV prevention intervention of SSPs.12

Over 4 legislative sessions (2013–2016), our students were joined by other medical students and residents from across the state in seeking authorization of SSPs in Florida. Advocacy included testimony in each committee of reference, as well as medical student and resident legislative visit days, in coordination with the Council of Florida Medical School Deans. Students quickly learned that a multipronged approach was most effective. That is, despite the humanitarian argument and scientific evidence, the legislature failed to pass legislation authorizing SSPs during the 2013 and 2014 sessions. Therefore, the students decided to examine the fiscal impact of injection drug use. Their research showed that the annual cost of treating persons who inject drugs at our county safety-net hospital was $11.4 million, due to recurrent bacterial infections.13 These findings, published just after the 2015 legislative session, increased interest in the legislation, which was once again proposed in 2016. While the 2016 legislation gained critical support, official opposition from the Florida Sheriffs Association and the Florida Department of Health led to many concessions in the language of the bill. The resulting proposal was an unfunded 5-year SSP pilot program run by the University of Miami. Despite the limitations of this legislation, in 2016, 3 years after the initial attempt to legalize SSPs, the Florida Legislature authorized the Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA), establishing the Miami SSP pilot. The name IDEA was both a reflection of the power of a student idea and important for effective branding, as it helped to reduce the stigma associated with the legislation.

Moving IDEA Forward and Expanding Its Reach

Following the passage of the bill, the University of Miami moved expeditiously to lead the state’s evidence-based response to the opioid crisis by starting the SSP pilot. National organizations, such as the Harm Reduction Coalition and AIDS United, provided capacity building assistance in the form of community education and operating procedures, leading to the opening of the University of Miami’s IDEA SSP on December 1 (World AIDS Day), 2016. Offering new syringes and injection equipment, HIV and hepatitis C screenings, and referrals for health care and drug treatment, the IDEA SSP began extensive outreach to the most marginalized community in Miami-Dade County—people who inject drugs.

The students identified an urgent need for expanded health care for participants in the IDEA SSP—a group that had suffered decades of stigma surrounding their injection drug use and that was reluctant to enter the traditional health care system. Buttressed by the central tenets of harm reduction and meeting people where they are, the students founded a weekly free clinic at the SSP through the University of Miami’s Department of Community Service. This clinic, called the IDEA Clinic, offers primary care as well as on-site wound care and is staffed by University of Miami faculty and Jackson Memorial Hospital surgery, emergency medicine, dermatology, and internal medicine residents. The clinic provides an opportunity for students to learn about health care for people who use drugs directly from the patients themselves. Our faculty and residents use a “street medicine” approach (the fundamental underpinning of which is to meet people experiencing homelessness where they are and on their own terms to reduce harm) that is already helping to break the cycle of learned stigma in our health care system as evidenced by the growing success of the clinic.14 Most importantly, our students who rotate through the IDEA Clinic learn medicine and harm reduction through the lens of social justice, with exposure to people who use drugs, sex workers, individuals experiencing homelessness, and other vulnerable populations. What began as a much-needed harm reduction program has quickly evolved; via proactive beneficence amplification, the students have integrated primary care and onsite wound care into their expanded harm reduction framework.

Exemplifying our research mission at the University of Miami, the IDEA SSP’s database has inspired translational research with direct policy implications. For example, in collaboration with students from the University of Miami’s Department of Public Health Sciences, our students have conducted follow-up studies to show the efficacy of the pilot8,15–17 and presented their findings at numerous national conferences (e.g., the Society of Student Run Free Clinics Annual Conference, Fast-Track Cities conference, International Conference on Hepatitis Care in Substance Users, College on Problems of Drug Dependence Meeting, American Medical Student Association Annual Convention, American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, and National Harm Reduction Conference).

IDEA: Initial Outcomes and Further Advocacy

The transition to heroin and introduction of fentanyl into the drug supply sharply increased the number of opioid-related deaths in Florida from 1,930 to 4,279 between 2012 and 2017.18 In response, the University of Miami’s IDEA SSP partnered with the Florida Department of Children and Families in the first street-level distribution of nasal naloxone to people who use drugs in the state. The earliest success of the IDEA SSP was the distribution of over 2,000 boxes of nasal naloxone in the first 2 years of operation, which we believe positively contributed to a decrease in the number of opioid-related deaths in Miami-Dade County for the first time since 2013 (see Figure 1).

Under a student-initiated grant funded by the Gilead Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) program, we implemented routine, opt-out, anonymous HIV and hepatitis C screenings at the SSP. This initiative provided the IDEA SSP’s second success, enabling the early identification of a cluster of acute HIV infections among program participants in 2018. Collaboration with key stakeholders (e.g., the Florida Department of Health) led to rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy with significantly reduced barriers to treatment. Rapid viral suppression was achieved in all 7 patients with acute HIV infection, and our students had the unique opportunity to participate in an outbreak investigation in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Florida Department of Health. Thus, the routine screenings and intensive patient navigation provided at the IDEA SSP averted an HIV outbreak in Miami in 2018.8

Additionally, as of December 2019, 40 faculty rotating through the IDEA Clinic have instructed 220 student volunteers on the principles of harm reduction and compassionate medicine since the clinic’s opening in August 2017, and there have been 96 clinic nights and 222 patients served.

Inspired by IDEA SSP’s early successes, our medical and public health students rallied again, under the mentorship of the faculty who had advocated for the pilot, to campaign for the statewide adoption of SSPs. Students found sponsors to introduce legislation to authorize SSPs statewide. Following the blueprint from the passage of the pilot program, medical students from across the state learned from their colleagues at the University of Miami and advocated for their patients who had been neglected by the health care system. This advocacy included meeting with legislators in their home districts, writing op-eds, participating in media interviews, and traveling to the State Capitol. During the 2019 legislative session, the coalition presented a united front as the Miami mayor, police chief, state attorney, Department of Health, and mothers of addicted children hailed the program’s success. Urged by medical students and the coalition to act decisively to mitigate the opioid crisis, the 2019 Florida Legislature passed legislation authorizing SSPs statewide, including at all 10 medical colleges in the state.

What began as a student capstone project has over the course of a decade led to the first evidence-based legislation to address the state’s opioid crisis. Other measures passed by the legislature over the same time frame, such as a 3-day limit on opioid prescriptions for acute pain (2018 HB 21),19 sought to decrease supply as was done with the implementation of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program; such nonevidence-based strategies have the potential to cause the same harms seen following the closure of the pill mills. Focusing on evidence-based harm reduction strategies, such as the authorization of SSPs, will allow the community to approach people who use drugs with compassion and dignity. Like their faculty experienced during the HIV epidemic, our students are on the front lines of a crisis that has killed more people in the United States in 1 year than HIV did at its height.20 Importantly, the students were empowered to use their platform as future leaders to advocate for patients who often live on the margins of society.

Next Steps

Across Florida, organizations now have the opportunity to establish SSPs, and many medical schools are seeking to replicate the University of Miami model. In states late to adopt SSPs, medical schools have a unique opportunity to address the opioid crisis using this evidence-based approach. Medical schools can have an immediate and lasting impact on eliminating preventable overdose deaths and infectious diseases by supporting student advocacy and innovation. To reach the CDC’s goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030,21 the medical profession must use all HIV prevention tools in its armamentarium.

The Students’ Legislative Tool Kit

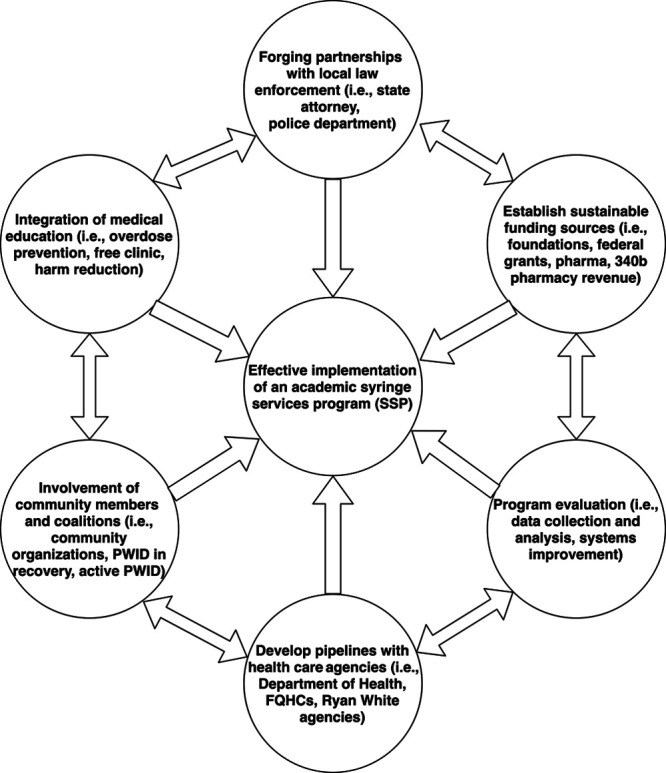

For medical schools looking to open SSPs, it is important for students to identify a faculty champion, engage government affairs to address local policy, and engage the communications department for community education. The university must identify resources (e.g., in Miami, renovated, low-cost shipping containers were placed on a plot of university-owned land in the health district) and leverage opportunities to develop fundraising and grant writing skills. Diverse funding pathways—including state and municipal budget allocations, HIV/AIDS foundations (e.g., MAC AIDS Fund, Elton John AIDS Foundation, AIDS Healthcare Foundation), the Gilead FOCUS program, the pharmaceutical industry, 340b pharmacy revenue, and federal grants under the CDC’s Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative—should be considered (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blueprint for effective implementation of an academic syringe services program (SSP). Abbreviations: Pharma, pharmaceutical industry; PWID, persons who inject drugs; FQHCs, federally qualified health centers.

Medical schools have a unique capability to conduct implementation science research and innovatively enhance SSPs. Our IDEA SSP recently won 2 Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative planning grants to design a telemedicine test and treat program for antiretroviral initiation and a mobile pre-exposure prophylaxis and buprenorphine induction program targeted to the Black community. The blueprint for opening an effective academic SSP outlined in Figure 2 can unite rigorous research, innovative education, and program evaluation with diverse and meaningful community partnerships leading to the integration of evidence-based medicine into both medical school curricula and public health practice.

Finally, at the University of Miami, under our State Opioid Response grant from the Florida Department of Children and Families, we are implementing an integrated opioid education curriculum for all of our medical students. The cornerstone experiences of the curriculum include a harm reduction minirotation through the IDEA SSP. Our hope is to address and mitigate the endemic stigma against people who use drugs within the health care system. Every student will also rotate through our outpatient medication-assisted treatment clinic and receive training equivalent to a buprenorphine waiver. This will commence with buprenorphine training for our faculty and residents. The curriculum will also include an advocacy component, in which our students will again unite to seek authorization or legislation allowing them to prescribe buprenorphine in-state without a waiver, similar to advocacy efforts that are currently underway in Rhode Island. The road to meaningful impact on the opioid crisis can be long, but our experience demonstrates that medical students can use innovative grassroots approaches to make important strides.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to this work: Lisa Rosen-Metsch, David Forrest, Austin Coye, Kasha Bornstein, and the Infectious Disease Elimination Act syringe services programs staff.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The advocacy detailed in this article was funded by AIDS United’s Syringe Access Fund. Research reported in this article was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA240139.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Disclaimers: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data: The data on opioid-related deaths (see Figure 1) were provided by the Florida Department of Children and Families.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2017. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; Vol. 29. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2017-vol-29.pdf. Published November 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (Updated). HIV Surveillance Report, 2018; Vol. 31. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; Vol. 27. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2016. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; Vol. 28. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 5.Golden MR, Lechtenberg R, Glick SN, et al. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs—Seattle, Washington, 2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: An outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020; 110:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cranston K, Alpren C, John B, et al. Notes from the field: HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs—Northeastern Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68:253–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tookes H, Bartholomew TS, Geary S, et al. Rapid identification and investigation of an HIV risk network among people who inject drugs—Miami, FL, 2018. AIDS Behav. 2020; 24:246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, et al. ; Indiana HIV outbreak investigation team. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tookes HE, Kral AH, Wenger LD, et al. A comparison of syringe disposal practices among injection drug users in a city with versus a city without needle and syringe programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012; 123:255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbour K, McQuade M, Brown B. Students as effective harm reductionists and needle exchange organizers. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2017; 12:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley SF, Jolley DJ, Kaldor JM. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. Lancet. 1997; 349:1797–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tookes H, Diaz C, Li H, Khalid R, Doblecki-Lewis S. A cost analysis of hospitalizations for infections related to injection drug use at a county safety-net hospital in Miami, Florida. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0129360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginoza MEC, Tomita-Barber J, Onugha J, et al. Student-run free clinic at a syringe services program, Miami, Florida, 2017–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020; 110:988–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartholomew TS, Tookes HE, Bullock C, Onugha J, Forrest DW, Feaster DJ. Examining risk behavior and syringe coverage among people who inject drugs accessing a syringe services program: A latent class analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2020; 78:102716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyengar S, Kravietz A, Bartholomew TS, Forrest D, Tookes HE. Baseline differences in characteristics and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs by syringe exchange program modality: An analysis of the Miami IDEA syringe exchange. Harm Reduct J. 2019; 16:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine H, Bartholomew TS, Rea-Wilson V, et al. Syringe disposal among people who inject drugs before and after the implementation of a syringe services program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019; 202:13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Drugs identified in deceased persons by Florida medical examiners: 2018 annual report. https://www.fdle.state.fl.us/MEC/Publications-and-Forms/Documents/Drugs-in-Deceased-Persons/2018-Annual-Drug-Report.aspx. Published November 2019. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 19.Florida Senate. CS/CS/HB 21—Controlled substances. https://www.flsenate.gov/Committees/BillSummaries/2018/html/1799. Published 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 20.DeWeerdt S. Tracing the US opioid crisis to its roots: Understanding how the opioid epidemic arose in the United States could help to predict how it might spread to other countries. Nature. 2019; 573(suppl):S10–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for America. https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/index.html. Published 2019. Accessed June 17, 2020.