Abstract

This study was aimed to design the first dual-target small-molecule inhibitor co-targeting poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) and bromodomain containing protein 4 (BRD4), which had important cross relation in the global network of breast cancer, reflecting the synthetic lethal effect. A series of new BRD4 and PARP1 dual-target inhibitors were discovered and synthesized by fragment-based combinatorial screening and activity assays that together led to the chemical optimization. Among these compounds, 19d was selected and exhibited micromole enzymatic potencies against BRD4 and PARP1, respectively. Compound 19d was further shown to efficiently modulate the expression of BRD4 and PARP1. Subsequently, compound 19d was found to induce breast cancer cell apoptosis and stimulate cell cycle arrest at G1 phase. Following pharmacokinetic studies, compound 19d showed its antitumor activity in breast cancer susceptibility gene 1/2 (BRCA1/2) wild-type MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 xenograft models without apparent toxicity and loss of body weight. These results together demonstrated that a highly potent dual-targeted inhibitor was successfully synthesized and indicated that co-targeting of BRD4 and PARP1 based on the concept of synthetic lethality would be a promising therapeutic strategy for breast cancer.

KEY WORDS: BRD4, PARP1, Dual-target inhibitor, Synthetic lethality, Quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; BET, bromodomain and extra-terminal domain; BRCA1/2, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1/2; BRD4, bromodomain 4; CDK4/6, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6; DSB, DNA double-strand break; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; ER, estrogen receptor; ESI-HR-MS, high-resolution mass spectra; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I; HE, hematoxylin-eosin; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; HR, homologous recombination; HRD, homologous recombination deficiency; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NHEJ, nonhomologous end-joining; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; PI, propidium iodide; PK, pharmacokinetics; PPI, protein−protein interaction; SAR, structure–activity relationship; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; SOP, standard operation process; TCGA, the cancer genome atlas; TGI, tumor growth inhibition; TLC, thin-layer chromatography; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; TR-FRET, time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer.

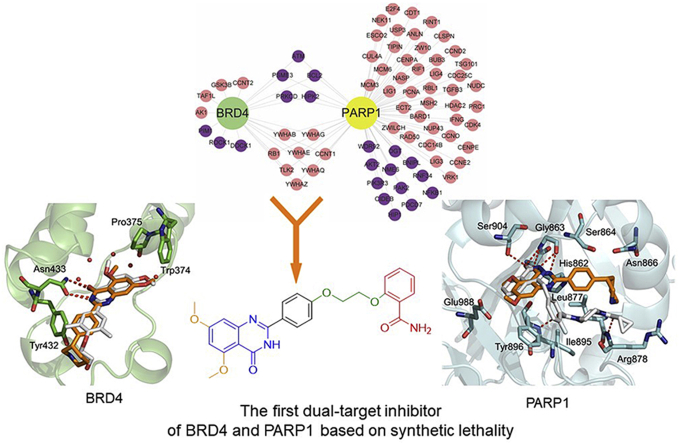

Graphical abstract

The first potential BRD4 and PARP1 inhibitors 19d named ADTL-BPI1901 was discovered and synthesized by fragment-based combinatorial screening and activity assays led to the three rounds of structural optimization. Preliminary structure−activity relationships, molecular modeling, pharmacokinetics and favorable in vivo antitumor efficacy of 19d were investigated.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a complex multigene disease and developed from the genetic defect or acquired DNA damage, and involves multiple cross-talks pathway, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is more likely to carry BRCA1/2 mutations, with high metastasis, recurrence rates and shorter overall survival rates1, 2, 3, 4. According to the statistics of international cancer research institute, breast cancer has become the highest incidence of cancer among women in the world5. Currently, the main treatment for BC patients is chemotherapy with small-molecule drugs in addition to radiotherapy and surgery6, 7, 8. As shown in Fig. 1, such as neratinib, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor; lapatinib, EGFR and receptor tyrosine-protein kinase ERBB-2 inhibitor; fulvestrant, estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist; exemestane, aromatase inhibitor; ribociclib and abemaciclib, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors9, 10, 11, 12, 13. These targeted therapy drugs have improved cancer treatment for many people in a certain period of time. However, to make further progress with genetically targeted cancer therapy, our ability has been limited. Although partial responses to targeted therapies in selected patient populations are common, converting those partial responses to durable complete responses will require combination regimens that have been challenging to define14,15. Until 2009, the first human clinical trial of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) inhibitor Olaparib confirmed the synthetic lethal effect of PARP1 inhibitor in the treatment of BRCA1/2-deficient breast cancer16. In the next 10 years, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the antitumor drugs based on the concept of synthetic lethal for the treatment of ovarian cancer and breast cancer, as well as a lot of clinical research on pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer. PARP1 inhibitors (Fig. 1) have become the first clinically designed drugs base on synthesize lethal, and show great potential17, 18, 19. Drug design method based on the concept of synthetic lethality may have broad potential to drive the discovery of the next wave of genetic cancer targets and ultimately the introduction of effective medicines that are still needed for most cancers20, 21, 22.

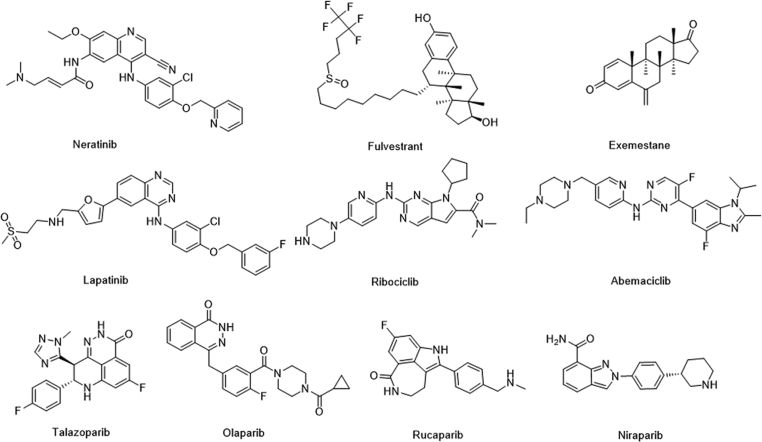

Figure 1.

Molecular drugs for breast cancer treatment and four approved PARP-1 inhibitors.

Synthetic lethality, initially described in drosophila as recessive lethality, is classically defined as the setting in which inactivation of either of two genes individually has little effect on cell viability but loss of function of both genes simultaneously leads to cell death23,24. In cancer, the concept of synthetic lethality has been extended to pairs of genes, in which inactivation of one by deletion or mutation and pharmacological inhibition of the other leads to death of cancer cells, whereas normal cells (which lack the fixed genetic alteration) are spared the effect of the drug25,26. Notably, PARP inhibitors based on this concept of synthetic lethality are related to DNA repair pathway and mainly used as drugs in cancer patients with BRCA1/2 mutations. Mechanically, BRCA1/2 play an important role in homologous recombination (HR) repair. For some tumor cells, BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation, resulting in the cells can not complete DNA repair well. At this time, if a DNA repair inhibitor is applied to tumor cells, it will produce a synthetic lethal effect to kill tumor cells27, 28, 29. Although this strategy is very effective, BRCA1/2 mutations account for only 2%–3% of all breast cancers30. To some extent, this situation limited the wider application of the strategy. Therefore, therapeutic strategies to sensitize BRCA1/2 wild-type tumors to PARP inhibitors remain to be fully explored31,32. The development of strategies to increase the duration of response of PARP inhibitor and expand the utility of PARP inhibitor to other HR deficient tumors is critical33,34.

Large-scale gene-knockout (using short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-based approaches) studies across many genetic contexts are now being used to map synthetic lethal interactions in human cancer cells35,36. A recent study found that BRD4 shRNA significantly elevated homologous recombination defects (HRD) scores in human THP-1 cells and in murine MLL-AF9/NrasG12D acute myeloid leukemia cells37. In the next in-depth study, the researcher found that BRD4 inhibitors could induce HRD by down regulating the expression of DNA double-stand break (DSB) resection protein C-terminal binding protein interacting protein (CtIP)38. Another study also found that knockdown of BRD4 expression by shRNA to the human, which contributed to decrease the expression of TOPBP1 and WEE1. Both TOPBP1 and WEE1 played critical role in DNA replication and DNA damage signaling39. In addition, there were also literature reported that BRD4 mediated the formation of oncogenic gene rearrangements and was critical for nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) repair of activation-induced cytidine deaminase and I-SceI-induced DNA breaks40,41. These results indicated that BRD4 played an important role in DNA repair pathway. The bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) protein BRD4 promoted gene transcription by RNA polymerase II, which could mediate signaling transduction to changes in gene regulatory networks42. Inhibition of BRD4 may affect DNA repair in more ways42,43. Encouraged by these results, we envisioned that the activity of PARP and BRD4 were inhibited simultaneously to form a synthetic lethal effect and sensitize BRCA1/2 wild-type cancer cells. Notably, some clinical studies also showed that combination therapy with PARP and BRD4 inhibitor was effective in the treatment of ovarian cancer44. Hence, we first identified the possible interaction between PARP and BRD4 in breast cancer by using the system biological network. Considering the advantages of dual-target design drug compared with combination drug45, 46, 47, 48, 49, then we rationally designed the first dual-inhibitor of BRD4 and PARP1 by fragment-based combinatorial screening50, 51, 52. Through chemical synthesis and structure–activity relationship (SAR) study, the candidate compound 19d, also named ADTL-BPI1901, was obtained and showed excellent inhibition activities against both targets and favorable in vivo antitumor efficacy in BRCA1/2 wild-type MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 xenograft models. The study demonstrated the therapeutic potential of 19d to target both BRD4 and PARP1, and 19d may serve as a candidate drug for future breast cancer therapy.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Bioinformatics analysis

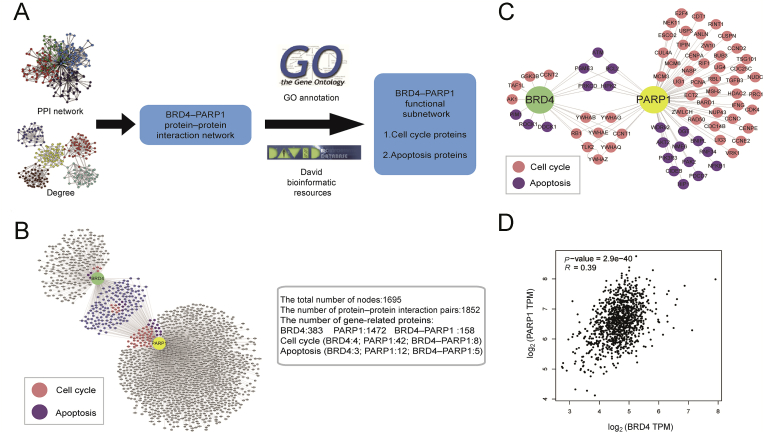

To explore further potential roles of BRD4 and PARP1 in BRCA development, protein−protein interaction (PPI) network was established. The BRD4- and PARP1-related proteins were extracted from the total network, and then were further modified by gene ontology and David bioinformatic resources (Fig. 2A). 383 proteins were identified to potentially interact with BRD4 and 1472 proteins were with PARP1 (Fig. 2B). Then, we identified a few of cell cycle and apoptotic hub proteins and relevant signaling pathways that found in the PPI network of BRD4−PARP1 (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Bioinformatics analysis. (A) Schematic illustration of the workflow of bioinformatics analyses of BRD4−PARP1. (B) Cluster analysis network diagram of BRD4 and PARP1 interaction proteins related to cell cycle, apoptosis. (C) Predicted BRD4- and PARP1-related proteins involved in the regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis, respectively. (D) Correlation between BRD4 and PARP1 in BRCA.

At last, we evaluated the correlation relation between BRD4 and PARP1 in BRCA, and found a significant positive correlation between two targets in BRCA from the transcriptome data of breast cancer in the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database (Fig. 2D). Overall, based on the analysis of existing bioinformatics data, the role of BRD4−PARP1 was associated with cell cycle and apoptosis in breast cancer, which had important cross relation in the global network of breast cancer.

2.2. Fragment-based combinatorial screening to identify lead compound

BRD4 contains two highly conserved N-terminal bromodomains (BD1 and BD2), which have similar sequences. BRD4(BD1) and BRD4(BD2) interact with acetylated chromatin as well as non-histone proteins to regulate transcription, DNA replication, cell cycle progression, and other cellular activities53. In the role of tumor, there have been some reports about the divergent function of BD1 and BD254, 55, 56, but they are still not very clear. Many of the reported BRD4 inhibitors showed highly potent BRD4 inhibitory activity, but due to the high structural homology of acetyl lysine-binding pockets of the BD1 and BD2 domains of BRD4, only a few of them exhibited excellent selectivity for BD1 or BD2 of BRD457,58. Most of BRD4 inhibitors showed equal affinity for the BD1 and BD2. At present, BRD4 inhibitors can be designed based on two bromine domains BD1 and BD2, respectively. For example, Zhang and Hoelder59,60 groups, respectively reported dual inhibitors of BRD4−PLK1 and BRD4−ALK. In their work, they focused on the BD1 domain to design the BRD4 inhibitors. And in another recent study, Liu groups61 reported that a dual-inhibitors of BRD4−HDAC was designed based on the BD2 domain of BRD4. In this study, we mainly designed BRD4 inhibitors based on BD2 domain.

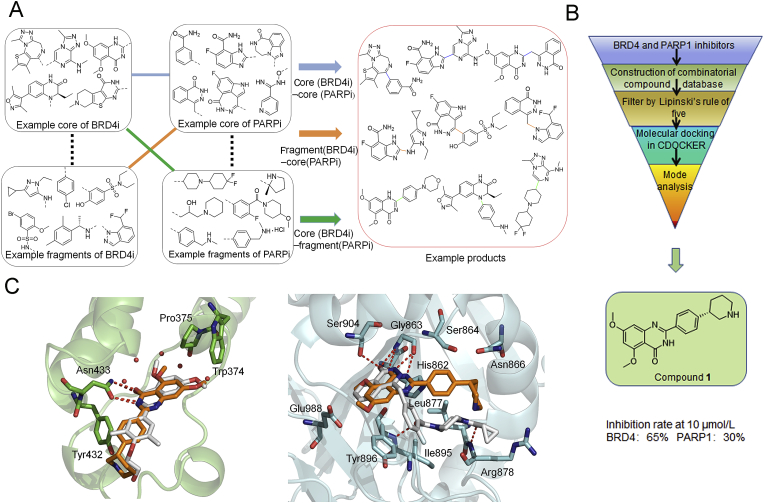

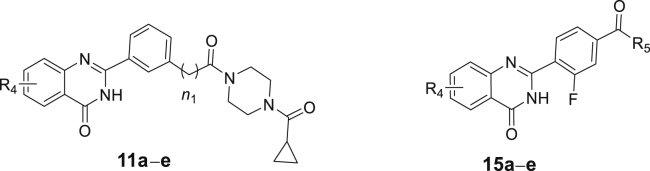

We firstly summarized the chemical structures of 22 PARP1 inhibitors and 71 BRD4 inhibitors, and split each of them into the core part and fragment part according to their binding modes and structure types (Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2). Subsequently, we constructed the combinatorial compound database in the design and enumerate module of Discovery Studio (version 3.5; San Diego, CA, USA) through three types of connection way: core (BRD4)‒core (PARP1), core (BRD4)‒fragment (PARP1) and core (PARP1)‒fragment (BRD4), and resulted in 1394, 1512, 1173 non-redundant compounds, respectively (Fig. 3A). Then, we performed a virtual screening workflow to filter the compound database. The initial combinatorial compound libraries were filtered by the Lipinski's rule of five. The CDOCKER protocol in Discovery Studio was applied to evaluate the binding modes and docking scores between those compounds and the two targets. Finally, based on the ranking of docking scores and the binding mode analysis, comparing to the complex RVX-208‒BRD4 and Olaparib‒PARP1, 20 potential dual-targeting inhibitors were picked out and tested by experimental assay in vitro. As a result, the lead compound 1 (docking score: BRD4 = −7.052 kcal/mol, PARP1 = −6.343 kcal/mol) was determined as the most suitable compound for the ligand binding pocket of BRD4 and PARP1 (Fig. 3B), which could be used for further structural modification.

Figure 3.

Design strategy of BRD4−PARP1 dual-targeted inhibitor. (A) Design of virtual composite compound library for BRD4 and PARP1. (B) Virtual screening protocol for the identification of the lead compound 1. (C) Predicted binding modes of compound 1 (brown) with BRD4 (green) [PDB ID: 5UOO] and PARP1 (grey) [PDB ID: 5DS3], compared to RVX-208 and Olaparib (white), respectively.

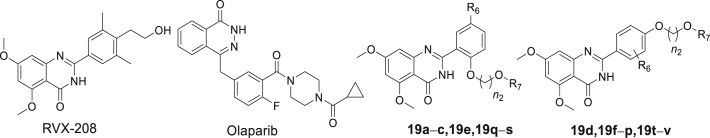

2.3. Synthesis of quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives

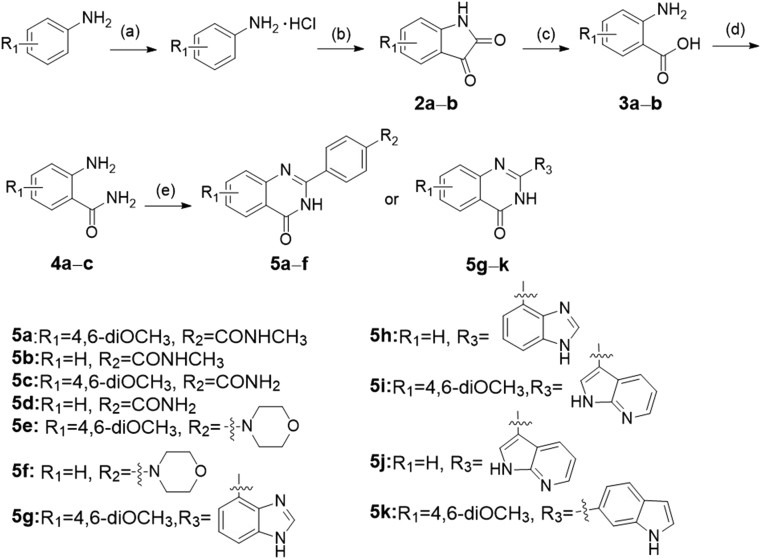

The synthetic routes of the all target compounds were shown in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Scheme 3, Scheme 4. Compounds 5a‒k were obtained as the procedure described in Scheme 1. Briefly, 3,5-dimethoxyaniline was first converted to the hydrochloride salt, and then the hydrochloride salt was reacted with oxalyl chloride under high temperature. After the simple treatment, the intermediate 4,6-dimethoxyindoline-2,3-dione named 2a was produced. The ring-opening of 2a was carried out under strong alkaline conditions, leading to intermediate 3a. The corresponding 3a was reacted with concentrated aqueous ammonia to produce key intermediate 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzamide (4a) in tetrahydrofuran. The synthesis route of intermediate 4c (2-amino-6-methoxybenzamide) was the same as 4a. Compound 4b named 2-aminobenzamide was purchased directly. Finally, intermediates 4a and 4b reacted with various aldehydes using p-toluenesulfonamide as a catalyst to give target compounds 5a‒k at high temperature for 16–20 h.

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of compounds 5a‒k. Reagents and conditions: (a) HCl/Et2O, overnight, r.t.; (b) (COCl)2, 160 °C, 2.5 h; (c) NaOH, H2O2, 70 °C, 0.8 h; (d) ammonium hydroxide, HOBt, EDCI, NMM, THF, overnight, r.t.; (e) benzaldehyde analogues, DMAC, PTSA, NaHSO3, 120 °C, 16–20 h.

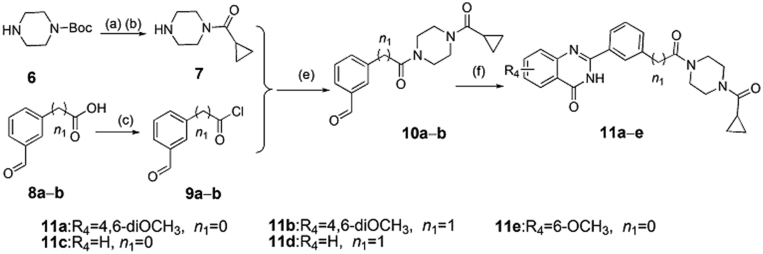

Scheme 2.

The synthesis of compounds 11a−e. Reagents and conditions: (a) cyclopropanecarbonyl chloride, Et3N, DCM, 0–25 °C, 5 h; (b) HCl/MeOH, 0–25 °C, 4–6 h; (c) thionyl chloride, toluene, 80 °C, 10 h; (e) Et3N, DCM, 0–20 °C, 3–5 h; (f) 2-aminobenzamide analogues, DMAC, PTSA, NaHSO3, 120 °C, 16–20 h.

Scheme 3.

The synthesis of compounds 15a‒e. Reagents and conditions: (a) thionyl chloride, toluene, 80 °C, 6 h; (b) 1-(cyclopropylcarbonyl)piperazine hydrochloride, or 3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine, Et3N, DCM, 0–20 °C, 6–8 h; (c) 2-aminobenzamide analogues, DMAC, PTSA, NaHSO3, 120 °C, 16–20 h.

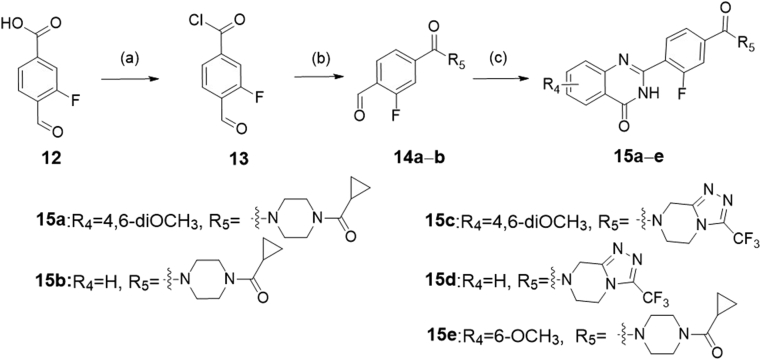

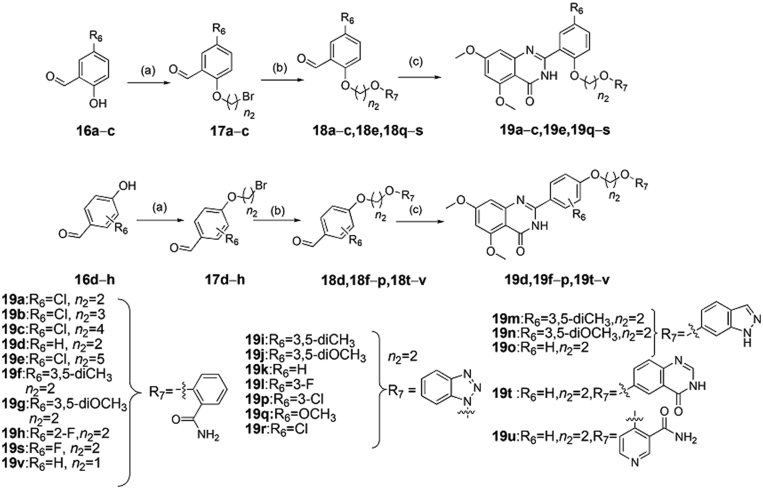

Scheme 4.

The synthesis of compounds 19a‒v. Reagents and conditions: (a) various dibromoalkanes, DMF, K2CO3, overnight, r.t.; (b) hydroxyl-substituted analogues, DMF, K2CO3, r.t., or 80 °C, 8 h; (c) 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzamide, DMAC, PTSA, NaHSO3, 120 °C, 16–20 h.

The target compounds 11a‒e and 15a‒e were synthesized according to the procedures in Scheme 2, Scheme 3, respectively. In Scheme 2, intermediate 7 was obtained by the reaction of N-Boc-piperazine with cyclopropyl acid chloride and N-Boc deprotection. Under the condition of heating, the carboxy analogs 8a and 8b were treated with thionyl chloride to produce the intermediates 9a and 9b. Then, the intermediate 7 reacted, respectively with the intermediates 9a and 9b to obtain the compounds 10a and 10b by triethylamine in dichloromethane. Finally, target compounds 11a‒e were obtained by the reaction of 2-aminobenzamide analogues (4a‒c) with intermediates (10a and 10b) at high temperature for 16–20 h. We also synthesized the target compounds 15a‒e in Scheme 3, and the synthetic route was similar with that of in Scheme 2.

The target compounds 19a‒v were synthesized according to the procedure showed in Scheme 4. Commercially available compounds 16a‒h reacted with different dibromoalkanes in N,N-dimethylformamide under basic condition of potassium carbonate to produce compounds 17a‒h, which next reacted with different hydroxyl-substituted compounds to give 18a‒v in similar alkaline condition, respectively. Finally, target compounds 19a‒v were obtained in dimethylacetamide by the reaction of 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzamide with 18a‒v at high temperature for 16–20 h, respectively.

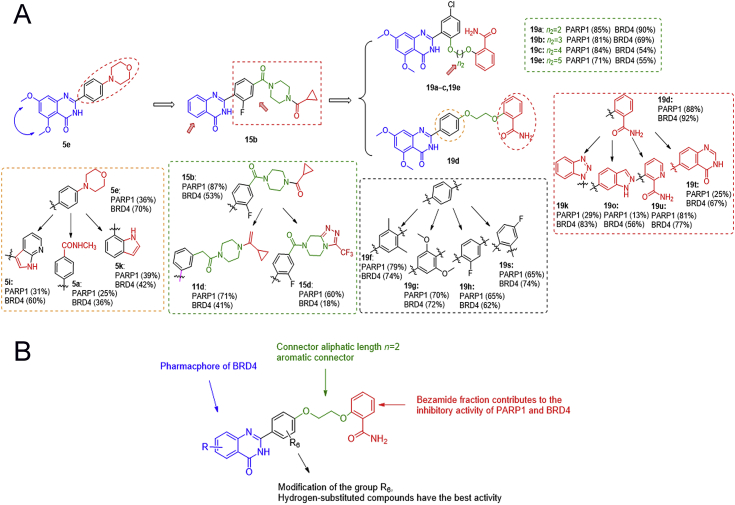

2.4. Structural optimization of the BRD4 and PARP1 inhibitors

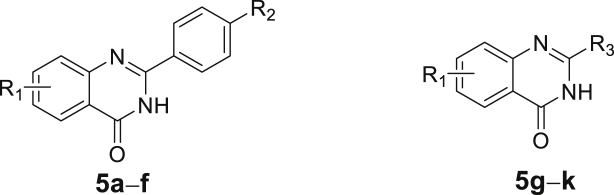

As predicted by docking analysis, compound 1 shared a similar binding mode with typical BRD4 inhibitor RVX-208 and interacted with BRD4 by a linear conformation (Fig. 3C). The carbonyl oxygen and nitrogen atom of the quinazolinone ring system displayed key hydrogen bonding interactions with amide group of Asn433, respectively. The terminal piperidine group was far from Tyr432, which had little effect on the overall activity. For the binding mode of compound 1 with PARP1, similarly, two hydrogen bonds were formed with the backbone atoms of Gly 863, but the terminal group of compound 1 did not completely occupy the entire channel. Moreover, compared to Olaparib, we also found that compound 1 lacked the key hydrogen bond with Ser904 at the core group, and with Arg878 and Tyr896 at the tail group (Fig. 3C). These may be important factors affecting the binding stability and affinities of compound 1 to PARP1. Indeed, lead compound 1 showed a good inhibition rate of BRD4 (up to 65% at 10 μmol/L) while the inhibition rate of PARP1 was only 30% at 10 μmol/L. Taking into account the presence of large hydrophobic cavity at the PARP1 surface region, the tail group of compound 1 should be further optimized to fit the binding pocket. The terminal piperidine group was far from Tyr432, which had littlee overall activity. In this context, we performed the first round of structural optimization by modifying the tail group of compound 1. The target compounds 5a‒k were first synthesized by introducing substitutions (R1 and R2) on the benzene ring and aromatic heterocycle effect on ths replacement (R3). These structures were supposed to form various interactions with the pocket of PARP1. The inhibition rate of compounds 5a‒k for BRD4 and PARP1 were determined at 1 and 10 μmol/L in Table 1, respectively. When R2 group was morpholine ring, the inhibition rate for BRD4 of compound 5e could reach to 70%. However, R3 group was replaced by benzimidazole, indole and azaindole (5g‒k), the inhibition rates for BRD4 were not further improved. These compounds still had poor inhibitory rate against PARP1 (only up to 39%). Moreover, we found that dimethoxy group might be the key group to inhibit BRD4, and this was similar with RVX-208. We observed that the R1 group was hydrogen-substituted, the inhibition rates of 5b, 5d, 5f, 5h and 5j were relatively low. While the R1 group was replaced by dimethoxy, the inhibition rates for BRD4 of compounds 5a, 5e, 5g and 5i were increased.

Table 1.

Inhibition rates of compounds 5a‒k against PARP1 and BRD4.

| No. | R1 | R2 | R3 | Inhibition rate (1 μmol/L/10 μmol/L, %)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1 (μmol/L) |

BRD4 (μmol/L) |

||||||||

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 | ||||||

| 5a | 4,6-diOCH3 | CONHCH3 | – | 4 | 25 | 1 | 36 | ||

| 5b | H | CONHCH3 | – | 0 | 15 | 0 | 22 | ||

| 5c | 4,6-diOCH3 | CONH2 | – | 0 | 2 | 1 | 18 | ||

| 5d | H | CONH2 | – | 0 | 1 | 2 | 19 | ||

| 5e | 4,6-diOCH3 |  |

– | 2 | 36 | 12 | 70 | ||

| 5f | H |  |

– | 0 | 29 | 12 | 55 | ||

| 5g | 4,6-diOCH3 | – |  |

9 | 34 | 3 | 13 | ||

| 5h | H | – |  |

3 | 10 | 0 | 11 | ||

| 5i | 4,6-diOCH3 | – |  |

8 | 31 | 7 | 60 | ||

| 5j | H | – |  |

7 | 28 | 6 | 26 | ||

| 5k | 4,6-diOCH3 | – |  |

6 | 39 | 8 | 42 | ||

‒Not applicable.

Each compound was tested in duplicate, the average value was obtained.

In order to improve the inhibition rate for PARP1, different moieties contained in reported potent PARP1 inhibitors were analyzed and chosen as the tail group. We found that Olaparib's tail had a bisamide structure, could interact with PARP1's Arg878 and Tyr869 to form two key hydrogen bonds. Thus, we performed the second round of structural optimization by introducing a set of similar structures as substituents attached to the benzene ring. Compounds 11a‒e and 15a‒e were synthesized, and their inhibition rates for BRD4 and PARP1 were tested. When introducing the structure of bisamide on the meta-position to the benzene ring, 11 series of compounds exhibited moderate inhibition rates against PARP1 and BRD4 at 10 μmol/L, respectively. When the structure of bisamide was introduced on the para-position of the benzene ring, and the fluorine atom was introduced at 2-position simultaneously, the inhibition rates of compound 15a were increased against PARP1 and BRD4, respectively. Similar trends were observed in the inhibition rates exhibited by other 15 series compounds. Fluorination of pharmaceutical compounds is a common tool to modulate their physiochemical properties62. As a consequence of the unique properties of fluorine, fluorine substitution can influence the potency, conformation, metabolism, membrane permeability of a molecule63,64. The fluorine atom at 2-position of the benzene ring may together contribute to the enhancement of the inhibition rate against BRD4 and PARP1. In addition, the inhibition rates of PARP1 could not be significantly increased by extending the structure size of bisamide on the meta-position of benzene ring (Table 2, 11a vs. 11c, 11b vs. 11d). Further research found that the substitution of R4 with hydrogen could obtain better inhibition rate for PARP1 (up to 87% at 10 μmol/L), but the inhibition rate for BRD4 was decreased by 15% (Table 2, 15b vs. 15a). Binding mode results displayed that the key interaction sites of compound 15b with PARP1 (Ser904, Gly863 and Arg878) were very similar with Olaparib (Supporting Information Fig. S2B). However, compared with RVX-208, there was only one hydrogen bond interaction between 15b and Cys429 of BRD4. In addition, the conformation of 15b also dramatically changed. These results verified again that dimethoxy group was an important group for inhibiting BRD4 activity inhibition. Based on the above analysis, we found that only the tail groups with appropriate size and length could contribute to the improvement of inhibition rate.

Table 2.

Inhibition rates of compounds 11a‒e and 15a‒e against PARP1 and BRD4.

| No. | R4 | R5 | n1 | Inhibition rate (1 μmol/L/10 μmol/L, %)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1 (μmol/L) |

BRD4 (μmol/L) |

||||||

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| 11a | 4,6-diOCH3 | – | 0 | 6 | 57 | 4 | 50 |

| 11b | H | – | 0 | 16 | 70 | 12 | 43 |

| 11c | 4,6-diOCH3 | – | 1 | 8 | 60 | 9 | 47 |

| 11d | H | – | 1 | 18 | 71 | 4 | 41 |

| 11e | 6-OCH3 | – | 0 | 4 | 46 | 8 | 30 |

| 15a | 4,6-diOCH3 |  |

– | 14 | 72 | 7 | 68 |

| 15b | H |  |

– | 6 | 87 | 4 | 53 |

| 15c | 4,6-diOCH3 |  |

– | 11 | 55 | 5 | 30 |

| 15d | H |  |

– | 13 | 60 | 3 | 18 |

| 15e | 6-OCH3 |  |

– | 7 | 56 | 9 | 39 |

‒Not applicable.

Each compound was tested in duplicate, the average value was obtained.

In view of the above observations on the SAR, we found that dimethoxy group was favorable to BRD4 inhibition activity, but unfavorable to PARP1 inhibition activity in a certain range of space. In order to find a better balance and produce better inhibitory activity on both BRD4 and PARP1, based on the structure of 5,7-dimethoxy-2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one, we further designed other tail structures that can promote the interaction with PARP1. Since the corresponding binding pocket in PARP1 could accommodate flexible linkers with appropriate length, we designed to retain one amide group and use more flexible linker groups to meet the spatial needs. As such, the third round of structural optimization was performed, and compounds 19a‒u were synthesized. The flexible alkyl chain was introduced by oxygen atoms into the ortho-position of the benzene ring, and the benzamide group as the monoamide group was attached to the other end of the alkyl chain (Table 3, 19a‒c and 19e). Compound 19a, with two carbon atoms as the alkyl chain, exhibited good inhibition rate for BRD4 and PARP1 at 10 μmol/L (90% and 85%). However, as the alkyl chain grows, we observed the inhibition rates for PARP1 of the compounds 19b, 19c and 19e were slightly reduced, while the inhibition rates of BRD4 were decreased significantly by up to 36%. Subsequently, we tried to introduce the alkyl chains with two carbon atoms that were introduced onto the para-position of the benzene ring (Table 3, 19d and 19f‒h). To our delight, compound 19d (non-substituents group on the benzene ring vs. 19f‒h) exhibited further enhanced inhibition rate against PARP1 and BRD4 with an inhibition rate of 88% and 92%, respectively. However, for compound 19v with shorter alkyl chains (n2 = 1), the inhibition rates against PARP1 and BRD4 were lower than that of 19d, which were 51% and 60%, respectively. Encouraged by excellent inhibitory activity of 19d, the more dominant skeletons were introduced to replace benzamide group, which were selected from highly potent PARP1 inhibitors (Table 3, 19i‒u). Unfortunately, no better result had been achieved. In these skeletons, we also investigated the effect of electronegativity of benzene ring on the activity (19i‒u). The results revealed that regardless of whether the electron-withdrawing group or the electron-donating group was introduced, they all showed poorer activity than non-substituents group on the benzene ring. Through the above repeated and detailed screening, we obtained the optimal compound 19d toward both targets.

Table 3.

Inhibition rates and in vitro anti-proliferative activity of compounds 19a‒v.

| No. | R6 | R7 | n2 | Inhibition rate (1 μmol/L/10 μmol/L, %)a |

Anti-proliferative activity (IC50, μmol/L)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1 (μmol/L) |

BRD4 (μmol/L) |

|||||||

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 | |||||

| RVX-208 | – | – | – | 1 | 4 | 20 | 60 | >30 |

| Olaparib | – | – | – | 100 | 100 | – | – | 1.1 ± 1.4 |

| 19a | Cl |  |

2 | 30 | 85 | 31 | 90 | 6.0 ± 0.9 |

| 19b | Cl |  |

3 | 35 | 81 | 3 | 69 | 10.9 ± 0.5 |

| 19c | Cl |  |

4 | 29 | 84 | 7 | 54 | 7.4 ± 1.8 |

| 19d | H |  |

2 | 37 | 88 | 69 | 92 | 3.4 ± 1.1 |

| 19e | Cl |  |

5 | 18 | 71 | 4 | 55 | 15.3 ± 3.6 |

| 19f | 3,5-diCH3 |  |

2 | 40 | 79 | 11 | 74 | 8.4 ± 1.3 |

| 19g | 3,5-diOCH3 |  |

2 | 25 | 70 | 15 | 72 | 5.7 ± 2.1 |

| 19h | 2-F |  |

2 | 31 | 65 | 12 | 62 | 11.8 ± 3.4 |

| 19i | 3,5-diCH3 |  |

2 | 11 | 18 | 18 | 61 | >30 |

| 19j | 3,5-diOCH3 |  |

2 | 6 | 18 | 12 | 64 | >30 |

| 19k | H |  |

2 | 7 | 29 | 13 | 83 | 22.9 ± 2.4 |

| 19l | 3-F |  |

2 | 1 | 14 | 29 | 80 | 23.7 ± 3.3 |

| 19m | 3,5-diCH3 |  |

2 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 46 | >30 |

| 19n | 3,5-diOCH3 |  |

2 | 9 | 16 | 14 | 45 | >30 |

| 19o | H |  |

2 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 56 | >30 |

| 19p | 3-Cl |  |

2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 44 | >30 |

| 19q | OCH3 |  |

2 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 80 | 24.2 ± 2.2 |

| 19r | Cl |  |

2 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 77 | >30 |

| 19s | F |  |

2 | 12 | 65 | 8 | 74 | 8.7 ± 5.2 |

| 19t | H |  |

2 | 1 | 25 | 9 | 67 | >30 |

| 19u | H |  |

2 | 36 | 81 | 6 | 77 | 6.7 ± 2.4 |

| 19v | H |  |

1 | 19 | 51 | 29 | 60 | – |

‒Not applicable or not test.

Each compound was tested in duplicate, the average value was obtained.

IC50 values were obtained with cell viability assay for 24 h.

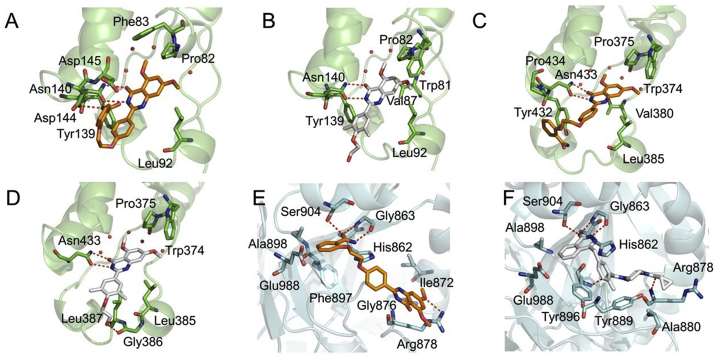

2.5. Inhibitory activities and docking models of compound 19d with BD1 and BD2 domains of BRD4 and PARP1

The inhibitory activities of 19d against BD1 and BD2 domains were tested as shown in Table 4 and Supporting Information Fig. S7. It can be seen that 19d had IC50 of 0.44 μmol/L for BD1 and IC50 of 0.379 μmol/L for BD2, which were quite close to the inhibitory activity of BRD4, suggesting that its inhibitory activity against BRD4 may be the comprehensive impact of targeting BD1 and BD2, while targeting BD2 is more important for its subtle selectivity for BD2 against BD1. Comparing to the inhibitory activities of RVX-208, it indicated that 19d achieved dual-targeting ability against BRD4 and PARP1 on the loss of its selectivity ability through three rounds of structural optimization. Next, compound 19d was further assessed in molecular docking to investigate its binding modes with BD1 and BD2 domains of BRD4 and PARP1. As shown in Fig. 4A‒D, Supporting Information Fig. S8A‒S8D and Table 5, the binding modes of core scaffold of compound 19d with BD1 and BD2 were quite similar to that of RVX-208. Except for the key hydrogen bonding interactions between quinazolinone ring and amide group of Asn140 in BD1 and Asn433 in BD2, the extended substitution of 19d with aliphatic chain linking benzamide strengthened the interaction with Asp144 and Asp145 in BD1, and the interaction with Tyr432 and Pro434 in BD2. As for the interaction with PARP1 (Fig. 4E and F, and Supporting Information Fig. S8E and S8F), the binding mode of compound 19d was also similar to that of Olaparib. 19d and Olaparib both formed three hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl group of Ser 904 and the amino group of Gly863, while 19d formed extra hydrophobic interactions with Ala880, Tyr889, Tyr896 and Ala898 (Table 5).

Table 4.

IC50 of 19d against BRD4 and PARP1 compared with RVX-208 and Olaparib.

| Molecular | IC50 (μmol/L) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRD4 | PARP1 | BRD4(BD1) | BRD4(BD2) | |

| Rvx-208 | 12.7 | – | 1.387 | 0.053 |

| Olaparib | – | 0.0013 | – | – |

| 19d | 0.4 | 4.6 | 0.44 | 0.379 |

‒Not applicable.

Figure 4.

Binding mode analysis of 19d, RVX-208 and Olaparib. (A) and (B) Binding mode of 19d and RVX-208 in the BD1 domain of BRD4. BRD4 (PDB code: 4MR4) was shown in green. (C) and (D) Binding mode of 19d and RVX-208 in the BD2 domain of BRD4. BRD4 (PDB code: 5UOO) was shown in green. (E) and (F) Binding mode of 19d and Olaparib in the active site of PARP1. PARP1 (PDB code: 5DS3) was shown in cyan. The carbon atoms of 19d were colored in orange, while RVX-208 and Olaparib were colored in white. The oxygen atoms were colored in red and nitrogen atoms in blue. Hydrogen bonds were indicated with dashed lines.

Table 5.

Comparison of key residues of 19d, RVX-208, Olaparib in protein BRD4 and PARP1 binding patterns.

| Molecular | Docking score (kcal/mol) |

Interactive residues (within 2.5 Å) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRD4(BD1) | BRD4(BD2) | PARP1 | BRD4(BD1) | BRD4(BD2) | PARP1 | ||

| Rvx-208 | ‒6.96 | ‒7.60 | ‒ | Trp81, Pro82, Val87, Leu92, Tyr139, Asn140 | Trp374, Pro375, Leu385, Gly386, Leu387, Asn433 | ‒ | |

| Olaparib | ‒ | ‒ | ‒10.94 | ‒ | ‒ | His862, Gly863, Arg878, Ala880, Tyr889, Tyr896, Ala898, Ser904, Glu988 | |

| 19d | ‒8.80 | ‒7.23 | ‒7.51 | Pro82, Phe83, Leu92, Tyr139, Asn140, Asp144, Asp145 | Trp374, Pro375, Tyr432, Asn433, His437, Glu438 | His862, Gly863, Arg878, Ala898, Ile872, Gly876, Phe897, Ser904, Glu988 | |

‒Not applicable.

2.6. SAR summary

Through the three rounds of structural optimization and inhibition rate evaluation for BRD4 and PARP1 of all compounds in vitro, the optimal compound 19d toward two targets was obtained (Fig. 5A and Supporting Information Fig. S2). Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 5B, the SAR was summarized as follows: (1) the benzamide group of the target compound as an effective group contributes to the inhibitory activity of PARP1 and BRD4; (2) proper linker length is very important. When the length of alkyl chain was two carbon atoms, the target compound possessed the most potent inhibitory activities against BRD4 and PARP1; (3) the dimethoxy group on the quinazolinone is an important group for inhibiting BRD4 activity; (4) different substituents of the R6 group on the benzene ring had different effects on the inhibitory activity of BRD4 and PARP1, and the hydrogen-substituted target compound had a favorable inhibitory activity against two targets.

Figure 5.

Structural optimization and discovery of the dual target inhibitors. (A) Target inhibitory activities evaluation in vitro guided optimization toward 19d. (B) SAR summary of BRD4 and PARP1 dual inhibitors.

2.7. In vitro anti-proliferation assay and western blot analysis of compound 19d

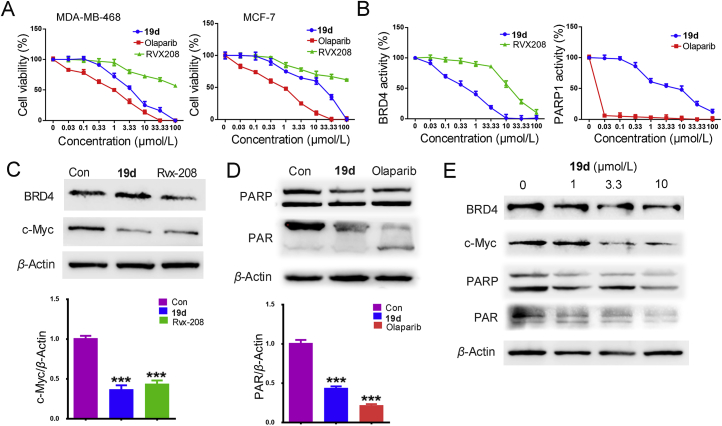

The cell-growth activity of 42 compounds was performed on human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 by using MTT assay, respectively. The 19d exhibited the highest cytotoxic effect in MDA-MB-468 cells and excellent inhibitory activities (Supporting Information Fig. S1 and Table 3). While the synthesis compounds showed weaken anticancer activity in MDA-MB-231 cells. Therefore, we discussed the anti-proliferation activity of 19d towards MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6A). For comparison, RVX-208 and Olaparib were used as standard drugs. The activity of 19d for BRD4 and PARP1 inhibition were summarized in Fig. 6B. The results showed that 19d exhibited significant inhibitory activities on BRD4 and moderate inhibitory activities on PARP1. As shown in Table 4, compound 19d exhibited its excellent inhibitory potency against BRD4 with an IC50 of 0.4 μmol/L, improved efficacy > 30-fold than RVX-208 (IC50 = 12.6 μmol/L). But the modest PARP inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 4.6 μmol/L was far less than Olaparib (IC50 = 1.3 nmol/L). However, compared with the anti-proliferative activity for MDA-MB-468 cells of Olaparib (IC50 = 1.1 ± 1.4 μmol/L), the compound 19d showed its parallel anti-proliferative activity toward MDA-MB-468 cells (IC50 = 3.4 ± 1.1 μmol/L). These results may be related to the synthetic lethality. Compound 19d might play a synthetic lethal role by targeting BRD4 and PARP1 together. Noteworthy, BRD4 regulates HR key effectors, and the present study confirmed that BET inhibition impaired HR-directed double strand breaks repair in BRCA1/2 wild-type TNBC cells65,66, which might confirm our speculation for these results to some extent. The potential synthetic lethal of compound 19d suggested that it was functionally inhibiting both BRD4 and PARP1.

Figure 6.

Identification of candidate compound 19d. (A) The anti-proliferation activity of 19d, RVX-208 and Olaparib towards MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 cells. (B) The inhibitory activity of 19d, RVX-208 and Olaparib for BRD4 and PARP1 were detected by activity assay in diverse concentrations. (C) MDA-MB-468 cells treated with 19d and RVX-208 for 24 h at 2 μmol/L, the expression of BRD4 and c-Myc were detected by Western blot. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (D) MDA-MB-468 cells treated with 19d and Olaparib for 24 h at 2 μmol/L, the expression of PARP and PAR were detected by Western blot. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (E) MDA-MB-468 cells treated with DMSO, 1, 3.3 and 10 μmol/L of 19d for 24 h, the expression levels of BRD4, c-Myc, PARP and PAR were detected by Western blot. β-Actin was used as a loading control. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with control group. Data are present as means ± SD, n = 3.

Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed that 19d showed higher c-Myc inhibition efficiency than RVX-208, and effective downregulation of PAR expression at 2 μmol/L (Fig. 6C and D). Notably, 19d decreased the expression of c-Myc and PAR in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6E). Consistent with our design strategy, these data showed that 19d was indeed an effective BRD4 and PARP1 dual inhibitor.

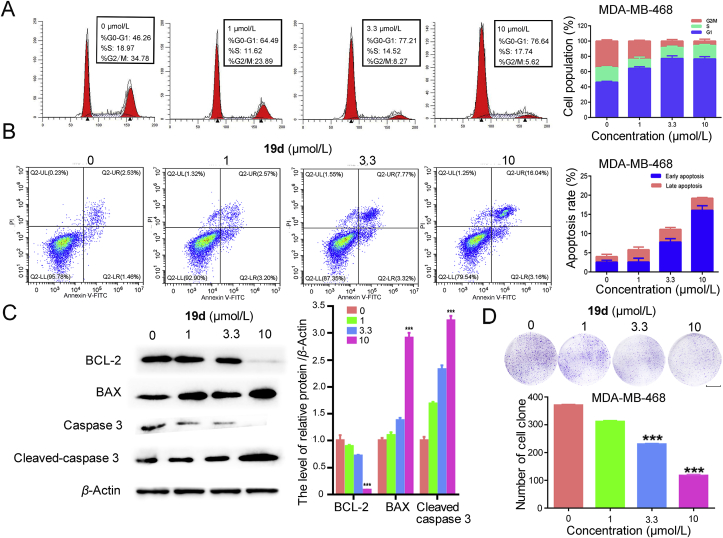

2.8. Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis assays

BRD4 and PARP1 were two regulators of cell proliferation by positive affect the cell cycle. To clarify the mechanism of the anti-proliferation effect of 19d, we firstly employed the cell cycle analysis. The MDA-MB-468 cells and MCF-7 cells were treated with different concentration of 19d. The percentage of cells in the G1, S, and G2/M phases was significantly changed in MDA-MB-468 cells. The percentage of MDA-MB-468 cells in G1 was remarkably increased and the percentage in G2/M phase significantly declined in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). However, there were no significant changes in 1 μmol/L 19d treatment during the G1 and G2/M phases compared to 3.3 and 10 μmol/L 19d treated MCF-7 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S6A). The results confirmed that the 19d interfered the cell cycle at the G1 phase, especially in MDA-MB-468 cells. Subsequently, we detected whether 19d could induce apoptosis. The results suggested that 19d induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). There were no significant changes in 19d treated MCF-7 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S6B). Next, Western blot analysis revealed that BCL-2 expression was remarkably downregulated, but BAX and the active form of caspase-3 expression were increased after 19d treatment (Fig. 7C). In the colony formation assay, compound 19d remarkably decreased the colony counts compared with the DMSO-treated control group (Fig. 7D). Taken together, these results indicated that 19d interfered the cell cycle arrest at G1 phase, suppressed cloning formation, and promoted apoptosis in MDA-MB-468 cells. However, it only showed slight activity on MCF-7 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S6). These results indicated that 19d was more effective on triple negative breast cancer.

Figure 7.

The mechanism of 19d-induced MDA-MB-468 cells death. (A) Cell cycle distribution of MDA-MB-468 cells was measured by flow cytometry using propidium iodide (PI) staining. (B) Apoptosis rates of MDA-MB-468 cells were detected by Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC)/PI staining after treatment with 19d. (C) After DMSO, 1, 3.3 and 10 μmol/L of 19d treatment in MDA-MB-468 cells, the expression levels of BCL-2, BAX and caspase 3 were determined by Western blot analysis. β-Actin was measured as loading control. (D) Colony formation assay was used to detect the proliferation ability in MDA-MB-468 cells after treatment of compound 19d. Scale bar: 10 mm. The statistics of the colony counts. ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with control group. Data are present as means ± SD, n = 3.

2.9. Pharmacokinetics (PK) profiles of compound 19d

Based on its closely matched BRD4/PARP1 inhibitory activity, potent anti-proliferative and proapoptotic capacities, compound 19d was progressed into an in vivo pharmacokinetic study. As shown in Table 6, plasma PK after 10 mg/kg oral administration of compound 19d to Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats was characterized. Compound 19d showed a good elimination half-life (t1/2) of 3.1 h with an AUC0−∞ of 144.7 h·ng/mL. The oral maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) was 26.65 ng/mL, Tmax was 1.58 h, and the mean residence time (MRT) was 5.35 h. These favorable pharmacokinetic properties of compound 19d apprehended its suitability for using as oral candidate.

Table 6.

PK profiles of compound 19d in SD rats (n = 3).

| Parameter | Ratap.o. (10 mg/kg) |

|---|---|

| t1/2 (h) | 3.10 ± 0.12 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.58 ± 0.35 |

| MRT0−∞ (h) | 5.35 ± 0.44 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 26.65 ± 3.66 |

| AUC0−t (h·ng/mL) | 114.43 ± 15.81 |

| AUC0−∞ (h·ng/mL) | 144.72 ± 25.51 |

Data are present as means ± SD, n = 3.

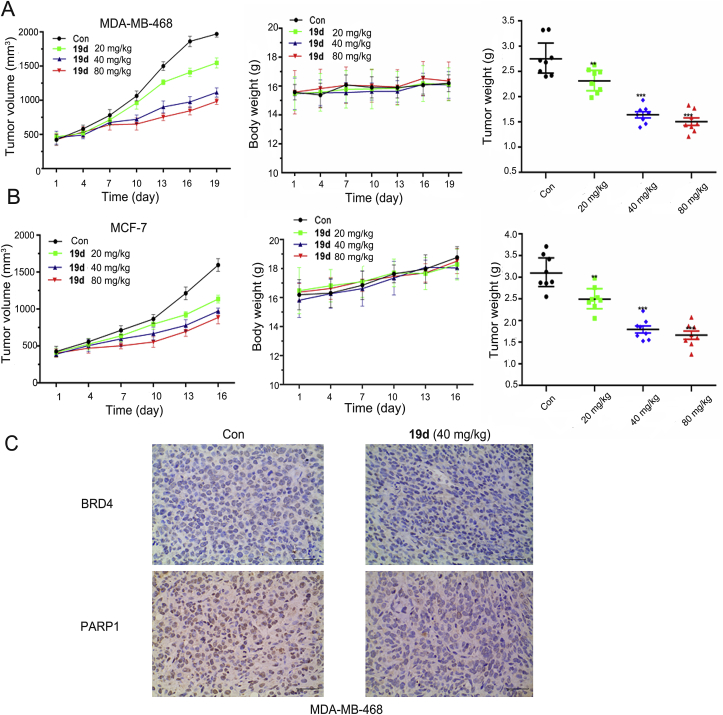

2.10. In vivo xenograft model experiments of compound 19d

Encouraged by the excellent potency in vitro as well as the acceptable PK profiles, 19d was further progressed into in vivo antitumor activity studies. In the MDA-MB-468 breast cancer xenograft model, oral doses of mice with 20, 40 and 80 mg/kg of 19d were chose based on the preliminary experiment and other previous studies67, 68, 69, 70, which achieved a dose-dependent tumor growth inhibition (TGI) effect. Medium dose and high dose groups showed similar inhibitory effects, with a TGI of 55.3% for 80 mg/kg. In this model, slight body weight change and no death of mice were observed during the treatment period. These results indicated that 19d exhibited potent antitumor effect without significant toxicity (Fig. 8A). To deep validate its dual antitumor mechanism, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed and showed that the expression levels of BRD4 and PARP1 were effectively suppressed in tumor tissues of the 19d 40 mg/kg treatment groups compared with the control group (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

In vivo antitumor efficacy of compound 19d in the MDA-MB-468 tumor xenograft model and the MCF-7 tumor xenograft model. (A) Tumor volume changes, average body weights and tumor weights following the treatment of 19d at oral doses of 20, 40 and 80 mg/kg in the MDA-MB-468 tumor xenograft model. (B) Tumor volume changes, average body weight and tumor weight following the treatment of 19d at oral doses of 20, 40 and 80 mg/kg in the MCF-7 tumor xenograft model. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of PARP1 and BRD4 in the MDA-MB-468 tumor tissues from 40 mg/kg of 19d-treated mice and vehicle groups (200 ×), respectively.

Further, the inhibition effect in MCF-7 breast cancer xenograft model was also evaluated. As shown, a similar TGI rate of 48.3% was observed in 80 mg/kg treatment group, and with slightly body weight increase in all the groups, indicating no apparent toxicity of all the dosages used here (Fig. 8B). In the IHC staining assay, the expression levels of BRD4 and PARP1 were slightly downregulated in the tumor tissues of the 19d treatment groups (Supporting Information Fig. S3). In addition, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) histology study in the major organs (heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney) of all the groups was conducted after 19d treatment (Supporting Information Figs. S4 and S5), and 19d showed no visible histological changed, indicating no apparent toxicity of 19d.

3. Conclusions

In summary, as a result of cross roles between BRD4 and PARP1 of the synthetic lethality mechanism, the important relation of them was further identified through the global PPI network in breast cancer. Therefore, we performed a virtual screening workflow to filter the compounds and got the lead compound 1 based on reported BRD4 and PARP1 inhibitors, the optimal compound 19d (named ADTL-BPI1901) was obtained and both exhibited potential enzymatic potencies against BRD4 and PARP1 through the three rounds of structural optimization. Further experiments demonstrated that 19d efficiently modulated the expression of BRD4 and PARP1. Compound 19d could induce breast cancer cell apoptosis and stimulated cell cycle arrests at G1 phase. Following PK studies, 19d showed its excellent antitumor activity in BRCA1/2 wild-type MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 xenograft models without causing remarkable loss of body weight and toxicity. Overall, the superior inhibition effect of compound 19d was systemically investigated and validated via in vitro and in vivo experiments. As the first potent dual-target inhibitor of BRD4 and PARP1 based on the concept of synthetic lethality, which shows favorable safety profiles that represents a promising candidate small-molecule drug for the future treatment of breast cancer.

4. Experimental

4.1. General methods of chemistry

All anhydrous solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. Evaporation of solvent was carried out by using a rotary evaporator (N-1100, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan) under reduced pressure. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 400 and 100 MHz by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (BrukerAV III-400, Karlsruhe, Germany), respectively. The chemical shifts were reported by using TMS as an internal standard and CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 as solvents. The isolation of compounds was carried out on silica gel (300–400 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Ltd., Qingdao, China). The progress of the reaction was detected by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel plates (silica gel 60 F254, Qingdao Marine Chemical Ltd, Qingdao, China). High-resolution mass spectra (ESI-HR-MS) data were recorded on a commercial apparatus, and methanol was used to dissolve the sample. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed by Wates e2695 (Shanghai, China) with Thermo C18-WR column (5.0 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm). HPLC conditions: liquid phase MeOH/H2O at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. All chemical structures were performed by ChemBioDraw software (version 14.0).

4.2. General synthetic information of target compounds

4.2.1. Preparation of compound 2a: 4,6-dimethoxyindoline-2,3-dione

3,5-Dimethoxyaniline (6.0 g, 38.2 mmol) was dissolved in ether (80 mL) and stirred at 0 °C. Saturated hydrochloric acid/ether solutions (15 mL) was bubbled into the reaction mixture for 20 min. The reaction mixture was removed to room temperature for 4 h and then filtered; the residue was washed with cooled ethyl acetate and dried in vacuo to give the corresponding hydrochloride salt (8 g, 98%). The hydrochloride salt of aniline 1 (3.5 g, 18.45 mmol) was dissolved in oxalyl chloride (5.3 mL), and the reaction mixture was heated to 170 °C for 2.5 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was diluted with MeOH (15 mL) at 0 °C and then heated to reflux for 1 h. The reaction mixture was hot filtered, and the precipitate was washed with MeOH to give compound 2a (2.9 g, 52%–69% yield) which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 10.92 (1H, brs), 6.17 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz), 6.02 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz), 3.88 (3H, s), 3.87 (3H, s).

4.2.2. Preparation of compound 3a: 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzoic acid

A solution of compound 2a in NaOH (33% in water, 19 mL) was heated to 70 °C. H2O2 (30% in water, 4.7 mL) was added to the solution dropwise. The mixture was maintained at 70 °C for 50 min. Saturated Na2S2O3 solution (18 mL) was added to the above mixture at 10 °C. The reaction mixture was adjusted to pH = 8 with HCl and then to pH = 5 with acetic acid. The precipitate that formed was collected, washed with water, and dried to give the title compound 3a (1.2 g, 24%–33% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ (ppm): 11.05 (1H, s), 6.43 (2H, s), 5.82 (2H, s), 3.95 (3H, s), 3.78 (3H, s).

4.2.3. Preparation of compound 4a: 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzamide

A mixture of EDCI (0.75 g, 3.8 mmol), HOBt (0.50 g, 3.8 mmol), and NMM (0.38 g, 3.8 mmol) were added to a solution of 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzoic acid (0.50 g, 2.55 mmol) in THF (15 mL). The mixture was stirred for 10 min, and then ammonium hydroxide (50% v/v aqueous solution) was bubbled through at room temperature, stirred overnight. Water was added (5 mL), and the aqueous layer was extracted with DCM (3 × 25 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with water (3 × 25 mL), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (DCM/MeOH = 80:1) to give the title compound 4a (0.43 g, 84% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 7.45 (1H, s), 7.01 (1H, s), 6.89 (2H, s), 5.88 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 5.76 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 3.76 (3H, s), 3.68 (3H, s). The synthetic route of compound 4c named 2-amino-6-methoxybenzamide was the same as that of compound 4a.

4.2.4. Preparation of target compounds 5a‒f and 5g‒k

2-Aminobenzamide analogues (4a and 4b, 0.86 mmol, 1 equiv.) and benzaldehyde analogues (0.86 mmol, 1 equiv.) were dissolved in DMAc (12 mL) and treated with sodium hydrogen sulfite (1.03 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and PTSA (0.21 mmol, 0.24 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 16–20 h. Water (80 mL) was added to the reaction, and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration. Purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 40:1–20:1) gave final compounds 5a‒k (37%–61% yield).

4.2.4.1. 4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)-N-methylbenzamide (5a)

Light yellow solid, Yield 56%. m.p. 221–224 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.56 (1H, brs), 10.20 (1H, s), 8.13 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.71 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s), 2.09 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 169.2, 164.7, 161.4, 160.2, 153.6, 152.8, 142.6, 128.9, 126.9, 118.8, 105.1, 101.6, 97.9, 56.4, 56.0, 24.6. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C18H18N3O4 [M+H]+: m/z 340.1297, Found 340.1294.

4.2.4.2. N-Methyl-4-(4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)benzamide (5b)

Off-white solid, Yield 48%. m.p. 233–235 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.39 (1H, brs), 10.22 (1H, s), 8.17–8.13 (3H, m), 7.84–7.80 (1H, m), 7.75–7.70 (3H, m), 7.51–7.47 (1H, dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 7.2 Hz), 2.09 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 169.2, 162.7, 152.3, 149.3, 142.6, 135.0, 128.9, 128.9, 127.8, 127.2, 126.7, 126.3, 121.2, 118.8, 118.7, 24.8. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C16H14N3O2 [M+H]+: m/z 280.1086, Found 280.1088.

4.2.4.3. 4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)benzamide (5c)

Light yellow solid, Yield 56%. m.p. 201–203 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.11 (1H, brs), 8.23 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 8.00 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.56 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.90 (3H, s), 3.86 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.8, 164.7, 161.5 (2C), 159.2, 153.4, 152.1, 143.7, 123.5, 122.2, 105.4, 102.0, 101.9, 98.2 (2C), 56.48, 56.15. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C17H16N3O4 [M+H]+: m/z 326.1141, Found 326.1137.

4.2.4.4. 4-(4-Oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)benzamide (5d)

Off-white solid, Yield 49%. m.p. 235–237 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.61 (1H, brs), 8.27 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.18 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.04 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.88–7.84 (1H, m), 7.57–7.53 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 167.6, 162.6, 152.1, 149.0, 137.0, 135.5, 135.1, 128.2, 128.1 (3C), 128.0, 127.3, 126.3, 121.6. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C15H12N3O2 [M+H]+: m/z 266.0930, Found 266.0933.

4.2.4.5. 5,7-Dimethoxy-2-(4-morpholinophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (5e)

Off-white solid, Yield 43%. m.p. 188–190 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ (ppm): 9.46 (1H, brs), 7.93 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 6.62 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.38 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 3.97 (3H, s), 3.92 (3H, s), 3.39–3.36 (4H, m), 2.07–2.03 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.6 (2C), 161.4 (2C), 160.4, 153.4, 150.2, 129.4 (2C), 111.5 (2C), 104.6, 100.9, 97.2, 56.3, 56.0, 47.7 (2C), 25.4 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C20H22N3O4 [M+H]+: m/z 368.1610, Found 368.1608.

4.2.4.6. 2-(4-Morpholinophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (5f)

Off-white solid, Yield 49%. m.p. 195–197 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ (ppm): 9.91 (1H, brs), 8.27 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.98 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.74–7.72 (2H, m), 7.41–7.37 (1H, m), 6.64 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 3.40–3.37 (4H, m), 2.07–2.04 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 162.9, 152.8, 150.1, 149.8, 134.8, 129.4 (2C), 127.4 (2C), 126.2, 125.7, 120.7, 118.6, 111.6, 47.7 (2C), 25.4 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C18H18N3O2 [M+H]+: m/z 308.1399, Found 308.1398.

4.2.4.7. 2-(1H-Indol-6-yl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (5g)

Light yellow solid, Yield 36%. m.p. 198–200 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.93 (1H, brs), 11.45 (1H, brs), 8.29 (1H, s), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.63 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.54 (1H, t, J = 2.5 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.1 Hz), 6.51–6.50 (2H, m), 3.90 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.7, 161.5, 160.4, 154.6, 153.8, 135.9, 130.6, 128.9, 125.3, 120.2, 118.8, 112.1, 105.0, 101.8, 101.5, 97.7, 56.4, 56.0. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C18H16N3O3 [M+H]+: m/z 323.1144, Found 322.1135.

4.2.4.8. 2-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazole-7-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (5h)

Off-white solid, Yield 35%. m.p. 174–176 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 13.68 (1H, brs), 13.21 (1H, brs), 8.66 (1H, s), 8.42 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 8.19 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.86–7.78 (3H, m), 7.56–7.47 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 161.4, 151.6, 149.5, 143.8, 141.0, 135.1, 129.7, 128.0, 126.9, 126.4, 126.0, 123.4, 121.8, 120.2, 116.4. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C15H11N4O [M+H]+: m/z 263.0933, Found 263.0930.

4.2.4.9. 5,7-Dimethoxy-2-(1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-3-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (5i)

Light white solid, Yield 51%. m.p. 185–189 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 13.16 (1H, brs), 9.04 (1H, s), 8.80 (1H, d, J = 5.5 Hz), 8.62 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.78–7.74 (1H, m), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.95 (3H, s), 3.87 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 165.0, 161.6, 159.0, 151.8, 149.7, 139.6, 136.8, 132.6, 129.8, 127.4119.2, 104.6, 104.0, 100.8, 97.8, 56.5, 56.2. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C17H15N4O3 [M+H]+: m/z 323.1144, Found 323.1140.

4.2.4.10. 2-(1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-3-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (5j)

Off-white solid, Yield 44%. m.p. 169–171 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.60 (1H, brs), 12.38 (1H, brs), 8.60–8.57 (2H, m), 8.10 (2H, dd, J = 6.7 Hz, 7.1 Hz), 7.80–7.78 (1H, m), 7.65 (1H, d, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.44–7.37 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 161.2, 150.3, 150.1, 143.9, 143.3, 135.0, 132.7, 129.9, 127.0, 126.5, 125.7, 121.6, 121.1, 118.3, 106.9. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C15H11N4O [M+H]+: m/z 263.0933, Found 263.0931.

4.2.4.11. 2-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazole-7-yl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (5k)

Light yellow solid, Yield 32%. m.p. 189–191 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 13.16 (2H, brs), 8.62 (1H, s), 8.34–8.33 (1H, m), 7.84 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.45–7.44 (1H, m), 6.81 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz), 6.56 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz), 3.92 (3H, s), 3.86 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 165.0, 164.7, 161.5, 159.3, 153.4, 152.1, 143.7, 123.5, 122.2, 121.2, 117.8, 113.5, 105.4, 101.9, 98.2, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C17H15N4O3 [M+H]+: m/z 322.1192, Found 322.1190.

4.2.5. Preparation of compound 7

N-Boc-Piperazine (1.82 g, 9.77 mmol) was added to a 250 mL three-necked flask with mechanical stirring and a thermometer. Triethylamine (1.48 g, 14.66 mmol), dichloromethane (40 mL), cooled to 0 °C, cyclopropanecarbonyl chloride (1.12 g, 10.75 mmol) was slowly added dropwise, and the temperature was controlled from 0 to 5 °C. After the completion of the dropwise addition, the reaction was carried out for 3 h at 10–25 °C. And then added 50 mL of water, added sodium carbonate to adjust pH = 8–9, separated the liquid, collected the organic phase, added 100 mL of water phase, and extracted once with dichloromethane. The methylene chloride phases were combined, washed once with 0.05 mol/L diluted hydrochloric acid (10 mL), and once with 50 mL of water. The combined organic were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to give the last crude product 2.1 g of 4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-N-Boc (Yield 82%), then 4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-N-Boc (2.1 g, 8.2 mmol) was added to saturated methanol hydrochloride solution (35 mL) at 0 °C and the solution was stirred for 15 min The mixture was allowed to reach room temperature, and stirred for 4–6 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the oily residue was diluted with water and alkalified with 1 mol/L NaOH to pH = 12, extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated to give the cyclopropyl (piperazin-1-yl)methanone (compound 7), which was used for reduction without further purification (yield 94%).

4.2.6. Preparation of compounds 10a and 10b

A mixture of 3-formylbenzoic acid analogue (10 mmol, 1 equiv.), thionyl chloride (12 mmol, 2.2 equiv.), and dimethylformamide (2 mL), in toluene (50 mL) was slowly warmed to 80 °C and stirred at that temperature for 3 h. The toluene was eliminated in the rotary evaporator to get 3-formylbenzoyl analogues (9a and 9b) used in the next step (yield 87%–90%).

Cyclopropyl (piperazin-1-yl)methanone (5.3 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL). Triethylamine (15.9 mmol, 3 equiv.) was added and the solution was cooled at 0 °C. 3-Formylbenzoyl chloride analogue (5.3 mmol, 1 equiv., diluted with 5 mL DCM) was added dropwise and then the reaction was stirred to room temperature. After 3 h, water and DCM were added, the phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice more with DCM. The combined organics were washed with brine, dried over sodium sulfate, filtered and evaporated to a white solid. And then purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (ethyl acetate/petroleum ether = 2:1) to give compounds 10a and 10b as a white solid (yield 69%–73%).

4.2.7. Preparation of target compounds11a‒e

2-Aminobenzamide analogues (4a‒c, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) and compound intermediates (10a and b, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) were dissolved in DMAc (10.0 mL) and treated with sodium hydrogen sulfite (0.74 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and PTSA (0.15 mmol, 0.24 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 16–20 h. Water (80 mL) was added to the reaction, and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration, purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 40:1–20:1) gave final compounds 11a‒e (35%–51% yield), respectively.

4.2.7.1. 2-(3-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (11a)

Yellow solid, Yield 35%. m.p. 260–262 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.12 (1H, brs), 8.25–8.20 (2H, m), 7.62–7.61 (2H, m), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.56 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.86 (3H, s), 3.71–3.41 (8H, m), 1.98–1.96 (1H, m), 0.75–0.71 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 168.1, 164.8, 161.6, 159.5, 159.1, 153.2, 150.5, 132.5, 130.4, 122.6, 117.1, 116.8, 105.4, 101.9, 98.7, 56.5, 56.1, 53.5, 52.8, 45.1, 42.1 (2C), 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C25H27N4O5 [M+H]+: m/z 463.1981, Found 463.1980.

4.2.7.2. 2-(3-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (11b)

Off-white solid, Yield 51%. m.p. 222–224 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.61 (1H, brs), 8.27 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.22 (1H, s), 8.17 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.86–7.84 (1H, m), 7.77 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 4.5 Hz), 7.54 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.73–3.52 (8H, m), 1.98–1.96 (1H, m), 0.76–0.72 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 169.0, 162.6, 152.1, 149.0, 136.6, 135.1, 133.4, 130.2, 129.4, 129.2, 127.9, 127.2, 126.7, 126.3, 121.5, 53.5, 52.8, 45.1, 42.1, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C23H23N4O3 [M+H]+: m/z 403.1770, Found 403.1771.

4.2.7.3. 2-(4-((4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)phenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (11c)

Off-white solid, Yield 45%. m.p. 230–232 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.00 (1H, brs), 8.14 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s), 3.68 (2H, brs), 3.47 (2H, brs), 2.41–2.34 (4H, m), 1.98–1.91 (1H, m), 0.71–0.67 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 164.7, 161.4, 160.2, 153.5, 153.1, 142.1, 131.5, 129.3, 128.0 (2C), 126.0, 105.2, 101.9, 101.7, 98.1, 61.8, 56.4, 56.1, 53.5, 52.8, 45.3, 42.1, 10.7, 7.4 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C25H29N4O4 [M+H]+: m/z 449.2189, Found 449.2191.

4.2.7.4. 2-(4-((4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl)methyl)phenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (11d)

Off-white solid, Yield 44%. m.p. 220–222 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.49 (1H, brs), 8.17–8.15 (3H, m), 7.84 (1H, dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.3 Hz), 7.76 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.49 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 3.75 (2H, s), 3.71–3.51 (8H, m), 1.96–1.93 (1H, m), 0.72–0.67 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 162.7, 152.6, 149.2, 142.1, 135.1, 131.9, 130.0, 129.4, 128.1 (2C), 127.9 (2C), 127.8, 126.9, 126.3, 121.4, 61.8, 52.8, 45.3, 42.0, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C23H25N4O2 [M+H]+: m/z 417.1927, Found 417.1928.

4.2.7.5. 2-(3-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-5-methoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (11e)

Off-white solid, Yield 48%. m.p. 218–220 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.25 (1H, brs), 8.26–8.24 (1H, m), 8.20 (1H, s), 7.72 (1H, t, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.62 (2H, d, J = 4.7 Hz), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.70–3.56 (8H, m), 1.98 (1H, s), 0.76–0.72 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 169.0, 160.7, 160.2, 160.2, 152.3, 151.5, 136.6, 135.3, 133.0, 130.2, 129.3 (2C), 126.6, 119.9, 111.1, 108.9, 56.4, 52.8, 45.1, 42.2, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C24H25N4O4 [M+H]+: m/z 433.1876, Found 433.1877.

4.2.8. Preparation of compounds 14a and 14b

A mixture of 3-fluoro-4-formylbenzoic acid (10 mmol, 1 equiv.), thionyl chloride (12 mmol, 2.2 equiv.), and DMF (2 mL), in toluene (50 mL) was slowly warmed to 80 °C, and stirred at that temperature for 4 h. The toluene was eliminated in the rotary evaporator to get 3-fluoro-4-formylbenzoyl chloride (compound 13) used in the next step as such (yield 73%).

3-(Trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine hydrochloride (5.3 mmol, 1 equiv.) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL), triethylamine (15.9 mmol, 3 equiv.) was added and the solution was cooled at 0 °C. 3-Fluoro-4-formylbenzoyl chloride (5.3 mmol, 1 equiv., diluted with 5 mL DCM) was added dropwise and then the reaction was stirred to room temperature. After 4 h, water and DCM were added, the phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted twice more with DCM. The combined organics were washed with brine, dried over sodium sulfate, filtered and evaporated to a white solid. And then purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (ethyl acetate/petroleum ether = 1:1) to give compound 14a named 4-(4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-2-fluorobenzaldehyde as a white solid (yield 78%).

The synthetic route of compound 14b named 2-fluoro-4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl)benzaldehyde was the same as that of compound 14a (yield 64%).

4.2.9. Preparation of target compounds 15a‒e

2-Aminobenzamide analogues (0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) and intermediates (14a and 14b, 0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) were dissolved in DMAc (8.0 mL) and treated with sodium hydrogen sulfite (0.74 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and PTSA (0.15 mmol, 0.24 equiv.), respectively. The reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 16–20 h. Water (80 mL) was added to the reaction, and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration, purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 30:1) gave final compounds 15a‒e (37%–58% yield), respectively.

4.2.9.1. 2-(4-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-2-fluorophenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (15a)

Light yellow solid, Yield 47%. m.p. 233–235 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.28 (1H, brs), 7.81 (1H, dd, J = 6.7 Hz, 1.8 Hz), 7.69–7.66 (1H, m), 7.46–7.44 (1H, m), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.59 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 3.88 (3H, s), 3.86 (3H, s), 3.75–3.54 (8H, m), 1.27–1.24 (1H, m), 0.75–0.71 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 168.1, 164.7, 161.4, 159.5, 159.1, 153.2, 150.5, 132.5 (d, JC-F = 9.1 Hz), 132.0, 130.4, 122.6 (d, JC-F = 13.8 Hz), 117.1, 116.8, 105.4, 101.9, 56.5, 56.4, 56.1, 54.0, 45.3, 42.3, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C25H26FN4O5 [M+H]+: m/z 481.1887, Found 481.1886.

4.2.9.2. 2-(4-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-2-fluorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (15b)

Off-white solid, Yield 41%. m.p. 197–199 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.63 (1H, brs), 8.18 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.89–7.85 (2H, m), 7.75 (1H, s), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.58 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 7.2 Hz), 7.49 (1H, dd, J = 9.2, 8.8 Hz), 3.76–3.55 (8H, m), 1.21–1.19 (1H, m), 0.76–0.72 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 168.1, 161.9, 159.1, 149.7, 149.0, 135.1, 132.2 (d, JC-F = 9.4 Hz), 130.5, 128.0, 127.6, 126.3, 122.8 (d, JC-F = 14.3 Hz) 121.6, 117.1, 116.8, 56.1, 54.0, 46.8, 42.3, 19.3, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C23H22FN4O3 [M+H]+: m/z 421.1676, Found 421.1677.

4.2.9.3. 2-(2-Fluoro-4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl)phenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (15c)

Yellow solid, Yield 35%. m.p. 195–197 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.19 (1H, brs), 7.91 (1H, dd, J = 2.0 Hz, 6.8 Hz), 7.78–7.25 (1H, m), 7.52–7.48 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.59 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.97 (2H, s), 4.27–4.25 (2H, m), 4.05–4.00 (2H, m), 3.87 (3H, s), 3.86 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 170.0, 164.8, 161.5, 159.5, 152.9, 151.1, 150.5, 132.5 (q, JC-F = 274.8 Hz), 131.7, 130.6, 122.5 (d, J = 13.9 Hz), 120.7, 117.6, 117.1 (d, JC-F = 22.4 Hz), 105.4, 101.7, 98.7, 56.5, 52.8, 25.9, 22.8, 19.2. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C23H19F4N6O4 [M+H]+: m/z 519.1404, Found 519.1408.

4.2.9.4. 2-(2-Fluoro-4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl)phenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (15d)

Off-white solid, Yield 37%. m.p. 202–204 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.66 (1H, brs), 8.18 (1H, dd, J = 0.8 Hz, 7.8 Hz), 7.95 (1H, dd, J = 1.9 Hz, 7.0 Hz), 7.87 (1H, dd, J = 1.9 Hz, 6.8 Hz), 7.80–7.77 (1H, m), 7.73 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.59 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.52 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 4.98 (2H, s), 4.27–4.25 (2H, m), 4.05–4.00 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 168.7, 161.9, 159.4, 151.1, 149.6, 149.6, 135.1, 131.7, 130.7, 127.9 (q, JC-F = 274.8), 126.3, 122.9 (d, JC-F = 8.9 Hz), 121.6, 120.3, 117.9 (d, JC-F = 17.8 Hz), 114.9, 43.6, 22.9, 21.8. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C21H15F4N6O2 [M+H]+: m/z 459.1192, Found 459.1189.

4.2.9.5. 2-(4-(4-(Cyclopropanecarbonyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-2-fluorophenyl)-5-methoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (15e)

Light yellow solid, Yield 58%. m.p. 229–231 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.28 (1H, brs), 7.81 (1H, dd, J = 6.7 Hz, 1.8 Hz), 7.72 (1H, m), 7.70–7.66 (1H, m), 7.47 (1H, dd, J = 8.8, 8.6 Hz), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.76–3.55 (8H, m), 1.21–1.17 (1H, m), 0.75–0.71 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 171.8, 168.1, 161.6, 160.2, 159.1, 151.5, 150.0, 135.4, 132.1 (d, JC-F = 8.7 Hz), 131.9, 130.4, 122.6 (d, JC-F = 13.6 Hz) 119.8, 117.0, 116.8, 111.2, 109.3, 56.4, 56.1, 54.0, 45.2, 42.3, 10.8, 7.6 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C24H24FN4O3 [M+H]+: m/z 451.1782, Found 451.1783.

4.2.10. Preparation of compounds 18a‒u

1,2-Dibromoethane (45 mmol, 3 equiv.) was added to a mixture of para-hydroxybenzaldehyde analogue (compounds 16a‒u, 15 mmol, 1 equiv.) and potassium carbonate (24 mmol, 3 equiv.) in DMF (40 mL), and the resulting mixture was stirred vigorously at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was poured into water (150 mL), added saturated sodium chloride (150 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated sodium chloride (100 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated in vacuo to afford compounds 17a‒h (85%–96% yield), respectively. Hydroxyl-substituted compounds (10 mmol, 1 equiv.) was added to a mixture of chemical intermediate and potassium carbonate (30 mmol, 3 equiv.) in DMF (35 mL), and the resulting mixture was stirred vigorously at room temperature overnight, or heat at 80 °C for about 8 h. The mixture was poured into water (80 mL), added saturated sodium chloride (80 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated sodium chloride (100 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated in vacuo to afford chemical intermediate as solid to obtain compounds 18a‒u (76%–87% yield).

4.2.11. Preparation of target compounds19a‒u

2-Amino-4,6-dimethoxybenzamide (0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) and compound intermediates (18a‒u) (0.61 mmol, 1 equiv.) were dissolved in DMAc (8.0 mL) and treated with sodium hydrogen sulfite (0.74 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) and PTSA (0.15 mmol, 0.24 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C for 16–20 h. Water (80 mL) was added to the reaction, and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration, purification of this solid by silica gel chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol = 50:1–20:1) gave final compounds 19a‒u (17%–56% yield), respectively.

4.2.11.1. 2-(2-(4-Chloro-2-(5,7-dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)phenoxy)ethoxy)benzamide (19a)

Off-white solid, Yield 23%. m.p. 231–233 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.99 (1H, brs), 8.08 (1H, d, J = 5.6 Hz), 8.06 (1H, s), 7.86 (1H, dd, J = 7.6 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.50 (1H, dd, J = 8.3 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.42–7.41 (1H, m), 7.23 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.08–7.07 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.53 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.60–4.52 (4H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.7, 164.6, 161.3, 159.2, 156.6, 155.8, 153.4, 151.7, 132.7, 131.2, 130.2, 125.2, 124.4, 123.7, 121.4, 115.8, 113.8, 105.4, 101.8, 98.4, 68.3, 67.8, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C25H23ClN3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 496.1275, Found 496.1270.

4.2.11.2. 2-(3-(4-Chloro-2-(5,7-dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)phenoxy)propoxy)benzamide (19b)

Off-white solid, Yield 31%. m.p. 195–197 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.69 (1H, brs), 7.75–7.73 (2H, m), 7.70 (1H, d, J = 2.7 Hz), 7.55 (2H, dd, J = 8.9 Hz, 2.9 Hz), 7.39–7.34 (1H, m), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.55 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.28–4.22 (4H, m), 2.24–2.21 (2H, m), 3.86 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 167.0, 164.6, 161.4, 159.2, 156.6, 155.8, 153.5, 152.1, 132.7, 132.6, 132.0, 130.0, 124.7, 123.9, 121.0, 120.9, 115.2, 113.4, 105.4, 101.8, 98.3, 66.2, 65.9, 56.4, 56.1, 28.8. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C26H25ClN3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 510.1432, Found 510.1434.

4.2.11.3. 2-(4-(4-Chloro-2-(5,7-dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)phenoxy)butoxy)benzamide (19c)

Off-white solid, Yield 21%. m.p. 184–186 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.60 (1H, brs), 7.77–7.74 (1H, m), 7.55 (1H, dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.7 Hz), 7.39–7.35 (1H, m), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz), 7.04 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.01–6.98 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.55 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.18–4.10 (4H, m), 3.87 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s), 1.96–1.89 (4H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.9, 164.7, 161.4, 159.1, 156.9, 156.9, 153.5, 152.0, 132.8, 132.1, 131.1, 129.9, 124.6, 124.2, 123.3, 120.8, 115.4, 113.4, 105.3, 101.8, 98.3, 68.9, 68.5, 56.4, 56.1, 26.8, 26.5. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C27H27ClN3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 524.1588, Found 524.1586.

4.2.11.4. 2-(2-(4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)phenoxy)ethoxy)benzamide (19d)

Pure white solid, Yield 45%. m.p. 282–284 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.92 (1H, brs), 8.17 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz), 7.87 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.50–7.49 (1H, m), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.13 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.09–7.07 (1H, m), 6.72 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.51 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.51–4.49 (4H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 167.2, 165.5, 162.2, 162.0, 161.1, 157.6, 154.4, 133.9, 132.3, 131.2, 130.7, 126.2, 124.0, 123.3, 122.4, 115.8, 114.9, 105.8, 102.4, 98.7, 68.5, 67.6, 57.2, 56.8. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C25H24N3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 462.1665, Found 462.1664.

4.2.11.5. 2-((5-(4-Chloro-2-(5,7-dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)phenoxy)pentyl)oxy)benzamide (19e)

Off-white solid, Yield 17%. m.p. 189–191 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.56 (1H, brs), 7.76 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz), 7.55 (2H, dd, J = 8.9 Hz, 2.8 Hz), 7.47–7.41 (2H, m), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.9 Hz), 7.08 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.06–4.15 (4H, m), 3.86 (3H, s), 3.83 (3H, s), 1.87–1.78 (4H, m), 1.67–1.64 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.8, 164.7, 161.4, 159.1, 156.9, 156.1, 153.5, 152.0, 132.9, 131.1, 129.8, 129.6, 124.6, 124.2, 123.3, 120.8, 115.4, 113.4, 105.4, 101.8, 98.3, 69.2, 68.9, 56.4, 56.1, 26.8, 26.5, 22.4. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C28H29ClN3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 538.1745, Found 538.1744.

4.2.11.6. 2-(2-(4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2,6-dimethylphenoxy)ethoxy)benzamide (19f)

A white solid, Yield 51%. m.p. 271–273 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.83 (1H, brs), 7.89 (1H, d, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.69 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.50 (1H, td, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.6 Hz), 7.23 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.08 (1H, dd, J = 7.3 Hz, 7.6 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.47–4.24 (4H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s), 2.30(6H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.5, 164.7, 161.4, 160.2, 158.3, 156.8, 154.9, 153.6, 152.9, 133.1, 131.6, 131.2 (2C), 128.8, 128.1, 123.1, 121.4, 113.6, 105.1, 101.6, 98.0, 70.5, 68.5, 56.4, 56.1, 16.7 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C27H28N3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 490.1978, Found 490.1974.

4.2.11.7. 2-(2-(4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy)ethoxy)benzamide (19g)

Pale yellow solid, Yield 26%. m.p. 271–273 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.92 (1H, brs), 7.97 (1H, dd, J = 7.7 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.76 (1H, s), 7.63 (1H, s), 7.49 (1H, td, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.17 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.07–7.05 (1H, m), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.53 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.35 (4H, s), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s), 3.83 (6H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.4, 164.7, 161.4, 160.2, 157.1, 153.4, 153.4, 152.7, 138.7, 133.2, 131.8, 128.2, 122.5, 121.2, 115.2, 113.4, 105.5, 105.5, 105.1, 101.7, 98.2, 70.9, 68.3, 56.6 (2C), 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C27H28N3O8 [M+H]+: m/z 522.1876, Found 522.1873.

4.2.11.8. 2-(2-(4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2-fluorophenoxy)ethoxy)benzamide (19h)

Off-white solid, Yield 42%. m.p. 210–212 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.92 (1H, brs), 7.77 (1H, d, J = 2.7 Hz), 7.74 (1H, dd, J = 7.7 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.58 (1H, dd, J = 8.9 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.51 (1H, s), 7.36 (1H, td, J = 8.4 Hz, 1.7 Hz), 7.14 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 6.99–6.97 (1H, m), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.52–4.46 (4H, m), 3.85 (3H, s), 3.82 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 166.7, 164.6, 161.4, 159.2, 156.6, 155.8, 153.4, 151.8, 132.7, 132.1, 131.2, 130.2, 125.2 (d, JC-F = 8.2 Hz), 124.4, 123.7, 121.4, 115.8 (d, JC-F = 19.4 Hz), 113.8, 105.4, 101.8, 98.4, 68.3, 67.8, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C26H23FN3O6 [M+H]+: m/z 480.1571, Found 480.1568.

4.2.11.9. 2-(4-(2-((1H-Benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)oxy)ethoxy)-3,5-dimethylphenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (19i)

Off-white solid, Yield 38%. m.p. 186–188 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.85 (1H, brs), 8.10 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.93 (2H, s), 7.87 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.66 (1H, dd, J = 7.3 Hz, 7.9 Hz), 7.49 (1H, dd, J = 7.9 Hz, 7.6 Hz), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.92–4.90 (2H, m), 4.29–4.27 (2H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s), 2.36 (6H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.7, 161.4, 160.2, 158.4, 153.5, 152.9, 143.2, 131.2, 131.1, 129.0, 128.8 (2C), 128.1, 127.4, 125.5, 120.2, 109.7, 105.1, 101.6, 98.1, 80.6, 69.7, 56.4, 56.1, 16.7 (2C). HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C26H26N5O5 [M+H]+: m/z 488.1934, Found 488.1933.

4.2.11.10. 2-(4-(2-((1H-Benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)oxy)ethoxy)-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (19j)

Pale white solid powder, Yield 34%. m.p. 222–224 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 12.04 (1H, brs), 8.08 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.91 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.66 (1H, dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 7.9 Hz), 7.58 (2H, s), 7.48 (1H, dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 7.9 Hz), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.53 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.84 (2H, t, J = 3.4 Hz), 4.35(2H, t, J = 3.4 Hz), 3.90 (9H, s), 3.86 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.7, 161.4, 160.9, 160.3, 153.4, 153.1, 152.6, 143.2, 139.2, 128.8 (2C), 127.7, 125.4 (2C), 120.1, 109.6, 105.5 (2C), 105.2, 101.7, 98.2, 80.8, 70.2, 56.6, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C26H26N5O7 [M+H]+: m/z 520.1832, Found 520.1828.

4.2.11.11. 2-(4-(2-((1H-Benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)oxy)ethoxy)phenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (19k)

Off-white solid, Yield 48%. m.p. 233–235 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.92 (1H, brs), 8.17 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 8.09 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.29 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.60 (1H, dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 7.8 Hz), 7.46 (1H, dd, J = 7.9 Hz, 7.4 Hz), 7.03 (2H, d, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.51 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.96–4.46 (4H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.7, 161.4, 160.9, 160.0, 153.6, 152.8, 143.2, 129.8 (2C), 128.9, 127.1, 125.4, 125.3, 120.2, 114.8 (2C), 109.6, 105.0, 101.6, 97.9, 79.3, 65.8, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C24H22N5O5 [M+H]+: m/z 460.1621, Found 460.1607.

4.2.11.12. 2-(4-(2-((1H-Benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)oxy)ethoxy)-3-fluorophenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (19l)

Off-white solid, Yield 32%. m.p. 233–236 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 11.99 (1H, brs), 8.09–8.04 (3H, m), 7.81 (1H, d, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.60 (1H, dd, J = 7.2 Hz, 8.0 Hz), 7.46 (1H, dd, J = 8.0 Hz, 7.4 Hz), 7.36–7.34 (1H, m), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 6.53 (1H, d, J = 2.2 Hz), 4.99–4.98 (2H, m), 4.56–4.54 (2H, m), 3.89 (3H, s), 3.85 (3H, s). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ (ppm): 164.7, 161.4, 160.1, 153.3, 152.8, 151.7, 148.9 (d, JC-F = 10.8 Hz), 143.2, 129.0, 128.9, 127.6, 125.9, 125.0, 120.2, 116.7 (d, JC-F = 18.9 Hz), 114.9, 109.4, 105.1, 101.7, 98.1, 79.1, 66.8, 56.4, 56.1. HR-MS (ESI) Calcd. for C24H21FN5O5 [M+H]+: m/z 478.1526, Found 478.1529.

4.2.11.13. 2-(4-(2-((1H-Indazol-6-yl)oxy)ethoxy)-3,5-dimethylphenyl)-5,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4(3H)-one (19m)