Abstract

Introduction

Since the beginning of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States, there have been concerns about the potential impact of the pandemic on persons with opioid use disorder. Shelter-in-place (SIP) orders, which aimed to reduce the spread and scope of the virus, likely also impacted this patient population. This study aims to assess the role of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of opioid overdose before and after a SIP order.

Methods

A retrospective review of the incidence of opioid overdoses in an urban three-hospital system was conducted. Comparisons were made between the first 100 days of a city-wide SIP order during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 100 days during the COVID-19 pandemic preceding the SIP order (Pre-SIP). Differences in observed incidence and expected incidence during the SIP period were evaluated using a Fisher's Exact test.

Results

Total patient visits decreased 22% from 46,078 during the Pre-SIP period to 35,971 during the SIP period. A total of 1551 opioid overdoses were evaluated during the SIP period, compared to 1665 opioid overdoses during the Pre-SIP period, consistent with a 6.8% decline. A Fisher's Exact Test demonstrated a p < 0.0001, with a corresponding Odds Ratio of 1.20 with a 95% confidence interval (1.12;1.29).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated SIP order were associated with a statistically and clinically significant increase in the proportion of opioid overdoses in relation to the overall change in total ED visits.

Keywords: Opiate overdose, Opioid epidemic, COVID-19, Pandemics, Shelter in place

1. Introduction

Prior to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, healthcare practitioners in the US were battling with a different epidemic- the opioid crisis. Similar to COVID-19, the weight of opioid overdose care is managed by emergency departments (EDs) across the country. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, ED patient volumes were steadily increasing [1,2]. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, normally overcrowded EDs have been less congested. Media outlets and studies have reported that in many EDs, visits have nearly dropped in half [[3], [4], [5]]. This striking disappearance of everyday emergencies has been noted both nationally and internationally, but less is known about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid overdose rates [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]].

Data published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed that in 2017 the opioid crisis took the lives of 130 Americans per day. Drug overdoses have dramatically increased over the past two decades [12,13]. As increasing numbers of patients are being treated for opioid overdose, many organizations have expressed concern that the COVID-19 pandemic may disproportionately affect persons with substance use disorders (SUDs) [14,15]. Social support is crucial for those being treated for SUDs, and stress and isolation put persons at risk for relapse [16]. Persons with SUD face unique challenges during times of quarantine and stay at home orders. Many individuals with SUDs have underlying health conditions, particularly cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases and Hepatitis C or Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 infection [16]. Coupled with a lack of resources for social distancing and hygiene, these populations are more vulnerable to COVID-19 transmission [17]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that economic conditions may be a strong predictor of drug-related deaths [18]. Additionally, people with SUDs are also at a particularly heightened risk of suicide [19]. While efforts to physically distance are vital to slow the spread of the virus, this may have unintended consequences on mental health and persons with SUDs are likely to suffer more greatly from the psychosocial burden [20].

Furthermore, persons seeking treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) may require frequent medical appointments, individual or group therapy, or daily visits to methadone clinics. Disruption of care is a large threat to addiction treatment, and the COVID-19 pandemic entered the US just as more and more people were gaining access to SUD treatment and medication assisted therapy [21]. This prompted some practitioners in the US to advocate for expanded mobile and telemedicine solutions for SUDs during the pandemic [22]. In fact, the Drug Enforcement Administration demonstrated quick legislative change and permitted prescription of buprenorphine through telemedicine [23]. During the pandemic in China, authorities required public security departments to ensure that methadone was delivered from clinics to their patients' homes [24].

At the beginning of the pandemic, many large cities enacted “shelter-in-place” (SIP) orders, in an attempt to limit the spread of COVID-19 [25]. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania enacted a similar order, which went into effect on March 23rd, 2020 and ended June 4th, 2020. Under the order's provisions all public and private gatherings of any number of people occurring outside a single household were prohibited with exceptions made for essential businesses or essential personal activities [26]. These measures are important for limiting spread of disease in a pandemic, but may further personal isolation.

Reports from national, state and local media outlets have suggested increases in opioid-related mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. Despite these concerns, there has been little published data regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on reported opioid overdoses. This study aimed to assess the role of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated SIP order on the incidence of opioid overdoses.

2. Methods

This was a retrospective, observational study of patients seen in our health system in Philadelphia, PA. Total annual volume in the health system in 2019 was approximately 180,000 visits. Charts of those patients evaluated for opioid overdose were identified using the EPIC electronic health record system (Verona, WI) via ICD10 codes T40.0–40.4, T40.6, F11.0-F11.9. These codes include diagnoses such as poisoning by heroin, poisoning by other opioids, and poisoning by narcotics, which represent various classifications of opioid overdose.

The study period included 100 days after a shelter-in-place (SIP) order in Philadelphia, from March 23, 2020 - June 30, 2020. This was compared to the 100 days prior to the SIP order (Pre-SIP), from December 14, 2019 - March 22, 2020. To account for changes in overall ED volume, a Central Fisher's Exact Test was used to compare the ratio of observed to expected patients evaluated during both time periods. This study was not considered human subject research by our Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

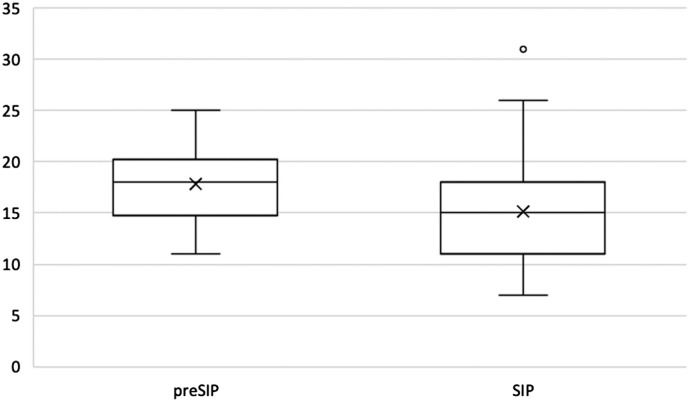

Summary data is shown in Table 1 . Overall patient visits decreased 22%, from 46,078 during the Pre-SIP period to 35,971 during the SIP period. There was a 6.8% decline in overdoses, from 1665 during the Pre-SIP period, to 1551 during the SIP period. The difference between expected and observed opioid overdoses in the study EDs was significant (p < 0.0001), with a corresponding Odds Ratio of 1.202 and a 95% Confidence interval of 1.12 to 1.29 (Fig. 1 ).

Table 1.

Incidence of opioid overdoses.

| Total evaluations | Total OUD evaluations | Daily incidence | Fisher's exact test | Odds ratio | Odds ratio 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-SIP | 46,078 | 1665 | 16.65 ± 4.23 | p < 0.0001 | 1.20 | (1.12–1.29) |

| SIP | 35,971 | 1551 | 15.51 ± 4.51 |

SIP = Shelter In Place (3/23/20–06/30/20); Pre-SIP = pre-Shelter in Place (12/14/19–03/22/2020); Incidence reported as daily mean +/− 2 standard deviations.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of daily opioid overdoses. This figure illustrates the distribution of daily number of overdose patients evaluated per study period.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and a concomitant SIP order on the incidence of opioid overdoses. We found a 22% decrease in the total number of patients seen in the ED during the SIP period. There was a significantly smaller decrease of 6.8% in opioid overdoses during the same time period. Therefore, although the absolute number of opioid overdoses declined during the SIP period, there were proportionally more opioid overdoses during that period, compared to overall ED volume. This suggests that opioid overdoses continued at a large rate despite the SIP order.

In the city of Philadelphia, opioid overdoses have been increasing steadily since at least 2013 [31]. Based on prior trajectories, the rate of overdose was expected to continue to increase in 2020. Overall overdose deaths in Philadelphia are about the same this year as they were last year, though notability both fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses increased in black residents [32].

It seems likely that the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the rate of increase in opioid overdose presentations to EDs, rather than caused a true decrease in overdoses. By comparison, one ED in Virginia noted that their total number of nonfatal opioid overdose visits doubled in the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the year prior [33]. Similarly, data from the Kentucky State Ambulance Reporting System demonstrated a 17% increase in EMS opioid overdose runs and a 50% increase in runs for suspected opioid overdose with deaths at the scene after a state of emergency was declared [34]. This study also demonstrated a 71% increase in EMS runs with refused transportation to an ED suggesting that patients are less likely to present to a hospital. Multiple previous studies have noted a decrease in presentation of everyday emergencies, speculating that patients, including those with opioid use disorder, may be fearful to present to an ED during a pandemic [[8], [9], [10], [11]].

The cause of the decrease in opioid overdose presentation is likely multifactorial. One possible explanation is that people that travel to the area near the study site to obtain opioids did not do so out of fear of exposure, and instead obtained opioids in their local areas. Bystanders may have been less likely to contact 9–1-1 in an effort to avoid EDs during the pandemic. It is also possible that the broad availability and use of Naloxone, by both first responders and bystanders, may have limited the number of opioid overdose presentations. Furthermore, the US enacted travel bans from China on February 2nd, 2020, and parts of Europe on March 11th, 2020. It is likely that travel restrictions and social distancing also impacted imports from Mexico to the US. Wuhan, China was well-known as a hub for Fentanyl, whereas Mexico is known for Fentanyl, Heroin, Cocaine, and Methamphetamines [35,36]. The US DEA has reported disruptions in supply-chains of illegal drugs all over the US, including in Philadelphia [36]. With reduction in supply comes increased demand, which is almost always followed by increased prices. The combination of a reduced supply and higher cost may have impacted those with OUD and limited their ability to purchase and use opioids.

The significant impact of the SIP order is curious, because many patients seen in the study ED for overdose are un-domiciled, and therefore, have nowhere to shelter. During the SIP order, private transportation modalities, such as Uber and Lyft, were not as available, and public transportation schedules were altered to reduce trips and hours. The impact of the SIP on transportation modalities could have further impacted the population that travels to the study area to obtain opioids, rather than the population that resides in the study area.

5. Limitations

This study was conducted within a single health system in an urban setting that cares for a high number of patients presenting with opioid use disorder, and so, results may not be generalizable to all hospital settings or patient populations. While this study examined the 100 days after the SIP order (March 23rd through June 30th, 2020), this order expired on June 4th, 2020. We believe that the SIP order influenced culture which continued after the order; however, it is possible that people's behavior changed immediately upon expiration of the order. Additionally, the ICD-10 codes used to capture visits related to opioid overdose were based on those used in existing literature, but may not have been inclusive of all visits related to opioid overdose. We were also unable to capture data from opioid overdoses in the prehospital setting that did not present to the ED. Furthermore, our study did not measure mortality from overdoses during this timeframe.

6. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated SIP order were associated with an overall decrease in opioid overdoses. Compared to overall ED volume, however, the proportional increase in opioid overdoses was statistically and clinically significant.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Lin M.P., Baker O., Richardson L.D., Schuur J.D. Trends in emergency department visits and admission rates among US acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1708–1710. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf (Published 2017. Accessed May 14, 2020)

- 3.Pan D. ‘Strokes and Heart Attacks don't Take a Vacation.’ So Why have Emergency Department Visits Sharply Declined? Boston Globe. 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/23/nation/strokes-heart-attacks-dont-take-vacation-so-why-have-emergency-department-visits-sharply-declined/

- 4.Feuer W. Doctors Worry the Coronavirus is Keeping Patients Away from US Hospitals as ER Visits Drop: 'Heart attacks don't stop'. CNBC. 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/14/doctors-worry-the-coronavirus-is-keeping-patients-away-from-us-hospitals-as-er-visits-drop-heart-attacks-dont-stop.html Published April 14, 2020. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 5.Butt A.A., Azad A.M., Kartha A.B., Masoodi N.A., Bertollini R., Abou-Samra A.-B. Volume and acuity of emergency department visits prior to and after COVID-19. J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin C. As COVID-19 Spreads, Massachusetts Hospitals see Decline in Visits for Other Illnesses. Boston.com. 2020. https://www.boston.com/news/health/2020/03/30/massachusetts-coronavirus-emergency-rooms Published March 31, 2020. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 7.Thornton J. Covid-19: A&E visits in England fall by 25% in week after lockdown. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feral-Pierssens A.-L., Claret P.-G., Chouihed T. Collateral damage of the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Emerg Med. May 2020 doi: 10.1097/mej.0000000000000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kansagra A.P., Goyal M.S., Hamilton S., Albers G.W. Collateral effect of Covid-19 on stroke evaluation in the United States. N Engl J Med. May 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmc2014816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zitelny E., Newman N., Zhao D. STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic - an evaluation of incidence. Cardiovasc Pathol. May 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrester J.D., Liou R., Knowlton L.M., Jou R.M., Spain D.A. Impact of shelter-in-place order for COVID-19 on trauma activations: Santa Clara County, California, March 2020. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2020;5(1) doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.America's Drug Overdose Epidemic - Data to Action. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/prescription-drug-overdose/index.html Published March 24, 2020. Accessed May 22, 2020.

- 13.CDC's Response to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/strategy.html Published January 11, 2019. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 14.Understanding the Epidemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html Published March 19, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 15.Moroni F., Gramegna M., Ajello S., et al. Collateral damage: medical care avoidance behavior among patients with acute coronary syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC: Case Reports. April 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volkow N.D. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 2;2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1212. (published online ahead of print) M20-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parshley L. The Pandemic may Fuel the Next Wave of the Opioid Crisis. National Geographic. April 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/04/coronavirus-pandemic-may-fuel-the-next-wave-of-the-opioid-crisis/ Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 18.Strumpf E.C., Charters T.J., Harper S., Nandi A. Social Science & Medicine. 2017. Did the Great Recession affect mortality rates in the metropolitan United States? Effects on mortality by age, gender and cause of death.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953617304495 Published July 21, 2017. Accessed November 10, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch F.L., Peterson E.L., Lu C.Y., et al. Substance Use Disorders and Risk of Suicide in a General US Population: a Case Control Study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32085800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jayasinha R., Nairn S., Conrad P. A dangerous “cocktail”: the COVID-19 pandemic and the youth opioid crisis in North America: a response to Vigo et al. (2020) Can J Psychiatr. 2020;65(10):692–694. doi: 10.1177/0706743720943820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander G.C., Stoller K.B., Haffajee R.L., Saloner B. An epidemic in the midst of a pandemic: opioid use disorder and COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1141. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 2] M20-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker W.C., Fiellin D.A. When epidemics collide: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the opioid crisis. Ann Intern Med. February 2020 doi: 10.7326/m20-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drug Enforcement Administration COVID-19 Information Page. COVID-19 Information Page. 2020. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/coronavirus.html Accessed May 14, 2020.

- 24.Sun Y., Bao Y., Kosten T., Strang J., Shi J., Lu L. Editorial: challenges to opioid use disorders during COVID-19. Am J Addict. 2020;29(3):174–175. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mervosh S., Lu D., Swales V. See Which States and Cities Have Told Residents to Stay at Home. The New York Times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html

- 26.Office of the Mayor. City Issues Stay at Home Order Clarifying Restrictions on Business Activity in Philadelphia: Department of Commerce. 2020. https://www.phila.gov/2020-03-22-city-issues-stay-at-home-order-clarifying-restrictions-on-business-activity-in-philadelphia/ City of Philadelphia. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 27.Kamp J., Campo-Flores A. The Opioid Crisis, Already Serious, Has Intensified During Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-opioid-crisis-already-serious-has-intensified-during-coronavirus-pandemic-11599557401 The Wall Street Journal.

- 28.Mann B. U.S. Sees Deadly Drug Overdose Spike During Pandemic. NPR. 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/08/13/901627189/u-s-sees-deadly-drug-overdose-spike-during-pandemic Published August 13, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 29.Kagan H. Opioid Overdoses on the Rise During COVID-19 Pandemic, Despite Telemedicine Care. ABC News. 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/opioid-overdoses-rise-covid-19-pandemic-telemedicine-care/story?id=72442735 Published August 24, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 30.Kurutz D.R. 2020. https://www.timesonline.com/story/news/2020/09/05/covid-sends-opioid-crisis-into-tailspin/5715587002/ COVID sends opioid crisis into tailspin. The Times.

- 31.Board of Health, Department of Public Health, Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disability Services Opioid Misuse and Overdose Data|Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disability Services. City of Philadelphia. 2020. https://www.phila.gov/programs/combating-the-opioid-epidemic/reports-and-data/opioid-misuse-and-overdose-data/ Published February 12, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- 32.Whelan A. Philadelphia's Drug Pandemic, Like COVID-19, Now Puts the Heaviest Burden on Black Residents, Data Show. 2020. https://www.inquirer.comhttps://www.inquirer.com/health/opioid-addiction/overdose-deaths-philadelphia-black-residents-20200826.html Published August 26, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 33.Ochalek T.A., Cumpston K.L., Wills B.K., Gal T.S., Moeller F.G. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jama. 2020;324(16):1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slavova S., Rock P., Bush H.M., Quesinberry D., Walsh S.L. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108176. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linthicum K. Wuhan was a Fentanyl Capital. Then Coronavirus Hit - Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. 2020. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-04-24/wuhan-china-coronavirus-fentanyl-global-drug-trade Published April 24, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- 36.Jones D. Coronavirus Disrupts Illegal Drug Supply in U.S., DEA Official Says - ProQuest. Dow Jones Institutional News. 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-disrupts-illegal-drug-supply-in-u-s-dea-official-says-11587043059 Published April 16, 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020.