Abstract

To date, no effective biological markers have been identified for predicting the prognosis of esophageal cancer patients. Recent studies have shown that eosinophils are independent prognostic factors in some cancers. This study aimed to identify the prognostic impact of eosinophils in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT).

This study enrolled 136 patients who received CCRT for locally advanced unresectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). We evaluated the survival time and clinical pathological characteristics of eosinophils. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival data. The log-rank test was used for univariate analysis and the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to conduct a multivariate analysis.

Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that high eosinophil infiltration correlated with better overall survival (OS) (P = .008) and better progression-free survival (PFS) (P = .015). The increase in absolute eosinophil count after CCRT also enhanced OS (P = .005) and PFS (P = .007). The PFS and OS in patients with high blood eosinophil count before CCRT (>2%) was better than those with low blood eosinophil count(<2%) (P = .006 and P = .001, respectively). Additionally, the multivariate analysis revealed that disease stage and high eosinophil infiltration, increased peripheral blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT, and high peripheral blood eosinophil count before CCRT were independent prognostic indicators.

High eosinophil count of tumor site, increased peripheral blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT, and high peripheral blood eosinophil count before CCRT are favorable prognostic factors for patients with ESCC treated with CCRT.

Keywords: concurrent chemoradiotherapy, eosinophil, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, peripheral blood, prognosis, tumor site

1. Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma is one of the most common malignancies worldwide and the sixth most common cause of cancer-related death, with >400,000 new confirmed cases annually.[1,2] Esophagectomy is one of the primary treatment modalities, and early detection and treatment increases the 5-year survival rate to 90%. However, most patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer are already in the advanced stages, with only approximately 20% of cases being resectable.[3,4] In view of this, concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) for esophageal cancer has gained increasing interest, as the combined effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy may be synergistic and complementary for local control and prevention of distant metastasis, thereby enhancing survival.[5] The standard nonsurgical treatment option is mainly based on the results of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85–01 study, which showed that definite CCRT had a 10-year survival rate of 20%.[6,7] Moreover, a high local recurrence rate of 46% was reported after definite CCRT in the RTOG and RTOG trials.[8] To date, no effective biological markers have been identified for predicting the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer.[9]

Prolonged low-grade inflammation or smoldering inflammation is a hallmark of cancer.[10] Among the inflammatory cells implicated in the immune surveillance of cancer, a growing body of evidence suggests a role for eosinophils in carcinogenesis.[11] Eosinophils are components of the immune microenvironment that modulate tumor initiation and progression.[10] The possible function of tumor-associated eosinophils has not yet been elucidated, but an increasing amount of evidence supports the notion that crosstalk between cancer and inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment influences tumor development, progression, and resistance to radiochemotherapy and hence the clinical outcome. In the majority of studies, the presence of eosinophils at either the tumor site or in the peripheral blood is a favorable prognostic factor for some cancers, indicating that eosinophils play an antitumorigenic role in most clinical cancers. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the prognostic impact of eosinophils in peripheral blood and at either tumor site in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who were treated with CCRT.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and tissue samples

A single-center retrospective study was conducted. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Mianyang Central Hospital (approval no. S2020007). As clinical data were analyzed anonymously, the ethics committee agreed to waive the requirement for informed consent from the patients. We retrospectively reviewed 136 patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the advanced stages, primarily treated with CCRT between 2008 and 2018 at Mianyang Central Hospital. Age, sex, stage, differentiation grade of tumors, eosionophil-related disorder, radiation dose, eosinophil count of tumor site, and clinical data on eosinophils in peripheral blood before and after CCRT were recorded. We count eosinophils in tumor site, which includes the tumor itself and the area surrounding the tumor. All patients, except for those clearly identified as deceased in the records, were followed up via telephone or clinical visits. The follow-up deadline was set to May 1, 2020.

We decided to perform all counts in H&E–stained sections, as this technique is most widely used in laboratories. Eosinophils were counted and graded as previously described by Fernandez-Acenero and van Driel et al[using a 40× objective lens per high-power field (HPF, 400 × )measuring0.24 mm2 (Olympus BX45)]: absence of eosinophils, low eosinophil count (<10/0.24 mm2), intermediate eosinophil count (10–50/0.24 mm2), and high eosinophil count (>50/0.24 mm2).[12]

We collected data on eosinophils in the peripheral blood before and after CCRT. The eosinophil count before concurrent CCRT was obtained in the last blood analysis before concurrent CCRT in patients who were admitted without any treatment. The eosinophil count after concurrent CCRT was obtained in the first blood analysis after CCRT. Moreover, we excluded patients with fever and definite infection.

2.2. Statistical analysis

OS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to the last follow-up or until the patients death. PFS was defined as the time from treatment initiation until the first objective tumor progression or death from any cause. Objective tumor progression was determined by biopsy and/or CT, PET/CT, whole body bone scan, or MRI. SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used in statistical analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to conduct a univariate analysis of eosinophils as a predictor of patients OS. A log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions. Cox proportional hazard regression was used in a multivariate analysis of the impact of prognostic factors on survival. In all analyses, P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

A total of 136 patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma were included: 93 men and 43 women, aged41 to 88 years (median, 65 years), constituted the total sample size. All patients came from Sichuan Province. Three patients came from Yanting County in Sichuan Province, one of several regions in China where esophageal cancer is endemic. The other patients were from the county adjacent to Yanting. Disease stages I–III were determined using China's clinical staging criteria for the no operative treatment of esophageal cancer, and the number of patients with stage II disease was the highest (n = 69). The number of patients who received irradiation doses >60 Gy (n = 120) far exceeded the number of patients who received irradiation doses <60 Gy (n = 16). For eosinophil count of tumor site, most eosinophils are in the area surrounding at umor and are rarely found in a tumor (about 2%). Because eosinophils are present in every esophageal cancer tissue, we followed the criteria reported by van Driel et al, dividing our patients into 3 groups: low eosinophil counts (<10/HPF) (n = 18), intermediate eosinophil counts (10–50/HPF) (n = 97), and high eosinophil counts (>50/HPF) (n = 21) (Fig. 1). Taking the relationship with 0.1 × 109 as the cutoff, we divided the absolute eosinophil count into 2 groups. The eosinophil count was divided into 2 groups by the dividing line of 2%. The detailed clinical pathological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no relationship between tumor differentiation and eosinophil count at the tumor site (P = .40, the same result between eosionophil-related disorders and eosinophil count of tumor site (P = .71).

Figure 1.

Infiltration of eosinophils into the esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissues. Eosinophils, the cytoplasmic granules of which are stained bright red, are easily recognizable from other tissues (original magnification 200 × ).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics in 136 patients.

| Clinicopathologic characteristics | Number of cases | Percentage (%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (range) | 65 (41–88) | |

| <70 | 42 | 30.9 |

| ≥70 | 94 | 69.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 93 | 68.4 |

| Female | 43 | 31.6 |

| Differentiation | ||

| Low | 53 | 39.0 |

| Intermediate | 80 | 58.8 |

| High | 3 | 0.2 |

| Somaking | ||

| Yes | 61 | 44.9 |

| No | 75 | 55.1 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 59 | 43.4 |

| No | 77 | 56.6 |

| Eosionophil-related disorder | ||

| Yes (Allergic, Asthmatic) | 15 | 11.0 |

| No | 131 | 89.0 |

| Radiation dose | ||

| ≥60 Gy | 120 | 88.2 |

| <60 Gy | 16 | 11.8 |

| Eosinophil count of tumor site | ||

| Low | 18 | 13.2 |

| Intermediate | 97 | 71.4 |

| High | 21 | 15.4 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 35 | 25.7 |

| II | 69 | 50.7 |

| III | 32 | 23.6 |

| Blood Eosinophilia absolute count | ||

| Before CCRT | ||

| <0.1 × 109 | 62 | 45.6 |

| ≥0.1 × 109 | 74 | 54.4 |

| After CRT | ||

| <0.1 × 109 | 87 | 64.0 |

| ≥0.1 × 109 | 49 | 36.0 |

| Change of after CCRT | ||

| Increase | 47 | 34.6 |

| Decrease or No change | 89 | 65.4 |

| Blood Eosinophilia rate | ||

| Before CCRT (%) | ||

| <2 | 75 | 55.1 |

| ≥2 | 61 | 44.9 |

| After CCRT (%) | ||

| <2 | 84 | 61.8 |

| ≥2 | 52 | 38.2 |

| Change of after CCRT | ||

| Increase | 55 | 40.4 |

| Decrease or No change | 81 | 59.6 |

3.2. Survival

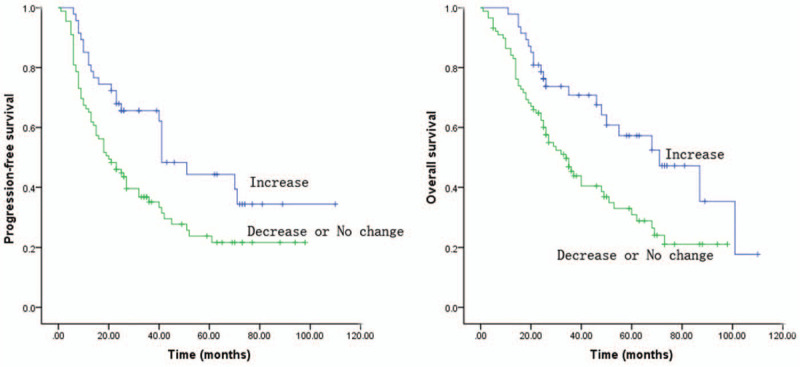

Prognostic significance of eosinophils in peripheral blood and at either tumor site was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Patients with high eosinophil infiltration had significantly better overall survival (OS) (P = .008) and better progression-free survival (PFS) (P = .015) compared with patients with low or intermediate eosinophil infiltration (Fig. 2). The increase in blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT was positively correlated with patient survival. The increase in blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT also enhanced OS (P = .005) and PFS (P = .007) (Fig. 3). The OS and PFS in patients with high blood eosinophil count before CCRT (≥2%) was better than those with low blood eosinophil count (<2%) and both parameters showed significant differences between the 2 groups (P = .001 and P = .006, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients with ESCC: High eosinophil infiltration in ESCC correlated with better overall survival (OS) (P = .008; log-rank test) and better progression-free survival (PFS) (P = .015; log-rank test) compared with low or intermediate eosinophil infiltration.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients with ESCC: The increase in blood absolute eosinophil count after concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) was positively correlated with patient survival. It had enhanced OS (P = .005; log-rank test) and PFS (P = .007; log-rank test).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients with ESCC: The OS and PFS of patients with high blood eosinophil count before CCRT (>2%) was better than those with low blood eosinophil count (<2%) and had significant differences (P = .001 and P = .006, respectively; log-rank test).

Univariate analysis was performed and showed that age, sex, irradiation dose, differentiation grade of tumors, eosionophil-related disorder, smoking and drinking had no correlation with prognosis. High eosinophil count at either tumor site (P = .01), stage of esophageal carcinoma (P < .05), increase in absolute blood eosinophil count after CCRT, and high eosinophil count in peripheral blood before CCRT were significantly associated with prolonged survival (Table 2). Multivariate analysis indicated that clinical stage, eosinophil count of tumor site, increase in blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT, and high blood eosinophil count (≥2%) before CCRT correlated with PFS and OS and that they may be independent prognostic factors that affect the survival times of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of clinical pathological effectors on prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients.

| PFS | OS | |||

| Characteristics | Hazard Ratio (95% CI | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age | ||||

| ≥70 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <69 | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | .36 | 0.79 (0.50–1.27) | .33 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.99 (0.63–1.58) | .98 | 0.89 (0.55–1.44) | .62 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 1.69 (0.63–4.58) | .30 | 1.66 (0.61–4.49) | .32 |

| High | 3.13 (0.43–23.00) | .26 | 3.17 (0.42–23.84) | .26 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 0.80 (0.52–1.22) | .31 | 0.86 (0.55–1.35) | .51 |

| Drinking | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 0.70 (0.46–1.07) | .98 | 0.78 (0.50–1.23) | .29 |

| Eosionophil-related disorder | ||||

| Yes (Allergic, Asthmatic) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 1.36 (0.66–2.81) | .39 | 1.17 (0.56–2.43) | .68 |

| Radiation dose | ||||

| ≥60 Gy | 1 | 1 | ||

| <60 Gy | 1.14 (0.49–2.20) | .71 | 1.098 (0.55–2.20) | .79 |

| Intratumoral eosinophil count | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 0.45 (0.22–0.94) | .03 | 0.47 (0.21–0.91) | .04 |

| high | 0.57 (0.37–0.89) | .01 | 0.53 (0.34–0.84) | .007 |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 1.75 (1.6–2.88) | .03 | 1.69 (1.01–2.82) | .04 |

| III | 1.97 (1.42–2.73) | .001 | 2.00 (1.42–2.83) | .001 |

| Blood Eosinophilia absolute count | ||||

| Before CRT | ||||

| <0.1 × 109 | 1.10 (0.72–1.67) | .68 | 1.14 (0.73–1.78) | .57 |

| ≥0.1 × 109 | 1 | 1 | ||

| After CRT | ||||

| <0.1 × 109 | 1.18 (0.55–1.83) | .48 | 1.12 (0.56–1.71) | .64 |

| ≥0.1 × 109 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Change of after CRT | ||||

| Increase | 1 | 1 | ||

| Decrease or No change | 1.87 (1.16–3.0) | .01 | 2.04 (1.23–3.40) | .006 |

| Blood Eosinophilia rate | ||||

| Before CRT (%) | ||||

| <2 | 1.8 ((1.17–2.75) | .007 | 1.12 ((1.35–3.33) | .001 |

| ≥2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| After CRT (%) | ||||

| <2 | 1.49 (0.96–2.32) | .08 | 1.22 (0.72–2.07) | .06 |

| ≥2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Change of after CRT | ||||

| Increase | 1 | 1 | ||

| Decrease or No change | 1.02 (0.67–1.57) | .92 | 1.05 (0.67–1.64) | .84 |

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of clinical pathological effectors on prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients.

| PFS | OS | |||

| Characteristics | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

| Eosinophil count of tumor site | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 0.53 (0.29–0.99) | .04 | 0.43 (0.23–0.81) | .09 |

| high | 0.23 (0.09–0.55) | .001 | 0.19 (0.07–0.49) | .01 |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 1.95 (1.01–3.54) | .03 | 2.29 (1.19–4.38) | .01 |

| III | 3.45 (1.80–6.59) | .001 | 3.82 (1.91–7.67) | .001 |

| Blood Eosinophili absolute count | ||||

| Change of after CCRT | ||||

| Increase | 1 | 1 | ||

| Decrease or No change | 1.74 (1.01–2.80) | .02 | 1.85 (1.10–3.10) | .02 |

| Blood Eosinophili rate | ||||

| Before CCRT (%) | ||||

| <2 | 1.67 ((1.09–3.58) | .02 | 2.05 ((1.30–3.23) | .002 |

| ≥2 | 1 | 1 | ||

4. Discussion

Among the inflammatory cells implicated in the immune surveillance of cancer, a growing body of evidence suggests the role for eosinophils in carcinogenesis.[11] In several meta-analyses, we discovered that the presence of tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia (TATE) was notably associated with improved OS in patients with solid tumors.[13,14]In clinical practice, the presence of eosinophils at the tumor site is a favorable prognostic factor for most cancers. For example, in gastric,[15,16] colorectal,[12,17–20] nasopharyngeal,[21] oral,[22,23] laryngeal cancers,[24] melanoma,[25–27] small cell esophageal carcinoma,[28] and breast cancer,[29] eosinophils appear play antitumorigenic roles.

Esophageal cancer is usually associated with inflammation; therefore, TATE should be markedly associated with better OS in esophageal carcinoma.[30,31] Zhang et al observed that the infiltration of eosinophils in small cell esophageal carcinoma was significantly increased compared with that in tumor adjacent normal tissues, and eosinophil count was an independent prognostic indicator for small cell esophageal carcinoma.[28] Ishibashiet al published a retrospective study on TATE in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and reported that the number of tumor-associated eosinophils was significantly higher in cases without venous invasion, LN metastasis, and clinical recurrence.[32] Ohashietal. used the same tissue-related eosinophil count method to confirm that TATE is considered to be involved in the biological behavior of early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, especially with regards to their metastatic potential.[33] Similar to the findings of these studies, our study results indicate that high eosinophil infiltration at the tumor site is a favorable prognostic factor for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with CCRT.

Although most studies have analyzed the role of TATE, less is known about the role of circulating eosinophils. A simple blood analysis could reveal the status of the whole immune system and is a convenient and economic method of clinical evaluation in daily practice. In our study, besides paying attention to the relationship between eosinophil infiltration at the tumor site and prognosis, we also observed the predictive and prognostic roles of peripheral blood absolute eosinophil count and rate. Liu et al observed that, according to the hematologic test results before neoadjuvant chemotherapy, patients with higher eosinophilic granulocyte counts had a significantly greater opportunity for an effective response.[32] Different studies have demonstrated the association between peripheral blood eosinophil counts and outcomes in several cancer types. For example, Moreira et al reported that eosinophilia is a prognostic marker in patients with metastatic melanoma.[33] Onesti et al indicated the survival of many breast cancer patients with high eosinophil counts by the 3-year follow-up.[34] Our study not only focused on a certain state of eosinophils in peripheral blood but also found the relationship between the changes in eosinophils in peripheral blood and prognosis before and after CCRT. This indicates that the high blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT and blood eosinophil count (≥2%) before CCRT are favorable prognostic factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the univariate and multivariate analyses.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy can affect the immune microenvironment of tumor patients, and immune cells can reflect the prognosis of patients to a certain extent. As recent studies have suggested, eosinophils contain cytotoxic granular proteins and, upon activation, secrete many cytokines that kill tumor cells. Interleukin-5 secreted by stromal cells of the tumor activates eosinophils, which in turn liberate toxic granules to exert cytotoxic effects on tumor cells.[35] Tumor-infiltrating eosinophils secrete chemo attractant cytokines that guide CD8+ T cells toward the cancer tissue and induce normalization of the tumor vasculature.[29] Eosophil-mediated antitumor function of IL-33 against melanoma opens perspectives for novel cancer immunotherapy strategies.[27] The blood eosinophil count before CCRT may more objectively reflect the immunity of patients than the absolute eosinophil count. After CCRT, the increase in blood absolute eosinophil count may demonstrate the immunity enhancement of patients.

According to the value of the risk ratio, the prognostic and predictive values of eosinophil infiltration at the tumor site are better than those of the tumor stage, and the tumor stage is a better predictor than the blood eosinophil count before concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) and the change in the absolute count of blood eosinophils after CCRT. However, our study was a retrospective study and the number of patients was small. More studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to confirm the value of eosinophil count in the prognosis of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with CCRT.

Our study is the first to report the prognostic impact of eosinophils in peripheral blood and tumor sites in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with CCRT. However, our study is limited by biases inherent to retrospective studies. First, the OS and PFS were larger than those in other studies.[36–38] We attribute this difference to the exclusion of patients with incomplete follow-up data from our study. In China, many patients are not followed regularly after treatment completion and are lost to follow-up, and most die. We excluded patients with missing data, which led to increased OS and PFS. However, this exclusion had similar impacts on different groups. Second, we obtained the eosinophil count after concurrent CCRT in the first blood analysis after CCRT, with analysis time of 7 to 21days.

5. Conclusions

Our study indicates that high eosinophil count of tumor site, increased peripheral blood absolute eosinophil count after CCRT, and high peripheral blood eosinophil count before CCRT are favorable prognostic factors in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with CCRT.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xiaobo Du.

Data curation: Xiyue Yang, Lei Wang, Huan Du, Binwei Lin, Jie. Yi, Xuemei Wen.

Formal analysis: Xiyue Yang, Lei Wang.

Investigation: Xiyue Yang, Lei Wang, Huan Du, Binwei Lin, Jie. Yi, Xuemei Wen, Lidan Geng.

Supervision: Xiaobo Du.

Writing – original draft: Xiyue Yang, Lei Wang.

Writing – review & editing: Xiaobo Du.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CCRT = concurrent chemoradiotherapy, CT = computed tomography, ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NCCN = national comprehensive cancer network, OS = overall survival, PFS = progression-free survival, PET/CT = positron emission computed tomography, RTOG = radiation therapy oncology group, TATE = tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia.

How to cite this article: Yang X, Wang L, Du H, Lin B, Yi J, Wen X, Geng L, Du X. Prognostic impact of eosinophils in peripheral blood and tumor site in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Medicine. 2021;100:3(e24328).

This work was supported by the Mianyang Science and Technology Bureau (15-S01–3).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2241–52. 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li-Li Zhu, Ling Yuan, HuInt J, et al. A meta-analysis of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for advanced esophageal cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128616.Mol Sci. 2014 jun; 15 (6):9718-9734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Herskovic A, Martz K, Al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone inpatients with cancer of the esophagus. New Eng J Med 1992;326:1593–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: Long-term followup of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncol Group,” J Am Med Associat 1999;281:1623–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Minsky BD, Pajak TF, Ginsberg RJ, et al. Phase III trial of combined-modality therapy for esophageal cancer: highdose versus standard-dose radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yi-Feng Wu, Sung-Chao Chu, Bee-Song Chang, et al. Hematologic Markers as Prognostic Factors in Nonmetastatic Esophageal Cancer Patients under Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:1263050.doi: 10.1155/2019/1263050. eCollection 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gilda Varricchia, Maria Rosaria Galdieroa, Stefania Loffredo, et al. Eosinophils: the unsung heroes in cancer. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1393134.(14 pages). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ana Laura Saraiva, Fátima Carneiro. New insights into the role of tissue eosinophils in the progression of colorectal cancer: a literature review. Acta Med Port 2018;31:329–37. doi: 10.20344/amp.10112. Epub 2018 Jun 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fernandez-Acenero MJ, Galindo-Gallego M, Sanz J, et al. Prognostic influence of tumor-associated eosinophilic infiltrate in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2000;88:1544–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hu G, Wang S, Zhong K, et al. Tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia predicts favorable clinical outcome in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2020;20:454.Published 2020 May 20. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-06966-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Varricchi G, Galdiero MR, Loffredo S, et al. Eosinophils: the unsung heroes in cancer? Oncoimmunology 2017;7:e1393134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Iwasaki K, Torisu M, Fujimura T. Malignant tumor and eosinophils. I. Prognostic significance in gastric cancer. Cancer 1986;58:1321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cuschieri A, Talbot IC, Weeden S. Influence of pathological tumour variables on long-term survival in resectablegastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2002;86:674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Harbaum L, Pollheimer MJ, Kornprat P, et al. Peritumoraleosinophils predict recurrence in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol 2015;28:403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Prizment AE, Vierkant RA, Smyrk TC, et al. Tumor eosinophil infiltration and improved survival of colorectal cancer patients: Iowa Women's Health Study. Mod Pathol 2016;29:516–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pretlow TP, Keith EF, Cryar AK, et al. Eosinophil infiltration of human colonic carcinomas as a prognostic indicator. Cancer Res 1983;43:2997–3000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nielsen HJ, Hansen U, Christensen IJ, et al. Independent prognostic value of eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in colorectal cancer tissue. J Pathol 1999;189:487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fujii M, Yamashita T, Ishiguro R, et al. Signifi-cance of epidermal growth factor receptor and tumor associated tissue eosinophilia in the prognosis of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. AurisNasus Larynx 2002;29:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dorta RG, Landman G, Kowalski LP, et al. Tumour-associated tissue eosinophilia as a prognostic factor in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Histopathology 2002;41:152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jain M, Kasetty S, Sudheendra US, et al. Assessment of tissue eosinophilia as a prognosticator in oral epithelial dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma-an image analysis study. Patholog Res Int 2014;2014:507512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thompson AC, Bradley PJ, Griffin NR. Tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia and long-term prognosis for carcinoma of the larynx. Am J Surg 1994;168:469–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lucarini V, Ziccheddu G, Macchia I, et al. IL-33 restricts tumor growth and inhibits pulmonary metastasis in melanoma-bearing mice through eosinophils. Oncoimmunology 2017;6:e1317420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mattes J, Hulett M, Xie W, et al. Immunotherapy of cytotoxic T cell-resistant tumors by Thelper 2 cells: an eotaxin and STAT6-dependent process. J Exp Med 2003;197:387–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Carretero R, Sektioglu IM, Garbi N, et al. Eosinophils orchestrate cancer rejection by normalizing tumor vessels and enhancing infiltration of CD8 (C) T cells. Nat Immunol 2015;16:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yuling Zhang, Hongzheng Ren, Lu Wang, et al. Clinical impact of tumor-infiltrating inflammatory cells in primary small cell esophageal carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:9718–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Carretero R, Sektioglu IM, Garbi N, et al. Eosinophils orchestrate cancer rejection by normalizing tumor vessels and enhancing infiltration of CD8 (+) T cells. Nat Immunol 2015;16:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ishibashi S, Ohashi Y, Suzuki T, et al. Tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2006;26(2B):1419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ohashi Y, Ishibashi S, Suzuki T, et al. Significance of tumor associated tissue eosinophilia and other inflammatory cell infiltrate in early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2000;20(5A):3025–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu Y, Chen J, Shao N, et al. Clinical value of hematologic test in predicting tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Moreira A, Leisgang W, Schuler G, et al. Eosinophilic count as a biomarker for prognosis of melanoma patients and its importance in the response to immunotherapy. Immunotherapy 2017;9:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Onesti CE, Josse C, Poncin A, et al. Predictive and prognostic role of peripheral blood eosinophil count in triple-negative and hormone receptor-negative/HER2-positive breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment. Oncotarget 2018;9:33719–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tajima K, Yamakawa M, Inaba Y, et al. Cellular location of interleukin-5 expression in rectal carcinoma with eosinophilia. Hum. Pathol 1998;29:1024–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. JAMA 1999;281:1623–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, et al. Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Caineng Cao, Jingwei Luo, Li Gao, et al. Definitive radiotherapy for cervical esophageal cancer. Head Neck 2015;37:151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]