Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

The study was conducted to investigate the efficacy of the combination treatment of phytochemical resveratrol and the anticancer drug docetaxel (DTX) on prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells, including factors related to detailed cell death mechanisms.

MATERIALS/METHODS

Using 2-dimensional monolayer and 3-dimensional spheroid culture systems, we examined the effects of resveratrol and DTX on cell viability, reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, mitochondrial membrane potential, apoptosis, and necroptosis by MTT, flow cytometry, and Western blotting.

RESULTS

At concentrations not toxic to normal human prostate epithelial cells, resveratrol effectively decreased the viability of LNCaP cells depending on concentration and time. The combination treatment of resveratrol and DTX exhibited synergistic inhibitory effects on cell growth, demonstrated by an increase in the sub-G0/G1 peak, Annexin V-phycoerythrin positive cell fraction, ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage response as well as concurrent activation of apoptosis and necroptosis. Apoptosis and necroptosis were rescued by pretreatment with ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine.

CONCLUSIONS

We report resveratrol as an adjuvant drug candidate for improving the outcome of treatment in DTX therapy. Although the underlying mechanisms of necroptosis should be investigated comprehensively, targeting apoptosis and necroptosis simultaneously in the treatment of cancer can be a useful strategy for the development of promising drug candidates.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, resveratrol, docetaxel, apoptosis, necroptosis, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Many natural bioactive substances derived from plants or microorganisms have shown promising potential for the prevention and treatment of various types of cancer. In particular, their use is advantageous in that they are safe to use and can reduce the high costs associated with the development of therapeutic drugs. Among them, phenylpropanoids are secondary metabolites produced by plants in response to various types of stress, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), pathogens or herbivore attack [1]. Stilbenes belongs to the family of phenylpropanoids containing a 1,2-diphenylethylene backbone. Resveratrol (trans-3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene, resveratrol [RSV]), a stilbene, consists of 2 phenolic rings linked by an ethylene bridge [2]. RSV shows various chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic properties resulting from anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic and anti-proliferative activities [2,3]. For instance, it inhibits cancer cell growth and regulates apoptosis by regulating the action of various pro- and anti-apoptotic factors that affect apoptosis, reduce inflammatory reactions, and neutralize ROS [3,4]. In this process, several signaling pathways involved in cell survival and death are targets of its mechanisms of action. In addition to chemopreventive effects, many researchers have noted the role of RSV in enhancing the efficacy of traditional chemotherapy. In particular, RSV showed synergistic effects with anticancer agents in cells of several types of cancer including of the lung, cervical and prostate cancers [5,6,7]. Another study on RSV revealed that when combined with docetaxel (DTX), the synergistic effect of RSV on prostate cancer cells is induced by G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the p53/p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 signaling [8].

Induction of apoptosis is one of the main criteria in evaluating the efficacy of candidates for the development of anticancer drugs. Evasion of apoptosis is known to be a prominent feature of tumorigenesis and progression in human cancer [9], and resistance to conventional therapies is inevitably encountered during chemotherapy. Thus, a compound that can activate alternative cell death pathways to apoptosis would be extremely valuable. Among forms of non-apoptotic cell death, necrosis has been considered to be an accidental, unregulated type of cell death that is triggered by various factors external to the cells or tissues, such as infection, toxins, insufficient blood perfusion, and ROS [10]. In some situations, necrosis can be executed and regulated in a manner similar to programmed cell death. Receptor-interacting protein kinase-3 (RIP3) and its substrate, the mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) were activated by phosphorylation to form a necrosome that subsequently triggered cell death [11,12]. This regulated form of necrosis is referred to as necroptosis and is specifically inhibited by necrostatin-1, a specific inhibitor of RIP1 activity [12]. Given the various forms of death that can occur in cancer cells under stressful conditions, it is important to identify the underlying cell death mechanisms and related regulators in developing new anticancer strategies.

DTX is the first-line treatment for metastatic and hormone-refractory prostate cancer; it is a taxane derivative of Taxus baccata, also known as the European yew tree, and it displays potent antitumor activity [13]. DTX inhibits microtubule depolymerization by binding to and stabilizing tubulin, resulting in growth arrest and apoptosis [14]. Combination therapy is believed to enhance cancer-killing actions through simultaneous targeting of multiple oncogenic factors, or more effective inhibition of multiple pathways, incuding antioxidant response, cell survival, hypoxia, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and epigenetic modulation pathways [15]. Various combinatorial trials have also been conducted to improve the efficacy of DTX in prostate cancer, and these include doxorubicin, prednisone, estramustine, and anthracycline [16,17,18,19], and research on the efficacy of neoadjuvants is ongoing.

Androgen deprivation therapy is one of the main treatment options for patients with early-stage androgen-dependent prostate cancer, but almost all patients proceed to develop androgen-independent prostate cancer in a few years. Progress to an incurable and irreversible androgen-independent stage remains a major obstacle to effective treatment, and a strong need for alternative treatment strategies is being emphasized. The LNCaP cells used in this study are androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells, and have been used most frequently in in vitro models for basic and preclinical studies of prostate cancer.

Using prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells, we present here a novel mechanism of cell death that is induced by the combination treatment of DTX and RSV targeting apoptosis as well as necroptosis, which commonly triggers ROS-induced DNA damage. Our data also provided the basis for a potential therapeutic strategy that uses RSV as an adjuvant in treating prostate carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cell culture

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), RSV, DTX, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT reagent), lactic acid, fluorescein diacetate (FDA), propidium iodide (PI), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), necrostatin-1, Q-VD-Oph-1, casein blocking buffer, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA), rhodamine 123, and Tween-20 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Antibodies to MLKL (catalog No. 14993), p-MLKL (Catalog No. 91689), RIP3 (catalog No. 13526), p-RIP3 (catalog No. 93654), p-ATMSer1981 (catalog No. 5883), p-ATRSer428 (catalog No. 2853), p-Histone H2A.XSer139 (catalog No. 9718), Bax (catalog No. 5023), Bcl-2 (catalog No. 2820), poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP; catalog No. 9542), cleaved PARP (catalog No. 9541), and cleaved caspase-3 (catalog No. 9664) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, CO, USA). Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase (IgG-HRP; catalog No. sc-2004), mouse anti-goat IgG-HRP (catalog No. sc-2354), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (catalog No. sc-2005) were purchased from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). LNCaP (human prostate cancer) and human prostate epithelial cell (HPrEC) lines were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, USA). HPrECs grew in prostate epithelial cell basal medium supplemented with prostate epithelial cell growth kit (ATCC). LNCaP cells grew in DMEM (Welgene Inc., Gyeongsan, Korea) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/mL in 100 μL complete medium overnight, after which, cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO), RSV, and DTX for the times indicated in the figure legends. MTT reagent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Absorbance values were read at 540 nm using a GloMax-Multi microplate multimode reader (Promega Corporation, Durham, NC, USA). The percentage viability of cells was determined by comparison with the results obtained using vehicle-treated cells (100%). The combination effect of the 2 drugs was evaluated using the combination index (CI) as described previously [20]. CI values < 1, equal to 1, and > 1 were defined as synergistic, additive, and antagonistic effects, respectively.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle was analyzed by quantification of DNA content in cells stained with PI. Briefly, cells were harvested, fixed with 70% ethanol, and left at −20°C overnight. After washing and resuspension in 1× PBS, the MuseTM cell cycle reagent (Merck Millipore, Burington, MA, USA) was added to the cells. The DNA distribution from 10,000 cells was analyzed by a MACSQuant analyzer and MACSQuantifyTM software version 2.5 (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch, Germany).

Annexin V-phycoerythrin (V-PE) binding assay

Apoptotic and necrotic cell distributions were determined using the MuseTM Annexin V & Dead Cell Assay kit (Merck KGaA). Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation and labeled with Annexin V-PE and 7-amino-actinomycin D for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells (5 × 103) were then analyzed by MuseTM cell analyzer (Merck KGaA).

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed and lysed with 1× RIPA buffer and protein quantitation was performed using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell lysates containing 40 μg of protein were loaded on 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Thermo Fisher) for electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (GE Healthcare Life Science, Munich, Germany). After blocking with 1× casein blocking buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h, the membrane was incubated with various primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing with 1× PBS with Tween-20, the membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies coupled to HRP for protein detection. Reactive proteins were visualized on an X-ray film using enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Cyanagen Srl, Bologna, Italy). The membrane was re-probed with antibodies to anti-ß-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) and served as a loading control.

Measurement of ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 105 cells/mL in 2 mL complete medium/well overnight, after which cells were treated with the vehicle, RSV, DTX or RSV/DTX in complete DMEM for the indicate times in figure legends. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and then stained with 10 µM DCF-DA and 30 nM rhodamine 123 to measure the levels of ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), respectively, in the dark at 37˚C for 30 min. After washing cells with 1× PBS, the average fluorescence intensity of 10,000 cells was measured using the MACSQuant analyzer and MACSQuantifyTM software version 2.5 (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH).

Spheroid culture and viability assay

Cells (104 cells/well) were seeded in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates. The plates were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min to facilitate clustering of the cells into the wells, as described by Chambers et al. [21], and maintained in the complete DMEM. Spheroids were treated with curcumin for 48 h. Phase-contrast images were taken using a Leica inverted microscope. Spheroid viability was determined using an enhanced cell viability assay kit (CellVia, Seoul, Korea). Briefly, 10 µL of Cellvia solution was added to each well, kept at room temperature for 1 h and then mixed by shaking for 1 min. Formazan formed in living cells was measured at 450 nm using a GloMax-Multi microplate multimode reader (Promega Corporation).

Spheroid staining

Cells were incubated with FDA (5 µg/mL) and PI (10 µg/mL) in the dark to stain viable and dead cells respectively. The FDA, a cell-permeable esterase substrate, indicates viable cells by assessing enzymatic activity and cell-membrane integrity, while PI passes through damaged areas of dead or dying cell membranes into the nucleus and binds to DNA. Cells were imaged using a Leica EL6000 fluorescence microscope and LAS version 4.3 software (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

We conducted statistical comparisons using analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc correction in SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were shown as mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments. P < 0.05 means statistical significance.

RESULTS

The combination of resveratrol and DTX causes synergistic cytotoxicity

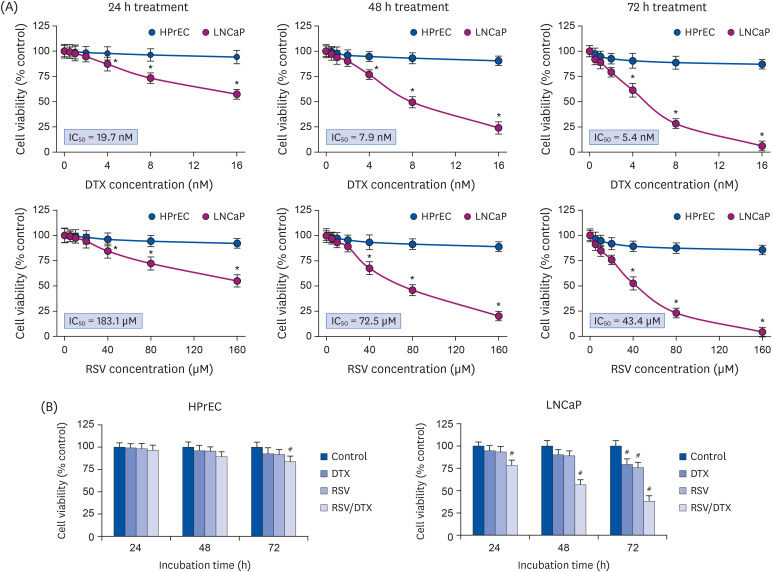

We first investigated the effects of RSV and anticancer drug DTX, alone or in combination, on the survival of prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells. Fig. 1A shows that RSV or DTX alone effectively decreased the viability of LNCaP cells depending on concentration and time; IC50 values at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h of RSV exposure were 183.1 μM, 72.5 μM, and 43.4 μM, respectively; and 19.7 nM, 7.9 nM, and 5.4 nM for DTX exposure, respectively. However, we observed little toxicity in normal HPrECs in response to RSV and DTX at the tested concentrations, indicating the selectivity of RSV and DTX to cancer cells. We then investigated the cytotoxic effects of 20 μM RSV in combination with 2 nM DTX (RSV/DTX) on both cell types after 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure. Fig. 1B indicates that RSV augmented the cytotoxic effect of DTX on LNCaP cells at all time points tested, as compared to RSV or DTX alone. Next, we evaluated the CI to determine whether the combined effect of RSV and DTX was synergistic. The CI values at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h of RSV/DTX were 0.73, 0.68, and 0.72, respectively, indicating that RSV cooperated synergistically with DTX to inhibit cell viability of LNCaP cells.

Fig. 1. Synergistic growth-inhibiting effects of RSV and DTX in LNCaP and HPrECs. (A) Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of RSV (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μM) and DTX (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 nM) for the indicated times. (B) Cells were treated with RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) alone or in combination for 24, 48, and 72 h. The percentage of viable cells was then determined by MTT assay. Error bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments.

RSV, resveratrol; DTX, docetaxel; RSV/DTX, the combination of resveratrol and docetaxel; HPrEC, human prostate epithelial cell.

*P < 0.05 compared with respective HPrEC cells; #P < 0.05 compared with respective untreated cells.

Resveratrol alone or in combination with DTX induces cell cycle transition delay at G2/M phase and DNA damage response (DDR)

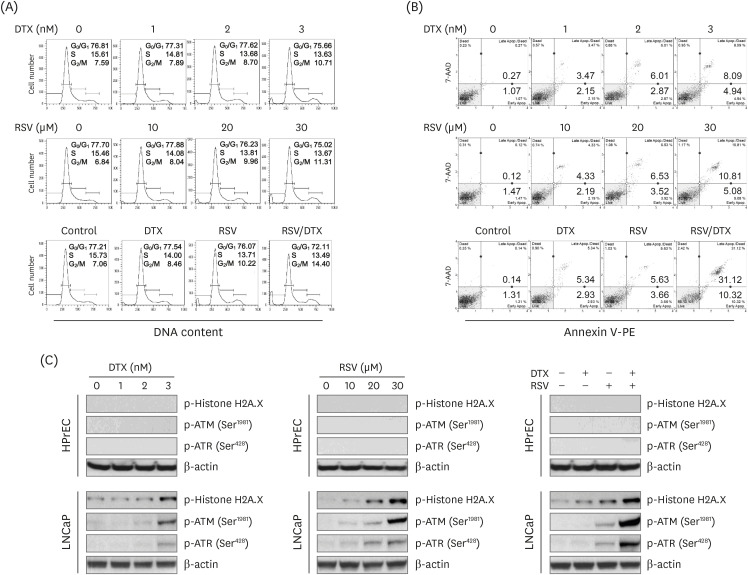

We conducted cell cycle analysis to elucidate how RSV/DTX decreased cell viability. The results of cell cycle analysis (Fig. 2A) showed that RSV/DTX caused G2/M-phase accumulation with an increase in subG0/G1 content, indicating apoptotic cell death. In Annexin V-PE staining assay, RSV/DTX remarkably increased the percentage of apoptotic cell populations (Annexin V-PE positive), as compared to RSV or DTX alone (Fig. 2B). Next, to investigate the ability of RSV/DTX to activate the DNA damage sensor kinases such as ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and RAD3-related (ATR), LNCaP cells were treated with RSV and DTX alone or in combination, after which the phosphorylated forms of ATMSer1981, ATRSer428, and histone H2A variant H2A.XSer139 as a marker of DNA double-strand breaks were measured by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2C, RSV/DTX potently increased phosphorylation of ATMSer1981, ATRSer428, and H2A.XSer139, suggesting that RSV/DTX triggers activation of the ATM/ATR signaling pathway with DNA double-strand breaks.

Fig. 2. Cytotoxic effects induced by RSV and DTX in LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of RSV and DTX, otherwise RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) alone or in combination for 48 h. (A) Cell cycle distribution was determined by flow cytometry following PI (20 μg/mL) staining. (B) Apoptotic cell fraction was analyzed using Annexin V-PE binding assay. (C) The levels of DNA damage response proteins were assessed by Western blotting.

RSV, resveratrol; DTX, docetaxel; PI, propidium iodide; ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia mutated and RAD3-related.

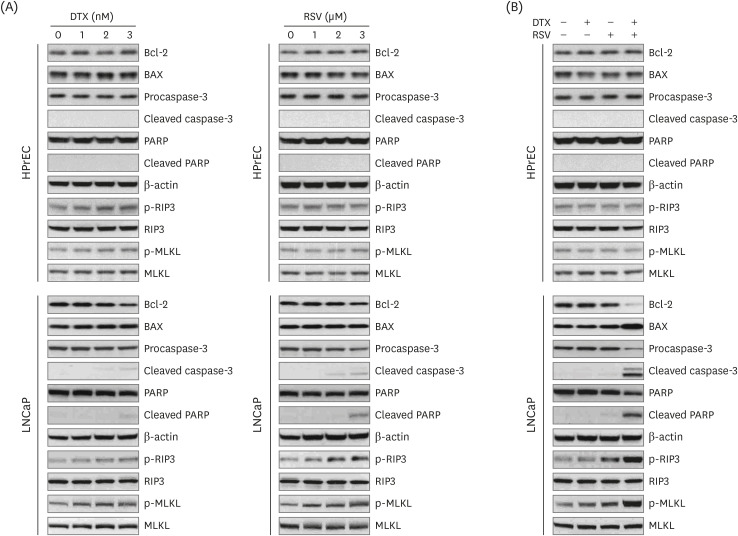

Synergistic cytotoxicity of resveratrol and DTX concurrently induces apoptosis and necroptosis

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying synergistic cytotoxicity of RSV/DTX, we measured levels of proteins involved in apoptosis and necroptosis by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3, RSV/DTX further increased the cleaved forms of caspase-3 and its substrate PARP as well as Bcl-2-associated X protein/B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bax/Bcl-2) ratio, compared with those induced by RSV and DTX alone. Furthermore, RSV/DTX increased the levels of p-MLKL and p-RIP3 as necroptosis mediators. Inhibition of either necroptosis or of apoptosis by pretreatment with necrostatin-1 or Q-VD-Oph-1, respectively, enhanced cell viability (Fig. 4A) and reversed the levels of apoptosis- or necroptosis-inducing molecules in LNCaP cells treated with RSV/DTX (Fig. 4B). This strongly suggests that RSV/DTX-induced cell death is mediated by concurrent induction of both apoptosis and necroptosis. Previous evidence has demonstrated that cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels controlled both cell death processes [22]. To determine the role of ATP in the synergistic cytotoxicity of RSV/DTX, we examined the effects of ATP supplementation in RSV/DTX-treated LNCaP cells. Adding ATP improved cell viability (Fig. 4A) and decreased the levels of apoptosis- or necroptosis-inducing molecules (Fig. 4B). Next, we measured changes in ΔΨm by RSV/DTX to evaluate mitochondrial function. The combination treatment caused a marked loss of ΔΨm in 42.46% of the cell population compared to RSV (10.72%) or DTX (8.87%) alone (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these findings indicated that RSV/DTX-induced cell death was caused, at least in part, by ATP depletion.

Fig. 3. Expression of apoptosis- and necroptosis-related proteins by RSV and DTX in LNCaP and HPrECs. (A) Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of RSV (0, 10, 20, and 30 μM) and DTX (0, 1, 2, and 3 nM) for 48 h. (B) Cells were treated with RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) alone or in combination for 48 h. The levels of apoptosis- and necroptosis-related proteins were assessed by Western blotting.

RSV, resveratrol; DTX, docetaxel; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BAX, Bcl-2-associated X protein; PARP, poly ADP-ribose polymerase; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein kinase-3; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; HPrEC, human prostate epithelial cell.

Fig. 4. Apoptosis, necroptosis, and oxidative mitochondrial dysfunction in LNCaP cell treated with RSV and DTX. Cells were pretreated with necrostatin-1 (25 μM), Q-VD-Oph-1(10 μM), and ATP (1 mM) 2 h prior to treatment with RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) in combination. (A) The percentage of viable cells was then determined by MTT assay. (B) The levels of apoptosis- and necroptosis-related proteins were assessed by Western blotting. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of RSV and DTX, otherwise RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) alone or in combination for 48 h. (C) ΔΨm was measured after cells were stained with 30 nM rhodamine 123.

RSV, resveratrol; DTX, docetaxel; RSV/DTX, the combination of resveratrol and docetaxel; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein kinase-3; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; ATP, adenosine triphosphate.

*P < 0.05 vs. respective untreated cells.

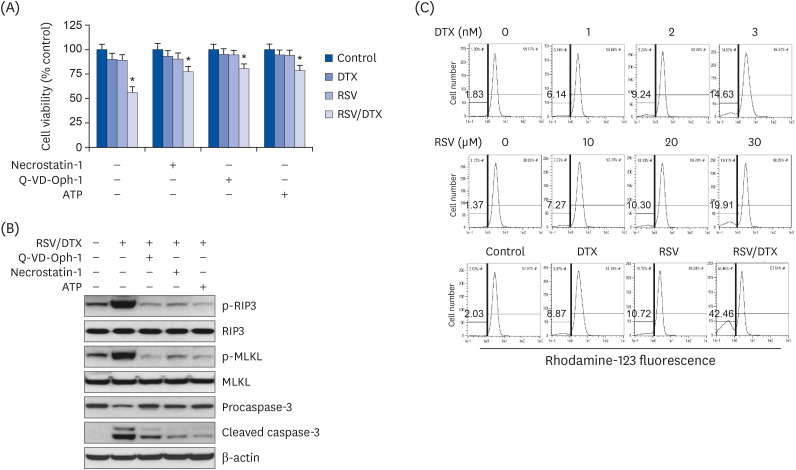

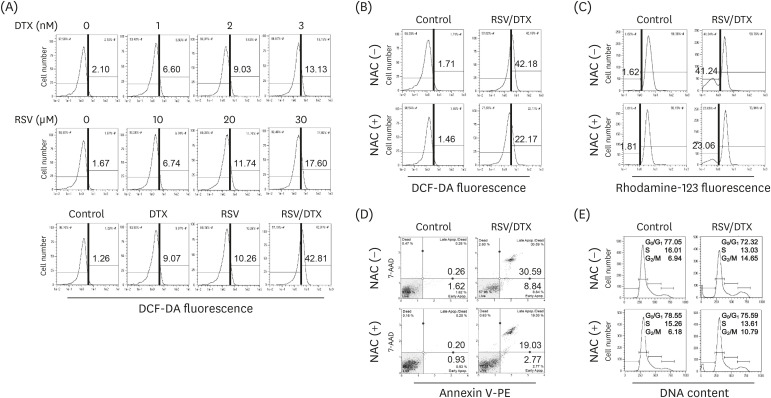

Excessive ROS is an upstream molecule that causes synergistic cytotoxicity of resveratrol and DTX

To investigate whether intracellular ROS was involved in the cytotoxicity induced by RSV/DTX in LNCaP cells, we performed DCF fluorescence assay using flow cytometry. With the increasing RSV or DTX concentration, cellular ROS levels tended to gradually increase but showed a marked increase at 48 h of combination treatment (Fig. 5A). In addition, pretreatment of LNCaP cells with ROS scavenger NAC effectively improved a series of effects induced by RSV/DTX, including cellular ROS levels (Fig. 5B), percentage of cells showing ΔΨm loss (Fig. 5C), Annexin V-PE positivity (Fig. 5D), and transition delay in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. Effects of ROS scavenger NAC on cytotoxicity induced by RSV and DTX in LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of RSV and DTX, otherwise RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) alone or in combination for 48 h. (A) Cellular ROS levels were measured after cells were stained with 10 μM DCF-DA. Cells were pretreated with 5 mM NAC for 2 h prior to treatment with RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) in combination. (B) Cellular ROS levels were measured by staining cells with 10 μM DCF-DA. (C) ΔΨm was measured by staining cells with 30 nM rhodamine123. (D) Apoptotic cell fraction was analyzed using Annexin V-PE binding assay. (E) Cell cycle distribution was determined by flow cytometry following PI (20 μg/mL) staining.

ROS, reactive oxygen species; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; RSV, resveratrol; DTX, docetaxel; RSV/DTX, the combination of resveratrol and docetaxel; DCF-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate.

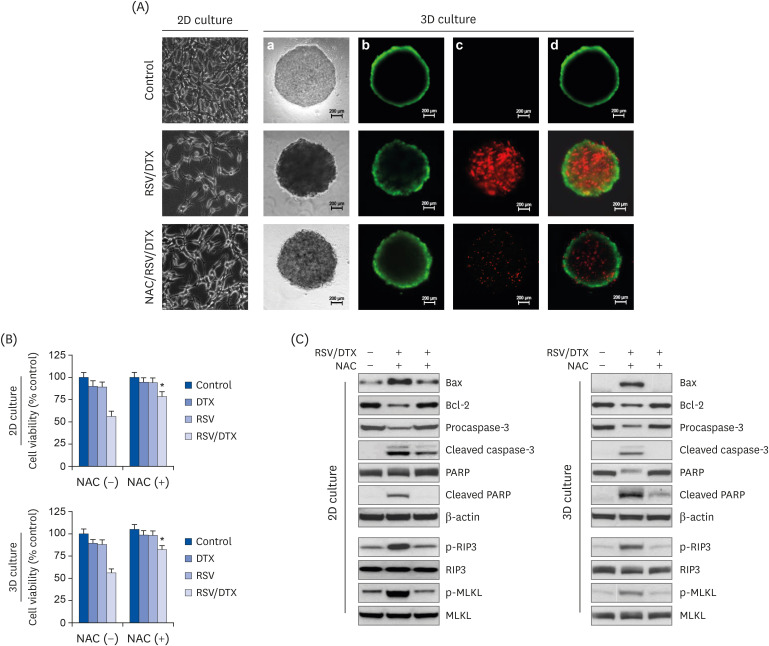

To determine whether the results of 2-dimensional (2D) monolayer culture matched in 3-dimensional (3D) culture, spheroids derived from LNCaP cells were pretreated with NAC for 2 h before being processed for another 48 h with RSV/DTX. Viable and dead cells were visualized under fluorescence microscope after double staining with FDA (green) and PI (red), respectively. RSV/DTX increased red fluorescence in the necrotic core with green fluorescence on the spheroid surface, which correlated with decreased spheroid viability; however, this phenomenon was blocked by NAC pretreatment. Next, we investigated whether the expression of proteins related to apoptosis- and necroptosis are affected by RSV/DTX. As shown in Fig. 6C, RSV/DTX increased p-RIP3, p-MLKL, Bax, and cleaved form of caspase-3 and PARP proteins, and decreased Bcl-2, but NAC pretreatment significantly recovered changes in these proteins. Changes in cell viability and cell death-related protein levels observed in the 3D spheroid culture for RSV/DTX showed similar trends as those found in 2D monolayer culture.

Fig. 6. Cell viability, morphology, and Western blotting analysis by RSV and DTX in 2D monolayer and 3D spheroid culture of LNCaP cells. Cells and spheroids were pretreated with or without 5 mM NAC 2 h prior to treatment with RSV (20 μM) and DTX (2 nM) in combination. (A) Vitality staining of cells (phase-contrast image of 2D monolayer cells) and spheroids [from left to right: phase-contrast image (a), fluorescent images of FDA(+) living cells in green (b), PI(+) dead cells in red (c), and merged (d)]. (B) Cells and spheroid viability were measured by MTT assay and the enhanced cell viability assay, respectively. (C) The levels of necroptosis- and apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed by Western blotting.

RSV, resveratrol; 2D, 2-dimensional; 3D, 3-dimensional; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; DTX, docetaxel; RSV/DTX, the combination of resveratrol and docetaxel; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BAX, Bcl-2-associated X protein; PARP, poly ADP-ribose polymerase; RIP3, receptor-interacting protein kinase-3; MLKL, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; FDA, fluorescein diacetate; PI, propidium iodide.

*P < 0.05 vs. respective NAC-untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

Our studies showed that RSV synergistically augmented the anticancer effects of DTX by increasing both apoptosis and necroptosis in 2D monolayer and 3D spheroid culture models of prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells. Sensitizing effects of RSV to DTX were elicited at least in part through ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and DNA damage, suggesting RSV as an adjuvant candidate for DTX therapy in prostate carcinoma.

In this study, a synergistic cytotoxic effect by RSV/DTX treatment targeted 2 cell death pathways. First, RSV/DTX suppressed Bcl-2 and increased Bax to stimulate apoptosis. The mechanism by which cancer cells can escape apoptosis is multi-factorial and involves a number of mediators, and among these, Bcl-2 overexpression is well understood for its role in suppressing the activation of apoptotic cascades during prostate cancer treatment [23]. Consistently, Bcl-2 inhibitors have been shown to reverse chemoresistance and to enhance sensitivity to other chemotherapeutic agents in prostate cancer [23,24]. Second, RSV/DTX potently induced cell death through necroptosis, as evidenced by activation of RIP3 and MLKL, an increase in the Annexin V-PE(+)/PI(+) cell fraction, and enhancement in the cell viability following pretreatment with necroptosis inhibitor. Activating necroptosis depends on sequential activation of RIP3 and MLKL by phosphorylation to form a necrosome. Unlike uncontrolled cell necrosis, necroptosis can be mitigated or reversed by necrostatin-1 [12], and inducing non-apoptotic cell death may provide therapeutic advantages in cancer cells, especially in cells with apoptotic defects.

Mitochondria are closely related to the induction of intrinsic apoptotic pathways that are usually triggered by metabolic, replicative or genotoxic stresses. Unlike in apoptosis, the role of mitochondria in necroptosis is still unclear and requires further evaluation. However, in several reports on the association mitochondrial damage with necroptosis, the presence of necroptosis-related proteins in mitochondria and the interaction with Drp1 during necroptosis demonstrated mitochondrial involvement [25,26,27].

DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic drugs exert their cytotoxic effects by inducing different types of DNA damage, including DNA base conversion, crosslinking between bases, and single- or double-strand breaks in the DNA backbone [28]. To preserve genome integrity and maintain cell homeostasis, cells respond to various forms of DNA damage by promoting the DDR, which recruits ATM and ATR kinases to subsequently activate DNA repair signaling. The DDR in damaged cells can lead to growth arrest, DNA repair, cell aging or apoptosis [29,30]. A similar induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, observed in the present study, has been reported before for 2 androgen-independent prostate cancer cells (DU145 and C4-2B cells) exposed to the combined treatment of DTX and RSV [8]. This effect has been associated with up-regulation of tumor suppressor p53 and cell cycle inhibitors, p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1. In this study, our finding demonstrated a transition delay at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle with the activation of DDR following RSV/DTX treatment, suggesting that cell protective mechanisms for correcting potentially harmful mutated cells and removing them before the next cell cycle are at work; however, activation of apoptosis and necroptosis implied an increase in irreversibly damaged cells [31]. Inhibiting necroptosis and apoptosis using inhibitors such as necrostatin-1 and Q-VD-Oph-1 could rescue the viability of cells treated with RSV/DTX and reverse increase in apoptosis- or necroptosis-inducing molecules. The presence of necrostatin-1 reduced p-RIP3 and p-MLKL as well as cleaved caspase-3, with similar results seen in the presence of Q-VD-Oph-1. This indicated that RSV/DTX-induced necroptosis and apoptosis can occur interdependently, at least to a some degree; therefore, further evaluation is needed to demonstrate possible crosstalk between the 2 processes.

In the present study, RSV/DTX caused high level of ROS generation in LNCaP cells. ROS scavenger NAC prevented ROS production and inhibited RSV/DTX-induced apoptosis and necroptosis, suggesting that ROS are upstream molecules of RSV/DTX-promoted cell death. ROS are not only involved in the apoptotic response, but can also activate necroptosis [32]. Cellular ROS are highly generated in mitochondria [32] and excess ROS cause oxidative stress and DNA damage, leading to ΔΨm loss, energy depletion, and ultimately activation of specific pathways to determine cell fate [33,34]. In general, ROS levels are much higher in cancer cells than in normal cells [35]; therefore, oxidative stress caused by ROS overproduction can effectively kill cancer cells by increasing them to levels beyond the threshold for cell death. In this regard, pro-oxidant-based induction of both apoptosis and necroptosis by RSV/DTX is another advantage for selectively killing cancer cells and overcoming apoptotic resistance in prostate carcinoma.

In vitro 2D monolayer cultures of tumor cells have difficulty in replicating the natural structure of tumors in vivo, cell-cell or cell-extracellular matrix interactions that occur in the tumor mass, and metabolic stresses found in tumor microenvironment, such as hypoxia, acidic pH and diminished nutrients access. Therefore, 2D culture results tend to overestimate the therapeutic potential of drug candidates and sometimes do not match the results of in vivo assays [36]. To compensate for these drawbacks, 3D spheroid culture is considered as a suitable model for screening drug candidates. In 3D cultures treated with RSV/DTX, increased fluorescent image of PI(+) areas inside the spheroid showing necrotic cell death and decreased cell viability were improved by NAC pretreatment. Furthermore, effective reversal by NAC at the level of proteins related to apoptosis and necroptosis in 3D spheroids confirms the results of 2D cell cultures. There are numerous reports that the results of 3D spheroid culture do not always reflect the results of 2D monolayer culture, but our findings show that the mechanism of cell death by RSV/DTX treatment of LNCaP cells is consistent in both 2D and 3D models.

In conclusion, our data show that RSV/DTX induces synergistic cytotoxicity of prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells through targeting apoptosis and necroptosis simultaneously. ROS-induced DNA damage is an upstream event that may be common to both of these cell death modalities. Our findings provided a basis for considering the potential therapeutic value of RSV as an adjuvant to treat prostate carcinoma, and in addition may be worth developing as a therapeutic agent for apoptosis-resistant carcinoma.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education (No. NRF-2017R1D1A3B04031891).

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests.

- Conceptualization: Lee YJ, Lee SH.

- Data curation: Lee YJ, Lee SH.

- Formal analysis: Lee YJ, Lee SH.

- Investigation: Lee YJ.

- Project administration: Lee YJ.

- Writing - original draft: Lee SH.

- Writing - review & editing: Lee YJ, Lee SH.

References

- 1.War AR, Paulraj MG, Ahmad T, Buhroo AA, Hussain B, Ignacimuthu S, Sharma HC. Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal Behav. 2012;7:1306–1320. doi: 10.4161/psb.21663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salehi B, Mishra AP, Nigam M, Sener B, Kilic M, Sharifi-Rad M, Fokou PV, Martins N, Sharifi-Rad J. Resveratrol: a double-edged sword in health benefits. Biomedicines. 2018;6:91. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko JH, Sethi G, Um JY, Shanmugam MK, Arfuso F, Kumar AP, Bishayee A, Ahn KS. The role of resveratrol in cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2589. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takashina M, Inoue S, Tomihara K, Tomita K, Hattori K, Zhao QL, Suzuki T, Noguchi M, Ohashi W, Hattori Y. Different effect of resveratrol to induction of apoptosis depending on the type of human cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2017;50:787–797. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu S, Li X, Xu R, Ye L, Kong H, Zeng X, Wang H, Xie W. The synergistic effect of resveratrol in combination with cisplatin on apoptosis via modulating autophagy in A549 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2016;48:528–535. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmw026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang TW, Lin CY, Tzeng YJ, Lur HS. Synergistic combinations of tanshinone IIA and trans-resveratrol toward cisplatin-comparable cytotoxicity in HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:5473–5480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kai L, Levenson AS. Combination of resveratrol and antiandrogen flutamide has synergistic effect on androgen receptor inhibition in prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3323–3330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh SK, Banerjee S, Acosta EP, Lillard JW, Singh R. Resveratrol induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis with docetaxel in prostate cancer cells via a p53/p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17216–17228. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma A, Boise LH, Shanmugam M. Cancer metabolism and the evasion of apoptotic cell death. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1144. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zong WX, Thompson CB. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.1376506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su Z, Yang Z, Xie L, DeWitt JP, Chen Y. Cancer therapy in the necroptosis era. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:748–756. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong Y, Fan Z, Luo G, Yang C, Huang Q, Fan K, Cheng H, Jin K, Ni Q, Yu X, Liu C. The role of necroptosis in cancer biology and therapy. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi I, Watanabe T, Takashima S, Narabayashi M, Horikoshi N, Aoyama H, Taguchi T. A late phase II study of RP56976 (docetaxel) in patients with advanced or recurrent breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:210–216. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-Vargas H, Palacios J, Moreno-Bueno G. Telling cells how to die: docetaxel therapy in cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:780–783. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.7.4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayat Mokhtari R, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B, Yeger H. Combination therapy in combating cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:38022–38043. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsakalozou E, Eckman AM, Bae Y. Combination effects of docetaxel and doxorubicin in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:832059. doi: 10.1155/2012/832059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrylak DP. Docetaxel for the treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2003;5 Suppl 2:S14–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savarese DM, Halabi S, Hars V, Akerley WL, Taplin ME, Godley PA, Hussain A, Small EJ, Vogelzang NJ. Phase II study of docetaxel, estramustine, and low-dose hydrocortisone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a final report of CALGB 9780. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2509–2516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budman DR, Calabro A, Kreis W. Synergistic and antagonistic combinations of drugs in human prostate cancer cell lines in vitro . Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:1011–1016. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YJ, Lee YJ, Im JH, Won SY, Kim YB, Cho MK, Nam HS, Choi YJ, Lee SH. Synergistic anti-cancer effects of resveratrol and chemotherapeutic agent clofarabine against human malignant mesothelioma MSTO-211H cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;52:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers KF, Mosaad EM, Russell PJ, Clements JA, Doran MR., 3rd 3D cultures of prostate cancer cells cultured in a novel high-throughput culture platform are more resistant to chemotherapeutics compared to cells cultured in monolayer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1835–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bray K, Chen HY, Karp CM, May M, Ganesan S, Karantza-Wadsworth V, DiPaola RS, White E. Bcl-2 modulation to activate apoptosis in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1487–1496. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang XQ, Huang XF, Hu XB, Zhan YH, An QX, Yang SM, Xia AJ, Yi J, Chen R, Mu SJ, Wu DC. Apogossypolone, a novel inhibitor of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, induces autophagy of PC-3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cells in vitro . Asian J Androl. 2010;12:697–708. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Jiang W, Yan Y, Gong T, Han J, Tian Z, Zhou R. RNA viruses promote activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through a RIP1-RIP3-DRP1 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1126–1133. doi: 10.1038/ni.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF, Wang FS, Wang X. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell. 2014;54:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Zhou Z, Li L, Zhong CQ, Zheng X, Wu X, Zhang Y, Ma H, Huang D, Li W, Xia Z, Han J. Diverse sequence determinants control human and mouse receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) interaction in necroptotic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:16247–16261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheung-Ong K, Giaever G, Nislow C. DNA-damaging agents in cancer chemotherapy: serendipity and chemical biology. Chem Biol. 2013;20:648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt E, Paquet C, Beauchemin M, Bertrand R. DNA-damage response network at the crossroads of cell-cycle checkpoints, cellular senescence and apoptosis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8:377–397. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearl LH, Schierz AC, Ward SE, Al-Lazikani B, Pearl FM. Therapeutic opportunities within the DNA damage response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:166–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borges HL, Linden R, Wang JY. DNA damage-induced cell death: lessons from the central nervous system. Cell Res. 2008;18:17–26. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulze-Osthoff K, Bakker AC, Vanhaesebroeck B, Beyaert R, Jacob WA, Fiers W. Cytotoxic activity of tumor necrosis factor is mediated by early damage of mitochondrial functions. Evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial radical generation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5317–5323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:2977–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmström KM, Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrm3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian Q, Chen W, Cao Y, Cao Q, Cui Y, Li Y, Wu J. Targeting reactive oxygen species in cancer via Chinese herbal medicine. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9240426. doi: 10.1155/2019/9240426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanoni M, Piccinini F, Arienti C, Zamagni A, Santi S, Polico R, Bevilacqua A, Tesei A. 3D tumor spheroid models for in vitro therapeutic screening: a systematic approach to enhance the biological relevance of data obtained. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19103. doi: 10.1038/srep19103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]