Black salve is an indiscriminate escharotic, usually applied topically, that typically combines the corrosive compounds bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) and zinc chloride. Topical formulations of black salve are sold over the counter under various commercial names other than black salve [1]. While not approved by the US FDA, black salve is advertised by marketers as safe and effective in the treatment of cancer, boils, bug bites, warts, moles, and skin tags. It allegedly targets diseased cells, leaving healthy tissue unharmed [1, 2]. Some homeopathic products include S. canadensis and zinc chloride or list them as inactive ingredients. However, these agents are corrosive, and FDA defines inactive ingredients as a “harmless drug that is ordinarily used as an inactive ingredient” (e.g., coloring, excipient) [3].

In the 1930s, Dr. Frederic Mohs combined S. canadensis with zinc chloride and antimony trisulfide, creating a fixative paste to prepare a skin cancer for surgical excision [2]. Mohs later decried using escharotics alone because of the risk of disfigurement and unreliability of cure [4]. Mohs’ technique evolved, seeing the paste replaced with sequential fresh frozen tissue sampling until margins are tumor free [5]. Mohs’ micrographic surgery, a single-day tissue-preserving procedure, is now the standard of care for high-risk, locally invasive skin cancers. Unfortunately, Mohs’ original work may be conflated with the modern surgical technique, leading to a misperception that black salve is a legitimate skin cancer treatment [6].

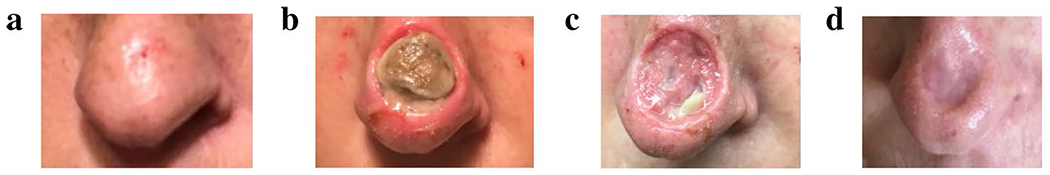

We received a case in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database describing cosmetic disfigurement with black salve. A 50-year-old female self-treated a skin lesion on her nose with a topical black salve product, which she purchased online after researching the product and perceiving it to be safe. For 6 days, she applied the product to the lesion, along with petrolatum and an occlusive dressing. Upon noticing an erosion, she contacted the company selling the product, which informed her the product was working as expected. She then consulted a plastic surgeon, who advised her that surgical intervention was not feasible because of the “thin skin” on her nose. The eroded area was treated with azithromycin, bacitracin, and triamcinolone. Unfortunately, the result was permanent cosmetic disfigurement. Figure 1 depicts the tissue injury, which is similar in appearance to the subject of another report in the medical literature by Osswald et al. [7]. In 2019, the maker of the black salve product issued a voluntary recall of the product because it was being marketed without an approved new drug application (NDA)/abbreviated NDA, and because it contained ingredients that FDA has determined to be caustic in nature and that can cause serious injury [8].

Fig. 1.

Sequential photos of skin injury from the topical black salve product: Before (a) and after (b–d) use of black salve

This case prompted a search of the FAERS database through 31 July 2020 for other reports of clinically significant adverse events following exposure to black salve. We identified six cases involving one male and five females (see Table 1), including the case described. The mean age was 59 years. Reported reasons for use were undiagnosed skin lesion or cancer. Duration of use ranged from 1 to 16 days. Adverse events were consistent with published reports describing burn [9, 10], infection [9, 11], interference with diagnosis and staging of cancer [9, 12, 13], localized pain [7, 9, 14, 15], residual tumor [11, 16–18], and other tissue injury [6, 9, 12–14, 16,18–20]. One FAERS case came from a physician who identified a melanoma in situ, confirmed by biopsy, adjacent to a lesion that had been destroyed by black salve, making accurate diagnosis and staging of a potentially invasive melanoma impossible. Reported treatments from the case series included reconstructive surgery, removal of residual tumor, aggressive debridement, local wound care, topical corticosteroids, and antibiotics.

Table 1.

US FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) cases describing disfigurement related to a black salve product

| Case | Received by FDA (year) | Product source | Reason(s) for use | Patient age (years); sex | Adverse event(s) | Duration of use (days) | Physician diagnosis after use | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2019 | Internet | Undiagnosed skin lesion; “Flake-like spot on her nose” | 50; F | Tissue necrosis with permanent cosmetic disfigurement | 6 | NR | Local wound care, oral antibiotics, topical corticosteroid |

| 2 | 2019 | Internet | Undiagnosed skin lesion: “Presumed moles” | 73; M | Burn (chemical); interference/delay in diagnosis/staging; residual localized tumor; scar | NR | Melanoma in situ | Removal of residual tissue at site |

| 3 | 2018 | Internet | NR | NR; F | Tissue necrosis; burn; scar | 1 | NR | Ice, unspecified medicine, washed area |

| 4 | 2015 | Large retailer | Undiagnosed skin lesion; “anti-cancer agent” (naturopath advised use) | 65; F | Tissue necrosis (“extensive”; 6 cm area) | 6 | Scar; tissue necrosis | Debridement (“aggressive”) |

| 5 | 2015 | Internet | Undiagnosed skin lesion; “unspecified” cancer | 44; F | Burn (3rd degree); eschar; infection | 3 | Scar | NR |

| 6 | 2004 | Internet | Undiagnosed skin lesion; self-diagnosed “cancerous lesion” | 65; F | Localized pain; tissue necrosis | 16 | Seborrheic keratosis; tissue necrosis | Reconstructive surgery (“baseball-sized” lesion removed requiring surgical closure) |

F female, M male, NR not reported

Our review of these cases demonstrates permanent cosmetic disfigurement with the use of black salve and other corrosive products containing S. canadensis and zinc chloride. Nevertheless, these products are advertised as low-cost, safe, effective, and/or natural (e.g., homeopathic) alternatives to conventional medical care. Even a well-informed consumer may unknowingly purchase a black salve product and experience tissue injury. Healthcare professionals should be aware of these risks and discourage patients from using black salve products.

Acknowledgments

Funding No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study or this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the US Food and Drug Administration.

Conflicts of interest Lopa Thambi, Karen Konkel, Ida-Lina Diak, Melissa Reyes, and Lynda McCulley have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material Not applicable.

Consent to publish The patient has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal and to publication of their data and photographs.

Code availability Not applicable.

Ethical approval FDA is permitted to disclose personal information with written consent of the person identified in an adverse event report. The authors have written documentation of consent for use of submitted photographs. Additional ethics approval is not considered necessary.

Consent to participate The photographed individual has provided written consent for use of the submitted information.

References

- 1.Croaker A, Lim A, Rosendahl C. Black salve in a nutshell. Aust J Gen Prac. 2018;47(12):864–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. A review of topical corrosive black salve. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(4):284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations 21CFR201.117. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=201.117. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

- 4.McDaniel S, Goldman G. Consequences of using escharotic agents as primary treatment for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1593–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nehal K, Lee E. Mohs surgery. Miller S, Corona R, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc; https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed 9 Mar 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saltzberg F, Barron G, Fenske N. Deforming self-treatment with herbal “black salve”. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(7):1152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osswald SS, Elston DM, Farley MF, et al. Self-treatment of a basal cell carcinoma with “black and yellow salve”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(3):509–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration. Company announcement. McDaniel Life-Line LLC Issues Voluntary Worldwide Recall of Indian Herb. February 08, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/mcdaniel-life-line-llc-issues-voluntary-worldwide-recall-indian-herb. Accessed 17 Aug 2020.

- 9.Saco M, Merkel K. Extensive full-thickness chemical burn caused by holistic hazard black salve [abstract no. 2331]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 Suppl 1):AB54. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worley B, Nemechek AJ, Stoler S, et al. Naturopathic self-treatment of an atypical fibroxanthoma: lessons for dermatologic surgery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(6):683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncanson A, Kopstein M, Skopit S. Advanced presentation of homeopathically treated giant melanoma: a case report. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):28–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laskey D, Tran M. Facial eschar following a single application of black salve. Clin Tox. 2017;55(7):676–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins A, Bui M, Morley K. The dangers of black salve. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):618–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan R, Costley M, O’Kane D, et al. Use of black salve for self-treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(8):947–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma L, Dharamsi JW, Vandergriff T. Black salve as self-treatment for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatitis. 2012;23(5):239–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cienki JJ, Zaret L. An internet misadventure: bloodroot salve toxicity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(10):1125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivyer G, Rosendahl C. Application of black salve to a thin melanoma that subsequently progressed to metastatic melanoma: a case study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4(3):77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozung AK, Ko AC, Gallo RA, Rong AJ. Persistent basal cell carcinoma following self-treatment with a “natural cure,” Sanguinaria canadensis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020. 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001784 [Published online ahead of print, 21 Jul 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eastman K, McFarland L, Raugi G. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):e154–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeon J, Fernandez-Penas P. Case study: potential side effects of black salve. Aust J Dermatol. 2019;60(Suppl 1):104. [Google Scholar]