Key Points

Question

Is Agent Orange exposure associated with an increased risk of dementia diagnosis in US veterans of the Vietnam era?

Findings

In this study of more than 300 000 veterans, those with Agent Orange exposure in their medical records were nearly twice as likely as those without exposure to receive a dementia diagnosis, even after adjusting for medical and psychiatric comorbidities and other variables.

Meaning

Per this analysis, Agent Orange exposure may increase risk of dementia.

This study examines the association between Agent Orange exposure and incident dementia diagnosis among US veterans who served in the Vietnam era.

Abstract

Importance

Agent Orange is a powerful herbicide that contains dioxin and was used during the Vietnam War. Although prior studies have found that Agent Orange exposure is associated with increased risk of a wide range of conditions, including neurologic disorders (eg, Parkinson disease), metabolic disorders (eg, type 2 diabetes), and systemic amyloidosis, the association between Agent Orange and dementia remains unclear.

Objective

To examine the association between Agent Orange exposure and incident dementia diagnosis in US veterans of the Vietnam era.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study included Veterans Health Administration data from October 1, 2001, and September 30, 2015, with up to 14 years of follow-up. Analyses were performed from July 2018 to October 2020. A 2% random sample of US veterans of the Vietnam era who received inpatient or outpatient Veterans Health Administration care, excluding those with dementia at baseline, those without follow-up visits, and those with unclear Agent Orange exposure status.

Exposures

Presumed Agent Orange exposure documented in electronic health record.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Fine-Gray competing risk models were used to compare the time to dementia diagnosis (with age as the time scale) for veterans with vs without presumed Agent Orange exposure (as per medical records), adjusting for demographic variables and medical and psychiatric comorbidities.

Results

The total sample was 511 189 individuals; after exclusions, 316 351 were included in analyses. Veterans were mostly male (n = 309 889 [98.0%]) and had a mean (SD) age of 62 (6.6) years; 38 121 (12.1%) had presumed Agent Orange exposure. Prevalence of most conditions, including Parkinson disease, diabetes, and amyloidosis, was similar at baseline among veterans with and without Agent Orange exposure. After adjusting for demographic variables and comorbidities, veterans exposed to Agent Orange were nearly twice as likely as those not exposed to receive a dementia diagnosis over a mean (SD) of 5.5 (3.8) years of follow-up (1918 of 38 121 [5.0%] vs 6886 of 278 230 [2.5%]; adjusted hazard ratio: 1.68 [95% CI, 1.59-1.77]). Veterans with Agent Orange exposure developed dementia at a mean of 1.25 years earlier (at a mean [SD] age of 67.5 [7.0] vs 68.8 [8.0] years).

Conclusions and Relevance

Veterans with Agent Orange exposure were nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with dementia, even after adjusting for the competing risk of death, demographic variables, and medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Additional studies are needed to examine potential mechanisms underlying the association between Agent Orange exposure and dementia.

Introduction

Agent Orange is a powerful herbicide that was used by US forces during the Vietnam War to remove trees and vegetation that provided enemy cover.1 It includes the active ingredient 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T), as well as traces of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (dioxin or TCDD), which is highly toxic and was classified as a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 1997.2

Since 1994, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has periodically performed comprehensive literature reviews on the health effects of Agent Orange. The most recent 2018 report1 concluded that there is sufficient evidence linking Agent Orange with a wide range of adverse health outcomes, including neurologic disorders (Parkinson disease), metabolic disorders (type 2 diabetes), cardiovascular disorders (ischemic heart disease), and systemic amyloidosis. Although evidence of an association between Agent Orange exposure and dementia was considered insufficient, dementia is a growing concern among veterans (a 20% increase by 2033), with military-relevant conditions found to be particularly salient risk factors (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], traumatic brain injury).3,4,5,6 The goal of this study was to examine the association between Agent Orange exposure and dementia diagnosis in US veterans of the Vietnam era.

Methods

Patient Population

Data were extracted from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) National Patient Care Database, an electronic database for all VHA inpatient and outpatient encounters. Participants included a 2% random sample of veterans from the Vietnam era, as defined by period of military service (August 5, 1964, to May 7, 1975), who received VHA care between October 1, 2001, and September 30, 2015. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco; the Research & Development Committee at the San Francisco VA Medical Center; and the Human Research Protection Office of the US Army Medical Research and Materiel command. The need for informed consent was waived because of the use of deidentified administrative data.

Measures

Agent Orange Exposure

Two variables were used to define presumptive Agent Orange exposure: (1) patient self-report of Vietnam service with exposure to Agent Orange (inpatient files; all study years) and (2) a clinician indicator that a health care encounter was associated with Agent Orange exposure (in outpatient files, from October 2002 to September 2015; in inpatient files, from October 2005 to September 2015). Individuals who only met 1 of the defining criteria were excluded.

Dementia

Dementia at baseline was defined using previously defined International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes to maximize sensitivity,7,8 and those with prevalent dementia were excluded. Dementia at follow-up was defined using a restricted set of codes to maximize specificity.5

Other Measures

Demographic variables included age and sex. Socioeconomic status was determined based on neighborhood education and income data from the 2000 US Census. Codes from the ICD-9 were used to identify veterans with specific medical diagnoses (diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, traumatic brain injury, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, and obesity) and psychiatric diagnoses (PTSD, major depressive disorder, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and tobacco use) at baseline.4 Those without follow-up visits were excluded from analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of veterans with and without Agent Orange exposure documented in their medical records were compared using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables. Fine-Gray competing risk models examined time to dementia onset with age as the time scale and accounting for death as a competing risk. Time to event was calculated from the date of random selection until the date of dementia diagnosis, death, or the last health care visit until the end of the study period (September 30, 2015). Models were unadjusted and adjusted for potential confounders that were significantly associated with Agent Orange in bivariate analyses. The significance threshold was P < .05, 2-tailed. Analysis was completed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and Stata/MP version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Of the initial 511 189 eligible participants, 194 838 were excluded, for a final sample size of 316 351 (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Veterans were mostly male (n = 309 889 [98.0%]) and had a mean (SD) age of 62 (6.6) years. There were minimal differences between excluded and included participants (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Of the 316 351 veterans of the Vietnam era studied, 50 250 (15.9%) died during follow-up. A total of 38 121 veterans (12.1%) reported a history of exposure to Agent Orange at baseline. Veterans exposed to Agent Orange were slightly younger (mean [SD] ages: with Agent Orange exposure, 61.9 [5.5] years; without exposure, 62.6 [6.8] years; P < .001) and were less likely to be women (with Agent Orange exposure: 57 women of 38 121 individuals [0.2%]; without exposure: 6405 women of 278 230 individuals [2.3%]; P < .001) (Table 1). Prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions was higher in veterans with vs without Agent Orange exposure, including depression (5239 of 38 121 [13.7%] vs 23 472 of 278 230 [8.4%]; P < .001) and substance use disorder (2882 of 38 121 [7.6%] vs 14 767 of 278 230 [5.3%]; P < .001). Notably, prevalence of PTSD was nearly 3 times higher for veterans with vs without Agent Orange exposure (3811 of 38 121 [10.0%] vs 8967 of 278 230 [3.2%]; P < .001).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of 316 351 Vietnam Veterans by Agent Orange Exposurea.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Agent Orange exposure (n = 278 230) | Agent Orange exposure (n = 38 121) | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.55 (6.78) | 61.89 (5.54) | <.001 |

| Female, No. (%) | 6405 (2.30) | 57 (0.15) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | <.001 | ||

| White | 210 250 (75.57) | 29 858 (78.32) | |

| Black | 37 308 (13.41) | 5845 (15.33) | |

| Hispanic | 2308 (0.83) | 534 (1.40) | |

| American Indian | 1253 (0.45) | 238 (0.62) | |

| Asian | 1365 (0.49) | 100 (0.26) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 267 (0.10) | 19 (0.05) | |

| Declined/unknown | 25 479 (9.16) | 1527 (4.01) | |

| >25% College-educated in zip codeb | 127 063 (45.67) | 15 804 (41.46) | <.001 |

| Low-tertile (<$24 632) income in zip codeb | 70 728 (25.42) | 10 402 (27.29) | <.001 |

| Medical | |||

| Diabetes | 25 605 (9.20) | 3964 (10.40) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 54 516 (19.59) | 7058 (18.51) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5539 (1.99) | 1428 (3.75) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8489 (3.05) | 1884 (4.94) | <.001 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 5385 (1.94) | 1448 (3.80) | <.001 |

| Parkinson disease | 661 (0.24) | 131 (0.34) | <.001 |

| Psychiatric | |||

| Depression | 23 472 (8.44) | 5239 (13.74) | <.001 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 8967 (3.22) | 3811 (10.00) | <.001 |

| Substance use disorder | 14 767 (5.31) | 2882 (7.56) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 28 102 (10.10) | 4598 (12.06) | <.001 |

| Sleep disorder | 6555 (2.36) | 1626 (4.27) | <.001 |

| Follow-up, mean (SD), y | 5.40 (3.76) | 5.95 (3.82) | <.001 |

The P values are based on unpaired t test for age and χ2 test for other variables.

Education has 12 458 missing values (3.94%), and income has 12 399 missing values (3.92%).

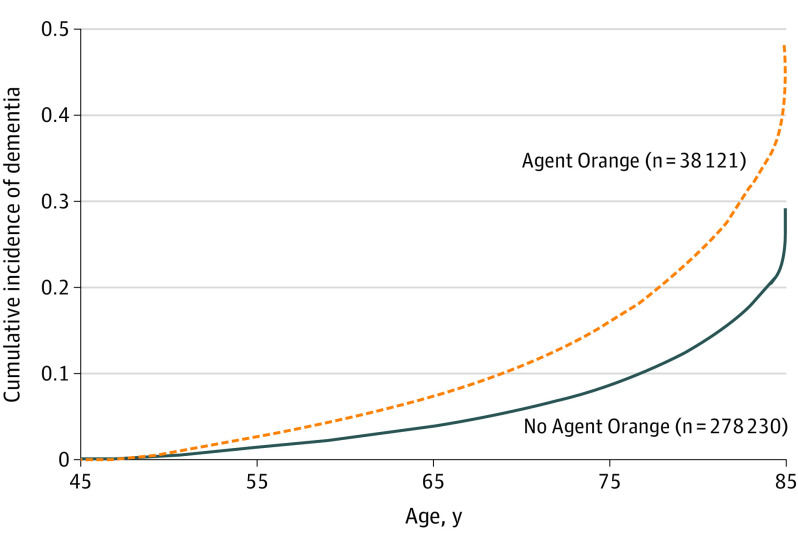

Veterans were followed up for a mean (SD) of 5.5 (3.8) years. Differences in the cumulative incidence of dementia diagnosis during the 14-year follow-up period in those with and without Agent Orange exposure are shown in the Figure. In unadjusted analyses, the risk of dementia was approximately doubled in veterans with Agent Orange exposure compared with those with exposure (1918 of 38 121 [5.0%] vs 6886 of 278 230 [2.5%]; hazard ratio, 2.07 [95% CI, 1.96-2.18]) (Table 2). After adjusting for the competing risk of death, demographic variables, and medical and psychiatric conditions, veterans with Agent Orange exposure were still nearly twice as likely to develop dementia (hazard ratio, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.59-1.77]). Veterans with Agent Orange exposure also were a mean of 1.25 years younger at age of dementia diagnosis (mean [SD] age, 67.5 [7.0] vs 68.8 [8.0] years).

Figure. Cumulative Incidence of Dementia in Veterans With and Without Agent Orange Exposure.

Table 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Risk of Dementia by Agent Orange (n = 316 351).

| Group | Dementia incidence, No. (%) | Mean (SD) | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up y among people with dementia | Age at dementia onset, y | Unadjusted model | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | ||

| No Agent Orange (n = 278 230) | 6886 (2.5) | 4.3 (3.4) | 68.8 (8.0) | [1 Reference] | [1 Reference] | 1 [Reference] | [1 Reference] |

| Agent Orange (n = 38 121) | 1918 (5.0) | 4.6 (3.3) | 67.5 (7.0) | 2.07 (1.96-2.18) | 2.01 (1.90-2.11) | 1.88 (1.79-1.99) | 1.79 (1.69-1.88) |

| Fine-Gray model results | NA | NA | NA | 1.91 (1.82-2.01) | 1.86 (1.76-1.95) | 1.76 (1.66-1.85) | 1.68 (1.59-1.77) |

Abbrevation: NA, not applicable.

No Agent Orange exposure is the reference group; all P < .001.

Model 1: adjusted for demographic (race, sex, education, and income).

Model 2: adjusted for demographic and medical condition (diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, traumatic brain injury, and Parkinson disease).

Model 3: adjusted for demographic, medical conditions, and psychiatric disorders (mood disorder, anxiety, substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, tobacco use, and sleep disorder).

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample of more than 300 000 veterans of the Vietnam era, we found that exposure to Agent Orange was associated with approximately a 2-fold increased risk of being diagnosed with incident dementia and an earlier age of dementia diagnosis. These results were consistent after adjusting for comorbidities and other potential confounders.

There are several potential mechanisms by which Agent Orange could increase the risk of dementia. Dioxin is higher in the blood and adipose tissue of veterans from the Vietnam era who were exposed compared with control participants,9 and previous research suggests that it remains present in the body decades after exposure.10 Adipose’s integral role in dioxin storage and obesity-associated metabolic circuitry provides a mechanistically plausible pathway for the association between the presence of dioxin and cellular and molecular mechanisms of induced conditions, such as diabetes and Parkinson disease, which are 2 established dementia risk factors.11,12,13,14 Previous research examining dioxin’s neurotoxicity has found direct effects on the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, with corresponding alterations to various neuropeptides and hormones, especially in the dopaminergic system, and nervous tissue damage induced by oxidative stress, as well as indirect damage attributable to vascular impairment and blood-brain barrier dysfunction.13 Higher levels of dioxin have also been shown to be associated with worse verbal memory.15

Strengths of this study design include the large, nationally representative sample. In addition, the study required both patient and clinician reports of Agent Orange exposure.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include use of electronic health records for Agent Orange exposure and dementia diagnoses, which likely resulted in nondifferential misclassification that would tend to bias results toward the null. Additionally, our models may have adjusted for conditions on the causal pathway, which also would bias results toward the null. Our study sample was restricted to veterans who receive care within VHA, and results may not generalize to veterans who receive care outside VHA. We also did not have information about baseline cognitive scores. Finally, concerns about potential time-to-event bias were mitigated by studying the largely homogenous sample of veterans who served in Vietnam.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that veterans of the Vietnam era with presumptive Agent Orange exposure are nearly twice as likely as those without reported exposure to be diagnosed with dementia. Consequently, veterans with a history of Agent Orange exposure should be adequately screened and treated for dementia in later life. Additional research should continue to examine the potential mechanisms underlying the association between Agent Orange exposure and dementia.

eTable 1. Compare included and excluded sample, starting from 2% random sample of Vietnam-era veterans who received VA care from FY2002-FY2015 (total N=511,189).

eTable 2. Flow chart showing derivation of the analytic cohort after applying study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

References

- 1.Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice . National Academies of Sciences E and Medicine, Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Eleventh Biennial Update): Health and Medicine Division, Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 11 (2018). National Academies Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steenland K, Bertazzi P, Baccarelli A, Kogevinas M. Dioxin revisited: developments since the 1997 IARC classification of dioxin as a human carcinogen. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(13):1265-1268. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning . Projections of the prevalence and incidence of dementias including Alzheimer’s Disease for the total veteran, enrolled and patient populations age 65 and older. Published September 2013. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/Methodology_Paper_Projections_of_the_Prevalence_and_Incidence_of_Dementias_v5_FINAL.pdf

- 4.Barnes DE, Kaup A, Kirby KA, Byers AL, Diaz-Arrastia R, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology. 2014;83(4):312-319. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanner CM, Goldman SM, Ross GW, Grate SJ. The disease intersection of susceptibility and exposure: chemical exposures and neurodegenerative disease risk. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S213-S225. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan LL, Petersen NJ, Snow AL, et al. Prevalence of dementia among Veterans Affairs medical care system users. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(4):245-253. doi: 10.1159/000087345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.VA Dementia Registry Task Force . VA dementia registry methods report: summary data tables on demographics, service use and costs. Published 2006. Accessed April 24, 2019. http://vaww.arc.med.va.gov/gec/dementia/fy04/dementia2_reg_methods_report_2nov06.doc

- 9.Kahn PC, Gochfeld M, Nygren M, et al. Dioxins and dibenzofurans in blood and adipose tissue of Agent Orange–exposed Vietnam veterans and matched controls. JAMA. 1988;259(11):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03720110023029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalek JE, Pirkle JL, Needham LL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in Seveso adults and veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2002;12(1):44-53. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi S-W, Hong J-S, Ohrr H, Yi J-J. Agent Orange exposure and disease prevalence in Korean Vietnam veterans: the Korean Veterans Health Study. Environ Res. 2014;133:56-65. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J-Y, Lee Y. Response to letter to the editor: risk of incident dementia according to metabolic health and obesity status in late life: a population-based cohort study. J of Clin Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020;105(2):573-574. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urban P, Pelclová D, Lukás E, et al. Neurological and neurophysiological examinations on workers with chronic poisoning by 2,3,7,8-TCDD: follow-up 35 years after exposure. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(2):213-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64(2):277-281. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett DH, Morris RD, Akhtar FZ, Michalek JE. Serum dioxin and cognitive functioning among veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22(4):491-502. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(01)00051-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Compare included and excluded sample, starting from 2% random sample of Vietnam-era veterans who received VA care from FY2002-FY2015 (total N=511,189).

eTable 2. Flow chart showing derivation of the analytic cohort after applying study inclusion and exclusion criteria.