Introduction

Since the first reported Brazilian case with COVID-19 on February 26th, Brazil has presented as one of the countries with the highest number of cases and deaths. We describe a Brazilian patient with Multiple Myeloma (MM) that confirmed second COVID-19 episodes after 126 days and use of Bortezomib, Glucocorticoid and Daratumumab.

Case report

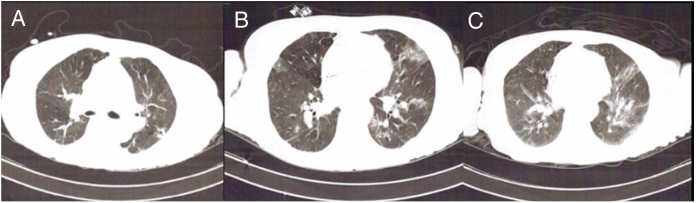

A 76-year-old female patient with end-stage kidney disease related to Lambda Light Chain MM diagnosed in November 2019. Before diagnosis, she had presented fatigue, bone pain, weigh loss (22 Kg) and hemodialysis replacement since February 2019. She presented International Staging System III and Durie Salmon stage IIIB. Systemic Arterial Hypertension and Glucose Intolerance were reported as medical history. She was considered fragile (Myeloma Frailty Score: 3) and Bortezomib and Dexamethasone (BD) were prescribed due to hypercalcemia, anemia, renal impairment, and lytic lesions. On April 21st 2020, after six BD cycles, she was admitted at emergence service with confusion and hip pain. After four days, she presented respiratory distress and COVID-19 was diagnosed by nasal swab real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) SARS-COV-2 on April 24th 2020 (Fig. 1A). She was also diagnosed with plasmacytoma in left hip during hospitalization.

Fig. 1.

(A) Computed tomography (CT) showing peripheral ground-glass opacities in the upper lobes less than 25% of pulmonary parenchyma – 24-April-2020; (B) CT showing peripheral ground-glass opacities less than 25% of pulmonary parenchyma – 28-Aug-2020; (C) CT showing peripheral ground-glass opacities in 50% of pulmonary parenchyma – 10-Sep-2020.

The patient had mild symptoms and she was submitted to clinical, transfusion and pain control support. In addition, she received antibiotic therapy with Ceftriaxone and Vancomycin for seven days. She was discharged on April 28th 2020.

Seventeen days after the first positive swab, the patient was submitted to a new RT-PCR test. Although RT-PCR SARS-COV-2 detected on May 11th, she partially recovered symptoms and maintaining sporadic delirium.

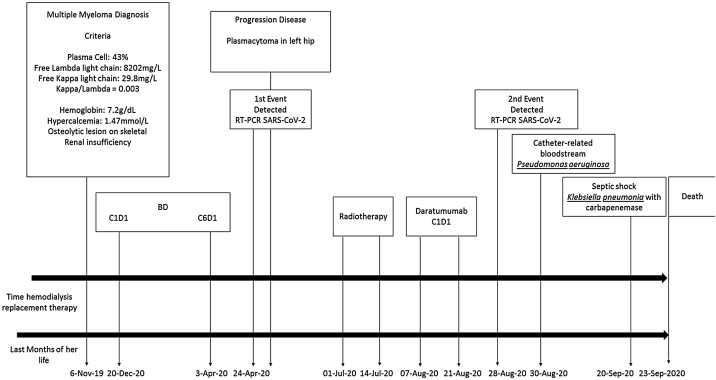

She was also referred for radiotherapy after six subsequent BD cycles attributable to plasmacytoma in left hip. She was treated with radiotherapy 3000cGy and Daratumumab monotherapy started on August 07th 2020 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Illustration about last months of her life and several events related diagnosis, treatment, COVID-19 events, and bacterial infections.

Second infusion was delayed due to chills and tremors on hemodialysis. After recovered symptoms and negative blood culture, Daratumumab was infused. After one week of Daratumumab administration, she developed dyspnea. She went to the emergency room with acute respiratory failure and hypoxemia. On August 28th, after testing, COVID-19 was positive again by nasal swab RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). Test was repeated and confirmed after 3 days. According to symptoms we considered COVID-19 reinfection. At this moment, she presented negative serology for SARS-COV-2 IgG and IgM. During the second COVID-19 infection, it was found that close family members were also infected by SARS-COV-2.

Moreover, Shilley catheter-related bloodstream infection was diagnosed. Pseudomonas aeruginosa with extended spectrum beta-lactamase was isolated in blood culture. In the beginning, she was treated with Meropenen, Vancomycin, Dexamethasone and catheter exchanged. She evolved with clinical stability, despite worse Chest Computer Tomograph (Fig. 1C). On September 17th, she developed a new febrile event and it was escalated antibiotics with Polymixicin and Linezolid. After that, RT-PCR SARS-COV-2 was performed and it was undetectable, on September 18th.

Two days later, she presented hemodynamic instability, and a new refractory septic shock and Klebsiella pneumonia with carbapenemase was identified in blood culture. She needed intensive care, mechanical ventilation, and high-dose vasoactive drug. On September 23rd she died due to complications related to COVID-19 inpatient regimen (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised several questions, one of these is if SARS-COV-2 infection induce immunity against virus, mainly in vulnerable patients that need to restart anti-neoplasm treatment after COVID-19 infection. Thus, it is important to report suspicious reinfection or reactivation COVID-19.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published report describing a patient with MM that had experienced two separate symptomatic COVID-19 confirmed by two RT-PCR each event, after resuming anti-cancer treatment with Daratumumab.

Second COVID-19 infection has been reported in few papers all of the world1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and recently in Brazil.5 However, considering the high number of recovered patients and rapidly spreading pandemic, it is crucial to highlight that reinfection and/ or reactivation are extremely rare events. Probably, these could be explained by immunity loss and/or high exposure of close contacts.

Patients with active MM present severe impairment to humoral immunity, due to disability of normal immunoglobulin production, with a concomitant secretion of monoclonal component. In addition, it was evidenced dysfunctional cellular and reduction of innate immunity, these damages promote failure of immunosurveillance mechanisms becoming patients particularly susceptible to viral and bacterial infections.7, 8 The vulnerability of this case may be explained through a Spanish multicenter case-series paper. It was observed in 167 hospitalized patients with MM and COVID-19 50% higher mortality rate than inpatient noncancer patients with COVID-19, 34% × 23%, respectively. Moreover, they were demonstrated that uncontrolled MM and renal insufficiency were independent factor of death in hospitalized patients with COVID19.9 Besides, this case presented poor prognostic factor: age >65 years, progressive disease, and renal disease.

Even though patient was fragile at high risk to COVID19 era, she was considered high priority for treatment to MM by adapted recommendations and treatment should not be postponed for relapsed/refractory patients with SLiM CRAB - guideline ESMO recommendation.10

According to treatment performed, Glucocorticoids have well-defined immunosuppressive effects, such as Bortezomib that may induce T-cell dysfunction with risk of varicella-zoster virus reactivation.11 Daratumumab is a human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that targets CD38. Although, this drug was useful against MM due to CD38 expression on clonal plasma cell, others immune cells such as monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, granulocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells presented expression levels of CD38 depended on the stage of maturation and/or activation of the cell.12 Thus, it is possible that Daratumumab, Bortezomib and Glucocorticoid could impair viral clearance and favor SARS-COV-2 reactivation. Reactivation hypothesis could be argued, mainly because this case did not present negative RT-PCR sampling after first episode and no detected anti-SARS-COV-2 (IgM and IgG).

Although, viral culture and genotype RNA were not performed, reinfection could be plausible based on the long time, 126 days, after resolution of the first infection, absent of antibodies and epidemiological history.13

The possibility of a reinfection and/or reactivation of SARS-COV-26 could be consider for immunosuppressive patients with Hematologic malignancies mainly for those that need to resume anti-cancer treatment. After quarantine isolation of 14 days, it is not clear, if it is necessary negative PCR test and/ or positive antibodies previous to restart immunosuppressive drugs to prevent second COVID-19 infectious or to avoid spreading virus in Cancer Treatment Center.

Therefore, this case report presents evidence second COVID-19 infection. Although it is rare, it could be possible, mainly in immunosuppressive patients. Thus, it is necessary to pay attention to the history of suspicious exposition and one COVID-19 event does not exclude a possible second infection.

References

- 1.Ye G., Pan Z., Pan Y., Deng Q., Chen L., Li J. Clinical characteristics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reactivation. J Infect. 2020;80(5):e14–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravioli S., Ochsner H., Lndner G. Reactivaction of COVID-19 pneumonia: a report of two cases. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e72–e73. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loconsole D., Passerini F., Palmieri V.O., Centrone F., Sallustio A., Pugliese S. Recurrence of COVID-19 after recovery: a case report from Italy. Infection. 2020;16:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01444-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou L., Liu K., Liu H.G. Cause analysis and treatment strategies of “recurrence” with novel coronavirus (COVID-19) patients after discharge from hospital. J Tuberc Respi Dis. 2020;43(4):2811–2814. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200229-00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonifacio L.P., Pereira A.P.S., Araujo D.C.A., Balbão V.M.P., Fonsenca B.A.L., Passos A.D.C. Are SARS-COV-2 reinfection and Covid-19 recurrence possible? A case report from Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200619. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0619-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gousseff M., Penot P., Gallay L., Batisse D., Benech N., Bouiller K. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81:821–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt G., Goodyear O., Moss P. Immunodeficiency and immunotherapy in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frassanito M.A., Cusmai A., Dammacco F. Deregulated cytokine network and defective Th1 immune response in multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:190–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Lopez J., Mateos M.V., Encinas C., Sureda A., Hernández-Rivas J.Á, Guia A.L.I. Multiple myeloma and SARS-CoV-2 infection: clinical characteristics and prognosis factors of inpatient mortality. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(10):103. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-00372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/haematological-malignancies-multiple-myeloma-in-the-covid-19-era Accessed on November 27th, 2020.

- 11.Basler M., Lauer C., Beck U., Groettrup M. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib enhances the susceptibility to viral infection. J. Immunol. 2009;183:6145–6150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malavasi F., Deaglio S., Funaro A., Ferrero E., Horenstein A.L., Ortolan E. Evolution and function of the ADP ribosyl cyclase/CD38 gene family in physiology and pathology. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:841–886. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling Y., Xu S.B., Lin Y.X., Tian D., Zhu Z.Q., Dai F.H. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(9):1039–1043. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]