Editor—The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has put the safety of healthcare providers at risk,1 especially after aerosol-generating medical procedures such as tracheal intubation and extubation.2 To improve the safety of healthcare providers, many aerosol-generating medical procedures have been modified and adapted in most clinical practices. For instance, recent guidelines for airway management in patients with COVID-193 recommend that all intubations be performed with videolaryngoscopy instead of direct laryngoscopy, not only to improve the success rate of a first-pass tracheal intubation, but also to distance healthcare providers from the airway and infectious aerosols. These recommendations are based on the assumption that increased distance from the patient's airway decreases the potential exposure to infectious droplets. However, the assumption that distance decreases infection risks remains unproved in the setting of aerosol-generating procedures. We therefore examined the relationship between distance and concentration of aerosols during simulated intubation of an airway manikin.

An aerosol nebuliser (Airlife Misty Max 10 Disposable Nebulizer, Carefusion, San Diego, CA, USA) introduced aerosolised saline into the trachea of an airway manikin to simulate passive breathing during intubation.4 The particle concentrations (μg m−3) of particulate matter with diameter <1 mm (PM1), <2.5 mm (PM2.5), and <10 mm (PM10) were measured using a particle counter (Digital PM2.5 Air Quality Detector, Greekcrit, Banggood, Guangzhou, China).4 One particle counter was placed 30 cm above the manikin's head and the other was positioned 60 cm above the manikin's head to approximate the height of the healthcare provider performing an aerosol-generating procedure using direct laryngoscopy or videolaryngoscopy. Measurements were taken every second for 5 min in the following sequence: (a) at time 0 min, the nebuliser was then activated for 3 min to simulate passive breathing during manual ventilation and intubation; (b) at time 3 min, the nebuliser was discontinued to simulate a secured airway; (c) measurements continued for an additional 2 min until particle concentrations reached baseline levels. The measurements were performed five times. The mean particle concentrations and their 95% confidence intervals are plotted (Fig. 1 ). All measurements were performed on a surgical bed at the centre of a standard operating room with laminar flow and an hourly air exchange rate of 27 with the door closed.

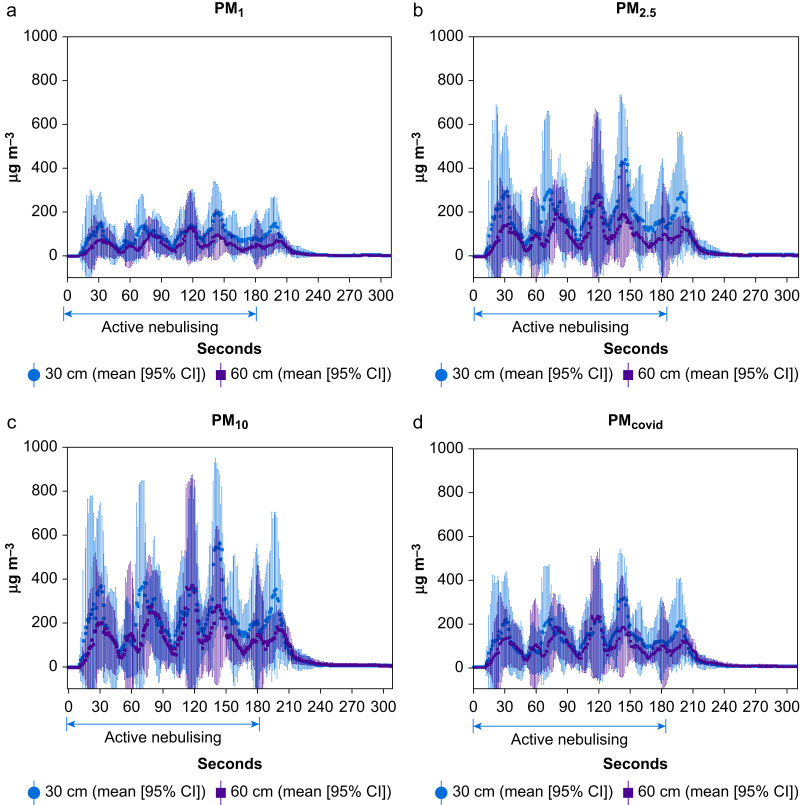

Fig 1.

The mean of five measurements of particle concentrations (μg m−3) measured at 30 cm (red circle: mean [95% CI]) and 60 cm (blue solid square: mean [95% CI]) above the manikin's head for particulate matter diameter sizes: (a) PM1: <1 μm, (b) PM2.5: <2.5 μm, (c) PM10: <10 μm, and (d) PMcovid: sum of particulate matter diameter sizes <1 μm (i.e. PM1) and between 2.5 and 10 μm to simulate severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) aerosols. CI, confidence interval.

This study objectively measured and supports the assumption that increased distances decrease the particle concentrations for all particulate matter diameter sizes (PM1, PM2.5, and PM10). However, this effect was limited to the first 30 s during an aerosol-generating procedure as seen in Figure 1. Beyond 30 s, the increased distance by 30 cm did not offer continued decreases in particle exposure. Particle concentrations became similar with multiple peaks between the two distances above the manikin's head. Although the mechanism of the observed multiple peaks is unclear, this may reflect the time required for redistribution and equilibration of aerosolised particles, especially those with smaller diameters, within the high dynamic airflow of a standard operating room. Because aerosolised SARS-CoV-2 droplets fall within two diameter sizes, between 0.25 μm and 1 μm and >2.5 μm,5 we estimated the particle concentration of ‘PMcovid’ by summing the particle concentrations of PM1 with the difference of PM10 minus PM2.5. PMcovid mirrored the behaviour of the other particulate matter diameter sizes. Thus, although the benefit of decreased particle concentrations as a result of increased distance is brief, it may be sufficient for most rapid intubations as the average intubation time is ∼15 s.5

Our study illustrates the potential benefits of increased distances in reducing aerosolised exposure during aerosol-generating procedures. However, the actual clinical benefit remains unknown. It is important to note that distances of 30 cm and 60 cm above the manikin's head are greater than previously reported mean intubation distances of 15 cm during direct laryngoscopy and 35 cm during videolaryngoscopy,6 although most healthcare providers have increased the distance at which they perform aerosol-generating procedures during this pandemic. Thus, we decided to study distances of 30 cm and 60 cm as reflective of recent changes in clinical practice.

With experts bracing for a second wave of COVID-19 and the continued high incidence of infection from the first wave,7 further studies are needed to refine our understanding of the behaviour of aerosolised particles and to better elucidate the assumptions we rely on to keep healthcare providers safe when performing aerosol-generating procedures. In addition to distance, exposure to aerosolised particles is dependent on the duration of suspension, which is not only affected by particle size and concentration, but also by the surrounding air flow where the aerosol-generating procedure is performed. To prepare for a second wave and optimise safety, clinicians should assess the behaviour of aerosols and airflow dynamics within their individual clinical practices and operating rooms.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhan M., Qin Y., Xue X., Zhu S. Death from Covid-19 of 23 health care workers in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2267–2268. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinzerling A., Stuckey M.J., Scheuer T. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient - Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:472–476. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao W., Wang T., Jiang B. Emergency tracheal intubation in 202 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: lessons learnt and international expert recommendations. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsui B.C.-H., Deng A., Lin C., Okonski F., Pan S. Droplet evacuating strategy for simulated coughing during aerosol generating procedures in COVID-19 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e299–e301. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Ning Z., Chen Y. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582:557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall D., Steel A., Heij R., Eley A., Young P. Videolaryngoscopy increases ‘mouth-to-mouth’ distance compared with direct laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:822–823. doi: 10.1111/anae.15047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu S., Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1321–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]