Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic presents unprecedented challenges for the health care system. The pressure on health care staff continues to intensify, accentuated by the confinement (lockdown) of the population and the unprecedented duration of this emergency. Separately and especially together, overwork, degraded conditions of care because of the never-ending emergency, and the risk of exposure to the virus can lead to acute psychological distress or signs of burnout.

This original program was developed at Cochin Hospital in Paris, France to prevent these potentially dramatic psychological consequences, support the medical staff, and identify those most affected to offer them specific care. A program and a space for relaxation and support for hospital caregivers by hospital caregivers, the Port Royal Bulle (the Bubble) offers these workers help in decompression and relaxation. It combines a warm and caring welcome that promotes attention, listening, conversations, and exchanges as needed, empathetic support, and the ability to participate in soothing, relaxing, or low-impact physical activities. It takes care of caregivers. The Bubble is a program that is simple to set up and that appears to meet professionals' expectations. Making it permanent and enlarging its scale, as a complement to existing programs, might help to support health care personnel in their work.

Key Words: Psychosocial risks, health care workers, COVID-19 pandemic, work-related stress, professional burnout

Key Message

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic presents unprecedented challenges for the health care system. The pressure on health care staff, accentuated by the confinement (lockdown), can lead to acute psychological distress or signs of burnout. To support the medical staff and identify those most affected to offer them specific care, an original program was developed at Cochin Hospital in Paris: a space for relaxation and support for hospital caregivers by hospital caregivers.

Introduction

The pandemic of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) and its rapid international propagation have created unprecedented challenges to health care systems worldwide.1 The pressure on health care staff continues to intensify,2 accentuated by the confinement or lockdown of the population and the length of this crisis period. The prevention and management of the distress of workers subject to harsh stress in overburdened departments has become a major issue.

The principal factor of distress in today's hospitals is overwork, together with degraded conditions because of the emergency situation and the risk of exposure to the virus.2, 3, 4

The stress linked to the risk of infection is combined with workers' fears of endangering their own lives and the lives of their family, friends, and colleagues and can lead to acute psychological distress or signs of burnout.2 , 5, 6, 7 This stress is enhanced by the excess amount of work, social isolation, anger, frustration, the helplessness induced by the shortages of personal protective equipment and the lack of information,3 , 8 the sometimes repetitive changes in care policies,5 and still further by the increased workload because of colleagues unable to work because they have been infected by COVID-19.9

These professionals are exposed in emergency situations, intensively and without preparation, to suffering, recurrent deaths, and numerous ethical interrogations.10 An infectious disease specialist in Milan thus described his experience caring for patients with COVID-19: It's an impossible-to-understand situation, with people intubated in the hallway, not enough ventilators, ethical decisions about which patient to intubate. A shortage of masks and gloves, confusion and exhaustion. Hell is probably like this. I do not have the time to understand, to think about, or to express emotions.1

The COVID-19 epidemic engenders high levels of short-term stress and anxiety and exposes these workers to the risk of persistent stress exposure syndromes.3 These symptoms reduce their capacity to function effectively and can develop in the long term toward distress and burnout, post-traumatic stress syndrome, or other chronic mental conditions.5 Various teams in China and Europe have already observed a variety of symptoms: anxiety, stress, post-traumatic stress symptoms, moral injury, depression, sleep disorders, and functional somatic complaints.7 , 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 They are more frequent among women, nursing staff, and frontline professionals.11 , 16

It is essential to do a better job protecting medical staff against these psychological effects of the pandemic.1 , 3 , 9, 10, 11 , 17 Recommendations insist on preparatory team training,5 , 11 , 18 support by peers and the institution,17, 18, 19 supervision or Schwartz rounds,20 that is, a structured forum where the entire staff (clinical and nonclinical) of a department meet to discuss the emotional and social aspects of their work with facilitators who encourage them to adopt a reflexive attitude about the topics mentioned during a confidential speaking time. They also propose more concrete measures—the reorganization of tasks, improvement in the satisfaction of immediate daily needs (provision of food, rest breaks, decompression time, and adequate time off), and clear, concise, and measured communication.17 Signs of distress—with suffering expressed as sadness, anxiety, tiredness, hopelessness, insomnia, irritability, and intrusion symptoms, but also avoidance, that is, withdrawal and indifference—must be identified and supported toward individual, even specialized, mental health care.10 After the crisis period ends, the analysis and lessons from these extraordinarily difficult experiences must promote the expression of a meaningful rather than traumatizing narrative of what was experienced.

After China and Northern Italy, France became the third country to be severely affected by this epidemic. The first deaths were recorded at the beginning of March 2020, and a nationwide health emergency was declared. A slight delay after the epidemic onset in Italy benefited France, but the health care system was rapidly strained, and the controversy around the lack of personal protection equipment—masks especially—created a climate of stress and worry among health care professionals, already vulnerable after a social and budgetary crisis underway for more than a year.21 As the institution receiving the most severe cases, public hospitals had to manage a sharp rise in admissions of patients with serious symptoms of COVID-19 disease. One consequence was the rapid reorganization of care provision: transformation of rooms for patients with standard diseases (in the departments of internal medicine, gastroenterology, and pulmonary medicine) or recovery rooms into intensive care units (ICUs), creation of ICU beds in different departments (pediatrics, neurology, and maternity ward), seeking reinforcements from professionals and students, and emergency changes in job duties to the tasks most urgently needed. Crisis management groups in health care facilities rapidly recognized the strain on teams and the distress of frontline workers. At Cochin Hospital (APHP, Paris), the mobile psychological support team (the AVEC team: Dr. Lefèvre, Prof. Moro, and Prof. Granger) advocated completing the resources available by a space—physical and mental—devoted to the support and well-being of these health care workers (HCWs).

Description of the Program

La Bulle de Port Royal (The Port Royal Bubble) was created to meet these needs. The collective and synergistic mobilization of the administrative management teams and of medical and related or auxiliary workers (e.g., pediatricians, child and youth psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, physical therapists, athletic coaches and trainers, sophrologists [providers of therapy aimed at relaxation and harmony]) led to the opening of a space for support and well-being within the hospital, combining a place to talk and a place for physical movement.

Aim and Description of the Program

The lockdown of the entire population and the closing of the places people went before the pandemic for decompression, relaxation, and exercise intensified the psychological burden on teams: the physical, psychological, and emotional intensity of providing medical care have been aggravated by isolation, boredom, and the impossibility of relaxing with one's family, outdoors, with friends, and of exercising and spending time outside.4

The aim therefore was to offer staff a solution at the hospital to free them from this bind. The Port Royal Bubble fulfills this objective by offering a space that is outside the walls and outside time: the walls are those in the ICU, acute care rooms, and medical departments. Health care personnel need to be removed from the alarms for the heart rate monitors, saturometers, and automatic syringes, as well as from the complaints and anxieties expressed by patients or their families. The time was that before the epidemic, soothing, symbolized by the cloister and garden of the hospital chapel built by the Parisian abbey of Port Royal in the 17th century, and a symbol of resistance to plagues and other past disasters. The Bubble is located in the chapel cloister, an enclosed space on the hospital grounds, physically separate from the medical buildings and generally unavailable to the public.

The Port Royal Bubble is a space for relaxation, for support to hospital caregivers by hospital caregivers, offering activities to facilitate decompression and relaxation. It combines a warm caring welcome that promotes attention, listening, conversations, and exchanges as needed, empathetic support, and the ability to participate in comforting, relaxing, or low-impact physical activities. The objective is to soothe, relieve, and support staff members who have been overtaxed for several weeks to help them to hold on. The reception and conversation area also makes it possible to detect and support the workers in distress.

Organization, Space, and Activities

The Bubble is open seven days a week, without interruption, from nine in the morning to nine at night. Hospital employees can sign up for activities online or just come to the reception area to participate. The hours were designed to enable utilization by staff working any shift.

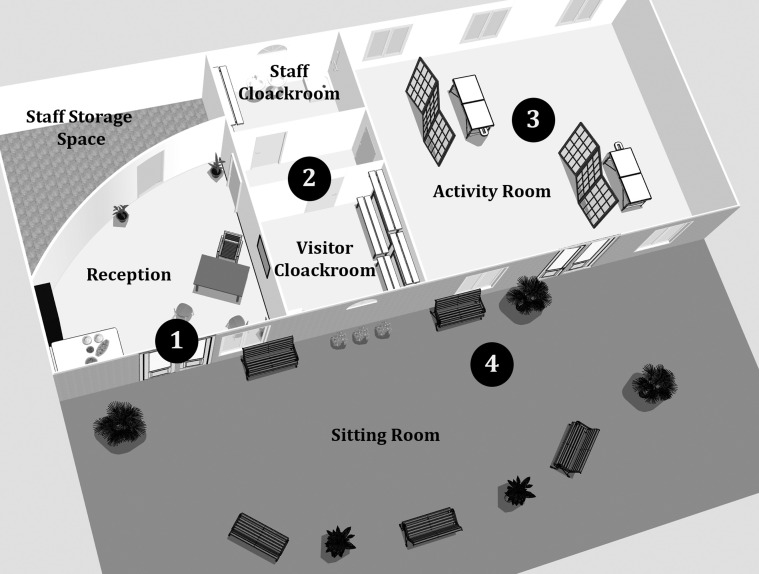

The program is organized around four specific areas, three rooms, and the garden (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Map of the Bubble. 1) Reception of health care workers, place for conversation and listening, and reminders of the hygiene requirements; 2) passage to the cloakroom, to leave belongings and wash hands; 3) modular room for relaxation and low-impact physical activities; and 4) a second opportunity to talk, be listened to, in the sitting room.

Space

Visitors signal their presence from the outside (covered cloister walkway) and wait there when the conversation space is full.

They are then welcomed in the 269-square-foot (25-m2) conversation space where administrative data are collected, and information about the activities is provided. An informal discussion about how they are feeling and what can be done to support them can start here. Music, drinks, and snacks from donations are offered. When too many visitors come at the same time, interviews may be organized outside in the covered cloister.

After passing through the cloakroom to wash their hands, the visitors are welcomed in the multipurpose activities room, where activities take place according to a schedule that changes daily (Table 1 ). All activities are booked online before the session.

Table 1.

Day's Agenda of the Activities (9:00 am–9:00 pm)

| Schedule | Activity | No. of Animators | No. of Visitors by Session | Total No. of People in the Room |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four times 20 minutes' sessions with 10 minutes' aeration | Massage therapy | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Four times 30 minutes' sessions with 15 minutes' aeration | Pilates or strength training | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Four times 20 minutes' sessions with 10 minutes' aeration | Sophrology—relaxation | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Four times 20 minutes' sessions with 10 minutes' aeration | Massage therapy | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Two times 45 minutes' sessions with 15 minutes' aeration | Shiatsu | 2 | 2 | 4 |

At the end of the activities, the visitors leave the room from a specific door. The Bubble staff may offer them another drink and an ear if desired.

Health Hygiene Protocol

A health hygiene protocol was of course established: surgical masks worn, regular disinfection, street clothes or clean uniforms, use of disposable material (gloves and massage sheets), social distancing of at least 2 m, with the space ventilated and aired regularly.

As these activities take place successively, the number of people in the multipurpose activity room nearly 600 square feet (55 m2) never exceeds five. Between each session, this room is aired out (for 10–15 minutes) by four large windows and a door giving onto the cloister. The door and windows of the reception area are always open. The rooms are cleaned and disinfected daily by the hospital cleaning staff.

Every piece of equipment used is disinfected with cleaning wipes or viricidal sprays after each use. The massage table sheets are single-use paper covers systematically replaced after each visitor.

The facilitators wear a surgical mask and disinfect their hands between each act or session. These materials are available in the multipurpose activity room.

The hospital workers arrive wearing a surgical mask, in clean uniforms or street clothes. Masks and alcohol-based disinfecting solution are available for them at the entry and exit from the Bubble, along with wastebaskets to dispose of the used material. The Bubble staff monitors compliance with the hygiene protocol.

Conversation Space

As an informal conversation space, the reception area for hospital staff visiting the Bubble aims to promote exchanges, including before or after an activity, around something to drink or eat (chocolates or fruit made available by gifts to the hospital). The Bubble staff handling reception tacitly express support, empathy, and recognition of the visitors' commitment and work. These staff members are also health care professionals: not only psychiatrists and psychologists but also pediatricians and social workers. This reception area is not somewhere to come for a psychological evaluation but rather for empathetic support expressed by peers.

Nonetheless, what these users recount, sometimes raw or hesitant, expresses distress that the Bubble staff can detect. More personalized listening can then be arranged and can lead to individual care in a confidential space outside the Bubble.

The reception area is thus a space of transition, an airlock if you will, that allows these HCWs to put down the burdens of their day and then benefit fully from some physical activity.

Physical Activity

For care of the physical pain reported by many, the Bubble offers individual massage therapy by physical therapists and sessions of Shiatsu—a massage technique of Japanese origin that uses touch to restore balance in the body. Each session lasts 20–45 minutes.

The low-impact physical activities combine sessions of Pilates—a method based on the concept of balancing the forces applied in the body by correcting muscle imbalance—with sessions of strength training and contactless boxing conducted by trained coaches for 30–45 minutes.

Finally, sessions of sophrology relaxation in groups of four are offered to help these staff members strengthen their individual capacity for stress management.

Results

At the end of its first four weeks, the Port Royal Bubble had recorded more than 800 staff visits (379 unique visitors, median of three visits/person). Two-thirds of the hospital employees who used the Bubble came from the five principal departments admitting patients with COVID-19: 25% from medical departments, including infectious diseases, pulmonary medicine, and gastroenterology; 25% from the emergency department; and 17% from ICUs. The remaining third came either from other departments of medical or surgical care or were technical and administrative staff, who are also highly overworked. In all, 34 staff people and facilitators provided services for these visitors.

Nurses accounted for 57% of the visitors, ahead of physicians (11%), technical (11%) and administrative staff (11%), and nurses' aides (10%). In all, 88% were women.

Visitors have been asked via electronic mail to tell us what they want from the Bubble, how it helps them, and how it could do better, in what we might describe as a free-text qualitative survey. These responses showed the HCWs' distress, sometimes raw: Psychologically, this period has been very trying. Many of us have been affected. I've seen colleagues break down in tears and crack psychologically in the break room or at the patient's bedside, talk about sleep disorders that prevent them from sleeping for more than an hour at a time … I have not been spared.

They describe the Bubble as a haven of silence, nature, and light, far from the disease and from worry; a priceless gift for the health care workers. They praise the availability, the listening, and the presence, the kindness and empathy of the welcome. One staff member explained that it's a place where we can check our care provider role, take this weight off our shoulders, and accept being for once and for a little while the person who is taken care of. Another specified that for the first time we have had the opportunity to take care of ourselves at our workplace. The well-being induced by the Bubble significantly improves our quality of life at work and boosts our productivity.

As the end of the lockdown appears and with it the return to some level of daily normality, many staff members are asking about the durability of the concept beyond this pandemic period. Some fear they will see this safe place, this space of rest and respite, disappear. For the workers, the Bubble helps with concerns much broader than the acute consequences of an exceptional epidemic situation—those of distress in the workplace: We can't forget that the difficulties encountered by healthcare workers do not stop with this pandemic and that the stress, the tensions, and difficulties encountered existed before and will continue after …

Discussion

All the risk factors for psychological suffering among medical workers identified in the literature are encompassed within the exceptional situation of the COVID-19 epidemic; they have been well described among health care providers working in critical care and among international humanitarian workers,22, 23, 24 in particular, the heavy workload as well as the lack of preparedness, training, and social support. In our results, the lower rate of visits from those working in the medical ICU may be explained by their better preparation for this stressful situation. The standard medical departments, on the other hand, had the most patient deaths,22 , 23 their staff had less training in emergencies, and their organization sometimes disintegrates in such situations. This may explain the higher rate of staff from these departments at the Bubble.

Immediate post-trauma management has been well described in the literature, and it is established that this support must be concrete, nonintrusive, and appropriate to the needs and expectations of the people to whom it is offered.25 The program at the Bubble is consistent with these international recommendations. It is also an original program because it is taking place during the trauma: the COVID-19 epidemic is not going to disappear soon, and the Bubble supports the HCW teams on a daily basis. The studies show that social support, and in particular peer support, limits the effect of exposure to trauma on stress symptoms8 , 26 and protects against the depression because of psychological distress and burnout.23 , 24 We have not found in the literature a description of a program offered during a period of trauma as complete as that offered by the Bubble.

The simultaneously natural and historic setting of the Bubble allowed us to theorize an outside-the-walls, outside-of-time concept, but it is not necessary for its functioning, as shown by the numerous replications of this program currently being tested in French hospitals. It is simple to set up and meets the expectations of hospital staff. In the future, an assessment of its medium-term effectiveness may enable it to be made permanent to complement existing programs. It is urgent to care for the physical and psychological conditions of health care workers. The integrity of the health care system and its ability to provide adequate care for its patients depend on them.

Limitations

This article is a descriptive short report. As our primary concern was to implement the program, we did not collect enough quantitative or qualitative data to evaluate it; this must be done in further work. In particular we could test the protective effect of coming to the Bubble against depression, burnout, and traumatic diseases.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all the facilitators (J. M. Aoun, C. Blaye, B. Bonvallet, P. Braquier, T. Chevallet, A. Gautier, B. Le Corre and AIST Cochin, H. J. Le Niger, J. Linières, H. Miqueu-Suhas, N. Noé, G. Pilon, L. Thiébot, E. Torre, M. Treillet, and A. Vaast), the psychological supervisors (F. Bordas Ponty, M. Fraile, E. Hengy, M. Mourouvaye, B. Samama, R. Simas, and K. Vella), and Jo Ann Cahn for the translation.

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu A.W., Connors C., Everly G.S., Jr. COVID-19: peer support and crisis communication Strategies to promote institutional resilience. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:822–823. doi: 10.7326/M20-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tam C.W.C., Pang E.P.F., Lam L.C.W., Chiu H.F.K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albott C.S., Wozniak J.R., McGlinch B.P., Wall M.H., Gold B.S., Vinogradov S. Battle buddies: rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress . CSTS, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University; Bethesda, USA: 2020. Sustaining the Well-Being of Healthcare Personnel During Infectious Disease Outbreaks. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maunder R., Lancee W., Balderson K. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerging Infect Dis. 2006;12:1924–1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu W., Zhang Y., Wang P. Psychological stress of medical staffs during outbreak of COVID-19 and adjustment strategy. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25914. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jmv.25914 Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W., Wang H., Lin Y., Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks S.K., Dunn R., Sage C.A.M., Amlôt R., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. Risk and resilience factors affecting the psychological wellbeing of individuals deployed in humanitarian relief roles after a disaster. J Ment Health. 2015;24:385–413. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1057334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ripp J., Peccoralo L., Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95:1136–1139. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohlken J., Schömig F., Lemke M.R., Pumberger M., Riedel-Heller S.G. COVID-19-Pandemie: Belastungen des medizinischen Personals: Ein kurzer aktueller review. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2020;47:190–197. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litz B.T., Stein N., Delaney E. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray E., Krahé C., Goodsman D. Are medical students in prehospital care at risk of moral injury? Emerg Med J. 2018;35:590–594. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2017-207216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williamson V., Stevelink S.A.M., Greenberg N. Occupational moral injury and mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212:339–346. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iversen A.C., Fear N.T., Ehlers A. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder among UK Armed Forces personnel. Psychol Med. 2008;38:511–522. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg N., Thomas S., Iversen A., Unwin C., Hull L., Wessely S. Do military peacekeepers want to talk about their experiences? Perceived psychological support of UK military peacekeepers on return from deployment. J Ment Health. 2003;12:565–573. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flanagan E., Chadwick R., Goodrich J., Ford C., Wickens R. Reflection for all healthcare staff: a national evaluation of Schwartz Rounds. J Interprofessional Care. 2020;34:140–142. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1636008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Guardian More than 600 French doctors threaten to quit amid funding row. the Guardian [Internet] 2019. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/16/600-french-doctors-threaten-to-quit-health-funding-row Available from.

- 22.Embriaco N., Papazian L., Kentish-Barnes N., Pochard F., Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:482–488. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quenot J.P., Rigaud J.P., Prin S. Suffering among carers working in critical care can be reduced by an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2413-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes Cardozo B., Gotway Crawford C., Eriksson C. Psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among international humanitarian aid workers: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization, War Trauma Foundation, World Vision International . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. Psychology first aid: guide for field workers [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ager A., Pasha E., Yu G., Duke T., Eriksson C., Cardozo B.L. Stress, mental health, and burnout in national humanitarian aid workers in Gulu, Northern Uganda: stress in national humanitarian workers in Uganda. J Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:713–720. doi: 10.1002/jts.21764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]