Abstract

There is increasing evidence that human movement facilitates the global spread of resistant bacteria and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. We systematically reviewed the literature on the impact of travel on the dissemination of AMR. We searched the databases Medline, EMBASE and SCOPUS from database inception until the end of June 2019. Of the 3052 titles identified, 2253 articles passed the initial screening, of which 238 met the inclusion criteria. The studies covered 30,060 drug-resistant isolates from 26 identified bacterial species. Most were enteric, accounting for 65% of the identified species and 92% of all documented isolates. High-income countries were more likely to be recipient nations for AMR originating from middle- and low-income countries. The most common origin of travellers with resistant bacteria was Asia, covering 36% of the total isolates. Beta-lactams and quinolones were the most documented drug-resistant organisms, accounting for 35% and 31% of the overall drug resistance, respectively. Medical tourism was twice as likely to be associated with multidrug-resistant organisms than general travel. International travel is a vehicle for the transmission of antimicrobial resistance globally. Health systems should identify recent travellers to ensure that adequate precautions are taken.

Keywords: travel, antimicrobial resistance, medical traveller, enteric bacteria, multidrug resistance

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing public health burden that is a serious threat to global health security [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasised the broad impact that AMR will have on human lives, including on health, economic prosperity and other livelihoods [2]. A number of reports have now highlighted the substantially increased levels of AMR bacteria present in many regions of the world [2,3]. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have estimated that there are around 2 million infectious cases in the US annually that are resistant to at least one antimicrobial, resulting in about 23,000 deaths and costing the US health system US$20–$35 billion [4]. Importantly, it has been estimated that this increase in the emergence of AMR organisms can also increase the morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases, as it hampers the ability of antimicrobial drugs to cure infections [3,5]. AMR infections currently result in 700,000 global deaths every year, with associated mortality estimated to claim 10 million lives per year by 2050 [5]. These high mortality rates associated with AMR are expected to cause a cumulative loss of around US$100 trillion to the total world gross domestic product (GDP) in 2050 [5].

The challenges of AMR are complex and multifaceted, with multiple drivers present and interlinked between different hosts and ecologies, including humans, animals, food and the environment [6,7]. These multiple links allow for the movement of by-products of antimicrobial drugs, AMR bacteria, and mobile genetic elements or AMR genes (ARGs), among and between these ecologies, all of which enhance the dissemination of AMR [8]. At the same time, the continuous movement of people across the globe also plays a key role in the emergence and dissemination of AMR organisms [9]. Recently, many studies highlighted the impact of overuse and misuse of antibiotics [10,11], the paucity of antibiotic development [12], and poor access to quality and affordable antibiotics and diagnostics [13,14] in promoting the global transmission of AMR bacteria.

In the past few decades, there has been significant increase in the number of international travellers, mostly of tourists [15]. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has reported that 19% of the world’s population (1.4 billion people) travelled across international borders in 2018 [16]. It is estimated that 11 million individuals have travelled for medical tourism to seek affordable healthcare overseas [17]. In addition, during the past two decades, there has been a very substantial increase in the number of forcibly displaced people globally, particularly those who have been forced to travel from conflict regions in Africa and Asia [18]. Recently, there has been growing evidence that this migration of forcibly displaced people can contribute to the global transmission of AMR [19,20,21].

Historically, globalisation and human migration have profoundly contributed to the emergence and dissemination of infectious diseases [22]. For example, cholera and meningococcal meningitis outbreaks have been associated with international travellers returning from affected (endemic) areas [23,24]. Various international regulations and health protocols have been developed to reduce the burden of such diseases by focusing on vaccination and/or chemoprophylaxis [25,26]; consequently, the risk of travellers returning with colonisation of or infection with AMR organisms has also increased during the past two decades, with the magnitude of this risk varying according to the origin and destinations of travel [9]. The carriage of AMR bacteria following travel to highly endemic AMR regions has been shown to persist for up to 12 months post-travel, which amplifies the risk of introducing AMR organisms into susceptible populations [27].

Here, we systematically review the literature to identify the impact of planned and desired international travel on the global dissemination of AMR in order to better understand the key risk factors that promote the transmission of AMR and to assist health authorities in planning and predicting how to strengthen their health systems in response to the movement of drug-resistant infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

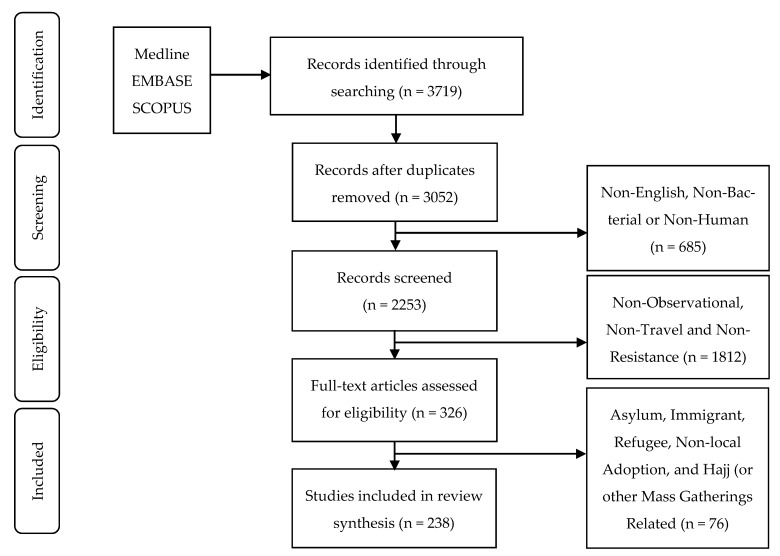

Studies and reports were identified by searching electronic databases, including Medline (PubMed and Ovid), Embase and Scopus, from database inception to the end of June 2019. The search results are presented as per the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28] in Figure 1. We used a combination of key words including: “travel” OR “pilgrim*” OR “Hajj” (also alternative spellings “Hadj” or “Haj”) OR “Olympic” OR “overseas student” OR “international student” OR “immigrant” OR “world cup” OR “mass gathering” OR “crowding” OR “tourism” OR “travel medicine” OR “holiday” AND “drug resistance” OR “methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus” OR “antimicrobial resistan*”. In addition, a manual search was performed on the reference lists of included studies to identify additional potentially relevant papers.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the current systematic review: the methods used for search, identification, screening and the selection process for our review.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Studies that were non-English (language), nonbacterial (organism) or nonhuman (host) were excluded. After screening, studies that did not address travel and AMR were excluded. In addition, studies that had the same or partially the same population with duplicated isolates were included [29,30,31,32] (but have had their isolates numbers adjusted) or completely removed [33,34] (if there was true duplication to the isolate profiles). Isolates were included if there was no duplication of information [35,36]. Reviews, editorials, comments and other non-observational articles were also excluded.

Initially, the intent was to include all contexts of human movement. While developing the manuscript, other systematic reviews were published for some human movement contexts, such as refugees and Hajj [19,37]; therefore, studies with these special contexts of human movement were excluded: asylum seekers, immigrants, refugees, non-local adoption and mass-gathering attendees.

2.3. Study Assessment

Non-randomised studies were assessed based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [38] for cohort and case-control studies. Cross-sectional studies and surveys were assessed with an adapted version of NOS that was used previously by Modesti and colleagues [39]. Moreover, case reports and case series were assessed using a NOS-adapted method that was described by Murad and colleagues [40]. Assessment was based on the respective scoring system, thus setting the maximum score to 9 for cohort and case-control assessments, 10 for cross-sectional studies and surveys, and 5–8 (depending on the study) for case reports and case series article assessment. A grade of “A” was given to randomised control trials (RCTs) of adequate sample size, and it was graded as “B” if the sample size was not adequate. Regarding observational and non-randomised studies, grade “A” was given for 75% or above (in reference to the maximum score), “B” was given for 50–74% and “C” was given for less than a 50% score on a NOS-based or adapted assessment.

2.4. Data Analysis and Visualisations

The total number of studies identified from the nominated databases was 3719 articles, of which 667 were duplicates. By skimming the titles, 799 articles were excluded for not being in English or because they focused on other non-bacterial organisms or on zoonotic hosts. The remaining 2253 articles were screened via their abstracts. Excluding non-observational studies and studies not addressing travel and AMR resulted in 326 eligible studies. The decision to exclude the aforementioned special types of human movement yielded the final 238 studies that were included in this analysis. All phenotypic and molecular confirmations for the acquisition of AMR during travel documented in these studies were included in the analysis. Figures were created using template mapchart.net (https://mapchart.net/), which are licensed under the “Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License” (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/).

3. Results

3.1. AMR Associated with Planned Travel

A total of 30,060 AMR bacterial isolates associated with 17,470 instances of planned international travel (at least one AMR organism documented per instance) was documented in the 238 studies [27,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270] included in this analysis (Table 1). Most studies reported the detection of at least one AMR bacterial species after travel, while travelling or prior to the commencement of travel. There were 2 RCTs, 2 cohort, 13 case-control, 155 cross-sectional (or survey) and 66 case report/series study types. Regarding study assessment, there were 29 studies scored as grade A, 92 scored as B and 177 scored as C based on NOS or assessments adapted from it (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of travel-related antimicrobial resistance isolates, documenting studies and year of publication categorised by decade of isolation: isolates that have isolation time frames that overlap decades were categorised into the earliest decade of this time frame.

| # | Decade Organism was Isolated | Total Travel-Related AMR Isolates | Total Studies Documenting Travel-Related AMR Isolates 1 | Year of Publication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | from | to | |||

| 1 | Before 1990 | 1074 | 6 | 1989 | 1998 | |

| 2 | 1990 | 1999 | 6570 | 32 | 1993 | 2019 |

| 3 | 2000 | 2009 | 16,688 | 91 | 2001 | 2019 |

| 4 | 2010 | 2019 | 5003 | 126 | 2010 | 2019 |

| Total | Until Jun 2019 (inclusive) | 30,060 2 | 238 2 | 1989 | 2019 | |

1 Some studies may document multiple isolates from different decades. Therefore, they may not add up to the total given. 2 Includes 725 isolates with a broad isolation time frame, 1984–2015, from one study; AMR, antimicrobial resistant.

The total pooled population of travellers screened was 632,704, of which 26.33% (n = 166,615) were female and the gender was not documented in 38.22% (241,829). The average representative age of case patients from the pooled studies, when available, was 38.9 years (range 0–103.2 years). A subpopulation of travellers experienced exposure to healthcare systems whilst travelling: hospitalised in, admitted to, repatriated from or seeking treatment (such as medical tourists) from healthcare facilities. Of these 11,089 “medical travellers”, 23.09% (n = 2560) were female and the gender was not documented in 52.51% (n = 5823). The average representative age for medical travellers was 51.4 years (range 0–99 years).

The analysis demonstrated that AMR organisms originated from 139 countries and travelled to 34 countries in total. In general, low- and middle-income countries (124 out of 139) were the source of most AMR organisms, while high-income countries (20 of 34) constituted the major recipients of resistant bacteria.

The countries and regions given in the articles included in the analysis were categorised into 11 groups according to their geographical locations (Table S2). The top regions from which the majority of AMR organisms were sourced or to which people travelled are provided in Tables S3 and S4, respectively. Briefly, 37.12% (n = 11,157; documented in 174 studies), 12.50% (n = 3757; 104 studies) and 10.66% (n = 3205; 59 studies) of the AMR organisms reported in the studied articles originated from Asia, Africa, and Central and South America, respectively (sources). The top source countries of AMR bacteria were India (n = 3602; 70 studies), Kenya (n = 1176; 12 studies), Thailand (n = 1012; 34 studies), Mexico (n = 630; 21 studies), Spain (n = 386; 21 studies), Jamaica (n = 363; 4 studies) and Egypt (n = 292; 28 studies). The source countries of 28.34% (n = 8520; 63 studies) of the AMR organisms reported were either missing or associated with travellers from multiple regions; 50.66% (n = 15,229; 138 studies), 30.81% (n = 9261; 57 studies) and 5.49% (n = 1650; 11 studies) of the AMR organisms reported were in travellers to countries located in Europe, North America and Oceania, respectively. The destination of 9.85% (n = 2962; 4 studies) of the resistant organisms reported were not provided. The largest recipient countries of AMR bacteria included the USA (n = 5449; 40 studies), Canada (n = 3812; 17 studies), the UK (n = 3656; 22 studies), Finland (n = 3382; 10 studies), Spain (n = 1993; 17 studies) and Australia (n = 1650; 11 studies).

3.2. AMR Bacteria Associated with Planned International Travel

The identified resistant organisms comprised 26 bacterial species that mostly included Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp.) and other bacterial species that are commonly associated with hospital- (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumanii) or community-acquired infections (Table S5). The bacterial species were not specified in 17.49% (n = 5258; 29 studies) of the resistant profiles reported, with enteric bacteria constituting 98.90% (n = 5200; 29 studies) of this group as a generalization. Salmonella spp. (20.07%, n = 6032; 63 studies), Shigella spp. (23.06%, n = 6931; 29 studies), E. coli (18.17%, n = 5461; 59 studies), Campylobacter spp. (10.91%, n = 3281; 19 studies) and S. aureus (7.19%, n = 2162; 35 studies) were the most common AMR bacteria reported.

Many of the drug groups for which resistance was reported are clinically important. Resistance to quinolones was documented in 9213 isolates, that to sulphonamides and trimethoprim was documented in 7268 isolates and that to cephalosporins was documented in 2100 isolates (Table S6). Resistance to beta-lactams was seen in 10,474 isolates, which includes resistance to penicillins in 6320 isolates and to carbapenems in 1922 isolates. This means that many of the AMR bacteria detected include species on the WHO list priority pathogen list of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health and resistance to critically important antibiotics [2]. These include carbapenem-resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producers of various Enterobacteriaceae members (e.g., E. coli and Klebsiella spp.), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. Some of the organisms on the WHO list could be detected over a number of decades, with Table 2 listing the detection rates of these nominated organisms by time period and location.

Table 2.

Distribution of the number of AMR isolates by decade for nominated species 1 separated by source.

| Decade | Before 1990 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2019 | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Region | BL/CP | QR | MDR | All AMR | BL/CP | QR | MDR | All AMR | BL/CP | QR | MDR | All AMR | BL/CP | QR | MDR | All AMR | BL/CP | QR | MDR | All AMR |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Sub-Saharan Africa | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4/2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7/1 | 0 | 10 | 19 | 7/1 | 0 | 12 | 21 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 12/11 | 0 | 15 | 28 | 14/13 | 0 | 16 | 31 | |

| Europe | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 2/0 | 0 | 11 | 13 | 2/0 | 0 | 17 | 19 | |

| North America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1/0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| South and Central America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1/0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Oceania | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 0 | 16 | 61 | 12/12 | 12 | 21 | 45 | 13/13 | 12 | 37 | 106 | |

| Campylobacter spp. | Sub-Saharan Africa | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 52 | 0 | 98 | 0/0 | 99 | 0 | 140 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 151 | 0 | 238 |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0/0 | 67 | 0 | 90 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 75 | 0 | 98 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 227 | 0 | 232 | 0/0 | 383 | 1 | 502 | 0/0 | 17 | 1 | 18 | 0/0 | 627 | 2 | 752 | |

| Europe | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 0/0 | 376 | 0 | 402 | 0/0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 466 | 1 | 493 | |

| North America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| South and Central America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 42 | 0 | 76 | 0/0 | 274 | 0 | 299 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 316 | 0 | 375 | |

| Oceania | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1050 | 0/0 | 715 | 0 | 240 | 0/0 | 218 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 933 | 0 | 1309 | |

| Shigella spp. | Sub-Saharan Africa | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 4 | 187 | 337 | 0/0 | 1 | 181 | 426 | 0/0 | 0 | 34 | 42 | 0/0 | 5 | 402 | 805 |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 1 | 60 | 0/0 | 3 | 8 | 66 | 1/0 | 0 | 48 | 70 | 1/0 | 3 | 57 | 196 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 99 | 251 | 434 | 0/0 | 143 | 262 | 1023 | 8/0 | 48 | 127 | 240 | 8/0 | 280 | 640 | 1697 | |

| Europe | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0/0 | 0 | 62 | 67 | 0/0 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 0/0 | 1 | 165 | 177 | |

| North America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 6 | 0 | 180 | 0/0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0/0 | 6 | 3 | 184 | |

| South and Central America | 0/0 | 0 | 31 | 150 | 0/0 | 1 | 57 | 201 | 0/0 | 8 | 53 | 824 | 2/0 | 2 | 28 | 67 | 2/0 | 11 | 169 | 1242 | |

| Oceania | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1/0 | 0 | 4 | 20 | |

| Other | 0/0 | 18 | 37 | 491 | 0/0 | 0 | 27 | 170 | 0/0 | 22 | 104 | 1929 | 1/0 | 1 | 11 | 20 | 1/0 | 41 | 179 | 2610 | |

| Salmonella spp. | Sub-Saharan Africa | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 0/0 | 39 | 27 | 96 | 0/0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0/0 | 44 | 33 | 115 |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 23 | 1 | 25 | 0/0 | 282 | 1 | 287 | 0/0 | 9 | 8 | 20 | 0/0 | 314 | 10 | 332 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0/0 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 0/0 | 220 | 154 | 403 | 0/0 | 1905 | 354 | 2344 | 0/0 | 50 | 35 | 91 | 0/0 | 2290 2 | 1169 3 | 3579 2,3 | |

| Europe | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 24 | 2 | 332 | 0/0 | 70 | 0 | 74 | 0/0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0/0 | 98 | 2 | 410 | |

| North America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| South and Central America | 0/0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0/0 | 14 | 5 | 35 | 0/0 | 1 | 14 | 15 | 0/0 | 18 | 22 | 57 | |

| Oceania | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 0/0 | 9 | 167 | 773 | 0/0 | 200 | 30 | 710 | 0/0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0/0 | 210 | 198 | 1536 | |

| Escherichia coli | Sub-Saharan Africa | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 46/0 | 0 | 9 | 55 | 17/0 | 1 | 29 | 49 | 63/0 | 1 | 42 | 109 |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 13 | 14 | 70/0 | 15 | 9 | 178 | 3/0 | 23 | 3 | 34 | 73/0 | 38 | 25 | 226 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 352/0 | 134 | 41 | 950 | 106/8 | 16 | 68 | 205 | 458/8 | 156 | 116 | 1169 | |

| Europe | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19/0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 71/1 | 23 | 4 | 108 | 90/1 | 23 | 4 | 132 | |

| North America | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35/0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 4/0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 39/0 | 3 | 0 | 70 | |

| South and Central America | 0/0 | 0 | 25 | 203 | 0/0 | 1 | 12 | 75 | 28/0 | 171 | 13 | 1090 | 5/0 | 7 | 12 | 24 | 33/0 | 179 | 62 | 1392 | |

| Oceania | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0/0 | 0 | 0 | 88 | 0/0 | 13 | 0 | 483 | 1/0 | 60 | 108 | 1446 | 84/2 | 32 | 101 | 346 | 85/2 | 105 | 209 | 2363 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | MRSA | MRSA | MRSA | MRSA | MRSA | ||||||||||||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 0 | 1 | 58 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 118 | 64 | 2 | 3 | 176 | |

| North Africa and West Asia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 139 | 0 | 0 | 141 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 155 | 0 | 0 | 157 | |

| Asia (except West Asia) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 705 | 0 | 31 | 737 | 56 | 20 | 23 | 201 | 761 | 20 | 54 | 938 | |

| Europe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 426 | 0 | 1 | 431 | 26 | 0 | 2 | 39 | 452 | 0 | 3 | 470 | |

| North America | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 0 | 1 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 89 | 0 | 1 | 95 | |

| South and Central America | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 88 | 30 | 3 | 0 | 57 | 117 | 3 | 0 | 145 | |

| Oceania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 26 | 1 | 1 | 33 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 12 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 42 | 78 | 14 | 16 | 94 | 117 | 15 | 26 | 148 | |

1 Nominated organisms (Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp. and Staphylococcus aureus). 2 Includes 115 isolates with a broad isolation time frame, 1984–2015. 3 Includes 610 isolates with a broad isolation time frame, 1984–2015; AMR: antimicrobial resistance; All AMR: the total number of isolates with any reported AMR; CP: carbapenem resistance, not exclusive from beta-lactam resistance; BL: beta-lactam resistance, includes carbapenem and/or cephalosporin resistance; MDR: multidrug-resistant organisms, organisms documented as multidrug-resistant, or resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; QR: quinolone resistant, may include co-resistance with beta-lactams or methicillin; Other: unspecified or multiple regions were documented.

Some bacterial species have been the focus of previous studies on travel-related infections. However, some of these species were only occasionally detected in this study, including Mycobacterium spp. (n = 91; 5 studies), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (n = 120; 3 studies), Pseudomonas spp. (n = 44; 12 studies), Burkholderia pseudomallei (n = 5; 5 studies), or those that can cause epidemics (e.g., Vibrio cholerae (n = 5; 3 studies)) (Table S5). Nearly all AMR M. tuberculosis (n = 88; 4 studies) that were associated with travel originated from Africa and are resistant to both isoniazid and rifampicin (n = 86; 2 studies). Travel-associated AMR B. pseudomallei infections were sporadic, with the cases reported usually associated with travel to tropical areas. All travel-related AMR N. gonorrheae isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (n = 119; 2 studies).

3.3. Trends in the Movements of Travel-Associated AMR Bacteria

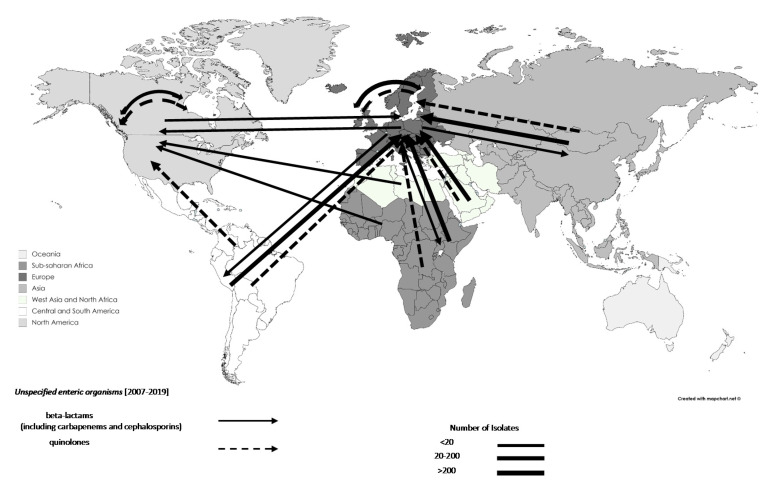

Of the recorded AMR movements associated with travel, 91.83% (n = 27,593; 195 studies) were of enteric bacteria, of which the species was not identified in 18.85% (n = 5200). Of these unidentified enteric bacteria, 2448 were recorded between 1990 and 1999 (47.08%), 415 were recorded between 2000 and 2009 (7.98%), 2337 were recorded between 2010 and 2019 (44.75%), and none were recorded before 1990; the movements of these unidentified enteric bacteria are illustrated in Figure 2. A gradual increase was seen in the number of AMR enteric bacteria overall over time, from 1074 before 1990 (3.89%) to 6427 (1990–1999; 23.29%) and 15,067 AMR enteric bacteria (2000–2009; 54.60%). The majority of these AMR enteric bacteria were associated with travel originating from Asia (35.24%, n = 9725; excluding West Asia), and Central and South America (13.13%, n = 3623). Interestingly, 14.91% (n = 4113; 102 studies) of enteric bacteria associated with travel were categorised as multidrug-resistant (MDR, resistance to three or more antimicrobial classes). The AMR profiles for 37.66% (n = 1549) of MDR enteric bacteria associated with travel were available; 68.11% of MDR enteric bacteria (n = 1055) were resistant to beta-lactams (including carbapenems and cephalosporins) and sulphonamides (including trimethoprim), of which 32.99% (n = 348), 25.78% (n = 272) and 29.38% (n = 310) were co-resistant with amphenicols, quinolones or both, respectively.

Figure 2.

Travel-related antimicrobial resistance for unspecified enteric organisms’ movement, 2007–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

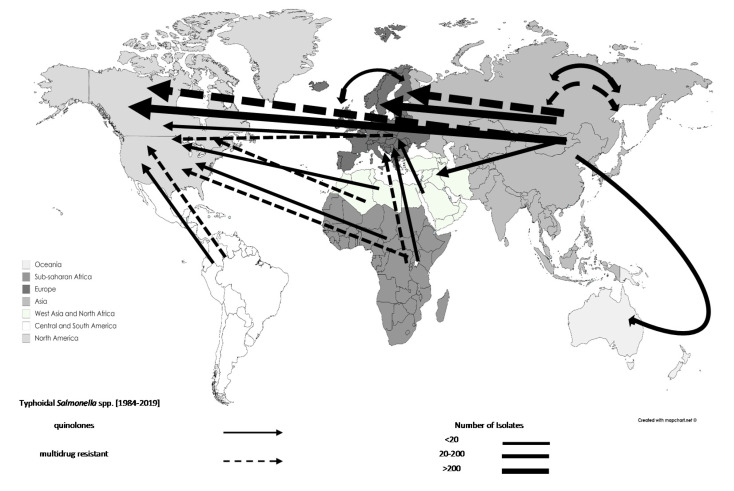

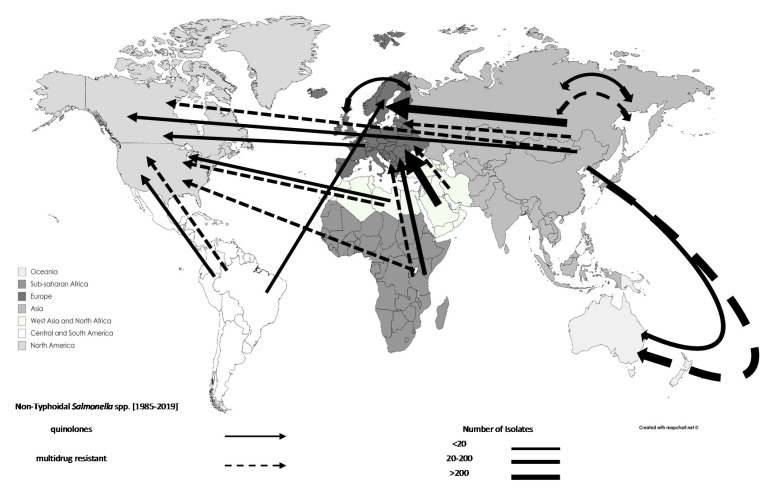

The analysis demonstrated an increase in the total number of resistant Salmonella spp. associated with travel from 1553 in 1990–1999 (25.75%) to 3549 in 2000–2009 (58.84%). Specifically, the rates of reporting quinolone-resistant and MDR Salmonella spp. increased from 283 and 329 in 1990–1999 (9.52% and 22.94%) to 2510 and 417 in 2000–2009 (84.40% and 29.08%) (Table 2). The majority of AMR Salmonella spp. isolates originated from Asia (n = 3579; excluding West Asia). However, an increased number of AMR Salmonella spp. originating from West Asia and North Africa (n = 287), and sub-Saharan Africa (n = 96) was reported during 2000–2009. The movements of AMR Salmonella spp. can be seen in Figure 3, and Figure 4 shows the movements for typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella spp.

Figure 3.

Travel-related antimicrobial resistant typhoidal Salmonella spp. movements, 1984–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

Figure 4.

Travel-related antimicrobial resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella spp. movements, 1990–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

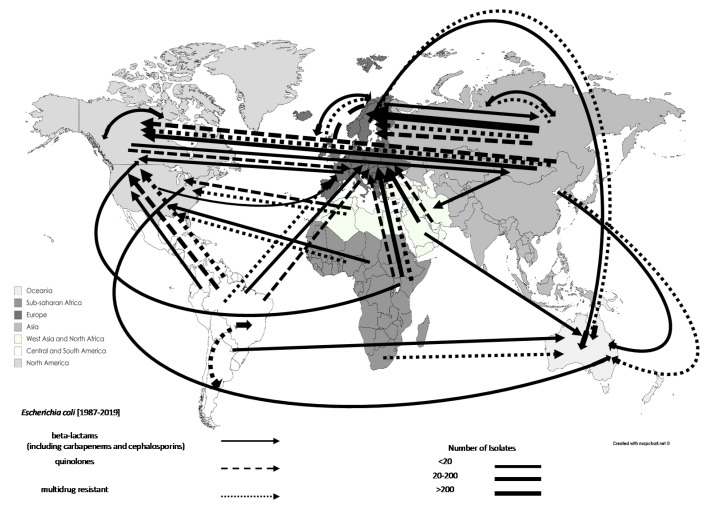

The total number of AMR E. coli isolates associated with travel increased from 591 in 1990–1999 (10.82%) to 3781 in 2000–2009 (69.24%). Specifically, beta-lactam-resistant E. coli isolates started to be documented in 2000–2009 (65.52%), with 551 isolates (Table 2). There were documented increases in the rates of reporting for quinolone-resistant and MDR E. coli over two decades, increasing from 20 and 36 in 1990–1999 (3.96% and 7.79%) to 380 and 180 in 2000–2009 (75.25% and 38.96%), respectively. However, carbapenem-resistant E. coli started to appear in the analysed studies between 2010–2019 (n = 11), with most (72.72%; n = 8) originating from Asia. Overall, AMR E. coli mostly originated from Central and South America (n = 1392; 25.49%), and Asia (n = 1169; 21.41%; excluding West Asia). The documented movements of AMR E. coli in travellers are displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Travel-related antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli transmission, 1987–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

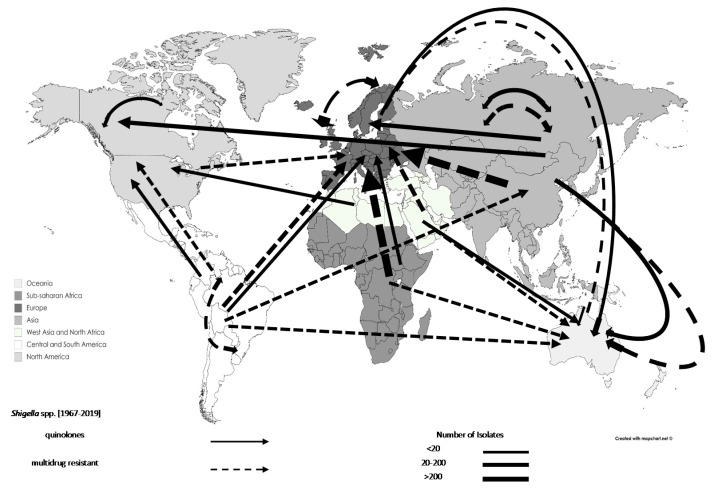

AMR Shigella spp. isolates associated with travel increased from 641 before 1990 (9.25%) to 1302 in 1990–1999 (18.79%) and 4526 in 2000–2009 (65.30%). Specifically, MDR Shigella spp. increased from 68 before 1990 (4.05%) to 623 in 1990–1999 (37.08%) and 670 in 2000–2009 (39.88%). There was a documented increase of quinolone-resistant Shigella spp. from 104 to 183 for the decades 1990–1999 (29.97%) to 2000–2009 (52.74%) (Table 2). Most of the resistant Shigella spp. isolates originated from Asia (n = 1697; 24.48%; excluding West Asia), and Central and South America (n = 1242; 17.92%). However, Europe was the source for 100 and 62 MDR Shigella spp. during the decades 1990–1999 and 2000–2009, respectively. The movements of AMR Shigella spp. can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Travel-related antimicrobial resistant Shigella spp. movements, 1967–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

The documented isolate numbers for AMR Campylobacter spp. isolates that are associated with travel were steady: 1554 in 1990–1999 (47.54%) and 1677 in 2000–2009 (51.30%). However, the rates for quinolone-resistant Campylobacter spp. increased from 419 to 1917 between 1990–1999 (16.30%) and 2000–2009 (74.56%) (Table 2). The majority of any AMR- or quinolone-resistant Campylobacter spp. originated from Asia (n = 752 or n = 627, 23.00% or 24.39% respectively; excluding West Asia).

Travel-associated AMR Klebsiella pneumoniae numbers documented in the literature were low in relation to the corresponding number of studies (n = 187; 27 studies) when compared with other organisms (Table S5). Interestingly, no documentation of AMR K. pneumoniae is present before 2000. Resistant K. pneumoniae numbers increased in the following two decades: with 25 and 57 MDR isolates detected in 2000–2009 (28.74%) and 2010–2019 (65.52%), respectively, and three and 26 carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates detected (10.34% and 89.66%), respectively (Table 2). While the countries of origin were not specified for 56.68% (n = 106) of isolates, the most documented source was Asia (except West Asia): n = 31, 16 and 14 for any AMR, MDR and carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, respectively. The movements of K. pneumoniae isolates associated with travel are illustrated in Figure S1.

3.4. AMR Associated with Exposure to Healthcare Systems

The total number of AMR bacteria isolated from medical travellers was 1342 (49 studies). Beta-lactam resistance (including carbapenem and cephalosporin resistance) was identified in 64.01% (n = 859; 24 studies) of AMR bacteria associated with medical travellers. Moreover, 6.33% (n = 85; 5 studies) of bacterial isolates from medical travellers were quinolone-resistant, of which 29.41% of these (n = 24; 3 studies) were beta-lactam co-resistant. Interestingly, MDR organisms comprised 24.14% (n = 324; 32 studies) of medical traveller bacterial isolates. Hence, medical travellers have around twice the odds of detecting MDR bacterial isolates than other travellers (OR = 1.99, p < 0.001; considering all isolates are independent observations).

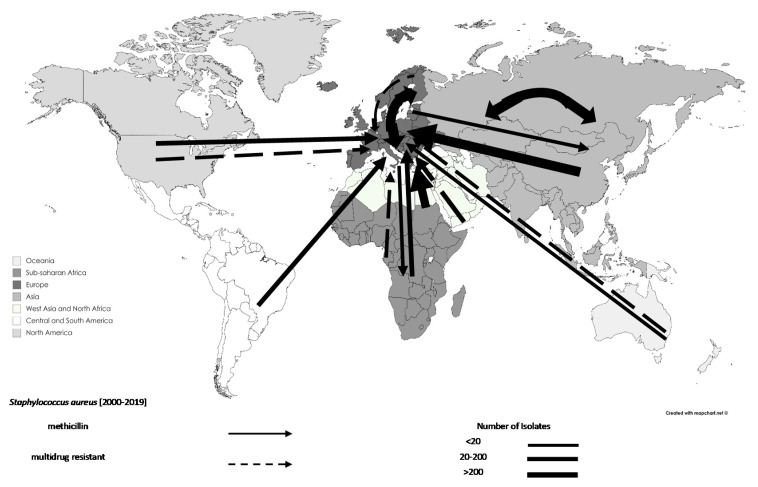

AMR S. aureus isolates associated with travel increased from 12 in 1990–1999 (0.56%) to 1614 in 2000–2009 (74.65%) and 536 in 2010–2019 (24.79%), with no documented cases before 1990. Interestingly, there were 1781 methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates associated with travel, which started to appear between 2000–2009. Most AMR S. aureus isolates originated from Asia (n = 983, 45.47%; excluding West Asia) and Europe (n = 470, 21.74%), of which 77.42% and 95.74% (n = 761 and n = 452, respectively) were MRSA and 4.58% and 0.64% (n = 45 and n = 3, respectively) were MDR, respectively. In addition, 81 MRSA isolates were associated with medical travel, of which 18.52% and 27.16% were from Asia (n = 15; excluding West Asia) and Europe (n = 22), respectively. Interestingly, 18.52% of MRSA cases associated with medical travellers originated from North Africa and West Asia (n = 15). The movements of AMR S. aureus can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Traveling antimicrobial resistance transmission events for Staphylococcus aureus, 2000–2019: data are shown by arrows representing antimicrobial resistant isolate movements, where the arrowhead represents the destination and the base of the arrow represents the source. Thus, double-headed arrows represent movements between the same regions. Different regions are represented by different shades.

Nearly all of the AMR strains of A. baumannii (n = 150; 19 studies) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 43; 11 studies) that were reported in the analysed articles were associated with medical travellers; 26.00% (n = 39) of A. baumannii strains were categorised as MDR, of which 46.15% (n = 18) showed resistance to the combination of beta-lactams, quinolones and aminoglycosides and 33.33% (n = 50) were categorised as beta-lactam-resistant (all were carbapenem-resistant); and 34.88% (n = 15) of the P. aeruginosa strains were categorised as MDR, of which 53.33% (n = 8) showed resistance to the combination of beta-lactams, quinolones and aminoglycosides and 34.88% (n = 15) were categorised as beta-lactam resistant (all were carbapenem- and/or cephalosporin-resistant). Moreover, medical travellers with P. aeruginosa infections usually stayed longer in hospitals when they returned, with a mean hospital length of stay of over 45 days [80]. Furthermore, studies documented that P. aeruginosa with the blaNDM-1 resistance gene were first identified in North America and Europe from medical travellers arriving from Asia and Europe, respectively [103,173].

4. Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance has become a major global health emergency, with human displacement [271], such as that seen for refugees or travellers, as a facilitative factor [19,20]. While the link between AMR and travel was explored previously, few studies have examined this over time and across different regions of the world [6]. Here, we have compiled and analysed the literature recording the detection of travel-related AMR bacteria during the past three decades.

Prior to 1990, a few studies noted a small number of AMR bacteria being isolated, with the most frequently recorded being Shigella spp. from Central and South America or an unspecified location, detected in four studies with 641 isolates. Over time, the frequency of detection of AMR bacteria has increased; however, the number of studies performed has also increased, as has the ease of resistance testing. However, it is clear that there is increasing detection of quinolone-resistant Campylobacter spp., MDR Shigella spp., quinolone-resistant Salmonella spp., and ESBL-producing and quinolone-resistant E. coli isolates.

Examining the trends over time and the geographic regions from which AMR appears to be emerging can help inform on how we should be treating travellers returning from these at-risk regions. From our results, we can see that quinolone resistance in Shigella spp. was first detected in travellers returning from Oceania before 1990 and Asia between 1990–1999. During the same time period, quinolone-resistant Salmonella spp. was also being seen in travellers returning from Asia, with a definite spike in quinolone-resistant and MDR cases of Salmonella between 2000 and 2009. While MDR Shigella spp. was also seen in travellers returning from Asia in 1990–1999, a number of isolates were also associated with West Asia, and North Africa and Europe, with a more distributed picture occurring between 2000 and 2009.

Gastrointestinal (GI) infections or complaints are commonly associated with travel [272]. Diarrhoea is the most common GI symptom associated with travel and is seen in around 60% of GI cases [273]. Travellers’ diarrhoea occurs less frequently with travel from economically developed countries compared with other countries, and bacteria are the most common microbiologically identified aetiology [273,274]. Unsurprisingly, in our study, enteric bacteria also make up the most frequently occurring AMR species associated with travel. Of particular concern is that AMR enteric bacteria, when acting as either a pathogen or coloniser, can transfer their resistance elements to other commensal or pathogenic bacteria present in the gut [275]. We have found that the number of enteric bacterial isolates that are resistant to antibiotics has been increasing over the years, with quinolone resistance in particular being seen more frequently. The WHO raised international concerns over fluoroquinolone-resistant enteric bacteria in their 2014 report [2]. Also echoed in the WHO report is the growing frequency with which MRSA as well as carbapenemase- and ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae are detected in travellers [6]. As many of the travel-related quinolone-resistant enteric bacteria originated from Asia, we suggest that clinicians who see travellers from this region with GI-related illnesses should avoid empirically prescribing ciprofloxacin or any other quinolones.

The best course of treatment for returning travellers who complain of GI symptoms suggesting a bacterial aetiology should now be considered. Based on practical observations from our data, we would caution against or avoid empirical treatment with beta-lactams and quinolones for bacterial GI travel-related illnesses until an AMR profile or culture and sensitivity testing has been performed. For severe cases with a history of travel to Asia, empirical treatment could start with azithromycin (which was also suggested by other studies [272]) and then change to the drug of choice once the AMR results are back. For travellers returning from other destinations, chloramphenicol could also be used as there are still a low number of documented resistant cases globally (Table S7). For travellers arriving from Africa, Central America or South America, it is advisable to avoid prescribing sulphonamides and trimethoprim due to the high levels of resistance seen in bacteria from these regions. Other general guides for returning travellers with bacterial GI infections include setting and related translational medicine evaluation and implementation [272].

Medical travel-related AMR produces a significant risk that resistance may be introduced to a specific part of a health system or even into a complete health system [276]. Some studies mentioned that medical travel-related AMR isolates cause outbreaks within their receiving institutes [88,268] and suggested protocols for such scenarios [47]. There is a lack of documentation for developing economies’ health systems on how they should prepare when receiving such patients. In addition, monitoring medical-related AMR is challenging, as medical tourism has been increasing in frequency, with associated complications often not being reported as linked to travel [277].

There are a number of limitations with this retrospective systematic review. There is significant variation in the ways in which bacterial species are identified (whether via traditional isolation or PCR) and then undergo antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Often, studies do not clearly link isolates or bacterial species to AMR profiles, and such data are not included as Supplementary Information. Travel histories can be vague and incomplete and are often limited to the destination country because this is the one in which the study is performed, with the origin country being that of most recent travel. This reflects the, often retrospective, nature of the studies and clearly does not have pre- and post-travel samples with a clear itinerary in between, limiting the usefulness and precision of these data. AMR bacteria acquired through travel are also not just a risk for the traveller; some isolates may be detected in family members or other close contacts. Finally, MDR bacteria were properly characterised in the majority of studies (n = 101; 1745 isolates) included in our analysis. In a few studies (n = 16 studies; 2440 isolates), the authors identified MDR bacteria based on the number of clinically relevant antibiotics (at least three) to which these isolates exhibited resistance without specifying these drugs.

A major source of bias in this study is the country in which it was carried out. The majority of cases of travel-related AMR were presented in someone travelling to an economically developing region of the world and then returning to their home country (usually economically developed), being the location where they both fell ill and attended facilities available for testing. The majority of global travel is within-country rather than inter-regional. For example, in 2018, in the USA, domestic air travellers were 3.3-fold more common than international travellers [278]. This means that our findings are necessarily skewed towards developing countries being the origin and developed countries being the destination for AMR bacteria. This is unsurprising as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has found that, between 1996–2015, countries with developed economics spend an average of 1.5% of their GDP on research and development, while countries with economies in transition and countries with developing economies only spend 0.6% of their GDP on research and development [279]. The disproportionate number of studies within different regions therefore limits our understanding of the global picture of travel-related AMR.

5. Conclusions

More efforts should focus on the global impacts of travel-related AMR and to encourage studies originating from developing countries. Establishing enteric bacterial AMR profiles for regions with the most traffic to or from may help other healthcare systems address a major part of travel-related AMR. To allow accurate prescription of antimicrobials for patients with complaints that are suspected to be travel-related, hospitalised and inter-healthcare transfers need to be managed in the same way as tertiary-care referrals, with preventive methods on both sides of the journey. Similarly, health authorities may consider the implementation of new guidelines or restrictions for travellers suffering from bacterial infections or those under antibiotic treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Osamah Barasheed for his input in the initial database searching.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/6/1/11/s1, Figure S1. Travel-related antimicrobial resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae movements, 2000–2019, Table S1. List of the included studies in the review, Table S2. List of Countries or regions that are documented in the review, Table S3. Top originating regions for AMR organisms (source), Table S4. Top destination regions for AMR organisms (destination), Table S5. Number of studies and isolates for species that were documented in the analyzed studies, Table S6. Numbers of travel-related AMR isolates documented in 238 studies, up to June 2019 inclusive, categorized by source and isolation time, Table S7. Number of travel-related isolates for enteric organisms with documented AMR component, Table S8. Antimicrobials categories that were included in the analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B., H.R., M.A.E.G. and G.A.H.-C.; methodology, H.B., M.A.E.G. and G.A.H.-C.; formal analysis, K.N.A.P and M.A.E.G.; data curation, H.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B.; writing—review and editing, H.B., M.A.E.G. and G.A.H.-C.; visualization, H.B. and K.N.A.P.; supervision, H.R., M.A.E.G. and G.A.H.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. HM Government; London, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. [(accessed on 1 December 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013–508.pdf.

- 5.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Future Health and Wealth of Nations. HM Government; London, UK: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes A.H., Moore L.S.P., Sundsfjord A., Steinbakk M., Regmi S., Karkey A., Guerin P.J., Piddock L.J.V. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet. 2016;387:176–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fouz N., Pangesti K.N.A., Yasir M., Al-Malki A.L., Azhar E.I., Hill-Cawthorne G.A., Abd El Ghany M. The Contribution of Wastewater to the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment: Implications of Mass Gathering Settings. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;5:33. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khachatourians G.G. Agricultural use of antibiotics and the evolution and transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1998;159:1129–1136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Bij A.K., Pitout J.D.D. The role of international travel in the worldwide spread of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2090–2100. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson J., Iwamoto K., Hoxha I., Ghazaryan L., Abilova V., Cvijanovic A., Pyshnik H., Darakhvelidze M., Makalkina L., Jakupi A., et al. Antimicrobial Medicines Consumption in Eastern Europeand Central Asia—An Updated Cross-National Study and Assessment of Quantitative Metrics for Policy Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;9:1156. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhussupova G., Skvirskaya G., Reshetnikov V., Dragojevic-Simic V., Rancic N., Utepova D., Jakovljevic M. The Evaluation of Antibiotic Consumption at the Inpatient Level in Kazakhstan from 2011 to 2018. Antibiotics. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godman B., Haque M., Islam S., Iqbal S., Urmi U.L., Kamal Z.M., Shuvo S.A., Rahman A., Kamal M., Haque M., et al. Rapid Assessment of Price Instability and Paucity of Medicines and Protection for COVID-19 Across Asia: Findings and Public Health Implications for the Future. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:585832. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.585832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakovljevic M.B., Djordjevic N., Jurisevic M., Jankovic S. Evolution of the Serbian pharmaceutical market alongside socioeconomic transition. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2015;15:521–530. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1003044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miljković N., Godman B., van Overbeeke E., Kovačević M., Tsiakitzis K., Apatsidou A., Nikopoulou A., Yubero C.G., Portillo Horcajada L., Stemer G., et al. Risks in Antibiotic Substitution Following Medicine Shortage: A Health-Care Failure Mode and Effect Analysis of Six European Hospitals. Front. Med. 2020;7:157. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Tourism Organization . UNWTO Annual Report 2017. United Nations World Tourism Organization; Madrid, Spain: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Tourism Organization . UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, January 2019. United Nations World Tourism Organization; Madrid, Spain: 2019. pp. 1–40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson R. Infectious risks of medical tourism. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014;14:680–681. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70861-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Population Statistics: Time Series. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Smalen A.W., Ghorab H., Abd El Ghany M., Hill-Cawthorne G.A. Refugees and antimicrobial resistance: A systematic review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2017;15:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakovljevic M., Al Ahdab S., Jurisevic M., Mouselli S. Antibiotic Resistance in Syria: A Local Problem Turns into a Global Threat. Front. Public Health. 2018;6 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakovljevic M.M., Netz Y., Buttigieg S.C., Adany R., Laaser U., Varjacic M. Population aging and migration–History and UN forecasts in the EU-28 and its east and south near neighborhood–One century perspective 1950–2050. Glob. Health. 2018;14:30. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alirol E., Getaz L., Stoll B., Chappuis F., Loutan L. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:131–141. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore P.S., Harrison L.H., Telzak E.E., Ajello G.W., Broome C.V. Group a meningococcal carriage in travelers returning from Saudi Arabia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1988;260:2686–2689. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03410180094036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mutreja A., Kim D.W., Thomson N.R., Connor T.R., Lee J.H., Kariuki S., Croucher N.J., Choi S.Y., Harris S.R., Lebens M., et al. Evidence for several waves of global transmission in the seventh cholera pandemic. Nature. 2011;477:462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature10392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Global Task Force on Cholera Control . Ending Cholera A Global Roadmap to 2030. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yezli S., Assiri A.M., Alhakeem R.F., Turkistani A.M., Alotaibi B. Meningococcal disease during the Hajj and Umrah mass gatherings. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;47:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcilla M.S., van Hattem J.M., Haverkate M.R., Bootsma M.C.J., van Genderen P.J.J., Goorhuis A., Grobusch M.P., Lashof A.M.O., Molhoek N., Schultsz C., et al. Import and spread of extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): A prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17:78–85. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30319-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurjadi D., Olalekan A.O., Layer F., Shittu A.O., Alabi A., Ghebremedhin B., Schaumburg F., Hofmann-Eifler J., Van Genderen P.J., Caumes E., et al. Emergence of trimethoprim resistance gene dfrG in Staphylococcus aureus causing human infection and colonization in sub-Saharan Africa and its import to Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:2361–2368. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nurjadi D., Friedrich-Janicke B., Schafer J., Van Genderen P.J., Goorhuis A., Perignon A., Neumayr A., Mueller A., Kantele A., Schunk M., et al. Skin and soft tissue infections in intercontinental travellers and the import of multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:567.e1–567.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurjadi D., Schafer J., Friedrich-Janicke B., Mueller A., Neumayr A., Calvo-Cano A., Goorhuis A., Molhoek N., Lagler H., Kantele A., et al. Predominance of dfrG as determinant of trimethoprim resistance in imported Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:1095.e5–1095.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurjadi D., Fleck R., Lindner A., Schafer J., Gertler M., Mueller A., Lagler H., Van Genderen P.J.J., Caumes E., Boutin S., et al. Import of community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Europe through skin and soft-tissue infection in intercontinental travellers, 2011–2016. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy K., Collignon P. Colonisation with Escherichia coli resistant to “critically important” antibiotics: A high risk for international travellers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010;29:1501–1506. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers B.A., Kennedy K.J., Sidjabat H.E., Jones M., Collignon P., Paterson D.L. Prolonged carriage of resistant E. coli by returned travellers: Clonality, risk factors and bacterial characteristics. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:2413–2420. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhanji H., Patel R., Wall R., Doumith M., Patel B., Hope R., Livermore D.M., Woodford N. Variation in the genetic environments of blaCTX-M-15 in Escherichia coli from the faeces of travellers returning to the United Kingdom. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:1005–1012. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins K.L., Mushtaq S., Richardson J.F., Doumith M., De Pinna E., Cheasty T., Wain J., Livermore D.M., Woodford N. In vitro activity of rifaximin against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and other enteropathogenic bacteria isolated from travellers returning to the UK. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2014;43:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leangapichart T., Rolain J.M., Memish Z.A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Gautret P. Emergence of drug resistant bacteria at the Hajj: A systematic review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2017;18:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells G., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. [(accessed on 1 December 2020)]; Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 39.Modesti P.A., Reboldi G., Cappuccio F.P., Agyemang C., Remuzzi G., Rapi S., Perruolo E., Parati G., The European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Cardiovascular Risk in Low Resource Settings Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murad M.H., Sultan S., Haffar S., Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018;23:60–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aardema H., Luijnenburg E.M., Salm E.F., Bijlmer H.A., Visser C.E., Van T.W.J.W. Changing epidemiology of melioidosis? A case of acute pulmonary melioidosis with fatal outcome imported from Brazil. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005;133:871–875. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ackers M.L., Puhr N.D., Tauxe R.V., Mintz E.D. Laboratory-based surveillance of Salmonella serotype Typhi infections in the United States: Antimicrobial resistance on the rise. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000;283:2668–2673. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adelman M.W., Johnson J.H., Hohmann E.L., Gandhi R.T. Ovarian endometrioma superinfected with Salmonella: Case report and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017;4 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ageevets V., Sopova J., Lazareva I., Malakhova M., Ilina E., Kostryukova E., Babenko V., Carattoli A., Lobzin Y., Uskov A., et al. Genetic environment of the blaKPC-2 gene in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate that may have been imported to Russia from Southeast Asia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01856-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ageevets V.A., Partina I.V., Lisitsyna E.S., Ilina E.N., Lobzin Y.V., Shlyapnikov S.A., Sidorenko S.V. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2014;44:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad Hatib N.A., Chong C.Y., Thoon K.C., Tee N.W., Krishnamoorthy S.S., Tan N.W. Enteric Fever in a Tertiary Paediatric Hospital: A Retrospective Six-Year Review. Ann. Acad Med. Singap. 2016;45:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed-Bentley J., Chandran A.U., Joffe A.M., French D., Peirano G., Pitout J.D. Gram-negative bacteria that produce carbapenemases causing death attributed to recent foreign hospitalization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3085–3091. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00297-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Naiemi N., Zwart B., Rijnsburger M.C., Roosendaal R., Debets-Ossenkopp Y.J., Mulder J.A., Fijen C.A., Maten W., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C.M., Savelkoul P.H. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase production in a Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi strain from the Philippines. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2794–2795. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00676-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alcoba-Florez J., Perz-Roth E., Gonzalez-Linares S., Mendez-Alvarez S. Outbreak of Shigella sonnei in a rural hotel in La Gomera, Canary Islands, Spain. Int. Microbiol. 2005;8:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander D.C., Hao W., Gilmour M.W., Zittermann S., Sarabia A., Melano R.G., Peralta A., Lombos M., Warren K., Amatnieks Y., et al. Escherichia coli O104:H4 infections and international travel. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:473–476. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.111281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ali H., Nash J.Q., Kearns A.M., Pichon B., Vasu V., Nixon Z., Burgess A., Weston D., Sedgwick J., Ashford G., et al. Outbreak of a South West Pacific clone Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in a UK neonatal intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012;80:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allyn J., Angue M., Belmonte O., Lugagne N., Traversier N., Vandroux D., Lefort Y., Allou N. Delayed diagnosis of high drug-resistant microorganisms carriage in repatriated patients: Three cases in a French intensive care unit. J. Travel Med. 2015;22:215–217. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allyn J., Coolen-Allou N., De Parseval B., Galas T., Belmonte O., Allou N., Miltgen G. Medical evacuation from abroad of critically ill patients: A case report and ethical issues. Medicine. 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Mashhadani M., Hewson R., Vivancos R., Keenan A., Beeching N.J., Wain J., Parry C.M. Foreign travel and decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility in Salmonella enterica infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:123–125. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.100999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angue M., Allou N., Belmonte O., Lefort Y., Lugagne N., Vandroux D., Montravers P., Allyn J. Risk Factors for Colonization with Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Among Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit After Returning From Abroad. J. Travel Med. 2015;22:300–305. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arai Y., Nakano T., Katayama Y., Aoki H., Hirayama T., Ooi Y., Eda J., Imura S., Kashiwagi E., Sano K. Epidemiological evidence of multidrug-resistant Shigella sonnei colonization in India by sentinel surveillance in a Japanese quarantine station. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2008;82:322–327. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.82.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Artzi O., Sinai M., Solomon M., Schwartz E. Recurrent furunculosis in returning travelers: Newly defined entity. J. Travel Med. 2015;22:21–25. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker K.S., Dallman T.J., Ashton P.M., Day M., Hughes G., Crook P.D., Gilbart V.L., Zittermann S., Allen V.G., Howden B.P., et al. Intercontinental dissemination of azithromycin-resistant shigellosis through sexual transmission: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015;15:913–921. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barlow R.S., Debess E.E., Winthrop K.L., Lapidus J.A., Vega R., Cieslak P.R. Travel-associated antimicrobial drug-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonellae, 2004–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:603–611. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bathoorn E., Friedrich A.W., Zhou K., Arends J.P., Borst D.M., Grundmann H., Rossen J.W. Latent introduction to the Netherlands of multiple antibiotic resistance including NDM-1 after hospitalisation in Egypt, August 2013. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.42.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bengtsson-Palme J., Angelin M., Huss M., Kjellqvist S., Kristiansson E., Palmgren H., Larsson D.G., Johansson A. The Human Gut Microbiome as a Transporter of Antibiotic Resistance Genes between Continents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:6551–6560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00933-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernasconi O.J., Kuenzli E., Pires J., Tinguely R., Carattoli A., Hatz C., Perreten V., Endimiani A. Travelers can import colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, including those possessing the plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5080–5084. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00731-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Birgand G., Armand-Lefevre L., Lepainteur M., Lolom I., Neulier C., Reibel F., Yazdanpanah Y., Andremont A., Lucet J.C. Introduction of highly resistant bacteria into a hospital via patients repatriated or recently hospitalized in a foreign country. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:O887–O890. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blomfeldt A., Larssen K.W., Moghen A., Gabrielsen C., Elstrom P., Aamot H.V., Jorgensen S.B. Emerging multidrug-resistant Bengal Bay clone ST772-MRSA-V in Norway: Molecular epidemiology 2004–2014. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;36:1911–1921. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bochet M., Francois P., Longtin Y., Gaide O., Renzi G., Harbarth S. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in two scuba divers returning from the Philippines. J. Travel Med. 2008;15:378–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bodilsen J., Vammen S., Fuursted K., Hjort U. Mycotic aneurysm caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei in a previously healthy returning traveller. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013202824. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bottieau E., Clerinx J., Vlieghe E., Van Esbroeck M., Jacobs J., Van Gompel A., Van Den Ende J. Epidemiology and outcome of Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobacter infections in travellers returning from the tropics with fever and diarrhoea. Acta Clin. Belg. 2011;66:191–195. doi: 10.2143/ACB.66.3.2062545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bourgeois A.L., Gardiner C.H., Thornton S.A., Batchelor R.A., Burr D.H., Escamilla J., Echeverria P., Blacklow N.R., Herrmann J.E., Hyams K.C. Etiology of acute diarrhea among United States military personnel deployed to South America and west Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;48:243–248. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bowen A., Hurd J., Hoover C., Khachadourian Y., Traphagen E., Harvey E., Libby T., Ehlers S., Ongpin M., Norton J.C., et al. Importation and domestic transmission of Shigella sonnei resistant to ciprofloxacin—United States, May 2014–February 2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015;64:318–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boyd D.A., Mataseje L.F., Pelude L., Mitchell R., Bryce E., Roscoe D., Embree J., Katz K., Kibsey P., Lavallee C., et al. Results from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program for detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. in Canadian hospitals, 2010–2016. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:315–320. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown A.C., Chen J.C., Watkins L.K.F., Campbell D., Folster J.P., Tate H., Wasilenko J., Van Tubbergen C., Friedman C.R. CTX-M-65 Extended-Spectrum b-Lactamase-Producing Salmonella enterica Serotype Infantis, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:2284–2291. doi: 10.3201/eid2412.180500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cabrera R., Ruiz J., Marco F., Oliveira I., Arroyo M., Aladuena A., Usera M.A., Jimenez De Anta M.T., Gascon J., Vila J. Mechanism of resistance to several antimicrobial agents in Salmonella clinical isolates causing traveler’s diarrhea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3934–3939. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3934-3939.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cabrera R., Ruiz J., Sanchez-Cespedes J., Goni P., Gomez-Lus R., Jimenez De Anta M.T., Gascon J., Vila J. Characterization of the enzyme aac(3)-id in a clinical isolate of Salmonella enterica serovar Haifa causing traveler’s diarrhea. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2009;27:453–456. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The Campylobacter Sentinel Surveillance Scheme Collaborators Ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni: Case-case analysis as a tool for elucidating risks at home and abroad. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002;50:561–568. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cha I., Kim N.O., Nam J.G., Choi E.S., Chung G.T., Kang Y.H., Hong S. Genetic diversity of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from Korea and travel-associated cases from east and southeast Asian countries. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;67:490–494. doi: 10.7883/yoken.67.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chan H.L.E., Poon L.M., Chan S.G., Teo J.W.P. The perils of medical tourism: NDM-1-positive Escherichia coli causing febrile neutropenia in a medical tourist. Singap. Med. J. 2011;52:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chan W.W., Peirano G., Smyth D.J., Pitout J.D. The characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae that produce KPC-2 imported from Greece. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;75:317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chatham-Stephens K., Medalla F., Hughes M., Appiah G.D., Aubert R.D., Caidi H., Angelo K.M., Walker A.T., Hatley N., Masani S., et al. Emergence of Extensively Drug-Resistant Salmonella Typhi Infections Among Travelers to or from Pakistan—United States, 2016–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019;68:11–13. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6801a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Christenson B., Ardung B., Sylvan S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Uppsala County, Sweden. Open Infect. Dis. J. 2011;5:107–114. doi: 10.2174/1874279301105010107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chua K.Y.L., Lindsay Grayson M., Burgess A.N., Lee J.Y.H., Howden B.P. The growing burden of multidrugresistant infections among returned Australian travellers. Med. J. Aust. 2014;200:116–118. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohen M.B., Hawkins J.A., Weckbach L.S., Staneck J.L., Levine M.M., Heck J.E. Colonization by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli in travelers with and without diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31:351–353. doi: 10.1128/JCM.31.2.351-353.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cusumano L.R., Tran V., Tlamsa A., Chung P., Grossberg R., Weston G., Sarwar U.N. Rapidly growing Mycobacterium infections after cosmetic surgery in medical tourists: The Bronx experience and a review of the literature. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;63:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dall L.B., Lausch K.R., Gedebjerg A., Fuursted K., Storgaard M., Larsen C.S. Do probiotics prevent colonization with multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae during travel? A randomized controlled trial. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2019;27:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Daniels N.A., Neimann J., Karpati A., Parashar U.D., Greene K.D., Wells J.G., Srivastava A., Tauxe R.V., Mintz E.D., Quick R. Traveler’s diarrhea at sea: Three outbreaks of waterborne enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli on cruise ships. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181:1491–1495. doi: 10.1086/315397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Date K.A., Newton A.E., Medalla F., Blackstock A., Richardson L., McCullough A., Mintz E.D., Mahon B.E. Changing Patterns in Enteric Fever Incidence and Increasing Antibiotic Resistance of Enteric Fever Isolates in the United States, 2008–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:322–329. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dave J., Warburton F., Freedman J., de Pinna E., Grant K., Sefton A., Crawley-Boevey E., Godbole G., Holliman R., Balasegaram S. What were the risk factors and trends in antimicrobial resistance for enteric fever in London 2005–2012? J. Med. Microbiol. 2017;66:698–705. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Day M., Doumith M., Jenkins C., Dallman T.J., Hopkins K.L., Elson R., Godbole G., Woodford N. Antimicrobial resistance in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroups O157 and O26 isolated from human cases of diarrhoeal disease in England, 2015. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:145–152. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Decousser J.W., Jansen C., Nordmann P., Emirian A., Bonnin R.A., Anais L., Merle J.C., Poirel L. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in France, January to May 2013. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.31.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Denis O., Deplano A., De Beenhouwer H., Hallin M., Huysmans G., Garrino M.G., Glupczynski Y., Malaviolle X., Vergison A., Struelens M.J. Polyclonal emergence and importation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains harbouring Panton-Valentine leucocidin genes in Belgium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:1103–1106. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Di Ruscio F., Bjørnholt J.V., Leegaard T.M., Moen A.E.F., De Blasio B.F. MRSA infections in Norway: A study of the temporal evolution, 2006–2015. PLoS ONE. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Drews S.J., Lau C., Andersen M., Ferrato C., Simmonds K., Stafford L., Fisher B., Everett D., Louie M. Laboratory based surveillance of travel-related Shigella sonnei and Shigella flexneri in Alberta from 2002 to 2007. Glob. Health. 2010;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ellington M.J., Ganner M., Warner M., Boakes E., Cookson B.D., Hill R.L., Kearns A.M. First international spread and dissemination of the virulent Queensland community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:1009–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Engsbro A.L., Riis Jespersen H.S., Goldschmidt M.I., Mollerup S., Worning P., Pedersen M.S., Westh H., Schneider U.V. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi in a pregnant traveller returning from Karachi, Pakistan to Denmark, 2019. Eurosurveillance. 2019;24 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.21.1900289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Epelboin L., Robert J., Tsyrina-Kouyoumdjian E., Laouira S., Meyssonnier V., Caumes E., Group M.-G.T.W. High Rate of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli Carriage and Infection in Hospitalized Returning Travelers: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. J. Travel Med. 2015;22:292–299. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Espenhain L., Jørgensen S.B., Leegaard T.M., Lelek M.M., Hänsgen S.H., Nakstad B., Sunde M., Steinbakk M. Travel to Asia is a strong predictor for carriage of cephalosporin resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp. but does not explain everything; Prevalence study at a Norwegian hospital 2014–2016. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2018;7 doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0429-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Espinal P., Miró E., Segura C., Gómez L., Plasencia V., Coll P., Navarro F. First Description of blaNDM-7 Carried on an IncX4 Plasmid in Escherichia coli ST679 Isolated in Spain. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018;24:113–119. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Evans M.R., Northey G., Sarvotham T.S., Hopkins A.L., Rigby C.J., Thomas D.R. Risk factors for ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter infection in Wales. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;64:424–427. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eyre D.W., Town K., Street T., Barker L., Sanderson N., Cole M.J., Mohammed H., Pitt R., Gobin M., Irish C., et al. Detection in the United Kingdom of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae FC428 clone, with ceftriaxone resistance and intermediate resistance to azithromycin, October to December 2018. Eurosurveillance. 2019;24 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.10.1900147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ferstl P.G., Reinheimer C., Jozsa K., Zeuzem S., Kempf V.A.J., Waidmann O., Grammatikos G. Severe infection with multidrug-resistant Salmonella choleraesuis in a young patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2086–2089. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fischer D., Veldman A., Diefenbach M., Schafer V. Bacterial Colonization of Patients Undergoing International Air Transport: A Prospective Epidemiologic Study. J. Travel Med. 2004;11:44–48. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.13647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.FitzGerald R.P., Rosser A.J., Perera D.N. Non-toxigenic penicillin-resistant cutaneous C. diphtheriae infection: A case report and review of the literature. J. Infect. Public Health. 2015;8:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Flateau C., Duron-Martinaud S., Haus-Cheymol R., Bousquet A., Delaune D., Ficko C., Merens A., Rapp C. Prevalence and risk factors for Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-producing- Enterobacteriaceae in French military and civilian travelers: A cross-sectional analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018;23:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Flateau C., Janvier F., Delacour H., Males S., Ficko C., Andriamanantena D., Jeannot K., Merens A., Rapp C. Recurrent pyelonephritis due to NDM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a patient returning from Serbia, France, 2012. Eurosurveillance. 2012;17:20311. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.45.20311-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fleming H., Fowler S.V., Nguyen L., Hofinger D.M. Lactococcus garvieae multi-valve infective endocarditis in a traveler returning from South Korea. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2012;10:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Frickmann H., Wiemer D., Frey C., Hagen R.M., Hinz R., Podbielski A., Köller T., Warnke P. Low Enteric Colonization with Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in Soldiers Returning from Deployments- Experience from the Years 2007–2015. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0162129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]