Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the association between disability, dementia, and depression and engagement in meaningful activities in community-dwelling older adults.

Participation and active engagement in meaningful activities is beneficial to the emotional and physical well-being of older adults.1,2 Meaningful activities are enjoyable activities that are associated with personal interests.2,3 Functional limitations, cognitive impairment, and depression may diminish the ability to participate and engage in meaningful activities and place older adults at higher risk of loss of identity and well-being.3 This study explored the association between disability, dementia, and depression and engagement in meaningful activities in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling adults 65 years and older.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) participants, who were 65 years or older from 2011 and 2015 (the years during which the meaningful activities questions were administered). This study was considered exempt by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco. This study was not considered human participants research because the data were deidentified and publicly available. The NHATS asks participants questions about their favorite activity (eg, “What is your favorite activity?”; “In the last month, did your health or functioning ever keep you from this activity?”). We defined meaningful activity as self-reported participation in a favorite activity that enhanced cognitive engagement (eg, reading), social connectedness (eg, socializing with others), or physical aptitude (eg, walking/jogging). Lack of meaningful activity included engaging in passive activities (eg, watching television2), the inability to do a favorite activity, and a lack of a favorite activity. Risk factors included disability (requires assistance with 1 or more basic activities of daily living), dementia (defined as probable dementia using a validated algorithm4), and depression (3 points or greater on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2).5 Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity and income. We used multinomial logistic regressions to determine adjusted probabilities of engagement in meaningful activities, passive activities, inability to do favorite activity, or lack of a favorite activity for participants with disability, dementia, depression, or any combination thereof. Next, we used a survey-weighted Poisson regression6 to estimate the risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs of engagement in meaningful activities while controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income. Analyses were performed in Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp) using NHATS-provided weights, and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

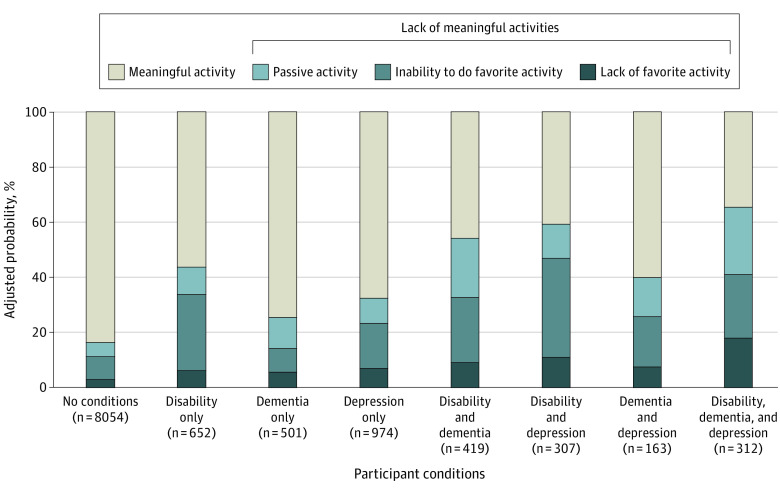

Of 11 382 participants, the mean (SD) age was 74.4 (7.2) years, 6571 (56%) were women, and 7655 (81%) were non-Hispanic White (Table). The top 3 favorite activities in the whole sample were walking/jogging (1537 [14%]), outdoor maintenance (1152 [10%]), and reading (979 [9%]). A total of 8054 participants with no conditions (84%; 95% CI, 83%-85%) were engaged in meaningful activities. In contrast, 652 participants with disability alone (56%; 95% CI, 52%-61%), 501 participants with dementia alone (74%; 95% CI, 70%-79%), 974 participants with depression alone (68%; 95% CI, 64%-71%), and 312 participants with all 3 conditions (35%; 95% CI, 27%-42%) were engaged in meaningful activities (Figure). In weighted, multivariable analyses that adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income, older adults with any condition or combinations of conditions were less likely to engage in meaningful activities compared with those with no conditions. Participants with disability alone or in combination were the least likely to engage in meaningful activities (disability alone: RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61-0.72; disability and dementia: RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56; disability and depression: RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.38-0.55; all 3 conditions: RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.27-0.45) (Table).

Table. Characteristics and Risk Ratios for Engagement in Meaningful Activities Among Various Disability, Dementia, and Depression Subgroups Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Income.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%)a | Adjusted risk ratio for engagement in meaningful activities (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.4 (7.2) | |

| 65-69 | 2403 (34) | 1 [Reference] |

| 70-74 | 2398 (24) | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) |

| 75-79 | 2246 (18) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) |

| 80-84 | 2092 (13) | 0.95 (0.92-0.98) |

| 85-89 | 1320 (8) | 0.91 (0.87-0.96) |

| ≥90 | 923 (4) | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 4811 (44) | 1 [Reference] |

| Women | 6571 (56) | 1.04 (1.02-1.07) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 7655 (81) | 1 [Reference] |

| African American | 2447 (8) | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) |

| Latino | 345 (4) | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) |

| Other | 697 (7) | 0.90 (0.85-0.96) |

| Income, $ | ||

| 0-12 000 | 2335 (16) | 1 [Reference] |

| 12 000-21 144 | 2405 (18) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

| 21 444-35 000 | 2249 (19) | 1.07 (1.03-1.11) |

| 35 001-60 000 | 2276 (22) | 1.07 (1.03-1.11) |

| ≥60 001 | 2293 (26) | 1.09 (1.06-1.13) |

| Subgroups | ||

| No conditions | 8054 (76) | 1 [Reference] |

| Disability only | 652 (5) | 0.85 (0.79-0.91) |

| Dementia only | 501 (3) | 0.67 (0.62-0.72) |

| Depression only | 974 (8) | 0.80 (0.76-0.85) |

| Disability and dementia | 419 (2) | 0.46 (0.39-0.55) |

| Disability and depression | 307 (2) | 0.69 (0.59-0.80) |

| Dementia and depression | 163 (1) | 0.49 (0.42-0.57) |

| Disability, dementia, and depression | 312 (2) | 0.36 (0.28-0.45) |

Based on weighted population estimates.

Risk ratios are a better estimate of relative risk than odds ratios when outcomes are common; therefore, we estimated adjusted risk ratios using a survey-weighted Poisson regression with a robust error variance procedure known as sandwich estimation term, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income.

Figure. Adjusted Probabilities for Meaningful Activities for National Health and Aging Trends Study Participants by Subgroup and Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Income.

Discussion

In this nationally representative survey, more than half of older adults with either disability, dementia, or depression were engaged in meaningful activities, although these rates were lower compared with older adults without these conditions. Our findings suggest that engagement in meaningful activities is possible despite the presence of disability, dementia, and depression. Notably, the top 2 favorite activities of participants were physical, which may explain why disability commonly precluded engagement in meaningful activities. We recognize the study limitations that some may disagree with the categorization of certain passive activities as nonmeaningful and that activities were assessed by self-report. Nonetheless, we believe engagement in meaningful activities is central to one’s identity and well-being.

References

- 1.Irving J, Davis S, Collier A. Aging with purpose: systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2017;85(4):403-437. doi: 10.1177/0091415017702908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley JE, Philpot CD, Gill D, Berg-Weger M. Meaningful activities in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(2):79-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz P. Function, disability, and psychological well-being. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;25:41-62. doi: 10.1159/000079057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Accessed May 25, 2017. https://www.nhats.org/scripts/documents/DementiaTechnicalPaperJuly_2_4_2013_10_23_15.pdf

- 5.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study user guide: rounds 1-8 final release. Accessed August 29, 2020. http://www.nhats.org

- 6.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]