Abstract

Objective

About 20–26% of children and youth with a mental health disorder (depending on age and respondent) report receiving services from a community-based Child and Youth Mental Health (CYMH) agency. However, because agencies have an upper age limit of 18-years old, youth requiring ongoing mental health services must “transition” to adult-oriented care. General healthcare providers (e.g., family physicians) likely provide this care. The objective of this study was to compare the likelihood of receiving physician-based mental health services after age 18 between youth who had received community-based mental health services and a matched population sample.

Method

A longitudinal matched cohort study was conducted in Ontario, Canada. A CYMH cohort that received mental health care at one of five CYMH agencies, aged 7–14 years at their first visit (N=2,822), was compared to age, sex, region-matched controls (N=8,466).

Results

CYMH youth were twice as likely as the comparison sample to have a physician-based mental health visit (i.e., by a family physician, pediatrician, psychiatrists) after age 18; median time to first visit was 3.3 years. Having a physician mental health visit before age 18 was associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing the outcome than community-based CYMH services alone.

Conclusion

Most youth involved in community-based CYMH agencies will re-access services from physicians as adults. Youth receiving mental health services only within community agencies, and not from physicians, may be less likely to receive physician-based mental health services as adults. Collaboration between CYMH agencies and family physicians may be important for youth who require ongoing care into adulthood.

Keywords: child, adolescent, young adult, mental health services, transition to adult care, adolescent health services, health services

Mots clés: enfant, adolescent, jeune adulte, services de santé mentale, transition aux soins pour adultes, services de santé pour adolescent, services de santé

Résumé

Objectif

Environ 20 à 26 % des enfants et des adolescents souffrant d’un trouble de santé mentale (dépendant de l’âge et du répondant) déclarent recevoir des services d’un organisme communautaire de santé mentale pour enfants et adolescents (SMEA) Toutefois, puisque les organismes ont une limite d’âge supérieur de 18 ans, les jeunes nécessitant des services de santé mentale doivent faire la « transition » aux soins pour adultes. Les prestataires de soins de santé généraux (p. ex., les médecins de famille) dispensent probablement ces services. La présente étude visait à comparer la probabilité de recevoir des services de santé mentale par un médecin après l’âge de 18 ans entre un jeune qui avait reçu des services de santé mentale et un échantillon apparié dans la population.

Méthode

Une étude de cohorte longitudinale appariée a été menée en Ontario, Canada. Une cohorte SMEA qui recevait des soins de santé mentale à l’un des cinq organismes SMEA, âgés entre 7 et 14 ans à leur première visite (N = 2,822), a été comparée pour l’âge, le sexe, les contrôles appariés par région (N = 8,466).

Résultats

Les jeunes des SMEA étaient deux fois plus susceptibles que l’échantillon de comparaison d’avoir une visite de santé mentale par un médecin (c.-à-d. par un pédiatre médecin de famille, des psychiatres) après l’âge de 18 ans le temps moyen avant une première visite était 3,3 ans. Avoir une visite de santé mentale avec un médecin avant l’âge de 18 ans était associé à une plus grande probabilité de connaître le résultat que par les services SMEA communautaires à eux seuls.

Conclusion

La plupart des jeunes impliqués dans les organismes communautaires SMEA accéderont de nouveau aux services de médecins en tant qu’adulte. Les jeunes recevant des services de santé mentale uniquement d’organismes communautaires et non de médecins peuvent être moins susceptibles de recevoir des services de santé mentale par un médecin en tant qu’adultes. La collaboration entre les organismes SMEA et les médecins de famille peut être importante pour les jeunes qui nécessitent des soins constants à l’âge adulte.

Introduction

In Canada, about 18% of youth (aged 12–17 years old) have an identified mental health disorder, and between 43–61% of these youth have some type of contact with mental health services in adolescence (based on youth or parent-report, respectively) (Comeau et al., 2019; Georgiades et al., 2019). Youth and families access mental health services from different providers and across multiple settings or sectors of care (e.g., community agencies, schools, hospitals) (Ford et al., 2007; Leaf et al., 1996; Reid et al., 2011; Tobon et al., 2013). According to a recent population-based survey in Ontario, about 20–26% of children and youth with a mental health disorder (depending on age and respondent) report receiving services from a community-based Child and Youth Mental Health (CYMH) agency (Comeau et al., 2019; Georgiades et al., 2019). CYMH agencies offer a range of specialized mental health services, including assessment and treatment services (e.g., individual or family counselling, day treatment, residential care), for youth and families with varying levels of distress and impairment (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015). Unfortunately, demand for services in CYMH agencies is increasing, particularly for long-term counselling and therapy (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2015). Yet, because CYMH agencies have an upper age limit (typically 18 years old in most jurisdictions), youth requiring ongoing mental health services must eventually “transition” from child to adult-oriented services. Little is known about which youth are likely to re-access mental health services in young adulthood. This information is important for system planning and understanding transitions to adult care among youth involved with CYMH agencies.

Very few studies have examined mental health service utilization during adolescence through to young adulthood, or during the transition period (ages 12–25) (Cappelli et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2010). Some research has examined this among youth treated for severe mental illness [e.g., psychosis, schizophrenia; (Addington & Addington, 2009; Boydell et al., 2013)] and those treated close to the age of transfer [16 to 18 years old, (Cappelli et al., 2014)]. A large proportion (40–60%) of older adolescents with severe mental illness, given their age and disorder severity, are referred to specialized adult mental health services in the community [e.g., mental health centers, substance abuse treatment programs, adult psychiatrists (Addington & Addington, 2009; Cappelli et al., 2014)]. In contrast, for the vast majority of youth involved with community-based agencies in childhood or adolescence, specialized adult mental health services are unlikely to be suitable (or immediately accessible) in young adulthood (Schraeder & Reid, 2017). This may especially be the case for youth with less severe or remitting mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, mild depression), who do not meet eligibility for specialized adult services (Islam et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2010). As a result, general healthcare providers (such as family physician) are likely most accessible for ongoing mental health care for young adults (Schraeder et al., 2020). However, empirical evidence to support the role of family physicians during the transition to adult care, particularly for those leaving community-based CYMH services, is lacking.

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first in Canada to link community-based mental health agency data with provincial health data to examine utilization of physician-based mental health services during the transition period. Our main objective was to describe the use of physician-based mental health services (i.e., mental health-related visit to a family physician or pediatrician, or to a psychiatrist) before and after age 18 years old among a youth cohort who had received community-based CYMH services in Ontario (“CYMH youth”). We also sought to compare the probability of receiving physician-based mental health services in young adulthood between CYMH youth and a matched population comparison sample, and to explore possible predictors of receiving this care. We hypothesized that the CYMH community sample would be more likely than the comparison samples (youth from the general population) to experience the outcome (i.e., a mental health-related physician visit after age 18).

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a longitudinal matched cohort study in the province of Ontario, Canada. Ontario is the most populated province (13.6 million), representing 40% of the country’s population. Our two main data sources were: (1) community CYMH agency data from a Child and Youth Mental Health Dataset (CYMH-D; N = 5,632) obtained in a previous study and held at the University of Western Ontario (Reid et al., 2019); and (2) population health data from datasets held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). The CYMH-D was brought into ICES in order to link youth’s data to population health data records. At the time this study took place, mental health services offered within Ontario CYMH agencies were funded by the Ministry of Child and Youth Services (MCYS; renamed the Ministry of Child, Community and Social Services after provincial election in 2018. Then in April 2019, oversight for all CYMH agencies were transferred to the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care). Healthcare by physicians is funded through the single payer Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP). Eligibility criteria for the CYMH-D and process for data linkage to health data are described below. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Canada, and the research ethics board at Western University (REB#-106553).

Data Sources and Linkage

Community CYMH agency data

The CYMH-D contained administrative data for youth who had received care within any of five Ontario CYMH agencies, serving 5–18 year olds. Participating agencies were accredited by (Children’s Mental Health Ontario, n.d.) and those serving rural and urban populations in Eastern, Central, and Southwestern Ontario were purposively sampled. In a previous study, eligible youth were 5–14 years old at their first in-person CYMH visit (between 2004–2006). Raw data in electronic format were sent to our research team from each agency and included: youth’s date of birth, sex, and visit data [e.g., date, type of contact (e.g., telephone, in-person)]. Only face-to-face visits were included; telephone visits were excluded because it was unclear whether these were for administrative purposes (e.g., rescheduling appointments), or if treatment was provided. Children identified with a developmental disorder (e.g., Autism) at intake, or who were receiving care within an agency program for developmental disorders were excluded; the long-term needs of these youth were not the focus of study.

Population health data

In Ontario, the majority (94%) of physicians’ direct patient care is captured in the OHIP dataset (Rhodes et al., 2006; Steele et al., 2004). ICES holds population-based datasets for the province through a research agreement with Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MHLTC). In accordance with the Personal Health Information Protection Act, datasets (e.g., OHIP) were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.

The Registered Person Database (RPD) is a central database at ICES housing demographic information (e.g., sex, date of birth, postal code) for Ontario residents registered for provincial health insurance coverage. Using probabilistic linkage (Howe, 1998; Jaro, 1995), this database was used to link health datasets to the CYMH-D based on youth’s date of birth, sex, postal code, and initials. Once linked, each individual was given an encoded identifier prior to the creation of this study’s dataset to comply with privacy protocols.

Samples

Child and Youth Mental Health cohort

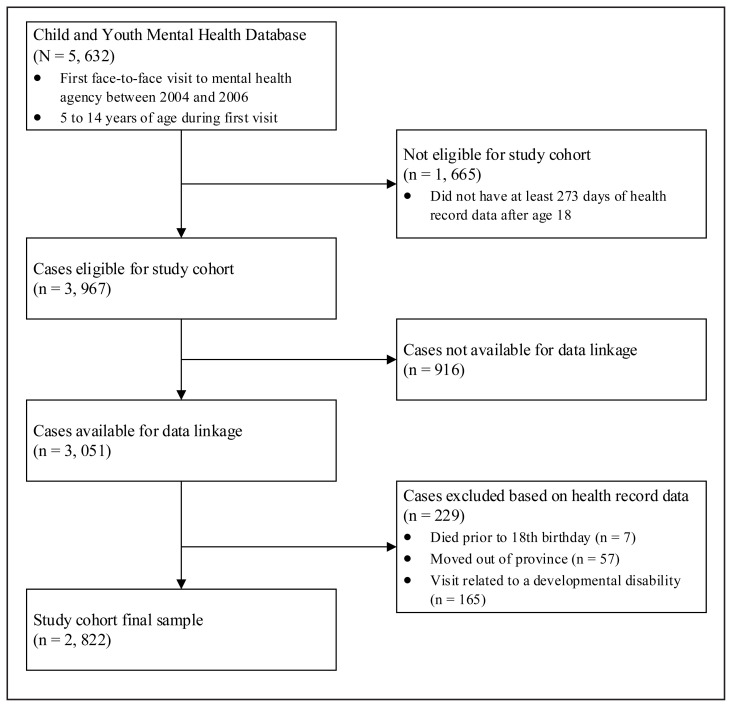

In the CYMH-D (N = 5,632), youth were as young as 4-years old at their first CYMH visit. For the current study, we first selected a subsample of youth who were age 18.75 years old or older (n = 3,967); thus, they had at least 8 months of healthcare data after age 18. Of this subsample, 77% (n = 3,051) were able to be probabilistically linked to the RPD and health datasets at ICES (i.e., had a valid health identifier number). A small percentage (2%) were subsequently excluded (i.e., moved out of province), as were youth (n= 165) who received physician-based services for a developmental disability visit to align with our community sample eligibility criteria. Figure 1 presents a flowchart of eligibility of the final sample (N = 2,822). Seven youth died after age 18 but contributed to analyses (M age at death= 20.2 years, SD= 1.1).

Figure 1.

Participant eligibility flowchart

Non-CYMH sample (matched comparison)

A randomly selected comparison sample was obtained from the RPD, as described above, and matched on sex, year of birth, and Census division (a region of residence; (Statistics Canada, n.d.)) Three controls were selected for every case (Hennessy et al., 1999; Wacholder et al., 1992). Notably, the control sample was not a ‘non-mental health’ sample; although controls did not receive services from a community-based CYMH agency, they may have received physician-based mental health services before age 18. It is very unlikely that youth in our comparison sample would have accessed mental health services from another community-based CYMH agency, since our comparisons were matched by age and residence, and agencies usually provide services for entire counties.

Variables

Demographics

Variables included youth’s sex, urban/rural residence, neighborhood income, and area-level deprivation index (a proxy for socioeconomic status). Residence was determined by linking individuals’ postal codes from the RPD to the 2006 Canadian Census; the 2006 Census was used to align with the year closest to when participants entered the study. Neighborhood income quintiles, based on the province as a whole, were computed using individuals’ Dissemination Areas or rural area (i.e., communities <10,000 people), which are geographical areas with small, relatively stable populations (between 400–700 persons) with similar economic and social conditions. Neighborhood socioeconomic status was based on the Ontario Material Deprivation index (Durbin et al., 2015; To et al., 2013), a census- and geographically-based index derived to show differences in marginalization and understand inequalities in health and social well-being. For each individual, their index score reflected the quintile for the dissemination area in which they resided.

Mental health service use

In-person visits to a CYMH agency were obtained from the CYMH-D; physician-based mental health visits to a physician were obtained from OHIP claims data. Physician-based visits included visits: (i) with a general or mental-health specific service fee code, with a mental health diagnostic code by a family physician or pediatrician, or (ii) to a psychiatrist. Non-physician-based visits (e.g., emergency department, psychiatric hospitalizations) were excluded, as this would not normally be considered part of routine physician-based services in adulthood.

In claims data, diagnostic codes represent the main “reason for the visit” and are coded using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases. These codes are submitted by physicians with “billing codes” (insurance procedures) at each visit. For adult populations, select codes have excellent specificity (97%) and adequate sensitivity (81%) for mental health service use (Steele et al., 2004). Adult-specific codes, however, do not capture all mental health care for youth; childhood diagnoses such as ADHD were not included in previous studies. For this study, two family physicians and a pediatrician independently reviewed all diagnostic and billing codes for their relevance to youth mental health problems; consensus of codes was achieved through group discussion (code list available as Supplementary Materials).

Groups and outcome variable

The main grouping variable was receiving care within a community CYMH agency before age 18 (cases) or not (comparisons). The outcome was first adult physician-based mental health visit (after age 18). Diagnosis and service provided (from claims data) and physician specialty (i.e., family medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry; ICES Physician Database) described this visit.

Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA, n.d.) and completed at ICES by ICES analysts. Time to outcome (i.e., having an adult physician-based mental health visit), was determined using survival analyses.(Hosmer et al., 2008) Time to outcome was computed in days from the origin (18th birthday), coded as Day 0. Comparisons were given an index date (Day 0) that aligned with cases’ first CYMH visit. Survival analysis is designed for time-to-event data where not all participants experience the outcome and participants have variable follow-up durations. Follow-up times varied in the CYMH sample due to variable entry times into the study (i.e., first CYMH visit). Data were used up to the outcome, or to the point of censoring (lost to follow-up), whichever occurred first.(Cleves et al., 2010; Hosmer et al., 2008)

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate survival curves based on life-table estimates (e.g., probability of experiencing the outcome per day), and to test the proportional hazards assumption. The main grouping variable was entered into three Cox regression models. First, a crude model derived a hazard ratio (HR), comparing the likelihood of the outcome between cases and comparisons. Second, in an adjusted model, the effect of community-based CYMH services on the outcome was assessed after adjusting for the potential added effect of a covariate (i.e., receiving physician-based mental health services between start of agency involvement and before age 18). Finally, a stratified Cox model visually described the effect of the covariate on the outcome over time, between cases and comparisons. Descriptive statistics for four groups, from this stratification, are provided. Because the stratified model assumes no interaction between the grouping variable and covariate, an interaction model was tested. An alpha level of p< .05 was used to test for statistical significance.

Results

Descriptive Findings

The CYMH sample consisted of 2,822 youth and a matched non-CYMH comparison sample consisted of 8,466 youth. The majority (60%) of the CYMH sample were male and on average 11.2 years old at their first CYMH visit (SD= 1.70; Range= 7–14 years). Most youth (84%) resided in urban communities and lived in neighborhoods that were evenly distributed across deprivation quintiles. The average length of follow-up, from age 18, was 3.9 years; with a maximum of up to 8 years (or age 26). From the CYMH sample, 70% (n = 2,088) had prior physician involvement, defined as at least one physician-based mental health visit between the start of their CYMH agency involvement to <18 years old (55%, 17%, 27% visited a family physician, pediatrician, or psychiatrist, respectively); thus, 30% did not. In the comparison sample, 34% (n = 2,895) had at least one physician-based mental health visit (70%, 17%, 14% visited a family physician, pediatrician, or psychiatrist, respectively). Table 1 summarizes descriptive characteristics for the four groups that resulted from our stratified Cox model, as described in the methods. Notably, in the CYMH sample, youth who also visited a physician for mental health care before age 18 had a higher total number of CYMH visits (Median = 8) compared to those without physician involvement (Median = 4).

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics between four cohort groups based on Cox stratified model

| Characteristics | Community CYMH + physician-based mental health a (n = 2088) n (%) |

Community CYMH only (n = 734) n (%) |

Physician-based mental health only (n = 2895) n (%) |

No mental health (n= 5571) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start of study window | M = 11.11 (SD = 1.76) | M = 11.50 (SD = 1.65) | M = 11.0 (SD = 1.80) | M = 11.4 (SD = 1.75) |

| Sex (% female) | 826 (39.6%) | 1,164 (40.2%) | 313 (42.6%) | 2,253 (40.4%) |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 327 (15.7%) | 471 (16.3%) | 137 (18.7%) | 4,600 (16.6%) |

| Urban | 1,757 (84.1%) | 2,471 (83.5%) | 595 (81.1%) | 925 (82.6%) |

| Neighborhood income quintile | ||||

| Missing | * | * | 9 (0.3%) | 60 (1.1%) |

| Q1 (lowest) | 446 (21.4%) | 155 (21.1%) | 544 (18.8%) | 977 (17.5%) |

| Q2 | 488 (23.4%) | 162 (22.1%) | 614 (21.2%) | 1,109 (19.9%) |

| Q3 | 467 (22.4%) | 145 (19.8%) | 657 (22.7%) | 1,292 (23.2%) |

| Q4 | 396 (19.0%) | 160 (21.8%) | 609 (21.0%) | 1,236 (22.2%) |

| Q5 (highest)** | 285–287** (13.6–13.7%) | 108–110** (14.7–14.9%) | 462 (16.0%) | 897 (16.1%) |

| Ontario Marginalization index b | ||||

| Missing | 20 (1.0%) | 8 (1.1%) | 36 (1.2%) | 117 (2.1%) |

| Q1 (least deprived) | 383 (18.3%) | 153 (20.8%) | 588 (20.3%) | 1,235 (22.2%) |

| Q2 | 454 (21.7%) | 187 (25.5%) | 665 (23.0%) | 1,383 (24.8%) |

| Q3 | 462 (22.1%) | 152 (20.7%) | 621 (21.5%) | 1,225 (22.0%) |

| Q4 | 357 (17.1%) | 110 (15.0%) | 473 (16.3%) | 775 (13.9%) |

| Q5 (most deprived) | 412 (19.7%) | 124 (16.9%) | 512 (17.7%) | 836 (15.0%) |

| Total CYMH Visits (IQR) | ||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 8 (2–21) | 4 (1–9) | NA | NA |

| Duration of CYMH involvement in months (IQR) | 6.97 (0.87–24.13) | 2.12 (0.03–9.53) | NA | NA |

| Duration between last CYMH visit and age 18 in years (IQR) | 5.75 (4.34, 7.47) | 5.8 (4.52–7.53) | 6 (4.54–7.73) | 5.64 (4.24–7.22) |

Note. NA = Not applicable. CYMH = Child and Youth Mental Health. IQR = Interquartile range; Median (Q1,Q3).

Physician-based mental health refers to mental health visit to a physician (e.g., family physician, pediatrician, psychiatrist) based on Ontario Health Insurance Plan physician claims data.

- individuals aged 20 years and over without a high school graduation;

- lone parent families;

- individuals receiving government transfer payments;

- individuals 15 years old and over who are unemployed;

- individuals living below the low-income cut-off (defined by Statistics Canada and adjusted for family and community size); and

- households living in dwellings in need of major repair. Q = quintile.

Cell sizes suppressed due to n < 5.

Ranges provided to ensure suppressed cells cannot be re-calculated, in accordance with ICES reporting guidelines.

Time to Outcome (First Physician-based Mental Health Visit After Age 18)

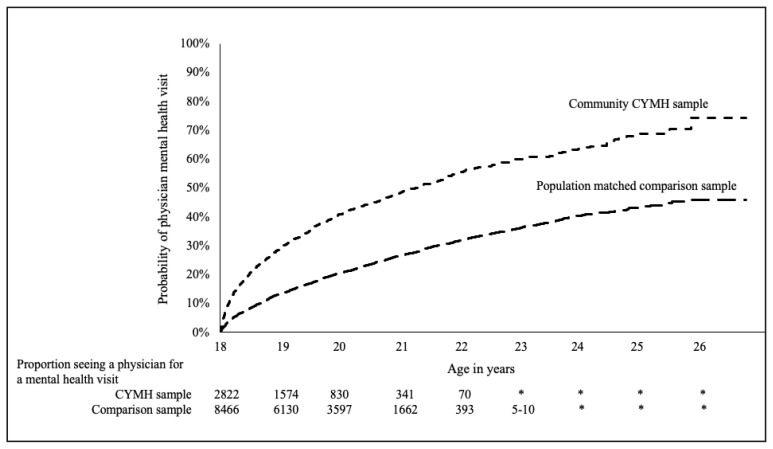

As depicted in Figure 2, Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the probability of having a physician-based mental health visit after age 18 for the CYMH and comparison samples. The crude Cox model revealed the CYMH sample was twice as likely as comparisons to have a physician-based mental health visit (HR= 2.09; 95% CI= 1.95–2.22; p <.0001). Based on life-table analyses, 25% of the CYMH sample had a physician-based mental health visit within 10 months after their 18th birthdate, and 50% did so by 40.5 months.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan-Meier curves show the probability of having an physician-based mental health visit (i.e., mental health visit by a family physician, pediatrician or psychiatrist) as a function of time since a youth’s 18th birthday (presented as age in years) for CYMH cohort vs. comparisons. The number of youth followed up for each time interval (number at risk) is shown underneath the x-axis. CYMH refers to Child and Youth Mental Health Services. *Cell sizes suppressed due to n < 5.

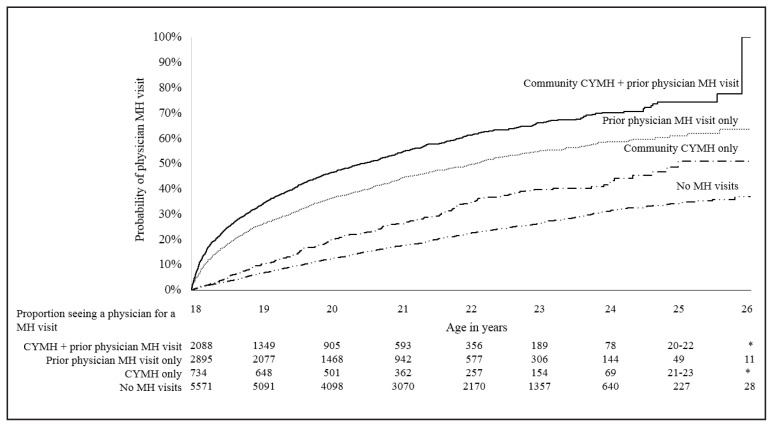

A stratified Cox model (presented in Figure 3) showed the effect of community-based CYMH services stratified by youth’s prior physician involvement (i.e., between start of CYMH agency involvement and <18 years old). The effect of group (i.e., community-based CYMH services as a youth, or not) remained significant after adjusting for also having physician-based mental health visit before age 18, but the adjusted HR was lower than in the crude model (HRadjusted =1.43; 95% CI= 1.34–1.54; p <.0001). In the adjusted model, after accounting for group, the probability of having a physician-based mental health visit after age 18 was 2.77 times higher among youth with prior physician involvement than those without (HRadjusted =2.77, 95% CI=2.58–2.97; p <.0001). The effect of prior physician involvement was the same for cases and comparisons (i.e., no interaction), indicated by the similar distance between survival curves. In other words, prior physician involvement made it more likely to have a physician-based mental health visit after age 18 for both groups. Figure 3 shows that youth who received community-based CYMH services and prior physician involvement were most likely to have a physician-based mental health visit as adults. Comparisons (non-CYMH youth) without prior physician involvement were least likely to have a physician-based mental health visit as adults.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier curves show the probability of having an physician-based mental health visit (i.e., mental health visit by a family physician, pediatrician or psychiatrist) as a function of time since a youth’s 18th birthday (presented as age in years) for the four groups from the stratified Cox model. The number of youth followed up for each time interval (number at risk) is shown underneath the x-axis. CYMH refers to Child and Youth Mental Health Services. *Cell sizes suppressed due to n < 5.

Table 2 summarizes descriptive information related to the first physician-based mental health visit in young adulthood. Of those with a visit (n = 3,985; total youth across all four groups), 85% were seen by a family physician; the rest were seen by a psychiatrist (11.8%) or pediatrician (2.8%). Across groups, youth were most likely to be seen by a family physician; youth with prior physician-based mental health services were more likely to be seen by a psychiatrist after age 18 than those who had not. The most common diagnostic code across all physician visits was anxiety (>50% across groups).

Table 2.

Comparing visit characteristics for youth who had one or more physician mental health visits after age 18

| Characteristics | Community CYMH + physician-based mental health (n= 2,088) | Community CYMH only (n= 734) | Physician-based mental health only (n= 2,895) | No mental health (n= 5,571) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one physician-based mental health visit after age 18 (% of total individuals in sub-group) | n = 1197 (57.3%) | n = 239 (32.6%) | n = 1323 (45.7%) | n = 1226 (22.0%) |

| Median survival time (when 50% experienced outcome) after age 18 | 29 months | 84 months | 49 months | † |

| Type of provider first physician-based mental health visit after age 18 | ||||

| Family physician | 76.70% | 91.60% | 82.80% | 94.70% |

| Psychiatrist | 8.80% | 6.3–7.9%** | 13.10% | 4.9–5.2%** |

| Pediatrician | 4.70% | * | 3.70% | * |

| Diagnostic code at first physician-based mental health visit after age 18 a | ||||

| Anxiety disorders | 52.50% | 64.80% | 55.30% | 64.60% |

| Depression | 11.70% | 8.80% | 12.10% | 9.30% |

| Hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood (commonly ADHD) | 7.00% | * | 6.20% | 1.80% |

| Behavior disorders | 5.40% | * | 4.70% | * |

| Drug dependence | 3.60% | 5.00% | 2.40% | * |

| Other childhood mental health disorders (e.g., habit spasms, tics) | 3.10% | 7.50% | 4.70% | 6.50% |

Note. CYMH = Child and Youth Mental Health. ADHD = Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder. Physician-based mental health visit based on Ontario Health Insurance Plan physician claims data.

Survival is greater than 50% at median survival time.

Not all diagnostic codes provided; thus percentages do not equate to 100%.

Cell sizes suppressed due to n < 5.

Ranges provided to ensure suppressed cells cannot be re-calculated, in accordance with ICES reporting guidelines.

Discussion

This study compared the probability of receiving physician-based mental health services in young adulthood between an Ontario-based sample of youth involved with CYMH community agencies, and a demographically matched population-based sample. Youth involved with community-based CYMH agencies were mostly male (60%), which likely reflects an over-representation of boys with externalizing disorders in treatment (Reid et al., 2019). CYMH youth were twice as likely as comparisons to receive physician-based mental health services as young adults (ages 18–26). Our findings also revealed the majority of CYMH youth (70%) received some mental health care by physicians before young adulthood, most commonly by family physicians. These youth had a higher total number of CYMH visits and longer duration of involvement at CYMH agencies than youth who had CYMH involvement but had not visited a physician for mental health care prior to age 18. In the comparison sample, 34% received physician-based mental health services before age 18, comparable to other population-based studies in Ontario (MHASEF Research Team, 2015). Interestingly, in both samples, receiving physician-based mental health services before age 18 was significantly associated with the outcome re-accessing mental health services in young adulthood. Youth involved with CYMH agencies alone, without physician involvement, were less likely to re-access mental health services in young adulthood than those with both physician and community CYMH agency involvement.

These findings are important for two key reasons. First, they provide evidence that childhood-onset mental health problems can be long-lasting, even with “early” intervention (i.e., during childhood or adolescence). We found that receiving care in a CYMH agency, or by a physician, was strongly related to receiving mental health care in young adulthood. Previous treatment follow-up studies, which follow youth 1–5 years post-treatment, have reported high rates of recurrence and persistence for children’s mental health problems [e.g., depression, anxiety, ADHD, etc. (Curry et al., 2011; Greene et al., 1997; Manassis et al., 2004; Nevo & Manassis, 2009; Sim et al., 2004; Vitiello et al., 2011)]. A major strength of our study was our long follow-up period - 6.5 to 12 years post-CYMH services - spanning adolescence and young adulthood. The possibility of needing ongoing care into adulthood is recognized by many youth and families who receive CYMH care (Schraeder et al., 2018), but typically not recognized by the systems that care for them. We therefore must pay closer attention to post-treatment periods, particularly as youth approach the arbitrary “age of transfer” (i.e., 18 years old), since many may require ongoing care beyond the children’s mental health system.

Second, our study provides further evidence of fragmentation within Canada’s mental health “system” (Mcgihon et al., 2018; Stewart & Hirdes, 2015; Yung, 2016). By linking community CYMH agency data and health record data (i.e., physician claims), we found that 26% (n= 734) of the CYMH sample were only seen within a CYMH agency, and never by a physician for mental health problems, before reaching adulthood. This group was significantly less likely to receive physician-based mental health care as adults (33% of this group received this care) compared to youth who received physician-based mental health care before age 18 (57% of this group received physician care). Some CYMH youth may not have needed, or declined, mental health services offered to them in adulthood; this cannot be determined from our data. Receiving mental health care by a CYMH agency and a physician (most likely a family physician) likely provides an opportunity for treated youth to also become connected to the healthcare system, in case problems recur during young adulthood. There are recent initiatives in Canada (ACCESS-Open Minds), similar to Australia’s headspace programs (Rickwood et al., 2014) that aim to help communities enhance the systems that care for older children, youth, and young adults with mental health problems, including co-location of family physicians and specialized mental health clinicians (Abba-Aji et al., 2019; Malla et al., 2019). Further research is needed to understand whether these models can be effectively scaled up to address all youth who may require ongoing care into adulthood, given that the population prevalence of mental health contact with CYMH agencies is 5.9% (Reid et al., manuscript under review).

The Role of Family Physicians for Youth “Transitioning” to Adult Care

Family physicians are the first professional that most parents turn to with concerns related to their child’s mental health (Brugman et al., 2001; Rushton et al., 2002; Sayal, 2006) and many refer youth and families to community services for help. However, the role of family physicians post-treatment, or after families have engaged with community-based mental health services, is poorly understood (Bhawra et al., 2016; Schraeder et al., 2017). This was first noted by the authors of the “TRACK” study in the United Kingdom (Singh et al., 2010) which followed a youth cohort (N=154) treated by publicly-funded mental health services in childhood and adolescence. In this cohort, 85% of youth were considered to need ongoing mental health care in adulthood by their youth mental health provider; yet, only 49% “transferred” to adult mental health services [e.g., to inpatient psychiatric services, adult psychiatrists, etc. (Paul et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2010)]. A secondary analysis of these data revealed 53% of those who failed to transfer (e.g., not eligible) were discharged to their family physician as young adults (Islam et al., 2016). Similarly, in our study, most young adults were first seen first by a family physician (mainly for issues related to anxiety or depression); a very small percentage were first seen by a psychiatrist after the age of transfer. If family physicians will become responsible for caring for most CYMH treated youth in adulthood, then we must carefully consider and support the role they will take on in manging transitions and mental health care over the lifespan, including during and after CYMH treatment (McGorry, 2007; Patel et al., 2007; Schraeder et al., 2020).

Considerations for Future Research

This study is the first longitudinal matched cohort study to examine mental health service utilization across community CYMH agencies and Canada’s healthcare system. Our cross-sectoral approach to understanding mental health service utilization was a major strength of this study. Our methods, and findings, highlight a need for better system integration across community and healthcare sectors which provide youth mental health services (Boyle et al., 2019).

This study is not without limitations. First, we were not able to compare our cohort to those who were excluded (n = 961; invalid health identifier) on any health-related variables as these youth could not be linked to health records. Secondly, of the 49% (n= 5,571) of youth in our cohort who did not receive mental health care by a physician or community agency (before age 18), it is possible they may have accessed mental health services from other sectors (e.g., school, urgent care clinics). Youth could have accessed mental health services privately (e.g., private psychologist); however, a small percentage of the population with mental health problems access care privately (Duncan et al., 2019). Some youth might also have received care from another healthcare provider (e.g., social worker, nurse); in Canada, services provided by non-physician healthcare professionals are not available in population health datasets. Billed mental health services in Ontario, delivered by physicians, is therefore an underestimate of all mental health services available to the population. Further, with respect to physician billing, we noted a low incidence of behavior disorder diagnoses in adulthood, which may be an artifact of a lack of codes to capture these problems (e.g., no codes exist for adult ADHD). Only about 17% of our cohort were old enough to have follow-up data beyond age 24, which may have limited our ability to accurately capture service utilization during this period.

The proportion of youth in need of adult mental health care could not be determined in our study. It was not possible with our data to know if not having a mental health visit reflected poor access to adult care (e.g., youth not able to access their family physician), symptom improvement, or remission. Similarly, for youth in our cohort who received physician-based mental health services in young adulthood, it was not possible to know if this care was appropriate and/or matched their level of need. After age 18, rates of successful “transition” could therefore not be reported as there was not a clear denominator of who required adult mental health care. Criteria to identify individuals with long-term mental health needs is in its infancy (Purcell et al., 2015; Schraeder & Reid, 2017). As recommended by others (Barwick et al., 2004; Boyle et al., 2019), implementation of standardized measures to routinely collect outcome data at CYMH agencies, which could be linked to population-level healthcare records, would be a worthwhile investment in order to understand whether youths’ involvement with other healthcare services (e.g., by physicians) is needed based on their measured need for mental health care post-treatment.

Finally, our survival analyses focused on prior mental health involvement during childhood and adolescence as the only predictor of future service utilization in young adulthood. Examining additional predictors (e.g., geographical accessibility to primary care or other mental health services; socio-economic characteristics of young adults) is a goal of our future work and needed to inform practice and policy recommendations. For example, identifying factors associated with increased use of mental health care by young adults could inform the development of preferred and effective transition services.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the staff at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), Toronto, ON for their assistance with the data analyses; in particular, Cindy Lau. The assistance of Saadia Hameed, Michael Craig, and S. Tariq Ahmed with the review of the OHIP coding, and Alberto Nettel-Aguirre with the analyses, was greatly appreciated. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. This project was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant (#137048). G. Reid was supported by the Children’s Health Research Institute, London ON. K. E. Schraeder was supported by a Transdisciplinary Understanding and Training on Research – Primary Health Care (TUTOR-PHC) Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Children’s Health and Research Institute. G.J. Reid was supported by the Children’s Health Foundation. The authors have no other financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Abbreviations

- CYMH

Child and Youth Mental Health

- OHIP

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- MCYS

Ministry of Child and Youth Services

- MD

Material Deprivation (Ontario Marginalization Index)

- RPDB

Registered Persons Database

- MHLTC

Ministry of Health and Long Term Care

- ICES

Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

This project was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR #137048: “Before, during, and after: Service use in the mental health and health sectors within Ontario for children and youth with mental health problems). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Presentation information

K. Schraeder completed this study as part of her doctoral dissertation (Clinical Psychology) at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. Her dissertation has been published in the university’s electronic thesis repository. This study was presented as a poster at the International Population Data Linkage Network Conference, Banff, Alberta, Canada: September 12–14, 2018.

References

- Abba-Aji A, Hay K, Kelland J, Mummery C, Urichuk L, Gerdes C, …Shah JL. Transforming youth mental health services in a large urban centre: ACCESS Open Minds Edmonton. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2019;13(Suppl 1):14–19. doi: 10.1111/eip.12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Addington D. Three-year outcome of treatment in an early psychosis program. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):626–630. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barwick M, Boydell KM, Cunningham CE, Ferguson HB. Overview of Ontario’s screening and outcome measurement initiative in children’s mental health. The Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review. 2004;4(13):105–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhawra J, Toulany A, Cohen E, Hepburn CM, Guttmann A. Primary care interventions to improve transition of youth with chronic health conditions from paediatric to adult healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell KM, Volpe T, Gladstone BM, Stasiulis E, Addington J. Youth at ultra high risk for psychosis: Using the Revised Network Episode Model to examine pathways to mental health care. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2013;7(2):170–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Duncan L, Georgiades K, Comeau J, Reid GJ, O’Briain W, …Waddell C. Tracking Children’s Mental Health in the 21st Century: Lessons from the 2014 OCHS. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;64(4):232–236. doi: 10.1177/0706743719830025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugman E, Reijneveld SA, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Identification and management of psychosocial problems by preventive child health care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:462–469. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.462. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0035072078&partnerID=40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Care for Children and Youth with Mental Disorders in Canada. 2015;19(1) doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli M, Davidson S, Racek J, Leon S, Vloet M, Tataryn K, Lowe J. Transitioning Youth into Adult Mental Health and Addiction Services: An Outcomes Evaluation of the Youth Transition Project. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research C. 2014:597–610. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Mental Health Ontario. About CMHO. n.d. [Accessed August 2020]. Https://Cmho.Org/

- Children’s Mental Health Ontario. Children’s Mental Health Ontario (CMHO) n.d. https://www.cmho.org/

- Cleves M, Gould W, Gutierrez R, Marchenko Y. An Introduction to Survival Analysis Using Stata. Third Edition. Stata Press; 2010. http://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Survival-Analysis-Using-Edition/dp/1597180742. [Google Scholar]

- Comeau J, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Boyle MH. Changes in the Prevalence of Child and Youth Mental Disorders and Perceived Need for Professional Help between 1983 and 2014: Evidence from the Ontario Child Health Study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;64(4):256–264. doi: 10.1177/0706743719830035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, Ginsburg G, Kratochvil C. Recovery and recurrence following treatment for adolescent major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):263–270. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L, Georgiades K, Birch S, Comeau J, Wang L, Boyle MH. Children’s Mental Health Need and Expenditures in Ontario: Findings from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;64(4):275–284. doi: 10.1177/0706743719830036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin A, Moineddin R, Lin E, Steele LS, Glazier RH. Examining the relationship between neighbourhood deprivation and mental health service use of immigrants in Ontario, Canada: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006690. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford T, Hamilton H, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Child Mental Health is everybody’s business: The prevalence of contact with public sector services by type of disorder among British school children in a three-year period. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;12(1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Comeau J, Boyle MH. Six-Month Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Service Contacts among Children and Youth in Ontario: Evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;64(4):246–255. doi: 10.1177/0706743719830024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Sienna M, Garcia-Jetton J. Adolescent outcome of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social disability: Results from a 4-year longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(5):758–767. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.758. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9337495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Factors Influencing the Optimal Control-to-Case Ratio in Matched Case-Control Studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(2):195–197. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Survival. 6. Vol. 14. Wiley; 2008. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GR. Use of computerized record linkage in cohort studies. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1998;20(1):112–121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z, Ford T, Kramer T, Paul M, Parsons H, Harley K, …Singh SP. Mind how you cross the gap! Outcomes for young people who failed to make the transition from child to adult services: the TRACK study. BJPsych Bulletin. 2016;40(3):142–148. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.115.050690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaro MA. Probabilistic linkage of large public-health data files. Statistics In Medicine. 1995;14(5–7):491–498. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf P, Alegria M, Cohen P, Goodman S, McCue Horwitz S, Hoven C, …Regier D. Mental Health Service Use in the Community and Schools: Results from the Four-Community MECA Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:889–897. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla A, Iyer S, Shah J, Joober R, Boksa P, Lal S, …Vallianatos H. Canadian response to need for transformation of youth mental health services: ACCESS Open Minds (Esprits ouverts) Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):697–706. doi: 10.1111/eip.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K, Avery D, Butalia S, Mendlowitz S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with childhood anxiety disorders: functioning in adolescence. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;19(4):209–216. doi: 10.1002/da.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgihon R, Hawke LD, Chaim G, Henderson J. Cross-sectoral integration in youth-focused health and social services in Canada: A social network analysis. 2018;1:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3742-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P. The specialist youth mental health model: Strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health system. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;187(7):53–56. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01338.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17908028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHASEF Research Team. The mental health of children and youth in Ontario: A baseline scorecard. 2015. [Date Accessed: August 2020]. Https://Www.Ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2015/Mental-Health-of-Children-and-Youth https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2015/Mental-Health-of-Children-and-Youth.

- Nevo GA, Manassis K. Outcomes for treated anxious children: A critical review of Long-Term-Follow-Up studies. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(7):650–660. doi: 10.1002/da.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Ford T, Kramer T, Islam Z, Harley K, Singh SP. Transfers and transitions between child and adult mental health services. The British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 2013;54:s36–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell R, Jorm AF, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Amminger GP, …Mcgorry PD. Transitions Study of Predictors of illness progression in young people with mental ill Health: Study methodology. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2015;9(1):38–47. doi: 10.1111/eip.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GJ, Bennett K, Bennett T, Boyle M, Butt M, Duncan L, Waddell C. Predictors and patterns of accessing health and mental health services in a community-based sample of children and youth. n.d Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Reid GJ, Cunningham CE, Tobon JI, Evans B, Stewart M, Brown JB, …Shanley DC. Help-seeking for children with mental health problems: Parents’ efforts and experiences. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011;38(5):384–397. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GJ, Stewart SL, Barwick M, Carter J, Leschied A, Neufeld RWJ, …Zaric GS. Predicting patterns of service utilization within children’s mental health agencies. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes AE, Bethell J, Schultz SE. ICES Atlas: Primary Care in Ontario. Intsitute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. Primary Mental Health Care; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood DJ, Telford NR, Parker AG, Tanti CJ, McGorry PD. Headspace - Australia’s innovation in youth mental health: Who are the clients and why are they presenting? Medical Journal of Australia. 2014;200(2):108–111. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton J, Bruckman D, Kelleher K. Primary care referral of children with psychosocial problems. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(6):592–598. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.592. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. Cary, North Carolina, USA. n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K. Annotation: Pathways to care for children with mental health problems. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2006;47(7):649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01543.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16790000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraeder K, Brown JB, Reid GJ. Perspectives on Monitoring Youth with Ongoing Mental Health Problems in Primary Health Care: Family Physicians Are “Out of the Loop”. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2017;45(2):219–236. doi: 10.1007/s11414-017-9577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraeder K, Dimitropolos G, Mcbrien K, Li J (Yijia), Samuel S. Perspectives from primary health care providers on their roles for supporting adolescents and young adults transitioning from pediatric services. BMC Family Practice. 2020;21(140):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01189-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraeder K, Reid GJ. Who Should Transition? Defining a Target Population of Youth with Depression and Anxiety That Will Require Adult Mental Health Care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2017;44(2):316–330. doi: 10.1007/s11414-015-9495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraeder K, Reid GJ, Brown JB. “I Think He Will Have It Throughout His Whole Life”: Parent and Youth Perspectives About Childhood Mental Health Problems. Qualitative Health Research. 2018;28(4):548–560. doi: 10.1177/1049732317739840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim MG, Hulse G, Khong E. When the child with ADHD grows up. Australian Family Physician. 2004;33(8):615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Paul M, Ford T, Kramer T, Weaver T, McLaren S, …White S. Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: Multiperspective study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):305–312. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Census tract reference maps, by census metropolitan areas or census agglomerations. n.d. 2011. [Accessed August 2020]. Http://Www12.Statcan.Gc.ca/Census-Recen.

- Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, Evans M. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Medical Care. 2004;42(10):960–965. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, Hirdes JP. Identifying mental health symptoms in children and youth in residential and in-patient care settings. Healthcare Management Forum. 2015;28(4):150–156. doi: 10.1177/0840470415581240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To T, Stanojevic S, Feldman R, Moineddin R, Atenafu EG, Guan J, Gershon AS. Is asthma a vanishing disease? A study to forecast the burden of asthma in 2022. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobon JI, Reid GJ, Goffin RD. Continuity of Care in Children’s Mental Health: Development of a Measure. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2013:668–686. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Keller M, …Brent D. Long-term outcome of adolescent depression initially resistant to SSRI treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):388–396. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05885blu.Long-Term. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacholder S, Silverman DT, McLaughlin JK, Mandel JS. Selection of controls in case-control studies. III Design options. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;135(9):1042–1050. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR. Youth services: The need to integrate mental health, physical health, and social care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;51(1):327–329. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]