Abstract

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is known to be a crucial regulator in the post-synapse during long-term potentiation. This important protein has been the subject of many studies centered on understanding memory at the molecular, cellular, and organismic level. CaMKII is encoded by four genes in humans, all of which undergo alternative splicing at the RNA level, leading to an enormous diversity of expressed proteins. Advances in sequencing technologies have facilitated the discovery of many new CaMKII transcripts. To date, newly discovered CaMKII transcripts have been incorporated into an ambiguous naming scheme. Herein, we review the initial experiments leading to the discovery of CaMKII and its subsequent variants. We propose the adoption of a new, unambiguous naming scheme for CaMKII variants. Finally, we discuss biological implications for CaMKII splice variants.

Introduction

The topic of this review is the fascinating enzyme: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). CaMKII is known to be essential to long-term potentiation (LTP), a key component of the cellular basis of memory (Herring and Nicoll, 2016). Clear evidence for this role derives from studying transgenic mice carrying a mutation in CaMKIIα at a key autophosphorylation site (Thr286Ala). These mutant mice displayed spatial learning deficits (Giese et al., 1998). Intriguingly, transgenic mice harboring mutations in CaMKIIα at other key autophosphorylation sites known to be inhibitory (Thr305Val/306Ala) exhibit a distinct memory phenotype where the mice displayed rigid learning (Elgersma et al., 2002). The fact that the two genotypes produce distinct phenotypes suggests that CaMKII may indeed be playing multiple roles in memory formation and storage. These results, and others, have spurred decades of study on the role of CaMKII in memory.

In this review, we highlight the complexity of CaMKII at the sequence level. Several studies have detailed the implications of numerous splice variants (Sloutsky et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2018; Suzuki et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2009; Tombes et al., 2003), yet the nomenclature to distinguish one variant from another has long been a point of confusion in the field. We have compiled a timeline of the discovery of CaMKII and its specific splice variants over the past several decades and now propose a new naming scheme, which will allow for incorporation of any newly discovered variants. Finally, we comment on the biological ramifications of having this amazing diversity encoded into the primary sequence of CaMKII genes.

CaMKII gene architecture

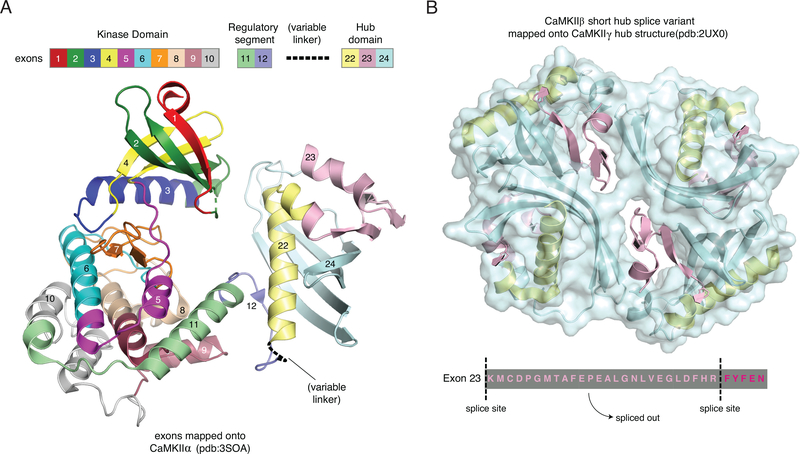

CaMKII is encoded on four genes in vertebrates: CaMKIIα, β, γ, and δ. All four genes are expressed in the brain, but CaMKIIα and β are the predominant variants implicated in LTP (Incontro et al., 2018; Herring and Nicoll, 2016). CaMKIIγ is expressed throughout the body, including egg and sperm, where it plays a major role in fertilization (Yoon et al., 2008; Escoffier et al., 2016). CaMKIIδ is the major variant expressed in the heart and plays a role in cardiac pacemaking (Maier and Bers, 2002; Backs et al., 2009). Each CaMKII subunit is comprised of a kinase domain (exons 1–10), regulatory segment (exons 11–12), variable linker region (exons 13–21), and a hub domain (exons 22–24) (Fig. 1A). Exon boundaries are highly conserved between all four genes across vertebrates (Fig. 2A). The kinase and hub domains are highly conserved across the four genes, with minimum 90% and 75% pairwise identity, respectively. The linker that connects the kinase and hub domains is highly variable in length and composition due to alternative splicing between linker exons. Additional splice sites are found within the kinase domain of CaMKIIδ (exon 6) and the hub domain of CaMKIIβ (exon 23) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1:

Exon architecture of CaMKII. (A) One subunit of CaMKII highlighting exon boundaries in the kinase domain, regulatory segment and hub domain. Exon boundaries are mapped onto a subunit of the holoenzyme crystal structure in ribbon diagram (pdb:3SOA). Colors match the linear depiction above. There is no variable linker in this structure; the black dashed line indicates where the linker would be. (B) Exon boundaries are mapped onto a ribbon diagram for a tetramer of the hub domain (pdb:2UXO). Highlighted below is exon 23, which is alternatively spliced only in CaMKIIβ. The 26 residues that are spliced out of exon 23 are not included in the surface representation of the hub domain, highlighting a short helix and two beta turns that would be missing in this splice variant.

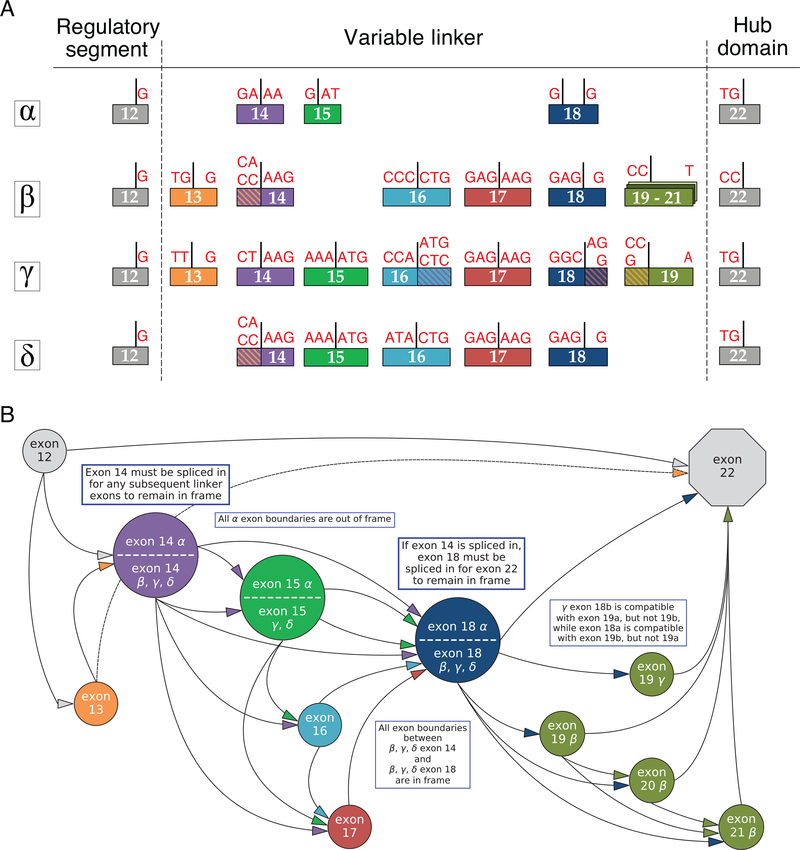

Figure 2:

(A) Alternative splicing in the CaMKII variable linker region. All exon boundaries are shown where there is alternative splicing in the variable linker region. For simplicity, only the exons flanking the variable linker (exons 12 and 22) are shown. Nucleotides comprising codons at exon junctions are shown in red letters. Only the extreme 5’ and 3’ bases are denoted for each exon. Exons colored with hashed lines indicate internal splice sites, with the corresponding a (top) or b (bottom) nucelotides. (B) Linker splicing rules imposed by codons at the 5’ and 3’ ends of linker exons. Splicing of incompatible exons results in a frameshift. Arrows indicate compatible exon junctions. Any path from exon 12 to exon 22 along compatible exon junctions constitutes an in-frame splice variant. Every linker must contain exons 14 and 18 in order for exons to be translated in frame, with the exception of a junction between exons 13 (CaMKIIβ and γ) and 22, indicated by the dashed arrow, which also maintains exon 22 in frame.

On close inspection of the splice sites at the codon level, it is clear that not all exon connections would be in the correct reading frame (Fig. 2A). For example, exon 12 always has a single “G” and the 3’ end, so the subsequent exon must have 2 bases at the 5’ end to complete a codon. All four genes are conducive to having all linker exons spliced out, since exon 22 always contains 2 bases at the 5’ end. The requirement to remain in frame introduces a number of additional constraints on linker exon connectivity, which are summarized in Fig. 2B.

These complexities of CaMKII at the sequence level have led to some confusion over the years in terms of classifying variants in a consistent manner. We review here the history of CaMKII and its splice variants, as well as propose a naming scheme moving forward.

CaMKII splice variants

Historical perspective

It was discovered in 1970 that the Ca2+-dependent activation of cyclic 3’,5’-nucleotide phosphodiesterase required a protein mediator (Cheung, 1971; Kakiuchi and Yamazaki, 1970; Cheung, 1970; Kakiuchi et al., 1970). Throughout the 1970s, this protein was commonly referred to as a “calcium-dependent regulator” (CDR) (Schulman and Greengard, 1978b,a) of a much broader spectrum of Ca2+-dependent biological processes (Cheung, 1980), now known as calmodulin. One such process mediated by calmodulin was found to be Ca2+-dependent protein phosphorylation (Stull et al., 1986; Edelman et al., 1987). The late 1970s and early 1980s were filled with discoveries and characterization of protein kinases whose Ca2+-dependent activation is mediated by calmodulin. Myosin light chain kinase (Dabrowska et al., 1978; Yagi et al., 1978; Nairn and Perry, 1979) and phosphorylase kinase (Shenolikar et al., 1979; Cohen et al., 1978), which had already been known to be Ca2+-dependent, were quickly shown to be Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent (Ca2+/CaM). Shortly thereafter, researchers discovered additional Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase activity in multiple tissues that was not associated with either myosin light chain kinase or phosphorylase kinase. In the brain, these were responsible for the Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of tryptophan 5-monooxygenase (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1980), tyrosine 3-monooxygenase (Yamauchi et al., 1981), synaptic protein I (later known as synapsin I) (Kennedy and Greengard, 1981), tubulin (Goldenring et al., 1983), and microtubule-associated protein 2 (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1982). A Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase acting on glycogen synthase was identified in liver (Payne and Soderling, 1980) and skeletal muscle (Woodgett et al., 1982). Once purified, some of these Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases could also phosphorylate casein (Woodgett et al., 1982; Fukunaga et al., 1982), myelin basic protein, and histones (Goldenring et al., 1983; Fukunaga et al., 1982; Ahmad et al., 1982). In each case, the molecular mass of the native enzyme was inferred to be in the range of 500 to 850 kDa, (Goldenring et al., 1983; Woodgett et al., 1982; Fukunaga et al., 1982; Ahmad et al., 1982), composed of subunits ranging from 49 to 63 kDa (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1980; Goldenring et al., 1983; Fukunaga et al., 1982; Ahmad et al., 1982; Payne et al., 1983).

1983 was a particularly busy year in the investigation of Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases. Two Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases separable by fractionation had been found to phosphorylate distinct Ser/Thr sites on synapsin I (site I: CaMKI and site II: CaMKII) (Kennedy and Greengard, 1981). Site II kinase was partially (Kennedy et al., 1983), and then, crucially, fully purified (Bennett et al., 1983) from brain tissue. All three gel bands of the partially purified kinase were autophosphorylated (Kennedy et al., 1983). The complete purification provided evidence that the gel bands corresponding to 50, 58, and 60 kDa were indeed subunits of the kinase itself (Bennett et al., 1983). While it had already been shown that subunits of glycogen synthase kinase from both liver (Ahmad et al., 1982) and skeletal muscle (Woodgett et al., 1983) autophosphorylate in vitro, the 50, 58, and 60/61 kDa gel bands of partially purified brain synapsin I site II kinase were shown to correspond to three major targets of Ca2+/CaM-dependent phosphorylation previously identified in homogenates from brain and several other tissues (Schulman and Greengard, 1978b,a). Taken together, these results suggested for the first time that autophosphorylation is likely to be a physiologically relevant phenomenon (Kennedy et al., 1983; Bennett et al., 1983).

Also in 1983, Ca2+/CaM-dependent glycogen synthase kinase (now known to be CaMKII) was purified from skeletal muscle as a 696 kDa holoenzyme consisting primarily of 58 kDa subunits with a minor contribution of 54 kDa subunits. A dodecameric holoenzyme made up of roughly nine 50 kDa and three 58/60 kDa subunits had been postulated a month earlier for synapsin I site II kinase based on a 650 kDa native holoenzyme (Bennett et al., 1983). For the purified glycogen synthase kinase, the authors hypothesized a quaternary structure of the dodecameric holoenzyme consisting of two stacked hexameric rings, based on the first-ever electron micrographs of native glycogen synthase kinase clearly showing a 6-fold symmetric hub-and-spokes arrangement, and on the exact 12-fold ratio of holoenzyme mass (696 kDa) to primary subunit mass (58 kDa) (Woodgett et al., 1983). Aside from their obvious structural similarities, little suggested that Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases from brain and glycogen synthase kinase from liver and skeletal muscle might be the same enzyme until one such kinase purified from brain was shown to effectively phosphorylate glycogen synthase purified from skeletal muscle (Iwasa et al., 1983). Then, based on extremely similar subunit compositions, phosphopeptide maps, and rates of phosphorylation across panels of substrates, first synapsin I kinase and glycogen synthase from skeletal muscle (McGuinness et al., 1983a), and then another brain Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase (Woodgett et al., 1984), were all demonstrated indeed to be the same enzyme expressed in different tissues. This prompted synergy of separate investigations of synapsin I kinase (Kennedy and Greengard, 1981; Kennedy et al., 1983; Bennett et al., 1983), other brain Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1980; Yamauchi et al., 1981; Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1982; Fukunaga et al., 1982; Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1983; Goldenring et al., 1983; Iwasa et al., 1983) and glycogen synthase kinase from multiple tissues (Payne and Soderling, 1980; Woodgett et al., 1982; Ahmad et al., 1982; Woodgett et al., 1983; Payne et al., 1983). The authors declared the enzyme “a multifunctional calmodulin-dependent protein kinase that mediates many of the actions of Ca2+ in various tissues” (McGuinness et al., 1983a).

In late 1983, the name Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) appeared for the first time in conference abstracts (Lai et al., 1983; McGuinness et al., 1983b). The origin of the name is not explicitly clear from the literature. In 1980, Yamauchi and Fujisawa (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1980) identified three distinct brain Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases eluting in separate gel filtration fractions, with a fourth eluting in the void volume, and referred to these as kinases I through IV. Their analysis suggested that kinase I corresponded to phosphorylase kinase, kinase III corresponded to myosin light chain kinase, kinase IV was likely a heterogeneous mixture of aggregates, while kinase II was an unknown kinase. Starting in 1982, Yamauchi and Fujisawa refer to this enzyme as CaM-dependent protein kinase (kinase II) (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1982, 1983). Separately, in 1981 Kennedy and Greengard had observed two distinct brain Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases (Kennedy and Greengard, 1981), each phosphorylating synapsin I at a unique site. Titles of 1983 conference abstracts from the Greengard laboratory referred to CaMKII (Lai et al., 1983; McGuinness et al., 1983b), while another abstract from the same lab referred to CaMKI (Nairn and Greengard, 1983). A 1984 conference abstract by Nairn and Greengard (Nairn and Greengard, 1984) described CaMKI as distinct from CaMKII. Nestler and Greengard stated that CaMKI phosphorylates site 1 on synapsin I, while CaMKII phosphorylates sites 2 and 3, citing the conference abstracts from 1983 (Nestler and Greengard, 1984). So, although the first research paper on CaMKI did not appear until 1987 (Nairn and Greengard, 1987), it appears that CaMKI and CaMKII may have been named at the same time in 1983, based on the sites they phosphorylate on synapsin I. Furthermore, CaMKIII appears to have been identified as distinct from CaMKI and CaMKII and named by Nairn, Bhagat, and Palfrey around the same time (Palfrey, 1983; Nairn et al., 1985). However, this naming scheme was not universally adopted until later, as in 1986 “type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase” (Miller and Kennedy, 1986), and even simply “multifunctional calmodulin-dependent protein kinases” (Stull et al., 1986) were also used.

Most critical to the topic of this review, in 1983 Mary Kennedy’s lab named the 50 kDa, 60 kDa, and 58 kDa subunits of “calmodulin-dependent synapsin I kinase” as α, β, and β', (Bennett et al., 1983). Subunits distinguishable by SDS-PAGE analysis had previously been named α and β (Ahmad et al., 1982), and ρ and σ (Goldenring et al., 1983), but these names did not persist beyond the publications in which they were introduced. Bennett et al. correctly distinguished α from β/β' based on similar, but not identical phosphopeptide maps of their phosphorylated forms and on selective binding by a monoclonal antibody. Once substantial evidence had accumulated for “isozymes” comprised of multiple polypeptide subunits being present in multiple tissues (Kelly et al., 1984; Schworer et al., 1985; Miller and Kennedy, 1985; Shenolikar et al., 1986), the stage was set for a definitive determination of subunit expression by nucleotide sequencing.

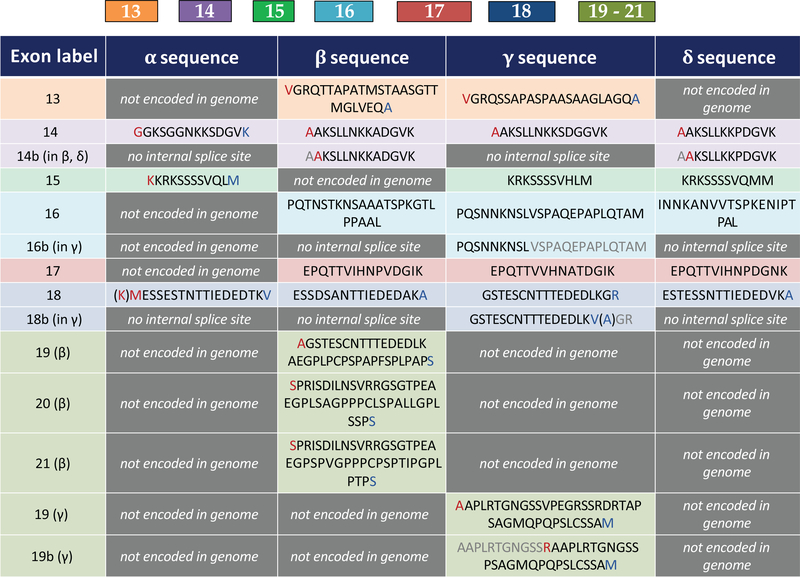

The first two coding sequences of brain CaMKII were reported almost simultaneously by three groups in 1987. cDNA encoding the brain polypeptide designated α (Bennett et al., 1983) was identified from brain cDNA libraries by hybridization with synthetic oligonucleotides designed to match tryptic fragments derived from the 50 kDa brain CaMKII subunit and sequenced by Edman degradation (Lin et al., 1987). Another group identified the cDNA encoding the β polypeptide by screening proteins expressed from a brain cDNA expression library (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987) against anti-CaMKII antibodies they had previously raised (Miller and Kennedy, 1985). A third group used a similar antibody screening strategy to identify and sequence an α fragment cDNA (Hanley et al., 1987). The α and β full-length cDNAs were sequenced to derive predicted 478 amino acid α (Lin et al., 1987) and 542 amino acid β (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987) polypeptides with molecular weights of 54 kDa and 60 kDa, respectively. Homology analysis of both proteins indicated N-terminal kinase domains similar in sequence to previously determined Ca2+/CaM-dependent phosphorylase and myosin light chain kinases, and several other protein kinases (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987; Hanley et al., 1987; Lin et al., 1987). The kinase domains were followed by stretches of basic residues similar to calmodulin binding sites previously identified in myosin light chain and phosphorylase kinases (Blumenthal et al., 1985; Lukas et al., 1986). A synthetic 25 amino acid peptide, derived from the putative CaMKIIα calmodulin binding site and flanking sequence, bound to calmodulin in the presence of Ca2+. The remaining C-terminal amino acid sequences of both α and β lacked any known homology, but were correctly hypothesized to be involved in oligomerization (now known as the hub domain) (Lin et al., 1987). Two of seven β cDNA clones had identical in-frame 45 nucleotide deletions relative to the remaining five clones, encoding a 58 kDa predicted polypeptide missing 15 residues relative to the 60 kDa β polypeptide. Based on this, the authors correctly hypothesized that the 58 kDa gel band they had previously designated β' (Bennett et al., 1983) reflected a distinct polypeptide species resulting from alternative splicing of the β transcript, rather than a product of proteolysis (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987). We now know this 45 nucleotide sequence to be CaMKIIβ exon 17 (Fig. 3). Comparison of α and β/β' coding sequences suggested that the two were products of different, but homologous genes (Hanley et al., 1987; Lin et al., 1987). In a 1988 follow-up to the earliest 1987 report (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987), cDNAs for all three polypeptides were identified from the same brain cDNA libraries, confirming the distinct genomic origins of α and β/β' and reinforcing the case for the alternative splicing origin of β and β' (Bulleit et al., 1988).

Figure 3:

Linker exon sequences for all CaMKII genes. Residues highlighted in red are partially encoded in the preceding exon (due to split codons, see Fig. 2). Residues highlighted in blue are partially encoded in the subsequent exon. Residues in parentheses indicate that the identity of that residue is conditional on the preceding or subsequent exon. Residues highlighted in gray are spliced out due to internal splice sites (14b, 16b, 18b, 19b)

Over the following two years, transcripts from two additional CaMKII genes were identified and the corresponding polypeptides named γ and δ, in keeping with the existing naming scheme (Tobimatsu et al., 1988; Tobimatsu and Fujisawa, 1989). In 1988, a brain cDNA library was screened for CaMKII coding sequences by hybridization to an oligonucleotide complementary to a fragment of the previously published CaMKIIβ coding sequence (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987). In addition to four clones matching the published α coding sequence (Lin et al., 1987), and another four clones matching β (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987), a ninth clone was found to encode a highly homologous, but distinct 527 amino acid, 59 kDa polypeptide, designated γ. Based on the alignment of α, β, and γ, the authors noted two regions of greater homology at the N-terminal (approximately 315 residues) and C-terminal (approximately 150 residues in γ) ends of all three sequences, flanking a shorter middle region (approximately 60 residues in γ) with significantly lower homology, which the authors designated the divergent region (“D-region”), and suggested may not be “essential for kinase activity” (Tobimatsu et al., 1988). We now know the homology among linker exons to be substantially higher than initially appreciated (Fig. 2A), and the initial over-estimation of divergence having resulted from alignment of non-homologous linker exons. The following year, the same group used this β antisense oligonucleotide screening approach to isolate CaMKII cDNAs from a cerebellum cDNA library. In addition to α, β, and the γ they had already identified, they sequenced a fourth distinct cDNA sequence encoding a 533 amino acid, 60 kDa polypeptide, which they designated δ. By the authors’ count, this brought the number of known CaMKII coding sequences to five: α, β, β', γ, and δ (Tobimatsu and Fujisawa, 1989). Although the authors presumed that “[f]urther investigation [would] reveal the existence of additional members of the CaM-kinase II gene family”, they had already identified the fourth and final CaMKII-encoding gene in mammals. With all four genes now identified, detection of additional splice variants became substantially easier by using targeted PCR with primers designed against the known coding sequences. Now the stage was set for an explosion in the number of identified variants. With any explosion, there is an associated level of chaos. Since it could not be known in advance how many variants would be discovered, initial CaMKII variant naming strategies differed from group to group. This was compounded by the fact that many papers were published simultaneously, not allowing enough incubation time to adopt a uniform naming scheme in the field.

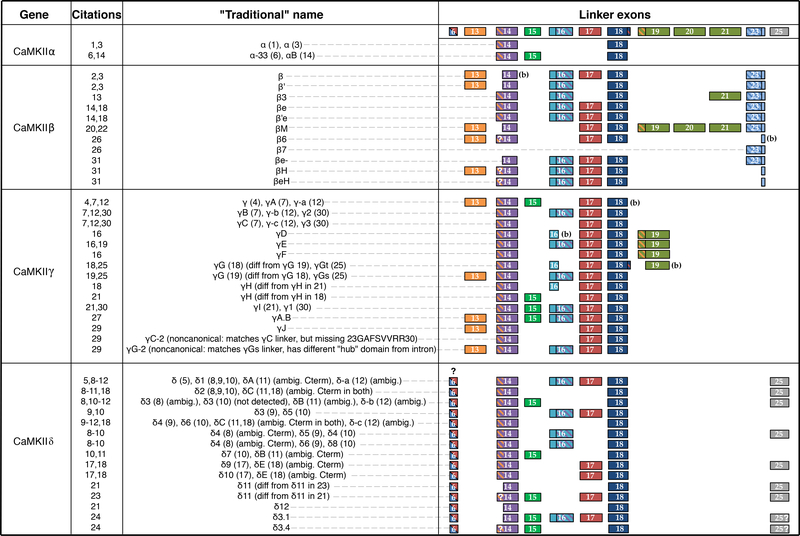

Nearly all preceding work had been carried out in rat and rabbit tissues. In 1991, a second α splice variant containing 33 additional nucleotides, now known as linker exon 15 (Fig. 3), was identified in monkey visual cortex and designated α-33 (Benson et al., 1991). When the same variant was detected in rat brain four years later, it was designated αB, presumably because of the different species (Brocke et al., 1995). Identification of γ and δ variants by multiple groups occurred so rapidly in 1993 and 1994 that near-simultaneous publications repeatedly assigned different names to the same δ variants. One manuscript identified three new δ splice variants in addition to the original δ (renamed as δ1) and labeled the new variants δ2-δ4 (Schworer et al., 1993). While that manuscript was in review, another manuscript identified a different collection of five new δ variants and named these δ2-δ6, with the original variant again renamed δ1 (Mayer et al., 1993). However, δ4 in the first publication corresponded to either δ5 or δ6 in the second publication, due to ambiguity at the C-terminal of CaMKIIδ transcripts (Fig. 4), which was not sequenced in the first manuscript. A third manuscript defined two new variants: δB (=δ3) and δC (=δ2) (Edman and Schulman, 1994). A fourth manuscript submitted at the same time labeled the corresponding variants δ-b (=δ3=δB), δ-c (=δ2=δC), and δ-a (=δ1=δA) (Zhou and Ikebe, 1994). Authors of the second manuscript (Pfeiffer and colleagues) adopted the numbering scheme laid out in the first manuscript in their subsequent publications (Mayer et al., 1994a). Nonetheless, the conflicting number and letter naming schemes persisted. Similarly, in human T lymphocytes, the original γ was renamed γA, and additional variants were named γB and γC (Nghiem et al., 1993). The fourth manuscript acknowledged this naming scheme, but retained their own γ-a, γ-b, and γ-c designations for the corresponding variants detected in rat aorta smooth muscle, presumably because the sequence of γ exon 16 differs between rat and human (Zhou and Ikebe, 1994). These variants and their given names are summarized in Fig. 4.

Figure 4:

Historical designations of CaMKII variants. Sequences compiled for all four CaMKII genes, including the name the variant was given in the corresponding citation. Under ‘linker exons’ are all exons that are alternatively spliced. Question marks indicate ambiguity from the original reference due to lack of sequencing in the corresponding region. Hashed lines in exons indicate an internal splice site, where “(b)” indicates the short version truncated at the internal splice site. References: (1) (Lin et al., 1987); (2) (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987); (3) (Bulleit et al., 1988); (4) (Tobimatsu et al., 1988); (5) (Tobimatsu and Fujisawa, 1989); (6) (Benson et al., 1991); (7) (Nghiem et al., 1993); (8) (Schworer et al., 1993); (9) (Mayer et al., 1993); (10) (Mayer et al., 1994b); (11) (Edman and Schulman, 1994); (12) (Zhou and Ikebe, 1994); (13) (Urquidi and Ashcroft, 1995); (14) (Brocke et al., 1995); (16) (Kwiatkowski and McGill, 1995); (17) (Mayer et al., 1995); (18) (Tombes and Krystal, 1997); (19) (Singer et al., 1997); (20) (Bayer et al., 1998); (21) (Takeuchi and Fujisawa, 1998); (22) (Bayer et al., 1999); (23) (Hoch et al., 1999); (24) (Takeuchi et al., 1999); (25) (Kwiatkowski and McGill, 2000); (26) (Wang et al., 2000); (27) (Takeuchi et al., 2000); (29) (Gangopadhyay et al., 2003); (30) (Chang et al., 2009); (31) (Cook et al., 2018)

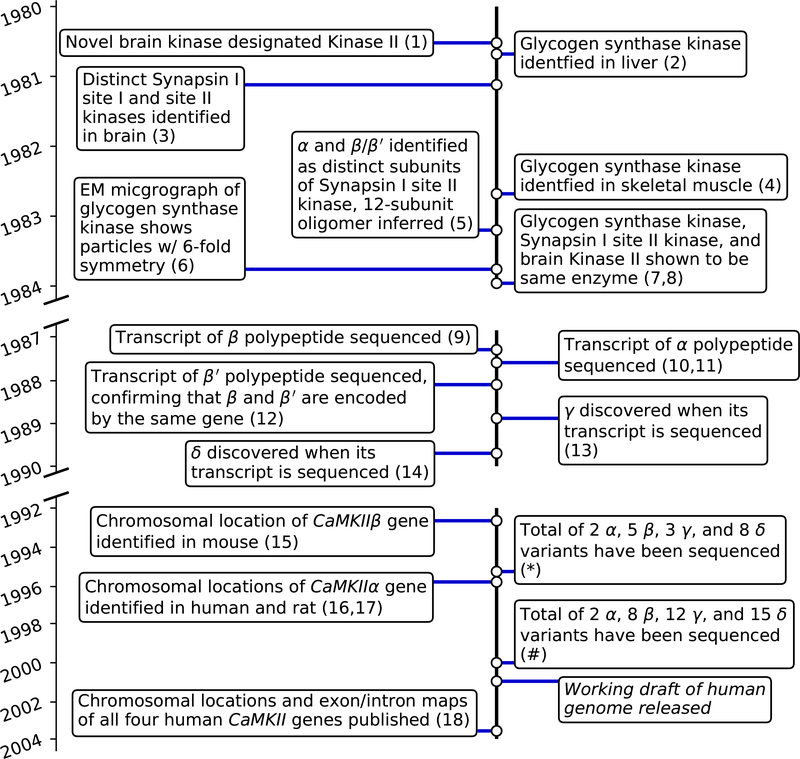

Numerous additional variants of γ and δ were identified between 1995 and 2003, with conflicting naming schemes and occasional name clashes (Kwiatkowski and McGill, 1995; Mayer et al., 1995; Tombes and Krystal, 1997; Singer et al., 1997; Takeuchi and Fujisawa, 1998; Hoch et al., 1999; Takeuchi et al., 1999; Kwiatkowski and McGill, 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2000; Gangopadhyay et al., 2003) (Figure 4). During the same period, a number of β variants were also discovered (Urquidi and Ashcroft, 1995; Brocke et al., 1995; Tombes and Krystal, 1997; Bayer et al., 1998, 1999; Wang et al., 2000) and, fortunately, name clashes were avoided (Figure 4). CaMKIIβ was also the first CaMKII gene to have its genomic location identified in mouse through a fortuitous accident in 1992 (Karls et al., 1992). The genomic location of the CaMKIIα gene was determined over the course of multiple targeted studies in 1995 and 1996 (Olson et al., 1995; Nishioka et al., 1996). Genomic locations of CaMKIIγ and δ would not be known until the completion of human genome, reported in a 2003 review of CaMKII alternative splicing by Tombes and colleagues (Tombes et al., 2003). 2003 also marked the effective end of the CaMKII splice variant discovery explosion, with the identification of several rare γ variants in smooth muscle (Gangopadhyay et al., 2003) (Figure 4). Variants labeled γ1-γ3 were reported in egg cells in 2009 (Chang et al., 2009), but these matched variants reported earlier in other tissues (Zhou and Ikebe, 1994; Nghiem et al., 1993; Takeuchi and Fujisawa, 1998) (Figure 4). The intriguing CaMKIIβ variant where a splicing event causes a shorter hub version was first reported as β6 in 2000 (Wang et al., 2000). Additional short hub variants were recently discovered and named βH and βeH in 2018 (Cook et al., 2018), although the full coding sequences of these variants were not reported. The most crucial findings from the past 40 years of CaMKII splice variant discovery are highlighted in the timeline in Fig. 5.

Figure 5:

Timeline of key events in the discovery of CaMKII and its splice variants. References: (1) (Yamauchi and Fujisawa, 1980); (2) (Payne and Soderling, 1980); (3) (Kennedy and Greengard, 1981); (4) (Woodgett et al., 1982); (5) (Bennett et al., 1983); (6) (Woodgett et al., 1983); (7) (McGuinness et al., 1983a); (8) (Woodgett et al., 1984); (9) (Bennett and Kennedy, 1987); (10) (Lin et al., 1987); (11) (Hanley et al., 1987); (12) (Bulleit et al., 1988); (13) (Tobimatsu et al., 1988); (14) (Tobimatsu and Fujisawa, 1989); (15) (Karls et al., 1992); (16) (Olson et al., 1995); (17) (Nishioka et al., 1996); (18) (Tombes et al., 2003); (*,#) see Fig. 5 for all references in which new CaMKII splice variants were introduced

With the limits of less-abundant variant discovery by traditional PCR and Sanger sequencing approaches apparently reached, no additional variants were identified between 2003 and present day, until a recent study used an Illumina sequencing strategy to detect an unprecedented number of variants of all four genes, including numerous previously un-described variants, in three human hippocampus samples (Sloutsky et al., 2020). Across the four sequenced samples, 3 CaMKIIα, 14 CaMKIIβ, 11 CaMKIIγ, and 6 CaMKIIδ transcripts were robustly detected, with nearly 80 variants detected in at least one sample. A brief summary of the highest-detected variants is presented in the next section. Detection of this unexpectedly large number of variants from individual tissue samples is nearly impossible by traditional sequencing approaches because of the three to four orders of magnitude differences in variant detection level and the extreme difficulty of resolving the variants as individual bands on agarose DNA gels.

Systematic splice variant nomenclature

We propose the implementation of a new naming scheme for CaMKII splice variants using a simple formula for composing variant names: species, gene identity, and incorporated exons. For example, human CaMKIIα(14,15,18) would designate the variant of CaMKIIα where all linker exons (14, 15, and 18) are incorporated. For variants that contain zero linker exons, we propose designating these with −0, where CaMKIIα with no linker exons would be: CaMKIIα-0. There are additional splice sites within exons of certain genes: exon 14 in CaMKIIβ and δ, exons 16, 18, and 19 in CaMKIIγ, and exon 23 in the hub domain of CaMKIIβ. Splicing at one of these sites produces a shortened version of the corresponding exon. In these cases, the full version of the exon should be designated “a”, while the short version should be designated “b” to indicate truncation at the internal splice site. For example, human CaMKIIβ(13, 14b,16,18,23a) designates a variant of CaMKIIβ where exon 14 is spliced to produce the shorter form, while exon 23 is not spliced at its secondary site, producing its longer form. Finally, CaMKIIδ encodes two versions of exon 6 that differ at 5 of the 24 residues encoded by that exon. This is different from internal splice sites, as both exons are of equal length and are encoded in the genome sequentially with an intron between them. For these, we propose using 6v1 and 6v2 nomenclature to designate the more-frequently (6v1) and less-frequently (6v2) incorporated versions of the exon. CaMKIIδ variants should always incorporate 6v1 or 6v2 in their names. This is a flexible way to efficiently catalog currently documented CaMKII variants. Importantly, this strategy allows incorporation of newly discovered variants with any exon connectivity.

As examples of the proposed nomenclature, here we will summarize the highest-detected human hippocampal variants in (Sloutsky et al., 2020). CaMKIIα(14,18) (30-residue linker) and CaMKIIβ(13,14b,16,17,18) (93-residue linker) were the highest-detected splice variants of the corresponding genes, accounting for 70–95% of α reads and 36–56% of β reads, respectively. There were no consensus top variants of CaMKIIγ or CaMKIIδ. However, CaMKIIγ(14,16a,17,18b) (69-residue linker) averaged the most reads across all samples, ranging from 24–38%, and CaMKIIγ(6v1,14b,18) (28-residue linker) accounted for 26–53% of reads. A version of the CaMKIIγ variant incorporating exon 6v2, CaMKIIγ(6v2,14b,18) (28-residue linker), was also detected in all samples.

Biological impact of CaMKII alternative splicing

Protein-protein interactions and sub-cellular localization facilitated by linker exons

There are many facets to the biological impact of the variable linker in CaMKII. Given the high degree of conservation between the four vertebrate CaMKII genes, the linker is the most obvious candidate for the region that confers unique attributes to each splice variant. One way nature has exploited this is to encode binding sites for specific interaction partners in individual exons. This facilitates a diverse set of interacting partners for each splice variant. To date, clear roles have only been identified for two exons. One is F-actin binding, a functionality encoded on exon 13 (encoded only in CaMKIIβ and γ genes) (O’Leary et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2019). Thus, CaMKIIβ and γ are able to localize to F-actin as long as exon 13 is spliced in. Exon 15, encoded in all genes except CaMKIIβ, contains a nuclear localization sequence, facilitating translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

There are likely other binding sites encoded in, or facilitated by, the linker that have yet to be discovered. Interactions that have been shown to be variant- or gene-specific may indicate involvement of the variable linker region. Indeed, Tsien and colleagues worked out a complex mechanism whereby specific variants of CaMKII (α, β, γ) are recruited to the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) or NMDA receptor in an activation-dependent manner (Ma et al., 2014). CaMKIIγ contains a nuclear localization sequence (NLS, exon 15), causing it to translocate to the nucleus with Ca2+/CaM upon phosphorylation by CaMKIIα/β. This signaling cascade ultimately results in gene expression changes that drive synaptic plasticity and long-term memory (Ma et al., 2014). CaMKIIβ does not encode exon 15, and the CaMKIIα splice variant containing exon 15 is not strongly expressed in the hippocampus (Sloutsky et al., 2020). Thus, CaMKIIα/β is incapable of translocating to the nucleus.

In an elegant study from Colbran and colleagues, a binding site on the N-terminal domain of LTCC and residues on CaMKII required for binding that site were elucidated (Wang et al., 2017). The required residues are localized on the kinase domain, and are present in all variants – yet only 2–3 variants of CaMKII (α/β, γ) are recruited to the LTCC. It is feasible that the variable linker may also interact with the kinase domain to facilitate or block specific interactions, but further studies are needed to fully understand all of the interactions between CaMKII and the CaMKII Anchoring Proteins (Colbran, 2004) / CaMKII-Associated Proteins (Robison et al., 2005) (CaMKAPs). Colbran and colleagues also performed a comprehensive mass spectrometry analysis of phosphorylation sites on CaMKII as well as CaMKAP identification (Baucum et al., 2015). Extensive phosphorylation is a characteristic of disordered protein regions (Gao and Xu, 2012), and many phosphorylation sites in the variable linkers of CaMKIIα and β were identified in this study, including sites within the actin-binding domain of CaMKIIβ. There are additional annotated and predicted phosphorylation sites within the linker region for all four CaMKII genes, especially for longer linker variants (CaMKIIβ, γ, δ) (Jehl et al., 2016). Nuclear translocation enabled by the NLS in exon 15 is conditional on the phosphorylation state of adjacent serine residues, also contained in exon 15 (Brocke et al., 1995; Heist et al., 1998; Ma et al., 2014, 2015). The roles of many other linker phosphorylation sites remain unknown. Additionally, the linker contains sites predicted to be acetylated and ubiquitylated that have yet to be explored. Post-translational modifications within the linker region may facilitate structural changes, which in turn would have significant functional ramifications for intrinsic activity, interactions with other proteins, or changes in protein lifetime (Bah and Forman-Kay, 2016).

Structural implications of alternative splicing

There are two intriguing alternative splice sites outside the variable linker region. A splice site in exon 23 of CaMKIIβ can produce a short version of the hub domain with 26 residues removed (Wang et al., 2000). Deletion of these residues would require a significant structural rearrangement to maintain the fold of the hub domain (Fig. 1B). A recent study employed this short hub variant in cellular assays and showed that, impressively, it does appear to assemble into a mixed oligomer when expressed with wild-type CaMKIIβ (Cook et al., 2018). The other unique splice site is at exon 6 of the CaMKIIδ kinase domain. The CaMKIIδ gene encodes two versions of this exon, with one or the other, but never both, spliced into CaMKIIδ transcripts. The two resulting versions of CaMKIIδ kinase domain have not been studied to date, nor, to our knowledge, has this alternative splice cite been reported previously. The only record of the two versions of CaMKIIδ kinase domain appears to be in database entries for CaMKIIδ splice variants: for example, Consensus Coding Sequence Database (CCDS) identifiers CCDS3703, which contains exon 6v1, and CCDS82948, which contains exon 6v2. Further studies are necessary to interrogate the structural details of these variants, as well as their biological relevance.

CaMKII exchanges subunits in an activation-dependent manner to form mixed oligomers (Stratton et al., 2014; Bhattacharyya et al., 2016). It will be especially interesting to understand how the CaMKIIβ short hub variant affects subunit exchange properties (Stratton et al., 2014). To date, the linker identity has not been shown to significantly affect subunit exchange rates in CaMKIIα (Stratton et al., 2014). However, it will be important to test linker length differences in other CaMKII variants, as well as between CaMKII genes. CaMKIIα/β mixed oligomers are known to be abundant in the brain (Bennett et al., 1983; Kuret and Schulman, 1984; Miller and Kennedy, 1986), and it has been shown that CaMKIIα and β homo-oligomers undergo subunit exchange upon activation in vitro to form mixed oligomers (Bhattacharyya et al., 2016). Further experiments will be necessary to determine the effect of linker length/sequence on subunit exchange, and whether this could result in a specific population of mixed oligomers in specific cell types.

There are also clear effects of the linker composition on CaMKII structure. The kinases are physically attached to the hub domain through this variable linker, which is predicted to be intrinsically disordered. There have been many studies focused on understanding the structure of the holoenzyme, as well as the isolated hub and kinase domains (recently reviewed in (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019)). There is evidence from negative stain electron microscopy (EM) studies that the kinases extend far from the hub domain, presumably not interacting with the hub (Morris and Török, 2001; Myers et al., 2017). Alternatively, there is evidence from negative stain EM (Kolodziej et al., 2000), small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) and X-ray crystallography (Chao et al., 2011), and cryo-EM (Sloutsky et al., 2020) experiments that indicate that the kinase domains do directly interact with the hub domain. SAXS experiments revealed that CaMKIIα-0 (zero residue linker) holoenzymes have radii consistent with the conformation observed in the X-ray crystal structure of CaMKIIα-0 in which all kinases are docked onto the hub domain (Chao et al., 2011) (pdb: 3SOA). Cryo-EM reconstructions of CaMKIIα(15,18) showed evidence for this same docked conformation as well as an alternative docked conformation, discussed below (Sloutsky et al., 2020). Together, these data suggest that the kinases interact with the hub domain both in the absence of a linker and in the presence a 30-residue linker. This stands to reason – since these two domains have evolved together, it would be surprising had they not also evolved ways to interact (Kuriyan and Eisenberg, 2007). Future experiments are needed to further address the details of these specific interactions and their relevance to activity regulation and function.

To date, there is no structural information on the linker itself or how it may interact with the kinase or hub domains. Nonetheless, linker length and exon composition likely impact the dynamics within the holoenzyme structure. In the crystal structure of the CaMKIIα holoenzyme, the variable linker region is completely deleted (Chao et al., 2011). In cryo-EM reconstructions of CaMKIIα(14,18), the kinase domains adopted at least two different conformations in which the kinase directly interacts with the hub domain (Sloutsky et al., 2020). One was the same docked conformation as the one seen in the crystal structure, where the regulatory segment interacts with the hub domain (Chao et al., 2011) (PDB: 3SOA), while the other docked conformation showed the kinase C-lobe (helices αEF and αG) interacting with the hub domain. Further studies will be needed to determine the functional validity of these docked conformations.

Impact of linker on CaMKII activity regulation

Consistent with the kinase-docked conformation of CaMKIIα-0 in the crystal structure (Chao et al., 2011), the sensitivity of CaMKIIα to activation by Ca2+/CaM is correlated to the length of the variable linker. Purified CaMKIIα-0 requires significantly more Ca2+/CaM for activation compared to CaMKIIα(14,18) (30-residue linker) and CaMKIIα(14,15,18) (41-residue linker) (Sloutsky et al., 2020; Chao et al., 2011). However, this linker effect appears to be context-dependent, as variants of CaMKIIβ ranging in linker length from 217 to 0 residues are activated by the same concentration of Ca2+/CaM as CaMKIIα(14,18) and CaMKIIα(14,15,18). In addition, Bhattacharyya et al. (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020) recently reported that CaMKIIα(14,18) (30-residue linker) acquires Thr286 phosphorylation more readily than Thr305/306 phosphorylation, while the opposite is true for CaMKIIβ(13,14a,16,17,18,19,20,21) (217-residue linker). Together, these data suggest that linker length/sequence may also affect the balance of activation and inhibition of CaMKII.

Concluding remarks

The intricacies of CaMKII structure and function have been the focus of many studies for the past ~40 years. There have been significant strides toward understanding details of CaMKII structure, its downstream targets, and the enormous diversity of CaMKII variants produced from alternative splicing. However, many questions remain unanswered. Sequencing experiments have illuminated the diversity of CaMKII transcripts that exist in a single tissue, and this should be performed in all tissues where CaMKII is expressed. The levels of protein produced from these transcripts are currently unclear, which will be an important question to answer moving forward. Further understanding if and why so many CaMKII variants are necessary for function will be crucial to fully elucidating the role of this kinase in memory formation and other signaling roles. Finally, a key area of future study is to pursue the effect of linker post-translational modifications on CaMKII structure and function.

References

- Ahmad Z, DePaoli-Roach AA, and Roach PJ. Purification and characterization of a rabbit liver calmodulin-dependent protein kinase able to phosphorylate glycogen synthase. J Biol Chem, 257(14):8348–55, 7 1982. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs Johannes, Backs Thea, Neef Stefan, Kreusser Michael M., Lehmann Lorenz H., Patrick David M., Grueter Chad E., Qi Xiaoxia, Richardson James A., Hill Joseph A., Katus Hugo A., Bassel-Duby Rhonda, Maier Lars S., and Olson Eric N.. The delta isoform of cam kinase ii is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(7):2342–7, 2 2009. ISSN 1091–6490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bah Alaji and Julie D. Forman-Kay. Modulation of intrinsically disordered protein function by post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem, 291(13):6696–705, 3 2016. ISSN 1083–351X. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.695056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucum Anthony J., Shonesy Brian C., Rose Kristie L., and Colbran Roger J.. Quantitative proteomics analysis of camkii phosphorylation and the camkii interactome in the mouse forebrain. ACS Chem Neurosci, 6(4):615–31, 4 2015. ISSN 1948–7193. doi: 10.1021/cn500337u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer KU, Harbers K, and Schulman H. alphakap is an anchoring protein for a novel cam kinase ii isoform in skeletal muscle. EMBO J, 17(19):5598–605, 10 1998. ISSN 0261–4189. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer KU, Löhler J, Schulman H, and Harbers K. Developmental expression of the cam kinase ii isoforms: ubiquitous gamma- and delta-cam kinase ii are the early isoforms and most abundant in the developing nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 70(1):147–54, 6 1999. ISSN 0169–328X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MK and Kennedy MB. Deduced primary structure of the beta subunit of brain type ii ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase determined by molecular cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 84(7):1794–8, 4 1987. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MK, Erondu NE, and Kennedy MB. Purification and characterization of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase that is highly concentrated in brain. J Biol Chem, 258(20):12735–44, 10 1983. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Isackson PJ, Gall CM, and Jones EG. Differential effects of monocular deprivation on glutamic acid decarboxylase and type ii calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase gene expression in the adult monkey visual cortex. J Neurosci, 11(1):31–47, 1 1991. ISSN 0270–6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya Moitrayee, Stratton Margaret M., Going Catherine C., McSpadden Ethan D., Huang Yongjian, Susa Anna C., Elleman Anna, Cao Yumeng Melody, Pappireddi Nishant, Burkhardt Pawel, Gee Christine L., Barros Tiago, Schulman Howard, Williams Evan R., and Kuriyan John. Molecular mechanism of activation-triggered subunit exchange in ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. Elife, 5, 3 2016. ISSN 2050–084X. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya Moitrayee, Karandur Deepti, and Kuriyan John. Structural insights into the regulation of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii (camkii). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 10 2019. ISSN 1943–0264. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya Moitrayee, Lee Young Kwang, Muratcioglu Serena, Qiu Baiyu, Nyayapati Priya, Schulman Howard, Groves Jay T., and Kuriyan John. Flexible linkers in camkii control the balance between activating and inhibitory autophosphorylation. Elife, 9, 3 2020. ISSN 2050–084X. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DK, Takio K, Edelman AM, Charbonneau H, Titani K, Walsh KA, and Krebs EG. Identification of the calmodulin-binding domain of skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 82(10): 3187–91, 5 1985. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocke L, Srinivasan M, and Schulman H. Developmental and regional expression of multifunctional ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase isoforms in rat brain. J Neurosci, 15(10):6797–808, 10 1995. ISSN 0270–6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulleit RF, Bennett MK, Molloy SS, Hurley JB, and Kennedy MB. Conserved and variable regions in the subunits of brain type ii ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Neuron, 1(1):63–72, 3 1988. ISSN 0896–6273. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Heng-Yu Y., Minahan Kyra, Merriman Julie A., and Jones Keith T.. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase gamma 3 (camkiigamma3) mediates the cell cycle resumption of metaphase ii eggs in mouse. Development, 136 (24):4077–81, 12 2009. ISSN 1477–9129. doi: 10.1242/dev.042143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Luke H., Stratton Margaret M., Lee Il-Hyung H., Rosenberg Oren S., Levitz Joshua, Mandell Daniel J., Kortemme Tanja, Groves Jay T., Schulman Howard, and Kuriyan John. A mechanism for tunable autoinhibition in the structure of a human ca2+/calmodulin- dependent kinase ii holoenzyme. Cell, 146(5):732–45, 9 2011. ISSN 1097–4172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WY. Cyclic 3’,5’-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. demonstration of an activator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 38(3):533–8, 2 1970. ISSN 0006–291X. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WY. Cyclic 3’,5’-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. evidence for and properties of a protein activator. J Biol Chem, 246(9):2859–69, 5 1971. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WY. Calmodulin plays a pivotal role in cellular regulation. Science, 207(4426):19–27, 1 1980. ISSN 0036–8075. doi: 10.1126/science.6243188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Philip, Burchell Ann, Foulkes J. Gordon, Cohen Patricia T.W, Vanaman Thomas C., and Nairin Anagus C.. Identification of the ca2+dependent modulator protein as the fourth subunit of rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase kinase. FEBS Letters, 92(2):287–293, 8 1978. ISSN 1873–3468. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbran Roger J.. Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. Biochem J, 378(Pt 1):1–16, 2 2004. ISSN 1470–8728. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook Sarah G., Bourke Ashley M., O’Leary Heather, Zaegel Vincent, Lasda Erika, Mize-Berge Janna, Quillinan Nidia, Tucker Chandra L., Coultrap Steven J., Herson Paco S., and Bayer K. Ulrich. Analysis of the camkiiα and β splice-variant distribution among brain regions reveals isoform-specific differences in holoenzyme formation. Sci Rep, 8(1):5448, 4 2018. ISSN 2045–2322. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23779-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska R, Sherry JM, Aromatorio DK, and Hartshorne DJ. Modulator protein as a component of the myosin light chain kinase from chicken gizzard. Biochemistry, 17(2):253–8, 1 1978. ISSN 0006–2960. doi: 10.1021/bi00595a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman AM, Blumenthal DK, and Krebs EG. Protein serine/threonine kinases. Annu Rev Biochem, 56:567–613, 1987. ISSN 0066–4154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman CF and Schulman H. Identification and characterization of delta b-cam kinase and delta c-cam kinase from rat heart, two new multifunctional ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase isoforms. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1221 (1):89–101, 3 1994. ISSN 0006–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Ype, Fedorov Nikolai B., Ikonen Sami, Choi Esther S., Elgersma Minetta, Carvalho Ofelia M., Giese Karl Peter, and Silva Alcino J.. Inhibitory autophosphorylation of camkii controls psd association, plasticity, and learning. Neuron, 36(3):493–505, 10 2002. ISSN 0896–6273. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier Jessica, Lee Hoi Chang, Yassine Sandra, Zouari Raoudha, Martinez Guillaume, Karaouzène Thomas, Coutton Charles, Kherraf Zine-Eddine E., Halouani Lazhar, Triki Chema, Nef Serge, Thierry-Mieg Nicolas, Savinov Sergey N., Fissore Rafael, Ray Pierre F., and Arnoult Christophe. Homozygous mutation of plcz1 leads to defective human oocyte activation and infertility that is not rescued by the ww-binding protein pawp. Hum Mol Genet, 25(5): 878–91, 3 2016. ISSN 1460–2083. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K, Yamamoto H, Matsui K, Higashi K, and Miyamoto E. Purification and characterization of a ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from rat brain. J Neurochem, 39(6):1607–17, 12 1982. ISSN 0022–3042. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb07994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay Samudra S., Barber Amy L., Gallant Cynthia, Grabarek Zenon, Smith Janet L., and Morgan Kathleen G.. Differential functional properties of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase iigamma variants isolated from smooth muscle. Biochem J, 372(Pt 2):347–57, 6 2003. ISSN 0264–6021. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Jianjiong and Xu Dong. Correlation between posttranslational modification and intrinsic disorder in protein. Pac Symp Biocomput, pages 94–103, 2012. ISSN 2335–6936. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese KP, Fedorov NB, Filipkowski RK, and Silva AJ. Autophosphorylation at thr286 of the alpha calcium-calmodulin kinase ii in ltp and learning. Science, 279(5352):870–3, 2 1998. ISSN 0036–8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenring JR, Gonzalez B, McGuire JS, and DeLorenzo RJ. Purification and characterization of a calmodulin-dependent kinase from rat brain cytosol able to phosphorylate tubulin and microtubule-associated proteins. J Biol Chem, 258(20):12632–40, 10 1983. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley RM, Means AR, Ono T, Kemp BE, Burgin KE, Waxham N, and Kelly PT. Functional analysis of a complementary dna for the 50-kilodalton subunit of calmodulin kinase ii. Science, 237(4812):293–7, 7 1987. ISSN 0036–8075. doi: 10.1126/science.3037704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heist EK, Srinivasan M, and Schulman H. Phosphorylation at the nuclear localization signal of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii blocks its nuclear targeting. J Biol Chem, 273(31):19763–71, 7 1998. ISSN 0021–9258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring Bruce E. and Nicoll Roger A.. Long-term potentiation: From camkii to ampa receptor trafficking. Annu Rev Physiol, 78:351–65, 2016. ISSN 1545–1585. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch B, Meyer R, Hetzer R, Krause EG, and Karczewski P. Identification and expression of delta-isoforms of the multifunctional ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ Res, 84(6):713–21, 4 1999. ISSN 0009–7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incontro Salvatore, Díaz-Alonso Javier, Iafrati Jillian, Vieira Marta, Asensio Cedric S., Sohal Vikaas S., Roche Katherine W., Bender Kevin J., and Nicoll Roger A.. The camkii/nmda receptor complex controls hippocampal synaptic transmission by kinase-dependent and independent mechanisms. Nat Commun, 9(1):2069, 2018. ISSN 2041–1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04439-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa T, Fukunaga K, Yamamoto H, Tanaka E, and Miyamoto E. Ca2+, calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of glycogen synthase by a brain protein kinase. FEBS Lett, 161(1):28–32, 9 1983. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehl Peter, Manguy Jean, Shields Denis C., Higgins Desmond G., and Davey Norman E.. Proviz-a web-based visualization tool to investigate the functional and evolutionary features of protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res, 44 (W1):W11–5, 2016. ISSN 1362–4962. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi Shiro and Yamazaki Reiko. Calcium dependent phosphodiesterase activity and its activating factor (paf) from brain: Studies on cyclic 3,5-nucleotide phosphodiesterase (iii). Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 41(5):1104–1110, 12 1970. ISSN 0006–291X. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(70)90199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi Shiro, Yamazaki Reiko, and Nakajima Hisashi. Properties of a heat-stable phosphodiesterase activating factor isolated from brain extract studies on cyclic 3’, 5’-nucleotide phosphodiesterase. ii. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, 46(6):587–592, 1970. doi: 10.2183/pjab1945.46.587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karls U, Müller U, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, and Harbers K. Structure, expression, and chromosome location of the gene for the beta subunit of brain-specific ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii identified by transgene integration in an embryonic lethal mouse mutant. Mol Cell Biol, 12(8):3644–52, 8 1992. ISSN 0270–7306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PT, McGuinness TL, and Greengard P. Evidence that the major postsynaptic density protein is a component of a ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 81(3):945–9, 2 1984. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MB and Greengard P. Two calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases, which are highly concentrated in brain, phosphorylate protein i at distinct sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 78(2):1293–7, 2 1981. ISSN 0027–8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MB, McGuinness T, and Greengard P. A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from mammalian brain that phosphorylates synapsin i: partial purification and characterization. J Neurosci, 3(4):818–31, 4 1983. ISSN 0270–6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Shahid, Downing Kenneth H., and Molloy Justin E.. Architectural dynamics of camkii-actin networks. Biophys J, 116(1):104–119, 2019. ISSN 1542–0086. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej SJ, Hudmon A, Waxham MN, and Stoops JK. Three-dimensional reconstructions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent (cam) kinase iialpha and truncated cam kinase iialpha reveal a unique organization for its structural core and functional domains. J Biol Chem, 275(19):14354–9, 5 2000. ISSN 0021–9258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuret J and Schulman H. Purification and characterization of a ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from rat brain. Biochemistry, 23(23):5495–504, 11 1984. ISSN 0006–2960. doi: 10.1021/bi00318a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan John and Eisenberg David. The origin of protein interactions and allostery in colocalization. Nature, 450 (7172):983–990, 12 2007. ISSN 1476–4687. doi: 10.1038/nature06524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski AP and McGill JM. Human biliary epithelial cell line mz-cha-1 expresses new isoforms of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. Gastroenterology, 109(4):1316–23, 10 1995. ISSN 0016–5085. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski AP and McGill JM. Alternative splice variant of gamma-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii alters activation by calmodulin. Arch Biochem Biophys, 378(2):377–83, 6 2000. ISSN 0003–9861. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai YL, McGuinness TLM, and Greengard PG. Purification and characterization of brain ca2+ /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii that phosphorylates synapsin i, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CR, Kapiloff MS, Durgerian S, Tatemoto K, Russo AF, Hanson P, Schulman H, and Rosenfeld MG. Molecular cloning of a brain-specific calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 84 (16):5962–6, 8 1987. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas TJ, Burgess WH, Prendergast FG, Lau W, and Watterson DM. Calmodulin binding domains: characterization of a phosphorylation and calmodulin binding site from myosin light chain kinase. Biochemistry, 25(6): 1458–64, 3 1986. ISSN 0006–2960. doi: 10.1021/bi00354a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Huan, Groth Rachel D., Cohen Samuel M., Emery John F., Li Boxing, Hoedt Esthelle, Zhang Guoan, Neubert Thomas A., and Tsien Richard W.. ?camkii shuttles ca2+/cam to the nucleus to trigger creb phosphorylation and gene expression. Cell, 159(2):281–94, 10 2014. ISSN 1097–4172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Huan, Li Boxing, and Tsien Richard W.. Distinct roles of multiple isoforms of camkii in signaling to the nucleus. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1853(9):1953–7, 9 2015. ISSN 0006–3002. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier Lars S. and Bers Donald M.. Calcium, calmodulin, and calcium-calmodulin kinase ii: heartbeat to heartbeat and beyond. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 34(8):919–39, 8 2002. ISSN 0022–2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P, Möhlig M, Schatz H, and Pfeiffer A. New isoforms of multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. FEBS Lett, 333(3):315–8, 11 1993. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80678-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P, Möhlig M, Schatz H, and Pfeiffer A. Additional isoforms of multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in rat heart tissue. Biochem J, 298 Pt 3:757–8, 3 1994a. ISSN 0264–6021. doi: 10.1042/bj2980757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P, Möhlig M, Seidler U, Rochlitz H, Fährmann M, Schatz H, Hidaka H, and Pfeiffer A. Characterization of gamma- and delta-subunits of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in rat gastric mucosal cell populations. Biochem J, 297 (Pt 1):157–62, 1 1994b. ISSN 0264–6021. doi: 10.1042/bj2970157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer P, Möhlig M, Idlibe D, and Pfeiffer A. Novel and uncommon isoforms of the calcium sensing enzyme calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase ii in heart tissue. Basic Res Cardiol, 90(5):372–9, 1995. ISSN 0300–8428. doi: 10.1007/bf00788498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness TL, Lai Y, Greengard P, Woodgett JR, and Cohen P. A multifunctional calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. similarities between skeletal muscle glycogen synthase kinase and a brain synapsin i kinase. FEBS Lett, 163 (2):329–34, 11 1983a. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness TLM, Kelly PTK, Ouimet CCO, and Greengard PG. Studies on the subcellular and regional distribution of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in rat brain, 1983b. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SG and Kennedy MB. Distinct forebrain and cerebellar isozymes of type ii ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase associate differently with the postsynaptic density fraction. J Biol Chem, 260(15):9039–46, 7 1985. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SG and Kennedy MB. Regulation of brain type ii ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase by autophosphorylation: a ca2+-triggered molecular switch. Cell, 44(6):861–70, 3 1986. ISSN 0092–8674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EP and Török K. Oligomeric structure of alpha-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. J Mol Biol, 308(1): 1–8, 4 2001. ISSN 0022–2836. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Janette B., Zaegel Vincent, Coultrap Steven J., Miller Adam P., Bayer K. Ulrich, and Reichow Steve L.. The camkii holoenzyme structure in activation-competent conformations. Nat Commun, 8:15742, 6 2017. ISSN 2041–1723. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn AC and Greengard P. Purification and characterization of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase i from bovine brain. J Biol Chem, 262(15):7273–81, 5 1987. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn AC and Perry SV. Calmodulin and myosin light-chain kinase of rabbit fast skeletal muscle. Biochem J, 179 (1):89–97, 4 1979. ISSN 0264–6021. doi: 10.1042/bj1790089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn AC, Bhagat B, and Palfrey HC. Identification of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase iii and its major mr 100,000 substrate in mammalian tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 82(23):7939–43, 12 1985. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn AC and Greengard P. Widespread tissue distribution of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase i that phosphorylates synapsin 1, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn ACN and Greengard PG. Purification and characterization of brain ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase i that phosphorylates synapsin i, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nestler Eric J. and Greengard Paul. Protein phosphorylation in the nervous system. Wiley, 1984. ISBN 0471805580. [Google Scholar]

- Nghiem P, Saati SM, Martens CL, Gardner P, and Schulman H. Cloning and analysis of two new isoforms of multifunctional ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. expression in multiple human tissues. J Biol Chem, 268 (8):5471–9, 3 1993. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka N, Shiojiri M, Kadota S, Morinaga H, Kuwahara J, Arakawa T, Yamamoto S, and Yamauchi T. Gene of rat ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii alpha isoform – its cloning and whole structure. FEBS Lett, 396 (2–3):333–6, 11 1996. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary Heather, Lasda Erika, and Bayer K. Ulrich. Camkiibeta association with the actin cytoskeleton is regulated by alternative splicing. Mol Biol Cell, 17(11):4656–65, 11 2006. ISSN 1059–1524. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson NJ, Massé T, Suzuki T, Chen J, Alam D, and Kelly PT. Functional identification of the promoter for the gene encoding the alpha subunit of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 92 (5):1659–63, 2 1995. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey HC. Presence in many mammalian tissues of an identical major cytosolic substrate (mr 100 000) for calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett, 157(1):183–90, 6 1983. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)81142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne ME and Soderling TR. Calmodulin-dependent glycogen synthase kinase. J Biol Chem, 255(17):8054–6, 9 1980. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne ME, Schworer CM, and Soderling TR. Purification and characterization of rabbit liver calmodulin-dependent glycogen synthase kinase. J Biol Chem, 258(4):2376–82, 2 1983. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison AJ, Bass Martha A., Jiao Yuxia, MacMillan Leigh B., Carmody Leigh C., Bartlett Ryan K., and Colbran Roger J.. Multivalent interactions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii with the postsynaptic density proteins nr2b, densin-180, and alpha-actinin-2. J Biol Chem, 280(42):35329–36, 10 2005. ISSN 0021–9258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman H and Greengard P. Stimulation of brain membrane protein phosphorylation by calcium and an endogenous heat-stable protein. Nature, 271(5644):478–9, 2 1978a. ISSN 0028–0836. doi: 10.1038/271478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman H and Greengard P. Ca2+-dependent protein phosphorylation system in membranes from various tissues, and its activation by "calcium-dependent regulator". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 75(11):5432–6, 11 1978b. ISSN 0027–8424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer CM, McClure RW, and Soderling TR. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinases purified from rat brain and rabbit liver. Arch Biochem Biophys, 242(1):137–45, 10 1985. ISSN 0003–9861. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer CM, Rothblum LI, Thekkumkara TJ, and Singer HA. Identification of novel isoforms of the delta subunit of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. differential expression in rat brain and aorta. J Biol Chem, 268(19):14443–9, 7 1993. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenolikar S, Lickteig R, Hardie DG, Soderling TR, Hanley RM, and Kelly PT. Calmodulin-dependent multifunctional protein kinase. evidence for isoenzyme forms in mammalian tissues. Eur J Biochem, 161(3):739–47, 12 1986. ISSN 0014–2956. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenolikar Shirish, Cohen Patricia T. W., Cohen Philip, Nairn Angus C., and Perry S. Victor. The role of calmodulin in the structure and regulation of phosphorylase kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. European Journal of Biochemistry, 100(2):329–337, 10 1979. ISSN 1432–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb04175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer HA, Benscoter HA, and Schworer CM. Novel ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii gamma-subunit variants expressed in vascular smooth muscle, brain, and cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem, 272(14):9393–400, 4 1997. ISSN 0021–9258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloutsky Roman, Dziedzic Noelle, Dunn Matthew J., Bates Rachel M., Torres-Ocampo Ana P., Boopathy Sivakumar, Page Brendan, Weeks John G., Chao Luke H., and Stratton Margaret M.. Heterogeneity in human hippocampal camkii transcripts reveals allosteric hub-dependent regulation. bioRxiv, page 721589, 1 2020. doi: 10.1101/721589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton Margaret, Lee Il-Hyung H., Bhattacharyya Moitrayee, Christensen Sune M., Chao Luke H., Schulman Howard, Groves Jay T., and Kuriyan John. Activation-triggered subunit exchange between camkii holoenzymes facilitates the spread of kinase activity. Elife, 3:e01610, 1 2014. ISSN 2050–084X. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull James T., Nunnally Mary H., and Michnoff Carolyn H. 4 Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinases, volume 17, pages 113–166. Academic Press, 1 1986. doi: 10.1016/S1874-6047(08)60429-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Toru, Suzuki Emi, Yoshida Naoko, Kubo Atsuko, Li Hongmei, Okuda Erina, Amanai Manami, and Perry Anthony C. F.. Mouse emi2 as a distinctive regulatory hub in second meiotic metaphase. Development, 137(19):3281–91, 10 2010. ISSN 1477–9129. doi: 10.1242/dev.052480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M and Fujisawa H. New alternatively spliced variants of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii from rabbit liver. Gene, 221(1):107–15, 10 1998. ISSN 0378–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Yamamoto H, Matsumoto K, Kimura T, Katsuragi S, Miyakawa T, and Miyamoto E. Nuclear localization of the delta subunit of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in rat cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem, 72(2):815–25, 2 1999. ISSN 0022–3042. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Yamamoto H, Fukunaga K, Miyakawa T, and Miyamoto E. Identification of the isoforms of ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in rat astrocytes and their subcellular localization. J Neurochem, 74 (6):2557–67, 6 2000. ISSN 0022–3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobimatsu T and Fujisawa H. Tissue-specific expression of four types of rat calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii mrnas. J Biol Chem, 264(30):17907–12, 10 1989. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobimatsu T, Kameshita I, and Fujisawa H. Molecular cloning of the cdna encoding the third polypeptide (gamma) of brain calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. J Biol Chem, 263(31):16082–6, 11 1988. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombes RM and Krystal GW. Identification of novel human tumor cell-specific camk-ii variants. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1355(3):281–92, 3 1997. ISSN 0006–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombes Robert M., Faison M. Omar, and Turbeville JM. Organization and evolution of multifunctional ca(2+)/cam-dependent protein kinase genes. Gene, 322:17–31, 12 2003. ISSN 0378–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquidi V and Ashcroft SJ. A novel pancreatic beta-cell isoform of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii (beta 3 isoform) contains a proline-rich tandem repeat in the association domain. FEBS Lett, 358(1):23–6, 1 1995. ISSN 0014–5793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Wu YL, Zhou TH, Sun Y, and Pei G. Identification of alternative splicing variants of the beta subunit of human ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii with different activities. FEBS Lett, 475(2):107–10, 6 2000. ISSN 0014–5793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Xiaohan, Marks Christian R., Perfitt Tyler L., Nakagawa Terunaga, Lee Amy, Jacobson David A., and Colbran Roger J.. A novel mechanism for ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii targeting to l-type ca2+channels that initiates long-range signaling to the nucleus. J Biol Chem, 292(42):17324–17336, 2017. ISSN 1083–351X. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.788331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR, Tonks NK, and Cohen P. Identification of a calmodulin-dependent glycogen synthase kinase in rabbit skeletal muscle, distinct from phosphorylase kinase. FEBS Lett, 148(1):5–11, 11 1982. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)81231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR, Davison MT, and Cohen P. The calmodulin-dependent glycogen synthase kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. purification, subunit structure and substrate specificity. Eur J Biochem, 136(3):481–7, 11 1983. ISSN 0014–2956. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR, Cohen P, Yamauchi T, and Fujisawa H. Comparison of calmodulin-dependent glycogen synthase kinase from skeletal muscle and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-ii from brain. FEBS Lett, 170(1):49–54, 5 1984. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K, Yazawa M, Kakiuchi S, Ohshima M, and Uenishi K. Identification of an activator protein for myosin light chain kinase as the ca2+-dependent modulator protein. J Biol Chem, 253(5):1338–40, 3 1978. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T and Fujisawa H. Evidence for three distinct forms of calmodulin-dependent protein kinases from rat brain. FEBS Lett, 116(2):141–4, 7 1980. ISSN 0014–5793. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T and Fujisawa H. Purification and characterization of the brain calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (kinase ii), which is involved in the activation of tryptophan 5-monooxygenase. Eur J Biochem, 132(1):15–21, 4 1983. ISSN 0014–2956. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Nakata H, and Fujisawa H. A new activator protein that activates tryptophan 5-monooxygenase and tyrosine 3-monooxygenase in the presence of ca2+-, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. purification and characterization. J Biol Chem, 256(11):5404–9, 6 1981. ISSN 0021–9258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Takashi Y.and Fujisawa Hitoshi F.. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (kinase ii) which occurs only in the brain tissues. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 109(3):975–981, 12 1982. ISSN 0006–291X. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(82)92035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Sook-Young Y., Jellerette Teru, Salicioni Ana Maria, Lee Hoi Chang, Yoo Myung-Sik S., Coward Kevin, Parrington John, Grow Daniel, Cibelli Jose B., Visconti Pablo E., Mager Jesse, and Fissore Rafael A.. Human sperm devoid of plc, zeta 1 fail to induce ca(2+) release and are unable to initiate the first step of embryo development. J Clin Invest, 118(11):3671–81, 11 2008. ISSN 0021–9738. doi: 10.1172/JCI36942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZL and Ikebe M. New isoforms of ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in smooth muscle. Biochem J, 299 (Pt 2):489–95, 4 1994. ISSN 0264–6021. doi: 10.1042/bj2990489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]