Abstract

Mosaic animals have provided the platform for many fundamental discoveries in developmental biology, cell biology, and other fields. Techniques to produce mosaic animals by mitotic recombination have been extensively developed in Drosophila melanogaster but are less common for other laboratory organisms. Here, we report mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over (MAGIC), a new technique for generating mosaic animals based on DNA double-strand breaks produced by CRISPR/Cas9. MAGIC efficiently produces mosaic clones in both somatic tissues and the germline of Drosophila. Further, by developing a MAGIC toolkit for 1 chromosome arm, we demonstrate the method’s application in characterizing gene function in neural development and in generating fluorescently marked clones in wild-derived Drosophila strains. Eliminating the need to introduce recombinase-recognition sites into the genome, this simple and versatile system simplifies mosaic analysis in Drosophila and can in principle be applied in any organism that is compatible with CRISPR/Cas9.

Analysis of mosaic animals has been crucial in developmental and cell biology; this study describes a versatile, simple, and likely widely-applicable technique, MAGIC (mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over), for generating mosaic animals based on DNA double-strand breaks produced by CRISPR/Cas9.

Introduction

Mosaic animals contain genetically distinct populations of cells that have arisen from 1 zygote. Mosaic animals have historically played important roles in the study of pleiotropic genes, developmental timing, cell lineage, neural wiring, and other complex biological processes. Given its genetic tractability, Drosophila has been a major system for generating and studying such mosaics [1], which have led to important discoveries such as developmental compartments [2], cell autonomy [3], and maternal effects of zygotic lethal genes [4]. Mosaic analysis is currently used to study tumor suppressors [5], signaling pathways [6], sleep–wake behaviors [7], cell fates [8], and neuronal lineages [9], among other biological processes.

The earliest mosaic analyses relied on spontaneous mitotic recombination [10], rare events in which a DNA double-strand break (DSB) during the G2 phase of the cell cycle is repaired by homologous recombination, resulting in the reciprocal exchange of chromosomal arms between homologous chromosomes distal to the site of the DNA crossover (reviewed in [11]). Ionizing radiation, such as X-rays [12], cause DSBs and thus were later used in Drosophila to increase the baseline level of mitotic recombination [13]. However, ionizing radiation breaks genomic DNA at random locations and is associated with a high degree of lethality.

To overcome these limitations, the yeast Flippase (Flp)/FRT system was introduced into Drosophila to mediate site-specific recombination at FRT sites [14,15], enabling the development of an ever-expanding toolbox with enhanced power and flexibility for mosaic analysis [15–19]. This system requires that both homologous chromosomes carry FRT sites at the same position proximal (relative to the centromere) to the gene of interest, and an independent marker on one of the homologs to allow visualization of the genetically distinct clones [15]. For mosaic analysis in the Drosophila germline, a dominant female sterility (DFS) ovoD1 transgene was combined with Flp/FRT methods, allowing production of, and selection for, germline clones homozygous for a mutation of interest in a heterozygous mother [20,21]. In this “Flp-DFS” technique, egg production from ovoD1-containing heterozygous and homozygous germline cells is blocked, resulting in progeny derived exclusively from germline clones lacking ovoD1 that were generated by mitotic recombination [22]. Mosaic analysis based on somatic recombination has also been achieved in mice using the Cre-LoxP system and the reconstitution of fluorescent protein genes as markers [23,24]. Despite these successes, site-specific recombination systems have not been widely used for mitotic recombination in model animals beyond Drosophila melanogaster due to the challenging task of introducing recombinase-recognition sites into centromere-proximal regions for every chromosome.

Given the power of mosaic animals in biological research, it would be useful to have a more general approach for inducing interhomolog mitotic recombination in any organism, circumventing the challenges just mentioned. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has great potential for extending mosaic analysis, because it can create targeted DSBs in the genomic DNA of a wide array of organisms [25]. This binary system requires only the Cas9 endonuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) that specifies the DNA target site [26], both of which can be introduced into the cell independently of the location of the target site. CRISPR/Cas9-induced DSBs can be repaired either by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). So far, most CRISPR/Cas9 applications in animals have been focused on NHEJ-mediated mutagenesis and HDR-mediated gene replacement [27]. Recently, several studies demonstrated that CRISPR/Cas9-induced DSBs can also induce targeted mitotic recombination in yeast and in the germlines of Drosophila, houseflies, and tomatoes [28–31], suggesting the possibility of exploiting this property of CRISPR/Cas9 for mosaic analysis. Here, we report mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over (MAGIC), a novel technique for mosaic analysis based on CRISPR/Cas9. This method can be used to generate mosaic clones in both the Drosophila soma and germline. Based on this method, we built a convenient toolkit to generate and label mosaic clones for genes located on chromosome arm 2L. We demonstrate the success of our toolkit for mosaic analysis in the soma and the germline and show its applications in analyzing gene functions in neuronal dendrite development. Lastly, we also demonstrate that MAGIC can be used successfully with unmarked wild-derived strains, indicating that this method can in principle be extended to organisms for which recombinase-based toolkits are not yet available.

Results

Rationale for MAGIC

MAGIC relies on the action of gRNA/Cas9 in a proliferating cell during G2 phase to generate a DSB at a specific position on 1 chromatid of a homologous pair (Fig 1A). The DSB can induce a crossover between this chromatid and a chromatid from the homologous chromosome, resulting in an exchange of chromosome segments between the 2 chromatids at the location of the DSB. During the subsequent mitotic segregation of chromosomes, recombinant chromatids sort into different daughter cells in a G2-X segregation event, generating “twin spots,” which contain 2 genetically distinct populations of cells homozygous for the chromosome segment distal to the exchange [32]. Alternatively, recombinant chromatids can sort into the same daughter cell in G2-Z segregation, resulting in 2 daughter cells that still maintain heterozygocity at every locus [32]. By introducing a genetic marker distal to the gRNA target site in one of the homologous chromosomes, it is possible to distinguish homozygous twin spots among heterozygous cells based on the gain of copies of and/or loss of the genetic marker.

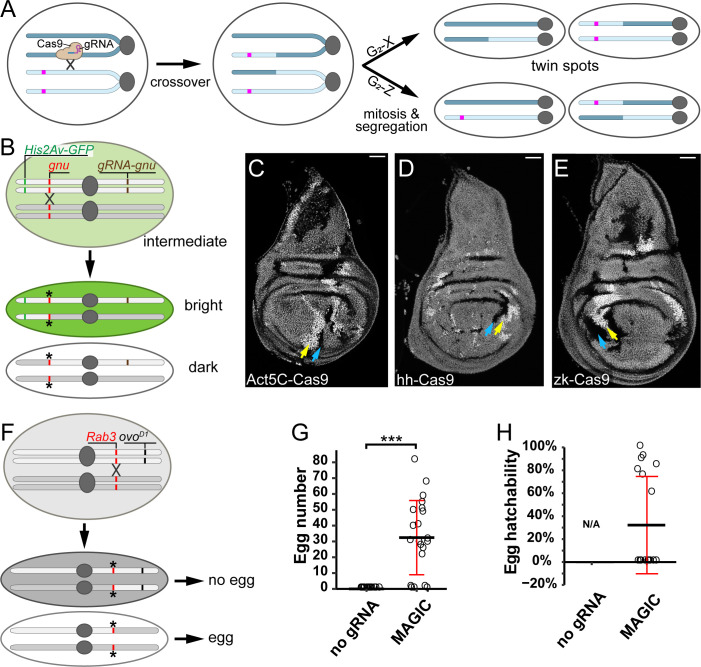

Fig 1. CRISPR-induced crossover generates somatic and germline clones in Drosophila.

(A) A diagram illustrating the principle of MAGIC. The magenta bar indicates a marker that is lost from 1 daughter cell and becomes homozygous in the other in G2-X-generated twin spots. (B) Strategy for generating mosaic clones using the His2Av-GFP marker and a crossover at the gnu locus. Locations of the GFP marker (His2Av-GFP, green bar), the gRNA (gnu-gRNA, brown bar), and the target of the gRNA (gnu, red bar) are shown. Asterisks indicate mutated gRNA target sites. (C–E) Mosaic clones in wing discs visualized by levels of His2Av-GFP expression, as described in the text. A pair of arrows indicate His2Av-GFP+/+ (yellow) and His2Av-GFP−/− (blue) cells in each panel. Clones were induced by Act5C-Cas9 (C), hh-Cas9 (D), and zk-Cas9 (E). Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) Strategy for generating and detecting clones in the female germline using ovoD1. Figure labels are analogous to those in 1B; the gRNA is on another chromosome. (G) Number of eggs produced by females carrying nos-Cas9 and ovoD1, with (MAGIC) or without (no gRNA) gRNA-Rab3. ***p < 0.001, Student t test. n = number females: no gRNA (n = 18); MAGIC (n = 18). (H) Hatchability of eggs produced females carrying nos-Cas9 and ovoD1, with (MAGIC) or without (no gRNA) gRNA-Rab3. n = number females: no gRNA (N/A); MAGIC (n = 18). For quantifications in G and H, black bar, mean; red bar, SD. The data underlying this Figure can be found in S1 Data. GFP, green fluorescent protein; gRNA, guide RNA; MAGIC, mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over.

Using CRISPR-induced crossover to generate clones in the Drosophila soma and germline

For our initial tests of the ability of MAGIC to generate mosaic clones in somatic tissues, we used ubiquitously expressed gRNAs to induce DSBs at the gnu locus and a ubiquitous fluorescent marker, His2Av-GFP [33], to trace clones (Fig 1B). Both His2Av-GFP and gnu are located on the left arm of chromosome 3 (3L), and His2Av-GFP is distal to gnu. We chose gnu as our gRNA target because we had already made an efficient gRNA-gnu line for other purposes (to be published elsewhere); furthermore, this gene is only required maternally for embryonic development [34], so mutations of gnu are not expected to affect the viability or growth of somatic cells. We induced clones using 3 different Cas9 transgenes, each of which is expressed in the developing wing disc under the control of a different enhancer. With all 3 Cas9s, we observed twin spots consisting of bright His2Av-GFP homozygous clones abutting GFP-negative clones in the midst of His2Av-GFP/+ heterozygous cells (Fig 1C–1E) in every imaginal disc examined, demonstrating the feasibility of MAGIC for generating somatic mosaics.

Given that CRISPR/Cas9 is active in both the soma and the germline of Drosophila [35–37], we next tested for MAGIC clone induction in the germline by using the DFS technique and the germline-specific nos-Cas9 [36] (S1A Fig). We used an ovoD1 transgene located on chromosome arm 2R and induced DSBs at the Rab3 locus, which is located on the same arm proximal to the location of ovoD1 (Fig 1F). Since Rab3 is a nonessential gene expressed only in neurons [38], its disruption in the female germline should affect neither egg production nor embryonic development of the progeny. Due to the dominant effect of ovoD1, restoration of egg production can only result from mitotic recombination proximal to ovoD1 (e.g., at Rab3 in this case), followed by generation of ovoD1-negative clones. As expected, control females that contained ovoD1 and nos-Cas9, but not gRNA-Rab3, did not produce any eggs. In contrast, most females carrying all 3 components produced 20 to 90 eggs each (Fig 1G), many of which hatched into larvae (Fig 1H), suggesting successful mitotic recombination.

The results above together show that, like the Flp/FRT system, MAGIC is an effective approach for generating homozygous clones via mitotic recombination in both Drosophila soma and germline, consistent with the high frequency of CRISPR-induced exchange of chromosomal arms previously demonstrated in the Drosophila germline [28].

A toolkit for generating labeled clones for genes on chromosome arm 2L

Towards making MAGIC a general approach for analyzing Drosophila genes, we built a toolkit for genes located on chromosome arm 2L as a proof of principle. We designed transgenic constructs that each integrate 2 features simultaneously: ubiquitously expressed gRNAs that target a pericentromeric region and a ubiquitously expressed marker for visualizing clones. The constructs were inserted into a distal position of 2L. When a gRNA-marker-bearing chromosome is used together with an unmodified second chromosome, clones that are homozygous for nearly the entirety of the unmodified arm can be visualized by the loss of the marker. Positive labeling with pMAGIC utilizes a Gal80 marker [18], which suppresses Gal4-driven expression of a fluorescent reporter (Fig 2A). Therefore, only the cells that lose the Gal80 transgene will be fluorescently labeled, similarly to mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) [18]. In contrast, negative MAGIC (nMAGIC) expresses a nuclear blue fluorescent protein (nBFP) reporter, such that clones homozygous for the unmodified arm are marked by the loss of nBFP expression (Fig 2B).

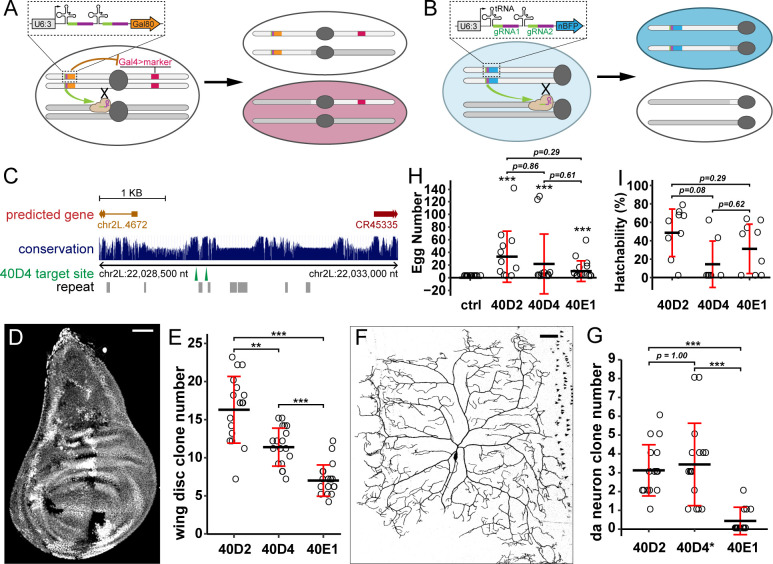

Fig 2. A toolkit for generating labeled clones for genes on chromosome arm 2L.

(A) Strategy of pMAGIC for generating positively labeled clones for genes on 2L using Gal80. (B) Strategy of nMAGIC for genes on 2L using nuclear BFP marker. (C) A map for gRNA-(40D4) target sites derived from the UCSC Genome Browser. The height of the blue bar corresponds to the level of conservation among 23 Drosophila species. The locations of predicted genes (thick line, exon or mature RNA; thin line, intron; arrow, gene orientation), repeated DNA sequences (gray boxes), gRNA target sites (green arrowheads), and chromosomal coordinates are indicated. (D) A wing imaginal disc showing twin-spot clones generated by gRNA-40D2(nBFP) paired with hh-Cas9. (E) Number of clones in wing discs using 3 different gRNA(nBFP) constructs. n = number of discs: 40D2 (n = 17); 40D4 (n = 18); 40E1 (n = 18). **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001; Welch ANOVA and Welch t tests, p-values corrected using Bonferroni method. (F) A C4da neuron clone generated by gRNA-40D2(Gal80) paired with SOP-Cas9 and ppk>CD4-tdTom. (G) Quantification of C4da clones using 3 different gRNA(Gal80) constructs. n = number of larvae: 40D2 (n = 16); 40D4 (n = 16); 40E1 (n = 16). Clones were visualized by ppk>CD4-tdTom. ***p ≤ 0.001; Welch ANOVA and Welch t tests, p-values corrected using the Bonferroni method. The asterisk on 40D4 indicates frequent labeling of C3da clones. (H) Number of eggs produced by using ovoD1(2L), nos-Cas9, and 3 different gRNA(nBFP) constructs. The ctrl has no gRNA. n = number of females: ctrl (n = 13); 40D2 (n = 12); 40D4 (n = 12); 40E1 (n = 14). Asterisks are from post hoc single sample t tests that compare the EMM of each gRNA against the control (μ = 0); ***p ≤ 0.001. p-Values are from contrasts of EMMs of each gRNA (excluding control). EMMs are based on a negative binomial model. All p-values were corrected using the Tukey method. (I) Hatchability of eggs produced by females carrying ovoD1(2L), nos-Cas9, and gRNA(nBFP) constructs. n = number of females: 40D2 (n = 9); 40D4 (n = 7); 40E1(n = 9). p-Values are from contrasts of EMMs of proportions of hatched/nonhatched eggs for each gRNA based on a binomial, mixed-effects model and were corrected using the Tukey method. For E, G, and H: black bar, mean; red bar, SD. Scale bars, 50 μm. The data underlying this Figure can be found in S1 Data. BFP, blue fluorescent protein; ctrl, control; EMM, estimated marginal mean; gRNA, guide RNA; nBFP, nuclear blue fluorescent protein; nMAGIC, negative MAGIC; pMAGIC, positive MAGIC.

To identify appropriate gRNA target sites, we surveyed the pericentromeric sequences of 2L for sequences that met 3 criteria: (1) being reasonably conserved so that DSBs can be induced in most Drosophila strains; (2) not functionally critical and being distant from essential sequences so that indel mutations in nearby regions would not disrupt important biological processes; and (3) unique in the genome and predicted to have a low likelihood of off-targeting. Therefore, for each MAGIC construct, we chose a pair of nonrepeat gRNA target sequences in an intergenic region to enhance the chance of DSBs. The 2 gRNA target sequences are closely linked to reduce the risk of large deletions (Fig 2C). In addition, we preferentially chose sequences that are conserved among closely related Drosophila species (D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. sechellia) but not in more distant species. Considering the varying efficiencies of different gRNA target sequences, we selected 3 pairs of gRNAs targeting 3 chromosomal locations (40D2, 40D4, and 40E1) and tested their ability to produce clones in wing discs, neurons, and the germline.

Clones were induced in a specific tissue by a Cas9 transgene that is expressed in precursor cells of that tissue. We used hh-Cas9 [39] for nMAGIC in the wing imaginal disc (Fig 2D), SOP-Cas9 [39] for pMAGIC in larval class IV dendritic arborization (C4da) sensory neurons (Fig 2F), and nos-Cas9 for the female germline (S1B Fig). gRNAs targeting 40D2 consistently performed the best in generating clones in wing discs and C4da neurons (Fig 2E and 2G) and appear to be the most efficient in the germline, even though the differences in the germline were not statistically significant (Fig 2H and 2I). Although the overall efficiencies of gRNA-40D2 and gRNA-40D4 in inducing clones in da neurons are similar (Fig 2G and S2A Fig), gRNA-40D4 induced more clones in a different type of neuron (class III). These results indicate that we have created an efficient MAGIC toolkit for genes located on chromosome arm 2L. Analogous toolkits will be made for other chromosome arms, using the same methods, and will be reported separately once they are generated. A list of potential gRNA target sites for those chromosome arms is in S2 Table.

Inducible clone generation and comparison with Flp/FRT-mediated mosaic analysis

Existing Flp/FRT-recombination systems allow temporal control of clone induction through the use of Flp transgenes driven by heat shock (HS) promoters [40,41], providing great flexibility to mosaic analysis. To test if gRNA-induced crossing-over can generate clones via similar approaches, we paired nMAGIC line gRNA-40D2(nBFP) with a HS-inducible Cas9 that was reported recently [42]. A single 1-hour HS at 37°C of early third instar larvae robustly induced clones in the wing imaginal disc (Fig 3B and 3C), whereas larvae of the same genotype that did not experience HS showed nearly no clones in the wing disc (Fig 3A and 3C). These results show that MAGIC is compatible with inducible Cas9.

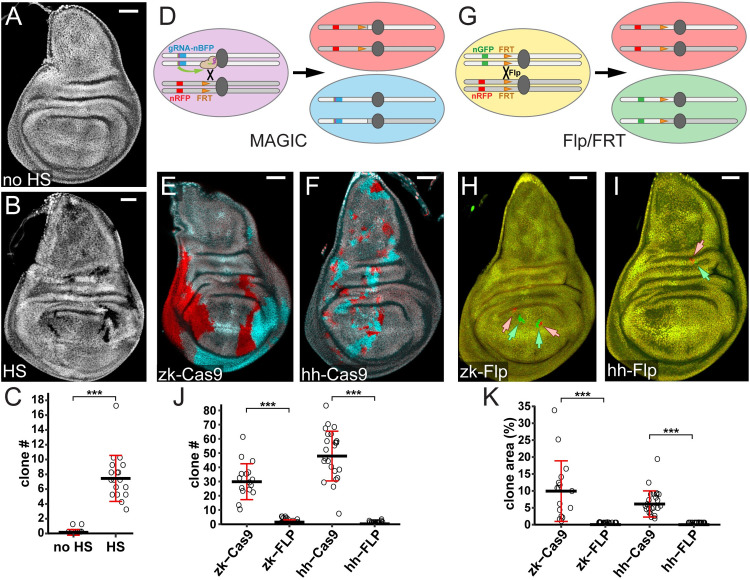

Fig 3. Inducible MAGIC and comparison with Flp/FRT-mediated mosaic analysis.

(A and B) Wing imaginal discs of animals with gRNA-40D2(BFP) and HS-Cas9 with (B) and without (A) HS at 72 h at egg laying. (C) Quantification of clone number per disc induced by HS. n = number of discs: no HS (n = 13), HS (n = 18). ***p ≤ 0.001, Welch 2-sample t test. (D) Diagram of twin spot labeling using gRNA-40D2(nBFP) and nRFP FRT40A chromosomes via MAGIC. (E and F) Wing imaginal discs showing clones generated by MAGIC using zk-Cas9 (E) and hh-Cas9 (F) visualized with nBFP (cyan) and nRFP (red). (G) Diagram of twin spot labeling using nRFP FRT40A and nGFP FRT40A chromosomes through Flp/FRT-mediated site-specific recombination. (H and I) Wing imaginal discs showing clones generated by FRT/Flp-mediated site-specific recombination using zk-Flp (H) and hh-Flp (I) and visualized with nGFP (green, indicated by green arrows) and nRFP (red, indicated by pink arrows). (J and K) Quantification of clone number per disc (J) and percentage of total clone area (K). n = number of discs: zk-Cas9 (n = 16), zk-FLP (n = 18), hh-Cas9 (n = 23), hh-FLP (n = 19). ***p ≤ 0.001, Welch 2-sample t test. Scale bars, 50 μm. The data underlying this Figure can be found in S1 Data. Flp, Flippase; FRT, flippase recognition target; gRNA, guide RNA; HS, heat shock; MAGIC, mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over; nBFP, nuclear blue fluorescent protein; nGFP, nuclear green fluorescent protein; nRFP, nuclear red fluorescent protein.

As gRNA-induced DSBs and Flp/FRT yield interchromosomal exchange through distinct mechanisms, we wondered if MAGIC and Flp/FRT exhibit different efficiencies of clone induction. To directly compare these 2 systems in the wing imaginal disc, we chose 2 pairs of Cas9 and Flp transgenes, with each pair controlled by an identical enhancer (zk or hh). FRT-mediated recombination was induced between two FRT40A-bearing chromosomes that carry ubiquitously expressed nuclear GFP (nGFP) or nuclear RFP (nRFP) (Fig 3G). FRT40A was selected as the FRT site for comparison because of the availability of 2 different fluorescent markers on FRT40A arms, which makes the measurement of clone numbers and sizes convenient. gRNA-induced crossing-over occurred between gRNA-40D2(nBFP) and nRFP FRT40A chromosomes (Fig 3D). As expected, both zk-Cas9 and hh-Cas9 generated clones robustly in the wing disc, with zk-Cas9 causing fewer but larger clones and hh-Cas9 causing more but smaller clones (Fig 3E, 3F, 3J, and 3K). Surprisingly, very few small clones were observed in wing discs when the FRT40A chromosomes were paired with either Flp transgene (Fig 3H–3K). Because clone frequencies were low with both Flp lines, we did not detect statistical differences between them. Given that the low efficiency of Flp/FRT in these experiments may be due to the specific site of FRT40A, these results may not indicate a general difference in efficiency between MAGIC and Flp/FRT. Nevertheless, our results show that MAGIC can be reliably and efficiently used for mosaic analysis.

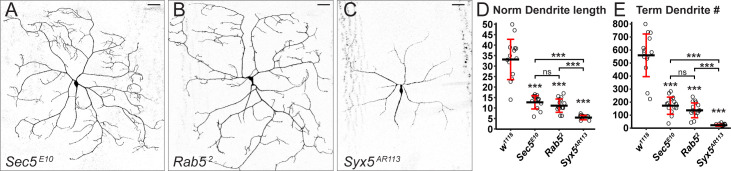

Mosaic analysis of neuronal dendrite development

To evaluate the utility of our MAGIC toolkit for characterizing gene function at the single-cell level, we combined the pMAGIC line gRNA-40D2(Gal80) with mutations on 2L that affect dendrite morphogenesis in C4da neurons by disrupting vesicular trafficking. We first used 2 genes, Secretory 5 (Sec5) [43] and Rab5 [44], which have been shown to be required for dendrite growth. We observed marked dendrite reduction in C4da clones carrying homozygous mutations in these genes (Fig 4A, 4B, and 4D), recapitulating previously published results using MARCM with the same mutants [43,44]. A third gene, Syntaxin 5 (Syx5), was identified in our unpublished RNA interference (RNAi) screens. Clones carrying a null mutation of Syx5 produced the most dramatic dendrite reduction, with almost all terminal dendrites eliminated (Fig 4C–4E), consistent with the expected role of Syx5 in the endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi vesicle trafficking [45]. Therefore, our MAGIC reagents for 2L can be used to characterize gene functions in single cells with a power analogous to that of MARCM but with a much simpler system.

Fig 4. Mosaic analysis of example genes in neuronal dendrite development.

(A–C) MAGIC clones of C4da neurons mutant for Sec5E10 (A), Rab52 (B), and Syx5AR113 (C), visualized by ppk>MApHS. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D and E) Quantification of normalized dendrite length (total dendrite length/segment width) (D) and terminal branch number (E) of C4da clones of wild-type control (w1118) and mutants. n = number neurons: w1118 (n = 14); Sec5E10 (n = 14); Rab52 (n = 15); Syx5AR113 (n = 10). The asterisk above each genotype indicates comparison with the control. ***p ≤ 0.001, ns, not significant, Welch ANOVA and Welch t tests, p-values corrected using the Bonferroni method. The data underlying this Figure can be found in S1 Data. MAGIC, mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over.

Generation of clones by MAGIC in fly lines with wild-derived genomes

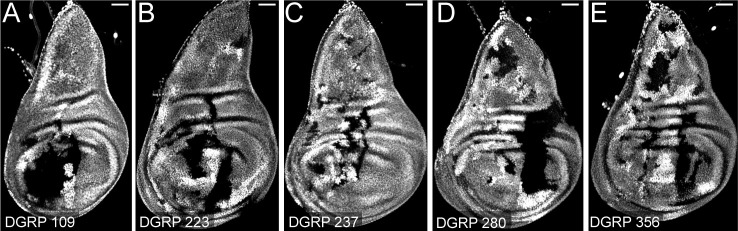

An advantage of MAGIC compared to Flp/FRT-based mitotic recombination systems is that MAGIC does not require that FRT sites be present on the homologous chromosomes to mediate crossing-over. MAGIC is therefore easier to apply to fly strains with wild-derived genomes and even potentially to organisms in which genetic systems like Flp/FRT are not routinely available. To test the applicability of MAGIC to unmarked strains with wild-derived genomes, we crossed gRNA-40D2(nBFP); hh-Cas9 to 5 randomly chosen lines from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) [46], a set of unique strains established from flies captured in the wild. In all cases, we observed efficient clone induction in wing imaginal discs (Fig 5A–5E), demonstrating the potential of MAGIC for allowing future mosaic analysis of the function of natural alleles residing on wild-derived chromosomes.

Fig 5. MAGIC generates clones with DGRP lines.

(A–E) Clones in wing imaginal discs by pairing gRNA-40D2(BFP); hh-Cas9 with DGRP line 109 (A), 223 (B), 237 (C), 280 (D), and 356 (E). Scale bars, 50 μm. DGRP, Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel; MAGIC, mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over.

Discussion

We present here a new technique that we named MAGIC (mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over) for mosaic analysis based on CRISPR-induced mitotic recombination. We show that MAGIC is capable of efficiently producing mosaic tissues in both the Drosophila soma and germline, using gRNAs targeting various chromosomal locations. Integrated gRNA-marker constructs enable visualization of homozygous clones by the presence or absence of fluorescent reporters. As demonstrated by our 2L toolkit, MAGIC is simple and effective to use. Similar MAGIC reagents will be generated for all other chromosome arms to allow for genome-wide characterization of gene functions.

Existing techniques for mosaic analysis have led to many major advances and findings in cell and developmental biology [2–4]. MAGIC provides additional flexibility, in that it does not require any modifications of the test chromosome, such as recombination with an existing FRT site. Integrating gRNAs and genetic markers into 1 transgenic construct also reduces the number of necessary genetic components. As a result, gRNA-marker transgenes can be combined with existing mutant libraries to perform MAGIC with very little additional effort. Moreover, with MAGIC, the site of mitotic recombination is limited only by the gRNAs that can be designed. Therefore, MAGIC can in principle permit mosaic analysis of mutations that were previously very difficult or impossible to study with existing techniques, including those near centromeres and the ones associated with transgenic constructs that contain FRT sequences [47].

Successful use of MAGIC requires 4 considerations. First, gRNAs should be carefully designed to eliminate, or minimize, potential off-target effects. Off-target prediction algorithms based on empirical evidence [48–51], which are constantly being improved, should facilitate this process, even though the possibility of off-targeting cannot be completely excluded. Second, our results suggest that the gRNA target sequence strongly influences the efficiency of clone induction, likely by affecting the frequency of DNA DSBs in premitotic cells. Therefore, for mosaic analysis of a specific chromosomal arm, it is beneficial to compare a few candidate gRNA targets and select the most effective one. Third, because perfect DSB repair will recreate the gRNA target site and allow for one more round of Cas9 cutting, most cells that have expressed Cas9 in their lineages are expected to eventually harbor indel mutations that disrupt the gRNA target site, regardless of whether or not the DSBs have led to mitotic recombination. However, this caveat can be mitigated by choosing gRNA sites in noncritical sequences, which can be validated by crossing gRNA lines to a ubiquitous Cas9 or by comparing gRNA-induced control clones to wild-type cells. To facilitate selection of appropriate gRNA target sites, we list 3 sets of potential gRNA target sequences for each major chromosome arm in S2 Table. Finally, since only DNA DSBs in the G2 phase can lead to clone generation, the timing of Cas9 action is expected to be critical for MAGIC. For the cell type in question, an ideal Cas9 should be expressed in the precursor cells, as too early expression can mutate gRNA target sites prematurely and too late expression will lead to unproductive DSBs.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of MAGIC is its potential for use with wild-derived Drosophila strains and in organisms beyond Drosophila. DGRP and other wild-derived strains have played important roles in identification of natural alleles that are associated with certain phenotypic variations [52–55]. However, it has been difficult to investigate the effect of homozygosity for many alleles within these strains using available genetic tools (e.g., Flp/FRT, Gal4 drivers, and fluorescent markers) for technical reasons. For example, recombining existing FRT sites into DGRP chromosomes without removing potentially interacting genetic variants present in these stocks will be very challenging. By crossing MAGIC lines carrying both gRNA-marker and Cas9 to DGRP strains, one can validate causal effects of specific natural alleles in cellular or developmental processes in a natural-genome context and a tissue-specific manner. Similarly, the DGRP can also be used in MAGIC-based genetic screens to identify natural alleles that, when made homozygous, can cause or modify certain phenotypes. For these applications, germline-expressing Cas9 lines should be avoided to prevent heritable mutations of gRNA target sites.

Importantly, MAGIC can, in theory, be utilized in a wide array of organisms that are compatible with CRISPR/Cas9 [56]. In model systems that allow for transgenesis of gRNA-marker constructs, such as mouse, zebrafish, and Xenopus, Cas9 can be introduced by injection or virus transduction to further simplify genetic manipulations. It is worth noting that Drosophila is unusual in that its homologous chromosomes pair during mitosis, which facilitates mitotic recombination [57], and that its recombinant chromatids resulting from interchromosomal exchange in G2 phase predominantly undergo X segregation [32]. Although other organisms may not share these properties, homology-directed recombination in mitotic cells has been documented in other organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammals [58–60]. Therefore, the flexibility and power of mosaic analysis that are familiar to the Drosophila research community will likely be in reach of researchers who study organisms which have not, or have rarely, been amenable to mosaic analysis.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks and husbandry

See the Key Resource Table (S1 Table) for details of fly stocks used in this study. Most fly lines were either generated in the Han and Wolfner labs or obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center or the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel [46]. HS-Cas9 [42] was a gift from Tuzmin Lee. hh-Flp was generated by converting R28E04-Gal4attP2 into a Flp-expressing line using the homology assisted CRISPR knock-in (HACK) method [61]. The details of the conversion will be reported elsewhere. All flies were grown on standard yeast-glucose medium, in a 12:12 light/dark cycle, at room temperature (22 ± 1°C, for the egg laying assay) or 25°C (for larval assays) unless otherwise noted. Virgin males and females for mating experiments were aged for 3 to 5 days. Virgin females were aged on yeasted food for germline mosaic analysis.

To test germline clone induction, we combined nos-Cas9 and ovoD1, and then the gRNA in 2 sequential crosses in schemes shown in S1 Fig.

To visualize clones of C4da neurons, we used ppk-Gal4 UAS-CD4-tdTom [67,68] (Fig 2) and ppk-Gal4 UAS-MApHS [69] (Fig 3, only the tdTom channel is shown).

To temporally induce clones in the wing disc, larvae (72 hours after egg laying) of w; gRNA-40D2(nBFP)/+; HS-Cas9/+ were heat shocked for 1 hour at 37°C, and their discs were examined at 96 hours after egg laying.

Molecular cloning

zk-Cas9: The entry vector pENTR221-ZK2 [62] and the destination vector pDEST-APIC-Cas9 (Addgene 121657) were combined in a Gateway LR reaction to generate the expression vector pAPIC2-ZK2-Cas9.

MAGIC gRNA-marker vectors: gRNA-marker vectors were constructed similarly to pAC-U63-tgRNA-Rev (Addgene 112811, [39]) but have either a ubi-nBFP (in pAC-U63-tgRNA-nlsBFP) or a ubi-Gal80 (in pAC-U63-tgRNA-Gal80) marker immediately after the U6 3′ flanking sequence. The markers contain a Ubi-p63E promoter, mTagBFP-NLS or Gal80 coding sequence, and His2Av polyA sequence. The Ubi-p63E promoter was amplified from Ubi-CasExpress genomic DNA using the oligonucleotides TTAATGCGTATGCATTCTAGTggccatggcttgctgttcttcgcgttc and TTGGATTATTctgcgggcagaaaatagagatgtggaaaattag. mTagBFP-NLS was synthesized as a gBlock DNA fragment (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa 52241, United States of America). Gal80 coding sequence was PCR amplified from pBPGAL80Uw-4 (Addgene 26235) using the oligonucleotides aaaaaaaaatcaaaATGAGCGGTACCGATTACAACAAAAGGAGTAGTGTGAG and GCCGACTGGCTTAGTTAattaattctagaTTAAAGCGAGTAGTGGGAGATGTTG. The His2Av polyA sequence was PCR amplified from pDEST-APLO (Addgene 112805). DNA fragments were assembled together using NEBuilder DNA Assembly (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts 01938, USA).

gRNA expression vectors: For gnu and Rab3, gRNA target sequences were cloned into pAC-U63-tgRNA-Rev as described [39]. For gRNAs targeting 2L, gRNA target sequences were cloned into pAC-U63-tgRNA-nlsBFP and pAC-U63-tgRNA-Gal80 using NEBuilder DNA Assembly. In the gRNA-marker constructs, the tRNA between the first and second gRNAs is a Drosophila glutamine tRNA (cagcgcGGTTCCATGGTGTAATGGTTAGCACTCAGGACTCTGAATCCTGCGATCCGAGTTCAAATCTCGGTGGAACCT) instead of a rice glycine tRNA.

Injections were carried out by Rainbow Transgenic Flies (Camarillo, California 93012, USA) to transform flies through φC31 integrase-mediated integration into attP docker sites.

pAPIC2-ZK2-Cas9 and gRNA-marker constructs were integrated into the attPVK00037 site on the second chromosome, and expression vectors containing gRNAs targeting Rab3 or gnu were integrated into the attPVK00027 site on the third chromosome. Transgenic insertions were validated by genomic PCR or sequencing.

Identification of gRNA target sequence

gRNA target sequences for Rab3 and gnu were identified as described previously [39]. Briefly, 2 gRNA prediction methods were used: sgRNA Scorer 2.0 [63] (https://crispr.med.harvard.edu) and Benchling (www.benchling.com). Candidate target sequences were those that obtained high on-target scores in both algorithms. CasFinder [48] was used to identify and reject any sequences with more than 1 target site. Two target sequences against coding exons for all splice isoforms were chosen for each targeted gene. gRNA target sequences for 2L were identified by visually scanning through pericentromeric sequences using UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) following principles described in the Results section. The on- and off-target scores were calculated using CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net/) [64]. S2 Table lists target sequences that are used in this study and those recommended for creating gRNA-marker constructs for other chromosome arms.

Live imaging of neurons

Live imaging was performed as previously described [62]. Briefly, animals were reared at 25°C in density-controlled vials for between 96 and 120 hours after egg laying (to obtain third to late third instar larvae). Larvae were mounted in glycerol, and their C4da neurons at segments A1 to A6 were imaged using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope with a 20× oil objective and a z-step size of 3.5 μm.

Imaginal disc imaging

Imaginal disc dissections were performed as described previously [65]. Briefly, wandering third instar larvae were dissected in a small petri dish filled with cold PBS. The anterior half of the larva was inverted and the trachea and gut were removed. The sample was then transferred to 4% formaldehyde in PBS and fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the imaginal discs were placed in SlowFade Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts 02451, USA) on a glass slide. A coverslip was lightly pressed on top. Imaginal discs were imaged using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope with a 20× oil objective.

Assays for germline mosaic analysis

To monitor mitotic recombination events resulting in germline clone generation, we performed egg laying and egg hatchability assays as detailed in [66], with the exception of using Canton-S males in place of ORP2 males as wild-type mates. Hatchability was calculated only for females that laid eggs. Females that laid no eggs were eliminated from hatchability calculations to avoid inflation of false-zero values.

Image analysis and quantification

Counting of wing disc clones was completed in Fiji/ImageJ. Counting of neuronal clones was completed manually during the imaging process.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R. Student t test was conducted for egg laying data using Rab3 and kni gRNAs. For egg laying data using the 2L toolkit, we performed estimated marginal means contrasts between gRNAs and post hoc 1-sample t tests using a generalized linear model with a negative binomial response. For hatchability data using the 2L toolkit, we performed estimated marginal means contrasts between proportions of hatched/nonhatched eggs for each gRNA using a generalized linear mixed-effects model with a binomial response. For all contrasts, p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Tukey method. For the comparison of gRNAs using wing disc and neuronal clone data as well as the analysis of normalized total dendrite length, we performed Welch analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise post hoc Welch t tests. p-Values from the multiple post hoc Welch t tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. For hs-Cas9 data and the comparison of MAGIC and the FRT/Flp method, we performed Welch t tests.

Supporting information

(A) Crossing scheme for germline clone induction using gRNA-Rab3, ovoD1(2R), and nos-Cas9. (B) Crossing scheme for testing gRNAs for 2L in germline clone induction. The gRNAs used in this test were gRNA(nBFP) lines.

(TIF)

(A) Distribution of da neuron clones in each segment using gRNA(Gal80) for 40D2 and 40D4. n = number of neurons: 40D2 (n = 47); 40D4 (n = 52). The data underlying this Figure can be found in S1 Data. Larva drawn by G. T. K.

(TIF)

This table lists the sources of Drosophila lines, recombinant DNAs and reagents, software, and algorithms used in this study.

(XLSX)

This table lists target sequences on chromosome 2L that were used in this study and those recommended for creating gRNA-marker constructs for the other chromosome arms. *Doench’16 on-target score; a higher score predicts a higher efficiency. **CFD Specificity Score; a higher score corresponds to a lower off-target probability.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Tzumin Lee, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (https://bdsc.indiana.edu/index.html) (NIH P40OD018537), and the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (http://dgrp2.gnets.ncsu.edu/) for fly stocks; Cedric Feschotte, Andy Clark, Eric Alani, and Marcus Smolka for advice on gRNA design; Cornell CSCU consultants Stephen Parry and Erika Mudrak for advice on statistics; Michael Goldberg, John Schimenti, Erich Brunner, and Konrad Basler for critical reading and helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DFS

dominant female sterility

- DGRP

Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel

- DSB

double-strand break

- Flp

Flippase

- gRNA

guide RNA

- HDR

homology-directed repair

- HS

heat shock

- MAGIC

mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over

- MARCM

mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker

- nBFP

nuclear blue fluorescent protein

- NHEJ

nonhomologous end joining

- nMAGIC

negative MAGIC

- pMAGIC

positive MAGIC

- Sec5

Secretory 5

- Syx5

Syntaxin 5

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Cornell start-up funds and NIH grants (R01NS099125 and R21OD023824) awarded to C.H., by NIH grants (R01/R37-HD038921 and R03-HD101732) awarded to M.F.W., by an NIH training grant (T32-GM07273) awarded to the Cornell BMCB graduate program (A.P. Bretscher, P.I.) and that supported S.E.A. during part of this work, and by a Hunter R. Rawlings III Cornell Presidential Scholarship (RCPRS) awarded to G.K. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. G.K., S.E.A., C.H., and M.F.W. received full or partial salary support from Cornell University; S.E.A., A.S., B.W., and C.H. received partial or full salary support from the NIH grants noted above.

References

- 1.Perrimon N. Creating mosaics in Drosophila. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42 (3):243–7. 10.1387/ijdb.9654004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Bellido A, Ripoll P, Morata G. Developmental compartmentalization in the dorsal mesothoracic disc of Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1976;48 (1):132–47. 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90052-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heitzler P, Simpson P. The choice of cell fate in the epidermis of Drosophila. Cell 1991;64 (6):1083–92. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90263-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrimon N, Engstromt L, Mahowald AP. Zygotic Lethals With Specific Maternal Effect Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Loci on the X Chromosome. Genetics. 1989;121:333–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Fat and Expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through Warts. PNAS. 2007;104 (51):20362–7. 10.1073/pnas.0706722105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang X, Shi L, Cao J, He F, Li R, Zhang Y, et al. The Sterile 20-Like kinase tao controls tissue homeostasis by regulating the hippo pathway in drosophila adult midgut. J Genet Genomics. 2014;41 (8):429–38. 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung BY, Ro J, Hutter SA, Miller KM, Guduguntla LS, Kondo S, et al. Drosophila Neuropeptide F Signaling Independently Regulates Feeding and Sleep-Wake Behavior. Cell Rep. 2017;19 (12):2441–50. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu DJ-K, Jasper H. Control of Intestinal Cell Fate by Dynamic Mitotic Spindle Repositioning Influences Epithelial Homeostasis and Longevity. Cell Rep. 2019;28(11):2807–23.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee T. Generating mosaics for lineage analysis in flies. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2014;3 (1):69–81. 10.1002/wdev.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern C. Somatic Crossing Over and Segregation In Drosophlia melanogaster. Genetics. 1936;21:625–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin R, Binari R, Perrimon N. Genetic odyssey to generate marked clones in Drosophila mosaics. PNAS. 2014;111 (13):4756–63. 10.1073/pnas.1403218111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller HJ. The Production of Mutations by X-Rays. PNAS. 1928;14 (9):714–26. 10.1073/pnas.14.9.714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu T, Rubin G. The effort to make mosaic analysis a household tool. Development. 2012;139:4501–1503. 10.1242/dev.085183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golic KG, Lindquist S. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the drosophila genome. Cell. 1989;59 (3):499–509. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu T, Rubin G. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin R, Sustar A, Bonvin M, Binari R, Del Valle RA, Hohl AM, et al. The twin spot generator for differential Drosophila lineage analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6 (8):600–2. 10.1038/nmeth.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison DA, Perrimon N. Simple and efficient generation of marked clones in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1993;3 (7):424–33. 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90349-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic Analysis with a Repressible Cell Marker for Studies of Gene Function in Neuronal Morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–61. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H-H, Chen C-H, Shi L, Huang Y, Lee T. Twin-spot MARCM to reveal the developmental origin and identity of neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12 10.1038/nn.2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou T-B, Perrimon N. Use of a Yeast Site-specific Recombinase to Produce Female Germline Chimeras in Drosophila. Genetics. 1992;131:643–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrimon N, Gans M. Clonal analysis of the tissue specificity of recessive female-sterile mutations of Drosophila melanogaster using a dominant female-sterile mutation Fs(1)K1237. Dev Biol. 1983;100 (2):365–73. 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou T-B, Noll E, Perrimon N. Autosomal P[ovoD1] dominant female-sterile insertions in Drosophila and their use in generating germ-line chimeras. Development. 1993;119:1359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henner A, Ventura PB, Jiang Y, Zong H. MADM-ML, a Mouse Genetic Mosaic System with Increased Clonal Efficiency. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 (10):77672 10.1371/journal.pone.0077672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers in Mice. Cell. 2005;121 (3):479–92. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sander JD, Keith JJ. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32 (4):347–55. 10.1038/nbt.2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A Programmable Dual-RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–21. 10.1126/science.1225829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salsman J, Dellaire G. Precision genome editing in the CRISPR era. Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;95:187–02. 10.1139/bcb-2016-0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner E, Yagi R, Debrunner M, Beck-Schneider D, Burger A, Escher E, et al. CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks trigger recombination between homologous chromosome arms. Life Science Alliance. 2019;2 (3):e201800267–e. 10.26508/lsa.201800267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayut SF, Melamed Bessudo C, Levy AA. Targeted recombination between homologous chromosomes for precise breeding in tomato. Nat Commun. 2017;8 (15605). 10.1038/ncomms15605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinze SD, Kohlbrenner T, Ippolito D, Meccariello A, Burger A, Mosimann C, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 targeted disruption of the yellow ortholog in the housefly identifies the brown body locus. Sci Rep. 2017;7 (4582). 10.1038/s41598-017-04686-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadhu MJ, Bloom JS, Day L, Kruglyak L. CRISPR-directed mitotic recombination enables genetic mapping without crosses. Science. 2016;352 (6289):1113–6. 10.1126/science.aaf5124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beumer KJ, Pimpinelli S, Golic KG. Induced Chromosomal Exchange Directs the Segregation of Recombinant Chromatids in Mitosis of Drosophila. Genetics. 1998;150 (1):173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarkson M, Saint R. A His2AvDGFP Fusion Gene Complements a Lethal His2AvD Mutant Allele and Provides an in Vivo Marker for Drosophila Chromosome Behavior. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18 (6):457–62. 10.1089/104454999315178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman M, Niisslein-Volhard C, Glover DM. The Dissociation of Nuclear and Centrosomal Division in gnu, a Mutation Causing Giant Nuclei in Drosophila. Cell. 1986. August 1;46(3):457–68. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90666-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, et al. Genome Engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-Guided Cas9 Nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–35. 10.1534/genetics.113.152710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. PNAS. 2014;111 (29):E2967–E76. 10.1073/pnas.1405500111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren X, Sun J, Housden BE, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, et al. Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. PNAS. 2013;110 (47):19012–7. 10.1073/pnas.1318481110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Gendelman HK, Roche JP, Alsharif P, Graf ER. Mutational Analysis of Rab3 Function for Controlling Active Zone Protein Composition at the Drosophila Neuromuscular Junction. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 (8):e0136938–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poe AR, Wang B, Sapar ML, Ji H, Li K, Onabajo T, et al. Mutagenesis Reveals Gene Redundancy and Perdurance in Drosophila. Genetics. 2019;211 (February):459–72. 10.1534/genetics.118.301736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golic MM, Rong YS, Petersen RB, Lindquist SL, Golic KG. FLP-mediated DNA mobilization to specific target sites in Drosophila chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(18):3665–71. Epub 1997/09/15. 10.1093/nar/25.18.3665 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC146935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golic KG. Site-specific recombination between homologous chromosomes in Drosophila. Science. 1991;252 (5008):958–61. 10.1126/science.2035025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia-Marques J, Espinosa-Medina I, Ku K-Y, Yang C-P, Koyama M, Yu H-H, et al. A programmable sequence of reporters for lineage analysis. Nat Neurosci. 2020. 10.1038/s41593-020-0676-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng Y, Lee J, Rowland K, Wen Y, Hua H, Carlson N, et al. Regulation of dendrite growth and maintenance by exocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:4279–92. 10.1242/jcs.174771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satoh D, Sato D, Tsuyama T, Saito M, Ohkura H, Rolls MM, et al. Spatial control of branching within dendritic arbors by dynein-dependent transport of Rab5-endosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10 (10):1164–71. 10.1038/ncb1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardwick KG, Pelham HRB. SED5 encodes a 39-kD integral membrane protein required for vesicular transport between the ER and the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 1992;119 (3):513–21. 10.1083/jcb.119.3.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacKay TFC, Richards S, Stone EA, Barbadilla A, Ayroles JF, Zhu D, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature. 2012;482 (7384):173–8. 10.1038/nature10811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thibault ST, Singer MA, Miyazaki WY, Milash B, Dompe NA, Singh CM, et al. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat Genet. 2004;36 (3):283–7. 10.1038/ng1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aach J, Mali P, Church GM. CasFinder: Flexible algorithm for identifying specific Cas9 targets in genomes. BioRxiv. 2014. 10.1101/005074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):827–32. Epub 2013/07/23. 10.1038/nbt.2647 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3969858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(2):184–91. Epub 2016/01/19. 10.1038/nbt.3437 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4744125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tycko J, Wainberg M, Marinov GK, Ursu O, Hess GT, Ego BK, et al. Mitigation of off-target toxicity in CRISPR-Cas9 screens for essential non-coding elements. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4063 Epub 2019/09/08. 10.1038/s41467-019-11955-7 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6731277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark AG, Silveria S, Meyers W, Langley CH. Nature screen: An efficient method for screening natural populations of Drosophila for targeted P-element insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994. January 18;91(2):719–22. 10.1073/pnas.91.2.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grenier JK, Arguello JR, Moreira MC, Gottipati S, Mohammed J, Hackett SR, et al. Global Diversity Lines-A Five-Continent Reference Panel of Sequenced Drosophila melanogaster Strains. G3: Genes Genomes Genetics. 2015;5:593–603. 10.1534/g3.114.015883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackay TFC, Huang W. Charting the genotype-phenotype map: lessons from the Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2018;7 (1):e289–e. 10.1002/wdev.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shorter J, Couch C, Huang W, Carbone MA, Peiffer J, Anholt RRH, et al. Genetic architecture of natural variation in Drosophila melanogaster aggressive behavior. PNAS. 2015:E3555–E63. 10.1073/pnas.1510104112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrison MM, Jenkins BV, O'Connor-Giles KM, Wildonger J. A CRISPR view of development. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1859–72. 10.1101/gad.248252.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKee BD. Homologous pairing and chromosome dynamics in meiosis and mitosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Gene Structure and Expression. 2004;1677 (1):165–80. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Symington LS, Rothstein R, Lisby M. Mechanisms and Regulation of Mitotic Recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics . 2014;198 (3):795 10.1534/genetics.114.166140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishiyama J, Mikuni T, Yasuda R. Virus-Mediated Genome Editing via Homology-Directed Repair in Mitotic and Postmitotic Cells in Mammalian Brain. Neuron. 2017;96(4):755–68.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaco I. Canela As, Vera E, Blasco MA. Centromere mitotic recombination in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181 (6):885–92. 10.1083/jcb.200803042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin C-C, Potter CJ. Editing Transgenic DNA Components by Inducible Gene Replacement in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2016;203 (4):1613 10.1534/genetics.116.191783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poe AR, Tang L, Wang B, Li Y, Sapar ML, Han C. Dendritic space-filling requires a neuronal type-specific extracellular permissive signal in Drosophila. PNAS. 2017:E8062–E71. 10.1073/pnas.1707467114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chari R, Yeo NC, Chavez A, Church GM. SgRNA Scorer 2.0: A Species-Independent Model to Predict CRISPR/Cas9 Activity. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6 (5):902–4. 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Concordet J-P, Haeussler M. CRISPOR: intuitive guide selection for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing experiments and screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46 (W1):W242–W5. 10.1093/nar/gky354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han C, Belenkaya TY, Wang B, Lin X. Drosophila glypicans control the cell-to-cell movement of Hedgehog by a dynamin-independent process. Development. 2004;131:601–11. 10.1242/dev.00958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Q, Wolfner MF. The Drosophila Trpm channel mediates calcium influx during egg activation. PNAS. 2019;116 (38):18994–9000. 10.1073/pnas.1906967116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han C, Jan LY, Jan Y-N. Enhancer-driven membrane markers for analysis of nonautonomous mechanisms reveal neuron–glia interactions in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108 (23):9673 10.1073/pnas.1106386108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han C, Wang D, Soba P, Zhu S, Lin X, Jan LY, et al. Integrins Regulate Repulsion-Mediated Dendritic Patterning of Drosophila Sensory Neurons by Restricting Dendrites in a 2D Space. Neuron. 2012;73 (1):64–78. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han C, Song Y, Xiao H, Wang D, Franc NC, Jan LY, et al. Epidermal cells are the primary phagocytes in the fragmentation and clearance of degenerating dendrites in Drosophila. Neuron. 2014;81(3):544–60. Epub 2014/01/09. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.021 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]