Abstract

目的

研究S100B抑制剂SBi4211(heptamidine)在人类免疫缺陷病毒-1(HIV-1)包膜蛋白gp120损伤中枢神经系统的作用。

方法

通过U251细胞和SH-SY5Y细胞建立非接触式星形胶质细胞-神经元共培养体系,由gp120蛋白处理U251细胞激活神经炎症反应造成神经元损伤,体外水平探讨SBi4211在gp120诱导的中枢神经毒性中的作用;体内实验中,以8月龄gp120转基因小鼠模拟HIV相关神经认知障碍(HAND)模型,实验分为对照组、gp120组以及gp120+SBi4211组(SBi4211处理组)。采用CCK-8、流式细胞术检测神经元活性及凋亡情况,ELISA检测S100B及炎症因子IL-6、TNF-α表达水平,Western blot和免疫组织化学染色分析RAGE、GFAP、NeuN、Syn、MAP-2蛋白表达情况。

结果

体外实验结果显示SBi4211可以显著抑制gp120刺激后U251细胞S100B、RAGE的表达(P < 0.001),降低炎症因子iNOS、IL-6和TNF-α的表达水平(P < 0.001),维持神经元相关标记蛋白NeuN、Syn的表达(P < 0.001)。体内实验结果显示SBi4211显著降低gp120转基因小鼠S100B、RAGE表达及炎症水平(P < 0.05),并且抑制脑内星形胶质细胞活化,保护神经元的完整性(P < 0.05)。

结论

SBi4211可能通过下调S100B/RAGE表达,抑制gp120引发的神经炎症反应,继而阻断gp120的中枢神经毒性作用。

Keywords: HIV-1 gp120, HAND, SBi4211, S100B/RAGE

Abstract

Objective

To explore the protective effect of SBi4211 (heptamidine), an inhibitor of S100B, against central nervous system injury induced by HIV-1 envelope protein gp120.

Methods

In an in vitro model, U251 glioma cells were co-cultured with SH-SY5Y cells to explore the protective effect of SBi4211 against gp120-induced central nervous system injury. In a gp120 transgenic (Tg) mouse model (8 months old) mimicking HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND), the effect of treatment with gp120 or both gp120 and SBi4211 on neuronal activity and apoptosis were assessed using Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and flow cytometry. ELISA, Western blotting and immunohistochemistry were used to determine the expression levels of S100B, RAGE, GFAP, NeuN, Syn, MAP-2 and the inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNF-α.

Results

In the cell co-culture system, SBi4211 treatment significantly inhibited gp120-induced expression of S100B, RAGE and GFAP in U251 cells (P < 0.001), reduced the levels of inflammatory factors iNOS, IL-6 and TNF-α (P < 0.001) and enhanced the expressions of neuron-related proteins NeuN, Syn and MAP-2 (P < 0.001). In the transgenic mouse model, SBi4211 treatment significantly reduced the expressions of S100B, RAGE and inflammation levels (P < 0.05), inhibited the activation of astrocytes in the brain, and maintained the integrity of the neurons (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

SBi4211 can protect neurons from gp120-induced neurotoxicity possibly by inhibiting the S100B/ RAGE-mediated signaling pathway.

Keywords: gp120, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, SBi4211, S100B/RAGE

随着联合抗逆转录病毒疗法(cART)的广泛应用,艾滋病已逐渐从“绝症”转变为一种可相对管控的慢性疾病[1]。HIV-1病毒感染早期采用cART可抑制病毒复制,延缓疾病的进展,并延长感染者预期寿命。然而,HIV-1长期感染的并发症,如中枢神经系统疾病等的管理仍是医疗行业面临的一个挑战[2]。HIV-1在感染早期即可侵犯中枢神经系统(CNS)[3],产生的神经炎症和神经毒性可诱发HIV-1相关神经变性及随后的相关神经认知障碍(HAND)。尽管目前已广泛应用cART,但HAND的患病率仍持续增加[4]。事实上,仍约有52%的HIV感染者被诊断为HAND[5]。因此,及早对HIV/ AIDS感染者CNS损伤进行评估及干预,对提高其生存质量具有重要意义。

研究表明,HIV的包膜蛋白HIV-1 gp120可以介导病毒进入宿主细胞,激活星形胶质细胞,并通过多种途径刺激神经毒性产物的释放,提示星形胶质细胞在HAND的发病机制中具有重要作用[6-9]。动物实验和临床研究显示,gp120在CNS损伤过程中,可增强脑组织和脑脊液中S100B的表达[10-11]。S100B是一种与损伤相关的双向调节蛋白,在大脑中主要是由星形胶质细胞分泌。当组织损伤或浓度升高时,S100B可通过与高级糖基化终产物受体(RAGE)结合,在不同的神经疾病中激活信号转导级联,诱发神经炎症继而损伤神经元[12-13]。考虑到对星形胶质细胞功能障碍和血脑屏障(BBB)破坏的特异性,S100B被认为是HIV感染后CNS和BBB损伤的生物标志物[14]。

目前,针对CNS炎性反应和新陈代谢的辅助治疗是治疗HAND的新方法[15]。SBi4211是在现有药物喷他脒(Pentamidine)的基础上,通过分子改造合成作用于S100B同一结合区域的新型化合物,具有更强的S100B抑制作用,广泛应用于治疗黑素瘤等S100B相关的癌症[16-17]。陆续也有研究发现喷他脒可以保护小鼠免于盲肠结扎穿孔术或阿尔兹海默症引起的脑损伤[18-19]。但对新型化合物SBi4211在HIV-1 gp120诱导的神经系统损伤中的作用未见报道。因此,本研究将构建U251细胞、SH-SY5Y细胞共培养模型和gp120转基因小鼠模型[20-21],从神经炎症水平和神经系统损伤方面,探究SBi4211对gp120诱导的脑损伤进程的作用及潜在机制。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 材料

1.1.1. 细胞

选用SH-SY5Y细胞系(人神经母细胞瘤细胞)和U251细胞系(人星形胶质细胞)作为研究对象,均购自中国科学院上海细胞库。

1.1.2. 实验动物

gp120转基因小鼠(雄性,7~8周龄)由美国南加州大学洛杉矶儿童医院Saban研究所友情馈赠,在南方医科大学实验动物中心繁殖并鉴定。相同遗传背景的野生型C57BL/6小鼠购买于南方医科大学实验动物中心,作为正常对照组。动物实验规程和程序已获批准,符合南方医科大学动物实验伦理委员会的伦理标准。

1.1.3. 主要仪器与试剂

恒温培养箱(赛默飞世尔科技公司)、酶标仪(Tecan)、Tanon 5500全自动化学发光成像分析系统(天能科技有限公司)、多功能酶标仪(Bio-Rad)、普通倒置显微镜(奥林巴斯光学工业)、荧光显微镜(尼康有限公司)、SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳仪(伯乐生物技术有限公司)、流式细胞仪(贝克曼库尔特有限公司)。

1640培养基(赛默飞世尔科技);胎牛血清(FBS)(PAN生物科技);青霉素-链霉素双抗混合液(Gibco);胰酶细胞消化液(Thermo Fisher);SBi4211(KareBayBioChem Inc);gp120蛋白(赛诺菲蛋白质科学公司);iNOS多克隆抗体、NeuN多克隆抗体、Synaptophsin多克隆抗体、S100B ELISA试剂盒均(武汉三鹰生物科技);gp120多克隆抗体、Iba-1多克隆抗体(Abcam);RAGE多克隆抗体(北京博奥森生物技术);细胞计数试剂盒-8(CCK-8)(东仁化学科技);Hoechst33342染色剂和Annexin V-FITC细胞凋亡检测试剂盒(碧云天);Transwell共培养板(0.4 μm)(Corning)。

1.2. 方法

1.2.1. 建立细胞共培养体系

在体外环境模拟宿主神经系统内环境,构建星形胶质细胞系U251与神经元细胞系SH-SY5Y的共培养模型。分别取复苏后第3代U251细胞和SH-SY5Y细胞,调整细胞状态,用RPMI 1640培养液重悬后,调整细胞密度为1×105/mL。在共培养孔板下层,加入调整SH-SY5Y细胞数为1×105/mL的RPMI 1640培养液600 μL,在另一含600 μL RPMI 1640培养液的孔板内放入孔径为0.4 μm Transwell小室,小室内加入调整U251细胞数为1×105/mL的RPMI 1640培养液100 μL,进行分组处理:对照组,U251细胞培养6 h后,将小室连同培养液转移至长有SH-SY5Y细胞的孔板中继续共同培养36 h;gp120组,U251细胞培养6 h后,将小室连同培养液转移至长有SH-SY5Y细胞的孔板中加入最终浓度为30 ng/mL的gp120蛋白,继续共同培养36 h;SBi4211处理组,加入浓度为0.8 μmol/L的SBi4211,预处理U251细胞6 h后,将小室连同培养液转移至长有SH-SY5Y细胞的孔板中再加入最终浓度为30 ng/mL的gp120蛋白,继续共同培养36 h[22]。分别收集细胞和上层培养液,待测。

1.2.2. 动物实验分组及处理

采用随机数字表法分别将5只对照小鼠和10只gp120转基因小鼠设为对照组,gp120组和SBi4211处理组,5只/组。SBi4211给药组按照2.5 mg /kg体质量剂量配置SBi4211溶液,采用腹腔注射方式,每次0.2 mL/只;对照组和gp120组腹腔注射等体积PBS溶液,给药频率为1次/3 d,连续给药60 d。到达实验终点,采用2%戊巴比妥纳40 mg/kg腹腔注射麻醉,在深度麻醉状态下心脏采血并快速断头取脑。取血后静置30 min 4 ℃,3000 r/min离心15 min,分离后取上清液,-80 ℃冷冻备用。脑组织置于4 ℃的4%多聚甲醛中固定24 h后,常规石蜡包埋。

1.2.3. ELISA检测S100B及相关炎性因子水平

收集共培养细胞上清液和小鼠血清样本,按照酶联免疫试剂盒的操作说明进行操作,用酶标仪在A450 nm测量各孔的吸光度值,根据A450 nm值检测共培养细胞上清液中S100B蛋白水平和炎性因子IL-6、TNF-α水平。

1.2.4. CCK-8法检测SH-SY5Y细胞生长情况

收集共培养下室中SH-SY5Y的细胞,重悬后取100 μL接种至96孔板,每组设6个复孔,每孔加入100 μL CCK-8检测液, 培养箱中继续避光孵育2 h后,用酶标仪在A450 nm测量各孔的吸光度值,并计算细胞存活率%=(实验组A450 nm值/对照组A450 nm值)×100%。

1.2.5. 流式细胞术检测神经元凋亡水平

用不含EDTA的胰蛋白酶消化并收集各组SH-SY5Y细胞,经预冷PBS洗涤3次后,4 ℃ 800 r/min离心5 min,将细胞悬液置于流式管中,采用Annexin V-PI双染流式细胞术检测细胞凋亡率,重复实验3次。

1.2.6. 双染色法免疫荧光检测神经元凋亡水平

用不含EDTA的胰蛋白酶消化并收集各组SH-SY5Y细胞,加入4%多聚甲醛固定15 min,经预冷PBS洗涤3次。吸尽洗涤液,每孔分别加入200 μL Hoechst和PI染液,避光染色15 min,滴加抗荧光淬灭剂封片,使用荧光显微镜观察。

1.2.7. Western blot检测相关蛋白水平

分别收集Transwell共培养细胞和小鼠脑组织匀浆,加入含蛋白酶抑制剂的RIPA裂解液处理各样本,并用BCA法测定蛋白浓度并调整蛋白浓度至一致,加入5×上样缓冲液,煮沸5 min,-20 ℃保存备用。

1.2.8. 免疫组化检测脑组织相关蛋白表达水平

石蜡切片二甲苯脱蜡,梯度乙醇水化。抗原修复后3%H2O2阻断内源性过氧化物酶10 min。滴加1:100比例稀释的一抗,用PBS冲洗3次,5 min/次。加1:100比例的生物素标记二抗,37 ℃孵育10~30 min。用PBS冲洗3次,5 min/次。二氨基联苯胺显色液显色1~3 min,显微镜下控制反应。Harris苏木素液复染细胞核1 min。

1.2.9. 统计学方法

数据分析统计使用软件SPSS20.0,图表的制作采用GraphPad Prism7。多组比较数据满足正态分布和方差齐性的条件时,采用单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA),不满足条件则采用非参数检验,计量资料以均数±标准差表示,所有实验均重复至少3次,P < 0.05认为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

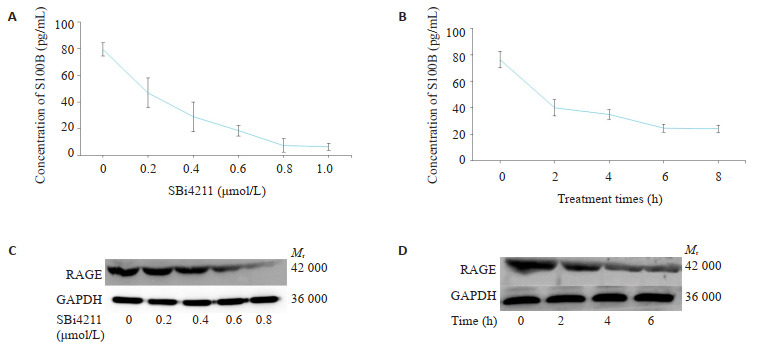

2.1. SBi4211与U251细胞表达S100B、RAGE的浓度/时间-效应关系

ELISA及Western blot结果显示,U251细胞在不同浓度SBi4211预处理6 h再经gp120诱导后,S100B和RAGE的表达水平随着SBi4211浓度增加而降低,并呈现一定的剂量依赖性。当SBi4211浓度为0.8 μmol/L时,对S100B、RAGE的表达抑制作用显著(图 1A、C)。在此基础上,采用浓度为0.8 μmol/L SBi4211探究不同处理时间对gp120诱导的U251细胞的作用效果,发现S100B、RAGE表达水平随着SBi4211处理时间增加而降低。当处理时间为6 h时,对S100B、RAGE的表达抑制效果显著(图 1B、D)。因此,接下来的实验均以0.8 μmol/L SBi4211预处理6 h作为最优处理条件。

1.

SBi4211浓度/时间依赖关系与RAGE的表达

Dose- and time-effect relationship between SBi4211 and RAGE expression in U251 cells. A: Dose-effect relationship; B: Time-effect relationship; C, D: Expression of RAGE in U251 cells detected by Western blot (Mean± SD, n=3).

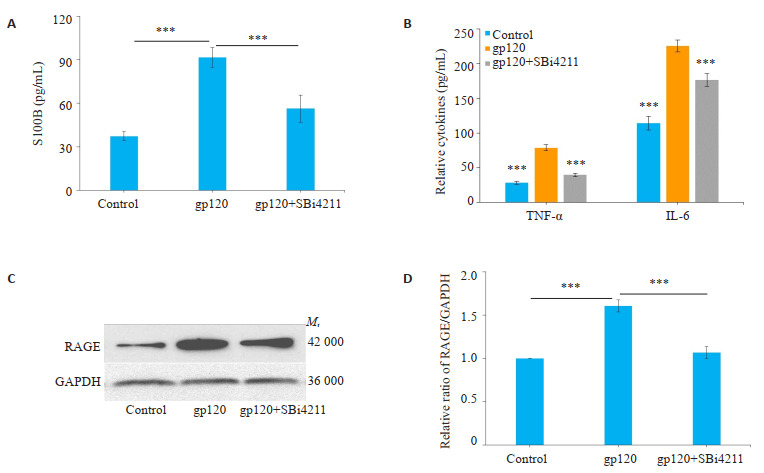

2.2. SBi4211下调共培养模型中S100B、RAGE表达水平

在体外共培养模型中,ELISA检测结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组细胞上清液S100B表达水平显著增高;与gp120组相比,SBi4211预处理可以显著下调S100B表达水平(P < 0.001,图 2A)。Western blot检测结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组U251细胞RAGE表达显著增高;与gp120组相比,SBi4211处理组RAGE表达水平显著下调(P < 0.001,图 2C)。

2.

共培养模型中S100B、RAGE表达及神经炎症水平

Expression of S100B and RAGE and inflammatory levels in the co-culture cell model. A, B: Expression of S100B, IL-6 and TNF-α in the supernatants determined by ELISA. C: Expression of RAGE in the co-culture model detected by Western blotting. Quantitative analysis of the results was carried out using Image J grayscale scanning and the results are presented as Mean±SD (n=3). ***P < 0.001 vs gp120 group

2.3. SBi4211降低共培养模型中的神经炎症水平

ELISA检测培养液上清中炎症因子释放水平,结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120处理后上清液IL-6和TNF-α水平显著增加;而SBi4211预处理后则可以显著降低IL-6和TNF-α的水平(P < 0.001,图 2B)。

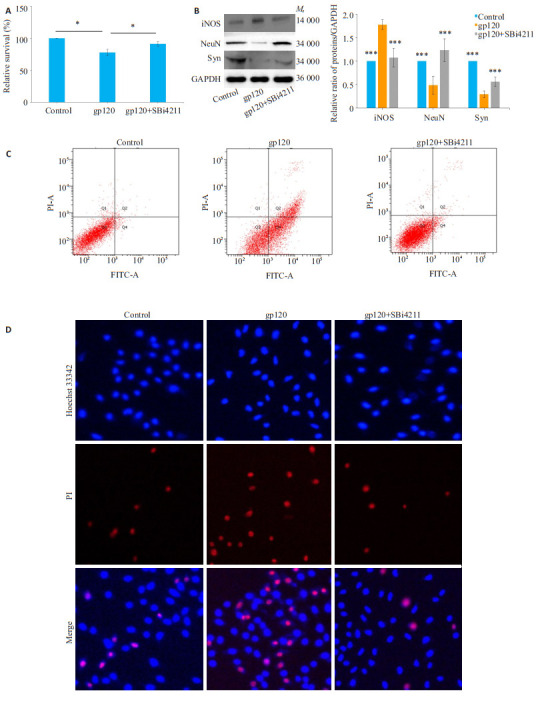

2.4. SBi4211减轻共培养模型中神经元损伤程度

通过CCK-8和流式细胞术分别检测SH-SY5Y细胞活性和凋亡情况,结果显示,经gp120处理后SHSY5Y细胞活性显著下降,凋亡细胞数量增加,而与gp120组相比,SBi4211处理组神经元活性增加、凋亡细胞数量减少(P < 0.05,图 3A、C、D)。Western blot检测结果显示,经gp120处理后NeuN(神经元标志物)和Syn(synaptophysin,突触素标志物)表达水平显著下调,而SBi4211预处理后可显著提高NeuN和Syn表达水平(P < 0.001,图 3B)。

3.

共培养模型中神经元损伤情况

Neuronal damage in the co-culture cell model. A: Viability of neurons detected by CCK-8 kit. B: Expression of neuron damage markers detected by Western blotting. C, D: Cell apoptosis analyzed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence assay (Original magnification: × 400). The results are presented as Mean ± SD (n=3). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs gp120 group.

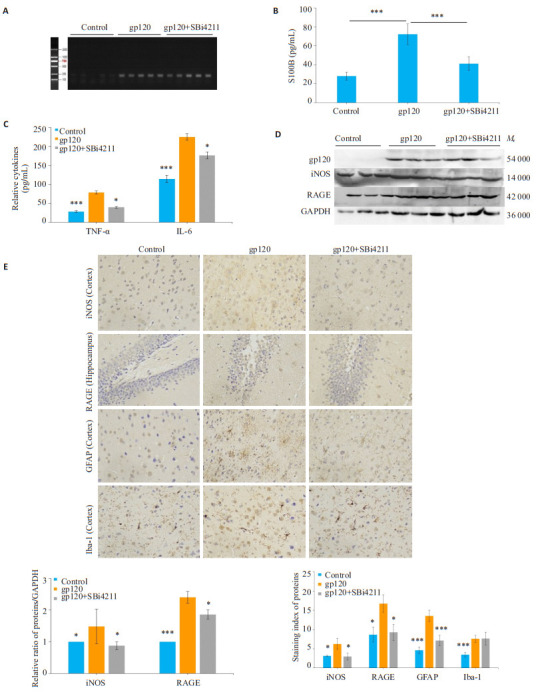

2.5. SBi4211下调gp120转基因小鼠血清S100B表达

3组小鼠gp120基因型鉴定结果显示(图 4A),1~5号小鼠基因型为gp120-即对照组,6~10号小鼠基因型为gp120+即gp120组,11~15号小鼠基因型为gp120+即SBi4211处理组。ELISA分别检测3组小鼠血清中S100B水平,结果显示gp120组小鼠血清S100B表达水平显著上升,符合S100B作为神经损伤分子标记物的理论,而gp120转基因小鼠经SBi4211处理后,S100B表达明显受到抑制(P < 0.001,图 4B)。

4.

各组小鼠S100B表达及脑组织神经炎症水平

Expression of S100B and neurological inflammation levels in different groups of mice. A: Genotyping of gp120 transgenic mice; B, C: Expression of S100B, IL-6 and TNF-α in mice determined by the ELISA; D: Expression of iNOS and RAGE detected by Western blotting; E: Immunohistochemistry for detecting iNOS, RAGE, GFAP and Iba-1 expressions in the cortex and hippocampus (×400). Quantitative analysis of the results of Western blotting and immunohistochemistry staining was performed with Image J grayscale scanning, and the results are presented as Mean±SD (n=3). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs gp120 group.

2.6. SBi4211降低gp120转基因小鼠血清及脑组织神经炎症水平

ELISA检测小鼠血清炎症因子IL-6和TNF-α表达,结果表明,与对照组相比,gp120组小鼠血清中IL-6、TNF-α分泌显著增加(P < 0.001),而SBi4211处理后,炎性因子的分泌显著降低(P < 0.05,图 4C)。脑组织Western blot检测结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组RAGE的表达显著增加(P < 0.001);与gp120组相比,SBi4211处理组RAGE表达降低(P < 0.05,图 4D)。脑组织切片免疫组化结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组小鼠iNOS、RAGE、神经胶质纤维酸性蛋白(GFAP)、Iba-1阳性信号染色较深,阳性细胞密度增加(P < 0.05),iNOS主要在胞核高表达,而GFAP、Iba-1主要在胞浆和细胞突起部分棕染;相比于gp120组,SBi4211组小鼠脑组织iNOS、RAGE、GFAP阳性信号染色较浅,阳性细胞密度降低(P < 0.05,图 4E)。

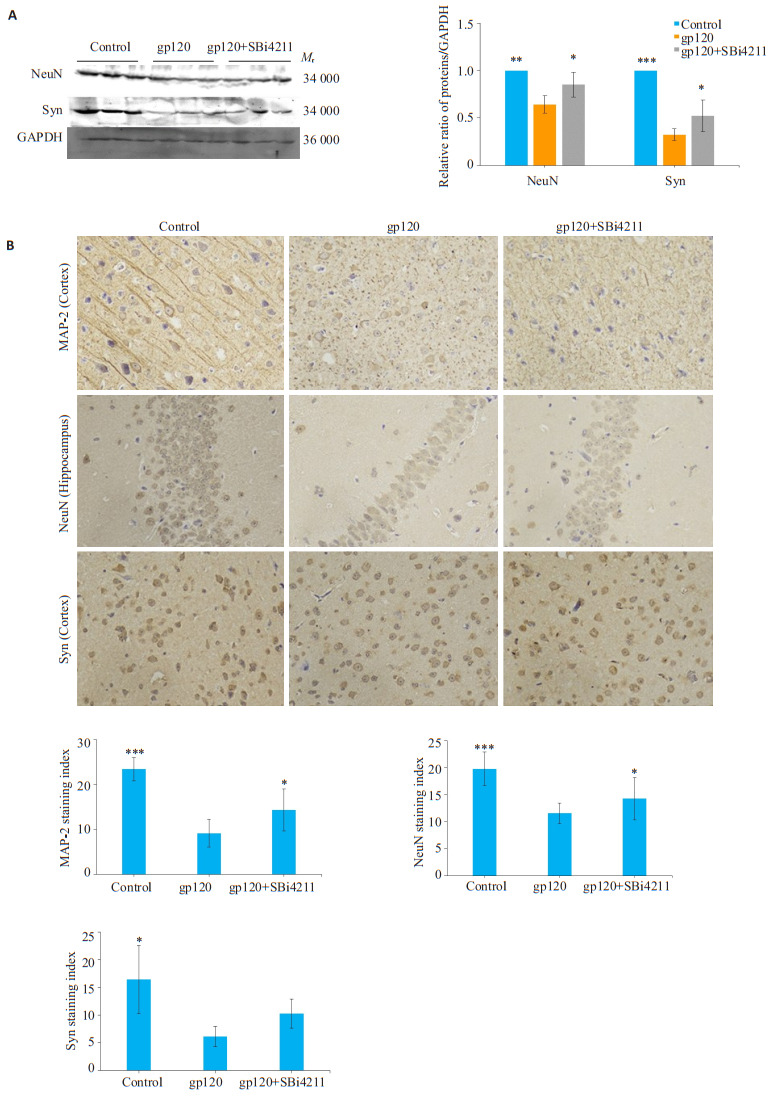

2.7. SBi4211减轻gp120转基因小鼠脑组织神经元损伤程度

MAP-2作为神经元轴突的标记蛋白,与NeuN、Syn共同检测可指示神经元的损伤程度。Western blot检测结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组小鼠脑组织NeuN、Syn表达显著降低(P < 0.01);经SBi4211处理后NeuN、Syn表达增加(P < 0.05,图 5A)。免疫组化的结果显示,与对照组相比,gp120组MAP-2、NeuN、Syn阳性信号较浅,阳性细胞减少(P < 0.05);相比于gp120组,SBi4211组小鼠脑组织MAP-2、NeuN阳性信号加深,阳性细胞增加(P < 0.05,图 5B)。其中NeuN染色主要在成熟的神经元细胞核,Syn染色主要在胞质,而MAP-2在神经元胞浆和胞核均有广泛棕染。

5.

各组小鼠中枢神经系统损伤情况

Injuries in the central nervous system of the mice in different groups. A: Expression of NeuN and Syn detected by Western blotting. B: Immunohistochemistry for detecting MAP-2, NeuN and Syn expressions in the cortex and hippocampus (×400). The results of quantitative analysis are presented as Mean±SD (n=3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs gp120 group.

3. 讨论

HIV-1包膜蛋白gp120除了由神经元表面趋化因子受体CXCR4、CCR5介导神经元凋亡与焦亡的直接神经毒性外[23-24],还可以通过刺激神经系统免疫应答、诱导释放炎性介质,激活氧化应激和改变BBB通透性等方式间接损伤神经系统[10, 25-26]。星形胶质细胞作为脑免疫作用的界面,是中枢神经系统先天免疫和适应性免疫转换的关键细胞。在HAND等病理状态下可见星形胶质细胞反应性活化增生,GFAP、S100B过表达,并伴随IL-1β、IL-6、TNF-α等促炎性因子的释放,该过程与小胶质细胞相互调节[27],共同促进疾病进程。本研究选取IL-6与TNF-α为代表性炎性介质,分析神经炎症水平;选取神经元MAP-2、NeuN、Syn作为神经元损伤标记蛋白,分析神经元损伤程度。体内实验利用gp120转基因小鼠模型,选取NeuN、Syn、GFAP、Iba-1作为检测神经退行性病变的指标[28]。GFAP是星形胶质细胞成熟的标志,对星形胶质细胞损伤具有高度特异性。体内实验中脑部免疫组织化学切片结果显示,gp120转基因小鼠GFAP表达显著上调,表明存在明显的星形胶质细胞反应性增生,上述现象均为CNS损伤后星形细胞活化反应的主要特征[29]。此外,我们还发现gp120转基因小鼠脑组织中Iba-1表达明显增多,提示出现小胶质细胞激活。目前,在多种人类神经退行性疾病中均发现[30],神经炎症性小胶质细胞可诱导星形胶质细胞活化,产生神经毒性,同时引起神经元和少突胶质细胞死亡。

体内外实验均证实,在gp120蛋白刺激下,星形胶质细胞会出现活化现象并伴随S100B、RAGE蛋白以及相关炎症因子IL-6、TNF-α的表达水平增加。S100B是一种主要表达于中枢神经系统星形胶质细胞的Ca2+结合蛋白,在细胞能量代谢、骨架重排、增殖和分化等方面具有重要作用。在正常生理浓度下,S100B对神经元有营养作用,但高剂量下会诱导宿主细胞释放炎性因子,已被证实能导致神经炎症和进一步的损伤[13]。此外,大量临床研究发现,患有晚期神经认知障碍的HIV感染者脑脊液中S100B以游离和外泌体结合形式呈现高表达[31]。我们前期研究表明gp120在BBB损伤过程中可增强α7 nAChR依赖性淀粉性蛋白、S100B和RAGE的表达[10]。现有研究提示该神经损伤过程依赖于S100B与RAGE的结合[32]。RAGE是晚期糖基化终产物的细胞表面受体,在星形胶质细胞、小胶质细胞和神经元中均有表达。RAGE可作为细胞粘附分子,参与识别病原微生物感染、应激或慢性炎症中释放的内源性分子,同时也具有识别一些损伤相关分子模式分子的能力。现有研究发现,RAGE在细胞和组织中加速积累时,会产生淀粉样蛋白,形成神经原纤维缠结,导致阿尔茨海默症病理改变加重。RAGE还可以与S100蛋白结合刺激RAGE依赖的信号级联,在高剂量时能触发细胞凋亡程序,诱发NADPH氧化酶应激,形成活性氧中间产物,激活NF- κB和基因转录等一系列神经炎症级联反应最终导致神经认知障碍[33-34]。由此可见S100B/RAGE可能在扩大gp120诱导的HAND神经炎症及损伤中具有重要意义。

由于HAND发病机制及治疗方案尚未完全明确,研发可以预测HAND进展的特异性生物标志物并针对性予以干预,将是目前研究的重要方向。针对小分子靶点的治疗现仍处于早期阶段。相关研究发现CNS炎性反应、神经酰胺代谢和内溶酶体功能的调节物都可能是干预治疗的潜在靶点[35-36]。美国vTv Therapeutics公司于2019年启动了一项为期18个月的3期临床试验以检测新型口服RAGE活性小分子拮抗剂Azeliragon(TTP 488)对轻度阿尔茨海默病患者的安全性和有效性[37]。喷他脒的同系物SBi4211已通过临床试验并证实可用于黑色素瘤的治疗,并且定向抑制S100B的能力更强,其机制可能与抑制S100B与p53的相互作用从而阻断S100B的活性有关,但不能排除直接对S100B/RAGE的抑制的可能[18, 38]。研究表明,抑制S100B及RAGE蛋白可下调炎性相关基因的表达[39]。基于此前研究结果,本研究采用SBi4211干预gp120诱导模型发现,gp120诱导的神经炎症水平(IL-6、TNF-α、iNOS)、神经系统损伤(星形胶质细胞及小胶质细胞活化,神经元损伤)经SBi4211处理后均得到一定程度的改善,同时伴随着S100B、RAGE表达的降低,但SBi4211具体的作用靶点及机制还需进一步研究来证实。

综上所述,本研究初步证实了SBi4211对gp120感染所致中枢神经系统损伤具有改善作用,可能与抑制S100B/RAGE介导的神经炎症相关通路有关。基于HAND发病的复杂性,最终的治疗方案可能是多种机制的不同药物的联用。SBi4211可能是潜在的有效干预药物,虽不能逆转任何已有的损伤,但仍可减缓疾病的发生进程,这一研究结果将为HAND新型治疗方案提供思路。

Biography

杨少杰,硕士,E-mail: 362408905@qq.com

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金(81370740,81873762,81871198);广东省自然科学基金重点项目(2017B030311017);湖南省科技计划重点研发项目(2018SK2069)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370740, 81873762, 81871198)

Contributor Information

杨 少杰 (Shaojie YANG), Email: 362408905@qq.com.

龙 北国 (Beiguo LONG), Email: 2621324716@qq.com.

黄 胜和 (Shenghe HUANG), Email: shhuang18@hotmail.edu.

References

- 1.Daniel Elbirt MD, Keren Mahlab-Guri MD, Shira BezalelRosenberg MD, et al. Hiv-associated neurocognitive disorders (Hand) IMAJ. 2015;17(7):54–9. [Daniel Elbirt MD, Keren Mahlab-Guri MD, Shira BezalelRosenberg MD, et al. Hiv-associated neurocognitive disorders (Hand)[J]. IMAJ, 2015, 17(7): 54-9.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.TEMPRANO ANRS Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. [TEMPRANO ANRS Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(9): 808-22.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gougeon ML. Alarmins and central nervous system inflammation in HIV-associated neurological disorders. J Intern Med. 2017;281(5):433–47. doi: 10.1111/joim.12570. [Gougeon ML. Alarmins and central nervous system inflammation in HIV-associated neurological disorders[J]. J Intern Med, 2017, 281 (5): 433-47.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors[J]. J Neurovirol, 2011, 17(1): 3-16.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study[J]. Neurology, 2010, 75(23): 2087-96.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RA, Seider TR, Navia B. HIV effects on age-associated neurocognitive dysfunction: premature cognitive aging or neurodegenerative disease? Alz Res Therapy. 2015;(21):7–37. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0123-4. [Cohen RA, Seider TR, Navia B. HIV effects on age-associated neurocognitive dysfunction: premature cognitive aging or neurodegenerative disease[J]? Alz Res Therapy, 2015, (21)7: 37.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaurin KA, Li HL, Booze RM, et al. Disruption of timing: NeuroHIV progression in the post-cART era. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):827. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36822-1. [McLaurin KA, Li HL, Booze RM, et al. Disruption of timing: NeuroHIV progression in the post-cART era[J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9 (1): 827.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez M, Lapierre J, Ojha CR, et al. Importance of autophagy in mediating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and morphineinduced metabolic dysfunction and inflammation in human astrocytes. Viruses. 2017;9(8):E201. doi: 10.3390/v9080201. [Rodriguez M, Lapierre J, Ojha CR, et al. Importance of autophagy in mediating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and morphineinduced metabolic dysfunction and inflammation in human astrocytes[J]. Viruses, 2017, 9(8): E201.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy PV, Gandhi N, Samikkannu T, et al. HIV-1 gp120 induces antioxidant response element-mediated expression in primary astrocytes: role in HIV associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurochem Int. 2012;61(5):807–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.06.011. [Reddy PV, Gandhi N, Samikkannu T, et al. HIV-1 gp120 induces antioxidant response element-mediated expression in primary astrocytes: role in HIV associated neurocognitive disorder[J]. Neurochem Int, 2012, 61(5): 807-14.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu LQ, Yu JY, Li L, et al. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for amyloid pathology in brain endothelial cells induced by Glycoprotein 120, methamphetamine and nicotine. Sci Rep. 2017;7(2):40467. doi: 10.1038/srep40467. [Liu LQ, Yu JY, Li L, et al. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is required for amyloid pathology in brain endothelial cells induced by Glycoprotein 120, methamphetamine and nicotine[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(2): 40467.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pemberton LA, Brew BJ. Cerebrospinal fluid S-100beta and its relationship with AIDS dementia complex. J Clin Virol. 2001;22(3):249–53. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00196-2. [Pemberton LA, Brew BJ. Cerebrospinal fluid S-100beta and its relationship with AIDS dementia complex[J]. J Clin Virol, 2001, 22 (3): 249-53.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michetti F, D'Ambrosi N, Toesca A, et al. The S100B story: from biomarker to active factor in neural injury. J Neurochem. 2019;148(2):168–87. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14574. [Michetti F, D'Ambrosi N, Toesca A, et al. The S100B story: from biomarker to active factor in neural injury[J]. J Neurochem, 2019, 148(2): 168-87.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piazza O, Leggiero E, de Benedictis G, et al. S100B induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in alveolar type I-like cells. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2013;26(2):383–91. doi: 10.1177/039463201302600211. [Piazza O, Leggiero E, de Benedictis G, et al. S100B induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in alveolar type I-like cells [J]. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol, 2013, 26(2): 383-91.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahimian P, He JJ. HIV/neuroAIDS biomarkers. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;157(8):117–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.04.003. [Rahimian P, He JJ. HIV/neuroAIDS biomarkers[J]. Prog Neurobiol, 2017, 157(8): 117-32.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.聂 静敏, 蔡 卫平, 郭 朋乐, et al. 人类免疫缺陷病毒相关神经认知障碍的发病机制及治疗进展. 中华传染病杂志. 2017;35(4):251–3. [聂静敏, 蔡卫平, 郭朋乐, 等.人类免疫缺陷病毒相关神经认知障碍的发病机制及治疗进展[J].中华传染病杂志, 2017, 35(4): 251-3.] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKnight LE, Raman EP, Bezawada P, et al. Structure-based discovery of a novel pentamidine-related inhibitor of the calciumbinding protein S100B. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3(12):975–9. doi: 10.1021/ml300166s. [McKnight LE, Raman EP, Bezawada P, et al. Structure-based discovery of a novel pentamidine-related inhibitor of the calciumbinding protein S100B[J]. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2012, 3(12): 975-9.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavalier MC, Weber DJ. Targeting melanoma with small molecules: inhibitors of the calcium-binding protein S100B. Biophys J. 2015;108(2):214a. [Cavalier MC, Weber DJ. Targeting melanoma with small molecules: inhibitors of the calcium-binding protein S100B[J]. Biophys J, 2015, 108(2): 214a.] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L, Zhang LN, Liu ZY, et al. Pentamidine protects mice from cecal ligation and puncture-induced brain damage via inhibiting S100B/RAGE/NF-κB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;517(2):221–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.045. [Huang L, Zhang LN, Liu ZY, et al. Pentamidine protects mice from cecal ligation and puncture-induced brain damage via inhibiting S100B/RAGE/NF-κB[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019, 517(2): 221-6.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cirillo C, Capoccia E, Iuvone T, et al. S100B inhibitor pentamidine attenuates reactive gliosis and reduces neuronal loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:508342. doi: 10.1155/2015/508342. [Cirillo C, Capoccia E, Iuvone T, et al. S100B inhibitor pentamidine attenuates reactive gliosis and reduces neuronal loss in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 508342.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandes A, Ribeiro AR, Monteiro M, et al. Secretome from SHSY5Y APPSwe cells trigger time-dependent CHME3 microglia activation phenotypes, ultimately leading to miR-21 exosome shuttling. Biochimie. 2018;155(7):67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.05.015. [Fernandes A, Ribeiro AR, Monteiro M, et al. Secretome from SHSY5Y APPSwe cells trigger time-dependent CHME3 microglia activation phenotypes, ultimately leading to miR-21 exosome shuttling [J]. Biochimie, 2018, 155(7): 67-82.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thaney VE, Sanchez AB, Fields JA, et al. Transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 in the brain as an animal model in neuroAIDS research. J Neurovirol. 2018;24(2):156–67. doi: 10.1007/s13365-017-0584-2. [Thaney VE, Sanchez AB, Fields JA, et al. Transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 in the brain as an animal model in neuroAIDS research[J]. J Neurovirol, 2018, 24(2): 156-67.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.魏 轶, 彭 亮, 李 莉, et al. SBi4211阻断HIV-1 gp41促进新生隐球菌对人脑微血管内皮细胞的黏附作用. 微生物学通报. 2019;46(6):1496–501. [魏轶, 彭亮, 李莉, 等. SBi4211阻断HIV-1 gp41促进新生隐球菌对人脑微血管内皮细胞的黏附作用[J].微生物学通报, 2019, 46(6): 1496-501.] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaul M, Ma Q, Medders KE, et al. HIV-1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 both mediate neuronal cell death but CCR5 paradoxically can also contribute to protection. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(2):296–305. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402006. [Kaul M, Ma Q, Medders KE, et al. HIV-1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 both mediate neuronal cell death but CCR5 paradoxically can also contribute to protection[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2007, 14(2): 296-305.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He XL, Yang WJ, Zeng ZJ, et al. NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis is required for HIV-1 gp120-induced neuropathology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(3):283–99. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0260-y. [He XL, Yang WJ, Zeng ZJ, et al. NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis is required for HIV-1 gp120-induced neuropathology[J]. Cell Mol Immunol, 2020, 17(3): 283-99.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronaldson PT, Bendayan R. HIV-1 viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 produces oxidative stress and regulates the functional expression of multidrug resistance protein-1 (Mrp1) in glial cells. J Neurochem. 2008;106(3):1298–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05479.x. [Ronaldson PT, Bendayan R. HIV-1 viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 produces oxidative stress and regulates the functional expression of multidrug resistance protein-1 (Mrp1) in glial cells[J]. J Neurochem, 2008, 106(3): 1298-313.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaul M, Lipton SA. Chemokines and activated macrophages in HIV gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(14):8212–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8212. [Kaul M, Lipton SA. Chemokines and activated macrophages in HIV gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1999, 96(14): 8212-6.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrak RE, Griffinbc WS. The role of activated astrocytes and of the neurotrophic cytokine S100B in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22(6):915–22. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00293-7. [Mrak RE, Griffinbc WS. The role of activated astrocytes and of the neurotrophic cytokine S100B in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2001, 22(6): 915-22.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fields JA, Overk C, Adame A, et al. Neuroprotective effects of the immunomodulatory drug FK506 in a model of HIV1-gp120 neurotoxicity. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0585-8. [Fields JA, Overk C, Adame A, et al. Neuroprotective effects of the immunomodulatory drug FK506 in a model of HIV1-gp120 neurotoxicity[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2016, 13(1): 120.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes FC, Paulin D, Moura Neto V. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP): modulation by growth factors and its implication in astrocyte differentiation. Revista Brasileira De Pesquisas Med E Biol. 1999;32(5):619–31. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1999000500016. [Gomes FC, Paulin D, Moura Neto V. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP): modulation by growth factors and its implication in astrocyte differentiation[J]. Revista Brasileira De Pesquisas Med E Biol, 1999, 32(5): 619-31.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.温 彩燕. 神经毒性反应性星形胶质细胞是由活化的小胶质细胞诱导的. 中国病理生理杂志. 2018;34(10):1777. [温彩燕.神经毒性反应性星形胶质细胞是由活化的小胶质细胞诱导的[J].中国病理生理杂志, 2018, 34(10): 1777.] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guha D, Mukerji SS, Chettimada S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles and neurofilament light protein as biomarkers of central nervous system injury in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2019;33(4):615–25. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002121. [Guha D, Mukerji SS, Chettimada S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles and neurofilament light protein as biomarkers of central nervous system injury in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy[J]. AIDS, 2019, 33(4): 615-25.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villarreal A, Aviles Reyes RX, Angelo MF, et al. S100B alters neuronal survival and dendrite extension via RAGE-mediated NF- κB signaling. J Neurochem. 2011;117(2):321–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07207.x. [Villarreal A, Aviles Reyes RX, Angelo MF, et al. S100B alters neuronal survival and dendrite extension via RAGE-mediated NF- κB signaling[J]. J Neurochem, 2011, 117(2): 321-32.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai ZY, Liu NN, Wang CL, et al. Role of RAGE in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(4):483–95. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0233-3. [Cai ZY, Liu NN, Wang CL, et al. Role of RAGE in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2016, 36(4): 483-95.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarreal A, Seoane R, González Torres A, et al. S100B protein activates a RAGE-dependent autocrine loop in astrocytes: implications for its role in the propagation of reactive gliosis. J Neurochem. 2014;131(2):190–205. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12790. [Villarreal A, Seoane R, González Torres A, et al. S100B protein activates a RAGE-dependent autocrine loop in astrocytes: implications for its role in the propagation of reactive gliosis[J]. J Neurochem, 2014, 131(2): 190-205.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin SS, Chen Q, Wu H, et al. Effects of naringin on learning and memory dysfunction induced by gp120 in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2016;124(8):164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.020. [Qin SS, Chen Q, Wu H, et al. Effects of naringin on learning and memory dysfunction induced by gp120 in rats[J]. Brain Res Bull, 2016, 124(8): 164-71.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bae M, Patel N, Xu HX, et al. Activation of TRPML1 clears intraneuronal Aβ in preclinical models of HIV infection. J Neurosci. 2014;34(34):11485–503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0210-14.2014. [Bae M, Patel N, Xu HX, et al. Activation of TRPML1 clears intraneuronal Aβ in preclinical models of HIV infection[J]. J Neurosci, 2014, 34(34): 11485-503.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kriebel-Gasparro A. Update on Treatments for Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. J Nur Practition. 2020;16(3):181–5. [Kriebel-Gasparro A. Update on Treatments for Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease[J]. J Nur Practition, 2020, 16(3): 181-5.] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshimura C, Miyafusa T, Tsumoto K. Identification of smallmolecule inhibitors of the human S100B-p53 interaction and evaluation of their activity in human melanoma cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(5):1109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.042. [Yoshimura C, Miyafusa T, Tsumoto K. Identification of smallmolecule inhibitors of the human S100B-p53 interaction and evaluation of their activity in human melanoma cells[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2013, 21(5): 1109-15.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano A, Donno C, Giannetti S, et al. The astrocytic S100B protein with its receptor RAGE is aberrantly expressed in SOD1G93A models, and its inhibition decreases the expression of proinflammatory genes. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:1626204. doi: 10.1155/2017/1626204. [Serrano A, Donno C, Giannetti S, et al. The astrocytic S100B protein with its receptor RAGE is aberrantly expressed in SOD1G93A models, and its inhibition decreases the expression of proinflammatory genes [J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2017, 2017: 1626204.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]