CONSPECTUS:

α-Synuclein (α-syn) is a key protein in the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. In a disease state, α-syn accumulates as insoluble amyloid fibrils enriched in β-sheet structure. However, in its functional state, α-syn adopts an amphipathic helix upon membrane association and plays a role in synaptic vesicle docking, fusion, and clustering. In this Account, we describe our contributions made in the past decade toward developing a molecular understanding of α-syn membrane interactions, which are crucial for function and have pathological implications. Three topics are covered: α-syn membrane binding probed by neutron reflectometry (NR), the effects of membrane on α-syn amyloid formation, and interactions of α-syn with cellular membranes.

NR offers a unique perspective by providing direct measurements of protein penetration depth. By the use of segmentally deuterated α-syn generated through native chemical ligation, the spatial resolution of specific membrane-bound polypeptide regions was determined by NR. Additionally, we used NR to characterize the membrane-bound complex of α-syn and glucocerebrosidase, a lysosomal hydrolase whose mutations are a common genetic risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. Although phosphatidylcholine (PC) is the most abundant lipid species in mammalian cells, interactions of PC with α-syn have been largely ignored because they are substantially weaker compared with the electrostatically driven binding of negatively charged lipids. We discovered that α-syn tubulates zwitterionic PC membranes, which is likely related to its involvement in synaptic vesicle fusion by stabilization of membrane curvature. Interestingly, PC lipid tubules inhibit amyloid formation, in contrast to anionic phosphatidylglycerol lipid tubules, which stimulate protein aggregation. We also found that membrane fluidity influences the propensity of α-synuclein amyloid formation. Most recently, we obtained direct evidence of binding of α-syn to exocytic sites on intact cellular membranes using a method called cellular unroofing. This method provides direct access to the cytosolic plasma membrane. Importantly, measurements of fluorescence lifetime distributions revealed that α-syn is more conformationally dynamic at the membrane interface than previously appreciated. This exquisite responsiveness to specific lipid composition and membrane topology is important for both its physiological and pathological functions. Collectively, our work has provided insights into the effects of the chemical nature of phospholipid headgroups on the interplay among membrane remodeling, protein structure, and α-syn amyloid formation.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

α-Synuclein (α-syn), a neuronal protein enriched in presynaptic nerve terminals, is linked to Parkinson’s disease (PD).4 Intracellular accumulations of α-syn amyloid fibrils constitute the major component of Lewy bodies, which are pathological hallmarks of PD.5 There is a direct connection between gene duplication and triplication as well as missense mutations of the SNCA gene, which encodes for α-syn, causing early-onset PD.6

On a cellular level, overexpression of α-syn can result in abnormal disruption of organelles including Golgi,7 mitochondria,8 and lysosomes,9 implicating α-syn in membrane perturbations. Importantly, the putative physiological function of α-syn is thought to be related to its ability to associate with synaptic vesicles, playing a role in neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity.10 Therefore, a fundamental understanding of α-syn and lipid interactions are of both biological and pathological importance.

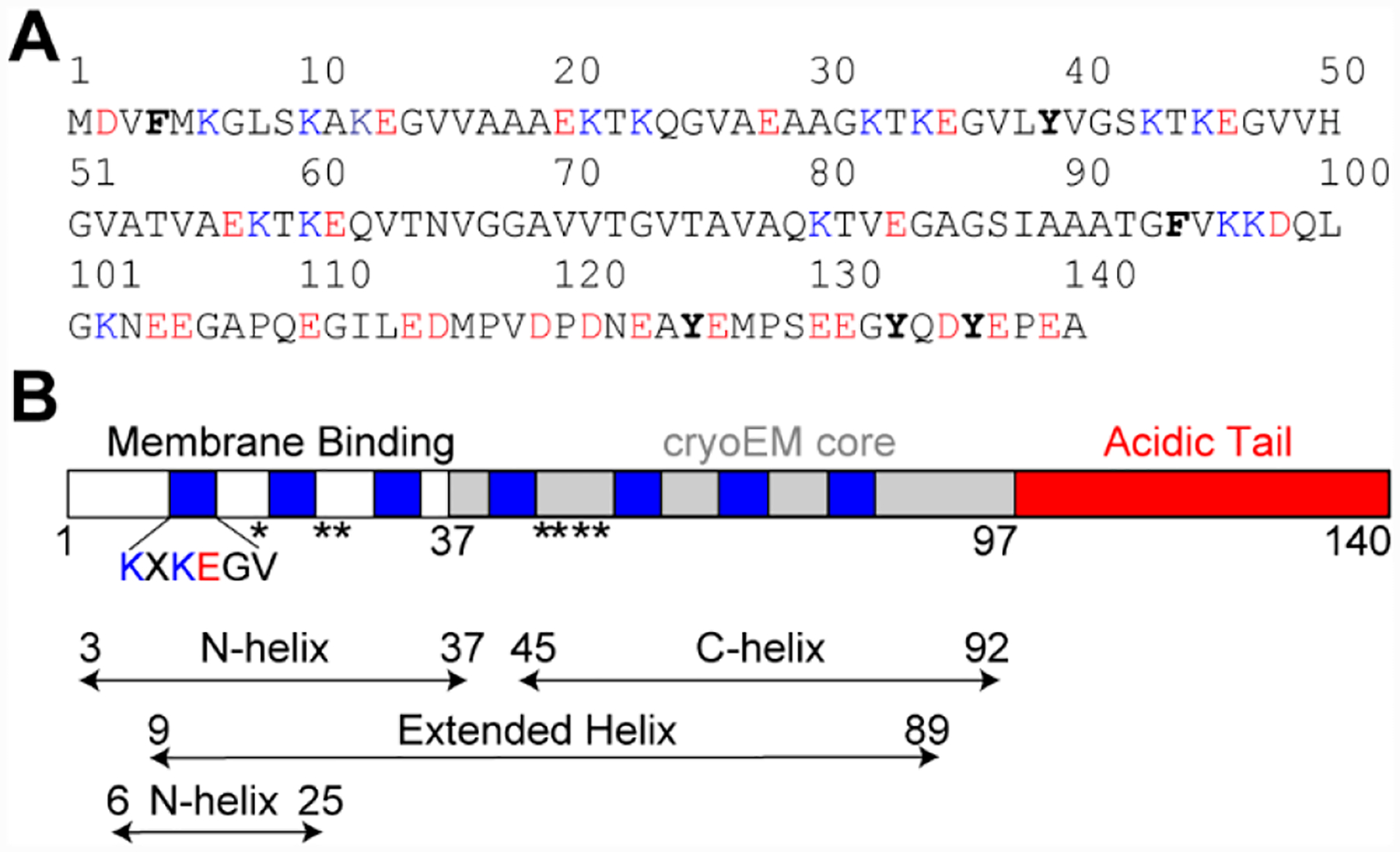

α-Syn is 140 amino acids in length and primarily exists as an intrinsically disordered protein in the cytosol.11,12 The first 89 residues contain seven imperfect 11-residue amphipathic repeats (XKXKEGVXXXX) (Figure 1A) that form an amphipathic helix upon lipid binding in vitro.13 Depending on the curvature of the membrane, this region can either form a bent helix, characterized by two antiparallel α-helices (residues 3–37 and 45–92) connected by a linker,14 or exist in a dynamic equilibrium between a single extended helix (residues 9–89)15 and a short N-terminal helix (residues 6–25) with a weakly associated unstructured portion (residues 26–98)16 (Figure 1B). It remains to be determined if these α-syn conformers (co)exist on cellular membranes.

Figure 1.

Structural characterization of membrane-bound α-syn. (A) Amino acid sequence of α-syn. Basic and acidic residues are colored blue and red, respectively. Aromatic residues are shown in bold. (B) Schematic representation of α-syn shown with amphipathic repeats (blue), cryoEM core (gray), and acidic tail (red). PD-related mutations (A18T, A29S, A30P, E46K, H50Q, G51D, A53E, and A53T) are denoted with asterisks. Helical regions of α-syn bound to micelles (residues 3–37 and 45–92)14 and vesicles (residues 9–8915 or 6–2516) are indicated.

The eight currently known missense PD mutations of α-syn (A18T, A29S, A30P, E46K, H50Q, G51D, A53T, and A53E) are located within this N-terminal region with varying effects on lipid binding affinity (Figure 1B).17,18 Notably, the subsequent polypeptide region (residues 37–97) folds into a β-sheet-rich amyloid fibril structure associated with the disease state.19 Finally, the remaining C-terminal residues remain largely unstructured in both membrane-bound14–16 and aggregated states.19

Many bilayer properties, including phospholipid headgroup charge, exposure of hydrocarbon acyl chains (packing defects), and membrane fluidity and curvature, modulate α-syn binding.20 In vitro, α-syn has a strong preference for highly curved negatively charged vesicles due to the preponderance of packing defects and favorable electrostatic interactions with numerous positively charged lysine residues in the N-terminus.21–24 In cellular membranes, zwitterionic lipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) are the most abundant; however, anionic lipids are enriched in different cellular compartments.25 For example, lipidomic analysis suggests that anionic phosphatidylserine (12%) and phosphatidylinositol (1.8%) are present in synaptic vesicles with PE (43%), PC (36%), and sphingomyelin (SM) (7%) constituting the majority.26 Another noted component of synaptic vesicles is cholesterol (Chol) (40 mol %).

PS, PI, and phosphatidic acid (PA) are also found in the inner plasma membrane.27 Moreover, it is thought that the local accumulation of PA at exocytic sites may play a regulatory role.28 It is also relevant to point out that the concentration of PA increases with age, as PD is an age-related disease.29,30 Furthermore, because membranes serve as a two-dimensional folding template, different lipids can also influence the aggregation propensity of α-syn, which is related to pathogenesis. For example, both PA and PS have been shown to stimulate α-syn amyloid formation in vitro.25 This intimate relationship between lipids and α-syn is further substantiated in recent studies showing that Lewy bodies are membrane-rich inclusions.31 Thus, the nature of the lipid environment and how it influences α-syn conformation are important for both function and pathology.

Here we give an account of our research efforts to elucidate molecular events in α-syn amyloid pathology by characterizing α-syn conformational changes influenced by lipid membranes. There are three main sections: neutron reflectometry (NR) studies of α-syn, effects of lipids on α-syn amyloid formation, and interactions of α-syn with cellular membranes. First, we describe our NR results on α-syn penetration depth within a bilayer, region-specific membrane interactions, and characterization of the membrane-bound complex of α-syn and glucocerebrosidase (GCase), a lysosomal hydrolase whose mutations cause Gaucher disease (GD) and are a common genetic risk factor for PD.32 Second, we discuss the interplay between α-syn amyloid formation and membrane structure, where membrane tubulation has distinct effects on the aggregation kinetics depending on the specific lipid composition. Lastly, we highlight our latest work to interrogate native α-syn–lipid interactions through the techniques of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) and cellular unroofing, which uncovers an intact basal membrane that recapitulates the topology and complexity of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane.

2. NEUTRON REFLECTOMETRY STUDIES OF α-SYNUCLEIN

2.1. Depth of α-Syn in a Bilayer

While much is known about α-syn conformational changes upon membrane binding (Figure 1B),13–16 the reciprocal effect of α-syn on the molecular structure of phospholipid bilayers has been less well characterized. To fill this gap and to gain information from the perspective of the membrane, we employed NR on a surface-stabilized sparsely tethered bilayer lipid membrane (stBLM).33 NR is a scattering technique that provides structural information along the direction normal to the bilayer plane with nanometer resolution. Unlike most techniques, it can simultaneously report on the membrane-bound protein and bilayer structural properties such as protein insertion into the bilayer and its extension into the surrounding bulk solvent as well as changes in membrane thickness.34

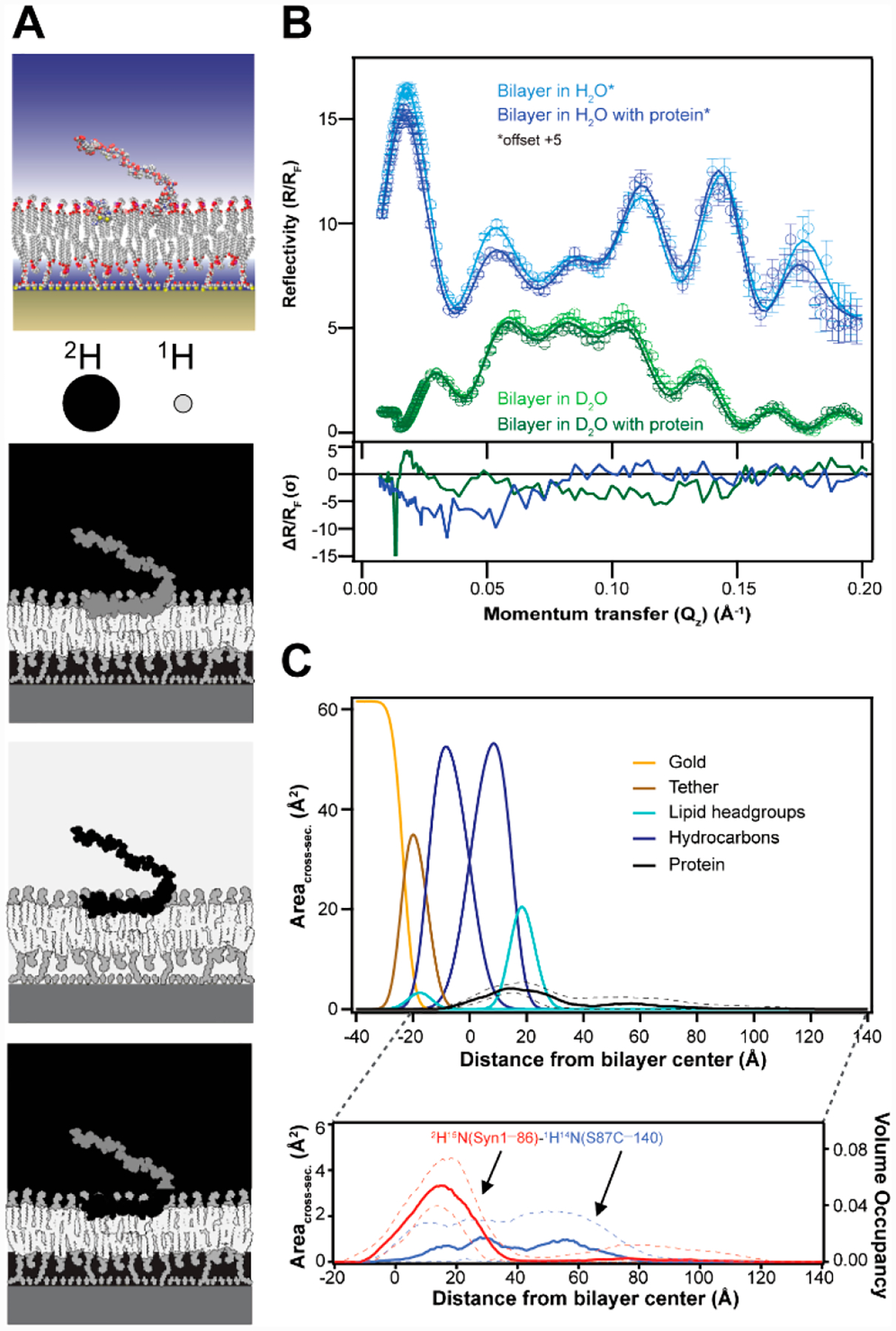

NR is particularly suited for biological applications because neutrons have highly disparate scattering length densities for two stable isotopes of hydrogen (protium and deuterium), which are schematically depicted in Figure 2A.33 Favorable scattering length density contrast between a molecule of interest and its surroundings can be created by choosing which part of a surface architecture to isotopically label. For example, contrast can be gained in solution by using D2O and protiated α-syn (Figure 2A).35 Analogously, the position of a uniformly deuterated α-syn is readily distinguished in a protiated lipid environment.36

Figure 2.

Region-specific α-syn–membrane interactions probed by NR. (A) Schematic representation of α-syn bound to a stBLM. Shown are three examples of isotopic contrasts, where the protein is either protiated, deuterated, or segmentally deuterated. (B) (top) Fresnel-normalized neutron reflectivity (R/RF) for an equimolar POPC/POPA stBLM in the absence or presence of ligated α-syn with N-terminal deuteration (2 μM) in H2O (blue) or D2O (green) buffer (pH 7.0). Reflectivity curves in H2O buffer have been offset by 5 units for presentation clarity. Error bars represent 68% confidence intervals for the measured reflectivity based on Poisson statistics. (bottom) Differences between reflectivity curves (ΔR/RF) plotted in units normalized by the experimental error (one standard deviation, σ). (C) Simplified molecular distributions for each modeled interfacial component of the POPC/POPA stBLM and ligated N-terminal deuterated α-syn (2H15N(Syn1–86)–1H14N(S87C–140). (top) Median protein envelope (black) shown with a 68% confidence interval (dashed lines). From left to right: gold (yellow), tether (brown), first-layer lipid headgroups (cyan), first-layer hydrocarbons (blue), second-layer hydrocarbons (blue), and second-layer lipid headgroups (cyan). Data for the Si substrate and the SiOx, Cr, and Au layer have been partially omitted for simplicity. (bottom) Deconvoluted individual distributions for the deuterated residues 1–86 and protiated residues 87–140 are shown in red and blue, respectively. Volume occupancy is indicated on the right axis.

In this approach, α-syn associates peripherally to the stBLM composed of equimolar PC and PA. We chose PA because α-syn binds strongly to this biologically relevant anionic lipid, ensuring sufficient surface coverage. A penetration depth of ~11 Å from the bilayer center was determined. Even though there is a preference for α-syn binding to PA, a similar penetration depth was obtained with PS-containing stBLM, suggesting that this is a general feature for the α-syn membrane-bound state.36 This finding was corroborated by fluorescence quenching experiments using brominated phospholipids in unilamellar vesicles composed of either PC/PA or PC/PS, where average Trp insertion depths of 9–10 Å were obtained at three different sites (W4, W39, and W94).35,36

2.2. Segmental Deuteration Creates Region-Specific Neutron Scattering Contrast

As described above, NR provides global information on protein–membrane interactions, where isotopic labeling of the protein of interest can be used to enhance the contrast against its surrounding environment. However, uniform protein deuteration does not provide region-specific information within a protein distribution by NR. To distinguish specific polypeptide regions within α-syn, we coupled native chemical ligation with NR. Since the membrane binding region of α-syn encompasses the first 100 residues, we generated an N-terminal (1–86) and C-terminal (87–140) α-syn variant to gain direct information on how the N-terminus interacts with the lipid bilayer.1 Ligation of the uniformly deuterated portion (1–86) to the respective protiated segment (87–140) allowed for scattering contrast within full-length α-syn (Figure 2A, bottom panel).

Representative reflectivity curves (ΔR/RF) of equimolar PC/PA stBLM before and after addition of ligated N-terminal deuterated α-syn are shown with two buffer contrasts in Figure 2B (top panel).1 Significant differences in reflectivity are observed upon the addition of ligated N-terminal deuterated α-syn (Figure 2B, bottom panel). A model fit to the reflectivity curve yields volume occupancy profiles of the protein and bilayer components that describe what fraction of the volume is occupied by each component along the direction normal to the membrane (Figure 2C). Consistent with our prior data,35,36 the majority of the protein localizes peripherally, with some penetration into the hydrocarbon region (black curve). The protein distribution can be further separated into the deuterated portion (1–86, red curve) and protiated portion (87–140, blue curve). The membrane-bound N-terminal portion displays a relatively narrow distribution with a maximum around the hydrocarbon–headgroup interface, whereas the density distribution of the C-terminus is diffuse, extending from the hydrocarbons into the bulk solvent. This methodology of coupling segmental deuteration with NR is broadly applicable for other protein–membrane studies.

2.3. α-Syn–GCase Interactions on Membranes

Mutations in the gene encoding for GCase (GBA1) cause the lysosomal storage disorder known as Gaucher disease and are recognized as the most common risk factor for PD development,32 suggesting a potential link between these two diseases.37 GCase is a lysosomal enzyme that hydrolyzes the glycolipid glucosylceramide into glucose and ceramide.38 Despite the strong clinical connection between GD and PD, mechanistic insights remain elusive and are a topic of wide interest. Different models have been proposed for the observed association and used to explain the apparent reciprocal relationship between GCase levels/activity and α-syn (for reviews, see refs 37 and 39–42).

In our own work, we discovered that a physical interaction existed between GCase and α-syn under lysosomal conditions as a possible molecular connection.43 Since membranes are pertinent for both GCase activity44 and α-syn conformation, we turned to NR to gain structural information on the membrane-bound α-syn–GCase complex.45 Again, we leveraged the neutron scattering contrast between protons and deuterons to distinguish the proteins in the complex. Individual contributions from protiated GCase and deuterated α-syn were extracted from the membrane-bound complex.

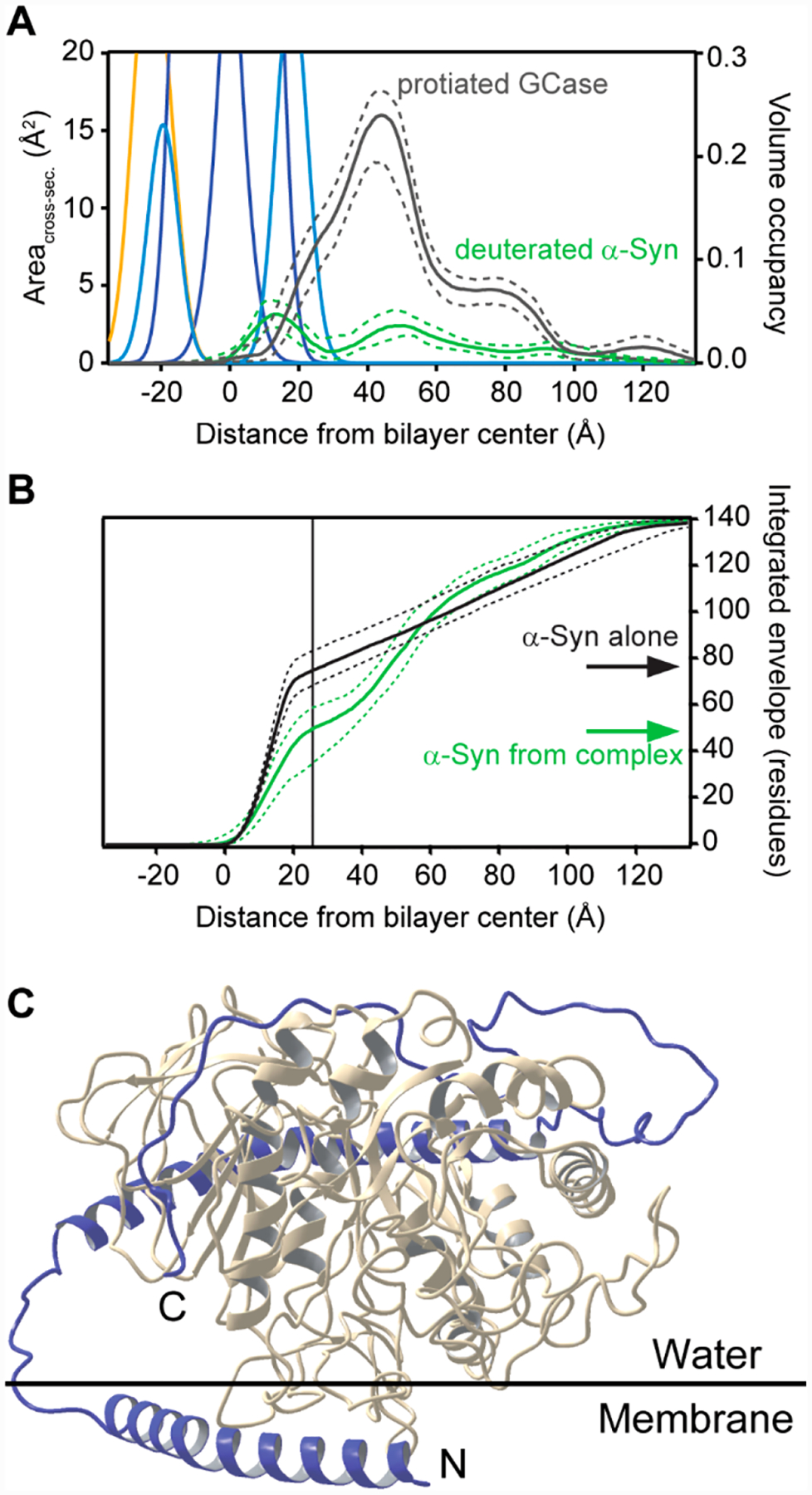

The extracted GCase profile shows that the majority of the density is peripheral to the membrane, with a portion penetrating into the hydrocarbon chains of the equimolar PC/PS stBLM (Figure 3A, gray curve).45 We used a PC/PS stBLM because GCase activity and α-syn–GCase binding on PC/PS vesicles had been previously characterized.44 The extracted profile of α-syn in the complex (Figure 3B, green curve) is different from that of α-syn alone (Figure 3B, black curve). Integration of the α-syn density profile revealed that fewer residues of α-syn are located in the bilayer (~48 vs 73 residues) in the presence of GCase, suggesting that roughly half of the α-helical structure of α-syn lies above the plane of the bilayer. To visualize what this complex may look like, a molecular model was constructed (Figure 3C). Taken together with other biophysical data,45 these results show that association of α-syn alters the GCase conformation, moving GCase away from the membrane surface, which results in perturbation of the active site and enzyme inhibition. NR revealed structural features not observable by other techniques, offering molecular insights into GCase inhibition by α-syn.

Figure 3.

Structural characterization of membrane-bound GCase and α-syn by NR. (A) Simplified molecular distributions for each component of the POPC/POPS stBLM, the median protein envelope for protiated GCase (gray), and deuterated α-syn (green) obtained from the fit of reflectivity data to a spline model. Dashed lines indicate 68% confidence intervals. Volume occupancy is indicated on the right axis. (B) Integrated profiles for deuterated α-syn alone (black) and deuterated α-syn extracted from the α-syn–GCase complex (green). The integral is normalized to the total number of residues (140). Dashed lines represent 68% confidence intervals. (C) Model structure of the membrane-bound α-syn (blue)–GCase (gray) complex. N- and C-termini of α-syn are labeled.

3. INTERPLAY OF α-SYN AMYLOID FORMATION AND MEMBRANE STRUCTURE

3.1. Effect of Membrane Remodeling on α-Syn Aggregation

Binding of α-syn to phospholipid bilayers can induce structural transformation of the membrane (i.e., remodeling) including tubulation2,46 and vesiculation.47 The ability of α-syn to tubulate membranes was first reported for anionic 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac)-glycerol (POPG) (Figure 4A).46 Since then, this remodeling behavior has been documented for other anionic lipids including POPA and POPS.48

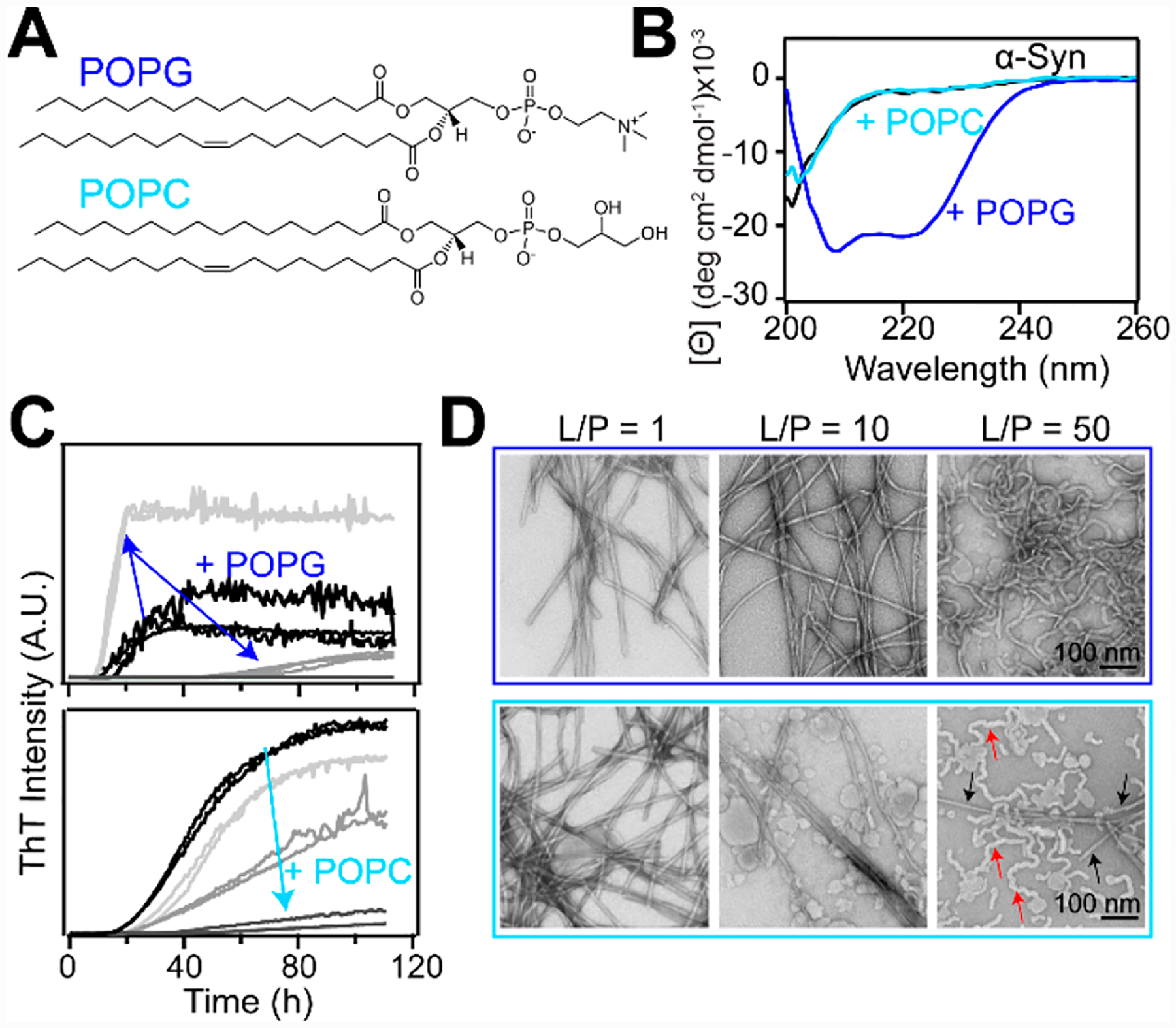

Figure 4.

α-Syn amyloid formation in the presence of lipid membranes. (A) Chemical structures of POPG and POPC. (B) CD spectra of α-syn alone (black) and in the presence of either POPG (blue) or POPC (cyan) vesicles (L/P = 20). (C) Aggregation kinetics of α-syn (70 μM) monitored by ThT fluorescence (10 μM) in solution (black) with increasing POPC or POPG vesicles (light to dark gray, L/P = 1, 10, and 50, in 20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7) at 37 °C with shaking. (D) Representative TEM images of products at the end of aggregation reactions in the presence of POPG (top) and POPC (bottom). In the bottom right image, red and black arrows indicate POPC lipid tubules and α-syn fibrils, respectively. Scale bars are 100 nm.

In our work, we focused on studies to investigate the effect of membrane tubulation on α-syn aggregation.48 POPG tubes are stabilized by α-helical α-syn as assessed by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, a probe of secondary structure (Figure 4B, blue curve). They range from ~7–30 nm in diameter depending on the lipid-to-protein (L/P) ratio.48 We observed that the α-syn aggregation kinetics is accelerated under conditions where POPG micellar tubes (7 nm) are formed (Figure 4C, top panel, L/P = 1), as monitored by thioflavin-T (ThT), an extrinsic fluorophore that increases in fluorescence intensity upon binding to amyloid fibrils.49 In contrast, at a higher L/P of 50, where wider bilayer tubes (~30 nm) are formed, the ThT signal is reduced, suggesting inhibition of amyloid formation, which was corroborated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 4D, top panel). It is evident that rodlike fibrils are formed at L/P = 1 and 10 but that the wide tubes remain at L/P = 50. Consistently, CD data also demonstrated that α-syn developed β-sheet structure at L/P = 1 but remained α-helical at L/P = 50.48 This observation that POPG micellar tubes induced by α-syn can stimulate amyloid formation has pathological implications, as amyloids accumulate in PD. It is also evident that the relative protein-to-lipid levels are important, as protein aggregation can be suppressed with increased lipid concentrations.

While these data are compelling, anionic lipids are less abundant in biological membranes compared with zwitterionic PC phospholipids.50,51 Thus, we were motivated to investigate the effects of PC lipids, which are often underappreciated because the interactions of α-syn with PC lipids are substantially weaker compared with electrostatically driven binding to negatively charged membranes.20

In contrast to POPG, no detectable secondary structural changes were detected by CD spectroscopy for α-syn in the presence of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) vesicles, indicating that the protein is disordered in solution and does not interact with lipids (Figure 4B, cyan curve).2 To our surprise, tubulation of POPC vesicles was revealed by TEM and strongly suggested that the protein indeed interacted with POPC despite the lack of α-helix formation.2 The POPC tubules induced by α-syn are wider (~20 nm diameter) than the micellar tubes observed in the presence of POPG vesicles.

Using five single-tryptophan variants of α-syn and time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy measurements, we confirmed that α-syn was bound very weakly (partition constant Kp ≈ 300 M−1) with no site specificity.2 This finding of an unstructured α-syn generating membrane curvature challenges the prevailing amphipathic helix insertion model that explains POPG micellar tubule formation.52 Interestingly, unlike POPG micellar tubes, POPC tubulation suppressed α-syn amyloid formation under all conditions examined (Figure 4C and Figure 4D, bottom panel).2 At high L/P, POPC tubules are prevalent (Figure 4D, bottom panel, red arrows), implying that there is competition for the available pool of free α-syn to either stabilize POPC tubules or assemble into amyloid fibrils.

Taken together, these results indicate that monomeric α-syn can alter the membrane morphology in a variety of ways depending on the specific lipid composition and the lipid-to-protein ratio. Our work offers new insights into possible biological consequences for α-syn-induced membrane remodeling. The functional relevance is supported by the observed enhanced levels of several membrane curvature sensing/generating proteins (BAR domains) in mice with all three α-, β-, and γ-syn genes knocked out, suggesting compensation for the loss of function from α-syn deficiency.53 On the other hand, pathological consequences can result from a lipid metabolism imbalance (e.g., age), where local lipid compositions are changed such that aberrant membrane deformation of organelles occurs or amyloid formation is facilitated.

3.2. Effect of Membrane Fluidity on α-Syn Aggregation

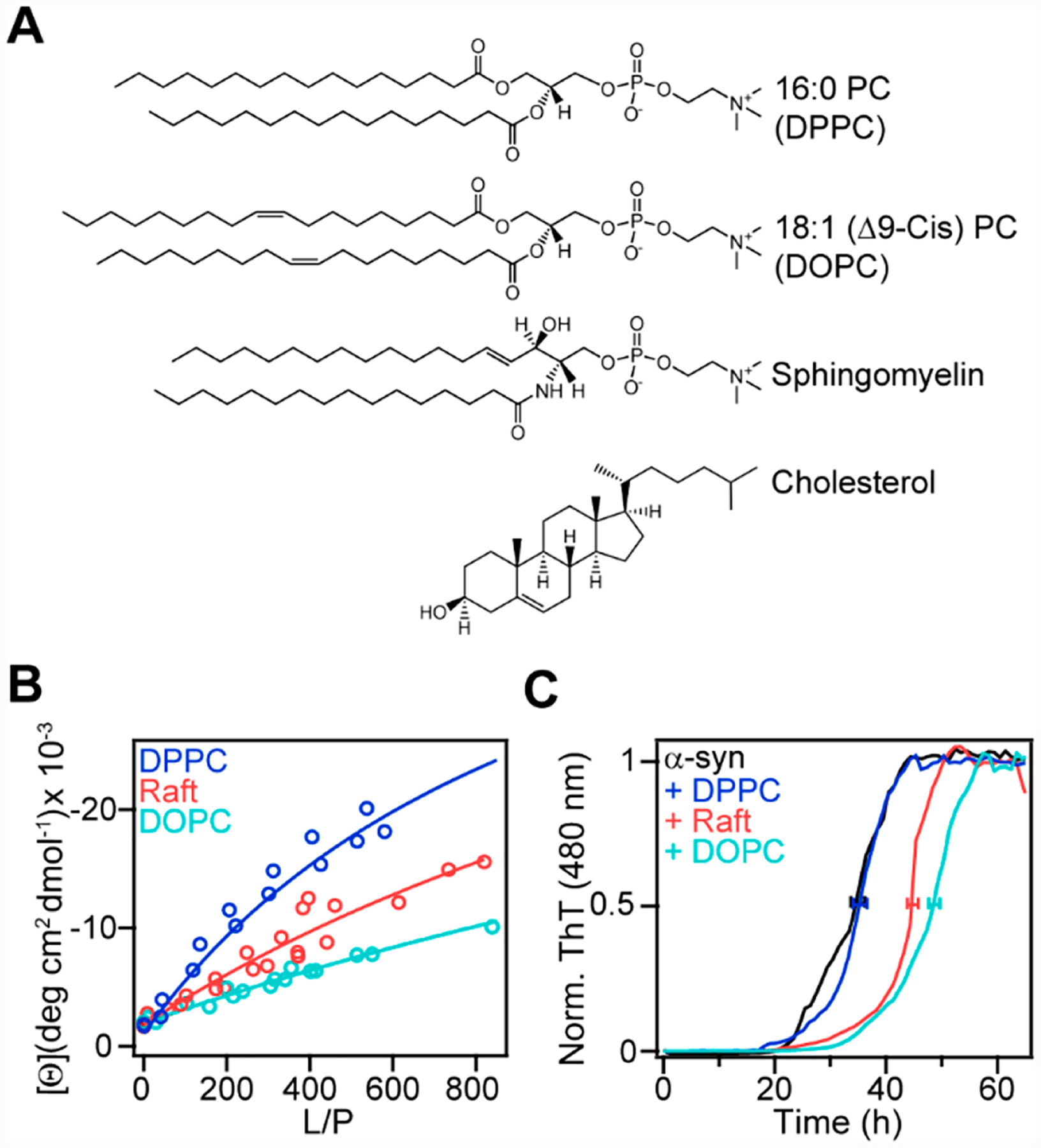

Next, we examined the effect of membrane fluidity on α-syn binding and aggregation. We were motivated by three observations. First, α-syn exhibits an unusual preference for saturated PC lipids in a gel state.23 Second, the close packing of lipids that occurs in the gel phase mimics the lipid ordering found in cellular lipid rafts, which are of physiological importance.54 Third, membrane fluidity has been shown to influence α-syn aggregation for anionic phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylserine.55

Using CD spectroscopy, we compared the formation of α-helical structure in α-syn induced by gel-phase 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) vesicles with vesicles composed of a lipid raft mixture (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), SM, and Chol) and fluid-phase (DOPC) vesicles (Figure 5A).56 These titration curves clearly show that there is a reciprocal relationship between α-helicity and membrane fluidity, where more folding was induced by ordered lipids (Figure 5B).56 Interestingly, the aggregation kinetics also indicated a similar correlation, with both DOPC and DOPC/SM/Chol exerting an inhibitory effect, whereas the ordered DPPC vesicles had minimal impact (Figure 5C). This observation is counterintuitive, as one may have expected that protein aggregation on fluid membranes is more favorable because of increased mobility and intermolecular encounters on the vesicle. However, stronger binding of α-syn to ordered membranes likely leads to more bound proteins on the surface, which could then serve as interaction sites for free monomers to initiate aggregation. These results implicate that lipid rafts and other ordered lipid domains found in cellular membranes may play a greater role in initiating and propagating fibril formation compared with fluid membranes.

Figure 5.

Effect of PC membrane fluidity on α-syn conformation and amyloid formation. (A) Chemical structures of DPPC, DOPC, SM, and Chol. (B) Binding curves generated from mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222 nm) for α-syn (5 μM) as a function of increasing DPPC (blue), DOPC/SM/Chol (2:2:1, red), and DOPC (teal) vesicles at 20 °C. The partition constants (Kp) extracted from fits to a two-state equilibrium (solid lines) were 700 ± 200, 300 ± 100, and 100 ± 100 M−1 for DPPC, DOPC/SM/Chol, and DOPC, respectively. (C) Aggregation kinetics of α-syn (50 μM) monitored by ThT fluorescence (10 μM) in the absence (black) or presence of DPPC (blue), DOPC/SM/Chol (pink), or DOPC (teal) vesicles (L/P = 10, in 20 mM MOPS, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7) at 37 °C with shaking. Normalized and averaged ThT data are shown (n ≥ 2). Error bars denote the standard deviation of the mean time to reach half intensity (≤2 h).

4. α-SYN LOCALIZATION AND SITE-SPECIFIC INTERACTIONS AT THE CYTOPLASMIC MEMBRANE

Substantial knowledge about α-syn–lipid interactions has been gained using simplified membrane mimetics such as micelles and vesicles; however, we lack molecular insights on how α-syn binding and conformation responds to the heterogeneous lipid and protein composition of a cellular membrane with topological and mobility differences (i.e., curvature and fluidity). To address this deficiency, we coupled cellular unroofing, site-specific labeling of an environmentally sensitive fluorophore, 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl (NBD), and FLIM to interrogate the membrane-bound conformational state of α-syn with spatial resolution on the cytoplasmic plasma membrane.3

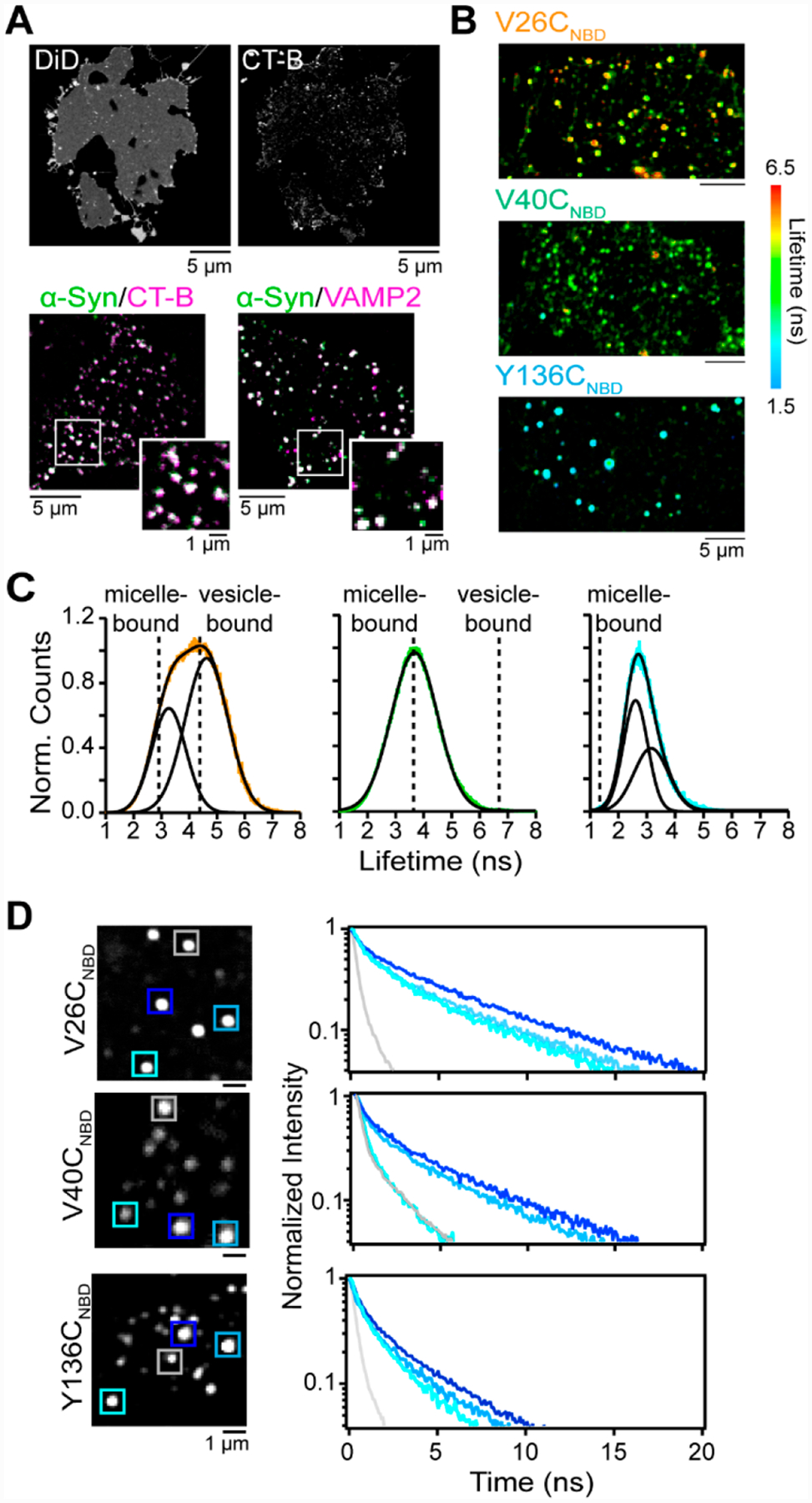

Cellular unroofing permits direct access to the cytoplasmic plasma membrane; through the application of brief ultrasonic pulses, the soluble cytoplasmic components are released, leaving behind an intact basal membrane.57 Representative confocal fluorescence images of unroofed cells are shown in Figure 6A. Nativelike properties of the membrane, composed of disordered and ordered lipids, were visualized by staining with a lipophilic DiD fluorophore and a fluorophore-labeled cholera toxin B subunit (CT-B), that binds to GM1, a ganglioside enriched in lipid rafts,58 respectively (Figure 6A, top panel). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments were performed to ascertain lipid immobilization, indicative of liquid-ordered lipid domains.3

Figure 6.

Probing α-syn-lipid interactions on unroofed cells. (A) (top) Confocal fluorescence images of DiD- and CT-B-stained unroofed SKMEL-28 cells. (bottom) Composite confocal fluorescence images of V26CNBD-α-syn (green) with CT-B (magenta) and VAMP2 (magenta) Colocalized areas appear white. Expanded views are also shown. Scale bars are as indicated. (B) FLIM images of V26CNBD, V40CNBD, and Y136CNBD α-syn on unroofed SK-MEL-28 cells. The color scale spans a lifetime of 6.5 to 1.5 ns. (C) Fluorescence lifetime distributions of V26CNBD (orange), V40CNBD (green), and Y136CNBD (cyan). Solid black lines represent Gaussian fits with χ2 values of 0.26 (V26CNBD), 0.17 (V40CNBD), and 0.24 (Y136CNBD). Dashed lines indicate τavg values obtained in the presence of LPC micelles and DOPC/GM1 vesicles. (D) NBD fluorescence decay kinetics measured from individual puncta for V26CNBD (top), V40CNBD (middle), and Y136CNBD (bottom). Locations are indicated by colored boxes (left panels).

To determine α-syn localization, we derivatized three Cys variants (V26C, V40C, and Y136C) with an environmentally sensitive fluorophore, NBD.59 This strategy gives us a direct membrane interaction probe because NBD is weakly emissive in aqueous solution but upon membrane insertion gives a robust, spectrally distinct response (emission wavelength, quantum yield, and lifetime).

Surprisingly, α-syn localized to unroofed cells in a punctate distribution, similar to those displayed by CT-B, representing GM1-rich lipid domains (Figure 6A, bottom panel).3 These areas correspond to exocytic sites where SNARE proteins such as VAMP2 are found (Figure 6A, bottom panel).3 Although α-syn has been proposed to bind to VAMP2 and aid in synaptic vesicle fusion,60–62 their spatial colocalization on the cytoplasmic membrane had not been seen previously. Additional colocalization was also seen with syntaxin-1, another SNARE protein, and Rab3a, a regulatory protein of exocytosis. The recruitment of α-syn to these regions is likely driven by membrane curvature and native protein–lipid complexes that are present only on intact plasma membranes.

To gain information about the conformational heterogeneity of membrane-bound α-syn at the three NBD-labeled sites, a time-resolved image acquisition method, FLIM, was utilized to provide fluorescence lifetime distributions. FLIM images of V26CNBD, V40CNBD, and Y136CNBD display punctate patterns on unroofed cells, similar to those seen with confocal fluorescence microscopy. Here, rather than an intensity-based signal, each spot now shows a range of colors, indicating a wide range of measured NBD lifetimes per pixel (Figure 6B).3 All three sites exhibit longer lifetimes than free protein in solution, confirming that each residue is embedded in the hydrophobic lipid environment.

The breadth and average lifetime (τavg) of the distributions trend with the relative position, where the broadest distribution and longest τavg are seen for the N-terminal site, V26CNBD (Figure 6C, right panel). It is well-described by two Gaussian functions with peak maxima centered at 3.2 and 4.6 ns, which are distinct from those measured in micelles or vesicles, suggesting different conformers from the bent and extended helix conformations (Figure 1B). Our results uncover that the presumed well-folded N-terminus experiences the most heterogeneous lipid environments and is conformationally dynamic on unroofed cells, which is not well explained by the available structural models derived from purely lipid-containing membrane mimetics.14–16

In contrast, the lifetime distribution of V40CNBD fit well to a single Gaussian function whose peak maximum is centered at the micelle-bound τavg value (Figure 6C, middle panel). In addition, the lifetime distribution of Y136CNBD indicates that the C-terminus is in a more hydrophobic environment that is not recapitulated by either micelle or vesicle models (Figure 6C, right panel). These results indicate that the C-terminus interacts with unroofed cells, suggesting that it could mediate protein–lipid interactions at the plasma membrane.

It is notable that while V26CNBD exhibits the greatest conformational heterogeneity, as evidenced by its broad lifetime distribution, both V40CNBD and Y136CNBD also adopt various conformers (Figure 6D). All three sites experience a multitude of local environments, including being exposed to the aqueous and lipid/protein surroundings, as indicated by the presence of both short and long lifetimes at individual puncta. Collectively, our results show that unroofed cells represent a biologically relevant, valuable membrane platform for protein–lipid interaction studies. Importantly, we provide evidence that α-syn binds to exocytic sites, where different regions of the protein sample a diverse membrane environment. This observed conformational plasticity aids α-syn in carrying out its biological function at the plasma membrane.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the last 10 years, we have applied a myriad of biophysical and spectroscopic techniques toward a molecular understanding of α-syn–lipid interactions. With the unique approach of NR, we have revealed structural features of the membrane-bound conformation of α-syn that are not observable by other techniques.1,35,36,45 In addition, we have examined the effects of physiologically relevant lipid species on conformational changes, membrane remodeling capabilities, and amyloid formation of α-syn.2,48,56 The interplay between membrane remodeling and protein aggregation could be an important mechanism in how α-syn perturbs and disrupts membrane structure and function, respectively. Furthermore, deformed membranes such as lipid micellar tubes could propagate fibril formation under certain scenarios, exacerbating cytotoxicity.

By using unroofed cells, we have begun to capture the molecular details of membrane-bound α-syn at the cellular plasma membrane.3 We have conclusively shown that α-syn localizes to exocytic sites, where conformational heterogeneity of α-syn is readily apparent, mediated by both N- and C-terminal sites. These unique insights into the inherent plasticity of α-syn are only revealed through the use of cellularly derived membranes, which retain native membrane topology and complexity. Clearly, more work is needed in using biological membranes to deepen our understanding of α-syn–lipid interactions as related to its function and its role in disease.

Of utmost importance, we believe, are investigations into how the membrane influences the conformational switching of α-syn from a functional state to a dysfunctional state. From in vitro data, it is clear that lipids can modulate the α-syn aggregation propensity; however, it remains to be determined on a cellular membrane. In particular, the coupling of microscopy with spectroscopy would yield the spatial context where this occurs. This would be invaluable in aiding the discovery of initiating sites for α-syn accumulation, potentially informing on interventional approaches if specific targets can be identified. We envision that further applications of conformational probes such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements would be particularly useful when coupled with unroofed cells, which are a powerful platform to investigate protein–membrane interactions. Finally, as the methods described herein are broadly applicable, we urge others to apply them to various membrane-associated proteins, including other amyloidogenic peptides, to learn about how the heterogeneous cellular membrane environment can impact protein conformation and function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. We acknowledge the contributions from previous group members (Candace Pfefferkorn, Thai Leong Yap, Zhiping Jiang, Michel de Messieres, Sara Sohail, and Emma O’Leary) and our NR collaborator, Frank Heinrich (National Institute of Standards and Technology).

Biographies

Upneet Kaur received her B.S. in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 2017. She is a Postbaccalaureate Fellow in Dr. Lee’s group, where her work has focused on investigating native α-syn–lipid interactions through biophysical approaches.

Jennifer C. Lee is a Senior Investigator at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Her research efforts are dedicated toward the elucidation of mechanisms of amyloid formation through biophysical and biochemical approaches. She is interested in understanding the chemical nature of intermolecular interactions that drive amyloid formation in a cellular environment. Prior to joining the NIH, she was a Beckman Senior Research Fellow at the Beckman Institute Laser Resource Center at the California Institute of Technology. She obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Caltech in 2002 and has undergraduate degrees in Chemistry and Economics from UC Berkeley.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00453

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Upneet Kaur, Laboratory of Protein Conformation and Dynamics, Biochemistry and Biophysics Center, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States.

Jennifer C. Lee, Laboratory of Protein Conformation and Dynamics, Biochemistry and Biophysics Center, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jiang Z; Heinrich F; McGlinchey RP; Gruschus JM; Lee JC Segmental Deuteration of α-Synuclein for Neutron Reflectometry on Tethered Bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Through the coupled approach of native chemical ligation, for the first time neutron reflectometry was able to distinguish membrane-bound regions within segementally deuterated α-syn.

- (2).Jiang Z; de Messieres M; Lee JC Membrane Remodeling by α-Synuclein and Effects on Amyloid Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 15970–15973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Membrane tubulation of phosphatidylcholine by disordered α-syn is shown to compete with amyloid formation, providing new insights into biological consequences for α-syn-induced membrane remodeling.

- (3).Kaur U; Lee JC Unroofing Site-Specific α-Synuclein Lipid Interactions at the Plasma Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 18977–18983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Site-specific labeling and fluorescence lifetime imaging reveal a multitude of α-syn conformers when α-syn is bound to exocytic sites on the cyotoplasmic membrane, which was achieved through the method of cellular unroofing.

- (4).Lees AJ; Hardy J; Revesz T Parkinson‘s Disease. Lancet 2009, 373, 2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Spillantini MG; Schmidt ML; Lee VM; Trojanowski JQ; Jakes R; Goedert M α-Synuclein in Lewy Bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pankratz N; Foroud T Genetics of Parkinson Disease. Genet. Med 2007, 9, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Fujita Y; Ohama E; Takatama M; Al-Sarraj S; Okamoto K Fragmentation of Golgi Apparatus of Nigral Neurons with α-Synuclein-Positive Inclusions in Patients with Parkinson‘s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 112, 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nakamura K; Nemani VM; Azarbal F; Skibinski G; Levy JM; Egami K; Munishkina L; Zhang J; Gardner B; Wakabayashi J; Sesaki H; Cheng Y; Finkbeiner S; Nussbaum RL; Masliah E; Edwards RH Direct Membrane Association Drives Mitochondrial Fission by the Parkinson Disease-Associated Protein α-Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 20710–20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Meredith GE; Totterdell S; Petroske E; Santa Cruz K; Callison RC Jr.; Lau YS Lysosomal Malfunction Accompanies α-Synuclein Aggregation in a Progressive Mouse Model of Parkinson‘s Disease. Brain Res. 2002, 956, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Clayton DF; George JM The Synucleins: A Family of Proteins Involved in Synaptic Function, Plasticity, Neurodegeneration and Disease. Trends Neurosci. 1998, 21, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Burre J; Vivona S; Diao J; Sharma M; Brunger AT; Sudhof TC Properties of Native Brain α-Synuclein. Nature 2013, 498, E4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Theillet FX; Binolfi A; Bekei B; Martorana A; Rose HM; Stuiver M; Verzini S; Lorenz D; van Rossum M; Goldfarb D; Selenko P Structural Disorder of Monomeric α-Synuclein Persists in Mammalian Cells. Nature 2016, 530, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Eliezer D; Kutluay E; Bussell R Jr.; Browne G Conformational Properties of α-Synuclein in Its Free and Lipid-Associated States. J. Mol. Biol 2001, 307, 1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ulmer TS; Bax A; Cole NB; Nussbaum RL Structure and Dynamics of Micelle-Bound Human α-Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 9595–9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jao CC; Hegde BG; Chen J; Haworth IS; Langen R Structure of Membrane-Bound α-Synuclein from Site-Directed Spin Labeling and Computational Refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 19666–19671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Fusco G; De Simone A; Gopinath T; Vostrikov V; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Veglia G Direct Observation of the Three Regions in α-Synuclein That Determine Its Membrane-Bound Behaviour. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bodner CR; Maltsev AS; Dobson CM; Bax A Differential Phospholipid Binding of α-Synuclein Variants Implicated in Parkinson‘s Disease Revealed by Solution NMR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 862–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fares M-B; Ait-Bouziad N; Dikiy I; Mbefo MK; Jovičić A; Kiely A; Holton JL; Lee SJ; Gitler AD; Eliezer D; Lashuel HA The Novel Parkinson‘s Disease Linked Mutation G51D Attenuates in Vitro Aggregation and Membrane Binding of α-Synuclein, and Enhances Its Secretion and Nuclear Localization in Cells. Hum. Mol. Genet 2014, 23, 4491–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ni X; McGlinchey RP; Jiang J; Lee JC Structural Insights into α-Synuclein Fibril Polymorphism: Effects of Parkinson‘s Disease-Related C-Terminal Truncations. J. Mol. Biol 2019, 431, 3913–3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Pfefferkorn CM; Jiang Z; Lee JC Biophysics of α-Synuclein Membrane Interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2012, 1818, 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jo E; McLaurin J; Yip CM; St. George-Hyslop P; Fraser PE α-Synuclein Membrane Interactions and Lipid Specificity. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 34328–34334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kamp F; Beyer K Binding of α-Synuclein Affects the Lipid Packing in Bilayers of Small Vesicles. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 9251–9259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nuscher B; Kamp F; Mehnert T; Odoy S; Haass C; Kahle PJ; Beyer K α-Synuclein Has a High Affinity for Packing Defects in a Bilayer Membrane: A Thermodynamics Study. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 21966–21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Middleton ER; Rhoades E Effects of Curvature and Composition on α-Synuclein Binding to Lipid Vesicles. Biophys. J 2010, 99, 2279–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).O’Leary EI; Lee JC Interplay between α-Synuclein Amyloid Formation and Membrane Structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2019, 1867, 483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Takamori S; Holt M; Stenius K; Lemke EA; Gronborg M; Riedel D; Urlaub H; Schenck S; Brugger B; Ringler P; Muller SA; Rammner B; Grater F; Hub JS; De Groot BL; Mieskes G; Moriyama Y; Klingauf J; Grubmuller H; Heuser J; Wieland F; Jahn R Molecular Anatomy of a Trafficking Organelle. Cell 2006, 127, 831–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ingólfsson HI; Melo MN; van Eerden FJ; Arnarez C; Lopez CA; Wassenaar TA; Periole X; de Vries AH; Tieleman DP; Marrink SJ Lipid Organization of the Plasma Membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14554–14559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ammar MR; Kassas N; Chasserot-Golaz S; Bader M-F; Vitale N Lipids in Regulated Exocytosis: What Are They Doing. Front. Endocrinol 2013, 4, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rappley I; Myers DS; Milne SB; Ivanova PT; Lavoie MJ; Brown HA; Selkoe DJ Lipidomic Profiling in Mouse Brain Reveals Differences between Ages and Genders, with Smaller Changes Associated with α-Synuclein Genotype. J. Neurochem 2009, 111, 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Giusto NM; Salvador GA; Castagnet PI; Pasquaré SJ; Ilincheta de Boschero MG Age-Associated Changes in Central Nervous System Glycerolipid Composition and Metabolism. Neurochem. Res 2002, 27, 1513–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shahmoradian SH; Lewis AJ; Genoud C; Hench J; Moors TE; Navarro PP; Castaño-Díez D; Schweighauser G; Graff-Meyer A; Goldie KN; Sütterlin R; Huisman E; Ingrassia A; Gier Y.d.; Rozemuller AJM; Wang J; Paepe AD; Erny J; Staempfli A; Hoernschemeyer J; Großerüschkamp F; Niedieker D; El-Mashtoly SF; Quadri M; Van Ijcken WFJ; Bonifati V; Gerwert K; Bohrmann B; Frank S; Britschgi M; Stahlberg H; Van de Berg WDJ; Lauer ME Lewy Pathology in Parkinson‘s Disease Consists of Crowded Organelles and Lipid Membranes. Nat. Neurosci 2019, 22, 1099–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Sidransky E; Nalls MA; Aasly JO; Aharon-Peretz J; Annesi G; Barbosa ER; Bar-Shira A; Berg D; Bras J; Brice A; Chen CM; Clark LN; Condroyer C; De Marco EV; Durr A; Eblan MJ; Fahn S; Farrer MJ; Fung HC; Gan-Or Z; Gasser T; Gershoni-Baruch R; Giladi N; Griffith A; Gurevich T; Januario C; Kropp P; Lang AE; Lee-Chen GJ; Lesage S; Marder K; Mata IF; Mirelman A; Mitsui J; Mizuta I; Nicoletti G; Oliveira C; Ottman R; Orr-Urtreger A; Pereira LV; Quattrone A; Rogaeva E; Rolfs A; Rosenbaum H; Rozenberg R; Samii A; Samaddar T; Schulte C; Sharma M; Singleton A; Spitz M; Tan EK; Tayebi N; Toda T; Troiano AR; Tsuji S; Wittstock M; Wolfsberg TG; Wu YR; Zabetian CP; Zhao Y; Ziegler SG Multicenter Analysis of Glucocerebrosidase Mutations in Parkinson‘s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med 2009, 361, 1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Heinrich F Deuteration in Biological Neutron Reflectometry. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 566, 211–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fragneto-Cusani G Neutron Reflectivity at the Solid/Liquid Interface: Examples of Applications in Biophysics. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2001, 13, 4973–4989. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Pfefferkorn CM; Heinrich F; Sodt AJ; Maltsev AS; Pastor RW; Lee JC Depth of α-Synuclein in a Bilayer Determined by Fluorescence, Neutron Reflectometry, and Computation. Biophys. J 2012, 102, 613–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Jiang Z; Hess SK; Heinrich F; Lee JC Molecular Details of α-Synuclein Membrane Association Revealed by Neutrons and Photons. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 4812–4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).McGlinchey RP; Lee JC Emerging Insights into the Mechanistic Link between α-Synuclein and Glucocerebrosidase in Parkinson‘s Disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans 2013, 41, 1509–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wilkening G; Linke T; Sandhoff K Lysosomal Degradation on Vesicular Membrane Surfaces. Enhanced Glucosylceramide Degradation by Lysosomal Anionic Lipids and Activators. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 30271–30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Aflaki E; Westbroek W; Sidransky E The Complicated Relationship between Gaucher Disease and Parkinsonism: Insights from a Rare Disease. Neuron 2017, 93, 737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Stojkovska I; Krainc D; Mazzulli JR Molecular Mechanisms of α-Synuclein and GBA1 in Parkinson‘s Disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Blumenreich S; Barav OB; Jenkins BJ; Futerman AH Lysosomal Storage Disorders Shed Light on Lysosomal Dysfunction in Parkinson‘s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2020, 21, 4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Toffoli M; Smith L; Schapira AHV The Biochemical Basis of Interactions between Glucocerebrosidase and α-Synuclein in GBA1Mutation Carriers. J. Neurochem 2020, 154, 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Yap TL; Gruschus JM; Velayati A; Westbroek W; Goldin E; Moaven N; Sidransky E; Lee JC α-Synuclein Interacts with Glucocerebrosidase Providing a Molecular Link between Parkinson and Gaucher Diseases. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 28080–28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yap TL; Velayati A; Sidransky E; Lee JC Membrane-Bound α-Synuclein Interacts with Glucocerebrosidase and Inhibits Enzyme Activity. Mol. Genet. Metab 2013, 108, 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yap TL; Jiang Z; Heinrich F; Gruschus JM; Pfefferkorn CM; Barros M; Curtis JE; Sidransky E; Lee JC Structural Features of Membrane-Bound Glucocerebrosidase and α-Synuclein Probed by Neutron Reflectometry and Fluorescence Spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 744–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Varkey J; Isas JM; Mizuno N; Jensen MB; Bhatia VK; Jao CC; Petrlova J; Voss JC; Stamou DG; Steven AC; Langen R Membrane Curvature Induction and Tubulation Are Common Features of Synucleins and Apolipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 32486–32493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Varkey J; Mizuno N; Hegde BG; Cheng N; Steven AC; Langen R α-Synuclein Oligomers with Broken Helical Conformation Form Lipoprotein Nanoparticles. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 17620–17630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Jiang Z; Flynn JD; Teague WE Jr.; Gawrisch K; Lee JC Stimulation of α-Synuclein Amyloid Formation by Phosphatidylglycerol Micellar Tubules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2018, 1860, 1840–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Biancalana M; Koide S Molecular Mechanism of Thioflavin-T Binding to Amyloid Fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804, 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Vance JE Phosphatidylserine and Phosphatidylethanolamine in Mammalian Cells: Two Metabolically Related Aminophospholipids. J. Lipid Res 2008, 49, 1377–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).van Meer G; Voelker DR; Feigenson GW Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2008, 9, 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Mizuno N; Varkey J; Kegulian NC; Hegde BG; Cheng NQ; Langen R; Steven AC Remodeling of Lipid Vesicles into Cylindrical Micelles by α-Synuclein in an Extended α-Helical Conformation. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 29301–29311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Westphal CH; Chandra SS Monomeric Synucleins Generate Membrane Curvature. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 1829–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Quinn PJ; Wolf C The Liquid-Ordered Phase in Membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2009, 1788, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Galvagnion C The Role of Lipids Interacting with α-Synuclein in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson‘s Disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis 2017, 7, 433–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).O’Leary EI; Jiang Z; Strub MP; Lee JC Effects of Phosphatidylcholine Membrane Fluidity on the Conformation and Aggregation of N-Terminally Acetylated α-Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 11195–11205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Heuser J The Production of ‘Cell Cortices‘ for Light and Electron Microscopy. Traffic 2000, 1, 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Simons K; Ikonen E Functional Rafts in Cell Membranes. Nature 1997, 387, 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Ghosh PB; Whitehouse MW 7-Chloro-4-Nitrobenzo-2-Oxa-1,3-Diazole - a New Fluorigenic Reagent for Amino Acids and Other Amines. Biochem. J 1968, 108, 155–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Burre J; Sharma M; Tsetsenis T; Buchman V; Etherton MR; Sudhof TC α-Synuclein Promotes SNARE-Complex Assembly in Vivo and in Vitro. Science 2010, 329, 1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Diao J; Burre J; Vivona S; Cipriano DJ; Sharma M; Kyoung M; Sudhof TC; Brunger AT Native α-Synuclein Induces Clustering of Synaptic-Vesicle Mimics Via Binding to Phospholipids and Synaptobrevin-2/Vamp2. eLife 2013, 2, e00592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Burre J; Sharma M; Sudhof TC α-Synuclein Assembles into Higher-Order Multimers Upon Membrane Binding to Promote Snare Complex Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111, E4274–4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]