Abstract

目的

探讨EB病毒(EBV)阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体对淋巴管新生与鼻咽癌淋巴结转移的影响。

方法

利用超速离心获得细胞外泌体,对外泌体进行Western blot与纳米颗粒追踪分析(NTA)鉴定。利用Dio染料吞噬实验,验证外泌体可以被淋巴管内皮细胞摄取。离体条件下,分别利用等体积培养基以及20 μg/mL鼻咽上皮细胞(NP69)、HK1-EBV、C666-1细胞外泌体和除去外泌体的HK1-EBV与C666-1上清蛋白预处理淋巴管内皮细胞,检测淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移情况;在体实验,首先建立裸鼠腘窝淋巴结转移模型,负瘤裸鼠被随机分成4组,3只/组。对照组:腘窝处注射生理盐水(30 μL);NP69外泌体组:10 μg/30 μL NP69外泌体;HK1-EBV除去外泌体上清组:10 μg/30 μL HK1-EBV除去外泌体上清蛋白;HK1-EBV外泌体组:10 μg/30 μL HK1-EBV外泌体。每2 d注射1次,共4次。

结果

超速离心获得外泌体富含外泌体特异性蛋白,同时NTA鉴定表明其粒径范围正常;鼻咽癌细胞与NP69外泌体可以被淋巴管内皮细胞摄取;HK1-EBV与C666-1外泌体较空白对照组与NP69外泌体可显著促进淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移(P < 0.05),HK1-EBV与C666-1外泌体组与对应除去外泌体上清蛋白组间无显著性差异(P > 0.05);腘窝淋巴结转移实验发现:HK1-EBV外泌体较空白对照组、NP69外泌体以及除去外泌体的HK1-EBV上清蛋白可显著促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移以及局部淋巴管新生(P < 0.05)。

结论

EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体能促进鼻咽癌淋巴管新生与淋巴结转移。

Keywords: EB病毒, 鼻咽癌, 外泌体, 淋巴结转移, 肿瘤微环境, 淋巴管新生

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effect of exosomes derived from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells on lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis of NPC.

Methods

Exosomes from NP69 cells and EBV-positive HK1 (HK1-EBV) cells were obtained by ultracentrifugation and identified by Western blotting and nanoparticle tracking analysis. Dio dye phagocytosis test was performed to observe exosome uptake by lymphatic endothelial cells. Lymphatic endothelial cells were treated with exosomes from nasopharyngeal epithelium (NP69), HK1-EBV, and C666-1 cells or exosome-free supernatant of HK1-EBV and C666-1 cells, and tube formation and migration of the cells were observed. In a nude mouse model of popliteal lymph node metastasis of NPC, the effects of normal saline, NP69 cell-derived exosomes, HK1-EBV cell-derived exosomes, exosome-free supernatant of HK1-EBV cells, and HK1-EBV exosome-free supernatant protein on lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis of the tumor were observed.

Results

The exosomes obtained by ultracentrifugation contained abundant exosome-specific proteins and showed a normal size range. The exosomes from NPC cells and NP69 cells could be taken up by lymphatic endothelial cells. Compared with the blank control and exosomes form NP69 cells, exosomes derived from HK1-EBV and C666-1 cells significantly promoted tube formation and migration of lymphatic endothelial cells (P < 0.05), and the exosomes and exosome-free supernatant of HK1-EBV and C666-1 cell produced similar effects (P > 0.05). In the tumor-bearing nude mice, exosomes derived from HK1-EBV cells significantly promoted metastasis of NPC cells and local lymphangiogenesis compared with the blank control, NP69 cell-derived exosomes and exosome-free supernatant of HK1-EBV cells (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Exosomes from EBV-positive NPC cells can significantly promote lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis of NPC.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, exosome, lymph node metastasis, tumor microenvironment, lymphangiogenesis

鼻咽癌是中国南方与东南亚地区常见恶性肿瘤之一,且与EB病毒(EBV)感染密切相关,每年大约有80 000名新诊断病例,是世界第3高发的病毒诱导的肿瘤[1]。世卫组织依据角质化与分化程度将鼻咽癌分成三类:角质化鳞状上皮肿瘤、分化型非角质化肿瘤与未分化型非角质化肿瘤,其中未分化型非角质化肿瘤最为常见且与EBV密切相关,该类型鼻咽癌更易发生转移[2]。淋巴结转移在鼻咽癌病人中极为常见,淋巴结转移可侵犯临近血管与神经,增加治疗难度。同时发现淋巴结转移患者更容易发生远端转移,从而导致治疗失败。研究表明鼻咽癌患者血液中EBV-DNA含量与颈部淋巴结转移的体积呈正相关[3],且EBV与鼻咽癌淋巴结转移密切关联[4]。我们课题组前期工作证实EBV的miRNA通过抑制鼻咽癌细胞内PTEN表达,增加鼻咽癌细胞自身生长、存活与侵袭从而促进鼻咽癌远端转移[5-6]。然而,目前EBV在鼻咽癌淋巴结转移中的作用以及机制还不清楚,因此探讨EBV促进鼻咽癌淋巴管新生机制,针对这些机制特异性地靶向对抗淋巴管新生,对于抑制鼻咽癌的转移与复发、改善鼻咽癌患者的预后、提高生存率具有重要意义。

目前越来越多的研究表明外泌体参与肿瘤的生长、血管新生、转移、耐药以及免疫调节等过程。早在2011年研究者就发现黑色素瘤细胞释放的外泌体促进前哨淋巴结内血管新生、基质沉淀与淋巴细胞免疫反应,进而有利于肿瘤转移[7]。近期研究发现宫颈癌细胞产生富含miR-221-3p的外泌体促进淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移[8]。EBV产生的LMP1蛋白可以通过被感染细胞产生外泌体传递到单核细胞与T淋巴细胞,抑制上述细胞增殖[9],从而促进上皮细胞与B淋巴细胞增殖[10-11]。在EBV阳性的鼻咽癌细胞产生的外泌体中,galectin-9可以抑制Th1淋巴细胞免疫反应[12],LMP-1调控的HIF-1α可以通过外泌体传递到低表达HIF-1α的鼻咽癌细胞,促进低表达鼻咽癌细胞迁移[13]。由此可见,EBV感染细胞产生外泌体携带病毒或者细胞成分可改变肿瘤微环境,使其有利于肿瘤的发生与发展。上述针对EBV阳性鼻咽癌外泌体的研究主要集中在免疫调节与晚期转移,但EBV阳性鼻咽癌外泌体是否参与鼻咽癌早期转移如淋巴结转移还未知。同时前期研究发现鼻咽癌病人血液中EBV DNA含量与淋巴结转移的指标成正相关[14-15],结果提示EBV可能参与鼻咽癌淋巴结转移。因此,我们有理由推测EBV感染鼻咽癌细胞外泌体可能参与淋巴管新生以及鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 材料

细胞培养基RPMI 1640、胰酶(Gibco,USA),胎牛血清(BI,UT,USA),抗体VDAC1(ab15895,1:1000稀释)、Calreticulin(ab92516,1:1000稀释)、Calnexin(ab92573,1:1000稀释)、Syntenin(ab133267,1:1000稀释)、Flotillin-1(ab41927,1:1000稀释)、CD63(ab217345,1:1000稀释)与LYVE1(ab4917,1:200稀释)(abcam),染料分子Dio(D4292)(sigma),matrigel(Corning 354230),Transwell小室(Corning,24918040),超速离心机(XPN- 100),纳米追踪分析仪(马尔文3000),小动物活体成像仪(IVIS Lumina II),共聚焦显微镜(NT-88NE-N2),EBV阳性人鼻咽癌细胞系C666-1、HK1-EBV,永生化人鼻咽粘膜上皮细胞NP69均获赠于香港大学,人淋巴管内皮细胞(HLECs)购自scicell公司,BALB/c裸鼠(北京维通利华实验动物技术有限公司)。

1.2. 细胞培养基上清外泌体提取与鉴定以及上清蛋白纯化

1.2.1. 外泌体提取

细胞培养基上清外泌体提取:外泌体提取过程参照先前报道步骤[16],在进行传代培养时,收集培养基上清至无菌玻璃瓶内,4 ℃保存以备用,分步离心以获取培养基上清外泌体。(注:含血清培养在细胞培养前要对血清进行120 000 g,过夜超离,除去血清外泌体;如果收集特异性降低某些蛋白的外泌体,培养基收集应该在转染48 h后开始,以充分降低外泌体内蛋白含量)。

1.2.2. Exosome-free上清蛋白制备

参考先前报道方法[17],简述如下:经过超速离心除去外泌体的培养基上清转移至截流孔径为3000的超滤管内,以4500 g的离心力进行超滤浓缩。浓缩至3 mL后,转移到10 mL离心管内,加入7 mL丙酮以及1 g的TCA(终浓度为10%),混匀放置于-20 ℃沉淀2~3 h。20 000 g,30 min(4 ℃),弃上清。向沉淀中加入4倍体积的预冷丙酮,-20 ℃沉淀过夜。4 ℃条件下20 000 g离心30 min,弃上清,沉淀即为Exosome-free蛋白。

1.2.3. Western blot

向超离获得外泌体沉淀加入适当RIPA裂解液和蛋白酶抑制剂并提取蛋白。用BCA法检测蛋白浓度。取4 µg蛋白用聚丙烯酰胺凝胶进行电泳,并转膜至NC膜,分别用Syntenin-1、Flotillin-1、CD63、Calreticulin与Calnexin一抗进行孵育过夜(4 ℃)。用连接过氧化物酶的二抗孵育,最后通过ECL法显影,并放入Bio-Rad高灵敏度化学发光成像系统下曝光成像并拍照。

1.2.4. NTA检测

超速离心获得细胞与血清外泌体,利用经过超离1 mL PBS重悬。为了减少外源颗粒物污染,最好用RNAase-free的枪头与EP管。利用马尔文公司的纳米颗粒分析仪进行颗粒粒度检测。

1.3. 细胞外泌体对淋巴管内皮细胞作用的体外与体内功能实验

1.3.1. 淋巴管内皮细胞管腔成形实验

利用60 µL Materigel预先铺96孔板,37 ℃培养箱静止30 min。消化淋巴管内皮细胞成单个细胞,利用ECM培养基重悬的永生化鼻咽上皮细胞(NP69)、EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞(HK1-EBV与C666-1)外泌体以及除去EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体的培养基上清蛋白,使其终浓度为20 µg/mL。利用上述培养基重悬淋巴管内皮细胞,使其密度为1.5× 105/mL,把100 µL上述细胞悬液加入至96孔板内,同时设置ECM培养基重悬细胞为空白对照。6 h后观察各组淋巴管内皮细胞成管情况,拍照记录。

1.3.2. 淋巴管内皮细胞迁移实验

利用ECM培养基重悬永生化鼻咽上皮细胞(NP69)、EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞(HK1-EBV与C666-1)外泌体以及除去EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体的培养基上清蛋白,使其终浓度为20 µg/mL。分别取100 µL上述培养基,重悬5×104个淋巴管内皮细胞,加入微孔直径为8 µm的Transwell小室上内,同时设置ECM培养基重悬细胞为空白对照。把小室放置于加有600 µL ECM完全培养基(10% FBS+90ECM)的24孔板内。36 h后,甲醛固定30 min,结晶紫染色20 min,用棉签去除上层小室内细胞,PBS洗涤,5 min/次,2次,显微镜下观察。

1.3.3. 在体条件下EBV阳性细胞外泌体对肿瘤淋巴结转移影响

(1)、利用慢病毒(pLent-EF1a-luciferaseCMV-GFP-P2A-Puro)构建稳转鼻咽癌细胞株:首先利用96孔板摸索病毒合适的滴度。确定滴度后,12孔板预先铺板,细胞密度为60%融合度,换掉旧培养基,加入混有病毒的新鲜培养基,48 h后去除培养基。细胞传代至少3次,以确保获得稳定转染的细胞。取2×106细胞于流式细胞仪内进行GFP分选,把分选后的细胞至于6 mm皿内培养,扩大培养同时观察荧光强度变化,直到获得Luciferase稳定表达细胞。

(2)、裸鼠腘窝淋巴结转移模型建立:将离心消化后的重悬于30 µL PBS的1×106个鼻咽癌细胞接种于6周大的Balb/c裸鼠足垫。当裸鼠足垫肿瘤长至约50 mm3时,裸鼠被随机分成4组,3只/组。分别对NP69外泌体组、HK1-EBV除去外泌体上清组和HK1-EBV外泌体组足垫原位注射10 µg NP69细胞外泌体与除去HK1-EBV细胞外泌体后培养基上清蛋白和HK1-EBV细胞外泌体,以及等体积的生理盐水,每2 d注射1次,共4次。当足垫处肿瘤体积为150 mm3,先进行Luciferase成像,然后将小鼠断颈处死,剪开表皮将肿瘤组织与腘窝淋巴结取出。该部分动物实验得到南方医科大学实验动物中心伦理委员会批准通过,伦理批号为:L2018257。

(3)、肿瘤组织DAB染色:用4%多聚甲醛(PFA)固定肿瘤组织4 ℃过夜,利用50%、75%、80%、95%与100%酒精梯度脱水各1 h,二甲苯透明2次,15 min/次,浸蜡包埋,切片,厚度为3 µm,烤片56~60度2 h;60 ℃烘烤20 min,二甲苯浸泡20 min,100%酒精5 min,90%酒精5 min,80%酒精5 min,70%酒精5 min,蒸馏水5 min;微波修复:将玻片加入枸橼酸钠缓冲液的烧杯内,微波加热 < 中高火7 min,停2 min,再高温2 min,慢慢冷却。切片放入湿盒,滴加3% H2O2,常温孵10 min,PBS洗3次,5 min/次;用5%羊血清,37 ℃,封闭30 min;加入LYVE1一抗(PBS+0.5% triton配),4 ℃孵过夜;第2天取出,PBS洗3次,5 min/次。加入对应二抗,室温孵育2 h。PBS洗3次,5 min/次;切片上滴加DAB显色液,镜下控制显色时间,1~10 min,流水终止反应;苏木素复染,约5~10 min,盐酸酒精分化约数秒(可以不用),用自来水缓慢冲约20 min,蓝化;脱水10~20 min,二甲苯透明10 min;中性树胶封片,烤片至黏稠;显微镜下观察,拍照。

1.4. 数据统计分析

使用SPSS-18软件进行统计学分析。实验结果以均数±标准差表示,所有实验至少重复3次。两样本方差分析采用t检验,不同时间点的组间差异运用单因素方差分析进行比较。P < 0.05表示差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 外泌体纯度与粒径鉴定

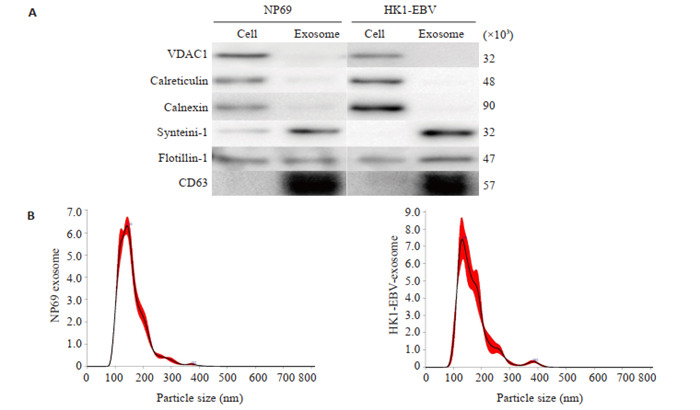

利用免疫印记的方法检测了NP69细胞与HK1-EBV细胞外泌体常见蛋白Syntenin-1、Flotillin-1与CD63以及非外泌体蛋白VDAC1(线粒体),Calreticulin与Calnexin(高尔基体),实验结果显示细胞上清外泌体中Syntenin-1、Flotillin-1与CD63高度富集,VDAC1、Calreticulin与Calnexin含量较少(图 1A)。随后利用NTA分析,发现细胞上清外泌体的粒径范围均集中在30~200 nm之间(图 1B)。

1.

蛋白免疫印记与纳米追踪分析鉴定细胞来源外泌体

Western blotting and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for identification of the cell-derived exo-somes. A: Western blotting for detecting common exosome markers in exosomes from NP69 cells and HK1-EBV cells: syntenin-1, flotillin-1, CD63, calnexin and calreticulin for endoplasmic reticulum, and VDAC1 for mitochondria. B: NTA of size distribution of the exosomes from NP69 cells and HK1-EBV cells.

2.2. 淋巴管内皮细胞可以摄取外泌体

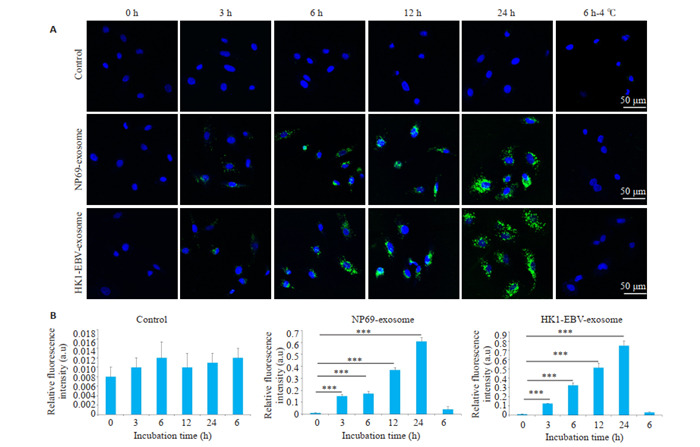

通过细胞外泌体与淋巴管内皮细胞共培养,发现NP69与HK1-EBV细胞外泌体均可以被淋巴管内皮细胞摄取,这种荧光强度随共培养时间延长而增加(图 2A、B),当细胞与外泌体在4 ℃条件下共培养时,细胞摄取外泌体能力显著下降(图 2A、B)。

2.

细胞来源外泌体可以被淋巴管内皮细胞摄取(4 ℃)

Fluorescence patterns showing uptake of cell-derived exosomes by human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLECs). A: Exo-somes from NP69 and HK1-EBV cells are internalized by HLECs, and this process is affected by temperature. B: Quantification of time- and temperature-related relative fluorescence intensity in different groups. ***P < 0.001.

2.3. EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移

利用NP69、C666- 1外泌体以及除去外泌体的C666-1培养基上清、HK1-EBV外泌体以及除去外泌体的HK1-EBV上清分别处理人淋巴管内皮细胞,实验发现EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体较NP69外泌体可以显著促进人淋巴管内皮迁移与成管(P < 0.05,图 3A、B)。同时我们发现除去外泌体的EBV鼻咽癌细胞上清也可以显著促进人淋巴管内皮迁移与成管(P < 0.05,图 3C、D)。

3.

EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移

EBV-positive NPC cell-derived exosomes promote tube formation and migration of lymphatic endothelial cells. A (×100), B: Representative images (left panels) and quantification (right panels) of the Matrigel tube formation assay. C(× 100), D: Representative images (left panels) and quantification (right panels) of the migration assay. *P < 0.05.

2.4. EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移

利用小动物活体成像检测不同组之间腘窝淋巴结转移情况,研究发现HK1-EBV外泌体可以促进鼻咽癌细胞转移到腘窝处(图 4A)。取出腘窝淋巴结,发现HK1-EBV细胞外泌体组腘窝淋巴结体积较NP69细胞外泌体组和空白对照组腘窝淋巴结体积显著增大(P < 0.05),除去外泌体的HK1-EBV上清与NP69细胞外泌体组和空白对照组无显著性差异(P>0.05,图 4B、4C)。

4.

HK1-EBV外泌体促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移

Exosomes from HK1-EBV cells promote lymph node metastasis of NPC. A: Photograph of a nude mouse with popliteal lymph node metastasis. B: Enucleated lymph nodes in different groups. C: Quantification of lymph node volume. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

2.5. EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进足垫处淋巴管密度

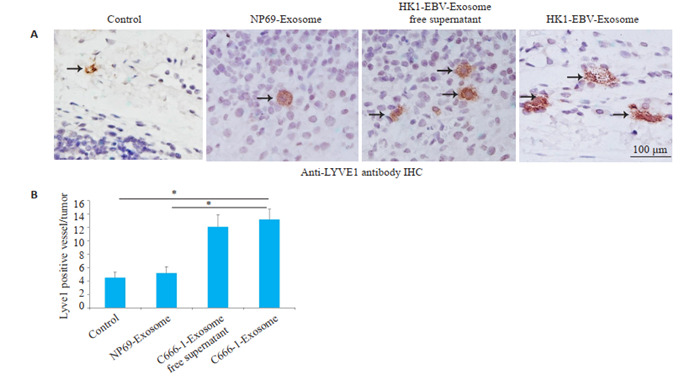

利用LYVE1免疫组化染色对原位肿瘤组织中淋巴管内皮细胞进行标记,结果显示与NP69细胞外泌体和空白对照相比,EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体与除去外泌体EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞上清均可以显著促进淋巴管密度(P < 0.05,图 5A、B)。

5.

HK1-EBV外泌体促进原位肿瘤组织淋巴管新生

HK1-EBV cell-derived exosomes promote lymphangiogenesis in footpad tumors. A: Representative images of microlymphatic vessels stained with anti-LYVE1. B: Quantification of microlymphatic vessel density. *P < 0.05.

3. 讨论

3.1. EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进淋巴结转移

85%鼻咽癌初诊病人伴随淋巴结转移[18-19],发生淋巴结转移不利于鼻咽癌患者的治疗与预后[20],所以控制鼻咽癌淋巴结转移对提高病人预后与生活质量有着重要意义,然而目前对鼻咽以上癌淋巴结转移发生的相关机制还不清楚。几乎所有的鼻咽癌细胞都带有鼻咽癌EBV,EBV是否发挥促进鼻咽癌淋巴结转移的作用还不明确。本研究以外泌体作为切入点,研究EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体对淋巴管内皮细胞的作用,首次发现EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体可以较正常鼻咽上皮细胞显著促进淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移,也可以促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移。这些结果提示EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体可以传递促进淋巴管新生的物质到淋巴管内皮细胞从而促进淋巴管内皮细胞成管与迁移。现在已知外泌体发挥生物效应的物质主要包括蛋白、miRNA和lncRNA等[21-23],具体哪类分子发挥促进淋巴内皮成管与迁移以及鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移,该部分工作需要深入研究。

3.2. 去除外泌体的EBV阳性细胞培养基上清也促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移

众所周知,除了外泌体,细胞外分泌成分还包括分泌性蛋白,分泌性蛋白是否发挥促进鼻咽癌细胞淋巴结转移的作用还未知。本研究发现除去外泌体的培养基上清仍旧可以促进淋巴管内皮细胞迁移、成管以及肿瘤淋巴管新生,说明上清内有促进淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移的蛋白成分,比如已知的一种特异性促进淋巴管新生的外分泌蛋白VEGFC[24-26],其在食管癌、膀胱癌与乳腺癌淋巴结转移中的作用已经得到比较深入的研究[27-30]。EBV能否调控鼻咽癌细胞产生VEGFC从而刺激淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移需要进一步研究。

3.3. 不足点与进一步深入研究地方

本研究发现了EBV阳性鼻咽癌细胞外泌体促进淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移的现象,需要进一步对外泌体内的核酸或者蛋白进行分析,然后寻找促进淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移的效应分子,再进行深入的分子机制探索。另外,患者血清外泌体与正常血清外泌体对淋巴管新生与肿瘤淋巴结转移的作用需要进行验证。

Biography

陈星睿,硕士,E-mail: xingrui0426@126.com

Funding Statement

广州市基础与应用基础研究项目(202002030086)

Contributor Information

陈 星睿 (Xingrui CHEN), Email: xingrui0426@126.com.

钟 水生 (Shuisheng ZHONG), Email: Zhongss999@163.com.

蔡 林波 (Linbo CAI), Email: cailinbo999@163.com.

References

- 1.Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765–77. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2006, 15(10): 1765-77.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi Y, Wakisaka N, Kondo S, et al. Progression of understanding for the role of Epstein-Barr virus and management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36(3):435–47. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9693-x. [Nakanishi Y, Wakisaka N, Kondo S, et al. Progression of understanding for the role of Epstein-Barr virus and management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2017, 36(3): 435-47.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu CL, Chang KP, Lin CY, et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA concentration and clearance rate as novel prognostic factors for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34(8):1064–70. doi: 10.1002/hed.21890. [Hsu CL, Chang KP, Lin CY, et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA concentration and clearance rate as novel prognostic factors for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Head Neck, 2012, 34(8): 1064-70.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao CX, Zhu W, Ba ZQ, et al. The regulatory network of nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis with a focus on EBV, lncRNAs and miRNAs. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8(11):2185–209. [Zhao CX, Zhu W, Ba ZQ, et al. The regulatory network of nasopharyngeal carcinoma metastasis with a focus on EBV, lncRNAs and miRNAs[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2018, 8(11): 2185-209.] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai LM, Lyu XM, Luo WR, et al. EBV-miR-BART7-3p promotes the EMT and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by suppressing the tumor suppressor PTEN. Oncogene. 2015;34(17):2156–66. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.341. [Cai LM, Lyu XM, Luo WR, et al. EBV-miR-BART7-3p promotes the EMT and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by suppressing the tumor suppressor PTEN[J]. Oncogene, 2015, 34 (17): 2156-66.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai LM, Ye YF, Jiang Q, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA BART1 induces tumour metastasis by regulating PTEN-dependent pathways in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7353. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8353. [Cai LM, Ye YF, Jiang Q, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA BART1 induces tumour metastasis by regulating PTEN-dependent pathways in nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Nat Commun, 2015, 6: 7353.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(11):3792–801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4455. [Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor metastasis[J]. Cancer Res, 2011, 71(11): 3792-801.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou CF, Ma J, Huang L, et al. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma-secreted exosomal miR-221-3p promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis by targeting VASH1. Oncogene. 2019;38(8):1256–68. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0511-x. [Zhou CF, Ma J, Huang L, et al. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma-secreted exosomal miR-221-3p promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis by targeting VASH1[J]. Oncogene, 2019, 38 (8): 1256-68.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan J, Middeldorp J, Sculley T. Localization of the Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP1 to exosomes. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(Pt 7):1871–9. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18944-0. [Flanagan J, Middeldorp J, Sculley T. Localization of the Epstein-Barr virus protein LMP1 to exosomes[J]. J Gen Virol, 2003, 84(Pt 7): 1871-9.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanbo A, Kawanishi E, Yoshida R, et al. Exosomes derived from Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells are internalized via caveola-dependent endocytosis and promote phenotypic modulation in target cells. J Virol. 2013;87(18):10334–47. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01310-13. [Nanbo A, Kawanishi E, Yoshida R, et al. Exosomes derived from Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells are internalized via caveola-dependent endocytosis and promote phenotypic modulation in target cells[J]. J Virol, 2013, 87(18): 10334-47.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutzeit C, Nagy N, Gentile M, et al. Exosomes derived from Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines induce proliferation, differentiation, and class-switch recombination in B cells. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):5852–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302068. [Gutzeit C, Nagy N, Gentile M, et al. Exosomes derived from Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines induce proliferation, differentiation, and class-switch recombination in B cells[J]. J Immunol, 2014, 192(12): 5852-62.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klibi J, Niki T, Riedel A, et al. Blood diffusion and Th1-suppressive effects of galectin-9-containing exosomes released by Epstein-Barr virus-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Blood. 2009;113(9):1957–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142596. [Klibi J, Niki T, Riedel A, et al. Blood diffusion and Th1-suppressive effects of galectin-9-containing exosomes released by Epstein-Barr virus-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells[J]. Blood, 2009, 113 (9): 1957-66.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aga M, Bentz GL, Raffa S, et al. Exosomal HIF1α supports invasive potential of nasopharyngeal carcinoma-associated LMP1-positive exosomes. Oncogene. 2014;33(37):4613–22. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.66. [Aga M, Bentz GL, Raffa S, et al. Exosomal HIF1α supports invasive potential of nasopharyngeal carcinoma-associated LMP1-positive exosomes[J]. Oncogene, 2014, 33(37): 4613-22.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo R, Wu H, Wang J, et al. Lymph node status and outcomes for nasopharyngeal carcinoma according to histological subtypes: a SEER population-based retrospective analysis. Adv Ther. 2019;36(11):3123–33. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01100-7. [Guo R, Wu H, Wang J, et al. Lymph node status and outcomes for nasopharyngeal carcinoma according to histological subtypes: a SEER population-based retrospective analysis[J]. Adv Ther, 2019, 36(11): 3123-33.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma BB, King A, Lo YM, et al. Relationship between pretreatment level of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA, tumor burden, and metabolic activity in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(3):714–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.064. [Ma BB, King A, Lo YM, et al. Relationship between pretreatment level of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA, tumor burden, and metabolic activity in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2006, 66(3): 714-20.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li DK, Tian Y, Hu Y, et al. Glioma-associated human endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles specifically promote the tumourigenicity of glioma stem cells via CD9. Oncogene. 2019;38(43):6898–912. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0903-6. [Li DK, Tian Y, Hu Y, et al. Glioma-associated human endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles specifically promote the tumourigenicity of glioma stem cells via CD9[J]. Oncogene, 2019, 38(43): 6898-912.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu YH, Chen XW, Pan QF, et al. A comprehensive proteomics analysis reveals a secretory path- and status-dependent signature of exosomes released from tumor-associated macrophages. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(10):4319–31. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00770. [Zhu YH, Chen XW, Pan QF, et al. A comprehensive proteomics analysis reveals a secretory path- and status-dependent signature of exosomes released from tumor-associated macrophages[J]. J Proteome Res, 2015, 14(10): 4319-31.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang XS, Hu CS, Ying HM, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis from nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on the 2013 updated consensus guidelines for neck node levels. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115(1):41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.02.017. [Wang XS, Hu CS, Ying HM, et al. Patterns of lymph node metastasis from nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on the 2013 updated consensus guidelines for neck node levels[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2015, 115(1): 41-5.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vokes EE, Liebowitz DN, Weichselbaum RR. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 1997;350(9084):1087–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07269-3. [Vokes EE, Liebowitz DN, Weichselbaum RR. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 1997, 350 (9084):1087-91.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee VH, Lam KO, Chang AT, et al. Management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: is adjuvant therapy needed? J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(10):594–602. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00219. [Lee VH, Lam KO, Chang AT, et al. Management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: is adjuvant therapy needed[J]? J Oncol Pract, 2018, 14 (10): 594-602.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Q, Zhou LY, Lv D, et al. Exosome-mediated communication in the tumor microenvironment contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0739-0. [Wu Q, Zhou LY, Lv D, et al. Exosome-mediated communication in the tumor microenvironment contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression[J]. J Hematol Oncol, 2019, 12(1): 53.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milane L, Singh A, Mattheolabakis G, et al. Exosome mediated communication within the tumor microenvironment. J Control Release. 2015;219:278–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.029. [Milane L, Singh A, Mattheolabakis G, et al. Exosome mediated communication within the tumor microenvironment[J]. J Control Release, 2015, 219: 278-94.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li WH, Li CY, Zhou T, et al. Role of exosomal proteins in cancer diagnosis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0706-8. [Li WH, Li CY, Zhou T, et al. Role of exosomal proteins in cancer diagnosis[J]. Mol Cancer, 2017, 16(1): 145.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alitalo K, Tammela T, Petrova TV. Lymphangiogenesis in development and human disease. Nature. 2005;438(7070):946–53. doi: 10.1038/nature04480. [Alitalo K, Tammela T, Petrova TV. Lymphangiogenesis in development and human disease[J]. Nature, 2005, 438(7070): 946-53.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sáinz-Jaspeado M, Claesson-Welsh L. Cytokines regulating lym-phangiogenesis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;53:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.04.003. [Sáinz-Jaspeado M, Claesson-Welsh L. Cytokines regulating lym-phangiogenesis[J]. Curr Opin Immunol, 2018, 53: 58-63.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jha SK, Rauniyar K, Jeltsch M. Key molecules in lymphatic development, function, and identification. Ann Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2018;219:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2018.05.003. [Jha SK, Rauniyar K, Jeltsch M. Key molecules in lymphatic development, function, and identification[J]. Ann Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger, 2018, 219: 25-34.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu LP, Lin CY, Liang WJ, et al. TBL1XR1 promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gut. 2015;64(1):26–36. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306388. [Liu LP, Lin CY, Liang WJ, et al. TBL1XR1 promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Gut, 2015, 64(1): 26-36.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CH, He W, Huang J, et al. LNMAT1 promotes lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer via CCL2 dependent macrophage recruitment. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06152-x. [Chen CH, He W, Huang J, et al. LNMAT1 promotes lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer via CCL2 dependent macrophage recruitment[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 3826.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Jedlicka P, Patrick AN, et al. SIX1 induces lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via upregulation of VEGF-C in mouse models of breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(5):1895–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI59858. [Wang C, Jedlicka P, Patrick AN, et al. SIX1 induces lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via upregulation of VEGF-C in mouse models of breast cancer[J]. J Clin Invest, 2012, 122(5): 1895-906.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He W, Zhong GZ, Jiang N, et al. Long noncoding RNA BLACAT2 promotes bladder cancer-associated lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(2):861–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI96218. [He W, Zhong GZ, Jiang N, et al. Long noncoding RNA BLACAT2 promotes bladder cancer-associated lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis[J]. J Clin Invest, 2018, 128(2): 861-75.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]