Abstract

Introduction

In recent months, some attempts were made to understand the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health. Despite recent research that suggests COVID-19 and lockdown measures may eventually impact sexual response and sexually related behaviors, we are missing clinical sexologists’ perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 in sexual health. Such perspectives could inform a preliminary framework aimed at guiding future research and clinical approaches in the context of COVID-19.

Aim

To explore the perspectives of clinical sexologists about the impact of COVID-19 on their patients’ sexual health, as well as the professional challenges they have faced during the current pandemic. Findings are expected to inform a preliminary framework aimed at understanding the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health.

Methods

We conducted an online qualitative exploratory survey with 4 open-ended questions with 39 clinical sexologists aged between 32 and 73 years old. The survey was advertised among professional associations’ newsletters. We performed a Thematic Analysis using an inductive, semantic, and (critical) realist approach, leading to a final thematic map.

Main Outcome Measures

The outcome is the thematic map and the corresponding table that aggregates the main themes, subthemes, and codes derived from participants’ answers and that can serve as a preliminary framework to understand the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health.

Results

The final thematic map, expected to serve as a preliminary framework on the impact of COVID-19 in sexual health, revealed 3 main themes: Clinical Focus, Remapping Relationships, and Reframing Technology Use. These themes aggregate important interrelated issues, such as worsening of sexual problems and dysfunctions, mental health, relationship management, the rise of conservatism, and the use of new technology that influences sexuality and sexual health-related services.

Conclusion

The current study allowed us to develop a preliminary framework to understand the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health. This framework highlights the role of mental health, as well as the contextual nature of sexual problems, and subsequently, their relational nature. Also, it demonstrates that the current pandemic has brought into light the debate of e-Health delivery within clinical sexology.

Pascoal PM, Carvalho J, Raposo CF, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Sexual Health: A Preliminary Framework Based on a Qualitative Study With Clinical Sexologist. Sex Med 2021;9:100299.

Key Words: Sexual Health, Sexual Dysfunctions, Sexual Behavior, COVID-19, Mental Health

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 rapidly escalated to the status of a pandemic, raising serious concerns about citizens’ health. In a few weeks, COVID-19 had a significant impact on worldwide economies, social, cultural and organizational entities, as well as on individuals’ mental and physical health, reaching the level of crisis as defined by the World Health Organization, that is, an insidious process that cannot be defined in time.1 The several lockdowns adopted by most countries were shown to have detrimental effects, including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, or anger; some of these are long-lasting effects,2 which demonstrates the negative impact of COVID-19 on mental health.3, 4, 5, 6 Additionally, women, young people, and people who lost their jobs, reported the most severe psychological symptoms.7 Women are believed to be particularly at risk during crisis situations,8 which now include the COVID-19 pandemic. Such discrepancy suggests the need for a gendered approach to studying and intervening in sexual health in the context of COVID-19.

Within the sphere of human sexuality, recent attempts have been made in order to establish the impact of COVID-19 and physical isolation measures on sexual health.9 Indeed, such measures are expected to negatively impact sexual and interpersonal relationships or even prompt intimate partner (sexual) violence and risky sexual behaviors, as all of these areas are strongly rooted in individuals’ emotional adjustment.10 In line with these assumptions, initial data from Han Chinese citizens revealed that 25% of respondents reported a decrease in sexual desire, 44% reported a reduction in sexual partners, and 37% reported to have decreased sexual frequency.11 Furthermore, 32% of men and 39% of women reported decreased sexual satisfaction, and most participants with a history of risky sex actually decreased risky behavior.11 Another study on the sexual outlets during COVID-19 self/social isolation showed that citizens living in the UK reported engaging in sexual activity at least once a week; most interesting, alcohol consumption and the number of days under self/social isolation were positively related with having sexual activity.12 As for female sexuality, findings from a Turkey sample revealed that women reported increased frequency of sexual intercourse during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as decreased desire to become pregnant, decreased use of contraception, and more menstrual complaints. Indeed, despite better scores on the FSFI before the pandemic, women reported increased sexual desire and frequency of sexual intercourse during COVID-19.13 These findings are actually consistent with previous data showing that a proportion of individuals increase sexual desire and diverse sexual outlets (eg, masturbation, attention toward erotic cues, cybersex) under emotionally negative events (cf.,14, 15, 16). Likewise, an Italian online survey showed that confinement measures were associated with a high prevalence of pornography use and increased autoerotism, as well as increased sexual desire without change17 of the frequency of sexual intercourse, and a significant decrease in sexual satisfaction.13 In sum, COVID-19 crisis may prompt or decrease different aspects of sexual life, depending on explored variables and diverse determinants, such as gender, privacy, age, or the perception of confinement as unbearable.18,19

Another important area within the sphere of human sexuality is human sexual rights. Chief entities such as the World Association for Sexual Health have defined a series of resolutions aimed at ensuring human sexual rights during COVID-19.20 Gender gap and gender violence toward women and sexual minorities are expected to be maximized by the current state of the pandemic.10 The detrimental effects on women’s sexual and reproductive health are particularly worrisome.8 An intersectional approach to COVID-19’s impact reveals disparities in power, exposing decades of health and social inequalities, and revealing that those who belong to poorer and conflict zones may be unable to protect themselves from the virus, and their access to sexual and reproductive health may be unwarranted.21 The clinical approach in the context of sexual health needs to take intersection into account and acknowledge that different identities (eg, sexual minorities) may experience different forms of social injustice, namely unbalanced access to sexual health services or lack of attention to sexual rights.22,23 Indeed, the reorganization of health services to assist COVID-19 may negatively impact the availability of sexual and reproductive health services, including access to safe interruption of unplanned pregnancies, especially in sexual diverse populations.24 Sexual health professionals are better positioned than other professionals to make sure sexual rights are respected during pandemic times “as health-care providers are often not encouraged or sufficiently trained to feel comfortable providing services, which place pleasure or rights at the center of their engagement with clients”.23

Despite the research on the topic of COVID-19 and human sexuality being still germinal, current findings are indicative of changes in sexual response and behavior. Indeed, the current pandemic has opened an unprecedented line of research aimed at exploring human sexuality. Yet, at the present moment, we have no knowledge of studies steaming from clinical contexts, particularly from the views of clinical sexologists. According to Paul and colleagues (2020), professionals’ awareness about this topic is particularly important to guarantee their proper counseling and to deal with the limitations of traditional support and recommendations during outbreaks. Research steaming from professionals’ views may actually increase our understanding of the meaning of sexual health changes during the lockdown, thus offering a more comprehensive approach to current COVID-19 and sex research data. Accordingly, this study is aimed at exploring clinical sexologists’ perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on their patient’s sexual health.

In order to accomplish this goal, we developed an online qualitative exploratory survey with 4 open questions, directed to certified Portuguese clinical sexologists. Our work was developed in line with principles that guide qualitative research and advocate that researchers need to present an open-ended research question and not an hypothesis.25 Ultimately, we aimed at answering the research question “How do certified clinical sexologists perceive the impact of COVID-19 in patients’ sexual health and in their clinical practice?” in order to develop a thematic map that could serve as a preliminary framework to study the impact of COVID-19 in sexual health.

Methods

Participants

The current sample included 39 participants; among these, 24 (66.66%) were women. The mean age of the total sample was 48.59 years (SD = 10.11, range 32 to 73), and the mean time of practicing clinical sexology was 16 years (SD = 10.53, range 2 to 40). 15 participants (38.5%) were medical doctors (7 psychiatrists, 3 urologists, 3 gynecologists; 2 did not specify), 22 were clinical psychologists (56.5%), and 1 was a nurse (3%). Regarding the clinical settings where they usually practice clinical sexology, 5 (12.8%) work only in public settings, 14 (35.9%) work only in private settings, and 20 (51.3%) work in public, as well as private settings.

Procedure

The current study was developed and implemented during the lockdown period in Portugal, which took place from March 22nd to June 1st (with a transitioning phase on May 4th and May 18th).

A participatory research approach26 was followed. Accordingly, the study was set up with the involvement and support of the Members of the Board of Directors of the Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology (BD-SPSC). After exploring the BD-SPSC interest in the project, the initial research question was presented to the Board of Directors (BD), and the versions of the survey were revised for relevancy and adequacy to the target population (certified practicing clinicians) until a final version of the manuscript was agreed upon. Based on the knowledge of some of the members of the BD-SPSC about previous studies developed with Portuguese clinical sexologists,27 which had reduced compliance to interviews and the difficulty to find a common agenda to develop interviews, it was agreed that an online anonymous survey would be the best option to guarantee a timely response of active clinicians, as well as the feasibility of the study. We followed the ethical and deontological guidelines and principles presented in the Helsinki Declaration,28 as well as those presented in the European Textbook on Ethics in Research.29 The study was reviewed for objectives, methods, and ethics by the Portuguese Association of Psychologists. In order to guarantee anonymity, we asked for a minimum socio-demographic data. To be included in the present study, participants had to (a) speak Portuguese, (b) have an education (certified degree) and supervised training in clinical sexology (including sex therapy and sexual medicine), and (c) being an active practitioner of clinical sexology since before the pandemic was declared (this criterion was settled mandatory in the informed consent). The certification was defined as having a Post-Graduation course (usually more than 80 hours), or to be an EFS and ESSM Certified Psycho-Sexologist, or to have a clinical sexology/sex therapist degree by the Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology (SPSC).

An online survey, containing the items of interest (see next paragraph), was disseminated through newsletters, reaching national Clinical Sexologists; these were members of 3 major professional societies in Portugal: Portuguese Society of Clinical Sexology, Portuguese Association of Psychologists, and Portuguese Association of Family Planning. Potential. The advertising of the study clearly stated that the study was aimed at clinicians with both an established degree and training in clinical sexology, sex therapy, or sexual medicine and who were active practitioners in this field when the pandemic started. Eligible participants were directed to a webpage containing informed consent, as well as information concerning inclusion criteria and aims of the study. This is a convenience sample.

In the current study, the following open questions were analyzed: (1) “What were the most common problems presented by patients in your clinical practice as a clinical sexologist before the pandemic?” (2) “What are the most common problems that patients are presenting during the lockdown in your practice as a clinical sexologist?” (3) “What personal difficulties have you found in the practice of clinical sexology since the beginning of the lockdown?” and (4) “Do you consider lockdown and social distancing measures will have an impact in people’s sexuality? If so, can you explain in what way?”

Data Analysis

SPSS 26 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the purposes of descriptive statistics. Qualitative material was handled and analyzed using the QSR NVivo Pro 11 software for Windows.

We followed Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis procedures (2012)30 for the purposes of qualitative data analysis. Thematic analysis is a non-quantitative approach to data, so it does not advocate for the existence of quantitative indicators of agreement among raters, nor aims for replication, neither for testing differences between groups. These procedures focus on capturing, recording, and organizing aspects of people’s lives in an interpretative framework, allowing for interpretation, that is, “qualitative research is about meaning, not numbers.”31 (p.20). It is a flexible method that allows researchers to identify, analyze, and describe how codes and patterns of meaning combine into broader themes. In the current study, we follow an inductive, semantic, and (critical) realist approach to thematic analysis; that is, we depart from the explicit content of the data to inform the development of themes. Each data item (ie, each answer) may have multiple codes, depending on the amount of material provided; that is, attribution of a code to an answer does not exclude the possibility of adding other meaningful codes to the same answer. After familiarization and coding of all the data sets (ie, all answers), authors are involved in the revision of the coding, which further leads to an interpretative process. The continuous recursive process of codification, interpretation, and recodification of data leads to a final thematic map. In the current study, to ensure/increment the validity of the research, the third and fourth authors individually coded the raw data into subthemes and themes. The 2 distinct final thematic maps were checked by the first author until a consensus and agreement were reached.32 Finally, the 2nd author autonomously verified if the final thematic map accommodated the raw material provide by the participants’ answers, giving input into naming the themes and subthemes.

Results

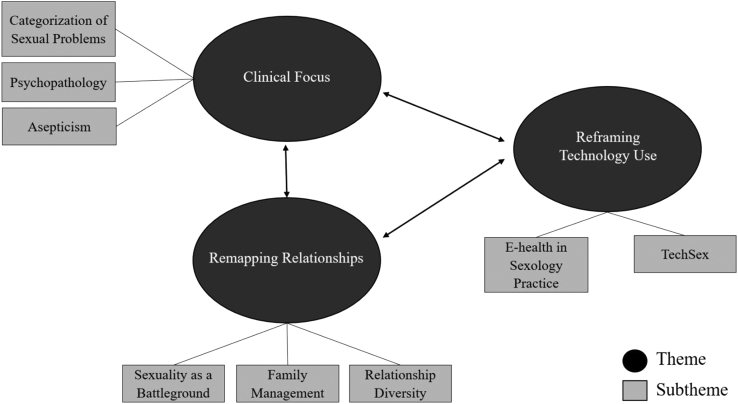

Participants’ answers were globally rich, allowing for multiple coding and theme development. The preliminary framework to understand the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health is represented by the comprehensive final thematic map (Figure 1) concerning the main research question “How do certified clinical sexologists perceive the impact of COVID-19 in patients’ sexual health and in their clinical practice?” portrays 3 main themes: Clinical Focus, Remapping Relationships, and Reframing Technology Use.

Figure 1.

A preliminary framework to understand the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health.

These themes were interrelated, as answers from one participant informed more than one theme. The main themes and subthemes are described in the following paragraphs (see Table 1 for a complete representation of how codes and subthemes were integrated into the main themes).

Table 1.

Final map Proposal

| Themes | Subthemes | Codes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clinical Focus | 1.1. Categorization of Sexual Problems | 1.1.1. Desire | “Change in desire levels, accentuating desire discrepancy and difficulty in maintaining an active sex life” “The anxiety generated by the situation can lead to a decrease in sexual interest.” “Differences in sexual desire levels and dissatisfaction with frequency of sexual encounter as men and women deal with marital conflict in different ways and the lockdown is related to more conflict” |

| 1.1.2. Erectile Dysfunction | “(…) erectile dysfunction” “erectile problems, eventually without criteria for dysfunction. (…) |

||

| 1.1.3. Premature ejaculation | “Premature ejaculation” “Some men who have been inactive will be more anxious, more rapid ejaculations (…) |

||

| 1.1.4. Orgasm | “I have had more complaints from women associated with the difficulties in reaching orgasm” | ||

| 1.1.5. Transhealth | “More discomfort gender identity issues (diversity and emotional difficulties)” “information about a transgender child.” “concerns about access to trans health care” |

||

| 1.2. Psychopathology | 1.2.1. Sexual compulsion | “Addiction/pornography addiction”; "Forensic sexology (…) hypersexuality/sexual addiction” | |

| 1.2.2. Emotional distress | “sadness. uncertainty about the future.” “I think the isolation of people who really want a relationship can lead them to emotional difficulties like depression or anxiety” |

||

| 1.3. Asepticism | 1.3.1. Hygienism | “Hygienist view of sexuality” “People will be more cautious with casual relationships, with the transition to the act in relationships via app” |

|

| 1.3.2. Fear of contamination | “(…) Some fears associated with the disease itself and the fear of contamination (especially when one of the couple continues to work outside the home) (…)” “It will have some impact at the beginning (due to fear of contagion (…))” |

||

| 2. Remapping Relationships | 2.1. Sexuality as a battleground | 2.1.1. Sexuality as a symptom | “(…) More questioning about the validity of the relationship, using sexuality issues as a reason (…)” “Desire problems associated with increased marital conflicts; sex appears a lot as an expression of marital conflicts” “dissatisfaction with sexuality within the relationship is more obvious” “Lack of satisfaction with sexuality that reflects preexisting problems problems” |

| 2.1.2. Solitude | “Sexual loneliness, use of apps for sex and tension in developing relationships in this way” “(…) Lack of partners, feelings of loneliness, lack of attractiveness and experiencing disconnection from people” |

||

| 2.2. Family Management | 2.2.1. Conjugal conflicts | “More marital conflict, lack of pleasure in the relationship” “Conflicts between couples and family management” “More discussions about relationships with extended family, namely the elderly” |

|

| 2.2.2. Parenting | “Couples talk more about parenting in the context of sexology, conflicts that arise from parenting” “Family management (children, homeschool, telework)” |

||

| 2.3. Relationship Diversity | 2.3.1. Non-Monogamies | “I also believe it will affect casual encounters and people who did not maintain stable monogamous relationships” “I imagine that some people who have extra-marital relationships want to make them more ethical and recognized, to justify visits, even during quarantines or future isolations, and as such, to approach polyamorous relationships.” |

|

| 2.3.2. Conservatism | “Emphasis on monogamy and commitment relationships as more protective.” “(…) perhaps a return to the idea of the traditional family and monogamy, as happened with AIDS” |

||

| 3. Reframing Technology Use | 3.1. E-health in Sexology Practice | 3.1.1. Non verbal comunication | “The clarification and consultation online is somewhat limiting. I like the visual context and I need to properly evaluate facial expression.” “The online approach also has some disadvantages (eg, loss of important non-verbal forms of communication for the therapeutic process)” |

| 3.1.2. Therapeutic relationship | “Clients prefer intervention in an office, some have postponed interventions for when face-to-face intervention is possible (…)” “Provide an empathetic and close consultation via internet; difficulties in managing remote therapy” |

||

| 3.1.3. Referral network | “(...) complaints for which I have no training, I have to refer and many psychology and therapy colleagues are not so available” “Less referral sources (…)” |

||

| 3.1.4. Technical resources | “I have a hard time accompanying couples, because the screen is too small to include the 2 members of the couple and even if asking regularly, there is a part of the interaction outside” “Network that fails, interruptions in sound or image, (...) does not always have fixed devices (screen that shakes, falls, etc.) ” |

||

| 3.1.5. Digital security | “Difficulties in guaranteeing 100% confidentiality, since the programs are susceptible to suffer piracy” “Secure platforms” |

||

| 3.2. TechSex | 3.2.1. Sexual Explicit Material (coping strategy) | “(…) Pornography Consumption as a form of coping” “(…) single women will become more addicted to pornography…” |

|

| 3.2.2. Technology for Sexual Expression | “It will be a sexuality more focused on online without physical contact” “Technology can also be more present in the experience of sexuality” “Spicing up distant relationships with sexting, using online sexual activity for arousal purposes, search for sex using different apps and platforms” |

Clinical Focus

The main theme Clinical Focus aggregates answers that deal with clinical aspects, with a special focus on sexual diagnosis and related complains, deemed as the focus of intervention (eg, subtheme Categorization of Sexual Problems). Clinical Focus further aggregates wording mirroring the detrimental effects of mental health problems in sexual functioning and sexuality as a whole. (eg, subtheme Psychopathology). Additionally, it translates emerging topics, forecasted as prominent, given COVID-19 lockdown experience (eg, subtheme Asepticism).

Remapping Relationships

The main theme Remapping Relationships integrates answers stressing the role of sexuality within the context of amorous dynamics. It includes sexuality as a source of conflict, but also the experience of solitude due to the absence and difficulty finding partners during pandemic (eg, subtheme Sexuality as a Battleground). It also includes subthemes targeting the burden of family roles, such as parenting. These roles are believed to pressure couples and relationship dynamics because they jeopardy the erotic atmosphere and chance of erotic involvement (eg, subtheme Family Management). Furthermore, findings pop out a subtheme favoring non-monogamous relationships as a result of couple’s decisions to open to new relational structures or to live ethical non-monogamous relationships, as well as a subtheme on increased difficulties managing polyamory in the context of COVID-19. Paradoxically, Remapping Relationships further includes the trend to focus on traditional and conservative relationships as a means to keep safe from infection (eg, subtheme Relationship Diversity).

Reframing Technology Use

Finally, a third theme named Reframing Technology Use translates the important role that new technologies have acquired in the context of clinical sexology, either as a means to support and develop clinical interventions (eg, subtheme E-health in Sexology Practice) or as means to cope with sexual urges and/or express one’s sexuality through the use of apps or sexually explicit material (eg, subtheme Tech Sex).

Although we explored this possibility, we found no linkage of the results to the different contexts of practice (private setting, public setting, both settings).

Discussion

The current study was aimed at evaluating clinical sexologists’ perceptions regarding the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health, as well as clinicians’ appraisal of the main professional challenges faced during the current pandemic with the purpose of developing a preliminary framework on the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health.

As previously expected, clinicians’ perceptions supported the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health. Furthermore, individual, interpersonal, as well as societal factors, were perceived as playing an important role, shaping mental health and relationship dynamics, and further posing new challenges to clinical practice.

Findings on Thematic Analysis revealed 3 major interconnected themes: Clinical Focus, Remapping Relationships, and Reframing Technology Use.

Clinical Focus regards the appraisal of sexual difficulties as perceived during the current pandemic. Sexual dysfunction and difficulties have been expected to be triggered by the context of COVID-19, as previously discussed.10 In line with those assumptions, clinicians identified a series of sexual difficulties aggravated by the current pandemic (cf, Subtheme Categorization of Sexual Problems). Furthermore, mental health issues, as triggered by COVID-19, were seen as precursors of sexual difficulties, thus believed to have an indirect effect on sexual problems (cf. Subtheme Psychopathology). Likewise, clinicians considered that fear of contamination and restrictive measures to prevent infection might contribute to sexual difficulties as well (Asepticism). These findings partially align with current evidence, as the impairment of sexual functioning during COVID-19 has yet to be clearly established. Recent studies support the decreased frequency of sexual activities,11 but also increased sexual desire and frequency of sexual outlets,12 followed by lowered sexual satisfaction.13 However, it is worth noting that findings derived from different methodological approaches and data on men and women’s sexual dysfunction during COVID-19 are still germinal. Given that the current study focused on clinicians’ perceptions rather than community surveys, it is comprehensible that the Clinical Focus theme mirrors diagnostic entities (eg, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation) besides dimensional outcomes on sexual difficulties or outlets. In addition, professionals considered sexual minorities, particularly transsexuals’ health care, to be a focus of concern. Indeed, it has been recognized that COVID-19 has worsened transsexuals’ social, family, or clinical adjustment.25,26

Sexual compulsivity issues and risky behavior have further emerged in the Clinical Focus theme. Indeed, given social isolation, individuals are expected to consume more pornography or increase sexual outlets as means to cope with dysfunctional mood states.10 Clinicians’ perspectives on the effects of COVID-19 in sexual health are in line with current assumptions supporting that sexual compulsivity-like conditions may be aggravated by increased consumption of pornography and dating apps during the context of social isolation.33,34 Additionally, clinicians’ appraisals of the overlapping between mental health issues and sexual problems stress the need to consider sexual complaints as part of the large spectrum of psychopathology conditions. Sexual complaints may be signaling preexisting psychopathological states worsen by COVID-19. Likewise, preexisting inflexible beliefs and thinking styles regarding sexuality35,36 were appraised as vulnerability factors for sexual dysfunction and may be triggered during social isolation periods due to increased opportunities for sexual interaction within amorous people in cohabitation. To sum up, the context of COVID-19 is regarded as a predisposing factor for sexual dysfunction and difficulties, either by influencing new living and couples’ dynamics or by aggravating individuals’ mental condition and trigger maladaptive thinking styles concerning sexual aspects. The overlapping between psychopathology phenomena and sexual dysfunction37,38 is most stressed during COVID-19.

Still, within the Clinical Focus theme, clinicians’ considered that the current pandemic may constitute a predisposing factor for sexual difficulties, by prompting intrusive thoughts and fear of contamination during intimate and sexual relationships (cf. subtheme Asepticism). Contamination worries were brought to light and socially spread in the early appearance of HIV.39 The current context of a pandemic may eventually replicate previous associations between the expression of sexuality and the sense of disease, favoring negative visions regarding sex and sexual diversity. Indeed, past stigmatization of minorities negatively impacted the control of HIV,39 and the current pandemic may prompt similar social movements and negative health assistance outcomes.

Besides sexual dysfunction and psychopathology issues, clinicians further stressed that current pandemic had influenced patients’ relationships (theme Remapping Relationships). Findings suggest that social distancing measures triggered both individual (code Solitude) and relationship (cf., subtheme Family Management) challenges. Sexual satisfaction has been put at a challenge as well (cf., code Sexuality as a symptom), which aligns with previous evidence supporting reduced sexual satisfaction despite increased sexual activity or desire,13 during COVID-19. In addition, it is worth noting that many complaints reported under the Remapping Relationship theme do not tap into categorical recognized clinical entities, as displayed in DSM-5 or ICD-11, unlike those aggregated in the subtheme Categorization of Sexual Problems. Instead, several complaints regard sexual desire discrepancy and lack of sexual satisfaction (cf., subtheme Sexuality as a Battleground). Categorical perspectives on human sexual functioning have previously been challenged.40,41 Key sexual complaints, such as sexual desire discrepancy and sexual distress, were brought to the center of the debate, as clinical interventions should put more emphasis on them.42 Accordingly, and despite individual factors, such as mental health issues,43 relationship variables, such as communication between partners44,45 were deemed key in the current study supporting a contextual approach to sexual problems. Furthermore, clinicians perceived new family roles, resulting from COVID-19 demands, as a source of marital conflict, aggravating preexisting sexual difficulties (cf., Subtheme Sexuality as a Battleground). Such findings align with contextual views on human sexuality and sexual problems,40,41 stressing the role of marital conflict in sexual dysfunction, with a special emphasis on sexual (in)satisfaction.45 Understanding the effects of the pandemic in couples’ dynamics seems of priority. Finally, clinicians considered additional challenges for those living (non)consensual non-monogamies. Such individuals are expected to find new strategies in order to accomplish their sexual and emotional needs in a context they may feel forced to choose who to share their lockdown with. The current pandemic is believed to reinforce social appraisals on normative (sexual)relationships, favoring these because monogamous relationships are expected to provide better adjustment during social isolation. This may lead to accentuated conservatism regarding amorous relationships.

Clinicians also stated technology might have a crucial role in how individuals adjust to social isolation (Reframing Technology Use). Technology is regarded as a means to achieve sexual pleasure and safe sex. Sexting and pornography consumption may actually reveal adaptive during social isolation (subtheme Techsex).46 Technology is an important resource in the context of the pandemic, and it is shaping intimate relationships in unprecedented ways,47 and may be key to improve sexual diversity.46

Finally, clinicians considered that the current pandemic had brought e-Health to light within the specific field of sexology. Despite major professional entities such as APA48 having already claimed the benefits of e-Health, only recently the sexology domain has published guidelines49 on e-Health sexology interventions. COVID-19 has claimed e-Health as mandatory.50 Even so, it is worth noting that clinicians have stressed e-Health limitations, such as lack of awareness regarding non-verbal cues during (psycho)therapy, preference for face-to-face appointments, or poor online resources, including limited software. Indeed, despite the clear benefits of online interventions,51 many professionals struggle to adjust to the new e-Health tools.52 Besides, clinicians were still facing increased difficulties with referrals to other professionals, which may have limited treatment efficacy.

Although current literature highlights the gendered nature of the impact of crisis and pandemic states on women’s and minority rights, as well as the need to take an intersectional approach to sexual health, the current results revealed this point was not present in clinicians’ perspectives. This may be due to the fact that data was collected at an early stage of lockdown. It may further suggest that at-risk situations are not being captured by the clinical contexts we targeted in this study. Even so, such an intersectional approach should be highlighted in clinical sexology practice in order to prevent gender inequalities and promote and increase equal access to sexual health services and sexual rights.

The current study presents several limitations that must be acknowledged. The online approach captures superficial narratives rather than deep responses; the latter would be possible using interviews instead of discrete items. However, such a methodology would be less suitable in the context of confinement, possibly increasing noncompliance. In addition, the current study mirrors a sample of Portuguese sexologists’ visions; findings are obviously tied to their background training and education, as well as to the specificities of the Portuguese healthcare system. Also, the current meanings translate the clinicians’ perspectives but do not inform patients’ views. We further anticipate the current sample is not representative; there is no available nor trusted information on the total number of registered clinical sexologists in Portugal, including professionals currently working in the field. We recognize expert opinion presents a low level of scientific evidence, but, still, it can be an important basal step on the construction of scientific knowledge, especially in new fields of knowledge. Finally, data were collected during the early stages of the pandemic. Given that we are expecting severe economic consequences in the long-term, we believe findings do not capture the influence of economic adversity in individuals’ sexual health and clinicians’ practice.

The present findings mirror a sample of clinical sexologists’ perceptions of the effects of COVID-19 in sexual health. These perceptions stress the interplay between mental health issues and sexual health, namely sexual dysfunction and difficulties, as a major theme emerging during COVID-19. Similarly, couples’ dynamics as a result of pandemic adjustment were deemed at the core of sexology intervention. These visions clearly support the contextual framing of sexual problems and relationships, which should be translated into a comprehensive and systemic approach regarding sexuality phenomena. Findings further highlight the need for sexology education and training within the principles of such a comprehensive approach regarding sexual problems. Given the number of studies emerging in the context of COVID-19 and sexuality outcomes, we believe this framework can guide researchers in developing and interpreting their surveys. It can also guide clinicians on their assessment and intervention approaches, as key clinical challenges are expected to emerge. It can also guide clinicians assessing and intervening in sexual health by addressing different issues that can be of clinical interest, namely the potential brought by e-Health and the recognition of its value to intervene in mental and sexual health during the pandemic.50

Statement of authorship

Patrícia M. Pascoal: Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review & editing. Joana Carvalho: Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Catarina F. Raposo: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Joana Almeida: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Ana Filipa Beato: Writing - review & editing

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknoweldge all the colleagues who have taken the time to answer our survey.

The authors thank Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses, Associação para o Planeamento da Família, and the Board Members of Sociedade Portuguesa de Sexologia Clínica for their support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Definitions https://www.who.int/hac/about/definitions/en/

- 2.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi R., Socci V., Talevi D. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:790. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheridan Rains L., Johnson S., Barnett P. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;17:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Rey R., Garrido-Hernansaiz H., Collado S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussein J. COVID-19: what implications for sexual and reproductive health and rights globally? Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2020;28:1746065. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1746065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang K., Gaoshan J., Ahonsi B. Sexual and reproductive health (SRH): a key issue in the emergency response to the coronavirus disease (COVID- 19) outbreak. Reprod Health. 2020;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0900-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carvalho J., Pascoal P.M. Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in Portugal. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1212–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W., Li G., Xin C. Changes in sexual behaviors of young women and men during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: a convenience sample from the Epidemic area. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1225–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob L., Smith L., Butler L. COVID-19 social distancing and sexual activity in a sample of the British public. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuksel B., Ozgor F. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;150:98–102. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cyranowski J.M., Bromberger J., Youk A. Lifetime depression history and sexual function in women at midlife. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:539–548. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044738.84813.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho J., Pereira R., Barreto D. The effects of positive versus negative mood states on attentional Processes during exposure to Erotica. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:2495–2504. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0875-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Oliveira L., Carvalho J. The Link between Boredom and Hypersexuality: a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2020;17:994–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocci A., Giunti D., Tonioni C. Love at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic: preliminary results of an online survey conducted during the quarantine in Italy. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:556–557. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballester-Arnal R., Nebot-Garcia J.E., Ruiz-Palomino E. “INSIDE” project on sexual health in Spain: the impact of the lockdown Caused by COVID-19. Res Sq. 2020:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00506-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W., Li G., Xin C. Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in China. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Association for Sexual Health (WAS) 2020. Sexual Rights in the context of the global COVID-19 crisis. https://worldsexualhealth.net/sexual-rights-in-the-context-of-the-global-covid-19-crisis/. Accessed May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lokot M., Avakyan Y. Intersectionality as a lens to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for sexual and reproductive health in development and humanitarian contexts. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2020;28:1–4. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1764748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham L.F., Padilla M. Sexual rights for marginalized populations. In: Tolman D.L., Diamond L.M., Bauermeister J.A., editors. APA Handbook of sexuality and Psychology, Vol. 2: contextual approaches. APA handbooks in psychology. American Psychological Association; 2014. pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruskin S., Yadav V., Castellanos-Usigli A. Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2019;27:1593787. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Todd-Gher J., Shah P.K. Abortion in the context of COVID-19: a human rights imperative. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2020;28:1–3. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1758394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lareau A. Using the terms hypothesis and variable for qualitative work: a critical Reflection. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:671–677. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornwall A., Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1667–1676. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alarcão V., Beato A., Almeida J., Machado F.L., Giami A. Sexology in portugal: Narratives by portuguese sexologists. J Sex Res. 2015;53:1–14. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1104286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WMA, World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Commission . 2010. European Textbook on ethics in research. Publications Office of the EU. https://op.europa.eu/pt/publication-detail/-/publication/12567a07-6beb-4998-95cd-8bca103fcf43. Accessed December 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V., Clarke V., Cooper H. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H., editor. APA Handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: research Designs: quantitative, qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC US: 2012. pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V., Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for Beginners. SAGE Publications; California: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascoal P.M., Shaughnessy K., Almeida M.J. A thematic analysis of a sample of partnered lesbian, gay, and bisexual people’s concepts of sexual satisfaction. Psychol Sex. 2019;10:101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shilo G., Mor Z. COVID-19 and the changes in the sexual behavior of men who have sex with men: results of an online survey. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1827–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez T.H., Zlotorzynska M., Rai M. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2024–2032. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02894-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascoal P.M., Alvarez M.-J., Pereira C.R. Development and initial validation of the Beliefs about Sexual Functioning Scale: a gender invariant measure. J Sex Med. 2017;14:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascoal P.M., Rosa P.J., Silva E.P.D. Sexual beliefs and sexual functioning: the mediating role of cognitive distraction. Int J Sex Heal. 2018;30:60–71. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurent S.M., Simons A.D. Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety: Conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forbes M.K., Schniering C.A. Are sexual problems a form of internalizing psychopathology? A structural Equation Modeling analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:23–34. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargreaves J., Davey C., Auerbach J. Three lessons for the COVID-19 response from pandemic HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:309–311. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiefer L., Hall M., Travis C. Beyond dysfunction: a new view of Women’s sexual problems. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:225–232. doi: 10.1080/00926230252851357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tiefer L. Beyond the medical model of women’s sexual problems: a campaign to resist the promotion of “female sexual dysfunction.”. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2010;25:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dewitte M., Carvallho J., Corona G. Sexual desire discrepancy: a position Statement of the European society for sexual medicine. Sex Med. 2020;8:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atlantis E., Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1497–1507. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascoal P.M., Lopes C.R., Rosa P.J. The mediating role of sexual self-disclosure satisfaction in the association between expression of feelings and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual adults. Rev Latinoam Psicol. 2019;51:74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metz M.E., Epstein N. Assessing the role of relationship conflict in sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:139–164. doi: 10.1080/00926230252851889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehmiller J.J., Garcia J.R., Gesselman A.N. Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leis Sci. 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lomanowska A.M., Guitton M.J. Online intimacy and well-being in the digital age. Internet Interv. 2016;4:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weir K. The ascent of digital therapies. Monitor Psychol. 2018;49:80. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirana P.S., Gudeloglu A., Sansone A. E-Sexual health: a position Statement of the European society for sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1246–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wind T.R., Rijkeboer M., Andersson G. The COVID-19 pandemic: the ‘black swan’ for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interv. 2020;20:100317. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karyotaki E., Ebert D.D., Donkin L. Do guided internet-based interventions result in clinically relevant changes for patients with depression? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Topooco N., Riper H., Araya R. Attitudes towards digital treatment for depression: a European stakeholder survey. Internet Interv. 2017;8:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]