Abstract

Introduction

This study seeks to determine the utility of D-dimer levels as a biomarker in determining disease severity and prognosis in COVID-19.

Methods

Clinical, imaging and laboratory data of 120 patients whose COVID-19 diagnosis based on RT-PCR were evaluated retrospectively. Clinically, the severity of COVID-19 was classified as noncomplicated or mild or severe pneumonia. Radiologically, the area of affected lungs compatible with viral pneumonia in each patient's computed tomography was classified as either 0–30% or ≥ 31% of the total lung area. The D-dimer values and laboratory data of patients with COVID-19 were compared with inpatient status, duration of hospitalization, and lung involvement during treatment and follow-up. To assess the predictive value of D-dimer, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted.

Results

D-dimer elevation (> 243 ng/ml) was detected in 63.3% (76/120) of the patients. The mean D-dimer value was calculated as 3144.50 ± 1709.4 ng/ml (1643–8548) for inpatients with severe pneumonia in the intensive care unit. D-Dimer values showed positive correlations with age, duration of stay, lung involvement, fibrinogen, neutrophil count, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR). When the threshold D-dimer value was 370 ng/ml in the ROC analysis, this value was calculated to have 77% specificity and 74% sensitivity for lung involvement in patients with COVID-19.

Conclusion

D-Dimer levels in patients with COVID-19 correlate with outcome, but further studies are needed to see how useful they are in determining prognosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, D-dimer, Pulmonary embolism, Severity

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization officially named the novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. The first COVID-19 case in Turkey was detected on March 11, 2020 [2]. The clinical findings of COVID-19 are generally reported as high fever, weakness, muscle pain, dry cough and shortness of breath [2,3]. Lab markers can vary, with lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia observed in severe cases [3,4]. The diagnosis of 2019-novel coronavirus can be made by reverse-transcriptase polymerase-chain reaction (RT-PCR). Computed tomography (CT) findings include peripheral ground glass densities in which multilobar, lower lobes and posterior segments are retained and sometimes accompanied by subsegment patchy consolidations [5]. Coagulopathy is present in COVID-19, and 81% of nonsurviving patients have been reported to have D-dimer levels higher than 1 ng/ml. [4,6]. In patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the D-dimer level is reported to be high, functioning as a prognostic biomarker [7,8]. This study seeks to determine the utility of D-dimer levels as a biomarker in determining disease severity and prognosis in COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Study group

Our study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Pamukkale University. COVID-19 patients were assessed retrospectively after their diagnosis was confirmed by RT-PCR in the emergency department (ED) of Pamukkale University, which was the primary center designated for the treatment of COVID-19 patients in Denizli between March 15 and April 30, 2020. The diagnosis and treatment of these patients were performed in line with the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines (Apr 14. Ed.) published by the National Health Commission of Turkey [9]. Those with oncological, hematological, chronic liver and kidney diseases, pregnancy or surgery or trauma in the last 4 weeks were excluded from the study. A standardized abstraction tool was created for data collection of demographic characteristics, comorbidities, imaging, and the results of the laboratory tests of the enrolled patients. All the above-stated data were gathered from an electronic medical records network utilized by our institutional system. We contacted 5 participants and their physicians to fill out the missing values required for the study; thus, no data were missing during the study. The interrater reliability rate was not calculated since this clinical trial was a single-blind study. Data on demographic characteristics, comorbidities, imaging, and results of the laboratory tests of enrolled patients were collected from an electronic medical records network used by our institution's system. The charts were reviewed and analyzed by a radiologist and three emergency medicine doctors. Before starting this study, an extensive study plan was constructed. No preliminary trials were required. Demographic, clinical, imaging, and laboratory data of 120 patients aged between 18 and 99 (71 males, 49 females, median 45 years, mean 48.61 ± 19.22 years) whose COVID-19 diagnosis was validated by the RT-PCR test were evaluated retrospectively.

2.2. Laboratory data analysis

Peripheral blood sampling was performed for COVID-19 patients' complete blood count and biochemical and coagulation parameters. White blood cell count and neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet counts in the complete blood count were recorded for the study. In the biochemical analysis of patients, D-dimer values were recorded with coagulation parameters. The type of D-dimer utilized is D-dimer units (DDU), and the D-dimer level was tested through an immunoturbidimetric assay within the reference range of 0–243 ng/ml in our clinical laboratory. These laboratory data were compared with the inpatient status during the treatment and follow-up periods and with inpatient department and length of stay if hospitalization was required.

2.3. Imaging

The computerized tomography scanners were a 16-slice helical CT scanner (Brilliance; Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA) and a 2-slice helical CT scanner (GE Brivo, Milwaukee, USA), both of which were operated only for COVID-19 patients during the pandemic period by taking the required disinfection and isolation measures. CT examinations were carried out between the patient and the shooting technician without resorting to intravenous contrast media by following social distance and isolation measures. CT images of all the patients were evaluated on the workstation in mediastinal (WW: 350, WL: 50) and parenchymal (WW: -600, WL: 1600) window settings by a board-certified radiologist. CT examination was performed in all COVID-19 patients by following the isolation rules. For the subjects in whom D-dimer elevation was detected in the absence of typical clinical signs of pulmonary embolism (PE), venous Doppler ultrasound examination was performed to investigate deep vein thrombosis (DVT), frequently found in the etiology of D-dimer elevation. When PE was suspected, a contrast-enhanced CT angiography scan was performed following the CT scan. Doppler ultrasound was preferred only for patients with high clinical suspicion of PE/DVT.

2.4. Severity assessment

Clinically, the severity of COVID-19 was classified as noncomplicated or mild or severe pneumonia under the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines (4th Ed.) by the National Health Commission of Turkey (Table 1 ) [9]. Radiologically, the area of affected lungs consistent with viral pneumonia in each patient's first chest CT after admission was measured and classified into 0–30% (common type) or ≥ 30% (severe-critical type) of the total lung area [10].

Table 1.

Clinical classification of COVID-19 patients included in the study

| Non-complication group | Mild group | Severe group |

|---|---|---|

| a. patients reported symptoms such as fever, muscle / joint pain, cough, sore throat and nasal congestion without respiratory distress, tachypnea or SPO2 < 93%, b. patients without comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cancer, chronic lung diseases or other immunosuppressive conditions or under 50 years of age c. patients with normal chest radiography or thoracic tomography. |

a. patients reported symptoms such as fever, muscle / joint pain, cough, sore throat and nasal congestion, with a respiratory rate < 30 / minute, SpO2 level above 90% in the room air. b. patients with signs of pneumonia on chest radiography or thoracic tomography. |

a. patients reported symptoms such as fever, muscle / joint pain, cough, sore throat and nasal congestion, respiratory distress, tachypnea (≥30 / minute) or SpO2 level in room air is below 90% b. patients with signs of pneumonia on chest radiography or thoracic tomography or patient with acute organ dysfunction. |

2.5. Statistics

Continuous data with a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared by independent samples t-tests. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentages) and were compared by chi-square tests. To assess the predictive value of D-dimer, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted with calculations of the area under the ROC curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity. The statistical analyses were run in SPSS 21 for Windows (Chicago, IL), and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 120 subjects diagnosed with COVID-19 between March 15 and April 30, 2020 were classified clinically and radiologically. A total of 67.5% of the patients were afflicted with at least one comorbid condition, including hypertension (31.7%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (15%), coronary artery disease (12.5%), and chronic kidney injury (8.3%). Seventy-three patients (60.8%) were hospitalized and followed-up in the COVID-19 service, while 18 patients (15%) were hospitalized in the intensive care unit. The average length of hospital stay was 9.09 (2–35) days. Twenty-nine patients were followed-up at home through contact tracing by recommending compliance with isolation conditions (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Study group descriptive features

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 49 | 40,8 |

| Male | 71 | 59,2 | |

| Inpatient Groups | 0–5 Days | 26 | 28,6 |

| 6–10 Days | 39 | 42,9 | |

| 11 Days and more | 26 | 28,6 | |

| Inpatient Department | No | 29 | 24,2 |

| Service | 73 | 60,8 | |

| ICU | 18 | 15,0 | |

| CT Scan | Performed | 15 | 12,5 |

| Unperformed | 105 | 87,5 | |

| Involvement Group | Under 30% | 74 | 70,5 |

| Over 30% | 31 | 29,5 |

N = Number of patient, CT = Computerized Tomography, ICU=Intensive care unit.

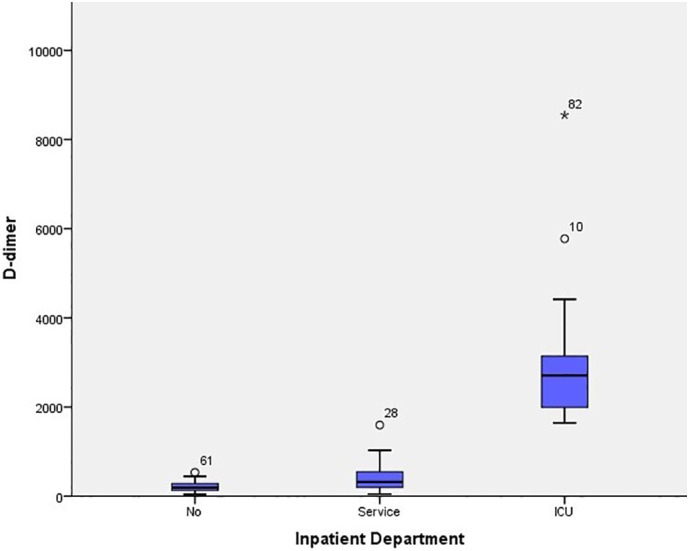

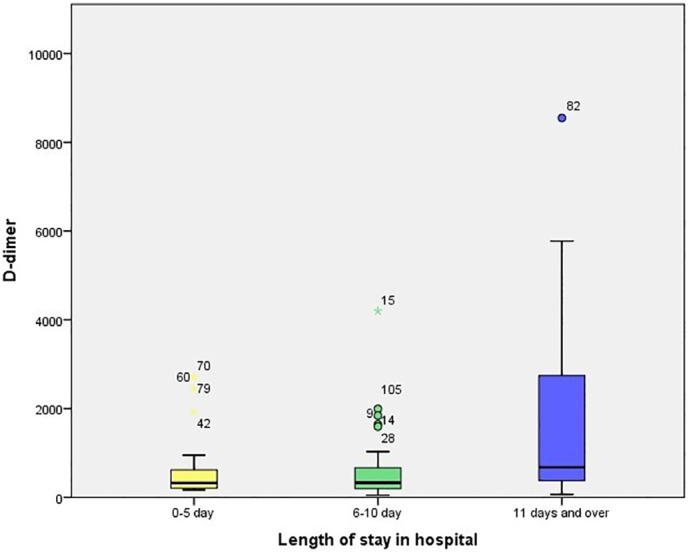

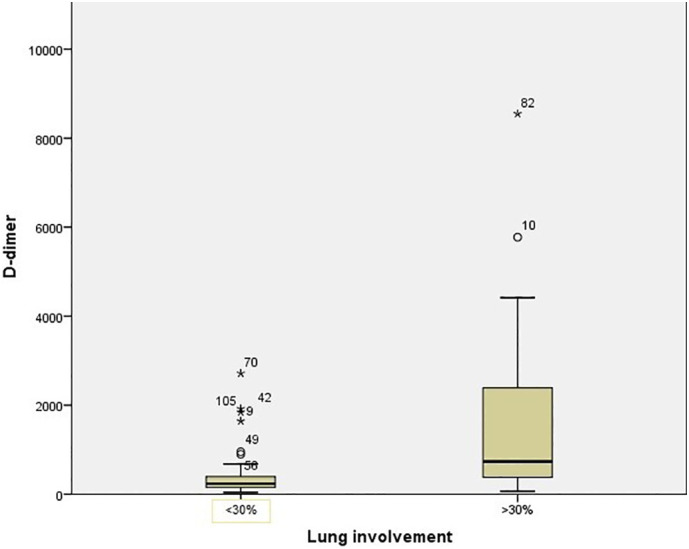

The patients were clinically divided into three groups: noncomplicated, mild and severe pneumonia. Of 120 patients included in the study, 24.2% (29/120) were identified as noncomplicated, 60.8% (73/120) as mild, and 15% (18/120) as severe. D-Dimer elevation (> 243 ng/ml) was detected in 63.3% (76/120) of the patients, and this rate tended to increase as their clinical condition worsened. The mean D-dimer value was calculated as 3144.50 ± 1709.4 ng/ml (1643–8548) for inpatients with severe pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Furthermore, thorax CT results were obtained from 105 patients included in the study. Accordingly, 70.5% (74/105) of the patients suffered lung involvement <30%, while 29.5% (31/105) had lung involvement >30%. In the patients with severe lung involvement, there were significant differences between D-dimer, fibrinogen, neutrophil, and lymphocyte levels compared with those with mild or no involvement. Similarly, significant differences were observed between the patients in the intensive care unit and those without intensive care unit hospitalization in terms of D-dimer, fibrinogen, neutrophil, and lymphocyte levels. Lung involvement and length of hospital stay were significantly higher in older patients than in their younger counterparts (Table 3 ) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ).

Table 3.

Relation of lung involvement and ICU hospitalization with other variables

| Lung involvement |

ICU |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 30% |

Over 30% |

p | No |

Yes |

p | |||||

| Mean ± SD | Med (min - max) | Mean ± SD | Med (min - max) | Mean ± SD | Med (min - max) | Mean ± SD | Med (min - max) | |||

| Age | 45.26 ± 17.48 | 43 (21–85) | 60.29 ± 18.91 | 62 (23−100) | 0.0001⁎ β | 45.91 ± 18.51 | 44 (18–100) | 63.89 ± 16.18 | 64.5 (37–87) | 0.0001⁎ β |

| Length of stay | 7.26 ± 3.53 | 6.5 (3−21) | 11.97 ± 7.47 | 10.5 (2–35) | 0.0001⁎ β | 2.56 ± 3.43 | 1 (0−11) | 8.47 ± 5.11 | 8 (0−20) | 0.0001⁎ β |

| Lung involvement | ||||||||||

| D-dimer | 378.2 ± 453.62 | 237 (39–2714) | 1636.1 ± 1932.22 | 732 (66–8548) | 0.0001⁎ β | 340.71 ± 258.55 | 265 (39–1596) | 3144.5 ± 1709.4 | 2706 (1643–8548) | 0.0001⁎β |

| Fibrinogen | 401.97 ± 223.04 | 298 (173–1008) | 479.17 ± 175.78 | 458.5 (167–906) | 0.035 β | 410.18 ± 214.49 | 324.5 (173–1008) | 508.29 ± 189.54 | 503.5 (167–906) | 0.048⁎ β |

| Neutrophil | 6 ± 2.25 | 5.57 (2.46–12.18) | 7.95 ± 5.15 | 6.23 (2.43–27.87) | 0.061 β | 5.94 ± 2.24 | 5.42 (2.43–12.18) | 10.72 ± 5.97 | 9.29 (5.25–27.87) | 0.0001⁎ β |

| Lymphocyte | 1.75 ± 0.71 | 1.73 (0.51–3.88) | 1.21 ± 0.54 | 1.14 (0.45–2.67) | 0.0001⁎ β | 1.69 ± 0.74 | 1.63 (0.51–4.27) | 1.21 ± 0.59 | 1.17 (0.45–2.47) | 0.007⁎ β |

| Platelet | 253.18 ± 54.88 | 244 (145–384) | 239.13 ± 66.18 | 250 (112–356) | 0.265 α | 252.13 ± 58.09 | 245 (145–426) | 237.17 ± 73.82 | 246.5 (112–365) | 0.337 α |

ICU=Intensive care unit.

p < 0.05 statistically significant; α: Inpendent samples t-test; β: Mann Whitney U test.

Fig. 1.

Box plot chart showing the D-dimer value relationship according to patient hospitalization.

Fig. 2.

Box plot chart showing the D-dimer value relationship by length of hospital stay.

Fig. 3.

Box plot chart showing the D-dimer value relationship with lung involvement in CT.

D-Dimer values were concluded to be positively correlated with age, length of stay, lung involvement, fibrinogen, and neutrophil count but negatively correlated with lymphocyte count (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Correlation between D-dimer and variables

| Age | Length of stay | Lung involvement | Fibrinogen | Neutrophil | Lymphocyte | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-dimer | R | 0.422⁎⁎ | 0.254⁎ | 0.416⁎⁎ | 0.407⁎⁎ | 0.481⁎⁎ | −0.535⁎⁎ |

| p | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 statistically significant; Spearman Correlation Coefficient.

When the threshold D-dimer value was set as 370 ng/ml in the ROC analysis, this value for any lung involvement was calculated to have a specificity of 77% and a sensitivity of 74% in COVID-19 patients. When the threshold D-dimer value was 370 ng/ml, the area under the ROC curve (Az) was 0.813 (95% confidence interval, 0.722–0.904) (Fig. 4 ). The positive likelihood ratio was 3.2, and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.34.

Fig. 4.

The D-dimer value for lung involvement was 370, and the area under the ROC curve (Az) was 0.813 (95% confidence interval, 0.722–0.904).

4. Discussion

This is a single-center, retrospective study focusing on cases who presented to a tertiary hospital and were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 by means of RT-PCR. This cohort study seeks to determine the utility of D-dimer levels as a biomarker in determining disease severity and prognosis in COVID-19. In hemostasis, the formation of fibrin clots in response to vascular damage from the coagulation system is balanced by the breakdown of coagulation by the fibrinolytic system. D-Dimer is a fibrin degradation product resulting from the sequential cleavage of the fibrinogen formed in the coagulation system by the fibrinolytic system. It is generally involved in the diagnostic algorithm of thrombosis and thrombosis-conditioned pathologies (DVT, PE, to name a few). However, D-dimer elevation can be observed physiologically or pathologically, as in malignant diseases, chronic liver diseases, postoperative conditions, pregnancy and inflammation and infection conditions. Our study revealed that D-dimer elevation was common among patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and associated with disease severity.

Even though PE/DVT was not diagnosed in our patients, D-dimer elevation was observed in 61.7%. D-Dimer was not previously considered a biomarker in viral or bacterial pneumonia. D-Dimer has recently been reported to be elevated in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, and there are many studies that suggest correlations with D-dimer elevation and disease severity. Examining 41 COVID-19 patients clinically and through laboratory tests, Huang et al. reported that those with severe conditions had D-dimer values 5 times higher than those of the other patients [11]. In another study with 183 COVID-19 patients, Tang et al. concluded that the D-dimer level was approximately 3.5 times higher in patients with severe conditions than in their nonsevere counterparts [12]. In a retrospective study by Yao et al. analyzing the clinical and radiological findings of 248 COVID-19 patients in a hospital in Wuhan, they reported that D-dimer levels were significantly higher in patients with severe conditions than in other patients [13]. In another study, Yu et al. concluded that D-dimer levels were significantly elevated in 57 patients with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia and in 46 patients with confirmed community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CAP) and that D-dimer was elevated to higher levels in COVID-19 patients [14].

As far as the aforementioned studies are concerned, the D-dimer levels of patients with severe conditions were reported to be significantly higher than those of mild and moderate patients. Given the most recent data in the literature, D-dimer values are frequently increased in 36–43% of COVID-19 patients [15]. In our study, we observed clinically and radiologically that patients with more extensive pneumonia manifested higher D-dimer levels than those without or with less extensive pneumonia. Our results suggest that D-dimer levels may assist in assessing severity and morbidity in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathological features of COVID-19 include alveolar damage, desquamation of pneumocytes, hyaline membrane formation, pulmonary edema and interstitial mononuclear inflammatory leaks. Disorders in the hemostasis cascade coupled with increased inflammatory load and hyperfibrinolysis lead to elevated D-dimer levels and greater lung involvement [16,17]. Patients with high D-dimer levels have longer hospitalizations in intensive care units and lengths of hospital stay [6].

In COVID-19, lymphocytes are decreased and neutrophils are increased among patients who suffer from severe symptoms clinically and radiologically and manifest lung findings due to increased serum cytokines and chemokines [18,19].

Qu et al. suggested that age and platelet levels of COVID-19 inpatients correlated positively with the length of hospital stay but negatively with lymphocyte levels [20]. Patients with severe pneumonia who were in the intensive care unit had D-dimer levels that were twice those of other patients.

In the report by Aggarwal et al., 16 patients with a definitive diagnosis of COVID-19 were included. The clinical and laboratory features of these patients were examined. In their study, which did not analyze D-dimer values, chest CT was performed in 44% of the patients (7 patients), and multifocal ground-glass opacity was observed in all of them. In our study, chest CT was performed in 87.5% (105/120) of the patients, and only 29.5% (31/105) of them manifested lung involvement above 30%. This can be explained by the general condition of most patients included in the study of Aggarwal et al., who needed intensive care units and mechanical ventilation [21].

4.1. Limitations

We realize that several limitations might have influenced the results obtained in our study. First, since this is a retrospective study, the results and clinical follow-ups were accessed from the hospital registration system without seeing the patients; thus, additional laboratory examinations could not be conducted. Second, only the clinically suspected patients among the study population were taken into consideration for PE/DVT. Third, the follow-up of our patients' CT findings could not be repeated in terms of radiation exposure. Fourth, data on the intubation status of the patients, their health status after discharge, and their survival status could not be obtained. Fifth, a single reviewer abstracted the data. Sixth, this study utilized early generation CT scanners, rather than later generation CT scanning technology. Finally, the findings presented in this study were obtained only from a limited number of patients presenting to the ED.

5. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia is closely associated with D-dimer levels, which tended to increase as the clinical or radiological conditions of patients with COVID-19 worsened. We are of the opinion that D-dimer levels in patients with COVID-19 correlate with outcome, but further studies are needed to see how useful they are in determining prognosis.

Author contribution statement

1-Study concept and design: M.O. and A.Y. 2-Acquisition of data: M.O., A.Y., A.O., M.S., and R.B. 3-Analysis and interpretation of data: H.S., A.Y., and V.C. 4-Drafting of the manuscript: M.O. and A.Y. 5-Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.O., A.Y., A.O., M.S., and R.B. 6-Statistical analysis: H.S., A.Y. and V.C. 7-Administrative, technical and material support: A.O., M.S., and R.B. 8-Study supervision: M.O., A.Y., and V.C.

Compliance with ethical standards

Pamukkale University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee was approved for the study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and no grants or funds were received in this study.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020 (WHO, 11 February 2020).

- 2.Turkish Government Ministry of Health. 2020. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/ Available from:

- 3.Ei Azhar, Hui D.S.C., Memish Z.A., Drosten C., Zumla A. The Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:891–905. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salehi S., Abedi A., Balakrishnan S., Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;2020:1–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID–19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Querol-Ribelles J.M., Tenias J.M., Grau E., Querol-Borras J.M., Climent J.L., Gomez E. Plasma d-dimer levels correlate with outcomes in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2004;126:1087–1092. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snijders D., Schoorl M., Schoorl M., Bartels P.C., van der Werf T.S., Boersma W.G. D-dimer levels in assessing severity and clinical outcome in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A secondary analysis of a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVİD-19 (Sars-Cov-2 ENFEKSİYONU) Rehberi. 14 April 2020. Available from. https://covid19bilgi.saglik.gov.tr/depo/rehberler/COVID-19_Rehberi.pdf

- 10.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinese Society of Radiology Chinese Medical Association Radiology Branch. Radiological diagnosis of novel coronavirus pneumonia: expert recommendations from Chinese society of radiology. Chin J Radiol. 2020;54:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Y., Cao J., Wang Q., Liu K., Luo Z., Yu K. 2020. D-dimer as a biomarker for disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a case control study. Critical Care & Emergency Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu B., Li X., Chen J., Ouyang M., Zhang H., Zhao X. Evaluation of variation in D-dimer levels among COVID-19 and bacterial pneumonia: a retrospective analysis. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02171-y. Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippi G., Plebani M. Laboratory abnormalities in patients with COVID-2019 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020 doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C. Pathological findings of COVID–19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin C., Zhou L., Hu Z., Zhang S., Yang S., Tao Y. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;7:91.96.:91–96. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qu R., Ling Y., Zhang Y.H. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease-19. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal S., Garcia-Telles N., Aggarwal G., Lavie C., Lippi G., Henry B.M. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis. 2020;7:91–96. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]