Abstract

Care coordination is the deliberate organization of patient care activities between two or more participants (including the patient) involved in a person’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services. Organizing care involves the marshalling of personnel and other resources needed to carry out all required patient care activities. It is often managed by the exchange of information among participants responsible for different aspects of care [1]. With an estimated 85% of individuals with Spina Bifida (SB) surviving to adulthood, SB specific care coordination guidelines are warranted. Care coordination (also described as case management services) is a process that links them to services and resources in a coordinated effort to maximize their potential by providing optimal health care. However, care can be complicated due to the medical complexities of the condition and the need for multidisciplinary care, as well as economic and sociocultural barriers. It is often a shared responsibility by the multidisciplinary Spina Bifida team [2]. For this reason, the Spina Bifida Care Coordinator has the primary responsibility for overseeing the overall treatment plan for the individual with Spina Bifida[3]. Care coordination includes communication with the primary care provider in a patient’s medical home. This article discusses the Spina Bifida Care Coordination Guideline from the 2018 Spina Bifida Association’s Fourth Edition of the Guidelines for the Care of People with Spina Bifida and explores care coordination goals for different age groups as well as further research topics in SB care coordination.

Keywords: Spina Bifida, myelomeningocele, care coordination, multidisciplinary care, case management neural tube defects

1. Introduction

Spina bifida or myelomeningocele (MM) is the most common permanently disabling condition in the United States [22] and one of the most complex birth defects compatible with life [23]. Over the past 50 years, advances in medicine have resulted in increased survival of children with Spina Bifida [7]. Many of these people, now adults, require long-term coordinated services from a variety of health care professionals and organizations. Great variability exists among programs with services for people with Spina Bifida and their families. During the past 10 to 20 years, they have had greater access to care coordination, in part due to systems of care consisting of a variety of organizations and agencies that include independent health care professionals and third-party payers, often with different missions. However, despite increased access in some areas, not all receive appropriate care coordination services, especially as they transition from pediatric to adult care [31]. This article discusses the Spina Bifida Care Coordination Guidelines from the 2018 Spina Bifida Association’s Fourth Edition of the Guidelines for the Care of People with Spina Bifida and explores best practice care coordination goals for different age groups as well as further research topics in SB care coordination.

Care coordination is an essential part of the multidisciplinary Spina Bifida care team and vital to improving health care and wellness outcomes. It is recommended, if possible, that Spina Bifida care programs dedicate the necessary financial resources and fund sufficient full-time equivalent staff so that optimal care coordination can be provided by designated, trained, and paid health care professionals. This article in addition to the Spina Bifida Care Coordination Guidelines will also discuss some techniques for measuring the benefits of care coordination activities to patients, and the justification for resource use.

A pediatric medical home is a family-centered partnership within a community-based system that provides uninterrupted care with appropriate payment to support and sustain optimal health outcomes [6]. In their important role of providing a medical home for people with Spina Bifida, primary care providers also have a vital role in the process of care coordination. In concert with the family and the Spina Bifida team [2, 4], care coordination includes communication with the primary care provider in a patient’s medical home [2, 4, 5].

There are very few database studies that demonstrate the benefits of Spina Bifida care coordination programs. Adequate research in SB care coordination would hopefully provide evidence of improved health outcomes, decreased morbidity and mortality, higher quality of life, improved success and independence in adulthood and decreased cost of care for people with Spina Bifida. More research needs to be completed to compile scientific evidence of the effectiveness of care coordination programs to develop a best-practices model of care coordination.

2. Spina bifida care coordination goals and outcomes

The goals of care coordination are the following:

-

•

Gain access to and integrate patient care services and resources

-

•

Link service systems with the family

-

•

Avoid duplication of services and unnecessary cost

-

•

Advocate for improved individual outcomes

Primary Outcomes

-

1.

Maximize the overall health and functioning of individuals living with Spina Bifida throughout the lifespan by improved access to team-based, patient- and family-centered coordinated care for medical, social, educational, equipment needs, and other developmentally relevant services.

Secondary Outcomes

-

1.

Promote comprehensive, coordinated and uninterrupted access to medical, subspecialty, and allied health professional services throughout the lifespan with appropriate communication between the person with Spina Bifida and members of their care team [8].

-

2.

Promote routine screenings and testing congruent with Spina Bifida guidelines for specific secondary conditions.

Tertiary Outcomes

-

1.

Maintain up-to-date coordinated care for individuals living with Spina Bifida to minimize medical complication rates, help control cost of care, and minimize emergency room use and unanticipated hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality [9].

3. Methods

The Care Coordination Guideline for persons living with Spina Bifida across the life span was developed using a combination of literature review and consensus building methodologies [24]. In Phase 1 of the process, clinician and researcher participants were recruited from SBA’s Professional Advisory Council (PAC), through SBA’s contacts with prominent clinicians and scientists in the field and/or from participants in the Spina Bifida World Congress on Research and Care international meetings. A multidisciplinary working group was formed that included, advanced practice Spina Bifida nurse care coordinators, Spina Bifida clinic administrators and physicians. This group via its chair reported to the Spina Bifida Health Care Guideline Steering Committee who in turn reported to the Spina Bifida Association Medical Director. Members of the Care Coordination working group agreed upon primary, secondary and tertiary outcomes, defined as the ideal end-result of best practices care coordination. The working group then devised a list of “clinical questions” that, if answered through evidence-based research, would provide guidance on how best to provide care coordination for people with Spina Bifida and achieve best outcomes. In addition, feedback was given and the vetting of the clinical questions was performed by adults with Spina Bifida along with parents of children with Spina Bifida recruited by the SBA and its chapters [24].

Phase 2 of the Care Coordination Guidelines development included an extensive literature review. Databases searched included Medline, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CDC library, PsycInfo, JSTOR, Google Scholar, CINAHL, and ProQuest. The articles that met inclusion criteria and were most relevant to the care coordination topic and clinical questions were forwarded to all working group members for review [24].

Phase III of care coordination guidelines development began with the working group drafting the guidelines using a pre-defined template containing five sections (Introduction, Outcomes, Clinical Questions, Guidelines, and Research Gaps). The introduction summarized the importance of the topic and listed outcomes and clinical questions. Also, a list of recommendations and guidelines for care was developed, based on the clinical questions that were answered by the literature or clinical consensus of experts. Finally, research gaps which were clinical questions that were not answered well by the literature or clinical consensus were identified. The consensus building methodology has been outlined previously in the methodology manuscript by Dicianno [24].

The SB Care Coordination Guidelines were presented by the working group chair at a face-to-face meeting of all guideline professional participants on March 15, 2017. The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was used to solicit constructive feedback from participants. This technique has been used in the development of guidelines for the care of individuals with other conditions and allows for expert opinion to be included for aspects of care for which medical evidence does not exist or is not robust. The Care Coordination Guidelines was reviewed by six experts in the field for consistency, redundancy, disability-sensitive language, and clarity. It was also reviewed by the SBA Steering Committee chairs for actionable and concise language, use of consistent semantics and ICF terminology, and sufficient justification with clinical consensus or references. Suggested edits were sent back to the working group for revision and then sent back to SBA for final proofreading and copyediting by SBA staff and SBA’s Medical Director prior to publication on the SBA web site:

Spina Bifida Association. Guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida. 2018. https://www.spinabifidaa ssociation.org/guidelines/.

4. Results

The clinical questions that led to the specific care coordination guidelines are organized by age group, reflecting the changing nature of care coordination goals over time as a person with spina bifida ages. The early age group clinical questions (Table 1) often focus on communication about organizing multidisciplinary care to optimize outcomes, minimize medical complications, and help the family cope with the new diagnosis, including during the prenatal period. As the child ages, the clinical questions become more focused toward care coordination goals of adult independence, and transitioning care to adult providers. For all age groups, there are clinical questions related to the barriers that exist for effective care coordination, and what aspects of care coordination families and individuals find most helpful.

Table 1.

Clinical questions that informed the spina bifida care coordination guidelines

| Age group (from guidelines) | Clinical questions |

|---|---|

| 0–11 months |

|

| 1–2 years 11 months |

|

| 3–5 years 11 months |

|

| 6–12 years 11 months |

|

| 13–17 years 11 months |

|

|

Table 1, continued | |

|---|---|

| Age group (from guidelines) | Clinical questions |

|

|

| 18+ years |

|

The specific Spina Bifida care coordination guidelines (Table 2) evolve as the child with Spina Bifida ages. Starting in the NICU, the early age group care coordination guidelines focus on family education about the condition of Spina Bifida and coping with the new diagnosis. In addition, efforts focus on coordination of the multiple surgical subspecialty care services needed including orthopedics, urology and neurosurgery. As the child ages through the toddler and preschool years, it is recommended that the care coordinator monitor the availability and progress of early intervention services such as PT, OT and speech. Ideally, the care coordinator is also involved with the IEP (Individual Educational Plan 504 plan) process and transition to school. This process continues as the child progresses through primary and secondary school. The care coordinator monitors the progress through school and helps to assist families when problems with school functioning occur. When necessary, this includes engagement with teachers, school principals, administration, and nursing staff.

Table 2.

Spina bifida care coordination guidelines

| Age group | Guidelines | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 0–11 months |

|

[9, 10] |

|

[10, 11] | |

|

Clinical consensus, Latex and Latex Allergy in Spina Bifida Guidelines, Neurosurgery Guidelines, Orthopedics Guidelines, Urology Guidelines | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

| [2, 12] | ||

|

[4, 11] | |

|

Clinical consensus, Appendix: Early Intervention Services, Individualized Educational Plans (IEP) and 504 Plans [10] | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines |

The promotion of independence and self-management is a recurring theme throughout most age groups in the care coordination guidelines. This process begins in preschool with greater emphasis as the child ages to adolescence. There is encouragement for children with Spina Bifida to participate in age appropriate peer activities outside of the school setting. During adolescence, there are guidelines for specific topics relevant to this age group including sexuality, substance use, mental health, driver education and preparation for college.

Finally, for the adult age group, care coordination guidelines focus on having a successful transition to adult care and independence. This includes the care coordinator taking an inventory of self-care skills. The care coordinator should know about the adult programs and Spina Bifida care providers in their area and be able to educate families on care plans when no adult multidisciplinary Spina Bifida clinics exist. It is recommended that the care coordinator be able to assist families with referrals to employment or vocational training programs when appropriate. In addition, for those living with Spina Bifida and significant intellectual disability, the care coordinator should be able to assist with the conservatorship process when appropriate.

Certain SB care coordination guidelines were relevant and included in all age groups. An example is the importance of the care coordinator using two-way communication with families, acting in partnership and communicating regularly with the person’s primary care physician. For all age groups it is recommended that the Spina Bifida Care Coordinator should serve as the lead contact person and information provider for the Spina Bifida clinic and monitor individual needs and prescriptions for durable medical equipment, supplies, and medications as needed. In addition, for all age groups, it is appropriate that the care coordinator assist with insurance authorizations as well as other services such as SSI social security, etc. Mental health needs and services are part of the care coordination guidelines including screening and referral for mental health treatment when necessary. The Spina Bifida care coordination guidelines for are presented below (Table 2). For each guideline, when published evidence exists, the associated reference is cited next to the guidelines. For those guidelines for which no published evidence exists, clinical consensus of the working group or other SB care guidelines are cited.

|

Table 2, continued | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age group | Guidelines | Evidence |

| 1–2 years 11 months |

|

Clinical consensus [12] |

|

Clinical consensus, Family Functioning Guidelines, Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

|

[13] | |

|

[12] | |

|

[4, 11] | |

|

Clinical consensus, Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

|

Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines | |

| 3–5 years 11 months |

|

Clinical consensus, Bowel Function and Care Guidelines, Mental Health Guidelines, Mobility Guidelines, Neuropsychology Guidelines, Skin (Integument) Guidelines, Urology Guidelines |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

[2, 12] | |

|

[4, 11, 12] Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines | |

|

[11] | |

|

Table 2, continued | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age group | Guidelines | Evidence |

| 6–12 years 11 months |

|

Clinical consensus, Bowel Function and Care Guidelines, Mental Health Guidelines, Mobility Guidelines, Neuropsychology Guidelines, Skin (Integument) Guidelines, Urology Guidelines |

|

Clinical consensus, Appendix: Early Intervention Services, Individualized Educational Plans (IEP) and 504 Plans [13] | |

|

[2, 12] | |

|

Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines | |

|

[14, 15] Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

|

[4, 11] | |

|

[11, 16] | |

| 13–17 years 11 months |

|

Clinical consensus, Bowel Function and Care Guidelines, Mental Health Guidelines, Mobility Guidelines, Neuropsychology Guidelines, Skin (Integument) Guidelines, Urology Guidelines |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

[2, 12] | |

|

[4, 11] | |

|

Table 2, continued | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age group | Guidelines | Evidence |

|

[17, 18, 19]Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

|

[15, 20, 21] Self-Management and Independence Guidelines, Transition Guidelines | |

|

Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

Clinical consensus, Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

| 18+ years |

|

[15] Transition Guidelines |

|

[16] Clinical consensus, Self-Management and Independence Guidelines | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

Clinical consensus | |

|

[2, 12, 17] Mobility Guidelines, Neurosurgery Guidelines, Orthopedics Guidelines, and Urology Guidelines | |

|

Table 2, continued | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age group | Guidelines | Evidence |

|

Clinical consensus, Mental Health Guidelines | |

|

[15] | |

|

[17, 20] Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine Guidelines, Mobility Guidelines, Neurosurgery Guidelines, Nutrition, Metabolic Syndrome, and Obesity Guidelines, Orthopedics Guidelines, Urology Guidelines | |

5. Discussion

The Spina Bifida Care Coordination Guidelines will be updated as new data become available. As such, these should be considered as guidelines and options, not standards of care. It is hoped that these Care Coordination Guidelines will not only guide health care providers but also patients and families, so that they can have the best and most scientifically-based care and treatments throughout their ever-longer and higher-quality lives. Care coordination is an essential component of health care delivery [25]. At the core, patient- and family-centered care within a medical home is a foundational component; outcomes are optimized when there is cross-sector collaboration among the multiple medical systems and providers, community services, and support agencies with whom families and those with Spina Bifida interact. While effective care coordination typically requires dedicated paid personnel, care coordination activities are not the sole responsibility of a single individual or provider [26]. Rather, all people who interact with patients and families have a role to play. The second concept, in the context of patient- and family-centered care, is that for people with Spina Bifida, care may be provided via a medical neighborhood with team-based care [27, 28]. Within this framework is co-management with defined roles, data sharing, and collaborative care protocols among primary care, subspecialty care, and community-based services. Full implementation of these guidelines to optimize outcomes cannot rest with the clinic alone. Indeed, guidance provided on many topics should be implemented through primary care providers and efforts of community services. While the Spina Bifida clinic may direct the overall health care planning in many cases, optimal care is best achieved as a partnership between families and people with Spina Bifida, primary and subspecialty care providers, health systems, and community services.

During the process to create the Care Coordination Guidelines, several gaps in the research literature, and opportunities for future studies, were identified. For example, what database studies demonstrate the benefits of Spina Bifida care coordination programs, to improve health outcomes, decrease morbidity and mortality, promote higher quality of life, improve success and independence in adulthood, and decrease cost of care? What research exists regarding the effectiveness of care coordination programs to develop a best-practice model of care coordination? How do the roles and responsibilities of the Spina Bifida Care Coordinator evolve over time with aging? What are the common barriers to creating an effective patient-centered care coordination program within the multidisciplinary Spina Bifida clinic? Examples of barriers could include insufficient training, logistical difficulties, and unavailability of personnel and community resources. What aspects of a care coordination program do families and individuals find most helpful and improve their perception of the care they receive? What evidence exists to show the success of the care coordination program in improving overall health? What literature is available to support optimal teaching and education of children and their caregivers throughout the lifespan to maximize early independence? What is the Spina Bifida Care Coordinator’s role in educating and bringing adult providers into the care team to ensure seamless transition of care, and in developing transition goals and processes for people as they age out of the pediatric system to ensure continuity of care?

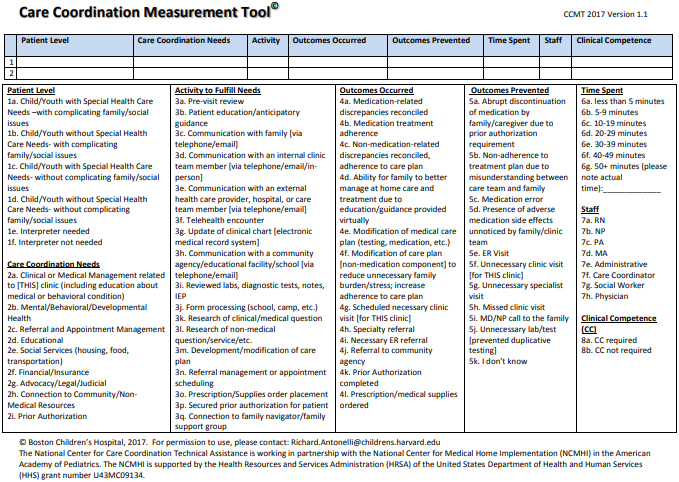

To begin the process of addressing the research gaps in Spina Bifida care coordination and to develop methods to effectively measure the results of care coordination intervention services, the Spina Bifida Association (SBA) began a joint project with the National Center for Care Coordination Technical Assistance (NCCCTA) at Boston Children’s Hospital [29]. The goals of the SBA/NCCCTA partnership were to involve SBA clinical partners in the adaptation and implementation the Pediatric Integrated Care Survey (PICS) and/or the Care Coordination Measurement Tool (CCMT) from the National Center for Care Coordination Technical Assistance. Both tools are intended to collect care coordination data that leads to outcomes of improved patient experience, health outcomes, reduced cost, and provider experience. This data can be used to justify the costs associated with quality care coordination services and measure the benefits of those services. Many challenges exist for families that receive care in multidisciplinary Spina Bifida clinics, including fragmentation of care, lack of coordination of services and supplies, reimbursement for services and equipment by insurance, and the necessary resources to provide care coordination. This contributes to poor health outcomes, less than optimal family experience, and use of high cost, unnecessary emergency services. The Pediatric Integrated Care Survey (PICS) tool is a family experience measure of care integration consisting of 19 validated experience questions plus health care status/utilization and demographic questions [30]. The PICS tool allows ascertainment of how patient/family consumers experience these benefits and their perceptions of the quality of the care coordination programs within their Spina Bifida Center. The Care Coordination Measurement Tool (CCMT) is a care coordination value capture tool. The CCMT (Fig. 1) can be used by multiple disciplines within the Spina Bifida clinic including nurses, social workers, patient navigators, case managers primary and subspecialty care providers. The CCMT is designed to be adapted to the specific care coordination data collection and Quality Improvement needs of individual SB clinics. The CCMT enables care providers to record the types of encounters that necessitate care coordination activities including complexity level of patient requiring care coordination, activities performed, outcomes that occurred and were prevented as a result of successful care coordination. Already several SBA designated clinical care partners have embarked on pilot studies and quality improvement projects using the tools from the National Center for Care Coordination Technical Assistance to improve the care coordination experience of families within their clinics. We look forward to the publication of the results from these clinics so that the current Spina Bifida Care Coordination Guidelines can be updated in the future using the best available scientific evidence.

Figure 1.

CCMT care coordination measurement tool [29].

Acknowledgments

This edition of the Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine includes manuscripts based on the most recent “Guidelines For the Care of People with Spina Bifida,” developed by the Spina Bifida Association. Thank you to the Spina Bifida Association for allowing the guidelines to be published in this forum and making them Open Access.

The Spina Bifida Association has already embarked on a systematic process for reviewing and updating the guidelines. Future guidelines updates will be made available as they are completed.

Executive Committee

-

•

Timothy J. Brei, MD, Spina Bifida Association Medical Director; Developmental Pediatrician, Professor, Seattle Children’s Hospital

-

•

Sara Struwe, MPA, Spina Bifida Association President & Chief Executive Officer

-

•

Patricia Beierwaltes, DPN, CPNP, Guideline Steering Committee Co-Chair; Assistant Professor, Nursing, Minnesota State University, Mankato

-

•

Brad E. Dicianno, MD, Guideline Steering Committee Co-Chair; Associate Medical Director and Chair of Spina Bifida Association’s Professional Advisory Council; Associate Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

-

•

Nienke Dosa MD, MPH, Guideline Steering Committee Co-Chair; Upstate Foundation Professor of Child Health Policy; SUNY Upstate Medical University

-

•

Lisa Raman, RN, MScANP, MEd, former Spina Bifida Association Director, Patient and Clinical Services

-

•

Jerome B. Chelliah, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Additional acknowledgements

-

•

Julie Bolen, PhD, MPH, Lead Health Scientist, Rare Disorders Health Outcomes Team, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

•

Adrienne Herron, PhD Behavioral Scientist, Intervention Research Team, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

•

Judy Thibadeau, RN, MN, Spina Bifida Association Director, Research and Services; former Health Scientist, National Spina Bifida Program, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Funding

The development of these Guidelines was supported in part by Cooperative Agreement UO1DD001077, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- [1]. Butler M, Kane RL, Larson S, Moore Jeffery M, Grove M. Quality Improvement Measurement of Outcomes for People With Disabilities: Closing the Quality Gap: Revisiting the State of the Science. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2012; Oct; 208(7): 1-112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Brustrom J, Thibadeau J, John L, Liesmann J, Rose S. Care coordination in the spina bifida clinic setting: current practice and future directions. J Pediatr Health Care. Jan-Feb 2012; 26(1): 16-26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Ziring PR, Brazdziunas D, Cooley WC, Kastner TA, Kummer ME, Gonzalez de Pijem L et al. Care Coordination: Integrating Health and Related Systems of Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 1999. Oct; 104(4Pt 1): 978-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Liptak GS, Revell GM. Community physician’s role in case management of children with chronic illnesses. Pediatrics. 1989. Sep; 84(3): 465-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Van Cleave J, Okumura MJ, Swigonski N, O’Connor KG, Mann M, Lail JL. Medical Homes for Children With Special Health Care Needs: Primary Care or Subspecialty Service? Acad Pediatr. May-Jun 2016; 16(4): 366-72. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002. Jul; 110(1 Pt 1): 184-6. 12093969 [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Oakeshott P, Hunt GM, Poulton A, Reid F. Expectation of life and unexpected death in open spina bifida: a 40-year complete, non-selective, longitudinal cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010. Aug; 52(8): 749-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Miller AR, Condin CJ, McKellin WH, Shaw N, Klassen AF, Sheps S. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009. Dec 21; 9: 242. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. West C, Brodie L, Dicker J, Steinbeck K. Development of health support services for adults with spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 33(23-24): 2381-8. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.568664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Dunleavy MJ. The role of the nurse coordinator in spina bifida clinics. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007. Nov 26; 7: 1884-9. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SKM, Simon TD, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011. Mar; 127(3): 529-38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Dicianno BE, Fairman AD, Juengst SB, Braun PG, Zabel TA. Using the spina bifida life course model in clinical practice: an interdisciplinary approach. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010. Aug; 57(4): 945-57. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Burke R, Liptak GS. Providing a primary care medical home for children and youth with spina bifida. Pediatrics. 2011. Dec; 128(6): e1645-57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Oakeshott P, Hunt GM, Poulton A, Reid F. Expectation of life and unexpected death in open spina bifida: a 40-year complete, non-selective, longitudinal cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010. Aug; 52(8): 749-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists’ perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009. Feb; 123(2): 417-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Dunleavy MJ. The role of the nurse coordinator in spina bifida clinics. Scientific World Journal. 2007. Nov 26; 7: 1884-9. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Binks JA, Barden WS, Burke TA, Young NL. What do we really know about the transition to adult-centered health care? A focus on cerebral palsy and spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007. Aug; 88(8): 1064-73. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. West C, Brodie L, Dicker J, Steinbeck K. Development of health support services for adults with spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 33(23-24): 2381-8. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.568664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Stille C, Antonelli R. Coordination of care for children with special health care needs. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2004; 16: 700-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Mukherjee S. Transition to adulthood in spina bifida: changing roles and expectations. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007. Nov 26; 7: 1890-5. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Ridosh M, Braun P, Roux G, Bellin M, Sawin K. Transition in young adults with spina bifida: a qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev. 2011. Nov; 37(6): 866-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Spina Bifida Association of America. What Is Spina Bifida? 2020.

- [23]. Liptak GSE. Evidence-Based Practice in Spina Bifida: Developing a Research Agenda. Washington, DC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Dicianno BE, Beierwaltes P, Dosa N, Raman L, Chelliah J, Struwe S, et al. Scientific methodology of the development of the guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida: an initiative of the Spina Bifida Association. Disabil Health J. 2020. Apr; 13(2): 100816. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Council on Children with Disabilities and Medical Home Implementation Project Advisory Committee. Patient-and Family-Centered Care Coordination: A Framework for Integrating Care for Children and Youth Across Multiple Systems. Pediatrics. 2014. May; 133(5): e1451-60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Kuo DZ, McAllister JW, Rossignol L, Turchi RM, Stille CJ. Care Coordination for Children With Medical Complexity: Whose Care Is It, Anyway? Pediatrics. 2018. Mar; 141(Suppl 3): S224-S232. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1284G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Kuo DZ, Houtrow AJ. Recognition and Management of Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2016. Dec; 138(6): e20163021. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Katkin JP, Kressly SJ, Edward AR, Perrin JM, Kraft CA, Richerson JE, et al. Guiding Principles for Team-Based Pediatric Care. Pediatrics. 2017. Aug; 140(2): e20171489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. National Center for Care Coordination Technical Assistance. Boston Children’s Hospital. Available from: https://www.childrenshospital.org/integrated-care-program/national-center-for-care-coordination-technical-assistance.

- [30]. Ziniel SI, Rosenberg HN, Bach AM, Singer SJ, Antonelli RC. Validation of a Parent-Reported Experience Measure of Integrated Care. Pediatrics. 2016. Dec; 138(6): e20160676. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Spina Bifida Association. Guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida. 2018. Available from: https//www.spinabifidaassociation.org/guidelines/.