Abstract

The first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Iran were detected on February 19, 2020. Soon the entire country was hit with the virus. Although dermatologists were not immediately the frontline health care workers, all aspects of their practice were drastically affected. Adapting to this unprecedented crisis required urgent appropriate responses. With preventive measures and conserving health care resources being the most essential priorities, dermatologists, as an integral part of the health system, needed to adapt their practices according to the latest guidelines. The spectrum of the challenges encompassed education, teledermatology, lasers, and other dermatologic procedures, as well as management of patients who were immunosuppressed or developed drug reactions and, most importantly, the newly revealed cutaneous signs of COVID-19. These challenges have paved the way for new horizons in dermatology.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak started in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spread to other countries first in Asia and then worldwide.1 Iran was one of the first countries to be hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The first cases of COVID-19 in Iran were reported on February 19, 2020, although it seems that the virus had been circulating in the community for weeks.2 The number of diagnosed cases and the death toll rose exponentially in March and April; then the curve flattened and decreased to its nadir in late spring. Unfortunately, another surge began in late June, and the situation has continued to deteriorate.3, 4, 5

As of August 3, 2020, the official figures released by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran were 312,035 confirmed COVID-19 cases, 17,405 deaths, and 270,228 recovered patients.3 , 5 The true incidence should be much higher due to the high frequency of asymptomatic patients, low reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction testing capacity and sensitivity, poor sampling, lack of sampling of mildly symptomatic patients, and the stay-home policy.3 , 5

The outbreak of COVID-19 in Iran coincided with the end of the Persian year. Nowruz, or the Persian New Year feast, marks the beginning of the spring on March 21. March is characterized by a shopping spree and crowded streets, and the Nowruz holiday by family gatherings, ceremonies, and travels. All these events were demanding for a health system already overburdened by COVID-19.6

In the wake of the outbreak, public places, including schools and higher education institutions, were closed, and working hours were reduced. Stay-home and social distancing notices were issued.3 Most general hospitals in the hard-hit regions were designated for COVID-19. Specifically, dermatology wards in epicenters discharged their patients, and dermatology beds were allocated to COVID-19 and nondermatology patients in many major general hospitals. From the beginning of the outbreak, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education authorities continuously released specific protocols and their updates about proper implementations of dealing with COVID-19 for health care professionals. This was also directed to the general population based on the most recent data from the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.3

Dermatology practice

University practice

Although dermatologists have not been involved directly in the care of the critically ill and in-patient COVID-19 cases, dermatology practice has been considerably affected. Restrictions were placed on the dermatology wards; in some hospitals, dermatology wards and clinics were closed, and the beds were allocated to COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 emergency nondermatology patients. This, along with the reluctance of even severe patients to come to hospitals, have affected the care of dermatology patients, as well as the education of medical students and residents. General hospitals were no longer suitable for admission of the vulnerable dermatology patients who might be immunosuppressed. With the stay-home and lockdown policies, follow-ups became nonfunctional. The shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) and antiseptic liquids made the situation even worse.2 Considering the crowding in general hospitals, it was even difficult to adhere to social distancing.

Razi Hospital, a referral university skin hospital in the capital, minimized its activities to an active 24/7 emergency service, a general clinic, emergency patient admissions, and limited essential procedures.7 Due to controversies about the safety of biologic treatments,8 dermatology residents were asked to call patients who were candidates for inpatient biologic injection to postpone their appointment. In May 2020, after a significant decrease in the number of new cases, we gradually resumed inpatient biologic infusions, routine patient admissions, dermatologic surgeries, and later laser and esthetic procedures. With the decline of COVID-19 admissions, most dermatology wards and clinics were able to begin again their activity across the country, although in far less than in the pre-COVID-19 era.

Private practice

The activity of dermatologists became limited at the beginning of the outbreak despite the usual demand for esthetic and nonesthetic visits and procedures at that time of the year. This was due to both physicians’ and patients’ concerns related to viral exposure. During the annual holidays, private practices are usually closed. The reopening was allowed in early May 2020 with flattening of the curve. Practices were required to implement preventive measures, such as minimizing the number of patients in the waiting areas, observing at least 1.5 meters distance, screening for signs and symptoms of COVID-19, mandatory use of mask and gloves, nonallowance of companions for adult patients, regular hand-cleaning practice, removing possible sources of infections (such as drinking, newspapers, and magazines), and routine disinfection of the environment.9

Laser and esthetic clinics

Given the nonemergent nature of laser and esthetic procedures, these were suspended at the beginning of the outbreak.10 , 11 By decreasing the daily numbers of COVID-19 patients and relaxing the lockdown strategies, laser and esthetic clinics resumed their practice gradually according to the requirements released by Ministry of Health and Medical Education.3

Up to now, respiratory aerosols have been considered as the main source of transmission of COVID-19, and there is no evidence that laser-generated aerosols have any risk of infectivity.12 , 13 After the reopening of laser clinics, clients were being screened for possible signs and symptoms of COVID-19 by phone call before scheduling. Appointments were staggered to minimize the stay of patients in the waiting room. Besides the preventive measures, employing strict PPE procedures, proper air cleaners, and smoke evacuation became the least of the fundamental steps of reestablishing esthetic and laser clinics. Wearing a face mask is necessary for all the patients before, during, and after the procedure.9 , 14, 15, 16 Given the higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission during head and neck procedures, stricter use of protection is warranted.11

Surgery

Dermatologic surgery practice has been affected by the COVID-19 outbreak.16, 17, 18 Most elective outpatient surgical procedures were postponed or canceled to observe social distancing and preserve health care resources. An immediate implementation has been inevitable for urgent biopsies (for malignancies and severe diseases such as autoimmune bullous diseases) and surgical interventions for high-risk nonmelanoma skin cancers, melanoma, and infectious conditions (such as abscess drainage) due to the limited time threshold.14 , 19

As preventive measures, all the surfaces in the waiting and the surgery rooms are disinfected with sodium hydrochloride or alcoholic solutions, and hand sanitizers are available and used liberally.15 , 18 Some centers require a negative nasal reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction test 3 days before the procedure, whereas others consider it when suspicious signs, symptoms, or close contact with a COVID-19–positive patient exist. Another triage would be performed on the day of patients’ arrival and in case of any suspicion, infectious disease consultation should be obtained.

The operating rooms require efficient air filtration and adequate ventilation. If possible, a separate room was considered for suspicious or definite COVID-19 positive cases.15 The surgery was performed with the least necessary staff and with face masks, goggles, shoe covers, sterile disposable gloves, caps, and sterile gowns. Patients should also wear facemasks, shoe covers, and gowns. Given the theoretical presence of SARS-CoV-2 in electrosurgical smoke, using the lowest effective settings, high-efficacy filters, and smoke evacuators were recommended.15 , 16 , 18

Dermatoscopy

Dermatoscopy has become an indispensable tool for routine dermatology practice in recent years.20, 21, 22 With the emergence of COVID-19, dermatoscopes have been regarded as potential vectors of SARS-CoV-2.23 Physicians are becoming reluctant to use their handheld dermatoscopes considering the close distance needed for inspection. This issue is more concerning with head and neck lesions. Meanwhile, several ways are suggested for the safe use of this tool, such as using disposable caps, disinfection with alcohol wipes, and using glass slides, although most are not applicable in a busy outpatient clinic.20 , 21 , 23 In the few centers where videodermoscopes are available, these are becoming more popular among medical staff for selected patients to avoid close contact with the patient and better possibility of disinfection.23

Phototherapy

Phototherapy services were temporarily closed during the first few weeks of the outbreak but reopened later.7 , 24 In Iran, as worldwide, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy is the most popular form, and systemic psoralen plus ultraviolet A use is very limited. Ultraviolet A1 is unavailable. Excimer lamps/lasers are used occasionally when indicated.

Phototherapy is a relatively safe treatment in the COVID-19 era; however, the closed spaces of booths and high-touch areas may be a source of viral transmission.25 , 26 The need for commutes is another obstacle. To encourage social distancing, patients with nonurgent diseases were not suggested to choose this treatment option. Triage, staggered scheduling, and frequent application of sanitizers are highly suggested.25, 26, 27 Psoralen followed by sun exposure is an alternative option for those who do not want to attend phototherapy services; however, the risk of overexposure and burns should not be overlooked.24, 25, 26 Home phototherapy is also a well-tolerated modality, but it is not readily available.28

Medical education

Medical students

After the closure of education institutions, different forms of online classes have replaced face-to-face teaching and traditional classrooms.7 At the beginning of the outbreak, dermatology teaching for medical students was mainly performed through prerecorded lectures on PowerPoint, uploaded on platforms provided by the universities.27 Online slide conferences were also provided. These classes were not found to be optimal due to a lack of patient encounters. Although dermatology is a visually oriented field, other aspects of skin examination, including texture and temperature assessment, were missing.29 In some centers, in addition to these virtual classes, students were requested to attend in-person visits for efficient encounters with dermatology patients.

Interns

The medical interns’ presence and tasks were reduced in most dermatology rotations but not canceled. Although they are active in the emergency service and general clinics, their encounter with common dermatologic conditions such as hand dermatitis, acne, psoriasis, and lichen planus (LP) is reduced.7

Residents

Although face-to-face education has been completely canceled during the COVID-19 outbreak, it has been replaced with virtual classrooms.30 Journal clubs, clinicopathologic conferences, book reviews, and dermatopathology classes continued in this new format. Most junior residents were actively participating in the screening of emergency patients for COVID-19 whenever needed.7 Although in some teaching hospitals residents were redeployed to manage patients with COVID-19 at the peak of the pandemic, many residents, as well as some faculty members, took part voluntarily in this task to help overcome the medical staff shortage.31 Consultation for skin problems of admitted patients with COVID-19 has become another new responsibility in this era. The decline in dermatology patient visits in the clinics has affected residents’ education. Hands-on training for surgical and esthetic procedures has also become markedly limited during this period.7 The use of simulators (animal or commercial) would be a valuable option if lockdown continued.17

Teledermatology

Teledermatology has become a necessity with the surge of COVID-19, with stay-home and social distancing policies.32 , 33 The infrastructure is not widely present in Iranian practices, especially public and university facilities. Asynchronous store-and-forward e-visits and e-consults in popular social media platforms (WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram) are the most commonly used forms of teledermatology.34 , 35 The most important barriers to telehealth are the unclear legal status as a way of practicing medicine, lack of insurance coverage, and payment and prescription problems. New startups have been used in private sectors recently with promising results. Administrative teams of the national health systems are also actively working on the protocols of telemedicine, especially teledermatology, addressing medicolegal liabilities and privacy issues.

In some hospitals, although an online platform was not available, residents were proactively participating in teledermatology during the crisis by calling high-risk patients who had recently received biologics, immunosuppressants, and high doses of steroids as inpatients and those who were supposed to be admitted for decision making and rescheduling their biologic injections. The management plans were finalized by the attending faculty. These contacts were highly welcomed by patients. Those who were feeling isolated, abandoned, lonely, or frustrated were partly relieved by these calls. A 24/7 phone was allocated to these patients in case of any questions. Store-and-forward teledermatology using WhatsApp was also an indispensable tool in our everyday hospital practice.7

Teledermatology has its limitations; lack of access to professional platforms, poor internet quality, and patients’ low digital literacy are the most important.36 Other important drawbacks include the fact that sending high-quality pictures is not always possible due to the lack of a suitable device for image capturing and that patients are reluctant to send pictures of their bodies.36, 37, 38 Finally, teledermatology seems to be most suitable for follow-up visits39, 40, 41 or straightforward diagnoses or for a consult.42

The dermatology community

After the emergence of COVID-19, all seminars and conferences were canceled or postponed to an unspecified date; nevertheless, dermatologists remained strongly connected through social media; they updated their knowledge about COVID-19, shared their experiences, and took a fundraising initiative to support COVID-19- affected areas. Dermatologists have joined COVID-19 awareness campaigns in the social media platforms encouraging people to practice social distancing, stay home, perform hand hygiene, and wear face masks. Residents and dermatologists offered free online consultation through social media platforms (Instagram, WhatsApp). In a few weeks after the outbreak, national and international webinars and workshops rapidly replaced in-person events and are highly appreciated nowadays.

The Iranian Society of Dermatology participated in the distribution of PPE and other equipment to the hardest-hit provinces. The society also contributed to the preparation of guidelines for the safe reopening of practices. A special issue of the Iranian Journal of Dermatology, the official journal of the Iranian Society of Dermatology, was dedicated to COVID-19. The society has been very active in organizing regular national webinars.

Health care workers (HCWs) have a significantly increased risk of COVID-19 infection, and many of them lost their lives around the globe. The risk is highest for frontline HCWs who have a history of contact with known COVID-19 patients.43 In Iran, as of July 22, 2020, COVID-19 had taken the lives of more than 138 HCW.44 A number of dermatologists acquired the disease and one died.

New challenges

Hand dermatitis

Despite the global efforts to find well-tolerated and effective drugs and vaccines, hand hygiene adherence is still the most important measure in the fight against COVID-19.45 Frequent hydration and exposure to soaps, detergents, sanitizers, and alcohol-based disinfectants have increased the incidence of hand dermatitis. Various features from dryness to irritant contact dermatitis and even allergic contact dermatitis may be seen.46 Patients with preexisting skin problems, notably atopic dermatitis, and HCWs are more vulnerable.47 , 48 More frequent hand cleaning and wearing gloves for prolonged periods increase the susceptibility of the latter group.47 , 49 Prevention and management of hand dermatitis increase hand hygiene compliance significantly.50 The liberal application of moisturizers is the cornerstone of the management of this condition.49 , 51 , 52 After the emergence of COVID-19, complaints related to hand dermatitis, which is generally one of the most common causes of outpatients’ visits, became even more common.49 , 53 Hand dermatitis became a universal problem in the community. As in many other countries, Iranian dermatologists released instructions for the prevention and primary management of this condition. Besides in-person visits for the most severely affected, free e-visits were performed using various available platforms. Management of hand dermatitis was one of the most common uses of teledermatology in this era.49 , 50

Personal protective equipment

Given the highly contagious nature of SARS-CoV2, using PPE is considered indispensable for HCWs and caregivers to COVID-19 patients. The grade of recommendations depends on the hazard risk. For those working in COVID-19 wards and caring for intubated patients, full protective equipment, including double-layered gloves, N95 respirators, goggles or eye shields, and full gowns, is necessary.5 Wearing this equipment is hard to tolerate due to warmth and excess sweating. Skin changes are reported after long working hours in 97% of first-line health workers; the bridge of the nose, cheek, and forehead were the most commonly affected sites.47 Various tips and recommendations are suggested to decrease the side effects of PPE and increase their tolerance.54, 55, 56 In addition to irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and pressure-related skin injury, preexisting skin conditions such as acne, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, and delayed pressure urticaria may worsen.43 , 57 , 58 In addition, excess sweating is a predisposing factor for various superficial fungal or bacterial infections. Skin reactions markedly reduce the adherence to using PPE and the quality of health care. Dermatologists provided regular consultations to HCWs to mitigate PPE-related skin problems.

Over time and with the acquisition of new evidence about the routes of transmission of SARS-CoV2, global health authorities have updated their recommendations on the use of masks by the general public.5 Now that lockdown has been eased and wearing a mask is recommended especially in crowded, closed, and public areas, we are encountering mask-related skin problems in non-HCWs more often.

Drug reactions

At the beginning of the pandemic, the therapeutic management of COVID-19 was mostly based on anecdotal nonapproved findings. Antimalarials, especially hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), were the group of drugs that received the highest attention medically, socially, and politically.59 Iran was not exempt, and HCQ became the most commonly prescribed drug for the treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19. This surge in the demand led to a shortage of supply, and the temporary emergence of the black market for this controversial drug raised concern for rheumatology and dermatology patients who were on HCQ. On the other hand, HCQ-induced drug reactions became one of the challenges in dermatology practice. Acute generalized exanthematic pustulosis,60, 61, 62 Stevens-Johnson syndrome,63 maculopapular and urticarial rashes,64 drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome,65 and itching64 are known cutaneous reactions of HCQ. Another potential hazard is the exacerbation of psoriasis.66 Iranian dermatologists managed many patients with such reactions in e-visits, e-consults, in-person visits, dermatology wards, and COVID-19 services.63 There are recent reports regarding HCQ cardiotoxicity and questionable efficacy.67 , 68

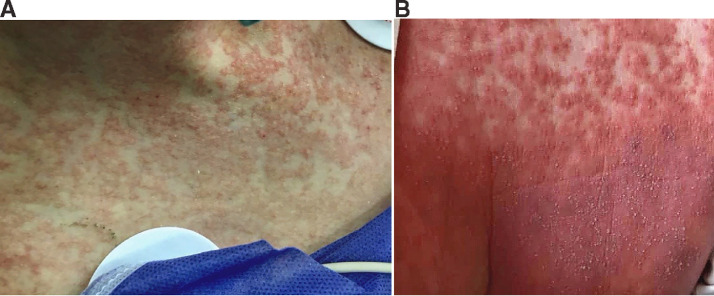

HCQ-induced acute generalized exanthematic pustulosis is particularly challenging because it may have a more variable morphology and a refractory course, unlike the usually self-limited nature of this rash due to other drugs.69 In some cases, besides systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs had been needed to control the reaction, a challenging issue in the COVID-19 era70 (Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Acute generalized exanthematic pustulosis due to hydroxychloroquine (A) in an intubated young woman with COVID-19; (B) a hospitalized man with COVID-19. (A, Courtesy Drs Nourmohammadpour and MolhemAzar, Razi Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; B, Dr. Goodarzi, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.)

A wide spectrum of drugs had been used since the emergence of COVID-19; some of them are now abandoned due to lack of efficacy, and a few are becoming more widely used.71 Many of them are associated with cutaneous reactions. Remdesivir is now the only drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration with promising efficacy.70 , 72 , 73 Of importance for dermatologists is the risk of skin rashes (8%) with this drug72; however, remdesivir is not yet widely available in Iran.

COVID-19-related skin changes

COVID-19-related skin changes are divided into two main groups: inflammatory/exanthematous and vasculopathic/vasculitic lesions. The first group includes an urticarial eruption, confluent erythematous/maculopapular/morbilliform eruption, and papulovesicular exanthem, and the second group encompasses chilblain-like acral pattern, livedo reticularis/racemose–like pattern, and purpuric “vasculitic” pattern.74 To the best of our knowledge, there is no published study about the incidence of skin manifestations of COVID-19 in Iran so far.75 , 76 In a small survey we asked dermatologists about their experience of cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 and directly contacted some who were working in COVID-19 hospitals. Their reported estimates were far less than the 20% reported from Italy.77 Maculopapular eruptions, urticaria (Figure 2 ),78 and pityriasis rosea (Figure 3 )79 were the most commonly encountered skin problems. Other reported findings were acral vasculitis/vasculopathy (Figure 4 ); livedoid vasculopathy lesions; vesicular herpetiform lesions (Figure 5 ); necrotic lesions; Kawasaki-like, disseminated zoster; small vessel vasculitis; pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions; pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta–like lesions; oral red macules; and oral aphthous-like lesions and vesicles.80, 81, 82 Severe telogen effluvium was also a common problem for patients after recovery.

Fig. 2.

Urticaria in a woman 1 week after recovery from mild COVID-19. (Courtesy Dr. Maboudi, Amol, Iran.)

Fig. 3.

Pityriasis rosea–like lesions on the thigh of a young woman. Most of her family members had COVID-19. (Courtesy Dr. Maboudi, Amol, Iran.)

Fig. 4.

Vasculopathic lesions of the limbs in a hospitalized man with COVID-19. (Courtesy Dr. Goodarzi, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.)

Fig. 5.

Extensive vesicular herpetiform lesions of the buttocks in an older hospitalized woman with COVID-19. (Courtesy Dr. Goodarzi, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.)

Chilblain-like lesions, or “COVID toes,” are another much-disputed entity in COVID-19 patients. This finding is especially reported in late stages and mild forms of COVID-19.83 , 84 In contrast to the high rate of reports of pernio-like lesions in European countries in early spring,85 , 86 “COVID toe” was identified rarely in Iran. More recent studies have questioned the direct relationship of chilblains and COVID-19.87, 88, 89 In a large series of patients with chilblain, the authors did not find any evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the large majority of patients with acral lesions.90

Dermatology patients and COVID-19

Dermatology patients who were receiving systemic corticosteroids, biologics, and traditional immunosuppressives are generally considered vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and severity.91, 92, 93 The challenging question of the early days of the pandemic was whether to continue these medications, how much each drug is considered tolerable, and how to assess the risks and benefits. No experience or evidence-based guideline was available in the literature except limited data from severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreaks.

Guidelines recommend discontinuing immunosuppressive drugs during active COVID-19 and using steroids at the lowest possible dose.8 , 92, 93, 94, 95 This strategy, as well as respiratory infection, may ensue with a disease flare-up.96, 97, 98 In noninfected patients, besides the controversies about systemic corticosteroids, the question was mainly focused on three categories of drugs that were available and widely used in Iran: tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (biosimilar etanercept; biosimilar adalimumab, and brand infliximab); anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (biosimilar rituximab), and Janus kinase inhibitors (tofacitinib).

Like our colleagues around the world, we soon adopted the policy to continue anti–tumor necrosis factor agents for our patients with psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa, the two main indications of this class of drugs, unless they had been infected with COVID-19.99 , 100 For psoriatic patients with no evidence of arthritis, acitretin is becoming more popular, and phototherapy, although well tolerated, is suggested with caution considering the need for thrice-weekly commutes. Cyclosporine and methotrexate are used with more caution, and in the case of COVID-19, their use is suspended until complete recovery from the infection.

Regarding hidradenitis suppurativa, antimicrobials and hormonal therapy are used routinely, whereas elective surgeries are better postponed to a time after relative control of the COVID-19 pandemic.101

Cutaneous LP is best managed with topical super potent corticosteroids; however, in the case of recalcitrant cutaneous LP, erosive mucosal LP, and lichen planopilaris using systemic steroids and immunosuppressives could be inevitable.102 , 103 Oral hydroxychloroquine is considered as the first-line systemic treatment in lichen planopilaris due to its safety profile in the COVID-19 era. Meanwhile, systemic retinoids such as oral isotretinoin could be also a well-tolerated and effective alternative.22 Similar to patients with psoriasis, conventional immunosuppressive drugs should be used with high vigilance, and in the case of COVID-19, they have to be held.

Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common autoimmune bullous disease in Iran,104 and its management may be challenging. Oral corticosteroids and rituximab are the main treatment options105, 106, 107, 108 despite their speculative risk.8 , 93 , 94, 117 Intravenous immunoglobulin is being used more often along with these two modalities in active moderate to severe forms of the disease, or cases of resistance or exacerbation after rituximab, for faster control of disease, using lower doses of steroids and rapid steroid tapering.109 , 110 Although not yet approved, intravenous immunoglobulin is a theoretically effective treatment for severe COVID-19, making its use more tempting.111 , 112 Given its milder immunosuppressive effects, lower doses of rituximab are being used more often. A few weeks after the outbreak began, the prescription of rituximab was resumed. Short-stay infusion units are preferred to dermatology wards for infusion of biologics. Although we consider rituximab for the treatment of moderate to severe patients with pemphigus and mucous membrane pemphigoid,113 maintenance or prophylactic doses are withheld as a rule. Broad-spectrum immunosuppressives are not generally prescribed unless necessary.94 On the other hand, bullous pemphigoid patients are being treated mostly by topical steroids and doxycycline; low doses of steroids are used in case of nonresponse,114 and intravenous immunoglobulin and rituximab are rarely needed.

Research

Although COVID-19 opened new horizons for research, ongoing prospective studies are disrupted. Social distancing and stay-home orders impeded the regular follow-ups of patients and patients’ recruitment. As of August 1, 2020, several publications on different dermatologic aspects of COVID-10 are already in PubMed from Iranian dermatologists, mostly as comments and case reports, and many more are under review.

Conclusions

COVID-19 is reshaping many aspects of dermatologic practice and education worldwide. Teledermatology should overcome the regulatory barriers and will be incorporated into our practice. This outbreak paves the way and even speeds up the reintegration of dermatology in health care.115 Dermatologists will collaborate across all kinds of borders.116 Ongoing COVID-19 clinical trials on interventions and vaccines may offer new hope and new challenges for dermatologists. Robust studies on the safety of present and future dermatologic agents during the pandemic will change our practice, and new evidence-based guidelines are anticipated.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Azadeh Goodarzi, Dr. Arash Maboudi, Dr. Pedram Nourmohammadpour, and Dr. Pedram MolhemAzar provided images of their patients.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salimi R, Gomar R, Heshmati B. The COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. J Glob Health. 2020;10 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Coronavirus epidemic in Iran. Available at: http://ird.behdasht.gov.ir/. Accessed August 3, 2020.

- 4.Venkatesan P. COVID-19 in Iran: round 2. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:784. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus2019. Accessed August 3, 2020.

- 6.Heidari M, Sayfouri N. Did Persian Nowruz aggravate the 2019 coronavirus disease crisis in Iran? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14 doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.178. e5-e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedini R, Ghandi N, Lajevardi V, Ghiasi M, Nasimi M. Dermatology department: what we could do amidst the pandemic of COVID-19? J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1773381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakshouk H, Daneshpazhooh M, Murrell DF, Lehman JS. Treatment considerations for patients with pemphigus during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.005. e235-e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cembrano KAG, Ng JN, Rongrungruang Y, Auewarakul P, Goldman MP, Manuskiatti W. COVID-19 in dermatology practice: getting back on track. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35:1871–1874. doi: 10.1007/s10103-020-03043-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emadi SN, Abtahi-Naeini B. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and dermatologists: potential biological hazards of laser surgery in epidemic area. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;198 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madan V. Resumption of laser/IPL skin services post COVID-19 lockdown—British Medical Laser Association (BMLA) guidance document. Lasers Med Sci. 2020;35:2069–2073. doi: 10.1007/s10103-020-03086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galadari H, Gupta A, Kroumpouzos G. COVID 19 and its impact on cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13822. doi: 10.1111/dth.13822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo O, Locatello LG. Laser-assisted head and neck surgery in the COVID-19 pandemic: controversial evidence and precautions. Head Neck. 2020;42:1533–1534. doi: 10.1002/hed.26271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Der Sarkissian SA, Kim L, Veness M, Yiasemides E, Sebaratnam DF. Recommendations on dermatologic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.034. e29-e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emadi SN, Ehsani AH, Balighi K, Nasimi M. Cosmetic surgeries amidst pandemic area of COVID-19: suggested protocol. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1790484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L, Song Z, Qian Y, Tao J. To resume outpatient dermatologic surgery safely during stabilized period of coronavirus disease-2019: experiences from Wuhan, China. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13522. doi: 10.1111/dth.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Lozano JA, Cuellar-Barboza A, Garza-Rodríguez V, Vázquez-Martínez O, Ocampo-Candiani J. Dermatologic surgery training during the COVID-19 era. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16621. e370-e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahiry AK, Grover C, Mubashir S. Dermatosurgery practice and implications of COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations by IADVL SIG Dermatosurgery (IADVL Academy) Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:333–336. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_237_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geskin LJ, Trager MH, Aasi SZ. Perspectives on the recommendations for skin cancer management during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:295–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldust M, Zalaudek I, Gupta A, Lallas A, Rudnicka L, Navarini AA. Performing dermoscopy in the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13506. doi: 10.1111/dth.13506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakhar D, Bhat YJ, Chatterjee M. Dermoscopy practice during COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations by SIG Dermoscopy (IADVL Academy) Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:343–354. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_231_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmoudi H, Rostami A, Tavakolpour S. Oral isotretinoin combined with topical clobetasol 0.05% and tacrolimus 0.1% for the treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia: a randomized controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1750553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakhar D, Kaur I, Kaul S. Art of performing dermoscopy during the times of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): simple change in approach can save the day! J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16412. e242-e244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, Gelfand JM. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguilera P, Gilaberte Y, Pérez-Ferriols A. Management of phototherapy units during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations of the AEDV's Spanish Photobiology Group. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:73–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacifico A, Ardigò M, Frascione P, Damiani G, Morrone A. Phototherapeutic approach to dermatology patients during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic: real-life data from the Italian red zone. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:375–376. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aghakhani K, Shalbafan M. What COVID-19 outbreak in Iran teaches us about virtual medical education. Med Educ Online. 2020;25 doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1770567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Türsen Ü, Türsen B, Lotti T. Ultraviolet and COVID-19 pandemic. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:2162–2164. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh TY, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. COVID-19 and its effect on medical student education in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.026. e163-e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider SL, Council ML. Distance learning in the era of COVID-19. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Science. Iran confronts coronavirus amid a “battle between science and conspiracy theories.” Available at: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/iran-confronts-coronavirus-amid-battle-between-science-and-conspiracy-theories. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- 32.Bhat YJ, Aslam A, Hassan I, Dogra S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on dermatologists and dermatology practice. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:328–332. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_180_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villani A, Scalvenzi M, Fabbrocini G. Teledermatology: a useful tool to fight COVID-19. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:325. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1750557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su MY, Lilly E, Yu J, Das S. Asynchronous teledermatology in medical education: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.033. e267-e268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams V, Kovarik C. WhatsApp: an innovative tool for dermatology care in limited resource settings. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:464–468. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakhtiar M, Elbuluk N, Lipoff JB. The digital divide: how Covid-19’s telemedicine expansion could exacerbate disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.043. e345-e346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Doan HQ. Teledermatology in the wake of COVID-19: advantages and challenges to continued care in a time of disarray. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:168–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okeke CAV, Shipman WD, Perry JD, Kerns ML, Okoye GA, Byrd AS. Treating hidradenitis suppurativa during the COVID-19 pandemic: teledermatology exams of sensitive body areas. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1781042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murrell DF, Lucky AW, Salas-Alanis JC. Multidisciplinary care of epidermolysis bullosa during the COVID-19 pandemic—consensus: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1222–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruggiero A, Megna M, Annunziata MC. Teledermatology for acne during COVID-19: high patients’ satisfaction in spite of the emergency. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16746. e662-e663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villani A, Annunziata MC, Abategiovanni L, Fabbrocini G. Teledermatology for acne patients: how to reduce face-to-face visits during COVID-19 pandemic. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1828. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farshchian M, Potts G, Kimyai-Asadi A, Mehregan D, Daveluy S. Outpatient teledermatology implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and lessons learned. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long H, Zhao H, Chen A, Yao Z, Cheng B, Lu Q. Protecting medical staff from skin injury/disease caused by personal protective equipment during epidemic period of COVID-19: experience from China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:919–921. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.TehranTimes. Coronavirus: 138 healthcare workers in Iran lose lives. Available at: https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/450361/Coronavirus-138-healthcare-workers-in-Iran-lose-lives. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 45.Ma QX, Shan H, Zhang HL, Li GM, Yang RM, Chen JM. Potential utilities of mask-wearing and instant hand hygiene for fighting SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1567–1571. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rundle CW, Presley CL, Militello M. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1730–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lan J, Song Z, Miao X. Skin damage among health care workers managing coronavirus disease-2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1215–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei S, Xue Y, Zhao S. Occupational skin conditions on the front line: a survey among 484 Chinese healthcare professionals caring for Covid-19 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16570. e354-e357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beiu C, Mihai M, Popa L, Cima L, Popescu MN. Frequent hand washing for COVID-19 prevention can cause hand dermatitis: management tips. Cureus. 2020;12:e7506. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Personal protective equipment recommendations based on COVID-19 route of transmission. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.068. e45-e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Araghi F, Tabary M, Gheisari M, Abdollahimajd F, Dadkhahfar S. Hand hygiene among health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and recommendations. Dermatitis. 2020;31:233–237. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blicharz L, Czuwara J, Samochocki Z. Hand eczema: a growing dermatological concern during the COVID-19 pandemic and possible treatments. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13545. doi: 10.1111/dth.13545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh M, Pawar M, Bothra A, Choudhary N. Overzealous hand hygiene during the COVID 19 pandemic causing an increased incidence of hand eczema among general population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.047. e37-e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atzori L, Ferreli C, Atzori MG, Rongioletti F. COVID-19 and impact of personal protective equipment use: from occupational to generalized skin care need. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13598. doi: 10.1111/dth.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gheisari M, Araghi F, Moravvej H, Tabary M, Dadkhahfar S. Skin reactions to non-glove personal protective equipment: an emerging issue in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16492. e297-e298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu N, Xiao Y, Su J, Huang K, Zhao S. Practical tips for using masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13555. doi: 10.1111/dth.13555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darlenski R, Tsankov N. COVID-19 pandemic and the skin: what should dermatologists know? Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:785–787. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Desai SR, Kovarik C, Brod B. COVID-19 and personal protective equipment: treatment and prevention of skin conditions related to the occupational use of personal protective equipment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:675–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alia E, Grant-Kels JM. Does hydroxychloroquine combat COVID-19? A timeline of evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.031. e33-e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohaghegh F, Jelvan M, Rajabi P. A case of prolonged generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by hydroxychloroquine: literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:2391–2395. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearson KC, Morrell DS, Runge SR, Jolly P. Prolonged pustular eruption from hydroxychloroquine: an unusual case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Cutis. 2016;97:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR) Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davoodi L, Jafarpour H, Kazeminejad A, Soleymani E, Akbari Z, Razavi A. Hydroxychloroquine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome in COVID-19: a rare case report. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1093/omcr/omaa042. omaa042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balamurugesan K, Davis P, Ponprabha R, Sarasveni M. Chloroquine induced urticaria: a newer adverse effect. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2545–2547. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_413_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grandolfo M, Romita P, Bonamonte D. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome to hydroxychloroquine, an old drug in the spotlight in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13499. doi: 10.1111/dth.13499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kutlu Ö, Metin A. A case of exacerbation of psoriasis after oseltamivir and hydroxychloroquine in a patient with COVID-19: will cases of psoriasis increase after COVID-19 pandemic? Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13383. doi: 10.1111/dth.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mazzanti A, Briani M, Kukavica D. Association of hydroxychloroquine with QTc interval in patients with COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142:513–515. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Generalized pustular figurate erythema: a newly delineated severe cutaneous drug reaction linked with hydroxychloroquine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13380. doi: 10.1111/dth.13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yalçın B, Çakmak S, Yıldırım B. Successful treatment of hydroxychloroquine-induced recalcitrant acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with cyclosporine: case report and literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:431–434. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Türsen Ü, Türsen B, Lotti T. Cutaneous sıde-effects of the potential COVID-19 drugs. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13476. doi: 10.1111/dth.13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nili A, Farbod A, Neishabouri A, Mozafarihashjin M, Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H. Remdesivir: A beacon of hope from Ebola virus disease to COVID-19. Rev Med Virol. 2020;30:1–13. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marzano AV, Cassano N, Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Vena GA. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19: a preliminary review of an emerging issue. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:431–442. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1236520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seirafianpour F, Sodagar S, Mohammad AP. Cutaneous manifestations and considerations in COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13986. doi: 10.1111/dth.13986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387. e212-e213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Najafzadeh M, Shahzad F, Ghaderi N, Ansari K, Jacob B, Wright A. Urticaria (angioedema) and COVID-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16721. e568-e570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ehsani AH, Nasimi M, Bigdelo Z. Pityriasis rosea as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16579. e436-e437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aghazadeh N, Homayouni M, Sartori-Valinotti JC. Oral vesicles and acral erythema: report of a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1153–1154. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shahidi Dadras M, Zargari O, Abolghasemi R, Bahmanjahromi A, Abdollahimajd F. A probable atypical skin manifestation of COVID-19 infection. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1791309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tehranchinia Z, Asadi-Kani Z, Rahimi H. Lichenoid eruptions with interface dermatitis and necrotic subepidermal blister associated with COVID-19. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13828. doi: 10.1111/dth.13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71–77. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C. Chilblain-like lesions during COVID-19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16526. e291-e293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Suarez-Valle A. Characterization of acute acral skin lesions in nonhospitalized patients: a case series of 132 patients during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.093. e61-e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, Aguirre T. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739–743. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herman A, Peeters C, Verroken A. Evaluation of chilblains as a manifestation of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:998–1003. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hernandez C, Bruckner AL. Focus on “COVID toes.”. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1003. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roca-Ginés J, Torres-Navarro I, Sánchez-Arráez J. Assessment of acute acral lesions in a case series of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:992–997. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Cleach L, Dousset L, Assier H. Most chilblains observed during the COVID-19 outbreak occur in patients who are negative for COVID-19 on PCR and serology testing. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:866–874. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Louapre C, Collongues N, Stankoff B. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1079–1088. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nobari NN, Goodarzi A. Patients with specific skin disorders who are affected by COVID-19: what do experiences say about management strategies? A systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13867. doi: 10.1111/dth.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Price KN, Frew JW, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. COVID-19 and immunomodulator/immunosuppressant use in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.046. e173-e175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kasperkiewicz M, Schmidt E, Fairley JA. Expert recommendations for the management of autoimmune bullous diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16525. e302-e303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ghalamkarpour F, Pourani MR, Abdollahimajd F, Zargari O. A case of severe psoriatic erythroderma with COVID-19. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1799918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nasiri S, Araghi F, Tabary M, Gheisari M, Mahboubi-Fooladi Z, Dadkhahfar S. A challenging case of psoriasis flare-up after COVID-19 infection. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:448–449. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1764904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ebrahimi A, Sayad B, Rahimi Z. COVID-19 and psoriasis: biologic treatment and challenges. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1789051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Georgakopoulos JR, Mufti A, Vender R, Yeung J. Treatment discontinuation and rate of disease transmission in psoriasis patients on biologic therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic—a Canadian multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1212–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Torres T, Puig L. Managing cutaneous immune-mediated diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Babahosseini H, Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H. Lichen planopilaris: retrospective study on the characteristics and treatment of 291 patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:598–604. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1542480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H, Abedini R, Kamyab Hesari K, Kiani A, Daneshpazhooh M. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: an update on the hypothesis of pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Daneshpazhooh M, Chams-Davatchi C, Payandemehr P, Nassiri S, Valikhani M, Safai-Naraghi Z. Spectrum of autoimmune bullous diseases in Iran: a 10-year review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Daneshpazhooh M, Balighi K, Mahmoudi H. Iranian guideline for rituximab therapy in pemphigus patients. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e13016. doi: 10.1111/dth.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Joly P, Maho-Vaillant M, Prost-Squarcioni C. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux 3): a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2031–2040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murrell DF, Peña S, Joly P. Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: recommendations of an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.021. 575-585.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Toosi R, Mahmoudi H, Balighi K. Efficacy and safety of biosimilar rituximab in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: a prospective observational study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:33–40. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1617831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mahmoudi H, Balighi K, Tavakolpour S, Daneshpazhooh M. Unexpected worsening of pemphigus vulgaris after rituximab: a report of three cases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;71:40–42. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nili A, Tavakolpour S, Mahmoudi H, Noormohammadpour P, Balighi K, Daneshpazhooh M. Paradoxical reaction to rituximab in patients with pemphigus: a report of 10 cases. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2020;42:56–58. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2020.1717526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Daneshpazhooh M, Soori T, Isazade A, Noormohammadpour P. Mucous membrane pemphigoid and COVID-19 treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: a case report. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:446–447. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1764472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pourahmad R, Moazzami B, Rezaei N. Efficacy of plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IVIG) on patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Amir Dastmalchi D, Moslemkhani S, Bayat M. The efficacy of rituximab in patients with mucous membrane pemphigoid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1801974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Azimi SZ, Firooz A, Murrell DF, Daneshpazhooh M. Treatment concerns for bullous pemphigoid in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13956. doi: 10.1111/dth.13956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goldust M, Sharma A, Murrell DF. Dermatology and specialty rotations: COVID-19 may reemphasize the importance of internal medicine. Dermatol Ther. 2020:e13996. doi: 10.1111/dth.13996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goldman MP, Murrell DF, Al-Mutairi N. International collaboration. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:757. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1794290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mahmoudi H, Salehi Farid A, Nili A. Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune bullous diseases: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.043. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]