Abstract

Background/purpose

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has emerged as a highly contagious and lethal virus, devastating healthcare systems throughout the world. Following a period of stability, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic appears to be re-intensifying globally. As the virus continues to evolve, so does our understanding of its implications on ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). We sought to describe a single center STEMI experience at one of the epicenters during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods/materials

We conducted a retrospective, observational study comparing STEMI patients during the pandemic period (March 1 to August 31, 2020) to those with STEMI during the pre-pandemic period (March 1 to August 31, 2019) at NYU Langone Hospital – Long Island, a tertiary-care center in Nassau County, New York. Additionally, we describe our subset of COVID-19 patients with STEMI during the pandemic.

Results

The acute myocardial infarction (AMI) team was activated for 183 patients during both periods. There were a similar number of AMI team activations during the pandemic period (n = 93) compared to the pre-pandemic period (n = 90). Baseline characteristics did not differ during both periods; however, infection control measures and additional investigation were required to clarify the diagnosis during the pandemic, resulting in a signal toward longer door-to-balloon times (95.9 min vs. 74.4 min, p = 0.0587). We observed similar inpatient length of stay (LOS) (3.6 days vs. 5.0 days, p = 0.0901) and mortality (13.2% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.5876). There were 6 COVID-19-positive patients who presented with STEMI, of whom 4 were emergently taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory with successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) performed in 3 patients. The 2 patients who were not offered primary PCI expired, as both were treated medically, one with thrombolytics.

Conclusions

Our single-center study, in New York, at one of the epicenters of the pandemic, demonstrated a similar number of AMI team activations, mimicking the seasonal variability seen in 2019, but with a signal toward longer door-to-balloon time. Despite this, inpatient LOS and mortality remained similar.

Keywords: COVID-19, STEMI

1. Introduction

From its earliest days in November 2019, to the declaration of a pandemic in March 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has emerged as a highly contagious and lethal virus, devastating healthcare systems throughout the world [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. SARS-CoV-2 is the etiological agent for the catastrophic respiratory illness known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has infected over 90 million people worldwide [4]. Patients with underlying cardiovascular disease appear to have more severe disease and, thus, worse outcomes [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. Furthermore, COVID-19 has demonstrated deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system in patients with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular involvement has been shown to be a negative prognostic factor in these patients [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Furthermore, the pandemic appeared to decrease ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) presentations in the initial phases globally [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. In the United States, the pandemic is re-escalating and for many parts of the world, the pandemic is only now reaching the height of its intensity. New York City has emerged as an epicenter of this unprecedented pandemic [4]. Given the relentless global spread of COVID-19, we believe that a single-center STEMI experience can contribute to the growing literature and offer insight into how STEMI cases may behave during a second surge. Herein we present our single-center experience at an epicenter of the pandemic, before and during the current pandemic.

2. Material and methods

This was a retrospective, observational study, which included consecutive suspected STEMI patients from March 1 to August 31, 2019 (pre-pandemic period) comparing them to the same time period in 2020 (pandemic period), at a 591-bed tertiary referral center in Nassau County, New York. We compared acute myocardial infarction (AMI) team activations during both periods, as well as door-to-balloon time and inpatient outcomes. Additionally, we sought to describe the subset of COVID-19-positive patients with suspected STEMI.

All patients in both cohorts had activation of the AMI team with high clinical suspicion for STEMI. Patients in both cohorts who were referred for emergent cardiac catheterization signed informed consent forms for cardiac catheterization with possible percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and hemodynamic support prior to the procedure. Cardiac catheterization was performed in a sterile cardiac catheterization laboratory. Arterial access was obtained either via the transfemoral or transradial approach.

Patients during the pandemic period who were referred for emergent cardiac catheterization were treated with the presumption that all could have COVID-19. We converted one dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory to a negative-pressure room. Furthermore, we adopted a practice of maximum protection using personal protective equipment for all cases with a terminal cleaning protocol following every procedure. All patients during the pandemic period were tested with reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction to detect SARS-CoV-2 on at least two nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected 24 h apart. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 did not delay transportation to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Point-of-care ultrasonography was performed in the emergency department when necessary to help clarify the diagnosis. There was a low threshold to perform early intubation in the emergency department in patients with tenuous respiratory status before cardiac catheterization.

This study complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and was reviewed by our institutional review board and deemed exempt. A single author had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the data analysis. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture.

2.1. Statistical analysis

We summarize patients' demographic and clinical characteristics using mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, and frequency (%). Comparisons with respect to continuous variables were performed using two-sample t-test. Comparisons with respect to binary variables were performed using Chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were done using SAS 9.4®.

3. Results

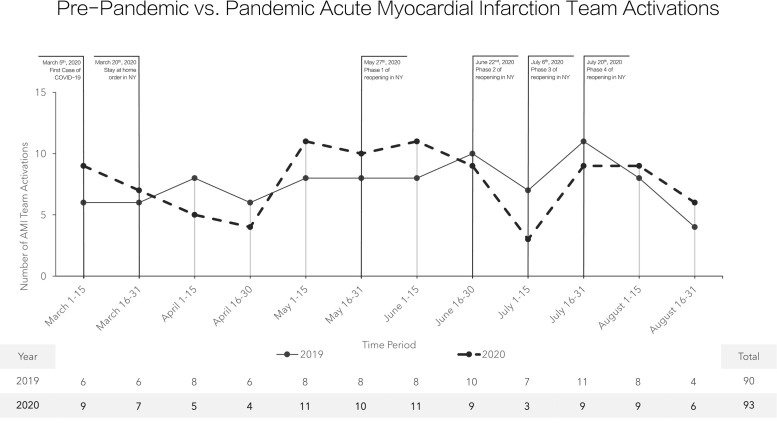

The AMI team was activated for a total of 183 patients during both periods. There were no differences among the clinical characteristics of all patients in both cohorts (Table 1 ). There were a similar number of AMI team activations during the pandemic period (n = 93) compared to the pre-pandemic period (n = 90) (Fig. 1 ). For those taken emergently to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, chest pain remained the predominant symptom during the pandemic as it was pre-pandemic (93.8% vs. 95.6%; p = 0.7140) (Table 2 ). In these patients, there was a trend toward higher Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) scores during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic patients (154.6 vs. 139.0; p = 0.0617). STEMI was confirmed during invasive coronary angiography in 89.9% of patients during the pandemic period and 89.2% of patients during the pre-pandemic period. Left ventricular ejection fractions on ventriculography (41.2% vs. 42.3%, p = 0.7023) and left ventricular end-diastolic pressures (22.0 mmHg vs. 24.9 mmHg, p = 0.0547) were similar between cohorts. During the pandemic period, we observed a trend toward longer door-to-balloon times (95.9 min vs. 74.4 min, p = 0.0587). Despite this, there was similar inpatient length of stay (5.0 days vs. 3.6 days, p = 0.0901) and inpatient mortality (9.2% vs. 13.2%, p = 0.5876) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of all patients during pre-pandemic period (March 1, 2019–August 31, 2019) compared to those during the pandemic period (March 1, 2020–August 31, 2020).

| Pre-pandemic (n = 90) |

Pandemic (n = 93) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 62.5 ± 14.2 | 63.5 ± 13.7 | 0.6424 |

| Male sex (%) | 66.7 | 59.1 | 0.3588 |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 6.4 | 29.8 ± 11.1 | 0.7267 |

| Clinical risk factors | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 63.3 | 62.4 | 1.0000 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 60.0 | 57.0 | 0.7644 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 34.4 | 29.0 | 0.5253 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 23.3 | 24.7 | 0.8639 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting (%) | 2.2 | 6.5 | 0.2786 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention (%) | 18.9 | 14.0 | 0.4271 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Chest pain (%) | 90.0 | 83.9 | 0.1131 |

| Shock (%) | 25.6 | 35.5 | 0.2618 |

| Cardiac arrest (%) | 17.8 | 19.4 | 0.8527 |

| Mean laboratory values | |||

| White blood cells (K/μL) | 11.7 ± 4.5 | 11.1 ± 4.2 | 0.4040 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 0.1827 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 179.2 ± 259.9 | 145.9 ± 334.6 | 0.5170 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 83.4 ± 241.8 | 87.3 ± 219.9 | 0.9205 |

| Peak troponin I (ng/mL) | 123.4 ± 167.2 | 129.6 ± 185.8 | 0.8157 |

| Inpatient outcomes | |||

| Mean length of stay (days) | 3.8 ± 3.2 | 4.6 ± 5.6 | 0.2512 |

| Inpatient death (%) | 11.1 | 19.4 | 0.1508 |

Values are mean ± SD or n/N (%).

Fig. 1.

Pre-pandemic vs. pandemic acute myocardial infarction team activations.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients who were offered emergent cardiac catheterization during the pre-pandemic period (March 1, 2019–August 31, 2019) compared to those during the pandemic period (March 1, 2020–August 31, 2020).

| Pre-pandemic (n = 68) |

Pandemic (n = 65) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 61.8 ± 13.5 | 61.1 ± 9.6 | 0.7409 |

| Male sex (%) | 67.6 | 66.2 | 1.0000 |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.8 ± 5.9 | 30.2 ± 12.6 | 0.3963 |

| Clinical risk factors | |||

| Hypertension (%) | 60.3 | 60.0 | 1.0000 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 55.9 | 58.5 | 0.8611 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 33.8 | 27.7 | 0.4596 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 17.6 | 23.1 | 0.5196 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting (%) | 1.5 | 4.6 | 0.3582 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention (%) | 14.7 | 16.9 | 0.8139 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Chest pain (%) | 95.6 | 93.8 | 0.7140 |

| Shock (%) | 26.2 | 38.5 | 0.1889 |

| Cardiac arrest (%) | 17.6 | 16.9 | 1.0000 |

| ECG findings | |||

| Maximum ST elevation (mm) | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 3.5 ± 3.4 | 0.7305 |

| Total ST elevation (mm) | 7.8 ± 4.5 | 9.9 ± 11.9 | 0.2283 |

| Mean laboratory values | |||

| White blood cells (K/μL) | 11.4 ± 4.1 | 11.3 ± 3.9 | 0.8289 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 0.1710 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 205.8 ± 280.5 | 108.4 ± 117.5 | 0.0231 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 92.0 ± 270.3 | 57.7 ± 55.1 | 0.3655 |

| Peak troponin I (ng/mL) | 162.5 ± 176.4 | 165.7 ± 202.1 | 0.9251 |

| Cardiac catheterization | |||

| Door-to-balloon time (min) | 74.4 ± 46.1 | 95.9 ± 66.9 | 0.0587 |

| Mean LVEDPa (mmHg) | 24.9 ± 8.4 | 22.0 ± 8.3 | 0.0547 |

| Mean ejection fraction (%) | 42.3 ± 15.7 | 41.2 ± 13.1 | 0.7023 |

| Mean TIMIb thrombus grade | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0730 |

| Thrombectomy (%) | 16.2 | 27.7 | 0.1412 |

| Left anterior descending artery PCIc (%) | 33.8 | 46.2 | 0.1603 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump (%) | 29.4 | 20.0 | 0.2312 |

| Impella (%) | 5.9 | 7.7 | 0.7402 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (%) | 4.4 | 3.1 | 1.0000 |

| Inpatient outcomes | |||

| GRACEd score | 139.0 ± 47.9 | 154.6 ± 48.1 | 0.0617 |

| Mean length of stay (days) | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 5.0 ± 6.2 | 0.0901 |

| Inpatient death (%) | 13.2 | 9.2 | 0.5876 |

Values are mean ± SD or n/N (%).

LVEDP: left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

TIMI: thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events.

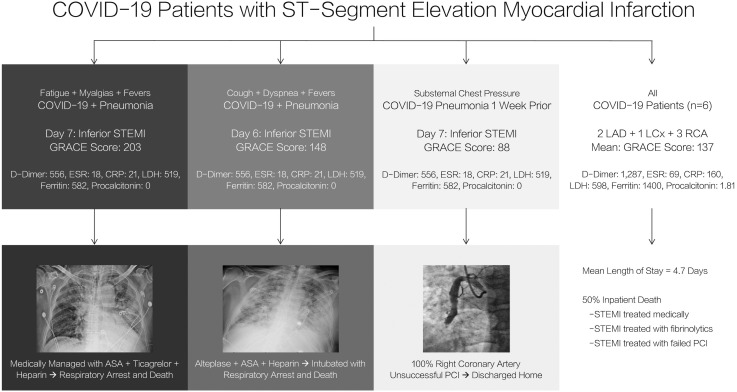

3.1. COVID-19 patients with suspected STEMI

From March 1 through August 31, 2020, there were 6 activations of the AMI team for COVID-19-positive patients with high clinical and electrocardiographic suspicion for STEMI. Of these, 2 patients were not offered emergent cardiac catheterization.

The first patient was a 75-year-old male with hypertension who presented with non-productive cough, dyspnea, and fever found to be in sepsis secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. On the 6th day, the patient developed substernal chest pressure with electrocardiogram demonstrating inferior STEMI. Given his increasing oxygen requirements and tenuous respiratory status, emergent cardiac catheterization was deferred. The patient was administered half-dose alteplase, as there were no absolute contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy. He was subsequently intubated and died from respiratory arrest.

The second patient was a 75-year-old male with hypertension who presented with fatigue, myalgias and fevers found to be in sepsis secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. On the 7th day, his troponin-I was found to be 32.9 ng/mL with electrocardiogram demonstrating inferior STEMI with Q-waves. Given the lack of chest pain, tenuous respiratory status and unclear timing of myocardial infarction, emergent cardiac catheterization was deferred. The patient was not offered fibrinolytic therapy because of the unclear timing of his event and, thus, was medically managed, passing from respiratory arrest.

The remaining 4 patients presented to the emergency department and were referred for emergent cardiac catheterization with high clinical suspicion and electrocardiographic evidence of STEMI. One of the patients was a 49-year-old with substernal chest pain found to be hemodynamically stable with inferior STEMI referred for emergent cardiac catheterization. The culprit vessel was an approximately 6-mm-diameter aneurysmal mid-right coronary artery with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) thrombus grade 5 thrombus treated with eptifibatide, aspiration thrombectomy, and balloon angioplasty. Despite this, percutaneous coronary intervention was unsuccessful, with complete occlusion of the vessel at the mid-portion, and the patient was treated medically, discharged home two days later. The rest of the patients (3) were successfully treated with primary PCI. Summary of clinical characteristics, laboratory data, presenting data, cardiac catheterization, and outcomes of the subset of patients during the pandemic with confirmed COVID-19 can be found in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Summary of COVID-19 cases.

4. Discussion

In our series of patients at our single tertiary referral center in New York with suspected STEMI, comparing those before and during the initial emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were a similar number of AMI team activations, mimicking the seasonal variability seen in 2019, with chest pain remaining the predominant symptom, and the majority of patients demonstrating angiographic evidence of STEMI yielding similar inpatient outcomes. For patients referred for emergent cardiac catheterization during the pandemic, additional investigation and use of personal protective equipment for each case resulted in a signal toward increased door-to-balloon times. Despite this, we observed similar inpatient outcomes during the pandemic as were observed prior to the pandemic. Among the subset of 6 COVID-19 patients with STEMI, those offered primary PCI (4) survived their hospitalization, whereas the remaining 2 expired, one of whom was treated with thrombolytics.

Following a brief period of stability in cases, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be re-intensifying, overwhelming healthcare systems across the world [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 have not yet been fully clarified, but early literature has demonstrated that patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease are among the highest risk [[5], [6], [7], [8],13]. Furthermore, there has been significant uncertainty of the diagnosis and management of STEMI given the heterogeneity of presentations during the pandemic [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. There is a paucity of STEMI literature directly comparing time periods prior to and during the pandemic.

Our study, albeit relatively small, directly compared data regarding patients at a single tertiary-care referral center with suspected STEMI at an epicenter during the initial emergence of the current pandemic to data from the same time period in 2019 before the pandemic, demonstrating a similar number of AMI team activations between both periods, increasing by just 3.3% during the pandemic. This is in contrast to previously published data reporting a decrease in the volume of patients presenting with STEMI by as much as 50% [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21],23]. None of the studies directly compared data from the same time period before and during the pandemic. For many parts of the United States, the pandemic is surpassing previous infection rates, and for parts of the world, the pandemic is only now reaching the height of its intensity. For this reason, we strongly believe that despite the modest sample size, this study offers insight in preparation for subsequent surges of infection and to those suffering through the pandemic as New York was just a few months earlier.

A Chinese study compared only 7 patients from January 25 through February 10, 2020, to 108 patients from February 1, 2018, through January 31, 2019, demonstrating a mean increase in door-to-balloon time of 25.5 min, of which a delay of on average 12.5 min occurred upon arrival to the cardiac catheterization laboratory [20]. These patients had STEMIs that occurred from 8 am to 8 pm on weekdays. The major cause of delay was cited as infection control measures and further history taking to ensure diagnosis. Our study, also utilizing proper protective equipment for all staff, but including STEMIs that presented 24 h a day, 7 days a week, demonstrated a signal toward increased door-to-balloon times. Despite this, inpatient length of stay and inpatient mortality were similar in both cohorts.

In Bergamo, Italy, protocols were put into place to concentrate personnel and STEMI centers during the pandemic [19]. STEMI volume decreased by 37% in March 2020 when compared to the monthly average from the previous year. Our study directly compared data from six months (March through August) in consecutive years (2019 to 2020), which best accounts for seasonal variation. In Italy, formal use of personal protective equipment and early intubation led to an increase in delays as it did in China [19,20]. We saw increased door-to-balloon times during the pandemic as well. The majority of patients in Italy were offered primary PCI, as was the case in our study (69.9%). Increased thrombus burden was reported in the Italian study as well, although we did not see this trend in our study (mean TIMI thrombus grade of 4.7 in 2019 to 4.2 in 2020, p = 0.0730).

Spain was among the hardest hit countries early in the pandemic, which peaked in early April 2020. In Madrid, Spain, saturation of emergency medical services led to significant delays in presentation as well [19]. This study reported a decrease of STEMI patients presenting to hospital of 50% when compared to the weeks before the pandemic. We chose to compare consecutive months during the pandemic to the same months in 2019 to more accurately account for normal disparities in monthly STEMI volume. This resulted in a similar pattern of seasonal variability in the spring and summer of 2019 and 2020. Spain also observed an increase in the use of fibrinolytics, predominantly used at non-PCI-capable centers [19]. Our tertiary referral center is a PCI-capable center which, before this pandemic, had not used fibrinolytics in many years. In our cohort, just one patient with COVID-19 pneumonia and severe respiratory failure was treated with alteplase, suffering respiratory arrest and death.

In the United States, a study of 9 high-volume primary PCI centers across the country compared STEMI data after March 1, 2020, to STEMI data from January 1, 2019, to February 28, 2020 [16]. The study reported a decrease in STEMI volume of 38% between the two time periods with a mean decrease in STEMI activations of 8.3 activations per month per institution. Decreases in STEMI volume were attributed to avoidance of medical facilities, misdiagnosis, and increases in the use of pharmacologic reperfusion strategies during the pandemic. Our study postulates a similar mechanism for the lengthier door-to-balloon times observed. Our smaller, single primary PCI center study demonstrated a small increase in STEMI activations during the pandemic when directly comparing March 1 through August 31, 2020, to data from March 1 through August 31, 2019. It was difficult to assess the full impact of the pandemic on volumes at our institution, as patients may have delayed or avoided presenting to hospitals during the pandemic, subsequently presenting as late complications or cardiac arresting at home. In the small subset of patients with COVID-19 and high likelihood of having STEMI who were not offered emergent cardiac catheterization and primary PCI, we saw much worse outcomes. This reinforces the recommendations and robust literature that primary PCI should remain the standard of care for STEMI patients who are eligible [25].

Early literature demonstrates that COVID-19 has had a substantial impact on the number of patients presenting to hospitals with STEMI [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20],23]. However, many of these studies compare time periods directly before the onset of the pandemic and few were conducted in the United States (Table 3 ). Our single-center experience in one of the epicenters of the pandemic, New York, demonstrated a similar pattern of STEMI presentations compared to the same time period last year, mimicking the seasonable variability observed in 2019. More importantly, there was a signal toward an increase in door-to-balloon times amid the pandemic. Despite this disturbing trend, our study provides reassuring data regarding outcomes in patients taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for primary PCI during the pandemic, with similar inpatient length of stay and mortality compared to 2019. This carries significant implications for future healthcare and policy with regard to additional surges of the pandemic. Clarification of diagnosis, universal adoption of personal protective equipment for all cases, and terminal cardiac catheterization laboratory cleaning protocols appear to increase door-to-balloon times without affecting inpatient outcomes during the pandemic. These findings reinforce the importance of individualized cardiac care and a focus on the safety of healthcare workers, with an understanding that primary PCI should remain the standard of care for patients with STEMI, even during the pandemic.

Table 3.

Comparison of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) studies during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

| Study/region | Pre-pandemic population |

Pandemic population |

Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time interval | Patients | Time interval | Patients | ||

| Our studya New York |

March 2019–September 2019 | 90 | March 2020–August 2020 | 93 | Similar AMI team activations Longer door-to-balloon times Similar mortality and LOS |

| Bangalore, et al., 2020 [15] New York |

– | – | March 2020–April 2020 | 18 | High prevalence of non-obstructive disease in STEMI |

| Garcia, et al., 2020 [16] Multicenter |

January 2019–February 2020 | 2970 | March 2020 | 138 | Fewer AMI team activations 38% reduction |

| Case, et al., 2020 [22] Washington, DC |

– | – | March 2020–June 2020 | 129 | Worse outcomes in STEMI if COVID-19-positive |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; LOS: length of stay; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

The only study directly comparing two identical time intervals in successive years.

4.1. Limitations

There are several key limitations to our descriptive study. This study was retrospective, which reflects the treatment biases of our physicians. Our study was limited to one tertiary-care center in Nassau County, New York. Thus, our sample sizes were smaller than larger multi-centered studies, and inpatient outcomes must be cautiously interpreted as such. We were unable to evaluate whether or not there were patients with STEMI who did not or could not seek care during the pandemic. Furthermore, we were not able to accurately collect data on symptom-onset-to-balloon time in our patients. Delays in seeking or deferring care have a significant impact on outcomes but could not be fully assessed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to rapidly evolve, as does our understanding of its implications on the cardiovascular system and, in particular, STEMI. Our single-center study, at an epicenter of the pandemic, demonstrated a similar seasonal variability in AMI team activations when compared to 2019 but a trend toward longer door-to-balloon time likely secondary to infection control measures and additional investigation to clarify diagnosis. Despite this trend in door-to-balloon time, inpatient length of stay and mortality remained unchanged. An overwhelming majority of patients referred for emergent cardiac catheterization demonstrated angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture, confirming the diagnosis of STEMI. As we continue to manage these patients, in anticipation of subsequent surges, our approach should continue to focus on the safety of healthcare workers and individualized cardiac care, with an understanding that primary PCI remains the standard of care for STEMI.

References

- 1.Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C., Nguyen T.V., Nguyen H.T., Le H.Q., et al. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus update. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [Available from]

- 5.Inciardi R.M., Adamo M., Lupi L., Cani D.S., Di Pasquale M., Tomasoni D., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., Crawford J.M., McGinn T., Davidson K.W., et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasselli G., Pesenti A., Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020;323:1545–1546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basso C., Leone O., Rizzo S., De Gaspari M., van der Wal A.C., Aubry M.C., et al. Pathological features of COVID-19-associated myocardial injury: a multicentre cardiovascular pathology study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3827–3835. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombardi C.M., Carubelli V., Iorio A., Inciardi R.M., Bellasi A., Canale C., et al. Association of troponin levels with mortality in Italian patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019: results of a multicenter study. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1274–1280. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peretto G., Sala S., Caforio A.L.P. Acute myocardial injury, MINOCA, or myocarditis? Improving characterization of coronavirus-associated myocardial involvement. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2124–2125. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi S., Qin M., Cai Y., Liu T., Shen B., Yang F., et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of myocardial injury in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2070–2079. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalid N., Chen Y., Case B.C., Shlofmitz E., Wermers J.P., Rogers T., et al. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) and the heart - an ominous association. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:946–949. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawalha K., Abozenah M., Kadado A.J., Battisha A., Al-Akchar M., Salerno C., et al. Systematic review of COVID-19 related myocarditis: insights on management and outcome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bangalore S., Sharma A., Slotwiner A., Yatskar L., Harari R., Shah B., et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19 - a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2478–2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia S., Albaghdadi M.S., Meraj P.M., Schmidt C., Garberich R., Jaffer F.A., et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng F., Tu L., Yang Y., Hu P., Wang R., Hu Q., et al. Management and treatment of COVID-19: the Chinese experience. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:915–930. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pessoa-Amorim G., Camm C.F., Gajendragadkar P., De Maria G.L., Arsac C., Laroche C., et al. Admission of patients with STEMI since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey by the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roffi M., Guagliumi G., Ibanez B. The obstacle course of reperfusion for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction in the COVID-19 pandemic. Circulation. 2020;141:1951–1953. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam C.F., Cheung K.S., Lam S., Wong A., Yung A., Sze M., et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong. China Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yerasi C., Case B.C., Forrestal B.J., Chezar-Azerrad C., Hashim H., Ben-Dor I., et al. Treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during COVID-19 pandemic. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:1024–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Case B.C., Yerasi C., Forrestal B.J., Shea C., Rappaport H., Medranda G.A., et al. Comparison of characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction with versus without coronarvirus-19. Am J Cardiol. 2021;144:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Said K., El-Baghdady Y., Abdel-Ghany M. Acute coronary syndromes in developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2518–2521. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bu J., Chen M., Cheng X., Dong Y., Fang W., Ge J., et al. Consensus of Chinese experts on diagnosis and treatment processes of acute myocardial infarction in the context of prevention and control of COVID-19 (first edition) Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40:147–151. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D., Casey D.E., Jr., Chung M.K., de Lemos J.A., et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]