Abstract

This paper is intended to explore a higher order stochastically perturbed SIRI epidemic model with relapse and media coverage. Firstly, we derive sufficient criteria for the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution of positive solutions to the system by establishing a suitable stochastic Lyapunov function. Then we obtain adequate conditions for complete eradication and wiping out of the infectious disease. In a biological interpretation, the existence of a stationary distribution implies that the disease will prevail and persist in the long term. Finally, the theoretical results are illustrated by computer simulations, including two examples based on real-life disease.

Keywords: SIRI epidemic model, Relapse, Media coverage, Stationary distribution, Ergodicity, Extinction

1. Introduction

In modern society, there is no doubt that public health issue has become a great threat to the global personal and property security, we must take some self-protection measures during the epidemic period. The probe of mathematical modeling is a good way to describe the transmission dynamics of infectious disease and provide effective control strategies [1]. Recently, many scholars have constructed an idea of mathematical models to investigate the dynamics of infectious disease which is named as compartmental model. In the epidemic models the total population is classified as the susceptible compartment (S), the infected compartment (I) and the recovered compartment (R). There exist few occurrences where susceptibles become infectious, then are recovered with temporary immunity and then become infectious again which is called as SIRI model. This recurrence of disease is an important characteristic of some animal and human diseases, for example, tuberculosis including human and bovine and herpes [2], [3].

In case of the breakout of infectious disease in a particular region, the immediate endeavour of disease control authorities is to make a ultimate venture to contain the spread of disease. Educating people about the disease via numerous agencies such as mass media, etc, is one of the significant preventive measures. Mass media plays an important role in propagating the nature and the cause of assorted deadly diseases such as respiratory disease, hepatitis diseases, human immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV), Avian influenza A (H7N9), human tuberculosis (TB), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Ebola virus disease (EVD), etc. Recently, numerous mathematical models have been developed to study the influence of media coverage on the dynamics of infection disease [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Caraballo et al. [10], Sun et al. [11] and Li and Cui [12] employed deterministic models to study the impacts of media coverage on the transmission dynamics, in view of the following incidence

where β 1 indicates the contact rate after and before media alert respectively; the term represents the diminished value of the transmission rate when infectious individuals are taken into account. If the infectives are adequately large then the diminished value of the transmission rate tends to its maximum β 2, and infectives reaches m, the diminished value of the transmission rate equals half of the maximum β 2. Due to the inability of the coverage report to prevent disease, spreading rampantly, we have β 1 ≥ β 2 > 0, m denotes reactive velocity of the people and media coverage to the disease. The term is a continuous bounded function that describes psychological influences or disease saturation. Then the deterministic SIR epidemic model with relapse and media coverage can be expressed as follows:

| (1.1) |

where Λ, μ 1, μ 2, μ 3, β 1, β 2, m, γ, δ are all positive constants, S denotes the numbers of the individuals susceptible to the disease, I denotes the infected members and R is the members who have recovered from the infection. The parameters have the following biological meanings: Λ represents the recruitment rate, μ 1, μ 2, μ 3 are the natural death rate of susceptible, infected and recovered compartments respectively. The parameter γ reflects recover rate with temporary immunity and δ represents the relapse rate. The basic reproduction number [13], [14]

has a great importance in epidemiology since it is a threshold quantity which determines whether an epidemic occurs or the disease dies out. The following behaviors of solutions according to the value of the threshold can be given:

• If then system (1.1) has only the disease-free equilibrium

and it is globally asymptotically stable in the invariant set Θ.

• If then E 0 is unstable, and there is a unique endemic equilibrium with S* > 0, I* > 0 and R* > 0 which is globally asymptotically stable in the interior of Θ, where

However, it is well established that epidemic systems are always subjected to environmental white noise and the influence of fluctuating environmental white noise is not inclusive in the deterministic models [15]. Thus, the deterministic epidemic model has some restrictions to predict the future dynamics accurately [16]. Recently, stochastic differential equation models [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22] have played an important role in various branches of applied sciences including infection dynamics and population dynamics, since they can provide some additional degree of realism compared to their deterministic counterparts [23]. And it is hence interesting to introduce the stochastic perturbation into the deterministic system to reveal the effect of environmental white noise on human disease [18], [21], [24], [25], [26], [27]. For example, Gray et al. [18] investigated a stochastic SIS epidemic model with constant population size and degenerate diffusion. They established conditions for extinction and persistence of the disease. Moreover, in the case of persistence, they showed the existence of a stationary distribution and obtained expressions for its mean and variance. In [21], Liu et al. studied the dynamical behavior of a stochastic SIRI epidemic model with relapse and constant population size. The authors used the Markov semigroup theory to obtain the existence of a stable stationary distribution. Caraballo [27] analyzed a stochastic epidemic model with isolation and nonlinear incidence. They established sufficient condition for extinction and obtained necessary and sufficient conditions for persistence in mean of the disease. In particular, they derived the stochastic threshold for the model. However, in the literatures [18], [21] and [27], the authors didn’t consider the effect of the media coverage. In addition, in the literatures [18] and [21], the diffusion matrix is degenerate, the authors cannot use the Has’minskii’s theory to obtain the ergodicity of a stationary distribution, while in the literature [27], although the diffusion matrix is nondegenerate, the authors didn’t studied the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution which implies stochastic weak stability. Accordingly, it is necessary for us to consider both of them together.

To incorporate the effect of environmental white noise, in this paper, motivated by the approach proposed by Liu and Jiang [28], we construct a stochastic differential equation model by introducing the nonlinear perturbation into each equation of system (1.1) as the stochastic perturbation may be dependent on square of the variables S, I and R, respectively. Then to make model (1.1) more reasonable and realistic, we introduce a corresponding stochastic model as follows:

| (1.2) |

subject to the initial conditions

Here Bi(t) denote mutually independent standard Brownian motions defined on a complete probability space with a filtration satisfying the usual conditions [29], σ 11 > 0, σ 12 > 0, σ 21 > 0, σ 22 > 0, σ 31 > 0 and σ 32 > 0 denote the intensities of the environmental random disturbance. Note that this model appears when we assume that the parameters μ 1, μ 2 and μ 3 are disturbed by some stochastic perturbation in each equation, that is to say, we replace μ 1, μ 2 and μ 3 by

in each equation, respectively. A large number of scholars concentrate only on media coverage and they have not considered media coverage with relapse and higher order perturbation [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [30]. Yet another group of scholars focus only on higher order perturbation [19], [28], [31], [32], [33]. Therefore, it is necessitated that we focus on them together. Investigating such problem is important and meaningful.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we establish sufficient criteria for the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution of positive solutions to the stochastic system (1.2). In Section 3, we obtain sufficient criteria for extinction of the disease. In Section 4, the presented results are demonstrated and confirmed by numerical simulations. Finally, conclusion is provided to end this paper.

Throughout this paper, if G is a matrix, its transpose is denoted by GT. Moreover, we introduce the following notations:

To proceed, we should first give some condition under which system (1.2) has a unique global positive solution. Since the proof is similar to the statement of Lemma 1.1 in Liu and Jiang [28], we only state the result without proof.

Lemma 1.1

For any initial value S0 > 0, I 0 ≥ 0, R 0 ≥ 0, there is a unique solution (S(t), I(t), R(t)) to system (1.2) on t ≥ 0 and the solution will remain in with probability one, namely, for all t ≥ 0 almost surely (a.s.).

2. Existence of ergodic stationary distribution

In this section, we will establish sufficient criteria for the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution of positive solutions to the stochastic system (1.2). In a biological viewpoint, the existence of a stationary distribution implies that the disease will be prevalent and persistent when the intensities of stochastic perturbations are adequately small.

Let X(t) be a regular time-homogeneous Markov process in described by the stochastic differential equation

The diffusion matrix of the process X(t) is defined as follows

Lemma 2.1

[34]. The Markov process X(t) has a unique ergodic stationary distribution π( · ) if there exists a bounded open domain with regular boundary Γ, having the following properties:

A1: the diffusion matrix A(x) is strictly positive definite for all x ∈ U.

A2: there exists a nonnegative C2-function V such that LV is negative for any.

Lemma 2.2

For any x ≥ 0, the following two inequalities hold

The proofs are based on the following facts

Theorem 2.1

Assume thatthen system(1.2)admits a unique stationary distribution π( · ) and it has the ergodic property.

Proof

To prove Theorem 2.1, we only need to verify conditions A 1 and A 2 in Lemma 2.1. We first verify the condition A 1. The diffusion matrix of system (1.2) is given by

Obviously, the matrix A is positive definite for any compact subset of so the condition A 1 in Lemma 2.1 holds.

Now we verify the condition A 2. For any adequately small constant p ∈ (0, 1), define

Evidently, . Due to the continuity of the function and we can pick p adequately small such that . In view of system (1.2), we obtain

(2.1)

(2.2) and

(2.3) Define

where a 1, a 2, b 1, b 2, c 1, c 2, c 3, d 1, d 2 and d 3 are positive constants which will be determined later. Applying Itô’s formula to V 1, we get

where in the third inequality, we have used Lemma 2.2. Choose

then we have

(2.4) Thus, from (2.1) and (2.4) it follows that

(2.5) Next, applying Itô’s formula to V 2, we have

where in the third inequality, we have used Lemma 2.2. Choose

then we obtain

(2.6) Therefore, by (2.2) and (2.6), we have

(2.7) Moreover, according to (2.3), we derive

Choose

then

(2.8) Analogously, we have

(2.9) Consequently, in view of (2.5), (2.7) and (2.8), we obtain

Choose

then we obtain

(2.10) where

Define a C 2-function in the following form

where M > 0 is a sufficiently large number satisfying the following condition

(2.11) and

In addition, notice that is not only continuous, but also tends to ∞ as (S, I, R) approaches the boundary of . So it should be lower bounded and achieve this lower bound at a point (S 0, I 0, R 0) in the interior of . Then we define a C 2-function as follows

From (2.1), (2.3), (2.9) and (2.10) it follows that

(2.12) Now we are in the position to construct a bounded open domain U ϵ such that the condition A 2 in Lemma 2.1 holds. Define a bounded open set as follows

where 0 < ϵ < 1 is a small enough number. In the set we can select ϵ small enough such that the following conditions hold

(2.13)

(2.14)

(2.15)

(2.16)

(2.17)

(2.18)

(2.19) where J 2 is a positive constant which will be given explicitly in expression (2.21). For the sake of convenience, we can divide into six domains,

Evidently, . Next, we will show that for any which is equivalent to verifying it on the above six domains, respectively.

Case 1. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 1, in view of (2.12), we obtain

(2.20) which follows from (2.13) and

(2.21) Case 2. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 2, from (2.12) it follows that

(2.22) which follows from (2.14).

Case 3. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 3, by (2.12), we have

(2.23) which follows from (2.11), (2.15) and (2.16) and

Case 4. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 4, according to (2.12), we get

(2.24) which follows from (2.17).

Case 5. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 5, by (2.12), we derive

(2.25) which follows from (2.18).

Case 6. For any (S, I, R) ∈ U 6, from (2.12) it follows that

(2.26) which follows from (2.19).

Accordingly, from (2.20), (2.22), (2.23), (2.24), (2.25) and (2.26) it follows that for a small enough ϵ,

Hence the condition A 2 in Lemma 2.1 also holds. By Lemma 2.1, we derive that system (1.2) admits a unique stationary distribution π( · ) and it has the ergodic property. This completes the proof. □

Remark 2.1

From the expression of we can obtain that if there is no stochastic perturbation in system (1.2), then so is a generalized result determining the persistence of the disease. In addition, if we only consider the linear perturbation, i.e., then

Therefore, can be regarded as a generalized result of Caraballo et al. [10].

3. Extinction

In this section, we will obtain sufficient criteria for extinction of the disease. To this end, we establish the following theorem.

Theorem 3.1

Let (S(t), I(t), R(t)) be the solution to system (1.2) with any initial value S 0 > 0, I 0 ≥ 0, R 0 ≥ 0, then for almost ω ∈ Ω, the solution has the following property:

(3.1) where

In particular, if ν < 0, then the disease I will die out exponentially with probability one, i.e.,

In addition, the distribution of S(t) converges weakly to the measure which has the density

where Q is a constant such that .

Proof

Consider the following auxiliary logistic equation with stochastic perturbation

(3.2) with initial value .

From Theorem 3.1 of Liu and Jiang [28], we can obtain that system (3.2) has the ergodic property and the invariant density is given by

where Q is a constant such that

Let X(t) be the solution to (3.2) with initial value then employing the comparison theorem of 1-dimensional stochastic differential equation [35], we obtain S(t) ≤ X(t) for any t ≥ 0 a.s.

On the other hand, by Theorem 1.4 of [36], p.27, we can derive that there exists a left eigenvector of

corresponding to (the spectral radius of M 0), which is denoted as i.e.,

Define a C 2-function by

where . Applying Itô’s formula [29] to we obtain

(3.3) where

In addition, by Cauchy inequality, we have

(3.4) Therefore

(3.5) In view of (3.3), (3.4) and (3.5), we obtain

(3.6) Integrating (3.6) from 0 to t and then dividing by t on both sides, we get

(3.7) where

are local martingales whose quadratic variations are respectively

From the strong large numbers theorem it follows that

(3.8) Furthermore, in view of the exponential martingales inequality [29], for any positive constants T, α and β, we have

Choose we obtain

By the Borel-Cantelli Lemma [29], we obtain that for almost all ω ∈ Ω, there is a random integer such that for k ≥ k 0, we derive

That is

(3.9) and

(3.10) for all 0 ≤ t ≤ k, k ≥ k 0 a.s. Substituting (3.9) and (3.10) into (3.7) leads to

for all 0 ≤ t ≤ k, k ≥ k 0 a.s. In other words, we have shown that for

(3.11) Since X(t) is ergodic and a.s., we have

(3.12) Taking the superior limit on both sides of (3.11) and combining with (3.8) and (3.12), we obtain

which is the required assertion (3.1). In addition, if ν < 0, we can easily obtain that

which implies that and a.s. In other words, the disease I will die out exponentially with probability one.

Therefore, for any small ϵ > 0 there are t 0 and a set Ωϵ ⊂ Ω such that and for t ≥ t 0 and ω ∈ Ωϵ. Now from

it follows that the distribution of the process S(t) converges weakly to the measure with the density π. This completes the proof. □

Remark 3.1

From Theorem 3.1, we can derive that if and are sufficiently large such that ν < 0, then the disease will die out exponentially a.s. However, as far as we know, in the deterministic system (1.1), if then the endemic equilibrium E* is globally asymptotically stable. This shows that the disease will prevail and persist in the long term. Hence our result is very different from the one of the deterministic system (1.1). This shows that large white noise will lead to the eradication of the infectious disease.

4. Numerical simulations

In this section, we will present a realistic example to illustrate our theoretical results, that is Herpes simplex virus type 2. As far as we know, Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is a human disease transmitted by close sexual or physical contact. The virus usually infects the oral mucosa or genital tract. An individual with herpes remains infected for life and the virus reactivate regularly producing a relapse period of infectiousness [10]. For herpes an SIRI model is appropriate. In the following examples we will present some numerical simulations to demonstrate the case of HSV-2. We use the same parameters given by Blower [2]. The detailed values of the parameters are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of parameters.

| Parameters | Description | Values | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Λ | Recruitment rate | 0.1 | [2], [10] |

| β1 | Contact rate before media alert | 0.2 | [2], [10] |

| β2 | Reduction of the contact rate | 0.15 | [2], [10] |

| m | Half-saturation constant | 1 | [2], [10] |

| μ1 | Natural death rate of susceptible compartments | 0.05 | [2], [10] |

| μ2 | Natural death rate of infected compartments | 0.05 | [2], [10] |

| μ3 | Natural death rate of recovered compartments | 0.05 | [2], [10] |

| γ | Recover rate with temporary immunity | 0.2857 | [2], [10] |

| δ | Relapse rate | 0.2857 | [2], [10] |

For the numerical simulations, we use Milstein’s Higher Order Method mentioned in [37] to obtain the corresponding discretization transformation of system (1.2)

where the time increment Δt > 0, ξk, ηk, ζk are mutually independent Gaussian random variables which follow the distribution N(0, 1) for .

Example 4.1. In this example, we choose initial values ; ; and time step . Direct calculation leads to that

That is to say, the condition of Theorem 2.1 holds. In view of Theorem 2.1, we derive that system (1.2) admits a unique ergodic stationary distribution π( · ). See Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The left column shows the paths of S(t), I(t) and R(t) of system (1.2) with initial values ; ; under the noise intensities and . Other parameter values are given in Table 1. The blue lines represent the solution to system (1.2) and the red lines represent the solution to the corresponding undisturbed system (1.1). The right column displays the histogram of the probability density functions of S, I, R populations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

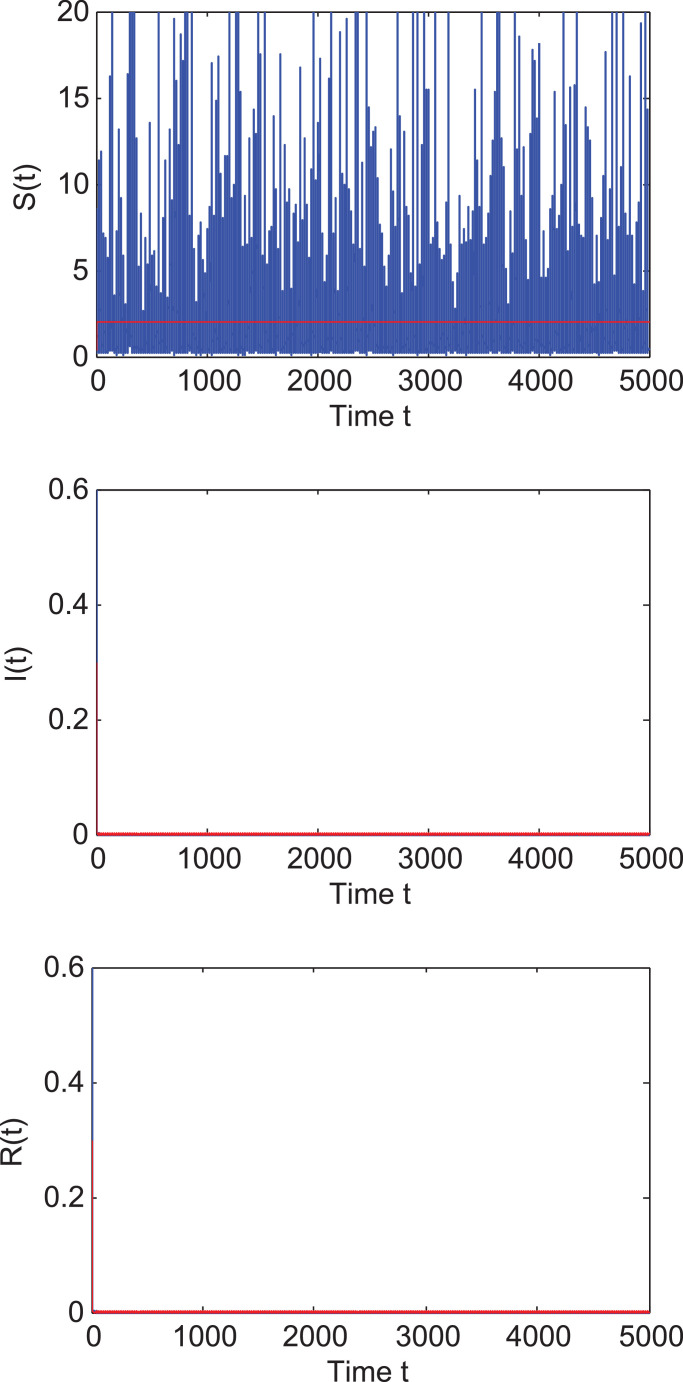

Example 4.2. In this example, we choose initial values ; ; and time step . By a simple computation, we obtain

and

Thus, the condition of Theorem 3.1 is satisfied. That is to say, the disease will be extinct a.s. Fig. 2 illustrates this.

Fig. 2.

The column shows the paths of S(t), I(t) and R(t) of system (1.2) with initial values ; ; under the noise intensities and . Other parameter values are given in Table 1. The blue lines represent the solution to system (1.2) and the red lines represent the solution to the corresponding undisturbed system (1.1). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have studied the salient features of a higher order stochastically perturbed SIRI epidemic model with relapse and media coverage. We first establish sufficient criteria for the existence and uniqueness of an ergodic stationary distribution of positive solutions to the stochastic system (1.2) by constructing a suitable stochastic Lyapunov function. Then we make up adequate conditions for complete eradication and wiping out of the infectious disease. In a biological viewpoint, the existence of a stationary distribution implies that the disease will be prevalent and persistent in the long term. Moreover, it is a meaningful topic to study whether or not the method used in this paper can be also applicable to other stochastic multi-dimensional epidemic models, such as rabies transmission model, malaria transmission model and syphilis transmission model. These works could be hopping taken up by the future studies and aptly solved.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.11871473) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.ZR2019MA010).

References

- 1.Rajasekar S.P., Pitchaimani M., Zhu Q. Progressive dynamics of a stochastic epidemic model with logistic growth and saturated treatment. Physica A. 2020;538:122649. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blower S. Modelling the genital herpes epidemic. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 3):138A–146A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wildy P., Field H.J., Nash A.A. In: Virus persistence symposium. Mahy B.W.J., Minson A.C., Darby G.K., editors. vol. 33. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1982. Classical herpes latency revisited; pp. 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu W. A SIRS epidemic model incorporating media coverage with random perturbation. Abst Appl Anal. 2013;2013:792308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Liu Z., Zhang X. Global dynamics for an age-structured epidemic model with media impact and incomplete vaccination. Nonlinear Anal: Real World Appl. 2016;32:136–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Fan K., Gao S., Liu Y., Chen S. Ergodic stationary distribution of a stochastic SIRS epidemic model incorporating media coverage and saturated incidence rate. Physica A. 2019;514:671–685. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo W., Zhang Q., Li X., Wang W. Dynamic behavior of a stochastic SIRS epidemic model with media coverage. Math Meth Appl Sci. 2018;41:5506–5525. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W., Zheng Q. A stochastic SIS epidemic model incorporating media coverage in a two patch setting. Appl Math Comput. 2015;262:160–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo W., Cai Y., Zhang Q., Wang W. Stochastic persistence and stationary distribution in an SIS epidemic model with media coverage. Physica A. 2018;492:2220–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2017.11.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caraballo T., Fatini M.E., Pettersson R., Taki R. A stochastic SIRI epidemic model with relapse and media coverage. Discrete Contin Dyn Syst Ser B. 2018;23:3483–3501. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun C., Yang W., Arino J., Khan K. Effect of media-induced social distancing on disease transmission in a two patch setting. Math Biosci. 2011;230:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y., Cui J. The effect of constant and pulse vaccination on SIS epidemic models incorporating media coverage. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2009;14:2353–2365. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castillo-Chavez C., Feng Z., Huang W. In: Mathematical approaches for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases part i: an introduction to models, methods and theory. Castillo-Chavez C., Blower S., van den Driessche P., Kirschner D., editors. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2002. On the computation of and its role on global stability. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diekmann O., Heesterbeek J.A.P., Metz J.A.J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous population. J Math Biol. 1990;28:365–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji C., Jiang D., Shi N. Multigroup SIR epidemic model with stochastic perturbation. Physica A. 2011;390:1747–1762. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji C., Jiang D., Yang Q., Shi N. Dynamics of a multigroup SIR epidemic model with stochastic perturbation. Automatica. 2012;48:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berrhazi B., Fatini M.E., Caraballo T., Pettersson R. A stochastic SIRI epidemic model with Lévy noise. Discrete Contin Dyn Syst Ser B. 2018;23:2415–2431. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray A., Greenhalgh D., Hu L., Mao X., Pan J. A stochastic differential equation SIS epidemic model. SIAM J Appl Math. 2011;71:876–902. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W., Meng X., Dong Y. Periodic solution and ergodic stationary distribution of stochastic SIRI epidemic systems with nonlinear perturbations. J Syst Sci Complex. 2019;32:1104–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q., Jiang D., Hayat T., Ahmad B. Stationary distribution and extinction of a stochastic SIRI epidemic model with relapse. Stoch Anal Appl. 2018;36:138–151. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q., Jiang D., Hayat T., Alsaedi A. Influence of stochastic perturbation on an SIRI epidemic model with relapse. Appl Anal. 2020;99:549–568. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang W., Meng X. Stochastic analysis of a novel nonautonomous periodic SIRI epidemic system with random disturbances. Physica A. 2018;492:1290–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandyopadhyay M., Chattopadhyay J. Ratio-dependent predator-prey model: effect of environmental fluctuation and stability. Nonlinearity. 2005;18:913–936. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Asseldonk M.A.P.M., van Roermund H.J.W., Fischer E.A.J., de Jong M.C.M., Huirne R.B.M. Stochastic efficiency analysis of bovine tuberculosis-surveillance programs in the netherlands. Prev Vet Med. 2005;69:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nsuami M.U., Witbooi P.J. Stochastic dynamics of an HIV/AIDS epidemic model with treatment. Quaest Math. 2019;42:605–621. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahrouz A., Omari L., Kiouach D. Global analysis of a deterministic and stochastic nonlinear SIRS epidemic model. Nonlinear Anal Model Control. 2011;16:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caraballo T., Fatini M.E.I., Sekkak I., Taki R., Laaribi A. A stochastic threshold for an epidemic model with isolation and a non linear incidence. Commun Pure Appl Anal. 2020;19:2513–2531. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q., Jiang D. Stationary distribution and extinction of a stochastic SIR model with nonlinear perturbation. Appl Math Lett. 2017;73:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao X. Horwood Publishing; Chichester: 1997. Stochastic differential equations and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui J.-A., Tao X., Zhu H. An SIS infection model incorporating media coverage. Rocky Mount J Math. 2008;38:1323–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv X., Meng X., Wang X. Extinction and stationary distribution of an impulsive stochastic chemostat model with nonlinear perturbation. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2018;110:273–279. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Q., Jiang D., Hayat T., Ahmad B. Stationary distribution and extinction of a stochastic predator-prey model with additional food and nonlinear perturbation. Appl Math Comput. 2018;320:226–239. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Q., Jiang D., Hayat T., Ahmad B. Periodic solution and stationary distribution of stochastic SIR epidemic models with higher order perturbation. Physica A. 2017;482:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Has’minskii R.Z. Sijthoff Noordhoff, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands. 1980. Stochastic stability of differential equations. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng S., Zhu X. Necessary and sufficient condition for comparison theorem of 1-dimensional stochastic differential equations. Stoch Process Appl. 2006;116:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berman A., Plemmons R.J. Academic Press; New York: 1979. Nonnegative matrices in the mathematical sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higham D.J. An algorithmic introduction to numerical simulation of stochastic differential equations. SIAM Rev. 2001;43:525–546. [Google Scholar]