Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: extracellular fluid; heart; microscopy, electron; myocyte, cardiac; sarcolemma

Rationale:

The sarcolemma of cardiomyocytes contains many proteins that are essential for electromechanical function in general, and excitation-contraction coupling in particular. The distribution of these proteins is nonuniform between the bulk sarcolemmal surface and membrane invaginations known as transverse tubules (TT). TT form an intricate network of fluid-filled conduits that support electromechanical synchronicity within cardiomyocytes. Although continuous with the extracellular space, the narrow lumen and the tortuous structure of TT can form domains of restricted diffusion. As a result of unequal ion fluxes across cell surface and TT membranes, limited diffusion may generate ion gradients within TT, especially deep within the TT network and at high pacing rates.

Objective:

We postulate that there may be an advective component to TT content exchange, wherein cyclic deformation of TT during diastolic stretch and systolic shortening serves to mix TT luminal content and assists equilibration with bulk extracellular fluid.

Methods and Results:

Using electron tomography, we explore the 3-dimensional nanostructure of TT in rabbit ventricular myocytes, preserved at different stages of the dynamic cycle of cell contraction and relaxation. We show that cellular deformation affects TT shape in a sarcomere length-dependent manner and on a beat-by-beat time-scale. Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching microscopy, we show that apparent speed of diffusion is affected by the mechanical state of cardiomyocytes, and that cyclic contractile activity of cardiomyocytes accelerates TT diffusion dynamics.

Conclusions:

Our data confirm the existence of an advective component to TT content exchange. This points toward a novel mechanism of cardiac autoregulation, whereby the previously implied increased propensity for TT luminal concentration imbalances at high electrical stimulation rates would be countered by elevated advection-assisted diffusion at high mechanical beating rates. The relevance of this mechanism in health and during pathological remodeling (eg, cardiac hypertrophy or failure) forms an exciting target for further research.

Meet the First Author, see p 153

The core function of cardiomyocytes, generation of force and shortening, is achieved by electrically controlled cyclic alterations in cytosolic calcium concentration and subsequent changes in actin-myosin cross-bridge interactions—a process referred to as excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). Although beat-by-beat dynamics of cardiac ECC have been extensively studied at whole organ, tissue, and cell levels, time-resolved nanoscopic changes of membrane domains relevant for ECC are ill-explored.

The rapid, efficient, and near-synchronous activation of intracellular contractile units of a cardiomyocyte depends, across mammalian species and both in ventricular and in atrial cells,1–3 on the presence of a network of membrane invaginations—transverse tubules (TT), extending from the surface sarcolemma to the cells’ center. The TT network is complex and polymorphic, with individual TT diameters ranging from 100 to 400 nm.4,5 Factors such as tortuosity, presence of varicosities and axial connections, and structural obstructions including species-dependent differences in TT mouth configuration,6,7 contribute to diffusion restrictions inside the TT lumen.6,8–10 Accordingly, diffusion inside TT is thought to be 2 to 12 times slower than in bulk extracellular space.9,11–14

The TT network comprises 30% to 60% of total cardiomyocyte surface membrane. It is physically and electrically continuous with the surface sarcolemma. TT luminal content is thus extracellular. TT membranes contain multiple ion channels and transporters underlying ECC, including L-type Ca2+ channels and Na+-Ca2+ exchangers, as well as a host of other voltage-, ligand-, and mechano-gated ion flux pathways.15,16 A majority (60%–80%) of L-type Ca2+ current (trigger for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release) is thought to flow across TT membranes, as evidenced in electrophysiological13,17–21 and immunohistochemical16,22 studies. Studies of the distribution of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (the main pathway for removal of trigger-Ca2+)21,23–30 and the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase also indicate preferential localization in TT.29 This inhomogeneity in the density of ion flux pathways in TT versus surface sarcolemmal membranes gives rise to the possibility for regionally inhomogeneous ion fluxes into and out of the cell, which may be further compounded by different kinetics, for example, of Ca2+ entry and extrusion pathways (the former being rapid, the latter slower and heavily influenced by intracellular Ca2+ concentration).31

Indeed, regionally inhomogeneous Ca2+ influx and extrusion,32 coupled with restricted diffusion within TT, can give rise to the emergence of microdomains of TT ion concentrations that differ from bulk extracellular space, in particular at high pacing rates. Previous studies, conducted using double barreled Ca2+-selective microelectrodes, have shown that extracellular Ca2+ concentration decreases by 2% to 3% during each beat of rabbit papillary muscle, presumably as a consequence of Ca2+ uptake by cardiac cells.33,34 Computational modeling of local changes in Ca2+ diffusion, incorporating single channel characteristics as well as geometric constrains of the TT, suggested that the depletion of Ca2+ (both free and sarcolemma- or glycocalyx-bound) inside the TT would be more pronounced than that in bulk extracellular space—with the model predicting up to 90% depletion in the vicinity of individual L-type Ca2+ channels during each beat.35 Similarly, Ca2+ or K+ depletion have been proposed to occur in frog skeletal muscle TT during membrane de- or hyperpolarization, respectively.36,37

Any changes in the concentration of ions relevant for ECC would increase in a use-dependent manner, that is, rise with pacing rate, potentially causing a gradual Ca2+ depletion of TT content, with the potential for detrimental effects on cardiac function.9,12,15,38 Possible functional consequences of TT luminal ion concentration gradients include the following: (1) alterations in regionally effective action potential duration,39 (2) disturbed Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels, and (3) disturbance of systolic Ca2+ transients, which could (4) interfere with homogeneous contractile activity.9,15,40

Based on 2-dimensional electron microscopy of cardiac tissue, fixed in different contraction states, we previously suggested that TT deform during the contraction-relaxation cycle in a way that may give rise to mechanically assisted diffusion between TT and bulk extracellular space.12 Further evidence on sarcomere length (SL)-dependent changes in TT shape has subsequently been provided, based on 3-dimensional (3D) confocal light microscopy.38,41 However, observations to date have been limited by the nature of samples (using static deformation during chemically induced contracture or passive stretch by intracardiac volume loading) and—for 3D fluorescence microscopy observations—by the spatial resolution of data (image voxel volume >>106 nm3). This restricts spatial insight and leaves unanswered the question as to whether or not mechanically induced TT deformation is present, beat-by-beat, in contracting cardiomyocytes. If yes, such cyclic deformation could drive mechanically assisted TT content exchange and represent a hitherto underappreciated mechanism of TT content homeostasis, with potential autoregulatory relevance in settings where demand (ie, heart rate and/or extent of per-beat deformation) is elevated.

Using a combination of 3D electron tomography structural reconstructions (with voxel sizes of ≈100 nm3) of TT in cardiac cells and tissue, and live cell fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) functional observations of TT content exchange dynamics in rabbit left ventricular cardiomyocytes, we present evidence that confirms (1) the existence of cyclic TT deformation on a beat-by-beat time-scale and (2) the presence of an advective contribution to TT content exchange in cyclically contracting cardiomyocytes.

Methods

All investigations reported in this article conformed to the UK Home Office guidance on the Operation of Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 and to German (TierSchG and TierSchVersV) animal welfare laws, compatible with the guidelines stated in Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, and they were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in Germany (Regierungspräsidium Freiburg, X-16/10R). Animal housing and handling was conducted in accordance with good animal practice, as defined by the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Association, FELASA. No animals were excluded from the analyses.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Sample Preparation for Electron Tomography: Static Samples

For intact tissue studies, New Zealand White rabbit hearts (N=7, female, aged 9 to 11 weeks, fed SDS Standard Diet and maintained on ALPHA-Dri bedding; both LBS Biotech, Horley, United Kingdom) were excised after euthanasia (ear vein injection of thiopental, 50 mg/kg body weight) and swiftly Langendorff-perfused with Krebs-Henseleit solution (containing [in mM]: NaCl 118, KCl 4.75, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 24.8, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, glucose 11, insulin 10 U/L; pH 7.4, bubbled with carbogen [5% CO2 in O2]). After a 5-minute wash of the coronary circulation, hearts were subjected to one of the following: (1) cardioplegic arrest, using a high-K+ version of Krebs-Henseleit solution (KCl 25 mmol/L, NaCl 98 mmol/L); (2) cardioplegic arrest, with concurrent inflation of a left ventricular balloon (25 mm Hg intraventricular pressure) to elicit stretch; or (3) contracture, caused by perfusion with a Li+-for-Na+ substituted version of Krebs-Henseleit solution, supplemented with 10 mmol/L caffeine. All solutions were tightly controlled for iso-osmolality (295–305 mOsm; Semi-Micro Osmometer, Kanuer AG, Berlin, DE) to exclude differential tissue swelling in the 3 study arms (as confirmed by assessment of mitochondrial shape and size; Online Figure VII). As soon as the desired mechanical state was reached, typically within 2 to 3 minutes (hence reference to static deformation), hearts were coronary perfusion-fixed with iso-osmotic Karnovsky’s fixative (3:1:1 mix of sodium cacodylate: paraformaldehyde: glutaraldehyde, ≈300 mOsm; Solmedia Limited, Shrewsbury, United Kingdom). Tissue fragments were excised from the left ventricle and processed for embedding in Epon-Araldite resin, as described previously.42

Sample Preparation for Electron Tomography: Dynamic Samples

For dynamically contracting isolated cardiomyocyte studies, New Zealand White rabbit hearts (N=2, female, age 10 weeks, fed Altromin 2123 diet, Altromin, Lage, DE; maintained on Aspen bedding; Tapvei, Kiili Harjumaa, Estonia), excised as stated above, were used to isolate cells, as described in detail before.43 After isolation and recovery to appropriate Ca2+ levels (1.8 mmol/L), cells were transferred to high-pressure freezing (HPF) buffer, containing [in mM]: NaCl 137, KCl 4, HEPES 10, CaCl2 1.8, creatine 10, taurine 20, adenosine 5, L-carnitine 2, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, insulin 10 U/L; pH 7.4, 300 mOsm, supplemented immediately before use with 10% BSA as a cryoprotectant. Cells were placed inside the HPF chamber of a system with in-chamber electrical stimulation capacity for samples (EM ICE, Leica Microsystems, Vienna, Austria). Sample carrier stack assembly was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells inside the freezing chamber were electrically stimulated (1 Hz, pulse duration 5 ms), and HPF-preserved at prespecified time intervals following the tenth stimulus (poststimulation delays assessed: 15, 55, 105, 155, 205, 305, 505 ms). During HPF, samples are exposed, within 10 ms, to a temperature reduction to −196 °C and a pressure increase to 2×105 kPa (≈2,000 atm), giving rise to instantaneous sample preservation in a process called vitrification (direct transition of liquid water into a solid amorphous glass [Latin: vitrum], without formation of ice crystals). Vitrified samples were freeze-substituted in 1% osmium tetroxide/0.1% uranyl acetate in acetone and processed to Epon-Araldite resin as described before.7 For the relationship between HPF-delay, relative to electrical stimulation, and SL—see Online Figure IIA.

Electron Tomography

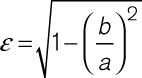

Semi-thick (280 nm) sections were prepared and imaged by dual-axis electron tomography, as described before (isotropic voxel size [1.206 nm]3).42 Imaging was performed at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) Heidelberg; and at Boulder Electron Microscopy Services of the University of Colorado at Boulder. Image reconstruction and segmentation were conducted using IMOD software.42,44 Shape and orientation of individual TT segments were quantified by, first, establishing TT segment long axis (including only TT for which a ≥250 nm long portion could be reconstructed), then identifying an axis-perpendicular cross-sectional plane, and finally fitting each resultant TT cross-section membrane model with an equivalent ellipse, before extracting the eccentricity ε of the ellipse (see Equation 1, where a=length of the major, and b=length of the minor axis; ε-values range from 0 for a perfect circle to 1 for an apparent straight line).

|

(1) |

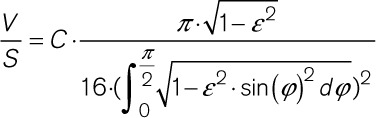

For theoretical assessment of eccentricity-dependent changes in volume:surface ratio, we modeled TT as maintaining an elliptic cross-section during deformation, according to

|

(2) |

where V=TT volume, S=TT surface, C=TT circumference, and ε=eccentricity (S and C were assumed to be constant to reflect the nonstretchable nature of lipid bilayer).

We further identified the smallest angle, α, between the extrapolated major axis of the fitted ellipse and the associated Z-disc plane (α-values ranging from 0° for a Z-disc parallel orientation, to 90° for a Z-disc perpendicular orientation).

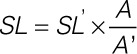

When assessing SL, to avoid artifacts associated with deviations of the plane of imaging from acto-myosin filament lattice orientation (cosine error), SL was established using a proportionality expression (see Equation 3, where SL’=measured apparent distance between Z-discs, A’= measured apparent length of the anisotropic band, A=true length of the anisotropic band).

|

(3) |

The actual length of the A-band was 1.4 µm, established in samples that contained the entire length of individual myosin filaments, whose tomographic volumes were virtually rotated so that the filaments were aligned in parallel to the image analysis plane for direct measurement.

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

FRAP microscopy was performed on rabbit left ventricular cardiomyocytes isolated as described above (N=7, mixed sex, age 9–13 weeks, fed Altromin 2123 diet, Altromin, Lage, DE; maintained on Aspen bedding; TAPVEI, Kiili Harjumaa, Estonia), using ≈1 mmol/L of 10 kDa fluorescein-conjugated dextran (Thermo Fisher, MA; estimated Stokes radius: 1.5–2.0 nm) in the bath solution, containing (in mM): NaCl 137, KCl 4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, creatine 10, taurine 20, adenosine 5, L-carnitine 2, glucose 10, insulin 10 U/L; pH 7.4, 300 mOsm. Imaging was performed on an inverted confocal microscope (LSM 510 DUO; Zeiss, Jena, DE) using a C-Apochromat 40×/NA 1.2 water-immersion objective. Samples were illuminated using a 488 nm laser line. Images (50×50 pixels) were acquired at 5.2 frames per second, and FRAP was performed at 100% laser power (5 cycles). Fluorescence recovery was monitored until a plateau was reached (typically 500 to 1,000 frames). To ensure a steady concentration of fluorescent dextran near the cell surface,45 a continuous flow of dextran-containing buffer was applied during all phases of FRAP measurements, using local perfusion (cFlow; Cell MicroControls, Norfolk, VA) coupled to a piezoelectric micropump (mp6; Bartels Mikrotechnik, Dortmund, DE) with an average perfusion rate of 1 mL/minute. Perfusion efficiency was assessed for every cell analyzed by measuring FRAP in the bath in the immediate proximity of the cell. All imaging was performed at room temperature (22 °C), in a field-stimulation chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) with a volume of 0.6 mL (ie, nominally exchanged every 36 seconds).

To assess the effects of static mechanical deformation on apparent speed of TT diffusion, the chamber surface was precoated with laminin and cells were monitored (1) at rest, (2) during contracture (induced by Li+-for-Na+ substitution in the presence of 10 mmol/L caffeine; as done for tissue—see above), or (3) during passive stretch applied using the carbon fiber technique (here, the chamber surface was precoated with poly-hydroxyethyl methacrylate to prevent cell attachment).46 The mechanical state of cells was assessed by measuring the distance between neighboring fluorescently labeled TT, which was assumed to be equal to SL, and which henceforth will be referred to as such.

To assess the effects of dynamic mechanical deformation on apparent speed of TT luminal diffusion, the chamber surface was precoated with laminin, and paired observations were acquired: cells were FRAP imaged either at rest, or during electrical pacing (0.5–1.5 Hz; Myopacer Cell Stimulator; IonOptix, Westwood, MA), with a variable sequence of the 2 conditions.

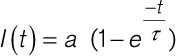

FRAP data were analyzed using a custom Matlab (Natick, MA) script (available from the corresponding author upon request), with a curve fitted following Equation 4 (where I(t)=fluorescence intensity over time, a=mobile fluorescent fraction, t=time, τ=time constant of recovery).

|

(4) |

Within each cell, on average 5 regions of interest (10×10 pixels) were analyzed, and values averaged. As fluorescent recovery time (>103 ms) is much longer than the duration of a single beat (<102 ms), potential measurement artifacts due to cell motion were avoided by excluding systolic frames from FRAP analyses.

Data Analysis

Data are presented as individual points or as mean±SEM, analyzed using Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and Matlab. Data were fitted with linear mixed effects models, taking into account random effects of heart, tissue fragment, and cell for chemically fixed tissue preparation data, and heart and cell for HPF-preserved cell data and FRAP data. F-tests were conducted to assess whether the relationships studied should be fitted with linear, quadratic, or cubic models. The F-statistic was found for each relation and compared with the critical value of the F-distribution for that relation. P values are provided for each graph to indicate whether the fitted model is more suitable than assuming a constant relationship. P<0.05 were taken to indicate a statistically significant difference. Further details of statistical analysis are provided in the individual figure legends. The distribution of data across all samples can be found in Online Tables I and II. Additionally, graphical representation of preparation-related tissue and cell data distribution can be found in Online Figures VIII and IX.

Power analysis was performed a priori to determine anticipated optimal sample size. Experiments were performed in a randomized manner (regarding mechanical state designation), and data analysis was performed blinded (name concealment). Images were chosen for illustration based on the conclusions of the quantitative analysis, to most closely convey numerical results. For further experimental detail, please see the Major Resources Table in the Data Supplement. For further detail about statistical analyses, please see Online Table III.

Results

Shape and Orientation of TT During Static Changes in SL

For the purpose of this investigation, we considered as static all those changes in SL, where the target mechanical state (contracture, rest, stretch) was maintained for ≥102 times the duration of normal contraction cycles. This applies to all chemically fixed samples (see Methods).

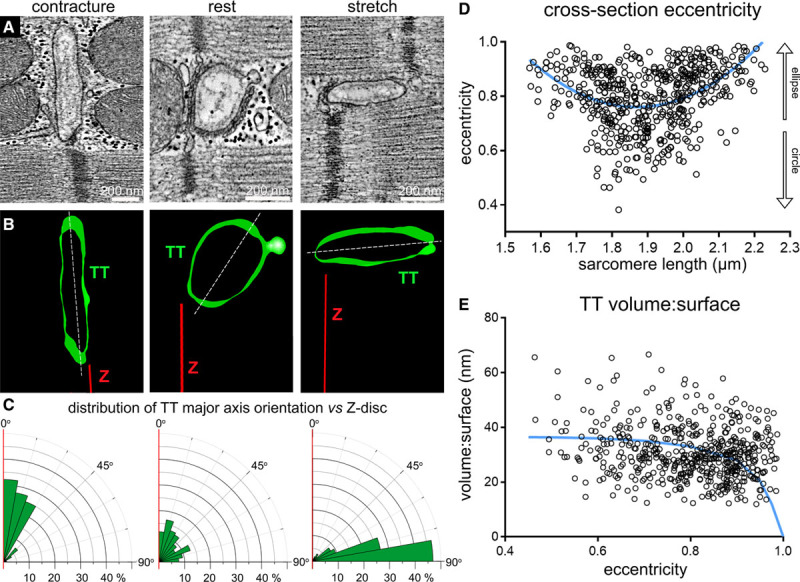

The shape and orientation of TT in chemically fixed left ventricular myocardial tissue, preserved in different mechanical states, was analyzed in 3D electron tomograms. Analysis of cross-sectional shape revealed that TT undergo a biphasic change in eccentricity (ε; a measure of how much a shape deviates from circular, see Equation 1) between the extremes of SL (ranging from <1.6 µm during contracture to >2.2 µm during stretch). Both contracture and stretch are associated with higher eccentricity values, indicating a more elongated TT cross-section, whereas the unloaded state is associated with a more circular shape of TT (Figure 1A through 1D). For alternative representation, eccentricity data are complemented by minor:major radius assessments, shown in the Data Supplement (see Online Figure IA).

Figure 1.

Shape and orientation of transverse tubules (TT) change during static (minutes) alterations of the mechanical state of cardiomyocytes (chemically fixed tissue). A, Representative electron tomography (ET) slices from rabbit ventricular tissue, preserved in contracture (sarcomere length [SL] <1.76 µm), at rest (SL 1.86±0.1 µm), and during stretch (SL >1.96 µm). B, Segmented 3-dimensional TT models, based on ET volumes. Green: TT, red: Z-disc plane, white: TT cross-section major axis. C, Rose plots of the distribution of minimum angle α between TT cross-sectional major axis and Z-disc plane in the 3 mechanical states. Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (Online Figure IB, data assessed using linear regression model); P<0.0001. D, TT cross-section eccentricity as a function of SL. Data were assessed using nonlinear quadratic fit (blue curve). Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (see also Online Figure IA); P<0.0001. E, Volume:surface ratio of TT segments as a function of TT cross-sectional eccentricity. Data fitted with a realistic geometric shape-based model, assuming an elliptical cross-section with constant circumference and volume:surface value of 0 at ε=1 (blue curve, see also Online Figure III). Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (quadratic fit, not shown; see also Online Figure IC); P<0.0001. N=7 hearts/29 tissue samples/125 cells/539 TT (see also Online Table I). P values indicate whether a fitted model is more suitable than assuming a constant relationship.

The orientation of the main cross-sectional axis of TT, relative to the associated Z-discs, changed from TT squeezed near-parallel to neighboring Z-discs in contractured tissue, to TT whose major axis was near-perpendicular to Z-discs in stretched myocardium. At resting SL, there was no clear preference for TT-to-Z-disc orientation angles (Figure 1A through 1C; Online Figure IB).

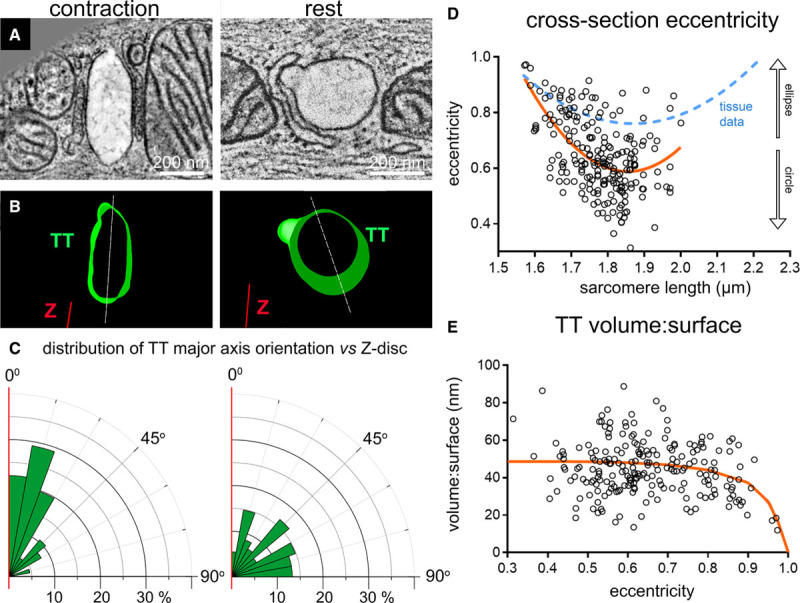

Shape and Orientation of TT During Dynamic Changes in SL (Contraction)

To establish whether the observed structural changes in shape and orientation of TT upon mechanical tissue deformation occur on a beat-by-beat basis, we preserved rabbit left ventricular myocytes using millisecond-accurate, action potential synchronized HPF. SL at rest (before triggered contractions and after relaxation) was 1.78 µm (ranging from 1.64 to 2.05 µm), and at peak contraction (HPF at 105 ms after last electrical stimulation) it was 1.62 µm (ranging from 1.57 to 1.67 µm; Online Figure IIA).

We observed SL-dependent changes in TT shape (eccentricity) and orientation (major axis of TT cross-section, relative to Z-disc) in acutely contracting and relaxing cells (Figure 2A through 2D, Online Figure IIB; for minor:major radius data, see Online Figure IIC) that are consistent with tissue-based static deformation data (note that tissue data includes passive distension to SL that are larger than those present in resting/contracting single cells, preserved by HPF). In general, chemically fixed tissue-based data was found to be biased toward higher eccentricity values, compared with single cell observations (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Shape and orientation of transverse tubules (TT) change during dynamic (milliseconds) cardiomyocyte contraction and relaxation (high-pressure freezing [HPF]-preserved beating cells). A, Representative electron tomography (ET) slices from single cardiomyocytes, HPF-preserved at prescribed intervals after electrical stimulation, here at rest before contraction (sarcomere length [SL]=1.78 µm) and during peak contraction (SL=1.57 µm, HPF timed at 105 ms post-stimulation). B, Segmented 3-dimensional TT models based on ET volumes. C, Rose plots of the distribution of minimum angle α between TT cross-sectional major axis and Z-disc plane in the 2 mechanical states. Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (Online Figure IIB, data assessed using linear regression model); P<0.0001. D, TT cross-section eccentricity as a function of SL. Data were assessed using nonlinear quadratic fit (orange curve). Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (see also Online Figure IIC); P<0.0001. Blue dashed curve shows the equivalent relationship observed for tissue data (from Figure 1D). E, Volume-to-surface ratio of TT segments as a function of TT cross-sectional eccentricity. Data fitted with a realistic geometric shape-based model, assuming an elliptical cross-section with constant circumference and volume:surface value of 0 at ε=1 (orange curve, see also Online Figure III). Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model (linear fit, not shown; see also Online Figure IID); P<0.05. N=2 hearts/16 tissue samples/56 cells/214 TT (see also Online Table II). P values indicate whether a fitted model is more suitable than assuming a constant relationship.

Volume:Surface Ratio of TT at Different SL

As changes in cross-sectional shape of tubular structures alter their volume:surface ratio, we assessed this in TT segments with a minimum length of 250 nm. The highest volume:surface ratios were measured, both in chemically fixed and in HPF-preserved samples, in TT with the lowest eccentricity values (Figures 1E and 2E).

To accommodate the fact that at ε=1 the volume contained in TT would be zero, we used a realistic geometric shape-based approach (here for an elliptical cross-section with constant circumference; Equation 2) to model the expected relationship between volume:surface and eccentricity (Figures 1E and 2E; for minor:major radius data see Online Figures IC and IID). Based on this model, the expected reduction in fractional TT volume between ε=0.45 and ε=0.95 would be 36.2% (Online Figure III; note the superior fit of model predictions with the contraction-cycle synchronized HPF cell data, as opposed to chemically fixed tissue).

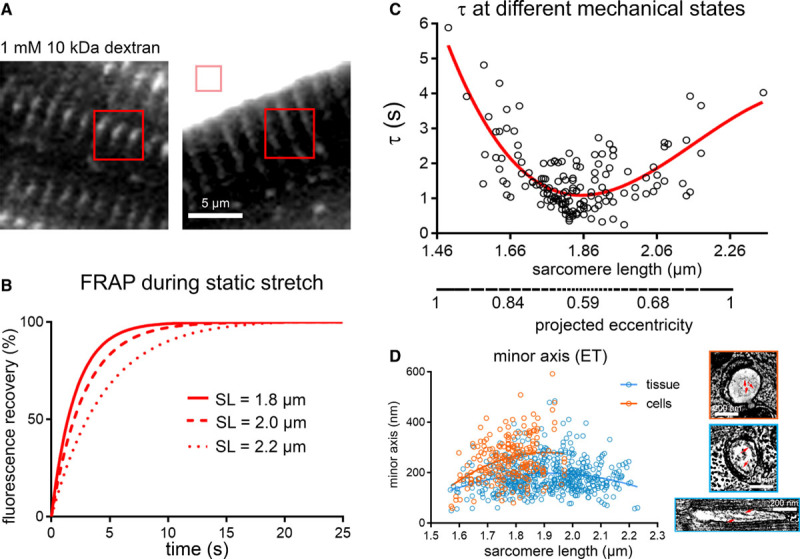

Apparent Speed of TT Diffusion During Static Changes in SL

FRAP microscopy was used to assess the impact of mechanical deformation on the apparent speed of particle movement inside TT (10 kD dextran, stokes radius ≈2 nm). Observations were made in live cells that were arrested in contracture, at rest, or subjected to static stretch using the carbon fiber technique (SL ranged from 1.49 µm in contracture to 2.35 µm during stretch, Figure 3A through 3C). The time constant (τ) of FRAP showed a biphasic relationship with SL: the highest values (indicative of slow diffusion) were seen in cells where static SL was either ≤1.76 or ≥1.96 µm (Figure 3C, Online Figure IVA), where τ is up to 4-fold larger than that of cells with a SL of 1.86±0.1 µm.

Figure 3.

Apparent speed of transverse tubule (TT) luminal diffusion is reduced during static mechanical deformation (live cells). A, Representative fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) bleach regions for TT analysis (red squares) and perfusate control (pink square) relative to a rabbit isolated ventricular cardiomyocyte, incubated with fluorescently tagged dextran. B, Representative fitted FRAP curves, obtained from the same cell during stepwise static stretch-and-hold from a resting sarcomere length (SL) of 1.8, to 2.0, and 2.2 µm. C, Fluorescence recovery times (τ) were the lowest in cells at rest (SL 1.86±0.1 µm, corresponding to lowest TT eccentricity) and rose both during contracture and stretch (ie, with rising TT eccentricity, as extrapolated from electron tomography [ET] data, see also Online Figure IV). Data were assessed using a nonlinear cubic regression fit (red curve). Statistical significance was assessed comparing a mixed effects model to a constant model; P<0.001. P value indicates whether a fitted model is more suitable than assuming a constant relationship. N=7 hearts/89 cells. D, Minor TT axis at different SL as measured in chemically fixed tissue (blue) and high-pressure freezing-preserved cells (orange) ET data. Additional structural restrictions to diffusion are predicted to arise from the presence of glycocalyx in TT (right, red arrows, see also Online Figure V). N=7 hearts/29 tissue samples/125 cells/539 TT (tissue, see also Online Table I) and N=2 hearts/16 tissue samples/56 cells/214 TT (cells, see also Online Table II).

One of the factors limiting diffusion at high eccentricities (Online Figure IVB) is thought to be the minimum TT cross-sectional axis (Figure 3D), whose reduction is further exacerbated by the presence of glycocalyx with a radial thickness of 35 to 50 nm (Figure 3D inserts, Online Figure V).

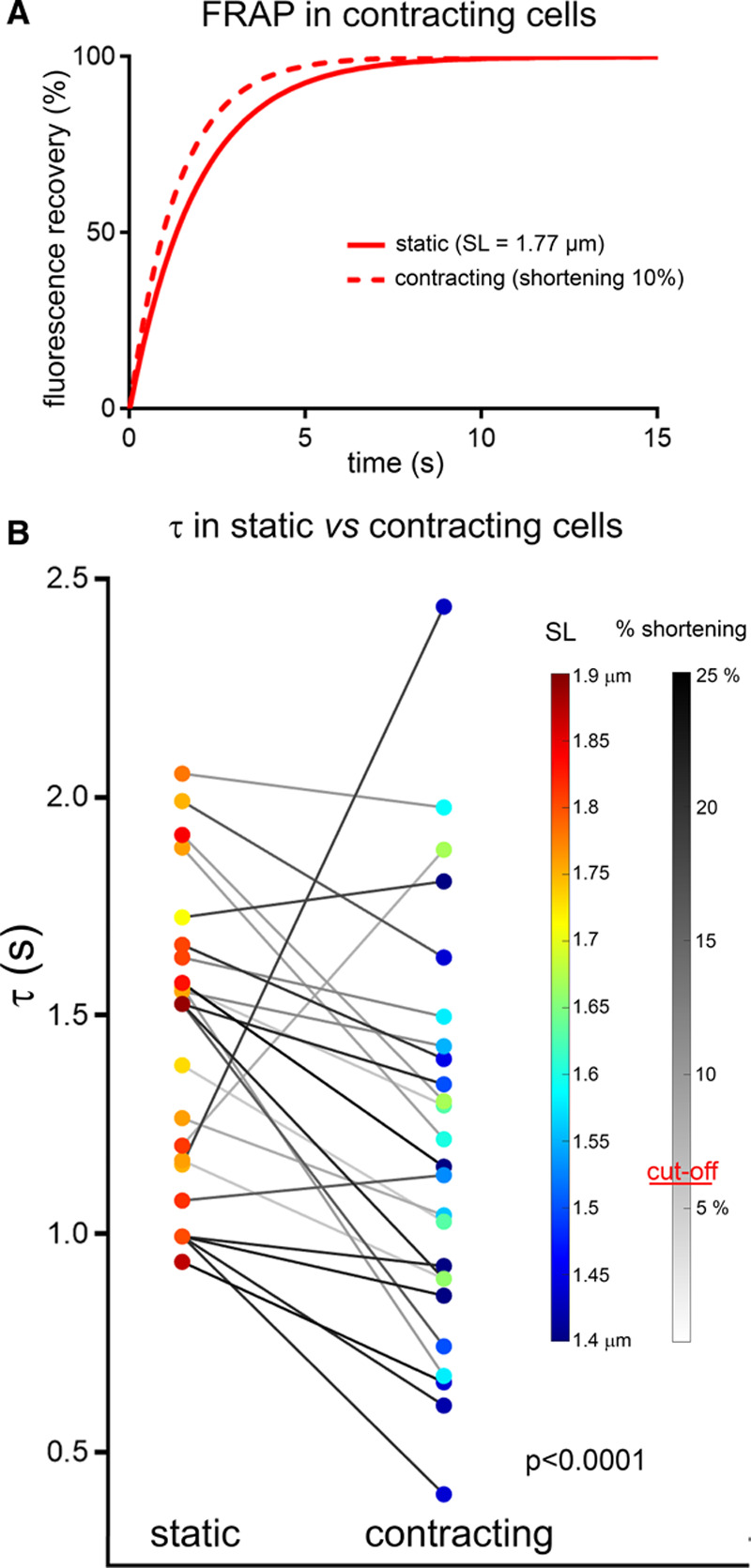

Apparent Speed of TT Diffusion During Dynamic Changes in SL

To assess the impact of cyclic contractile activity of cardiac cells on the speed of particle movement inside the TT network, paired FRAP measurements were performed on cells at rest and during field stimulation (0.5–1.5 Hz), with variable sequence of both conditions. Cells were included in the analysis only if (1) SL at rest was ≥1.7 µm (ie, noncontractured cells), (2) the degree of shortening was ≥6% (ie, cells showing a competent mechanical response to electrical stimulation), and (3) at least one beat occurred during the first 70% of FRAP recovery phase (to obtain meaningful data).

In contrast to static deformation data, where any deviation from resting SL was associated with an increased τ (Figure 3C; see also Online Figure IVA), the apparent speed of diffusion was increased during dynamic contractions, compared with the same cell at rest (Figure 4A and 4B). This was the case in 21 out of 25 cells. For the cohort as a whole, τ was significantly decreased (by 16%) during dynamic contractions.

Figure 4.

Apparent speed of transverse tubule diffusion is increased during dynamic contraction and relaxation (live cells). A, Representative fitted fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) curves, obtained from one and the same cell at rest and during field stimulation-induced contractions (here at 0.8 Hz). B, Fluorescence recovery times (τ) in cells at rest and during rhythmic contractions (0.5–1.5 Hz, paired observations). Both diastolic and end-systolic sarcomere length (SL) are color-coded, and the extent of percentage shortening during contraction is indicated by the gray-level of connecting lines. Data analyzed using paired T-test, random mixed effect model confirmed a lack of significant effects of heart and cell. N=5 hearts/25 cells.

Additional Structural Observations

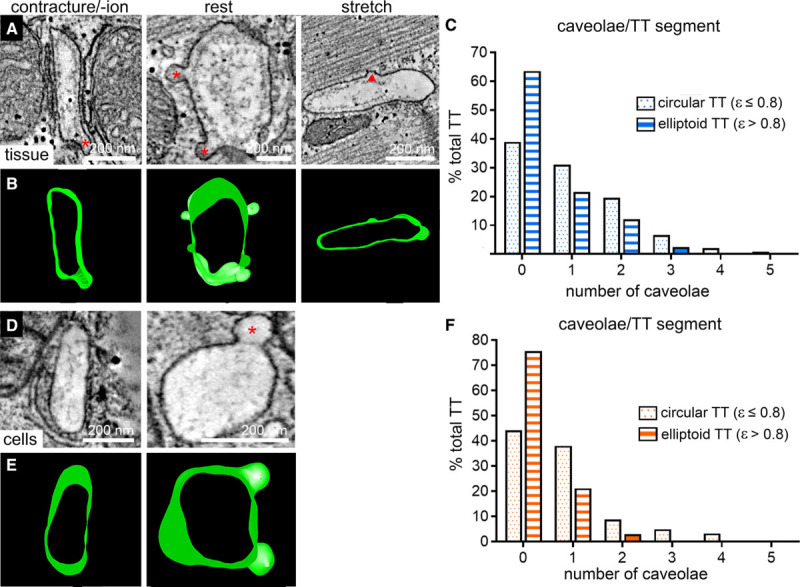

We recently described the regular occurrence of caveolae in TT membranes.47 Here, we assessed their presence during different, SL-dependent TT deformation states. Caveolae (defined as omega-shaped and possessing a neck that is narrower than the main caveolae body; see red asterisks in Figure 5A and 5D) were significantly more frequently observed in TT whose cross-sections have low eccentricity (ε≤0.8 versus >0.8; Figure 5C and 5F; see also Online Figure VI). This is true for both static (tissue, Figure 5A through 5C) and dynamic (isolated cells, Figure 5D through 5F) deformation data. Of note, TT with elevated eccentricity often contained what appeared to be semi-integrated caveolae (see red triangle in Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Presence of caveolae is inversely related to transverse tubule (TT) eccentricity during static (chemically fixed tissue) and dynamic (high-pressure freezing-preserved cells) changes in sarcomere length. A and B, Representative electron tomography (ET) slices and segmented 3-dimensional models demonstrating the presence of TT caveolae in tissue preserved at contracture, rest, or stretch (red stars indicate caveolae; red triangle marks site of presumed partial membrane integration of caveolae). C, Frequency distribution histograms of the number of caveolae observed in TT segments (250 nm length) with cross-sectional eccentricity ε≤0.8 (dotted blue bars, n=241 TT) and ε>0.8 (striped blue bars, n=298 TT) in tissue, N=7 hearts/29 tissue samples/125 cells, see also Online Figure VI and Online Table I. D and E, Representative ET slices and segmented models demonstrating the presence of TT caveolae in cells preserved during contraction or at rest (red star indicates caveolae). F, Frequency distribution histograms of the number of caveolae observed in TT segments (250 nm length) with cross-sectional eccentricity of ε≤0.8 (dotted orange bars, n=181 TT) and ε>0.8 (striped orange bars, n=33 TT) in cells, N=2 hearts/16 tissue samples/56 cells, see also Online Figure VI and Online Table II.

Discussion

We provide structural and functional confirmation of cell contraction-induced, mechanically assisted TT content exchange on a beat-by-beat basis. We propose that the advective TT flux described here may help to stabilize the luminal concentrations of ions relevant for ECC.

Advection-assisted diffusion in TT had originally been proposed in 2003, based on 2-dimensional EM data obtained from isolated rabbit hearts, chemically fixed in 3 static deformation settings (Li+-induced contracture, K+ cardioplegic arrest, balloon inflation).48 The physiological utility of such an advective contribution to TT luminal content exchange arises out of a spatially uneven distributions of trans-sarcolemmal ion flux pathways that are relevant for ECC in TT and cell surface sarcolemma which, combined with restricted diffusion inside TT, may affect TT content homeostasis.

Subsequent work involving experimental and computational models suggested that TT become cyclically flattened during the contraction-relaxation cycle, which—assuming a constant surface area of TT (lipid bilayer rupture strain is ≈2%)49—would be a potential driver for advection of TT content.12,15,38 However, none of the studies to date provided nanoscopic 3D reconstructions at a resolution that would allow individual TT surface and volume assessment, and no observations were made on a time-base suitable for assessing whether or not structural and functional changes are operational on a beat-by-beat basis.

In the present study, we used electron tomography to assess the 3D geometry of individual 250 nm-long TT segments, with single-nanometer isotropic voxel dimensions, during static (minutes) and dynamic (beat-by-beat) cardiomyocyte deformation. Static interventions used the 2003 approach,48 covering an SL range from end-diastolic stretch (≥2.2 μm) to peak contracture (≤1.6 μm), using chemically fixed tissue. Dynamic samples were produced using HPF of electrically paced isolated cells, preserved with millisecond accuracy during different stages of their active contraction and relaxation. The second approach does not allow for stretching of cells, but it circumvents potential chemical-fixation induced structural artifacts, and it eliminates the otherwise nonphysiological delays between the initiation of a mechanical deformation and sample fixation.

Both static and dynamic contractions provided consistent structural results, demonstrating that stretch and contraction lead to an SL-correlated flattening of TT (increasing eccentricity), in mutually perpendicular directions: parallel to the cell’s long axis during stretch; parallel to Z-lines during contraction. Thus, TT eccentricity waxes and wanes twice per cardiac cycle, with maximal eccentricity values during end-diastole and end-systole.

The observed TT deformation may be a consequence of lateral squeezing by neighboring contractile lattice structures (such as recently suggested for cardiac mitochondria) or be conferred through mechanical signals along cytoskeletal elements such as microtubules,50 which have been shown to be closely associated with TT and jSR.51

Increased eccentricity is associated with a reduction in TT volume:surface ratio, supporting our hypothesis of TT luminal volume changes during cell deformation. While evident both in static and dynamic samples, the latter showed a better match to theoretically predicted behavior, perhaps indicating that deformations of cellular components, sustained for minutes, and/or chemical fixation, affect cellular ultrastructure in ways that may not be compatible with physiologically observed and cyclically reversible changes. Additional factors that could contribute to the discrepancy between observed (in chemically fixed tissue) and modeled data are potential differences in TT content (viscosity, presence of collagen fibers)52 in intact tissue versus isolated cells. Possible contributions due to differential swelling, for example, during contracture, were ruled out, based on an assessment of mitochondrial dimensions in our experimental groups (Online Figure VII).

In addition, we observed evidence for integration of TT caveolae into the TT surface membrane at high eccentricity (ie, implicitly at high volume:surface mismatch, compared with the resting state), a process that could potentially involve up to 10% of TT membrane area.47 The predominance of caveolae in low eccentricity TT is evident also in cell-cycle-timed HPF-preserved cells. This suggests that caveolae are in- and ex-corporated into/from the projected TT membrane surface twice on every cardiac cycle, offering up to 9% spare volume accommodation capacity in our data. Aside from a purely mechanical aspect—similar to that observed previously for surface sarcolemmal caveolae that provide spare membrane during mechanical stretch48,53—the potential relevance of this process for mechanical modulation of caveolar signaling hubs warrants further investigation in homeostasis and during remodeling of the TT system, such as in cardiac hypertrophy or failure.

The effect of TT deformation on luminal particle movement, predicted from beat-by-beat 3D nanostructural observations, was functionally tested in live cells by confocal microscopy. Using FRAP, we established the apparent speed of diffusion in TT of cells at rest, during contracture, during passive static stretch, and during cyclic contractions. In static conditions (noncontracting cells), contracture and stretch were both associated with a significant slowing of what one might call steady-state FRAP, compared to resting cells. This may be explained by the fact that at high eccentricities the minor axis of TT may become a limiting factor for diffusion, an effect that would be aggravated by the presence of a 35 to 50 nm basal lamina (glycocalyx) layer all around the inner TT surface, which would limit the TT lumen that allows relatively unhindered diffusion in high eccentricity TT. Additionally, the glycocalyx could trap ions (especially divalent cations, given that glycocalyx is negatively charged), as suggested in previous studies.35 This could affect the kinetics of Ca2+ movement in TT and across the TT sarcolemma, by creating a gradient between near-sarcolemmal Ca2+ concentration and that of the bulk extracellular space.54

In contrast, dynamically contracting cells show faster FRAP, compared with same-cell measurements at resting length. This is compatible with a mechanical deformation-induced advective contribution to local mixing and TT content exchange (according to structural observations, this could affect between one quarter and one-third of TT volume, twice during each cardiac cycle). An advective contribution to TT diffusion would be expected to counter potential TT luminal ion concentration changes (eg, depletion of Ca2+),33–35 for instance at high beating rates, as changes in the number of ECC coupling events (one per beat) would be accompanied by changes in the number of TT eccentricity changes (two per beat).

What makes the observed increase in speed of FRAP in contracting cardiomyocytes (compared with resting cells) even more impressive is the fact that contracting cells cycle between their fastest steady-state FRAP condition at resting length and significantly slower states at high eccentricity TT configurations. Based on our static deformation FRAP data, this should be expected to slow TT luminal diffusion, and it thus demonstrates the potentially high physiological relevance of mechanically assisted diffusion as a mechanism for TT content homeostasis. To illustrate this, if we assumed that, in a beating heart, cells spend about 50% of their time in a stretched state (τ≈4 seconds); 30% near slack (τ≈1.5 seconds), and 20% at peak contraction (τ≈4 seconds), this would translate into an averaged recovery time constant of ≈3.3 seconds in beating cells. We observe, however, τ≈1.2 seconds during contractions, so an almost 3-fold decrease compared with what would be expected based on a simplistic consideration of static data. In the future, it would be very interesting to test how the amplitude of contractions or variable preloads might affect the speed of TT luminal diffusion.

Further relevance of the here described mechanisms may arise when considering the impact of pathological remodeling on the cardiac TT network. TT derangement (eg, altered shape, continuity, volume fraction, spatial relationship of TT and jSR, as well as changes in the proportion of longitudinal and transverse elements) is a hallmark of many cardiovascular diseases.3 These changes have been linked to alterations in Ca2+ handling and contractile function, and they may, in part, be linked to impaired TT lumen homeostasis. Equally interesting would be the elucidation of the here illustrated behavior in atrial cells, which have a more pronounced proportion of longitudinal TT network elements that serve as major hubs for atrial ECC.1 A detailed characterization of mechanically induced deformation of longitudinal TT elements and the effect on luminal content would be interesting also in the light of previously reported differences in particle penetration between transverse and longitudinal TT segments.10

Several limitations of the here presented study ought to be taken into consideration. Although we used relatively small dextran particles (stokes radius ≈2.0 nm) to probe diffusion in TT, they are significantly larger than ions, so diffusional restrictions that affect ECC may emerge later, or be less severe, than seen here. Furthermore, while plausible (based on the evidence for inhomogeneous ion in- and out-flux topologies in TT and surface membranes of cardiac myocytes), ionic gradients along the TT network as a consequence of rhythmic electrical activity in the presence or absence of contractile activity have yet to be characterized in detail. Also, the majority of studies into TT function and luminal content dynamics have been conducted using isolated cells with access to a near infinite supply of surrounding medium. In intact tissue, restrictions because of limited extracellular volume and space between cells may affect the propensity for the formation of ion gradients within TT. Finally, previously described species-dependent differences in TT structure and function have not been a subject of this investigation, so they should be taken into account in follow-up research.6,7 While rabbit TT exhibit a higher degree of structural similarity to human than murine cardiomyocytes, it would be interesting to explore how spatial restrictions, for example, near the TT mouth of mouse cardiomyocytes, may alter diffusion inside the TT network in the species that has been a major source for cardiac electrophysiology and ECC data.55

In summary, we provide structural and functional evidence for the existence of a cell contraction-induced advective contribution to TT luminal content exchange, and we show that this mechanism works on a beat-by-beat basis. Mechanically assisted diffusion, present under physiological conditions, may gain in relevance during increased demand (both in terms of heart rate and stroke volume), potentially aiding autoregulatory upkeep of TT content in a use-dependent manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia Page, Cindi Schwartz, and David Mastronarde (University of Colorado), Martin Schorb and Rachel Mellwig (EMBL Electron Microsopy Core Facility) for help with electron tomography imaging; Roland Nitschke and staff at the Life Imaging Center, in the Center for Biological Systems Analysis (ZBSA) of the Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, for help with confocal microscopy resources; the Super-Resolution Confocal/Multiphoton Imaging for Multiparametric Experimental Designs (SCI-MED) facility at IEKM for image analysis support; Cinthia Walz, Stefanie Perez-Feliz, Ramona Kopton, Ilona Bodi, and Tibor Hornyik for help with cell isolation. We thank Clemens Kreutz (Institute of Medical Biometry and Statistics) for valuable statistical advice. This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation Immediate Fellowship (to E.A. Rog-Zielinska, FS/15/3/31047) and by the European Research Council Advanced Grant CardioNect (to P. Kohl, ERC 323099). E.A. Rog-Zielinska is a DFG Emmy Noether Fellow (DFG 396913060). E.A. Rog-Zielinska, R. Peyronnet, C.M. Zgierski-Johnston, J. Greiner, J. Madl, L. Sacconi, and P. Kohl are members of the German Collaborative Research Centre SFB1425 (DFG 422681845).

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Materials

Online Figures I–IX

Online Tables I–III

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ECC

- excitation-contraction coupling

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- HPF

- high-pressure freezing

- SL

- sarcomere length

- TT

- transverse tubules

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317266.

For Disclosures, see page 214.

Contributor Information

Marina Scardigli, Email: scardigli@lens.unifi.it.

Remi Peyronnet, Email: remi.peyronnet@universitaets-herzzentrum.de.

Callum M. Zgierski-Johnston, Email: callum.michael.johnston@universitaets-herzzentrum.de.

Joachim Greiner, Email: joachim.greiner@universitaets-herzzentrum.de.

Josef Madl, Email: josef.madl@universitaets-herzzentrum.de.

Eileen T. O’Toole, Email: Eileen.Otoole@Colorado.EDU.

Mary Morphew, Email: Mary.Morphew@Colorado.EDU.

Andreas Hoenger, Email: hoenger@colorado.edu.

Leonardo Sacconi, Email: sacconi@lens.unifi.it.

Peter Kohl, Email: peter.kohl@universitaets-herzzentrum.de.

Novelty and Significance

What Is Known?

Cardiac muscle cells contain a complex network of tubular membrane invaginations called T-tubules (TT), extending deep into the cell and containing extracellular fluid.

Cardiac TT are essential for the link between the electrical activity, calcium signaling, and contraction of the heart.

The balance between TT content and bulk extracellular space can change as a result of net ion flow across the TT membrane and restricted diffusion deep inside the TT network.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Cardiac TT are deformed (squeezed) twice during each heart beat—during diastolic loading and during peak contraction.

The shape of the TT affects the speed of diffusion inside the TT network.

Dynamic squeezing leads to pumping of TT content, accelerating the exchange between TT content and bulk extracellular space.

This TT content pumping mechanism may resolve the riddle as to how cardiac cells deal with the challenge of net ion fluxes between TT lumen and cell interior. This mechanism for content maintenance would be use-dependent, scaling up in relevance as demand rises: at higher heart rates, the increased number of ion flux cycles (and, consequently, changes in TT luminal content) would be countered by a twice-as-large rise in the number (and, possibly, the extent) of the here discovered convection-assisted diffusion cycles. The fundamental mechanism we describe may potentially contribute to functional deterioration in heart failure, where TT remodeling and associated electromechanical dysfunction are two closely associated clinical features.

References

- 1.Brandenburg S, Kohl T, Williams GS, Gusev K, Wagner E, Rog-Zielinska EA, Hebisch E, Dura M, Didié M, Gotthardt M, et al. Axial tubule junctions control rapid calcium signaling in atria. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3999–4015. doi: 10.1172/JCI88241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong T, Shaw RM. Cardiac t-tubule microanatomy and function. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:227–252. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orchard C, Brette F. T-tubules and sarcoplasmic reticulum function in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:237–244. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soeller C, Cannell MB. Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ Res. 1999;84:266–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong CHT, Rog-Zielinska EA, Orchard CH, Kohl P, Cannell MB. Sub-microscopic analysis of t-tubule geometry in living cardiac ventricular myocytes using a shape-based analysis method. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;108:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong CHT, Rog-Zielinska EA, Kohl P, Orchard CH, Cannell MB. Solute movement in the t-tubule system of rabbit and mouse cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E7073–E7080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805979115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rog-Zielinska EA, Kong CHT, Zgierski-Johnston CM, Verkade P, Mantell J, Cannell MB, Kohl P. Species differences in the morphology of transverse tubule openings in cardiomyocytes. Europace. 2018;20:iii120–iii124. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida K, Lopatin AN. Diffusional and electrical properties of T-tubules are governed by their constrictions and dilations. Biophys J. 2018;114:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pásek M, Simurda J, Christé G, Orchard CH. Modelling the cardiac transverse-axial tubular system. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:226–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parfenov AS, Salnikov V, Lederer WJ, Lukyánenko V. Aqueous diffusion pathways as a part of the ventricular cell ultrastructure. Biophys J. 2006;90:1107–1119. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blatter LA, Niggli E. Confocal near-membrane detection of calcium in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNary TG, Spitzer KW, Holloway H, Bridge JH, Kohl P, Sachse FB. Mechanical modulation of the transverse tubular system of ventricular cardiomyocytes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2012;110:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepherd N, McDonough HB. Ionic diffusion in transverse tubules of cardiac ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H852–H860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swift F, Strømme TA, Amundsen B, Sejersted OM, Sjaastad I. Slow diffusion of K+ in the T tubules of rat cardiomyocytes. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;101:1170–1176. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00297.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orchard CH, Pásek M, Brette F. The role of mammalian cardiac t-tubules in excitation-contraction coupling: experimental and computational approaches. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:509–519. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scriven DR, Dan P, Moore ED. Distribution of proteins implicated in excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2000;79:2682–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76506-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brette F, Sallé L, Orchard CH. Differential modulation of L-type Ca2+ current by SR Ca2+ release at the T-tubules and surface membrane of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2004;95:e1–e7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000135547.53927.F6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brette F, Sallé L, Orchard CH. Quantification of calcium entry at the T-tubules and surface membrane in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2006;90:381–389. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai M, Hussain M, Orchard CH. Excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes after formamide-induced detubulation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H603–H609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant SM, Kong CH, Watson J, Cannell MB, James AF, Orchard CH. Altered distribution of ICa impairs Ca release at the t-tubules of ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;86:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubasov IV, Stepanov A, Bobkov D, Radwanski PB, Terpilowski MA, Dobretsov M, Gyorke S. Sub-cellular electrical heterogeneity revealed by loose patch recording reflects differential localization of sarcolemmal ion channels in intact rat hearts. Front Physiol. 2018;9:61 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carl SL, Felix K, Caswell AH, Brandt NR, Ball WJ, Jr, Vaghy PL, Meissner G, Ferguson DG. Immunolocalization of sarcolemmal dihydropyridine receptor and sarcoplasmic reticular triadin and ryanodine receptor in rabbit ventricle and atrium. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:673–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kieval RS, Bloch RJ, Lindenmayer GE, Ambesi A, Lederer WJ. Immunofluorescence localization of the Na-Ca exchanger in heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C545–C550. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.2.C545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank JS, Mottino G, Reid D, Molday RS, Philipson KD. Distribution of the Na(+)-Ca2+ exchange protein in mammalian cardiac myocytes: an immunofluorescence and immunocolloidal gold-labeling study. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:337–345. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.2.337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald RL, Colyer J, Harrison SM. Quantitative analysis of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger expression in guinea-pig heart. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5142–5148. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Despa S, Brette F, Orchard CH, Bers DM. Na/Ca exchange and Na/K-ATPase function are equally concentrated in transverse tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2003;85:3388–3396. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74758-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas MJ, Sjaastad I, Andersen K, Helm PJ, Wasserstrom JA, Sejersted OM, Ottersen OP. Localization and function of the Na+/Ca2+-exchanger in normal and detubulated rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1325–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z, Pascarel C, Steele DS, Komukai K, Brette F, Orchard CH. Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity is localized in the T-tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:315–322. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000030180.06028.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chase A, Orchard CH. Ca efflux via the sarcolemmal Ca ATPase occurs only in the t-tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadeberg HC, Bryant SM, James AF, Orchard CH. Altered Na/Ca exchange distribution in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H262–H268. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00597.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisner DA. Ups and downs of calcium in the heart. J Physiol. 2018;596:19–30. doi: 10.1113/JP275130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shattock MJ, Bers DM. Rat vs. rabbit ventricle: Ca flux and intracellular Na assessed by ion-selective microelectrodes. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:C813–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.4.C813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bers DM. Early transient depletion of extracellular Ca during individual cardiac muscle contractions. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:H462–H468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.3.H462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bers DM, Peskoff A. Diffusion around a cardiac calcium channel and the role of surface bound calcium. Biophys J. 1991;59:703–721. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almers W, Fink R, Palade PT. Calcium depletion in frog muscle tubules: the decline of calcium current under maintained depolarization. J Physiol. 1981;312:177–207. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barry PH, Adrian RH. Slow conductance changes due to potassium depletion in the transverse tubules of frog muscle fibers during hyperpolarizing pulses. J Membr Biol. 1973;14:243–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01868081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savio-Galimberti E, Frank J, Inoue M, Goldhaber JI, Cannell MB, Bridge JH, Sachse FB. Novel features of the rabbit transverse tubular system revealed by quantitative analysis of three-dimensional reconstructions from confocal images. Biophys J. 2008;95:2053–2062. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacconi L, Ferrantini C, Lotti J, Coppini R, Yan P, Loew LM, Tesi C, Cerbai E, Poggesi C, Pavone FS. Action potential propagation in transverse-axial tubular system is impaired in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5815–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120188109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pásek M, Simurda J, Orchard CH, Christé G. A model of the guinea-pig ventricular cardiac myocyte incorporating a transverse-axial tubular system. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:258–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNary TG, Bridge JH, Sachse FB. Strain transfer in ventricular cardiomyocytes to their transverse tubular system revealed by scanning confocal microscopy. Biophys J. 2011;100:L53–L55. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rog-Zielinska EA, Johnston CM, O’Toole ET, Morphew M, Hoenger A, Kohl P. Electron tomography of rabbit cardiomyocyte three-dimensional ultrastructure. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016;121:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopton RA, Baillie JS, Rafferty SA, Moss R, Zgierski-Johnston CM, Prykhozhij SV, Stoyek MR, Smith FM, Kohl P, Quinn TA, et al. Cardiac electrophysiological effects of light-activated chloride channels. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1806 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scardigli M, Crocini C, Ferrantini C, Gabbrielli T, Silvestri L, Coppini R, Tesi C, Rog-Zielinska EA, Kohl P, Cerbai E, et al. Quantitative assessment of passive electrical properties of the cardiac T-tubular system by FRAP microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:5737–5742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702188114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peyronnet R, Bollensdorff C, Capel RA, Rog-Zielinska EA, Woods CE, Charo DN, Lookin O, Fajardo G, Ho M, Quertermous T, et al. Load-dependent effects of apelin on murine cardiomyocytes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2017;130:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burton RAB, Rog-Zielinska EA, Corbett AD, Peyronnet R, Bodi I, Fink M, Sheldon J, Hoenger A, Calaghan SC, Bub G, et al. Caveolae in rabbit ventricular myocytes: distribution and dynamic diminution after cell isolation. Biophys J. 2017;113:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohl P, Cooper PJ, Holloway H. Effects of acute ventricular volume manipulation on in situ cardiomyocyte cell membrane configuration. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00024-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morris CE, Homann U. Cell surface area regulation and membrane tension. J Membr Biol. 2001;179:79–102. doi: 10.1007/s002320010040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rog-Zielinska EA, O’Toole ET, Hoenger A, Kohl P. Mitochondrial deformation during the cardiac mechanical cycle. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2019;302:146–152. doi: 10.1002/ar.23917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iribe G, Ward CW, Camelliti P, Bollensdorff C, Mason F, Burton RA, Garny A, Morphew MK, Hoenger A, Lederer WJ, et al. Axial stretch of rat single ventricular cardiomyocytes causes an acute and transient increase in Ca2+ spark rate. Circ Res. 2009;104:787–795. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.193334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crossman DJ, Shen X, Jüllig M, Munro M, Hou Y, Middleditch M, Shrestha D, Li A, Lal S, Dos Remedios CG, et al. Increased collagen within the transverse tubules in human heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:879–891. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfeiffer ER, Wright AT, Edwards AG, Stowe JC, McNall K, Tan J, Niesman I, Patel HH, Roth DM, Omens JH, et al. Caveolae in ventricular myocytes are required for stretch-dependent conduction slowing. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;76:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao A, Spitzer KW, Ito N, Zaniboni M, Lorell BH, Barry WH. The restriction of diffusion of cations at the external surface of cardiac myocytes varies between species. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:431–438. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hong T, Yang H, Zhang SS, Cho HC, Kalashnikova M, Sun B, Zhang H, Bhargava A, Grabe M, Olgin J, et al. Cardiac BIN1 folds T-tubule membrane, controlling ion flux and limiting arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2014;20:624–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.