Abstract

Objectives

The DaR Global survey was conducted to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the intentions to fast and the outcomes of fasting in <18 years versus ≥18 years age groups with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).

Methods

Muslim people with T1DM were surveyed in 13 countries between June and August 2020, shortly after the end of Ramadan (23rd April–23rd May 2020) using a simple questionnaire.

Results

71.1% of muslims with T1DM fasted during Ramadan. Concerns about COVID-19 were higher in individuals ≥18 years (p = 0.002). The number of participants who decided not to fast plus those who received Ramadan-focused education were significantly higher in the ≥18-year group (p < 0.05). Hypoglycemia (60.7%) as well as hyperglycemia (44.8%) was major complications of fasting during Ramadan in both groups irrespective of age.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic had minor impact on the decision to fast Ramadan in T1DM cohort. This was higher in the age group of ≥18 years compared to those <18 years group. Only regional differences were noted for fasting attitude and behavior among T1DM groups. This survey highlights the need for Ramadan focused diabetes education to improve glucose control and prevent complications during fasting.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Type 1 diabetes, Ramadan, Survey

1. Introduction

People with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) are considered at increased risk for various complications during Ramadan, and most expert professional guidelines advise against undertaking the fast [1], [2]. Islamic authorities agree with medical experts to provide explicit exemptions from fasting for people with T1DM. Despite the clear exemptions from both medical and religious authorities being available, 43% of this population continues to fast during Ramadan [3]. Often, they do so without medical guidance putting themselves at risk for acute complications.

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) caused by coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is a global public health emergency that has so far led to over a million deaths worldwide [4]. Although safe fasting is possible during Ramadan through various measures (self-glucose monitoring, proper change in insulin doses, timing of insulin and Ramadan focused diabetes education), the COVID-19 pandemic represents an additional new concern for Muslim people with T1DM wishing to fast primarily because diabetes has emerged as a significant risk factor for adverse outcomes of COVID-19 infection [5], [6], [7], [8].

Guidance has suggested that people with T1DM should be actively discouraged from fasting during the COVID-19 pandemic; given the likelihood of encountering more adverse outcomes if they were to contract the illness. Indeed, people with diabetes are considered as the high-risk group for catching the new COVID-19 disease [9].

The practice of Ramadan Fasting among people with T1DM from North Africa, the UK, the Middle East, and other Asian countries is largely not understood. The last epidemiological study looking into a people with T1DM during Ramadan was in 2016 and included 136 patients [10]. Indeed, clinical studies have reported that with appropriate patient selection, many people with T1DM would be able to fast [11], [12]. Hence, this survey aims at looking into the behavior and attitudes of people with T1DM during Ramadan, to determine the outcomes of their fast, and whether the COVID-19 pandemic had any impact on their intentions to fast.

2. Methods

A total of 13 countries with a predominantly muslim population participated in the survey: Algeria, Bangladesh, Brunei, Egypt, India, KSA, Malaysia, Morocco, Pakistan, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE, and the UK. In each country, muslim people with diabetes were invited during their routine clinical consultation post-Ramadan to participate in the survey. People with T1DM were surveyed during 10 weeks between June and August 2020, shortly after the end of Ramadan (23rd April – 23rd May 2020). We here report on people with T1DM. The survey had the approval of the local research and ethics authorities. The criteria of inclusion were a diagnosis of T1DM and consenting to complete a brief questionnaire about their disease and Ramadan. People with T1DM were surveyed to determine whether the COVID-19 pandemic affected their decision to fast or not, distribution of days that were fasted at the end of Ramadan and after Ramadan, evaluate the risk of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia during Ramadan fasting, and to identify the level of education and SMBG in the management of diabetes during Ramadan using a questionnaire. They were asked about adverse events, including hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, attendance to accident and emergency, or admission to hospital. Hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose level of less than 70 mg/dl, and significant hyperglycemia as blood glucose level ≥300 mg/dl [13], [14]. Other information was provided by their doctors from the patient’s records. Differences in demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes between participants <18 years and ≥18 years old were tested using chi-squared analysis. All applied statistical tests were two-sided, p-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. No adjustment or weighted for comparisons was made. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 26.

3. Results

A total of 1483 people agreed to participate in the survey. Of these, 1054 (71.1%) intended to fast, and 792 (53.5%) were females. 60.2% of those who fasted were from KSA, 15.1% from Egypt, 7.1% from UAE, 4.3% from Pakistan, 3.2% from Malaysia, 2.1% from UK, 1.7% from Algeria, 1.7% from Morocco, 0.8% from Turkey and 3.9% from others (Bangladesh, Brunei, India and Tunisia). Majority of participants (88.2%) were on basal-bolus therapy, and 6.9% were treated with the insulin pump and 4.9% participants were treated with mixed insulin regimens. There were few notable differences in characteristics of patients who intended to fast among those aged<18 years, compared to those aged 18 years or more (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study population, according to age.

| Characteristics of the study population | <18 Years | ≥18 years | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants, n (%) | 370 (25%) | 1113 (75%) | 0.000 |

| Participants fasted, n (%) | 279 (26.8%) | 761 (73.2%) | 0.000 |

| Mean Age (Years); Mean ± SD | 14.5 ± 2.5 | 28.2 ± 9.0 | 0.000 |

| Male (%) | 168 (45.4%) | 525 (47.1%) | 0.461 |

| Female (%) | 202 (54.6%) | 590 (52.9%) | |

| Duration of diabetes (Years); Mean ± SD | 6.2 ± 4.01 | 11.8 ± 7.00 | 0.000 |

| HbA1c (%); Mean ± SD | 9.5 ± 2.00 | 8.5 ± 1.80 | 0.000 |

| Treatment regimens; n (%) | |||

| Basal Bolus Pump Mix insulin |

256 (93.8%) 13 (4.8%) 4 (1.5%) |

40 (84.9%) 71 (9.4%) 43 (5.7%) |

0.004 |

| Co-morbidities; n (%) | |||

| Hypertension Hyperlipidemia Retinopathy Neuropathy Nephropathy CAD, Stroke Foot problems with diabetes |

3 (0.8%) 5 (1.4%) 11 (3.0%) 16 (4.3%) 18 (4.9%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.2%) |

87 (7.8%) 125 (11.2%) 139 (12.5%) 105 (9.4%) 100 (9.0%) 12 (1.1%) 21 (1.9%) |

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.001 0.006 0.045 0.026 |

*HbA1c, Glycated hemoglobin; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease.

3.1. Intentions and abilities to fast

Of 1054 people intended to fast, 26.5% belong to <18 years age group and 73.5% to ≥18 years age group. The fasting decision varied widely among the countries. Fig. S1, in country-wise analysis, shows the percentage of people with T1DM fasting in Ramadan ranged from 13% in Turkey to 85% in Malaysia and 90% in KSA.

Age-wise comparison (<18 years vs. ≥18 years) of people with T1DM who were intending to fast or not showed significant difference. Overall, 71.1% (n = 1054) of the participants (75.4% of <18 years and 69.6% of ≥18 years), surveyed, reported their intention to fast. However, 26.8% managed to fast the full month; and 45%, 16.3%, 6.1%, and 5.9% could fast 22–29 days, 15–21 days, 8–14 days, and 1–7 days respectively. 59.9% and 59.1% of <18 years and ≥18 years of age broke their fast due to diabetes-related illnesses (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Survey Questionnaire and responses.

| Questions | <18 Years | ≥18 Years | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many days did you manage to fast this year? | 22.4 ± 8.0 | 23.8 ± 7.6 | 0.011 | |

| Did you intend to fast Ramadan this year? | Yes | 279 (75.4%) | 775 (69.6%) | 0.000 |

| No | 91 (24.6%) | 338 (30.4%) | ||

| Did you fast any days after Ramadan (Shawal)? | Yes | 41 (14.7%) | 164 (21.2%) | 0.043 |

| No | 238 (85.3%) | 609 (78.8%) | ||

| If yes, please specify number | 6.6 ± 2.9 | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 0.603 | |

| Did the COVID-19 epidemic affect your decision re-fasting Ramadan? | Yes | 1 (0.4%) | 43 (5.5%) | 0.002 |

| No | 267 (95.7%) | 709 (91.5%) | ||

| Not sure | 11 (3.9%) | 21 (2.7%) | ||

| Did you break your fast because of diabetes related illness? | Yes | 167 (59.9%) | 456 (59.1%) | 0.567 |

| If yes, please specify the days? | 7.8 ± 6.7 | 6.7 ± 7.0 | 0.100 | |

| Did you have any day-time hypoglycemia during this Ramadan? | Yes | 155 (55.6%) | 485 (62.6%) | 0.095 |

| If yes, please specify the days? | 6.2 ± 5.9 | 5.2 ± 5.3 | 0.040 | |

| Did you break your fast during this Ramadan because of hypoglycemia? | Yes | 133 (85.8%) | 410 (85.1%) | 0.147 |

| Did you need to attend emergency department or got admitted to hospital because of hypoglycemia during this Ramadan? | Yes, attended emergency department | 5 (3.2%) | 21 (4.4%) | 0.096 |

| Yes, admitted to hospital | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.5%) | ||

| If admitted, please specify days | 0.0 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.491 | |

| Did you have any day-time hyperglycemia during this Ramadan? | Yes | 126 (45.3%) | 345 (44.6%) | 0.735 |

| If yes on How Many Days? | 8.5 ± 6.8 | 7.5 ± 6.2 | 0.154 | |

| Did you break your fast during this Ramadan because of hyperglycemia (BG > 300 mg/dl)? | Yes | 74 (58.7%) | 255 (74.3%) | 0.004 |

| Did you need to attend emergency department or got admitted to hospital because of hyperglycemia during this Ramadan? | Yes, attended emergency department | 8 (6.3%) | 16 (1.7%) | 0.076 |

| Yes, admitted to hospital | 4 (3.1%) | 11 (3.2%) | ||

| If admitted, please specify days | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 0.086 | |

| Did you do SMBG during Ramadan? | Yes, same as before | 198 (71.2%) | 454 (59.0%) | 0.004 |

| Yes, at less frequency than before Ramadan | 9 (3.2%) | 50 (6.5%) | ||

| Yes, at less frequency than before Ramadan | 65 (23.4%) | 229 (29.7%) | ||

| No | 6 (2.2%) | 37 (4.8%) | ||

| Did you receive any education specific for Ramadan fasting? | Yes | 141 (50.7%) | 490 (63.3%) | 0.004 |

| No | 137 (49.3%) | 281 (36.4%) | ||

3.2. Impact of COVID-19

On questioning the participants with T1DM about whether the COVID-19 pandemic had influenced their choice on whether or not to fast, significant difference was found for the response to this question, between patients aged <18 and 18 years or more. In this survey, 0.4% (1/279) of <18 years and 5.5% (43/775) of ≥18 years participants said it had influenced their decision not to fast (Table 2).

4. Rates of hypoglycemia and participants response during Ramadan fasting

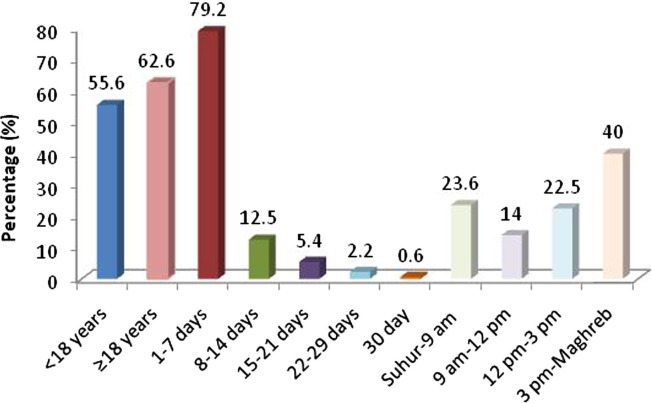

A total of 640 (60.7%) participants reported hypoglycemia. Rates of daytime hypoglycemia were 55.6% in those <18 years and 62.6% in those ≥18 years, however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.096) (Fig. 1 ). Of 640 participants, 79.2% experienced it between 1 and 7 days, 12.5% between 8 and 14 days, 5.4% between 15 and 21 days, 2.2% between 22 and 29 days, and 0.6% on 30th day. The majority of hypoglycemic episodes were encountered between 3 pm and Maghreb (sunset) time (40%), followed by between Suhur (predawn meal) and 9 am (23.6%), then between 12 pm and 3 pm (22.5%), and the least between 9 am and 12 pm (14%) as shown in Fig. 1. There was an impact of age on the average days of hypoglycemia, as participants aged <18 years had hypoglycemia on 6.2 ± 5.9 days compared to 5.2 ± 5.3 days for participants of 18 years or more (p = 0.040).

Fig. 1.

Rate, frequency and timing of hypoglycemia during Ramadan fasting.

The replies to the questions related to the impact of the occurrence of hypoglycemia on participant's behavior (<18 years vs. ≥18 years) are presented in Fig. S2. By far the most frequent response was an increase in the frequency of monitoring (13.7% vs. 14.1%) and the stoppage of Ramadan fast (12.7% vs. 13.9%). However, nearly 10% of participants did nothing but 9% of participants aged <18 years and only 2% aged ≥18 years omitted the medications and continued fasting (Fig. S2). The breaking of the fast was reported by nearly 85% of those with hypoglycemia. Of note, 33 participants needed to attend emergency services and/or hospital admission due to daytime hypoglycemia during Ramadan fasting. The difference between the two age groups was not statistically significant (emergency departments, 3.2% vs. 4.4% and hospital admission, 0 vs. 1.4%; p = 0.096).

4.1. Rates of hyperglycemia and participants response during Ramadan fasting

A total of 471 (44.8%) participants reported hyperglycemia. Rates of hyperglycemia were 45.3% in those <18 years and 44.6% in those ≥18 years (p = 0.735) (Fig. S3). Of these, 62.7% experienced it between 1 and 7 days, 23.2% between 8 and 14 days, 9.1% between 15 and 21 days, 3.0% between 22 and 29 days, and 1.9% on 30 days. The reported incidence of hyperglycemia was 45% during eating hours, 26% during fasting hours, and 29% during both eating and fasting hours (Fig. S3). There was no impact of age on the risk of hyperglycemia. No significant difference was found in the duration of hyperglycemia occurrence during Ramadan fasting between participants aged <18 years and 18 years or more age (8.5 ± 6.8 days vs. 7.5 ± 6.2 days; p = 0.154) as shown in Table 2.

The replies to the questions related to the impact of the occurrence of hyperglycemia on participant's behavior (<18 years vs. ≥18 years) are presented in Figure S4. By far the most frequent response was an increase in the dose of medication (35.1% vs. 32.8%) and cut down the food (16.7% vs. 13.0%). However, nearly 10% of participants under 18 years of age and 5% of participants aged 18 years or more did nothing (Fig. S4). There was a significant impact of age on the breaking of the fast due to hyperglycemia (58.7% for <18 years vs. 74.3% for ≥18 years). Recourse to emergency services was pursued by 39 participants with hyperglycemia (emergency departments, 8 (6.3%) vs. 16 (1.7%) and hospital admission, 4 (3.1%) vs. 11 (3.2%); p = 0.076).

4.2. Self-monitoring of blood glucose and education

Among the participants who fasted in Ramadan, more than half received Ramadan-focused education (60.0%). Participants with ≥18 years of age received Ramadan-focused education more frequently compared to participants with <18 years of age (p = 0.004). Of these participants, 52.6% reported receiving structured education from their doctor about diabetes management during Ramadan, followed by a dietician (20.9%), nurses (9.9%), and others (20.9%). On asking the question about the method of education, more than half of the participants (51.7%) stated that they received Ramadan-focused education from their doctors during a routine consultation. However, 23.8% received it through online apps, 13.5% through leaflets, and 11.0% through group sessions, respectively.

>60% (62.2%) of participants checked the blood glucose at the same frequency as before Ramadan fast (Table 2). Of the total 1054 participants, 59.3% monitored their blood glucose level 3–4 times daily and 18.9% twice daily, 9.2% once daily, and 5.8% two-four times daily. Of the participants, 3.4% tested their blood glucose once weekly, and 3.4% tested their blood glucose even less than once a week.

5. Discussion

Fasting during Ramadan is not merely abstinence from eating but involves a drastic change in lifestyle aspects and habits. Addressing these lifestyle changes is essential and challenging in people with T1DM. The DaR Global survey, a population-based survey conducted among 13 countries, most of them with a Muslim majority population, showed that 71.1% of participants with T1DM fasted during Ramadan, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. KSA had the highest number of participants who chose to fast. Compared with participants aged <18 years, a significantly larger number of participants aged ≥18 years decided not to fast during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were significant complications of fasting during Ramadan irrespective of age.

Over the last twenty years it seems that there’s been a significant increase in fasting prevalence among people with T1DM. The Epidemiology of Diabetes and Ramadan (EPIDIAR) study, which was conducted in 2001, found that as many as 42.8% people with T1DM reported fasting for at least 15 days during Ramadan [3]. However, the DAR-MENA T1DM study showed that despite the risk of various complications associated with fasting in people with T1DM (n = 138), 72.3% fasted for at least 15 days, and 48.5% fasted for the entire month of Ramadan [10]. The DaR Global survey found fasting in 71.1% of participants with T1DM during Ramadan. Fig. S3 shows that 29% of participants with T1DM decided not to fast, which is similar to DAR-MENA T1DM study [10]. However, the present survey also shows a pattern of high rates of fasting for the whole month (26.5%) or most of the month as 44.4% fasted 22–29 days. About 62% participants with T1DM (64% for the <18 years and 61% for those 18 or older) fasted for at least 15 days in this survey. Several studies indicated that some people with T1DM, including many adolescents, can fast when empowered with the appropriate patient education, blood glucose monitoring, insulin dose adjustment, and support by experts in the field, which collectively can lead to safer fasting during Ramadan [12], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

The potential risks associated with fasting in patients with T1DM are a disruption in glycemic control revealing as hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and metabolic emergencies [1]. Several studies have found that the incidence of severe hypoglycemia was negligible in people with T1DM during Ramadan fasting [19], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. The frequency, timing, and severity of hypoglycemia were elucidated in this survey where 55.6% of <18 years and 62.6% of ≥18 years had experienced at least an episode of hypoglycemia in a month. While 79.2% of these episodes occurred over 1–7 days during Ramadan fasting, 20.8% occurred at a high frequency extending from 8 to 30 days indicates the need to stress upon stopping the fast for those individuals with frequent hypoglycemia.

Most of hypoglycemic episodes were encountered between 3 pm and Maghreb time (40%), followed by between Suhur and 9 am (23.6%), then between 12 pm and 3 pm (22.5%), and the least between 9 am and 12 pm (14%). This indicates that hypoglycemia during Ramadan, occurs at all times of the day with the highest time during the period extending from mid-day to sunset time [12], [21].

The most frequent response to hypoglycemia was an increase in the frequency of monitoring and breaking of the fast followed by changes in dose or frequency of insulin. The DaR Global survey also shows a significant impact of age on the breaking of the fast due to hyperglycemia (58.7% in <18 years vs. 74.3% in ≥18 years). While 640 people with T1DM experienced at least one episode of hypoglycemia, 33 (5.15%) participants were required to attend emergency services and/or hospitalization. It is not clear how many hypoglycemic episodes required non-medical assistance as this was not asked in the questionnaire. Attending the emergency department or hospitalization during COVID-19 era with the lockdown measures and the possibility to be exposed to ER departments busy with COVID-19 patients could have impacted the decisions of many and perhaps opted to home management of hypoglycemia. Alternatively, this could reflect lower rates of severe hypoglycemia compared to 20 years ago and reflects the advances in T1DM management and the better understanding of fasting Ramadan as other studies also reported in recent years low rates of emergency department attendance or hospitalization for diabetes during Ramadan [28], [29].

Much of the focus during Ramadan is related to hypoglycemia, however, the EPIDIAR study has shown a significant increase in the rate of hospitalization during Ramadan for severe hyperglycemia (with or without ketoacidosis) among those with T1DM, from 5 to 16 events/100 people/month (p = 0.1635) [1]. In this DaR Global survey, 44.8% (471/1052) participants reported hyperglycemia and this occurred with no significant difference in the participants aged <18 years and ≥18 years. Recourse to emergency services was pursued by 39 (8.2%) participants with hyperglycemia which is more than those requiring this level of service due to hypoglycemia. This may be explained by the high HbA1c levels of the study cohort at baseline (9.4 ± 2.0% for the <18 years age group and 8.5 ± 1.8% for those ≥18 years).

The role of structured education in reducing the complications of diabetes is well established, and guidelines state that this structured education should be extended to Ramadan-focused education programs so that people with diabetes can make informed decisions [1], [2]. In DaR Global survey, only 60.2% of participants had access to diabetes education, of whom only 50.7% (141/278) participants aged <18 years received educational sessions compared to 63.6% (490/771) participants aged ≥18 years. Considering that Ramadan-focused diabetes education program can enable people with diabetes to reduce their risk of illness during fasts, the present survey showed that structured education is an essential strategy in diabetes management that was not optimally accessed by most participants. Of concern, some participants in the survey reported fasting despite not doing any blood glucose monitoring. A prospective study in type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients showed that active glucose monitoring, adjustment of medications; dietary counseling, and patient education significantly reduced the risk of acute complications with diabetes in fasting patients [30]. It is important for Ramadan structured education program to include healthcare professionals as a study in Pakistan found that almost one-third of general practitioners lacked knowledge of basic principles needed [31].

While some of data of this survey could be influenced with COVID-19 impact that was not the case for most of the responders. Indeed, this is the largest survey on T1DM during Ramadan over the last 19 years. Table 3 summarizes some of the key parameters of those who fasted. Clearly, the results confirm that while a sizeable proportion can fast with no safety concerns, many are not and certainly an array of measures are required to improve the safety for those who opt to fast.

Table 3.

Key parameters in people with T1DM who fasted Ramadan.

| (n = 1054, 71% of survey population) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting (Days) | 26.8% fasted for full 30 days | 45% fasted 22–29 days due to diabetes related illness | 28.2% fasted 21 days or less due to diabetes related illness |

| Hypoglycemia (%) | 39.3% reported no symptoms of hypoglycemia | 48% reported symptoms of hypoglycaemia over 1–7 days | 12.8% reported symptoms of hypoglycaemia over 8–30 days |

| Hyperglycemia (%) | 55.2% reported no episodes of hyperglycemia (BG > 300 mg/dl) |

28% had hyperglycemia over 1–7 days | 16.8% had hyperglycemia over 8–30 days |

| ER or hospital admission (%) | 93.2% did not require ER or hospital admission for hypo/hyperglycemia |

6.8% required ER or hospital admission for hypo/hyperglycemia |

|

This survey has some noteworthy limitations. Hypoglycemia was reported as symptomatic rather than confirmed and consequently higher rates of hypoglycemia are reported here. Data were captured by the recollection of events within living memory of a few weeks. However, medical and social events like hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia and breaking of the fast cannot be forgotten readily especially in Ramadan as the person needs to compensate for days not fasted. The use of several sites reflects practices in more extensive geographical regions; however, this may introduce confounders based on the differences of the social backgrounds and the different patterns of medical practice, prescribing habits and believes between regions. Finally, the survey cohort includes over 52% from the Gulf region or UK where medical facilities are of high standards or through experienced physicians in many other countries. Hence, the results of the survey could not be easily generalized to all people with T1DM.

In conclusion, COVID-19 pandemic had minor impact on the decision to fast Ramadan in T1DM cohort. This was higher in the age group of ≥18 years compared to those <18 years group. The fasting attitude and behavior were not largely different between the young and the adults, however, regional differences were noted. This survey highlights the need for Ramadan focused diabetes education to improve glucose control and prevent complications during fasting.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the people with TID who participated in this survey. The authors acknowledge WorkSure India for medical writing assistance and all the following investigators for their contributions and support towards the DaR Global survey data collection:

Rafhati, Teh Roseleen Nadia Roslan, Abada Djihed, Abdulaziz F. Alfadhly, Abeer Theyab, Achmad Rudijanto, Adem Cakir, Adibah Salleh, Adnan rayes, Ahallat, Ahmad Alkhatib, Ahmane Kamel, Ahmef Al Nahari, Aicha Ahmed, Aisha Elkhuzaimy, Alfadhli, Ali Alghamdi, Alice Yong, Alilouch, Allshenqete, Amal, Amira Ahmed Mahmoud, Amna Hassan, Ashraf, Asloum Zineb, Azarai, Azraai Nasruddin, Azriouil Manal, Bandar Damanhori, Barakatun Nisak Mohd Yusof, Bashir Tarzi, Belkadi Mounia, Belkhadir Jamal, Ben Salah Sourour, Benabed, Benabed Kebira, Benaiche Boucif, Bendjelloul, Benomar, Berchi Abdelkahar, Berra, Bidel Habiba, Bouab, Boudiaf Brahim, Boudiaf Kaouther, Bougaa Farouk, Boukadoum Affaf, Boutheina Mohamed Ali, Bouyoucef, Burhan Ates, Carolina Shalini, Chai Shu Teng, Chan Pei Lin, Chana, Chenouf Ismahen, Chikoiche Ilhem, Chooi Kheng Chiew, Chouadra Imene, Christine Shamala Selvaraj, Dalal Alromaihi, Diaddine Bouab, Diappo, Djouima Mounir, Echchad Lamya, El Moatamid Kaoutar, El Moatamid Mohammed, Elguermai Med Najib, Elliyyin Katiman, Elsheikh Farah Mohamed Elhassan, Eman Sheshah, Ercan Ozdemir, Fadel Ahmed El Amine, Farah Kamel, Faraoun Khadra, Fawaz Turkistani, Fatheya F Alawadi, Foo Siew Hui, Gökhan Uygun, Ghofran Khogeer, Gradi Nadia, Guebli, Guedmane Lamia, Guerboub Ahmed Anas, Guerra Yasmine, Guissi Loubna, Gunavathy Muthusamy, Haïti Nafia, Hadri Nadia, Hamda, Hamid Ashraf, Hamimah Saad, Hammouti Ihsan, Hanan Ali, Hanan Khanji, Haryati Hamzah, Havva Keskin, Herbadji, Hilal Mohammed Hilal, Hinde Iraqi, Hossam Hosny, Hui Chin Wong, Inass Shaltout, Jeyakantha Ratnasingam, Juani, Kamel Hemida Rohoma, Karoun, Ketata Mourad, Khadija Abdullah Mohammed, Khadija Hafidh, Khaled Baagar, Khaoula Gorgi, Khentout Imed Eddine, Khitas Abdelmoulmene, Kughanishah, Laghmassi Farid, Layla, Lee Wai Khew, Leena Swaidan, Lhassani Hamdoun, Lobna F. El Toony, Lobna Kammoun Kacem, Lounnas Nouara, Luay Qunash, Lutfi Lutfi Baran, Maha Abdelrazig Mohamed Maha Rajab, Majd Aldeen Kallash, Majid Alabbood, Malek, Mallem Noureddine, Manahel Alansary, Manal Hasan Twair, Manal Khorsheed, Mansour Alharbi, Mansour Alharbi, Mashaer Omar, Masliza Hanuni Mohd Ali, Masni Mohamad, Mastura, Maxima Shegem, Md Fariduddin, Mehmet Baştemir, Merzouki Fadhila, Mesbah Kamel, Messelem Fateh, Mhamdi Zineb, Miza Hiryanti, Mohamad 'Ariff Fahmi, Mohamed Bachiri, Mohamed Benlassoued, Mohamed Hassan Hatahet, Mohamed Hassanein, Mohammed Ali Batais, Mohammed Badedi, Mohammed Basher, Mohan T Shenoy, Mokri, Mujgan Gurler, Munirah Mohd Basar, Muris Barham, Mustafa Kanat, Nadeema Shuqom, Nancy Elbarbary, Naveed Alzaman, Nesrin Mohamed Labib, Ng Ooi Chuan, Nina Matali, Noor Rafhati Adyani, Nor Shaffinaz Yusoff Azmi, Nora Chabane, Norlela Sukor, Nouf Alamoudi, Noufel Ali, Nouti Nassim, Nurain, Nurain Mohd Noor, Oulebsir, Parag Shah, Qarni, Radjah Aicha, Rahman, Raja Nurazni, Rakesh Kumar Sahay, Reem Alamoudi, Rhandi Jamila, Rifai Kaoutar, Rizawati Ramli, Roda Abadeh, Rohayah, Saadoune Warda, Sabbar, Salah, Salma Mohd Mbarak, Sangeeta Sharma, SayaSri Wahyu, See Chee Keong, Seham Alzahrani, Serdal Kanuncu, Shabeen Naz Masood, Shahd Anani, Shanty Velaiutham, Shartiyah Ismail, Shehla Shaikh, Sri Wahyu Taher, Suaad Ahmed, Subhodip Pramanik, Sumaeya Abdulla, Susan Jacob, Tahseen Chowdhury, Talbi Alaa Eddine, Tamene, Tarek, Tarik Elhad, Teen Alamoudi, Teh Roseleen Nadia, Terchak, Tong Chin Voon, Toulali, Tounsi, Vijiya Mala, Walid Kaplan, Wan Juani, Wan Mohd Izani Wan Mohamed, Wong Hui Chin, Wong Hui Chin, Yakoob Ahmedani, Yusniza Yusoff, Z. Asloum, Z. Degha, Zainab, Zaiton Yahaya, Zanariah Hussein, Zineb Habbadi, and Zohra Degha.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108626.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Al-Arouj M., Assaad-Khalil S., Buse J., Fahdil I., Fahmy M., Hafez S., et al. Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan: update 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1895–1902. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassanein M., Al-Arouj M., Hamdy O., Bebakar W.M.W., Jabbar A., Al-Madani A., et al. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical guidelines. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;126:303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salti I., Bénard E., Detournay B., Bianchi-Biscay M., Le Brigand C., Voinet C., et al. A population-based study of diabetes and its characteristics during the fasting month of Ramadan in 13 countries: results of the epidemiology of diabetes and Ramadan 1422/2001 (EPIDIAR) study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2306–2311. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munster V.J., Koopmans M., van Doremalen N., van Riel D., de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China – key questions for impact assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B., Zhao J., Liu H., Peng J., et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li B., Yang J., Zhao F., Zhi L., Wang X., Liu L., et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol: Off J German Cardiac Soc. 2020;109:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang J.K., Feng Y., Yuan M.Y., Yuan S.Y., Fu H.J., Wu B.Y., et al. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med: J Br Diabet Assoc. 2006;23:623–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanif S., Ali S.N., Hassanein M., Khunti K., Hanif W. Managing people with diabetes fasting for ramadan during the COVID-19 pandemic: A South Asian health foundation update. Diabet Med: J Br Diabet Assoc. 2020;37:1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/dme.14312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al Awadi F.F., Echtay A., Al Arouj M., Sabir Ali S., Shehadeh N., Al Shaikh A., et al. Patterns of diabetes care among people with type 1 diabetes during Ramadan: An international prospective study (DAR-MENA T1DM) Adv Therapy. 2020;37:1550–1563. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01267-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabeen B., Ahmed B., Nahar J. Young people with type 1 diabetes on insulin pump therapy could fast safely during COVID 19 pandemic Ramadan – a telemonitoring experience in Bangladesh. J Diabet Investig. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jdi.13449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alawadi F., Alsaeed M., Bachet F., Bashier A., Abdulla K., Abuelkheir S., et al. Impact of provision of optimum diabetes care on the safety of fasting in Ramadan in adult and adolescent patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;169:108466. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association A.D. 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S66. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan W., Afandi B. Blood glucose fluctuation during Ramadan fasting in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: findings of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e162–e163. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeb A., Al Qahtani N., Akle M., Singh H., Assadi R., Attia S., et al. Attitude, complications, ability of fasting and glycemic control in fasting Ramadan by children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;126:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan W., Afandi B., Al Hassani N., Hadi S., Zoubeidi T. Comparison of continuous glucose monitoring in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Ramadan versus non-Ramadan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;134:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Hawary A., Salem N., Elsharkawy A., Metwali A., Wafa A., Chalaby N., et al. Safety and metabolic impact of Ramadan fasting in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. 2016;29:533–541. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2015-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadiri A., Al-Nakhi A., El-Ghazali S., Jabbar A., Al Arouj M., Akram J., et al. Treatment of type 1 diabetes with insulin lispro during Ramadan. Diabetes Metabolism. 2001;27:482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bin-Abbas B.S. Insulin pump therapy during Ramadan fasting in type 1 diabetic adolescents. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:305–306. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loh H.H., Lim L.L., Loh H.S., Yee A. Safety of Ramadan fasting in young patients with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:1490–1501. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elbarbary N.S. Effectiveness of the low-glucose suspend feature of insulin pump during fasting during Ramadan in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes/metabolism Res Rev. 2016;32:623–633. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alamoudi R., Alsubaiee M., Alqarni A., Saleh Y., Aljaser S., Salam A., et al. Comparison of insulin pump therapy and multiple daily injections insulin regimen in patients with type 1 diabetes during Ramadan fasting. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19:349–354. doi: 10.1089/dia.2016.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui E., Bravis V., Salih S., Hassanein M., Devendra D. Comparison of Humalog Mix 50 with human insulin Mix 30 in type 2 diabetes patients during Ramadan. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1095–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmedani M.Y., Alvi S.F.D., Fawwad A., Basit A. Implementation of Ramadan-specific diabetes management recommendations: a multi-centered prospective study from Pakistan. J Diabetes Metabolic Disorders. 2014;13:37. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benbarka M.M., Khalil A.B., Beshyah S.A., Marjei S., Awad S.A. Insulin pump therapy in Moslem patients with type 1 diabetes during Ramadan fasting: an observational report. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:287–290. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalil A.B., Beshyah S.A., Abu Awad S.M., Benbarka M.M., Haddad M., Al-Hassan D., et al. Ramadan fasting in diabetes patients on insulin pump therapy augmented by continuous glucose monitoring: an observational real-life study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:813–818. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassem H., Zantout M., Azar S. Insulin therapy during Ramadan fast for Type 1 diabetes patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:802–805. doi: 10.1007/BF03347569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faruqi I., Mazrouei L.A., Buhumaid R. Impact of Ramadan on emergency department patients flow; a cross-sectional study in UAE. Adv J Emergency Med. 2020;4:e22. doi: 10.22114/ajem.v0i0.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elbarsha A., Elhemri M., Lawgaly S.A., Rajab A., Almoghrabi B., Elmehdawia R.R. Outcomes and hospital admission patterns in patients with diabetes during Ramadan versus a non-fasting period. Ann Saudi Med. 2018;38:344–351. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2018.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmedani M.Y., Haque M.S., Basit A., Fawwad A., Alvi S.F. Ramadan Prospective Diabetes Study: the role of drug dosage and timing alteration, active glucose monitoring and patient education. Diabet Med: J Br Diabet Assoc. 2012;29:709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmedani M.Y., Hashmi B.Z., Ulhaque M.S. Ramadan and diabetes - knowledge, attitude and practices of general practitioners; a cross-sectional study. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32:846–850. doi: 10.12669/pjms.324.9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.