Abstract

Introduction

Barrier enclosure devices were introduced to protect against infectious disease transmission during aerosol generating medical procedures (AGMP). Recent discussion in the medical community has led to new designs and adoption despite limited evidence. A scoping review was conducted to characterize devices being used and their performance.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of formal databases (MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CENTRAL, Scopus), grey literature, and hand-searched relevant journals. Forward and reverse citation searching was completed on included articles. Article/full-text screening and data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers. Studies were categorized by publication type, device category, intended medical use, and outcomes (efficacy – ability to contain particles; efficiency – time to complete AGMP; and usability – user experience).

Results

Searches identified 6489 studies and 123 met criteria for inclusion (k = 0.81 title/abstract, k = 0.77 full-text). Most articles were published in 2020 (98%, n = 120) as letters/commentaries (58%, n = 71). Box systems represented 42% (n = 52) of systems described, while plastic sheet systems accounted for 54% (n = 66). The majority were used for airway management (67%, n = 83). Only half of articles described outcome measures (54%, n = 67); 82% (n = 55) reporting efficacy, 39% (n = 26) on usability, and 15% (n = 10) on efficiency. Efficacy of devices in containing aerosols was limited and frequently dependent on use of suction devices.

Conclusions

While use of various barrier enclosure devices has become widespread during this pandemic, objective data of efficacy, efficiency, and usability is limited. Further controlled studies are required before adoption into routine clinical practice.

Keywords: Barrier enclosure, Protected intubation, Aerosol box, AGMP, COVID-19

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the threat of diminishing supplies of personal protective equipment sparked an interest in alternative means to protect healthcare providers. One such means included barrier enclosure devices, which are generally described as a plastic sheet over a structural frame or a transparent plastic four-sided box that are used as a potential method of protecting healthcare providers from SARS-CoV-2 during aerosol generating medical procedures (AGMP) (e.g. intubation or extubation). This device is typically placed in between a patient and airway operator during an AGMP as a means of physically limiting the transmission of aerosols and/or droplets to healthcare providers.

Currently there is limited evidence to support the use of barrier enclosure devices and important questions remain regarding their efficacy in reducing contamination, efficiency of use, and usability within various healthcare settings. In May 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a temporary emergency medical device license for the use of protective barrier enclosures [1]. While healthcare institutions continue to test, modify, and adopt these barriers into practice, we sought to collate and characterize the published literature on devices that are being used in various settings, as well as elucidate any performance outcomes (i.e., efficacy, efficiency, usability) associated with each system. A scoping review was selected given the heterogeneity of the literature on this topic.

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying relevant studies

A protocol of our methodology was published a priori and followed PRISMA-ScR guidelines [2,3]. A search to identify barrier enclosure devices was executed by an academic information specialist in bibliographic databases including Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Scopus (2000-01-01 to 2020-06-24) for the main concepts of AGMPs and barrier enclosure devices (Appendix A) across all languages. The year 2000 was chosen to capture barrier devices potentially used during previous pandemics (e.g., SARS-CoV-1). We excluded non-human studies, conference and book materials. Additionally, a grey literature search of Google Scholar, clinical trials registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO Clinical Trials), pre-print repositories (OSF, MedRvix), disseminated reports (Canadian Agency for Drug Technologies in Canada, World Health Organization, National Health Service, Public Health Agency of Canada, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) was performed. Relevant journals in emergency medicine (American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, British Medical Journal – Emergency Medicine), anesthesiology (Anesthesia, Anesthesia & Analgesia, British Journal of Anesthesia, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, Journal of Clinical Anesthesia), and otolaryngology (Head & Neck and Ear, Nose & Throat Journal) were manually searched on 2020-07-03 reviewing articles published in March to July 2020 issues and those available as early release. Forward and reverse citation searching was completed on all included articles (2020-07-19). All citations were managed in Covidence (covidence.org) screening software.

2.2. Study selection

Two reviewers (CP, DT) independently evaluated the eligibility of studies on the basis of title and/or abstract using pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ). A sample of 100 articles were screened to ensure consistency among reviewers and fidelity of established criteria. Reviewers independently evaluated the eligibility of all articles; disagreements were resolved by re-evaluation, discussion, and when necessary, in consultation with a third reviewer. Full-text articles were retrieved if reviewers considered a citation potentially relevant. Reviewer agreement for study eligibility was assessed using the unweighted Cohen's kappa coefficient.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1) Descriptions, design, and/or protocol for barrier enclosure use in AGMPsa 2) All article types (e.g. original research, reviews) 3) Any publication status (e.g., pre-print, online) 4) Time frame: 2000–2020-06-24 5) Studies in: humans, experimental, simulation 6) Any language |

1) Conference abstracts, posters or proceedings, registered trials, online website material 2) Critique or opinion on prior published work, with no introduction of a new device 3) Non-infectious risk exposure (e.g. chemotherapy, radiation) |

Defined as any enclosure which surrounds the patient and aims to prevent droplet spread and aerosol dispersion into the environment during an intervention.

2.3. Charting the data

Data abstraction was completed independently by one reviewer (CP) using a standardized form (Appendix B) and verified by a second reviewer (DT, JC, MBY). We abstracted publication details (author, title, publication date, country of origin, publication status, publication type), setting, device design details, intended medical use, methods and outcomes. A list and definition of variables collected can be found in Appendix B.

2.4. Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Devices were categorized as either a box, plastic sheet (with frame), plastic sheet (without frame), or other system. Outcomes, both qualitative and quantitative, were categorized as either efficacy (i.e., related to the device's ability to protect the intubator and contain particles), efficiency (i.e., time taken to perform an AGMP) or usability metrics (i.e., feedback on experience of the use of the system).

3. Results

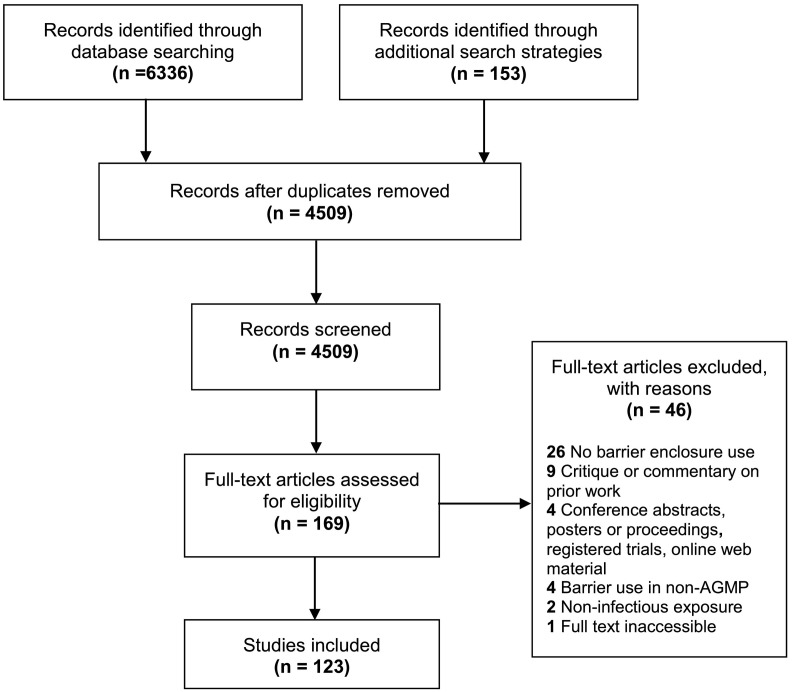

A total of 6336 articles were identified through formal database search strategies, and 153 articles through grey literature and citation screening (Fig. 1 ). After duplicate removal, 4509 unique articles were screened, and 169 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. We identified 123 articles for inclusion. Our kappa coefficient was good for title/abstract screening (kappa = 0.81) and full-text review (kappa = 0.77).

Fig. 1.

Barrier system study selection.

Most articles were published between March 2020 – July 2020 (n = 120), with three articles published prior to 2020 [[4], [5], [6]]. Over half of articles were published as letters/commentaries (58%, n = 71), 29% as original research studies (n = 36), and 13% (n = 16) as brief/short reports. Publications originated from 27 unique countries with the top 3 countries including the United States (34%, n = 42), India (10%, n = 12), and Canada (10%, n = 12).

3.1. Device design

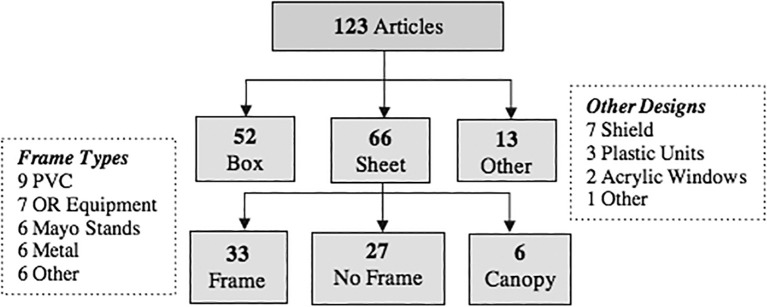

Commonly reported barrier enclosure devices include box (42%, n = 52) and plastic sheet (54%, n = 66) systems. Over half (59%, n = 39/66) of plastic sheet systems utilized a supportive frame and 41% (n = 27/66) had no supportive structure (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Barrier device designs.

Note: 8 articles discussed the use of multiple device types13, 20, 21, 24, 39, 87, 98, 99. 1PVC = polyvinyl chloride. 2OR = operating room. 3Plastic Units = large non-mobile chambers fully enclosing the patient.

Box designs were often similar to the original design in Canelli et al. [7], which is a transparent 4-sided structure with two open faces: an inferior face bound by the stretcher and a caudal face pointed towards the foot of the bed. Common modifications included change in the number or size of ports (i.e., for operators and/or tools) [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]], increased device size for improved operator ergonomics and/or patient body habitus [[13], [14], [15]], built-in gloves and/or port coverings [11,12,16,17], addition of a plastic drape or covering on the caudal face [[18], [19], [20]], a sloped top panel for improved visibility [15,18,21] and the use of a negative suction system [[22], [23], [24]].

Conversely, plastic sheet systems with frames were constructed using polyvinyl chloride tubing [25,26], operating room equipment (e.g., anesthetic screens) [24,27], and Mayo stands [28,29]. Six articles introduced a plastic canopy system, which is semicircular in shape enclosing the patient's upper or full body [4,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34]]. Alternatively, plastic sheet systems without a frame were often akin to surgical draping, where a clear sheet drapes over the patient's head, neck and/or entire body and the physician works beneath the drape or cuts an opening into the plastic sheet [5,[35], [36], [37]].

There were a number of other unique designs. Three articles introduced large, non-mobile plastic chamber units for COVID-19 testing [38,39] and outpatient ENT procedures [40] in which the patient entered the closed system and the procedure was performed through two ports. Seven articles described shield structures (e.g. 1 or 2-faced plastic stand or board). [21,[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]

3.2. Intended medical use/medical context

The most commonly reported use was for airway management (67%, n = 83) (Table 2 ). Within these, 84% reported use for intubation or extubation (n = 70/83), 7% (n = 6/83) for tracheostomies [23,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51]], and 6% (n = 5/83) for non-invasive respiratory support (e.g. high-flow nasal cannula) [26,30,34,52,53]. Two studies (2%, n = 2/83) used a device in pediatric laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy [54,55]. Nine studies (7%) discussed these devices for general AGMPs [22,25,32,46,[56], [57], [58], [59], [60]] and 9 (7%) for endoscopic procedures. [10,11,43,45,[61], [62], [63], [64]]

Table 2.

Summary of barrier devices by category, intended use, and purpose of publication

| Device category | Intended medical use | Total | Objective |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | Evaluation | ||||

|

Description: 4-sided transparent plastic box. Typically includes 2 ports for the provider and/or assistant. |

Airway Management | Intubation/Extubation (38)a Tracheostomy (1) Bronchoscopy & Laryngoscopy (1) |

40 | 33 (83%) | 23 (58%) |

| Endoscopica | Endoscopy (5) | 5 | 5 (100%) | 3 (60%) | |

| Surgical | Craniotomy (1) | 1 | 1 (100%) | 1 (100%) | |

| AGMPs (General) | AGMPs (General) (3) | 3 | 3 (100%) | 2 (67%) | |

| Other | Dental (1) Dermatology (1) Regional Anesthesia (2) |

4 | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Total | 52 | 44 (85%) | 30 (58%) | ||

|

Plastic Sheet (Frame, No Frame, Canopy) Description: Clear plastic sheet draped over a rigid frame or sheet placed directly on the patient during a procedure. |

Airway Management | Intubation / Extubation (36) Respiratory Support (5) Tracheostomy (5) Bronchoscopy & Laryngoscopy (1) |

47 | 43 (91%) | 23 (49%) |

| Endoscopic | Endoscopic (2) | 2 | 2 (100%) | – | |

| Surgical | ENT Procedures (7) Other Surgery (5) |

12 | 10 (83%) | 8 (67%) | |

| AGMPs (General) | AGMPs (General) (5) | 5 | 5 (100%) | 5 (100%) | |

| Total | 66 | 60 (91%) | 36 (55%) | ||

|

Other Description: devices include – 3 large plastic units, 2 acrylic windows, 7 shield-like structures and 1 inverted face tent (other). |

Airway Management | Intubation / Extubation (3) | 3 | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) |

| Endoscopic | Endoscopic (2) | 2 | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | |

| AGMPs (General) | AGMPs (General) (1) | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | |

| Other | Outpatient ENT (1) Sampling (5) Dental (1) |

7 | 7 (100%) | 1 (14%) | |

| Total | 13 | 13 (100%) | 6 (46%) | ||

| TOTAL | 123⁎ | 110 (89%) | 67 (54%) | ||

Note: 8 articles discuss the use of multiple device types. 6 were discussing a box & plastic sheet system, 1 box & other, and 1 other & plastic sheet. These articles have been counted in their respective groups in category counts and only once in the summary total count.

Study discusses dual-purpose use of the box for endoscopic procedures and airway management. Definitions: Descriptive = Description or device modification; Evaluation = Study includes an evaluation of device (qualitative or quantitative).

A small proportion of studies (11%, n = 14) used an enclosure during surgical procedures, mainly for otolaryngology procedures (57%, n = 8/14) (e.g. mastoidectomy, endo-nasal/endo-oral procedures) [40,[65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71]] as well as in other types of surgery (43%, n = 6/14) (e.g. craniotomy, oral maxillofacial, colorectal surgery) [5,6,[72], [73], [74], [75]]. Other uses included dental procedures [41,76], dermatological procedures [29], and regional anesthesia [9,77] (4%, n = 5/123).

3.3. Evaluation

Over half of articles included an evaluation component (54%, n = 67), the majority of which only included qualitative outcomes (54%, n = 36/67). Among these, 70% (n = 47) of studies reported on the use of enclosures in simulation settings, 19% (n = 13) reported their use in real patients, and 10% (n = 7) reported on use in both environments. Efficacy was the most frequently reported outcome among articles (82%, n = 55/67) followed by usability (39%, n = 26/67) and efficiency (15%, n = 10/67).

3.3.1. Efficacy

The most common method to assess the device's ability to contain particles or prevent contamination was through the visual assessment of droplets or smoke (71%, n = 39/55), primarily with box systems (51%, n = 20/39). Four studies used the ability to smell [78,79] or taste a bitter solution [60,80] as a proxy for aerosols escaping into the environment. Using these qualitative methods, studies concluded that the use of a barrier device was effective at either preventing or reducing the number of particles escaping the system.

Only 40% (n = 22/55) studies reported quantitative results. Three of these studies used pre-established grids to quantify exposure outside of the enclosure with fluorescent dye or gross droplets and reported success in reducing contamination [13,49,81]. Two studies reported no SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of physicians after using the system [59,82], while another four studies detected the presence of molecules contained within the enclosure and/or a decrease in particles outside the enclosure as a proxy for its effectiveness [5,6,34,74].

The majority of barriers (77%, n = 17/22) with objective findings used suction to generate negative pressure and reported particle counts or aerosol clearance rates (59%, n = 13/22) (Table 3 ). In contrast to the visual contamination studies showing effectiveness, evidence from quantitative data was often less favourable and contingent on the use of suction devices. For example, Simpson et al. [24] evaluated the efficacy of four different designs – a box, sealed box (caudal end closed), and two plastic sheet barrier systems and found that only when suction was applied, particle counts decreased. Similar results were seen in in Lyaker et al. with increased particle detection outside the chamber without the use of suction [83].

Table 3.

Efficacy – Quantitative results, review of particle counter studies

| Study | Device & methods | Comparators/Interventions | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box | |||

| Lyaker, US83 | Airway Management. Particle generator placed inside/outside enclosure. | 1-wall suction vs. 2-wall suction vs. No Suction | Particle detection outside the chamber increased above the ambient level without suction. Suction reduced the counts. |

| Brar, UK23 | Tracheostomy. Vaporizer generated particles with counters outside the enclosure. | Device vs. no device / Suction vs. no Suction | Decrease in particles detected at the position of the surgeon with the device and a reduction in the number of particles over time. |

| Hellman, US58 | AGMPs. Particle generator and a particle counter inside enclosure. | Hospital suction / commercially available suction / none | Aerosol clearance was significantly hastened with suction vs. passive clearance and the commercial suction device was better than in-hospital system. |

| Perella, UK22 | AGMPs. Simulated cough with normal breath measured through a particle generator. | Suction position /device openings/suction flow rate / device vs. no device | Device prevented particle escape. Optimal condition was when the suction was vertically next to the patient's head. |

| Le, US95 | Airway Management. Atomizer used to simulate aerosol production with counter inside/outside enclosure. | None listed | Containment of greater than 90% of sub-micrometer particles across all particle sizes. |

| Plastic Sheet | |||

| Lang, US57 | AGMPs. Humidifier generated particles with particle counters placed inside/outside enclosure. | Device vs. no device / Suction vs. no suction | Particle count detected outside hood significantly decreased with the system. Suction system reduced particle count inside the enclosure. |

| Shaw, US52 | Respiratory Support. Humidifier generated particles with particle counters placed inside/outside enclosure. Nasal cannula used inside hood. | Smoke evacuator 60%/80%/100%/Off | Particle count outside and inside the hood decreased with the use of smoke evacuator. |

| Bryant, US96 | Airway Management. Particle generator placed inside enclosure. Counter measured inside & outside enclosure. | Complete closure, arms inserted, enclosure with flaps open and closed. All vs. suction. | Greatest reduction in particles was with the enclosure closed using suction and highest concentrations when the flap was open. There was no change in particles concentrations with the front flap was open. |

| Bassin, US32 | Canopy. AGMPs. Particle generator inside hood with counters placed inside/outside enclosure. | HFNC, Nebulizer, CPAP with / without particle generator | No detectable increase in room air particle counts. |

| Chari, US66 | Surgical. Mastoidectomy performed on a cadaver. Spectrometer measured particles 30 cm from site. | 2 barrier drape designs with/without suction | No drape, no barrier drape + suction, barrier drape without suction had high particle counts. Original drape with suction, modified barrier drape, and modified barrier drape with suction showed no increase. |

| Milne, Canada97 | Airway Management. Flow rate testing completed with two suction sources. | Surgical suction sources vs. in-hospital wall suction | Theoretical times for airborne contaminant at 99% and 99.9% would be faster with the in-hospital suction system due to higher flow rates. |

| Adir, Israel30 | Respiratory Support. Face velocity and smoke direction of air measured perpendicular to hood. Photometry used for particle leakage. | None listed | The average air flow velocity was 4.4 m·s − 1 with the smoke flowing into the back side of the canopy. Filtration efficiency was reported at 0.0006%. |

| Multiple Device Types | |||

| Simpson, Australia24 | Box & Plastic Sheet. Airway Management. Nebulized saline through a simulated cough with particle counter outside enclosure. | Box / vertical drape / horizontal drape / sealed box with suction / sealed box without suction | The sealed intubation box with suction resulted in a decrease in almost all particle sizes across all time periods. The box had an increase in particle exposure. No difference using the plastic drapes. |

3.3.2. Usability

Usability was assessed primarily by self-reported qualitative feedback from physicians using these devices (81%, n = 21/26). Generally, authors reported success carrying out procedures using the device with no major issues, [33,44,54,61,75,77,84] however four studies using the box system reported additional workflow complexities [85] and challenges while performing intubation. [12,86,87]

Six articles included a quantitative assessment of usability for intubation (23%, n = 6/26, 4, 12, 88–91], mainly in the box (83%, n = 5/6) [12,[88], [89], [90], [91]] and one in a plastic sheet system (canopy) (17%, n = 1/6) [4]. Seger et al. reported a limited increase in time required for device maneuverability: removal and disposal within 10 s, and completion of a position change within the enclosure in less than 2 s. [91] However, Clariot et al. [88], Begley et al. [12], and Hamal et al. [89] reported worsening laryngoscopic views when using a box system. Similarly, Serdinšek et al. [90] and Plazikowski et al. [4] both reported more difficulty with airway management when using box and plastic canopy systems.

3.3.3. Efficiency

The most frequent efficiency metric reported was time to intubation or related metrics to securing an airway (e.g., first-pass success) (70%, n = 7/10, 4, 12, 88–92] primarily in the box system (86%, n = 6/7) [12,[88], [89], [90], [91], [92]]. Those assessing intubation times (40%, n = 4/10) noted increased time to intubation using the box system. [12,[88], [89], [90]] In Clariot et al., median tracheal intubation was longer (53 s vs. 48 s, p < 0.01) compared to no system. [88] Similarly, in Begley et al., comparison of two box systems to no barrier system increased time to intubation by 48 s and 28 s seconds, respectively [12]. First-pass success when using barrier systems was variable. While Plazikowski et al. [4] and Begley et al. [12] reported lower first-pass success when using plastic canopy and box systems, others noted no intubation failures or challenges with box systems. [88,[90], [91], [92]]

3.3.4. Box vs. sheet system comparisons

Five articles compared the box and plastic sheet systems [13,20,21,24,87]. In Brown et al. [87], Ibrahim et al. [20]., and Gore et al. [21], particles escaped through the open caudal end of box systems with increased contamination of the operator and/or environment relative to the plastic systems during airway management. Laosuwan et al. also assessed droplet contamination on a standardized grid in an extubation simulation and similarly reported increased contamination with box systems relative to plastic sheet systems [13]. Simpson et al. found that there was no significant difference in particle exposure outside the enclosure when comparing plastic sheet systems to no system during intubation, whereas the use of the box system concentrated particles without limiting dispersion [24]. Only one study compared usability between a box and plastic sheet system and reported that physicians favoured the plastic sheet system due to ease of mobility and the ability to accommodate an airway assistant [87].

4. Discussion

Barrier enclosures are described as innovative systems which protect healthcare workers from infectious disease transmission. We identified 123 articles from 27 countries, the majority of which were published following the original aerosol box design released in April 2020 [7]. Across these studies, three general device types were identified: box, plastic sheet with frame, and plastic sheet without frame systems for use in airway management (intubation, extubation, tracheostomies or respiratory support) or general aerosolizing medical procedures.

To date, there is a lack of strong evidence to support the use of barrier systems in clinical settings. Our review demonstrated a reliance on short letters/commentaries to validate various devices' medical use and safety and limited rigorous trials. Currently, evidence to support the reduction of aerosol and droplet contamination is based primarily on visual assessments of aerosol and droplet spread. While these results are generally positive, emerging quantitative studies have reported less favourable results that frequently depend on concurrent use of a suction device [24,83]. Often discussed as a low-cost, pragmatic means of protecting physicians, use of the box systems in some instances demonstrated a delay in time to intubation [12,88] and worsening laryngoscopic views [12,88,89], which has important clinical implications in physiologically difficult intubations. In fact, while simplistic, plastic sheet systems appear to outperform box systems in efficacy and usability characteristics, with less environmental contamination [13,24] and better ergonomics [87].

These variable characteristics are important to consider in light of the evolving SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In May 2020, the United States FDA granted emergency approval for barrier enclosure device manufacturing, distribution and use during AGMPs without guidance on the design or intended medical uses for these devices [1]. Subsequently, a plethora of various devices were heavily promoted through social media, press and in many medical journals translating to a large uptake of these systems [93] despite limited scientific evidence on efficacy, efficiency and usability. Recognizing this risk, the FDA has since revoked its emergency license for barrier enclosures devices in August 2020 [1], and now recommends the use of enclosures with suction devices in keeping with emerging objective evidence. [12,24]

The pandemic has highlighted the delicate balance of thorough evaluation with the need for immediate solutions. Commercial medical devices undergo rigorous testing in order to prove efficacy and safety for the patient and physician and requires strict reporting of adverse events through a centralized system to make decisions regarding continued use [94]. This is an opportunity for regulatory bodies to reexamine how emergency approvals are granted, and to set up infrastructure to encourage local innovation while providing a platform to register and monitor its effects, similar to how trials are registered.

In light of the established characteristics and performance outcomes, researchers and innovators looking to further develop and optimize barrier enclosures should focus on quantitative assessments of efficacy, efficiency, and usability in real clinical environments. Other opportunities for further exploration include focusing on patient-centered outcomes, such as frequency of desaturations and peri-intubation cardiac arrest, as well as the economics associated with implementation, wide-spread adoption, and maintenance (e.g., sterilization) of these devices.

5. Limitations

Our review focused on the published literature related to the use of barrier enclosure devices and did not include designs that were published on websites, social media or design sites. While devices published in non-academic mediums may have been missed in our scoping review, we believe this further highlights the need for a central platform to catalog and regulate the use of barrier enclosures. We also performed the last formal search on 2020-06-24 and were unable to obtain the full text of one study. As a rapidly growing field of research, other studies published since that time were not included in this review. However, forward and reverse citation screening on included articles was completed.

Many of these enclosure systems were devised in the early stages of the pandemic when things were rapidly evolving with many unknowns. As a consequence of that, the studies largely included qualitative and simulation-derived data on process measures. It will be important to perform quantitative studies analyzing real-world outcome (e.g. infectivity rates) in order to make any conclusions on the efficacy of these devices.

6. Conclusions

The use of barrier systems in clinical care was introduced to protect physicians during AGMPs. However, the efficacy of barrier enclosures in protecting physicians is limited. Overall, clinical use of these devices in the absence of thorough medical device testing is concerning and contrary to regulatory legislation intended to safeguard patient and physician safety.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Appendix A: Sample Database Search Strategy

Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to June 24, 2020>.

| Search history sorted by search number ascending | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | Searches | Results | Type |

| 1 | Autopsy/ | 41,987 | Advanced |

| 2 | Bronchoscopy/ | 25,070 | Advanced |

| 3 | exp “Nebulizers and Vaporizers”/ | 11,291 | Advanced |

| 4 | exp Aerosols/ | 31,294 | Advanced |

| 5 | exp Airway Management/ | 114,940 | Advanced |

| 6 | exp Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation/ | 17,926 | Advanced |

| 7 | exp Oxygen Inhalation Therapy/ | 25,828 | Advanced |

| 8 | exp Respiratory Function Tests/ | 233,679 | Advanced |

| 9 | exp Respiratory Therapy/ | 114,316 | Advanced |

| 10 | exp Ventilators, Mechanical/ | 9044 | Advanced |

| 11 | Laryngoscopy/ | 12,643 | Advanced |

| 12 | Suction/ | 12,404 | Advanced |

| 13 | Thoracostomy/ | 1453 | Advanced |

| 14 | Aerosol*.mp. | 55,689 | Advanced |

| 15 | AGMP?.mp. | 24 | Advanced |

| 16 | (Airway* adj2 control*).mp. | 1736 | Advanced |

| 17 | (Airway* adj2 manage*).mp. | 9341 | Advanced |

| 18 | (Airway* adj2 manipulat*).mp. | 231 | Advanced |

| 19 | (Airway adj2 surger*).mp. | 754 | Advanced |

| 20 | (artificial adj2 respirat*).mp. | 49,345 | Advanced |

| 21 | Aspirat*.mp. | 114,006 | Advanced |

| 22 | Atomizer*.mp. | 749 | Advanced |

| 23 | (Autopsy adj3 lung?).mp. | 819 | Advanced |

| 24 | Bioaerosol*.mp. | 1500 | Advanced |

| 25 | BiPAP.mp. | 670 | Advanced |

| 26 | Bronchoscop*.mp. | 39,004 | Advanced |

| 27 | (cardiac adj2 life support*).mp. | 1980 | Advanced |

| 28 | code blue.mp. | 240 | Advanced |

| 29 | CPAP.mp. | 8377 | Advanced |

| 30 | Cpr.mp. | 12,426 | Advanced |

| 31 | (Dental adj3 procedure*).mp. | 4780 | Advanced |

| 32 | Extubat*.mp. | 13,695 | Advanced |

| 33 | HFOV.mp. | 737 | Advanced |

| 34 | (high flow adj2 oxygen*).mp. | 710 | Advanced |

| 35 | (High frequency adj3 oscillat*).mp. | 3833 | Advanced |

| 36 | (High speed adj2 device*).mp. | 167 | Advanced |

| 37 | (High-speed adj2 drill*).mp. | 388 | Advanced |

| 38 | (Inhalation adj2 device*).mp. | 605 | Advanced |

| 39 | (Inhalation adj2 therap*).mp. | 16,350 | Advanced |

| 40 | Inhalator*.mp. | 692 | Advanced |

| 41 | (Insert* adj2 chest tube*).mp. | 869 | Advanced |

| 42 | Intubat*.mp. | 84,407 | Advanced |

| 43 | Ippb.mp. | 296 | Advanced |

| 44 | Ippv.mp. | 731 | Advanced |

| 45 | Laryngoscop*.mp. | 22,075 | Advanced |

| 46 | (Lung adj2 function test*).mp. | 3992 | Advanced |

| 47 | (Nasal cannula adj2 therap*).mp. | 316 | Advanced |

| 48 | Nasopharyngoscop*.mp. | 488 | Advanced |

| 49 | Ncpap.mp. | 1086 | Advanced |

| 50 | Nebuli?er*.mp. | 11,985 | Advanced |

| 51 | (Oral adj2 surger*).mp. | 12,381 | Advanced |

| 52 | (Pharyngeal adj2 surger*).mp. | 379 | Advanced |

| 53 | (physiotherapy* adj3 chest).mp. | 871 | Advanced |

| 54 | (Positive adj2 Airway Pressure*).mp. | 13,879 | Advanced |

| 55 | (Positive end adj2 expiratory pressure*).mp. | 5925 | Advanced |

| 56 | (positive adj2 pressure breath*).mp. | 1385 | Advanced |

| 57 | (positive adj2 pressure respirat*).mp. | 17,429 | Advanced |

| 58 | (Pulmonary adj2 function test*).mp. | 12,273 | Advanced |

| 59 | respirator*.mp. | 570,255 | Advanced |

| 60 | (Respiratory adj2 therap*).mp. | 9846 | Advanced |

| 61 | (Resuscitat* adj2 cardiopulmonary).mp. | 24,366 | Advanced |

| 62 | (Sputum adj3 induc*).mp. | 3258 | Advanced |

| 63 | Suction*.mp. | 26,595 | Advanced |

| 64 | (Thoracic adj2 surger*).mp. | 29,352 | Advanced |

| 65 | Thoracoscop*.mp. | 18,348 | Advanced |

| 66 | Thoracostom*.mp. | 2939 | Advanced |

| 67 | (Thorax adj2 drain*).mp. | 60 | Advanced |

| 68 | Tracheostom*.mp. | 16,396 | Advanced |

| 69 | Tracheotomy.mp. | 11,400 | Advanced |

| 70 | (Transphenoidal adj2 surger*).mp. | 155 | Advanced |

| 71 | Vapori?er*.mp. | 10,231 | Advanced |

| 72 | ventilat*.mp. | 186,237 | Advanced |

| 73 | Videolaryngoscop*.mp. | 1173 | Advanced |

| 74 | or/1–73 | 1,237,644 | Advanced |

| 75 | (Acrylic adj3 barrier*).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 76 | (Acrylic adj3 box*).mp. | 43 | Advanced |

| 77 | (Acrylic adj2 cover*).mp. | 61 | Advanced |

| 78 | (Acrylic adj3 drap*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 79 | (Acrylic adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 80 | (Acrylic adj3 hood?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 81 | (Acrylic adj3 screen?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 82 | (Acrylic adj3 sheet?).mp. | 54 | Advanced |

| 83 | (Acrylic adj3 shield*).mp. | 27 | Advanced |

| 84 | (Acrylic adj3 system*).mp. | 129 | Advanced |

| 85 | (Acrylic adj3 tarp?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 86 | (Acrylic adj2 unit?).mp. | 32 | Advanced |

| 87 | (Aerosol adj3 cover*).mp. | 34 | Advanced |

| 88 | (Aerosol adj2 evacuation system?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 89 | (Aerosol* adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 90 | (Aerosol* adj2 evacuation system?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 91 | (Aerosol* adj3 barrier*).mp. | 26 | Advanced |

| 92 | (Aerosol* adj3 box*).mp. | 22 | Advanced |

| 93 | (Aerosol* adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 94 | (Aerosol* adj3 screen?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 95 | (Aerosol* adj3 shield*).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 96 | (Aerosol* adj3 tent*).mp. | 10 | Advanced |

| 97 | (Aerosol adj2 unit?).mp. | 27 | Advanced |

| 98 | (Barrier adj2 device?).mp. | 217 | Advanced |

| 99 | (Barrier adj2 measure?).mp. | 394 | Advanced |

| 100 | (Barrier adj3 box*).mp. | 12 | Advanced |

| 101 | (Barrier adj2 cover*).mp. | 118 | Advanced |

| 102 | (Barrier adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 12 | Advanced |

| 103 | (Barrier adj3 hood?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 104 | (Barrier adj3 screen?).mp. | 40 | Advanced |

| 105 | (Barrier adj3 sheet*).mp. | 37 | Advanced |

| 106 | (Barrier adj3 shield*).mp. | 75 | Advanced |

| 107 | (Barrier adj3 system?).mp. | 1163 | Advanced |

| 108 | (Clear adj2 barrier*).mp. | 93 | Advanced |

| 109 | (Clear adj2 box*).mp. | 35 | Advanced |

| 110 | (Clear adj2 cover*).mp. | 78 | Advanced |

| 111 | (Clear adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 112 | (Containment adj2 chamber?).mp. | 14 | Advanced |

| 113 | (Containment adj2 device?).mp. | 69 | Advanced |

| 114 | (Containment adj2 unit?).mp. | 25 | Advanced |

| 115 | (Corona* adj2 curtain*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 116 | (Disposable adj3 barrier*).mp. | 30 | Advanced |

| 117 | (Disposable adj3 box*).mp. | 11 | Advanced |

| 118 | (Disposable adj2 cover*).mp. | 63 | Advanced |

| 119 | (Disposable adj3 drap*).mp. | 70 | Advanced |

| 120 | (Disposable adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 121 | (Disposable adj3 film?).mp. | 44 | Advanced |

| 122 | (Disposable adj3 hood?).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 123 | (Disposable adj3 screen?).mp. | 257 | Advanced |

| 124 | (Disposable adj3 sheet?).mp. | 24 | Advanced |

| 125 | (Disposable adj3 shield*).mp. | 39 | Advanced |

| 126 | (Disposable adj3 tarp?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 127 | (Disposable adj3 tent*).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 128 | (Disposable adj2 unit?).mp. | 86 | Advanced |

| 129 | (Drape* adj2 cover*).mp. | 29 | Advanced |

| 130 | (Droplet adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 131 | (Droplet adj2 evacuation system?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 132 | (Glass adj3 barrier*).mp. | 64 | Advanced |

| 133 | (Glass adj3 box*).mp. | 66 | Advanced |

| 134 | (Glass adj2 cover*).mp. | 2041 | Advanced |

| 135 | (Glass adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 8 | Advanced |

| 136 | (Glass adj3 screen?).mp. | 83 | Advanced |

| 137 | (Glass adj3 shield*).mp. | 44 | Advanced |

| 138 | (Glass adj2 unit?).mp. | 49 | Advanced |

| 139 | (Intubation adj3 barrier*).mp. | 8 | Advanced |

| 140 | (Intubation adj3 box*).mp. | 12 | Advanced |

| 141 | (Intubation adj3 cover*).mp. | 11 | Advanced |

| 142 | (Intubation adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 143 | (Intubation adj3 screen?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 144 | (Intubation adj3 shield*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 145 | (Intubation adj3 tent*).mp. | 3 | Advanced |

| 146 | (Intubation adj2 unit?).mp. | 79 | Advanced |

| 147 | (Isolat* adj2 chamber*).mp. | 340 | Advanced |

| 148 | (Isolat* adj2 container*).mp. | 12 | Advanced |

| 149 | (Isolat* adj2 cover*).mp. | 371 | Advanced |

| 150 | (Isolat* adj2 drape*).mp. | 11 | Advanced |

| 151 | (Isolat* adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 15 | Advanced |

| 152 | (Isolat* adj2 hood*).mp. | 32 | Advanced |

| 153 | (Isolat* adj2 tent*).mp. | 256 | Advanced |

| 154 | (Isolat* adj2 unit?).mp. | 1325 | Advanced |

| 155 | (Negative pressure adj3 cover*).mp. | 16 | Advanced |

| 156 | (Negative pressure adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 157 | (Patient adj2 covering).mp. | 188 | Advanced |

| 158 | (Physical adj3 barrier*).mp. | 5128 | Advanced |

| 159 | (Physical adj3 box*).mp. | 61 | Advanced |

| 160 | (Physical adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 9 | Advanced |

| 161 | (Physical adj3 screen?).mp. | 755 | Advanced |

| 162 | (Physical adj3 shield*).mp. | 60 | Advanced |

| 163 | (Physical adj2 unit?).mp. | 400 | Advanced |

| 164 | (Plastic adj3 barrier*).mp. | 108 | Advanced |

| 165 | (Plastic adj3 box*).mp. | 249 | Advanced |

| 166 | (Plastic adj3 cover*).mp. | 1068 | Advanced |

| 167 | (Plastic adj3 drap*).mp. | 108 | Advanced |

| 168 | (Plastic adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 24 | Advanced |

| 169 | (Plastic adj2 film?).mp. | 1031 | Advanced |

| 170 | (Plastic adj3 hood?).mp. | 20 | Advanced |

| 171 | (Plastic adj3 screen?).mp. | 30 | Advanced |

| 172 | (Plastic adj3 sheet?).mp. | 426 | Advanced |

| 173 | (Plastic adj3 shield*).mp. | 72 | Advanced |

| 174 | (Plastic adj3 system?).mp. | 633 | Advanced |

| 175 | (Plastic adj3 tarp?).mp. | 16 | Advanced |

| 176 | (Plastic adj3 tent*).mp. | 25 | Advanced |

| 177 | (Plastic adj2 unit?).mp. | 344 | Advanced |

| 178 | (Plexiglass adj3 barrier*).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 179 | (Plexiglass adj3 box*).mp. | 19 | Advanced |

| 180 | (Plexiglass adj3 cover*).mp. | 12 | Advanced |

| 181 | (Plexiglass adj3 drap*).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 182 | (Plexiglass adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 3 | Advanced |

| 183 | (Plexiglass adj3 hood?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 184 | (Plexiglass adj3 screen?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 185 | (Plexiglass adj3 sheet?).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 186 | (Plexiglass adj3 shield*).mp. | 7 | Advanced |

| 187 | (Plexiglass adj3 system?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 188 | (Plexiglass adj3 tarp?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 189 | (Plexiglass adj2 unit?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 190 | (Polycarbonate adj3 barrier*).mp. | 3 | Advanced |

| 191 | (Polycarbonate adj3 box*).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 192 | (Polycarbonate adj3 cover*).mp. | 27 | Advanced |

| 193 | (Polycarbonate adj3 drap*).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 194 | (Polycarbonate adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 195 | (Polycarbonate adj3 hood?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 196 | (Polycarbonate adj3 screen?).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 197 | (Polycarbonate adj3 sheet?).mp. | 39 | Advanced |

| 198 | (Polycarbonate adj3 shield*).mp. | 7 | Advanced |

| 199 | (Polycarbonate adj3 system?).mp. | 30 | Advanced |

| 200 | (Polycarbonate adj3 tarp?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 201 | (Polycarbonate adj2 unit?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 202 | (Polymer adj3 barrier*).mp. | 151 | Advanced |

| 203 | (Polymer adj3 box*).mp. | 11 | Advanced |

| 204 | (Polymer adj3 cover*).mp. | 347 | Advanced |

| 205 | (Polymer adj3 drap*).mp. | 1 | Advanced |

| 206 | (Polymer adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 207 | (Polymer adj3 hood?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 208 | (Polymer adj3 screen?).mp. | 42 | Advanced |

| 209 | (Polymer adj3 sheet?).mp. | 321 | Advanced |

| 210 | (Polymer adj3 shield*).mp. | 66 | Advanced |

| 211 | (Polymer adj3 system?).mp. | 3501 | Advanced |

| 212 | (Polymer adj3 tarp?).mp. | 0 | Advanced |

| 213 | (Polymer adj2 unit?).mp. | 213 | Advanced |

| 214 | (Portable adj2 barrier*).mp. | 7 | Advanced |

| 215 | (Portable adj2 box*).mp. | 35 | Advanced |

| 216 | (Portable adj2 cover*).mp. | 7 | Advanced |

| 217 | (Portable adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 6 | Advanced |

| 218 | (Portable adj2 hood*).mp. | 5 | Advanced |

| 219 | (Protect* adj2 intubation?).mp. | 56 | Advanced |

| 220 | (Protect* adj2 unit?).mp. | 387 | Advanced |

| 221 | (Protect* adj3 barrier*).mp. | 4549 | Advanced |

| 222 | (Protect* adj3 box*).mp. | 109 | Advanced |

| 223 | (Protect* adj3 cover*).mp. | 1367 | Advanced |

| 224 | (Protect* adj3 drap*).mp. | 46 | Advanced |

| 225 | (Protect* adj3 enclosure*).mp. | 25 | Advanced |

| 226 | (Protect* adj3 hood?).mp. | 59 | Advanced |

| 227 | (Protect* adj3 screen?).mp. | 200 | Advanced |

| 228 | (Protect* adj3 sheet?).mp. | 76 | Advanced |

| 229 | (Protect* adj3 shield*).mp. | 889 | Advanced |

| 230 | (Protect* adj3 tarp?).mp. | 2 | Advanced |

| 231 | (Protect* adj3 tent*).mp. | 47 | Advanced |

| 232 | (Tent adj2 cover*).mp. | 4 | Advanced |

| 233 | (Transparent adj2 barrier*).mp. | 74 | Advanced |

| 234 | (Transparent adj2 box*).mp. | 58 | Advanced |

| 235 | (Transparent adj2 cover*).mp. | 110 | Advanced |

| 236 | (Transparent adj2 enclosure*).mp. | 5 | Advanced |

| 237 | or/75–236 | 31,062 | Advanced |

| 238 | 74 and 237 | 1699 | Advanced |

| 239 | limit 238 to yr = “2000 -Current” | 1330 | Advanced |

| 240 | animals/ not (animals/ and humans/) | 4,677,410 | Advanced |

| 241 | 239 not 240 | 1192 | Advanced |

| 242 | remove duplicates from 241 | 1183 | Advanced |

Appendix B: Data abstraction form with variable definitions

| Data field | Definition |

|---|---|

| Publication details | |

| Study Title | Full article title. |

| Publication Date | Date of first publication. If online, indicated the date the article was first available. |

| Primary Author | First author listed. |

| Publication Status | Status at the time of data abstraction. Options: Published: Peer Reviewed; Pre-Print Server; Pre-Proof; Other |

| Publication / Article Type | Options: Letter to The Editor, Original Research, Commentary, Brief Report, Opinion/Editorial, Other |

| Country | Country where the study took place, or where the study was published from (corresponding author's location). |

| Setting | Options: ED/Critical Care, Surgical/Draping, GI/ENT Procedures, Non-Emergent Airway Management (e.g. general OR procedures), Other |

| Study Category |

Options:

|

| Device Details | |

| Device Description | Design details of all the device (e.g. # of drapes, different size / shapes, coverage provided) and any unique features included. |

| Device Category |

Options:

|

| Intended Medical Use | Actual use or intended medical use of the device. If describing a device for “general use”, but no procedure specified, list “AGMPs”. Options: intubation, extubation, tracheostomy, endoscopy, bronchoscopy, NIPPV, ENT surgeries (e.g. endonasal / endo-oral), dental procedures, other (free-text) |

| Evaluation & Results | |

| Study Design Type | Study design type, if applicable and available. |

| Patient Population | Description of the patient population in the study. |

| Methods | Study participants, sample size and method of measurements. |

| Study Outcomes | Listed outcomes for efficacy, efficiency, usability, and other. |

| Results | Main results of each study outcome(s). |

| Limitations | Main study limitations as listed by the author(s) |

References

- 1.U.S. Food & Drug Administration Protective Barrier Enclosures Without Negative Pressure Used During the COVID-19 Pandemic May Increase Risk to Patients and Health Care Providers - Letter to Health Care Providers. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/letters-health-care-providers/protective-barrier-enclosures-without-negative-pressure-used-during-covid-19-pandemic-may-increase; accessed August 31 2020.

- 2.Price C, Tawadrous D, Ben-Yakov M, Orchanian-Cheff A, Choi J. Barrier enclosure use during aerosol-generating medical procedures: a scoping review protocol. OSF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plazikowski E., Greif R., Marschall J., Pedersen T.H., Kleine-Brueggeney M., Albrecht R., et al. Emergency airway Management in a Simulation of highly contagious isolated patients: both isolation strategy and device type matter. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(2):145–151. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Putzer D., Lechner R., Coraca-Huber D., Mayr A., Nogler M., Thaler M. The extent of environmental and body contamination through aerosols by hydro-surgical debridement in the lumbar spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137(6):743–747. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nogler M., Lass-Florl C., Wimmer C., Bach C., Kaufmann C., Ogon M. Aerosols produced by high-speed cutters in cervical spine surgery: extent of environmental contamination. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(4):274–277. doi: 10.1007/s005860100310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canelli R., Connor C.W., Gonzalez M., Nozari A., Ortega R. Barrier enclosure during endotracheal intubation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1957–1958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vijayaraghavan S., Puthenveettil N. Aerosol box for protection during airway manipulation in covid-19 patients. Indian J. Anaesthesia. 2020;64(14 Supplement 2):S148–S149. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_375_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaichandran V.V., Raman R. Aerosol prevention box for regional anaesthesia for eye surgery in COVID times. Eye. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-1027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mcleod R.W.J., Warren N., Roberts S.A. Development and evaluation of a novel protective device for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the COVID-19 pandemic: the EBOX. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traina M., Amata M., Granata A., Ligresti D., Gaetano B. The C-Cube: an endoscopic solution in the time of COVID-19. Endoscopy. 2020 doi: 10.1055/a-1190-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begley J.L., Lavery K.E., Nickson C.P., Brewster D.J. The aerosol box for intubation in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: an in-situ simulation crossover study. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laosuwan P., Earsakul A., Pannangpetch P., Sereeyotin J. Acrylic Box Versus Plastic Sheet Covering on Droplet Dispersal During Extubation in COVID-19 Patients. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):e106–e108. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik J.S., Jenner C., Ward P.A. Maximising application of the aerosol box in protecting healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(7):974–975. doi: 10.1111/anae.15109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girgis A.M., Aziz M.N., Gopesh T.C., Friend J., Grant A.M., Sandubrae J.A., et al. Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Aerosolization Box: Design Modifications for Patient Safety. J. Cardiothoracic Vascular Anesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marquez-Gde V.J., Lopez Bascope A., Valanci-Aroesty S. Low-cost double protective barrier for intubating patients amid COVID-19 crisis. Anesthesiology. 2020;05:05. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahmoune F.C., Ben Yahia M.M., Hajjej R., Pic S., Chatti K. Protective device during Airway Management in Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Anesthesiology. 2020;06:06. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asokan K., Babu B., Jayadevan A. Barrier enclosure for airway management in COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Anaesthesia. 2020;64(14 Supplement 2):S153–S154. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_413_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cartwright J., Boyer T.J., Hamilton M.C., Ahmed R.A., Mitchell S.A. Rapid prototype feasibility testing with simulation: improvements and updates to the Taiwanese “aerosol box”. J Clin Anesth. 2020;66:109950. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim M., Khan E., Babazade R., Simon M., Vadhera R. Comparison of the effectiveness of different barrier enclosure techniques in protection of healthcare workers during tracheal intubation and Extubation. A&A Practice. 2020;14(8) doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore R.K., Saldana C., Wright D.W., Klein A.M. Intubation Containment System for Improved Protection from Aerosolized Particles during Airway Management. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2020;8 doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2020.2993531. no pagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perella P., Tabarra M., Hataysal E., Pournasr A., Renfrew I. Minimising exposure to droplet and aerosolised pathogens: a computational fluid dynamics study. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.30.20117671. 2020.05.30.20117671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brar S., Daya J., Schuster-Bruce J., Krishna S., Daya H. St George’s COVID shield for use by ENT surgeons performing tracheostomies. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.04.20087072v1. (preprint) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson J.P., Wong D.N., Verco L., Carter R., Dzidowski M., Chan P.Y. Measurement of airborne particle exposure during simulated tracheal intubation using various proposed aerosol containment devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia (Lond) 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cubillos J., Querney J., Rankin A., Moore J., Armstrong K. A multipurpose portable negative air flow isolation chamber for aerosol-generating procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Anaesthesia. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martel M.L., Reardon R.F. Aerosol Barrier Hood for Use in the Management of Critically Ill Adults With COVID-19. Ann. Emergency Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwasaki N., Sekino M., Egawa T., Yamashita K., Hara T. Use of a plastic barrier curtain to minimize droplet transmission during tracheal extubation in patients with COVID-19. Acute Med. 2020;7(1) doi: 10.1002/ams2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta H.J., Patterson M., Gravenstein N. Barrier enclosure using a Mayo stand and plastic sheet during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients and its effect on reducing visible aerosol dispersion on healthcare workers. J Crit Care. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babu B, Shivakumar S, Dr Asokan K. "Thinking outside the box in COVID-19 era"-Application of Modified Aerosol Box in Dermatology. Dermatologic Therapy. 2020:e13769. 10.1111/dth.13769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Adir Y., Segol O., Kompaniets D., Ziso H., Yaffe Y., Bergman I., et al. COVID-19: minimising risk to healthcare workers during aerosol-producing respiratory therapy using an innovative constant flow canopy. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):05. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01017-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosseini Boroujeni SM, Khajehaminian MR, Hekayati M. Developing a Simply Fabricated Barrier for Aerosol Generating Procedures. J. Disaster Emergency Res.. 2020:0-.

- 32.Bassin B., Haas N., Puls H., Kota S., Kota S., Ward K. 2020. Rapid development of a portable negative pressure procedural tent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill E, Crockett C, Circh RW, Lansville F, Stahel PF. Introducing the "corona Curtain": An innovative technique to prevent airborne COVID-19 exposure during emergent intubations. Patient Safety Surgery. 2020;14(1) 10.1186/s13037-020-00247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Quadros CA, Leal MCBDM, Baptista-Sobrinho CA, Nonaka CKV, Souza BSF, Milan-Mattos JC, et al. Environmental safety evaluation of the protection and isolation system for patients with covid-19. medRxiv. 2020:2020.06.04.20122838. 10.1101/2020.06.04.20122838. [DOI]

- 35.Yang Y.L., Huang C.H., Luk H.N., Tsai P.B. Adaptation to the Plastic Barrier Sheet to Facilitate Intubation during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesthesia analgesia. 2020;27 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown S., Patrao F., Verma S., Lean A., Flack S., Polaner D. Barrier system for airway management of COVID-19 patients. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):e34–e35. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asenjo J.F. Safer intubation and extubation of patients with COVID-19. Can J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01666-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan Z., Khoo Deborah Wen S., Zeng L.A., Tien Jong-Chie C., LAK Yang, Ong Y.Y., et al. Protecting health care workers in the front line: Innovation in COVID-19 pandemic. J. Global Health. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayyan S.M., Raju K.N.P., Jain N., Vivekanandan M. Cost-effective innovative personal protective equipment for the management of COVID-19 patients. J Glob Infect. 2020;12(2):113. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_93_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayin I., Devecioglu I., Yazici Z.M. A Closed Chamber ENT Examination Unit for Aerosol-Generating Endoscopic Examinations of COVID-19 Patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0145561320931216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell C. Development of a Device to Reduce Oropharyngeal Aerosol Transmission. J. Endodontics. 2020;07 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuchida T., Fujitani S., Yamasaki Y., Kunishima H., Matsuda T. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2020. Development of a protective device for RT-PCR testing of COVID-19; pp. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki S., Kusano C., Ikehara H. Simple barrier device to minimize facial exposure of endoscopists during COVID-19 pandemic. Digestive Endoscopy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/den.13717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kinjo S., Dudley M., Sakai N. Modified Wake Forest Type Protective Shield for an Asymptomatic, COVID-19 Non-Confirmed Patient for Intubation Undergoing Urgent Surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2020;08 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anon J.B., Denne C., Rees D. Patient-Worn Enhanced Protection Face Shield for Flexible Endoscopy. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820934777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straube F., Wendtner C., Hoffmann E., Volz S., Dorwarth U., Engel M., et al. Universal mobile protection system for aerosol-generating medical interventions in COVID-19 patients. Critical Care. 2020;24(1) doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02969-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Filho WA, Teles TSPG, da Fonseca MRS, Filho FJFP, Pereira GM, Pontes ABM, et al. Barrier device prototype for open tracheotomy during COVID-19 pandemic. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020, 10.1016/j.anl.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Cordier P.Y., De La Villeon B., Martin E., Goudard Y., Haen P. Health workers’ safety during tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients: Homemade protective screen. Head Neck. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hed.26222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow V.L.Y., Chan J.Y.W., Ho V.W.Y., Pang S.S.Y., Lee G.C.C., Wong M.M.K., et al. Tracheostomy during COVID-19 pandemic—Novel approach. Head Neck. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hed.26234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertroche J.T., Pipkorn P., Zolkind P., Buchman C.A., Zevallos J.P. Negative-Pressure Aerosol Cover for COVID-19 Tracheostomy. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surgery. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prabhakaran K., Malcom R., Choi J., Chudner A., Moscatello A., Panzica P., et al. Open Tracheostomy for Covid19 Positive Patients: A Method to Minimize Aerosolization and Reduce Risk of Exposure. J. Trauma Acute Care Surgery. 2020;11 doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw K.M., Lang A.L., Lozano R., Szabo M., Smith S., Wang J. Intensive care unit isolation hood decreases risk of aerosolization during noninvasive ventilation with COVID-19. Canadian J. Anesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01721-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fox T.H., Silverblatt M., Lacour A., de Boisblanc B.P. Negative Pressure Tent to Reduce Exposure of Health Care Workers to SARS CoV-2 During Aerosol Generating Respiratory Therapies. Chest. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pollaers K., Herbert H., Vijayasekaran S. Pediatric Microlaryngoscopy and Bronchoscopy in the COVID-19 Era. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Francom C.R., Javia L.R., Wolter N.E., Lee G.S., Wine T., Morrissey T., et al. Pediatric laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A four-center collaborative protocol to improve safety with perioperative management strategies and creation of a surgical tent with disposable drapes. Int. J. Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110059. no pagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsai P.B. Barrier Shields: Not Just for Intubations in Today’s COVID-19 World? Anesth Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lang A.L., Shaw K.M., Lozano R., Wang J. Effectiveness of a negative-pressure patient isolation hood shown using particle count. Br. J. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hellman S., Chen G.H., Irie T. Rapid clearing of aerosol in an intubation box by vacuum filtration. Br. J. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Convissar D., Chang C.Y., Choi W.E., Chang M.G., Bittner E.A. The vacuum assisted negative pressure isolation Hood (VANISH) system: novel application of the Stryker Neptune TM suction machine to create COVID-19 negative pressure isolation environments. Cureus. 2020;12(5) doi: 10.7759/cureus.8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolter N.E., Matava C.T., Papsin B.C., Oloya A., Mercier M.E., Salonga E., et al. Enhanced draping for airway procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(2):304–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campos S., Carreira C., Marques P.P., Vieira A. Endoprotector: protective box for safe endoscopy use during COVID-19 outbreak. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(6):E817–E821. doi: 10.1055/a-1180-8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luis S., Margarita H., Javier P., Daniela S. New protection barrier for endoscopic procedures in the era of pandemic COVID-19. VideoGIE. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kobara H., Nishiyama N., Masaki T. Shielding for patients using a single-use vinyl-box under continuous aerosol suction to minimize SARS-CoV-2 transmission during emergency endoscopy. Digestive Endoscopy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/den.13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goenka M., Afzalpurkar S., Jajodia S., Shah B.B., Tiwary I., Sengupta S. 2020. Cover Page Dual Purpose Easily Assembled Aerosol Chamber Designed for Safe Endoscopy and Intubation during COVID Pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carron J.D., Buck L.S., Harbarger C.F., Eby T.L. A Simple Technique for Droplet Control During Mastoid Surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chari D.A., Workman A.D., Chen J.X., Jung D.H., Abdul-Aziz D., Kozin E.D., et al. Aerosol dispersion during Mastoidectomy and custom mitigation strategies for Otologic surgery in the COVID-19 era. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820941835. 194599820941835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen C., Shen N., Li X., Zhang Q., Hei Z. New device and technique to protect intubation operators against COVID-19. Intensive Care Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharma S.S., Singh D.K., Yadav A.K., Swain J., Kumar S., Jain D.K., et al. Disposable customized aerosol containment chamber for oral cancer biopsy: A novel technique during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jso.25962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maharaj S.H. The nasal tent: an adjuvant for performing endoscopic endonasal surgery in the Covid era and beyond. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.David A.P., Jiam N.T., Reither J.M., Gurrola J.G., 2nd, Aghi M.K., El-Sayed I.H. Endoscopic skull base and transoral surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: minimizing droplet spread with negative-pressure otolaryngology viral isolation drape. Head Neck. 2020;01:01. doi: 10.1002/hed.26239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gordon S.A., Deep N.L., Jethanamest D. Exoscope and personal protective equipment use for Otologic surgery in the era of COVID-19. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):179–181. doi: 10.1177/0194599820928975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wexner S.D., Cortes-Guiral D., Gilshtein H., Kent I., Reymond M.A. COVID-19: impact on colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(6):635–640. doi: 10.1111/codi.15112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Anguita R., Tossounis H., Mehat M., Eames I., Wickham L. Surgeon’s protection during ophthalmic surgery in the Covid-19 era: a novel fitted drape for ophthalmic operating microscopes. Eye (Lond) 2020;34(7):1180–1182. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0931-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hasmi A.H., Khoo L.S., Koo Z.P., Suriani M.U.A., Hamdan A.N., Yaro S.W.M., et al. The craniotomy box: an innovative method of containing hazardous aerosols generated during skull saw use in autopsy on a COVID-19 body. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020;04 doi: 10.1007/s12024-020-00270-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gonzalez-Ciccarelli L.F., Nilson J., Oreadi D., Fakitsas D., Sekhar P., Quraishi S.A. Reducing transmission of COVID-19 using a continuous negative pressure operative field barrier during oral maxillofacial surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Cases. 2020;6(3):100160. doi: 10.1016/j.omsc.2020.100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Babu B., Gupta S., Sahni V. Aerosol box for dentistry. Br Dent J. 2020;228(9):660. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kulkarni R.R., Stephen M., Shashank A., Mandhal L.N. Novel method of performing brachial plexus block using an aerosol box during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Anesthesia. 2020;66 doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109943. no pagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Endersby R.V.W., Ho E.C.Y., Spencer A.O., Goldstein D.H., Schubert E. Barrier Devices for Reducing Aerosol and Droplet Transmission in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Alternative Solutions. Anesth Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jazuli F., Bilic M., Hanel E., Ha M., Hassall K., Trotter B.G. Endotracheal intubation with barrier protection. EMJ. 2020;01 doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chahal A.M., Van Dewark K., Gooch R., Fukushima E., Hudson Z.M. A Rapidly Deployable Negative Pressure Enclosure for Aerosol-Generating Medical Procedures. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.14.20063958. 2020.04.14.20063958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen J.X., Workman A.D., Chari D.A., Jung D.H., Kozin E., Lee D.J., et al. Demonstration and mitigation of aerosol and particle dispersion during mastoidectomy relevant to the COVID-19 era. Otol. Neurotol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Giampalmo M., Pasquesi R., Solinas E. Easy and Accessible Protection against Aerosol Contagion during Airway Management. Anesthesiology. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lyaker M.R., Al-Qudsi O.H., Kopanczyk R. Looking beyond tracheal intubation: addition of negative airflow to a physical barrier prevents the spread of airborne particles. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hirose K., Uchida K., Umezu S. Airtight, flexible, disposable barrier for extubation. J. Anesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02804-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dalli J., Khan M.F., Marsh B., Nolan K., Cahill R.A. Evaluating intubation boxes for airway management. Br. J. Anaesthesia. 2020;14 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gould C.L., Alexander P.D.G., Allen C.N., McGrath B.A., Shelton C.L. Protecting staff and patients during airway management in the COVID-19 pandemic: are intubation boxes safe? Br. J. Anaesthesia. 2020;13 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brown H., Preston D., Bhoja R. Thinking outside the Box: A Low-cost and Pragmatic Alternative to Aerosol Boxes for Endotracheal Intubation of COVID-19 Patients. Anesthesiology. 2020;29 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clariot S., Dumain G., Gauci E., Langeron O., Levesque É. Minimising COVID-19 exposure during tracheal intubation by using a transparent plastic box: a randomised prospective simulation study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamal P.K., Chaurasia R.B., Pokhrel N., Pandey D., Shrestha G.S. An affordable videolaryngoscope for use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(7):e893–e894. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30259-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Serdinsek M., Stopar Pintaric T., Poredos P., Selic Serdinsek M., Umek N. Evaluation of a foldable barrier enclosure for intubation and extubation procedures adaptable for patients with COVID-19: a mannequin study. J Clin Anesth. 2020;67:109979. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seger C.D., Wang L., Dong X., Tebon P., Kwon S., Liew E.C., et al. A Novel Negative Pressure Isolation Device for Aerosol Transmissible COVID-19. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000005052. Publish Ahead of Printhttps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bai JW, Ravi A, Notario L, Choi M. Opening the discussion on a closed intubation box. Trends Anaesthesia Crit. Care. 2020, 10.1016/j.tacc.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Pelley L. How a simple plastic box could protect health-care workers across Canada from COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/how-a-simple-plastic-box-could-protect-health-care-workers-across-canada-from-covid-19-1.5525262; accessed September 7 2020.

- 94.Duggan L.V., Marshall S.D., Scott J., Brindley P.G., Grocott H.P. The MacGyver bias and attraction of homemade devices in healthcare. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66(7):757–761. doi: 10.1007/s12630-019-01361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]