Sir

On 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020) and the government of India imposed lockdown restrictions from 25th March 2020 (Dore, 2020). Healthcare services were geared towards saving lives and handling COVID services at the cost of routine healthcare. Child care and support are bearing the brunt of the pandemic as in any disaster and may leave long lasting effects on children’s psyche (Danese et al., 2020; Green, 2020).

With forced home stay and loss of contact with teachers, friends, trainers and counsellors, children are under stress and are losing opportunity for healthy growth and learning. Many children are unable to get the nutrition from meals which they were earlier getting in the schools (Witt et al., 2020). Recent research has documented harmful effects of outbreak of COVID-19 on children’s mental health (Duan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). However, the effect of lockdown and school closure could have positive effect on children’s mental health. The resulting decrease in academic and social stress could be a boon for children by reducing their life-stressors imposed by modern lifestyle of rigid schooling and immense academic pressure (Bruining et al., 2020)

We evaluated the impact of lockdown and school closure caused by COVID-19 situation on mental well-being, behaviour, screen media use of children diagnosed with psychiatric disorders and seeking care from a specialized Child and Adolescent Psychiatry services of a tertiary care medical centre in eastern India. We also assessed the need as well as the barriers in accessing specialized child psychiatry services.

This was a cross sectional telephonic interview -based study from 1st June 2020 to 8th July 2020. Of 881 patients called on telephone, 225 responded. We prepared a semi-structured interview schedule based on Kidscreen 27, Swanson Nolan Pelham (SNAP-IV), World Mental Health Survey Barriers to Service Scale for this study.

Verbal Consent was taken from participating parents after informing about the purpose of the study and Ethical approval was taken from Institute Ethics Committee.

Mean age of the children was 10.96 years, 140(62.22 %) were males, 180 (80 %) were attending regular schools. Mean age of the parents was 38 years, 69(30.67 %) had attained intermediate level of education, 63(28 %) were graduates, 59(26.22 %) had received some school education. Higher proportion of parents were skilled workers and professionals 63(28 %), 31(13.78 %) were engaged in their own business, 47 (20.89 %) were semi-skilled and unskilled workers, 67(29.78 %) were housewives and 11 (4.89 %) were students.

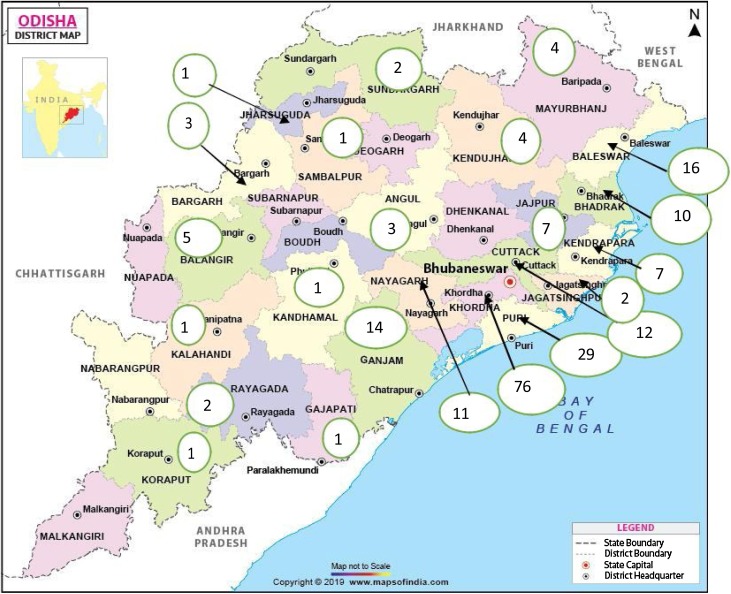

The distribution of the study participants as per their domicile districts of Odisha is depicted in Fig. 1 . Out of 225 participants, 76 (33.78 %) belonged to Khordha district, people from far off districts like Koraput and Rayagada had also responded. For ease of analysis, we clubbed the various childhood diagnoses into six broad diagnostic categories: (i) Developmental disorders which included Mental Retardation and Disorders of Psychological Development;(ii) Emotional disorder which included: mixed disorders of conduct and emotions, emotions disorders with onset specific to childhood, and tic disorder; (iii) Behavioral disorders including Hyperkinetic disorders and Conduct disorder; (iv) Somatic symptoms; (v) Dissociative Disorder and (vi) Seizure disorders.

Fig. 1.

District of domicile of participants.

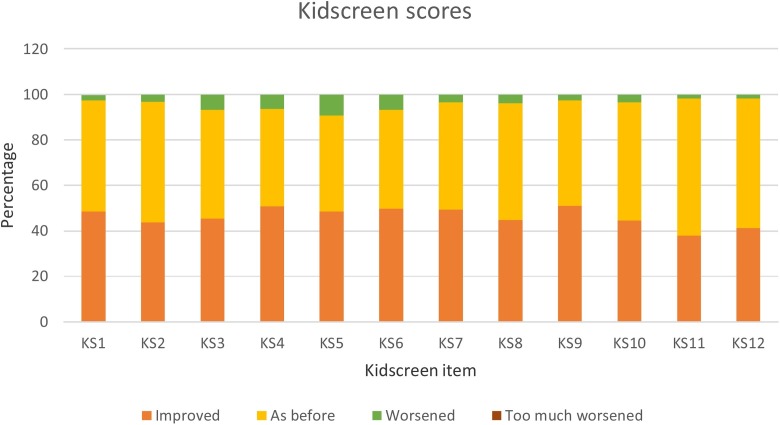

Child subjective health in domains of physical, psychological health were reported by majority of parents as improved or as before COVID-19 period (>90 %). Parents of only a small percentage of children reported deterioration in psychological well- being: 9% parents reported their children were not in ‘good mood’ and 7% reported their children no longer had fun (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Children’s subjective well-being scores.

Parent rated Child Behaviour showed change during the COVID-19 period. While majority of parents reported improvement and behaviour remaining as before COVID-19 period, a small minority of parents reported worsening of child behaviour in the domains of ‘anger (30 %)’ and ‘inability to keeps the adult uninterrupted (15 %).’ Too much worsening was seen in around 3 percent of children in the domains of ‘neatness ability’ and ‘eating behaviour’ of SNAP IV.

Upon closure of schools as per government of Odisha directives, online classes are being provided by the schools. 28 % parents reported their children were attending online classes and found these classes helpful. 62 % parents reported that their children were using Screen Media for other activities. They also perceived that there was increase in Screen Media use by their children and felt this was harmful for their children. 37.33 % of parents perceived Screen Media causing behavioral harm to their children. The harmful effects of increased screen media use on cognition is known and experts suggest limiting screen media access by children (Hutton et al., 2020).

58 % parents reported need for specialized child psychiatry services for their child. There were various barriers in seeking care: fear of contracting COVID-19, lockdown, financial difficulties and geographical distance. Majority (53 %) reported fear of contracting COVID-19, followed by 45 % reporting lockdown as reason for not being able to come for consultation. With 58 % of parents reporting need for specialist psychiatry services suggests adequate awareness about child psychiatric symptoms and available provisions for treatment. COVID-19 fear has seriously hampered treatment seeking by parents with obvious harmful consequences.

This is the first study from India reporting on child mental health during COVID-19 pandemic. Our study design had included potentially positive as well as negative effect of lockdown and school closure on children’s well-being. None of the parents reported being in isolation or quarantine due to COVID-19 hence the data here is not related to psychological distress related to COVID-19 infection.

Our results point towards the positive effect of lockdown and school closure on children’s mental health (Bruining et al., 2020). This can be explained by the fact that this unique situation has increased time for family life for children which they are perceiving in a positive manner. Also, closure of school could mean decrease in academic stress resulting in better sense of well-being. The densely populated rural areas of India precluded strict enforcement of lockdown which means children could go out and play in the neighbourhoods which could have contributed towards their wellness. We did not find any association of worsening of behavioural problems with diagnostic category which is contrary to available findings (Zhang et al., 2020).

The improved sense of wellbeing and behaviours in children during the COVID-19 lockdown and school closure has provided a unique opportunity to understand the various factors which act as stressors with a detrimental impact on child mental health. Studies with robust research methodology can help improve current understanding of these risk factors. COVID-19 has provided unprecedented opportunity to re-strategize healthcare and research to serve humanity (Tandon, 2020).

References

- Bruining H., Bartels M., Polderman T., Popma A. COVID-19 and child and adolescent psychiatry: an unexpected blessing for part of our population? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01578-5. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A., Smith P., Chitsabesan P., Dubicka B. Child and adolescent mental health amidst emergencies and disasters. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2020;216(3):159–162. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore B. Covid-19: collateral damage of lockdown in India. BMJ. 2020;369:m1711. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L., Shao X., Wang Y., Huang Y., Miao J., Yang X., Zhu G. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. Risks to children and young people during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:m1669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton J.S., Huang G., Sahay R.D., DeWitt T., Ittenbach R.F. A novel, composite measure of screen-based media use in young children (ScreenQ) and associations with parenting practices and cognitive abilities. Pediatr. Res. 2020;87(7):1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R. COVID-19 and mental health: preserving humanity, maintaining sanity, and promoting health. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt A., Ordóñez A., Martin A., Vitiello B., Fegert J.M. Child and adolescent mental health service provision and research during the Covid-19 pandemic: challenges, opportunities, and a call for submissions. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2020;14:19. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Shuai L., Yu H. Acute stress, behavioural symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 9] Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;(51):102077. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]