Abstract

Background

Self-collection for high-risk HPV (hr-HPV) mRNA testing may improve cervical cancer screening. Hr-HPV mRNA with self-collected specimens stored dry could enhance feasibility and acceptance of specimen collection and storage; however, its performance is unknown. We compared the performance of hr-HPV mRNA testing with dry- as compared to wet-stored self-collected specimens for detecting ≥HSIL.

Methods

A total of 400 female sex workers in Kenya participated (2013–2018), of which 50% were HIV-positive based on enrollment procedures. Participants provided two self-collected specimens: one stored dry (sc-DRY) using a Viba brush (Rovers), and one stored wet (sc-WET) with Aptima media (Hologic) using an Evalyn brush (Rovers). Physician-collected specimens were collected for HPV mRNA testing (Aptima) and conventional cytology. We estimated test characteristics for each hr-HPV screening method using conventional cytology as the gold standard (≥HSIL detection). We also examined participant preference for sc-DRY and sc-WET collection.

Results

HR-HPV mRNA positivity was higher in sc-WET (36.8%) than sc-DRY samples (31.8%). Prevalence of ≥HSIL was 6.9% (10.3% HIV-positive; 4.0% HIV-negative). Sensitivity of hr-HPV mRNA for detecting ≥HSIL was similar in sc-WET (85%, 95% CI: 66–96),sc-DRY specimens (78%, 95% CI: 58–91), and physician-collected specimens (93%, 95% CI: 76–99).Overall, the specificity of hr-HPV mRNA for ≥HSIL detection was similar when comparing sc-WET to physician-collection. However, specificity was lower for sc-WET [66% (61–71)] than sc-DRY [71% (66–76)]. Women preferred sc-DRY specimen collection (46.1%) compared to sc-WET (31.1%). However, more women preferred physician-collection (63.9%) compared to self-collection (36.1%).

Conclusions

Sc-DRY specimens appeared to perform similarly to sc-WET for the detection of ≥HSIL.

Keywords: HPV mRNA, self-collection, dry stored, cervical cancer screening

Short Summary

A study of female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya found that self-collected specimens stored-dry performed similarly to specimens stored-wet for HPV mRNA testing to detect high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions.

Background

Invasive cervical cancer is caused by persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) (1). Although highly preventable through early detection and treatment of precancerous lesions(2), cervical cancer remains the fourth most common cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women worldwide(3). In high-resource countries, the successful implementation of cytology-based, or Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, screening has reduced cervical cancer incidence and mortality by at least 80% (4). However, there are several barriers to the implementation of cytology-based programs in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), including limited healthcare infrastructure, reduced access to clinicians to conduct pelvic examinations, and fewer trained cyto-pathologists (5). Consequently, the burden of cervical cancer disproportionately impacts both never- and under-screened women in LMICs, where nearly 90% of the deaths attributable to cervical cancer occur(3). In Kenya, where the estimated population-based screening coverage is 13%(6), cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women(3).

The development of molecular-based laboratory assays to detect hr-HPV has recently changed the approach to cervical cancer screening(7). Evidence from randomized controlled trials shows that primary hr-HPV screening is effective for the detection of high-grade precancerous lesions, with higher sensitivity and less frequent intervals required between screenings(7, 8). Molecular hr-HPV testing has been associated with lower mortality attributable to cervical cancer(9) and offers the potential to implement larger-scale cervical cancer screening programs using self-collected sampling(10). In accordance with World Health Organization recommendations(2), LMICs are implementing molecular HPV testing as a primary screening tool(11).

Self-collection of cervico-vaginal specimens for cervical cancer screening is a clinically valid method for hr-HPV testing, with the potential to circumvent barriers to clinic-based screening(12). Additionally, sensitivity for the detection of high-grade cervical lesions using self-collected samples for HPV DNA detection is equivalent to physician-collected samples(13). However, hr-HPV DNA testing does have limitations. For example, in populations and geographical areas where hr-HPV prevalence is high, providing HPV DNA testing may have notably low specificity for high-grade cervical lesions detection(2), resulting in unnecessary follow-up procedures, and overburdening of referral clinics for treatment(14).

One potential strategy to improve the specificity of cervical cancer screening is to test for hr-HPV mRNA of the oncogenic proteins E6 and E7, which may more accurately predict progression to invasive disease(15). Few prior studies have evaluated the validity of using self-collected samples for HPV mRNA testing(14, 16, 17). Further, currently available data evaluating self-collection for HPV mRNA testing have been generated using samples stored in liquid transport media, which is relatively more costly than dry self-collection(18).

The feasibility of self-collected sampling for hr-HPV testing with dry swabs transported and stored at room temperature might facilitate more efficient and larger scale screening strategies in LMICs. To date, there is a lack of data on the performance of self-collection using brushes stored dry (sc-DRY) compared to self-collected samples stored wet in transport media (sc-WET) to evaluate the clinical validity for high-grade cervical lesion detection. We present here results comparing the performance of Aptima hr-HPV mRNA testing (Hologic Corporation, San Diego, CA) using sc-DRY and sc-WET specimens for the detection of cytological high-grade cervical lesions or more severe (≥ HSIL) among female sex workers (FSWs) in Mombasa, Kenya. Further, we present results of the performance of Aptima hr-HPV mRNA testing for physician-collected specimens for the detection of ≥HSIL. We also evaluated participants’ preferences for HPV sampling methods.

Methods

Study Population

From August 2013 to April 2018, FSWs participating in a cohort study of women at high risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV in Mombasa, Kenya were invited to participate in this cross-sectional cervical cancer screening study to compare the performance of self-collected sampling methods stored both dry and wet, physician-collected sampling, and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) for cervical cancer screening. Clinical procedures, including self- and physician-collection of genital samples for HPV mRNA testing were performed at the Ganjoni Clinic in Mombasa. The Ganjoni Clinic has been a primary research site for the Mombasa Cohort(19) and venue for STI testing and treatment among at-risk and HIV-positive women in Mombasa for over 25 years.

Study procedures were integrated into the ongoing follow-up procedures for the Mombasa Cohort, as previously described(20). Briefly, the Mombasa Cohort is an open cohort study of FSWs established in 1993 to provide high-quality care to at-risk women and supports research efforts of HIV prevention, treatment, and care. For participant recruitment, outreach meetings were conducted at major sex work venues one to two times each month. During these meetings, outreach staff provided counseling on a health topic requested by the women of the community, as well as general information about the research clinic. Interested women were provided with a referral card and invited to visit Ganjoni Clinic.

The criterion for inclusion into the Mombasa Cohort included: 1. Women aged 18 years and above; 2. Residing in the Mombasa area; 3. Self-identifying as exchanging sex for payment in cash or in-kind at the time of enrollment and 4. Able to provide informed consent. Eligible women were invited to participate in this cervical cancer screening study during the visit for specimen collection for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae testing. We used convenience sampling to enroll women who agreed to participate from among those who were eligible and carried out enrollment to ensure half of the participants were HIV-positive. Women were excluded from this study if they were currently pregnant or had a history of hysterectomy or treatment for cervical precancer. Participating women were counseled on the risks and benefits of cervical cancers screening, and administered a questionnaire to collect socio-demographic, reproductive, and sexual behavior data. The study was approved by the ethical review committees of the University of Nairobi/Kenyatta National Hospital and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment into the study.

Sample Collection

To perform self-collection of genital specimens, each woman was directed to a private room at the clinic. A study nurse provided verbal instructions and pictorial diagrams with detailed instructions on self-collection were available in the private room. Participants were instructed to squat and insert a cytobrush up into the vaginal vault, rotating it 3–5 times, and then withdrawing. Each woman performed self-collection using two different specimen brushes: (1) the Evalyn cytobrush (Rovers®, Netherlands) for dry self-collection (sc-DRY) and (2) the Viba cytobrush (Rovers®, Netherlands) for wet self-collection (sc-WET), which included a plastic cryovial containing 1 ml of Aptima liquid transport media (Hologic®, USA) (Figure 1). The Evalyn cytobrush consists of a pink plunger containing white bristles made of polyethylene at the tip, a transparent casing, and a transparent cap (https://www.roversmedicaldevices.com/cell-sampling-devices/evalyn-brush/). The Viba brush consists of a blue handle and a removable white tip (https://www.roversmedicaldevices.com/cell-sampling-devices/viba-brush/). The tip contains bristles made of similar material as the Evalyn brush. To minimize potential bias from the order of specimen collection, women assigned odd study numbers self-collected using the Evalyn brush first, while those with even study numbers self-collected using the Viba cytobrush first.

Figure 1:

Cyto-brushes used for self-collection: Rovers® Evalyn® Brush and Rovers® Viba-Brush® RT, Rovers Medical Devices, Oss, The Netherlands

After self-collection, a study clinician performed a speculum-assisted pelvic examination to collect cervical specimens for hr-HPV mRNA testing. Physician-collection of cervical specimens from the endocervix was performed using a cervical specimen collection brush (Hologic®, USA). Similar to the Viba brush (for sc-WET), physician-collected specimens were stored in Aptima media. After specimen collection, the clinician performed visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and a conventional Pap smear for cytology assessment. All study clinicians had extensive training and experience in genital examination and specimen collection as part of the procedures in the Mombasa Cohort. Following the clinical examinations, women participated in a structured interview using a standardized questionnaire to assess their experiences undergoing self- and physician-collection of specimens.

Conventional cytological smears were evaluated at the University of Nairobi and classified according to the 2001 Bethesda System. All smears were independently read by two cyto-pathologists who were blinded to HPV mRNA and VIA screening results. For discrepant cases, the final diagnosis was made after a consensus of the two reviewing cyto-pathologists. Women with high-grade lesions or above were referred to standard care and treatment at the Coast Provincial General Hospital in Kenya. All specimens were archived for external quality control and future testing.

HPV mRNA Lab Testing

The physician-collected sample and both self-collected samples were transported daily to the research laboratory at the Coast Provincial General Hospital (CPGH) for hr-HPV mRNA testing. The physician-collected sample and both self-collected samples were transported daily to the research laboratory at the Coast Provincial General Hospital (CPGH) for hr-HPV mRNA testing. The samples were transported by project personnel in a cooler box and kept at 8°C, which was monitored by an external temperature probe. On arrival at the research laboratory, the sc-dry samples were first stored at room temperate and transferred into Aptima media no more than 12-hour post-collection. All samples were stored in a freezer at −80 °C until laboratory testing. Testing for HPV mRNA detection took place at CPGH laboratory.

Laboratory personnel were blinded to the results of the other screening tests. Self-sampled and physician-sampled genital specimens were tested for hr-HPV using the FDA-approved APTIMA® HPV Assay (Hologic Inc, San Diego, USA) which detects mRNA encoding the E6/E7 oncoproteins from 14 high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68). Specimen processing comprises three main steps including, target capture, target amplification by Transcription-Mediated Amplification (TMA), and amplicon detection by the Hybridization Protection Assay (HPA) carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This process was automated using Hologic’s Panther® System platform by trained technologists.

Statistical Analyses

Of 400 FSWs, 1 woman was missing hr-HPV mRNA testing results and excluded from analyses, resulting in a final sample of 399. Sociodemographic and sexual behavioral characteristics were assessed for all women and stratified by HIV-status using univariate analyses. Agreement between hr-HPV mRNA positivity in sc-WET specimens compared to sc-DRY and compared to physician-collection was measured using percent agreement and the κ (Kappa) statistic with 95% confidence intervals(21), stratified by cytology diagnosis. Pairwise comparisons using McNemar’s test were conducted to assess differences in hr-HPV mRNA prevalence in sc-DRY and sc-WET sample specimens and in sc-WET versus physician-collection, which is included in the Appendix (Appendix Table 1). Two-by-two tables were constructed to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) using conventional cytology as the study endpoint (≥HSIL detection) with 95% confidence intervals. Differences in sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of screening tests were assessed using Wald-type confidence intervals(22). We calculated prevalence differences (PD) with 95% confidence intervals to assess potential differences in preference of self-collection devices by age (<40 years and ≥40 years).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to estimate PPV and NPV values of sc-DRY and sc-WET specimens for varying prevalence of ≥HSIL to address concerns regarding generalizability and transportability of findings. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends cervical cancer screening to start as soon as a woman has tested positive for HIV, regardless of age(2). Therefore, we present results stratified overall, and by HIV status. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® 9.4.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Overall, the median age of women was 39 years (range 19–66) (Table 1). The prevalence of hr-HPV mRNA was generally similar in physician-collected (34%), sc-WET (37%), and sc-DRY (32%) samples. Most women had 8 or fewer years of education (57%) and reported being divorced or widowed (63%). A higher proportion of women reported using either no contraception (35%) or condoms only (21%) during sexual acts.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic and Sexual Behavioral Characteristics of 399 Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya, 2013 –2018

| Overall (n = 399) | HIV - Positive (n = 193) | HIV - Negative (n = 206) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median or % | N | Median or % | n | Median or % | |

| Characteristic |

||||||

| Age, years (range) | 39 (19–66) | 42 (21–62) | 34 (19–66) | |||

| HPV (physician-collected) | ||||||

| Negative | 262 | 65.7 | 108 | 55.9 | 154 | 74.8 |

| Positive | 137 | 34.3 | 85 | 44.0 | 52 | 25.2 |

| HPV (self-collected, stored wet) | ||||||

| Negative | 252 | 63.2 | 107 | 55.4 | 145 | 70.4 |

| Positive | 147 | 36.8 | 86 | 44.6 | 61 | 29.6 |

| HPV (self-collected, stored dry) | ||||||

| Negative | 272 | 68.2 | 118 | 61.1 | 154 | 74.8 |

| Positive | 127 | 31.8 | 75 | 38.9 | 52 | 25.2 |

| Cervical cytology* | ||||||

| Normal | 284 | 73.4 | 128 | 69.2 | 156 | 77.2 |

| ASCUS | 56 | 14.5 | 26 | 14.1 | 30 | 14.9 |

| LSIL | 20 | 5.2 | 12 | 6.5 | 8 | 4.0 |

| ≥ HSIL | 27 | 6.9 | 19 | 10.3 | 8 | 4.0 |

| Sexually transmitted infections† | ||||||

| Chlamydia | 11 | 2.8 | 2 | 1.0 | 9 | 4.4 |

| Gonorrhea | 10 | 2.5 | 4 | 2.1 | 6 | 2.9 |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 17 | 4.3 | 13 | 6.7 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤ 8 years | 228 | 57.1 | 121 | 62.7 | 107 | 51.9 |

| 9 – 12 years | 130 | 32.6 | 59 | 30.6 | 71 | 34.5 |

| ≥13 years | 41 | 10.3 | 13 | 6.7 | 28 | 13.6 |

| Marital status‡ | ||||||

| Never Married | 136 | 34.9 | 48 | 24.7 | 89 | 43.2 |

| Currently Married | 7 | 1.8 | 3 | 1.6 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 247 | 63.3 | 140 | 72.2 | 107 | 51.9 |

| Number of pregnancies (range) | 2 (0 – 10) | 2 (0 – 10) | 2 (0 – 8) | |||

| Number of live births (range) ‡ | 2 (0 – 7) | 2 (0 – 7) | 2 (0 – 7) | |||

| Age at sexual debut, years (range) ‡ | 17 (9–29) | 17 (11–25) | 17 (9 – 29) | |||

| Type of contraception currently used | ||||||

| None | 138 | 34.6 | 78 | 40.4 | 60 | 29.1 |

| Condoms only | 83 | 20.8 | 34 | 17.6 | 49 | 23.8 |

| Oral contraceptive pill | 35 | 8.8 | 15 | 7.8 | 20 | 9.7 |

| Depo Provera | 85 | 21.3 | 43 | 22.3 | 42 | 20.4 |

| IUD/Tubal ligation/Norplant | 58 | 14.5 | 23 | 11.9 | 35 | 17.0 |

| Frequency of vaginal intercourse during the past week (range) ‡ | 2 (0 – 60) | 1 (0 – 30) | 3 (0 – 60) | |||

| Frequency of vaginal intercourse with condom during the past week (range) ‡ | 1 (0 – 56) | 1 (0 – 30) | 2 (0 – 56) | |||

| Number of sexual partners in the last working week (range) ‡ | 1 (0 – 60) | 1 (0–30) | 2 (0 – 60) | |||

| Number of new sexual partners in the last month (range) ‡ | 0 (0 – 40) | 0 (0 – 40) | 1 (0 – 40) | |||

| Charge per transaction (KSh) (range) § | 400 (10 – 10,000) | 275 (10 – 4000) | 500 (10 – 10,000) | |||

| Tobacco use (≥ 1 cigarette per day) § | 68 | 17.0 | 28 | 14.5 | 40 | 19.4 |

| Alcohol use (≥ 1 drink per week) § | 317 | 79.5 | 148 | 76.7 | 169 | 82.0 |

Abbreviations: AHPV - APTIMA hrHPV mRNA; Hologic/ San Diego, CA; ASCUS - Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; KSh - Kenyan Shilling

Numbers do not add up to 399 due to missing cytology or inadequate sample (Overall n = 11; HIV Positive n = 8; HIV Negative n = 4)

Samples for STI testing were collected by the study physician and are laboratory confirmed using APTIMA

Numbers do not add up to 399 due to missing values: marital status (n = 9); number of live births (n = 6); sexual debut (n = 9); frequency of vaginal intercourse (n = 11); frequency of vaginal intercourse with condoms (n = 13); sexual partners in the last week (n = 11); new sexual partners (n = 13)

Collected at enrollment into parent Mombasa Cohort study

For all three individual HPV-mRNA screening test results, the prevalence of hr-HPV mRNA was higher among HIV-positive women compared to HIV-negative (sc-WET: PD 0.15, 95%CI: 0.06–0.24; sc-DRY: PD 0.14, 95% CI: 0.04–0.23; physician: PD 0.19, 95% CI: 0.10–0.28). The prevalence of abnormal cytology (≥ASCUS) was 27% and was also higher among HIV-positive women (31%) than HIV-negative women (23%) (PD: 0.06, 95% CI: 0.01–0.11).

Concordance of hr-HPV mRNA detection between self-collected stored wet (sc-WET) and dry (sc-DRY)

Overall, approximately one-third of women tested positive for hr-HPV mRNA using the self-collected sampling stored wet (n=147, 37%) or stored dry (n=127; 32%). A quarter of women (97/387) were positive for hr-HPV mRNA with both sc-WET and sc-DRY samples; 12% (47/387) were hr-HPV mRNA positive using the sc-WET sample but not the sc-DRY sample; 6.9% (27/387) were positive for hr-HPV mRNA using the sc-DRY but not the sc-WET sample; and 56% (216/387) were negative for hr-HPV mRNA using both the sc-DRY and sc-WET samples (Table 2). Using the McNemar’s test for paired samples, hr-HPV mRNA positivity was higher in sc-WET samples compared sc-DRY (p = 0.02). High risk-HPV mRNA concordance was determined between sc-WET and sc-DRY samples, stratified by cytology diagnosis. Twelve participants did not have cytology diagnoses available and were excluded from the stratification analyses.

Table 2:

HPV mRNA detection agreement of self-collected samples stored wet (sc-WET) and self-collected stored dry (sc-DRY) samples, stratified by cytology diagnosis (n = 387)

| Total sc-WET+ | Total sc-DRY+ | sc-WET + sc-DRY + | sc-WET + sc-DRY − | sc-WET − sc-DRY + | sc-WET − sc-DRY − | Kappa (95% CI) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall |

147 | 127 | 97 | 47 | 27 | 216 | 0.58 (0.49 –0.66) | 0.03 |

| NILM (n = 284) | 90 | 75 | 52 | 38 | 23 | 171 | 0.48 (0.37 –0.59) | 0.07 |

| ASCUS (n = 56) | 23 | 21 | 19 | 4 | 2 | 31 | 0.78 (0.61–0.95) | 0.69 |

| LSIL (n = 20) | 8 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 0.68 (0.35–1.00) | 1.00 |

| HSIL (n = 27) | 23 | 21 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0.51 (0.11–0.92) | 0.62 |

| Missing cytology (n = 11) | 3 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | - | - |

Abbreviations: sc-WET+: Positive for self-collected sample stored wet in preservation media; sc-WET− : Negative for self-collected sample stored dry; sc-DRY+ : Positive for self-collected sample stored dry; sc-DRY− : Negative for self-collected sample stored dry; NILM: negative for intraepithelial lesions and malignancy; ASCUS: atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; LSIL: low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; CI: confidence intervals

Determined using McNemar’s test

Performance of hr-HPV mRNA testing of self-collected stored wet, self-collected stored dry, and physician-collected specimens, and visual inspection with acetic acid for the detection of ≥HSIL

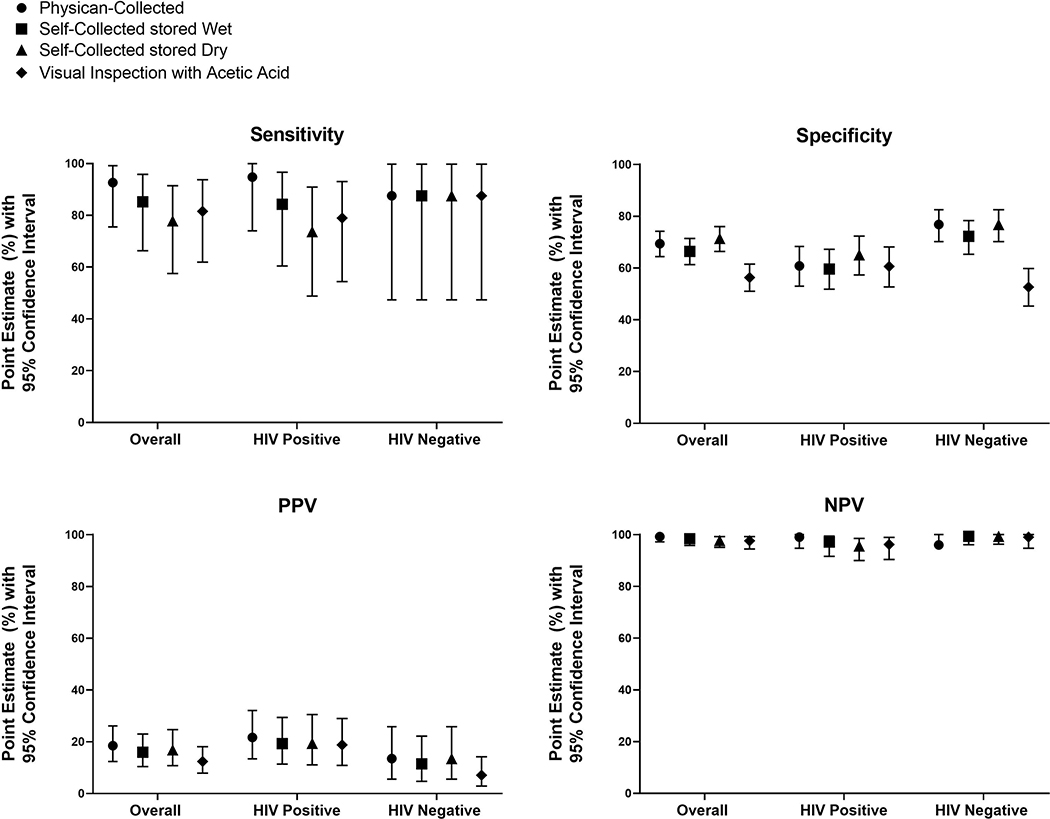

The overall sensitivity estimates of hr-HPV mRNA for ≥HSIL of sc-WET [85% (95% CI: 66–96)] and sc-DRY [78% (95% CI: 58–91)] were comparable (Difference: −0.07, Wald 95% CI: −0.21 to 0.07) (Table 3). Physician-collected samples for hr-HPV mRNA testing showed a similar sensitivity for ≥HSIL detection [93% (95% CI: 76–99] as sc-WET (Difference: −0.07, Wald 95% CI: −0.19 to 0.09) and sc-DRY (Difference: 0.15, Wald 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.32) (Figure 2). Overall, the specificity of hr-HPV mRNA for ≥HSIL detection was similar when comparing sc-WET to physician-collection (Difference: −0.03, 95% CI: −0.08 to 0.01). However, specificity was lower for sc-WET [66% (61–71)] than sc-DRY [71% (66–76)] (Difference: −0.05, 95%CI: −0.10 to −0.00). The specificity of VIA for ≥HSIL was 56% (95% CI: 51–62).

Table 3:

Performance of HPV Testing of Physician-Collected, Wet Self-Collected, and Dry Self-Collected Specimens, and Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) for the detection of cytological high-grade cervical lesions in 387 female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya (2013–2018)

| Overall (n = 387) | HIV Positive (n = 185) | HIV Negative (n = 202) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥HSIL Prevalence | 6.9% (n=27) | 10.3% (n=19) | 4.0% (n=8) | |

| Collection Method | Sensitivity / Specificity for ≥ HSIL | |||

| Physician-Collected | ||||

| Sensitivity of HPV (95% CI) | 93% (76–99) | 95% (74–100) | 88% (47–100) | |

| Specificity of HPV (95% CI) | 69% (64–74) | 61% (53–68) | 77% (70–83) | |

| Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | 19% (12–26) | 22% (13–32) | 14% (6–26) | |

| Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) | 99% (97–100) | 99% (95–100) | 99% (96–100) | |

| Self-Collected stored Wet | ||||

| Sensitivity of HPV (95% CI) | 85% (66–96) | 84% (60–97) | 88% (47–100) | |

| Specificity of HPV (95% CI) | 66% (61–71) | 60% (52–67) | 72% (65–78) | |

| Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | 16% (10–23) | 19% (11–29) | 12% (5–22) | |

| Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) | 98% (96–100) | 97% (92–99) | 99% (96–100) | |

| Self-Collected stored Dry | ||||

| Sensitivity of HPV (95% CI) | 78% (56–91) | 74% (49–91) | 88% (47–100) | |

| Specificity of HPV (95% CI) | 71% (66 – 76) | 65% (57–72) | 77% (70–83) | |

| Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | 17% (11–25) | 19% (11–31) | 14% (6–26) | |

| Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) | 98% (95–99) | 96% (90–99) | 99% (96–100) | |

| VIA | ||||

| Sensitivity of VIA (95% CI) | 82% (62–94) | 79% (54–93) | 88% (47–100) | |

| Specificity of VIA (95% CI) | 56% (51– 62) | 61% (53–68) | 53% (45–60) | |

| Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | 12% (8–18) | 19% (11–29) | 7% (3–14) | |

| Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) | 98% (94–99) | 96% (90–99) | 99% (95–100) | |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence intervals; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; VIA: visual inspection with acetic acid

Figure 2:

Performance of HPV-testing of physician-collected, wet self-collected, and dry self-collected specimens, and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) for the detection of cytological high-grade cervical lesions

The positive predictive value was 16% (95% CI: 10–23) for sc-WET and 17% (95% CI: 11–25) for sc-DRY. The positive predictive value for physician-collection specimens was 19% (95% CI: 12–26). Sensitivity analyses showed that for all three test results, as the prevalence of ≥HSIL increases to 20%, the PPV increases to about 40% and the NPV only decreases slightly (Supplementary Figure 1). The summary of sensitivity analyses is provided in Appendix Table 2.

Acceptability of self-collection methods

Overall, 144 (36%) of women reported preferring self-collection compared to physician-collection (Table 4). Preference for self-collection did not appear to vary by age (<40 years: 39%; ≥40 years: 32%; PD: 0.07, 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.16) or HIV status (HIV-positive: 44%; HIV-negative: 56%; PD: −0.07, 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.03). Women more frequently reported to prefer self-collection stored dry (46%) compared to storage in media (31%). Most women agreed that the Evalyn brush (used for dry storage) was comfortable to insert (88%) and came with instructions easy to understand (95%). About half of participants were concerned that use of the Evalyn brush for self-collection may lead to pain (45%) and about 60% were concerned about properly using the Evalyn brush. Similar patterns were observed for the Viba brush (used for wet storage).

Table 4:

HPV sampling preference of dry and wet HPV mRNA self-collection (n = 399)

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 399) | < 40 years (n = 214) | ≥ 40 years (n = 185) | Prevalence Difference (95% CI) | |

| HPV sample collection method preference | ||||

| Physician-collection | 255 (63.9) | 130 (60.8) | 125 (67.6) | Ref. |

| Self-collection | 144 (36.1) | 84 (39.3) | 60 (32.4) | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.16) |

| Type of self-collection brush preference | ||||

| No preference | 91 (22.8) | 34 (15.9) | 57 (30.8) | Ref. |

| Evalyn brush (self-collection stored dry) | 184 (46.1) | 108 (50.5) | 76 (41.1) | 0.18 (0.08 to 0.29) |

| Viba brush (self-collection stored wet in media) | 124 (31.1) | 72 (58.1) | 52 (28.1) | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.33) |

| Was the Evalyn brush comfortable to insert? | ||||

| Agree | 354 (88.7) | 193 (90.2) | 161 (87.0) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | - |

| Disagree | 44 (11.0) | 21 (9.8) | 23 (12.4) | −0.03 (−0.09 to 0.03) |

| Were the instructions for self-collection using the Evalyn brush easy to understand? | ||||

| Agree | 377 (94.5) | 201 (93.9) | 176 (95.1) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Disagree | 21 (5.3) | 12 (5.6) | 9 (4.9) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.05) |

| Were you concerned about hurting yourself using the Evalyn brush? | ||||

| Agree | 181 (45.4) | 99 (46.3) | 82 (44.3) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Disagree | 218 (54.6) | 115 (53.7) | 103 (55.7) | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.08) |

| Were you concerned about using the Evalyn brush properly? | ||||

| Agree | 236 (59.2) | 133 (62.2) | 103 (55.7) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | - |

| Disagree | 158 (39.6) | 78 (36.5) | 80 (43.2) | −0.06 (−0.16 to 0.03) |

| Was the Viba brush comfortable to insert? | ||||

| Agree | 313 (78.5) | 162 (75.7) | 151 (81.6) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | - |

| Disagree | 84 (21.1) | 51 (23.8) | 33 (17.8) | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.14) |

| Were the instructions for self-collection using the Viba brush easy to understand? | ||||

| Agree | 367 (92.0) | 198 (92.5) | 169 (91.4) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | - |

| Disagree | 31 (7.8) | 16 (7.5) | 15 (8.1) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.05) |

| Were you concerned about hurting yourself using the Viba brush? | ||||

| Agree | 218 (54.6) | 124 (57.9) | 94 (50.8) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.1) | - |

| Disagree | 177 (44.4) | 88 (41.1) | 89 (48.1) | −0.07 (−0.17 to 0.03) |

| Were you concerned about using the Viba brush properly? | ||||

| Agree | 252 (63.2) | 146 (68.2) | 106 (57.3) | Ref. |

| Neither agree or disagree | 9 (2.3) | 5 (2.3) | 4 (2.2) | - |

| Disagree | 138 (34.6) | 63 (29.4) | 75 (40.5) | −0.11 (−0.20 to −0.01) |

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; CI, confidence intervals; Ref, reference

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare hr-HPV mRNA testing on self-collected wet- and dry-stored specimens to detect ≥HSIL. Among 399 FSWs in Kenya, high-risk HPV mRNA testing using self-collected samples stored wet and dry demonstrated similar sensitivity for ≥HSIL detection, although the specificity of dry-stored samples appeared higher. Hr-HPV mRNA positivity was similar in self-collected wet (36%) compared to physician-collected (34%) specimens, but was lower in self-collected dry brushes (32%). Although we found high sensitivity and specificity of hr-HPV mRNA testing using self-collected samples for the detection of ≥HSIL, our cohort of Kenyan FSWs preferred physician-collection of cervical samples over self-collection methods for cervical cancer screening.

Our results demonstrate that compared to wet-stored specimens, dry-stored specimens have similar test characteristics for the detection of high-grade cervical lesions, indicating that dry-stored samples are a viable option for home-based cervical cancer screening programs. Prior studies have directly compared HPV DNA testing using self-collected specimens stored dry and wet and report comparable sensitivities for the detection of CIN 2+(23, 24), and ≥HSIL(25). Sensitivity estimates of HPV DNA testing on dry-stored samples to detect high-grade cervical neoplasia or more severe was similar to our study and ranged from 76% to 90%(23, 24). However, specificity for high-grade cervical neoplasia in prior studies of HPV DNA testing in dry versus wet stored samples was lower for both self-collection methods (46% to 67%) (23, 24).

The prevalence of hr-HPV mRNA based on self-collection specimens in our study was similar to other hr-HPV mRNA studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa among high-risk groups. In a South African study of 325 HIV-infected women, the prevalence of hr-HPV mRNA based on self-collected samples was 43.5%(14), which is similar to the prevalence we found in HIV-positive women (44.6%, sc-WET and 38.9%, sc-DRY). Among a cohort of 344 female sex workers in Nairobi, of which 25% were HIV positive, the prevalence of hr-HPV mRNA was 30%(16). Given that HPV DNA is typically detected at higher prevalence proportions than HPV mRNA within various populations studied(26), our study population has a notably high prevalence of hr-HPV infection.

We observed low positive predictive values (PPV) for HPV testing using sc-WET (16%) and sc-DRY (17%) for the detection of high-grade lesions, although these PPV values are higher than previous self-collection studies conducted in Kenya(8.2%)(16, 17). Here, PPV is an estimate of the proportion of women with a positive HPV mRNA test, who actually have our outcome of interest ≥HSIL. The relatively low PPV is concerning as it may lead to unnecessary treatment when women are offered treatment based on the results of their screening test (i.e. “HPV screen and treat” strategy(2)). However, in areas where women may screen only once in their lifetime, such as Kenya, the low PPV may not be as much of a concern due to a woman’s lifetime risk of hr-HPV infection and persistence. In low-resource settings, the potential benefits of using a screen and treat strategy based on a test with low PPV may outweigh the harms of overtreatment(17), although further evidence is needed.

Among female sex workers in Kenya, we found that physician-collection was more frequently preferred than either self-collection method. These findings are inconsistent with prior studies which found that women generally reported preference of self-collection over physician-collected sampling for cervical cancer screening(27). A recent meta-analysis found that of 12,610 women, 59% (95% CI: 48%−69%) reported preference for self-sampling compared to physician-collection(27). However, there was wide variability across individual studies (22% to 95% of respondents). In our study, women frequently reported feeling concerned about hurting themselves when inserting the self-collection brush into their vaginal canal. They also expressed concerns of their ability to properly carry out self-collection. Our findings are similar to results of a Cameroonian study, which showed that while women found self-collection more comfortable and less embarrassing, a greater proportion preferred physician-collection (62% vs. 29%) as they were concerned about the reliability of results(28). Indeed, factors facilitating uptake of HPV self-collection among women in Kenya include confidence in the ability to complete HPV self-sampling, proximity to screening sites, and feelings of privacy and comfort conducting the HPV self-sampling(29). However, it is important to note that it is unknown whether a woman’s preference for type of collection method would have a meaningful impact on uptake of self-collection when no alternative screening method is provided(30). It is critical that future research addresses barriers to self-collection uptake to better inform the successful implementation of cervical cancer screening programs in low-resource settings.

Our study approach has several advantages. First, this cross-sectional study was nested within an ongoing prospective study with established follow-up procedures, including HIV-positive women—a population at notably high-risk of cervical cancer. Secondly, conventional cervical cytology slides were independently read by 2 cytopathologists to improve the accuracy of cytological diagnoses. Third, screening collection methods were performed sequentially on the same day, allowing for direct comparison of the samples collected. Additionally, we randomized each participant to either first complete self-collection for the dry-or the wet-stored sample to ensure the order of procedures did not affect our results. Finally, our study presents data on the preference of self-collection for cervical cancer screening, which builds on prior work conducted by our group on preferences of 199 FSWs(29) and further underscores the potential obstacles to self-collection in settings with limited access to trained healthcare providers.

Among study limitations, women participating in the Mombasa Cohort volunteer for research visits with regular HIV and STI screening; as such, our findings may not be generalizable to all women eligible for cervical cancer screening in LMICs. Our small sample size also limited our ability to compare the agreement (using the κ statistic) between sc-DRY and sc-WET in women with <HSIL compared with those with ≥HSIL. The interpretation of our analyses is therefore limited due to few HSIL cases, although our results are comparable to prior cervical cancer screening studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa(16). Further research is needed to assess the use of dry-stored specimens with HPV mRNA testing to detect high-grade cervical lesions in large cohorts to confirm our study findings.

In conclusion, based on our findings, the use of dry-stored specimens appears to be a viable option for hr-HPV mRNA testing due to the similar sensitivity and specificity compared to wet-stored self-collected hr-HPV testing for ≥HSIL detection. The possibility of using dry-stored self-collected samples without the need of storage media would improve the utility of self-collection for hr-HPV testing, and could reduce the costs needed for the storage and transport of samples. Limited resources may then be focused on follow-up and treatment services for women who screen positive for hr-HPV, which would be ideal for resource-constrained settings. Additional research to address patient and provider preferences and elimination of barriers to self-collection is crucial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Specimen collection and processing was supported by a grant from Hologic (Boston, MA, USA), and the UNC Gillings Innovation Laboratory through JSS. HPV self-collection kits were donated by Rovers Medical Devices (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). JYI was supported by a NIH NRSA individual predoctoral fellowship (F31-CA210474-01A1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure statements: JSS has received unrestricted educational grants, consultancy, and research grants from Merck Corporation and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) over the past 5 years. RSM has received honoraria for consulting from Lupin Pharmaceuticals and research funding, paid to the University of Washington, from Hologic Corporation. All other authors have no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Guidelines for Screening and Treatment of Precancerous Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Geneva; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):880–91, W312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chidyaonga-Maseko F, Chirwa ML, Muula AS. Underutilization of cervical cancer prevention services in low and middle income countries: a review of contributing factors. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.BruniL B-RL, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report: Kenya. Summary Report 7 October 2016. Barcelona, Spain: ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tota JE, Bentley J, Blake J, et al. Introduction of molecular HPV testing as the primary technology in cervical cancer screening: Acting on evidence to change the current paradigm. Prev Med. 2017;98:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1385–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmeink CE, Bekkers RL, Massuger LF, Melchers WJ. The potential role of self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus detection in cervical cancer screening. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21(3):139–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Cervical, Breast and Prostate Cancers. Kenya: Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation Ministry of Medical Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatla N, Dar L, Patro AR, et al. Can human papillomavirus DNA testing of self-collected vaginal samples compare with physician-collected cervical samples and cytology for cervical cancer screening in developing countries? Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33(6):446–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):172–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamson PC, Huchko MJ, Moss AM, Kinkel HF, Medina-Marino A. Acceptability and Accuracy of Cervical Cancer Screening Using a Self-Collected Tampon for HPV Messenger-RNA Testing among HIV-Infected Women in South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burger EA, Kornor H, Klemp M, Lauvrak V, Kristiansen IS. HPV mRNA tests for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120(3):430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ting J, Mugo N, Kwatampora J, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus messenger RNA testing in physician- and self-collected specimens for cervical lesion detection in high-risk women, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(7):584–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakalembe M, Makanga P, Mubiru F, Swanson M, Martin J, Huchko M. Prevalence, correlates, and predictive value of high-risk human papillomavirus mRNA detection in a community-based cervical cancer screening program in western Uganda. Infect Agent Cancer. 2019;14:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eperon I, Vassilakos P, Navarria I, et al. Randomized comparison of vaginal self-sampling by standard vs. dry swabs for human papillomavirus testing. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin HL Jr., Jackson DJ, Mandaliya K, et al. Preparation for AIDS vaccine evaluation in Mombasa, Kenya: establishment of seronegative cohorts of commercial sex workers and trucking company employees. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10 Suppl 2:S235–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham SM, Holte SE, Peshu NM, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy leads to a rapid decline in cervical and vaginal HIV-1 shedding. AIDS. 2007;21(4):501–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichenheim ME. Confidence intervals for the kappa statistic The Stata Journal. 2004;4(4):421–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez de Gill P, Pham JRT, Nguyen D, Kromrey JD, Kim ES. SAS® Macros CORR_P and TANGO: Interval Estimation for the Difference Between Correlated Proportions in Dependent Samples. SESUG; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jentschke M, Chen K, Arbyn M, et al. Direct comparison of two vaginal self-sampling devices for the detection of human papillomavirus infections. J Clin Virol. 2016;82:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan AM, Sasieni P, Singer A. A prospective double-blind cross-sectional study of the accuracy of the use of dry vaginal tampons for self-sampling of human papillomaviruses. BJOG. 2015;122(3):388–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darlin L, Borgfeldt C, Forslund O, Henic E, Dillner J, Kannisto P. Vaginal self-sampling without preservative for human papillomavirus testing shows good sensitivity. J Clin Virol. 2013;56(1):52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook DA, Smith LW, Law J, et al. Aptima HPV Assay versus Hybrid Capture((R)) 2 HPV test for primary cervical cancer screening in the HPV FOCAL trial. J Clin Virol. 2017;87:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson EJ, Maynard BR, Loux T, Fatla J, Gordon R, Arnold LD. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berner A, Hassel SB, Tebeu PM, et al. Human papillomavirus self-sampling in Cameroon: women’s uncertainties over the reliability of the method are barriers to acceptance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(3):235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oketch SY, Kwena Z, Choi Y, et al. Perspectives of women participating in a cervical cancer screening campaign with community-based HPV self-sampling in rural western Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manguro GO, Masese LN, Mandaliya K, Graham SM, McClelland RS, Smith JS. Preference of specimen collection methods for human papillomavirus detection for cervical cancer screening: a cross-sectional study of high-risk women in Mombasa, Kenya. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.