Abstract

Common rust (CR) caused by Puccinia sorghi Schwein is one of the major foliar diseases of maize (Zea mays L.) in Eastern and Southern Africa. This study was conducted to (i) evaluate the response of elite tropical adapted maize inbred lines to Puccinia sorghi and identify resistant lines (ii) examine associations between CR disease parameters and agronomic traits, and (iii) assess the genetic diversity of the inbred lines. Fifty inbred lines were evaluated in field trials for three seasons (2017–2019) in Uganda under artificial inoculation. Disease severity was rated on a 1–9 scale at 21 (Rust 1), 28 (Rust 2), and 35 (Rust 3) days after inoculation. Area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated. The genetic diversity of the lines was assessed using 44,975 single nucleotide polymorphism markers. Combined ANOVA across seasons showed significant (P < .001) line mean squares for the three rust scores and AUDPC. Heritability was high for Rust 2 (0.90), Rust 3 (0.83), and AUDPC (0.93). Of the 50 lines, 12 were highly resistant to CR. Inbred lines CKL1522, CKL05010, and CKL05017 had significantly lower Rust 3 scores and AUDPC compared to the resistant check CML444 and are potential donors of CR resistance alleles. The genetic correlations between CR disease resistance parameters were positive and strong. A neighbor‐joining (NJ) tree and STRUCTURE suggested the presence of three major groups among the lines, with lines highly resistant to CR spread across the three groups. The genetic diversity among the highly resistant lines can be exploited by recycling genetically distant lines to develop new multiple disease resistant inbred lines for hybrid development and deployment.

Abbreviations

- AD

days to anthesis

- CIMMYT

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

- EA

ear aspect

- EH

ear height

- ESA

eastern and southern Africa

- GLS

gray leaf spot

- IITA

International Institute of Tropical Agriculture

- MSV

maize streak virus

- NCLB

northern corn leaf blight

- PA

plant aspect

- PH

plant height

- SD

days to silking

- SSA

sub‐Saharan Africa.

1. INTRODUCTION

Maize (Zea mays L.) is grown on approximately 18.9 million hectares, with production of 41.8 million tons in eastern and southern Africa (ESA) (FAOSTAT, 2018). Maize is a source of both carbohydrates and protein for millions of people in ESA. Maize production in this region is affected by several biotic stresses including insect pests (Goergen, Kumar, Sankung, Togola, & Tamò, 2016; Kfir, Overholt, Khan, & Polaszek, 2002; Mugo et al., 2004), virus and foliar diseases (Kyetere et al., 1999; Mahuku et al., 2015; Marenya et al., 2018; Martin & Shepherd, 2009; Prasanna et al., 2020; Wangai et al., 2012), and parasitic weeds especially Striga hermonthica (Kanampiu et al., 2018). The major foliar diseases of economic importance in the mid‐altitude and highland ecologies of ESA are northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) caused by Exserohilum turcicum (Pass.) Leonard & Suggs (Pratt et al., 2003; Vivek et al., 2010), gray leaf spot (GLS) caused by Cercospora zeae‐maydis Tehon & Daniels (Asea et al., 2002; Bigirwa, Pratt, Adipala, & Lipps, 2001; Menkir & Ayodele, 2005; Ward, Stromberg, Nowell, & Nutter, 1999), and common rust caused by Puccinia sorghi Schwein (CABI, 2019; Fininsa & Yuen, 2001; Vivek et al., 2010).

Common rust (CR) of maize is widely distributed in temperate (Gingera, Davis, & Groth, 1994; Pataky & Tracy, 1999) and subtropical and tropical (Bekeko, 2019; Darino et al., 2016; Pratt & Gordon, 2006; Vivek et al., 2010) maize growing regions of the world. Puccinia sorghi is an obligate parasite (Anderson, Tyler, & Pryor, 1992; Pryor, 1994). Common rust disease epidemics are characterized with short latency periods of about five to ten days at temperatures of 15–25 °C and are more common at a relative humidity of at least 98% (Hooker, 1985; Pataky & Tracy, 1999). Common rust leads to loss of photosynthetic leaf area, chlorosis and premature leaf senescence, resulting in incomplete grain filling and poor yields, and low grain quality (Groth, Zeyen, Davis, & Christ, 1983a; Roelfs & Bushnell, 1985). Grain yield losses ranging from 12–75% have been reported for different maize genotypes (Dey et al., 2012; Groth et al., 1983a; Kim & Brewbaker, 1976; Shah & Dillard, 2006). Pataky (1987) estimated a 6.5% yield loss for every 10% of leaf area diseased by CR.

Several options to control CR have been proposed including use of fungicides (Pataky & Headrick, 1989; Wegulo, Rivera‐C, Martinson, & Nutter, 1998; Wright, Parkerb, Van Tilburg, & Hedderley, 2014), foliar fertilizer (Reuveni, Agapov, & Reuveni, 1994), biocontrol agents (Dey et al., 2013; Sartori et al., 2017) and resistant varieties (Headrick & Pataky, 1987; Pataky & Headrick, 1989; Pataky & Eastburn, 1993; Abedon & Tracy, 1998; Gingera et al., 1994). The development and deployment of resistant maize genotypes is the most ecologically friendly strategy to minimize the effects of P. sorghi, reduce the cost and adverse effects of fungicides, and significantly contribute to increased grain yield (Lübberstedt et al., 1998). Climate change projections have indicated that some areas of Africa will likely experience an increased risk of occurrence of both common and southern (Puccinia polysora Underw.) rust by 2050 (Ramirez‐Cabral, Kumar, & Shabani, 2017). Hence, to mitigate the potential risks, there is a need to introgress resistance to CR in inbred lines adapted to the different agro‐ecologies where the disease is a challenge. Both race specific (Hu & Hulbert, 1996; Hulbert, 1997; Hulbert, Lyons, & Bennetzen, 1991) and partial resistance (Gingera et al., 1994; Randle, Davis, & Groth, 1984) to CR have been reported. Several studies have identified quantitative trait loci (QTL) for resistance to CR on different chromosomes in different germplasm (Brown, Juvik, & Pataky, 2001; Kerns, Dudley, & Rufener, 1999; Lübberstedt et al., 1998; Olukolu, Tracy, Wisser, De Vries, & Balint‐Kurti, 2016; Rossi, Ruiz, Bonamico, & Balzarini, 2020; Zheng et al., 2018).

Core Ideas

Twelve inbred lines highly resistant to common rust (CR) were identified in a 3‐year study.

The highly resistant inbred lines were genetically diverse.

The highly resistant inbred lines are potential donors of CR resistance alleles.

Sources of resistance to CR have been reported in temperate (Groth, Davis, Zeyen, & Mogen, 1983b; Kim & Brewbaker, 1976; Reid et al., 2017; Russell, Penny, Sprague, Guthrie, & Dicke, 1971) and in tropical maize. In tropical germplasm, inbred lines CML239–CML246 from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center were reported to be resistant (CIMMYT, 2005). However, there is limited published information on sources of resistance to CR in adapted maize lines for ESA. An earlier report indicated presence of resistance to CR among open‐pollinated varieties and an inbred line from Africa (Wilkinson & Hooker, 1968). In a recent study (Vivek et al., 2010), the response of hybrids formed from a limited number of lines adapted to the mid‐altitude ecology and evaluated under natural disease pressure was reported, with some lines exhibiting negative general combining ability effects for CR resistance. Zheng et al. (2018), evaluated an association mapping panel of 292 lines including some lines adapted to the mid‐altitudes under natural CR disease pressure and artificial inoculation in Kenya and Mexico respectively, and reported variable response to CR among some lines developed in Zimbabwe and Ethiopia. Rossi et al. (2020) evaluated some tropical lines from CIMMYT and reported six lines with low disease severity index for CR. The findings from these few studies indicate presence of native genetic resistance to CR among tropical maize germplasm sources. However, further research to identify new sources of resistance to CR in germplasm adapted to ESA is needed. The objectives of this study were to (i) evaluate the response of elite tropical adapted maize inbred lines to Puccinia sorghi and identify resistant lines (ii) examine associations between CR disease parameters and agronomic traits, and (iii) assess the genetic diversity of the inbred lines using high density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) DArTseq markers.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Genetic materials

A set of 50 inbred lines developed by CIMMYT maize breeding programs in Kenya (46 lines), Zimbabwe and Colombia (two each) were used for this study (Table 1). The lines were developed through pedigree breeding from bi‐parental crosses except five lines (42 to 46) that were derived using the doubled haploid (DH) method. Selection of lines for use in populations for inbred line development was based on good agronomic traits, resistance to foliar diseases (NCLB and GLS), maize streak virus, and tolerance to some abiotic stresses (drought, low N, and acid soils). Some of these lines used in this study have been used to develop hybrids of FAO maturity classification series 500–600 that have been evaluated widely in ESA (Magorokosho, Vivek, MacRobert, & Tarekegne, 2010; Makumbi, 2011). Forty eight out of the 50 inbred lines were of mid‐altitude ESA adaptation, and intermediate to late in maturity (819–966 growing degree days, GDD). The GDDs were calculated by setting maximum daily temperature at 30 °C and minimum daily temperature at 10 °C (Cross & Zuber, 1972). Weather information (daily temperature, relative humidity) was obtained from the weather station near nursery fields at Kiboko Research Station in Kenya. Seed production of the lines was done at Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) Kiboko Research Station in Kenya in 2016 and 2017. Genetic purity of the lines was verified using SNP markers as described by Semagn et al. (2012a). The resistant inbred line check was CML444, while the susceptible check was CKL141373. These two inbred line checks were chosen based on previous assessment under severe natural CR infestation at a location used regularly for disease screening in Kenya (Vivek et al., 2010).

TABLE 1.

List of 50 inbred lines used for common rust (Puccinia sorghi Schwein) screening at Namulonge, Uganda, 2017–2019

| Line | Name | Pedigree | Background/Derivation and notes | Growing degree days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CKL05003 | [CML202/CML395‐6]‐B‐B‐2‐1‐B‐B:4 | MSV × drought tolerant (DT), tolerant to rust | 949 |

| 2 | CKL05006 | [CML205/[EV7992#/EV8449‐SR]C1F2‐334‐1(OSU8i)‐1‐1‐Sn]‐B‐B‐2‐6‐B‐B‐B:4 | MSV × DT | 819 |

| 3 | CKL05007 | [CML205/CML202]‐B‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B:4 | MSV tolerance | 931 |

| 4 | CKL05010 | [CML395‐2/CML202]‐B‐3‐3‐3‐B‐B:4 | MSV × DT | 890 |

| 5 | CKL05017 | [CML387/CML390]‐B‐1‐1‐4‐B‐B:4 | MSV tolerance | 884 |

| 6 | CKL05018 | [CML387/CML390]‐B‐1‐2‐1‐B:4 | MSV tolerance | 891 |

| 7 | CKL05019 | [CML390/CML197]‐B‐B‐5‐1‐B:4 | MSV tolerance | 903 |

| 8 | CKL05024 | [KILIMA(ST94)‐S5:115/[M37W/ZM607#BF37SR…]]‐B‐B‐3‐5‐B‐B:4 | MSV tolerance | 860 |

| 9 | CKL147 | (CKL05019/(KU1403 × 1368)‐7‐2‐1‐B:5)‐B‐2‐1‐1‐1‐3‐B‐B‐B‐B | CIMMYT × IITA | 919 |

| 10 | CKL14504 | ECAVL29‐2‐3‐3‐1‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Extracted from synthetic | 860 |

| 11 | CKL14505 | ECAVL29‐2‐3‐3‐3‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | Extracted from synthetic | 860 |

| 12 | CKL141015 | (CKL05017/CML536)‐B‐55‐1‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 896 |

| 13 | CKL141025 | (CKL05018/CML536)‐B‐37‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 884 |

| 14 | CKL141291 | (CKL05006/La Posta Seq C7‐F180‐3‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B)‐B‐11‐2‐1‐3‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 866 |

| 15 | CKL141292 | (CKL05006/La Posta Seq C7‐F180‐3‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B)‐B‐11‐2‐1‐4‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 866 |

| 16 | CKL141020 | (CKL05018/CML536)‐B‐37‐1‐1‐3‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 884 |

| 17 | CKL14500 | ([CML444/CML395//DTPWC8F31‐1‐1‐2‐2‐BB]‐4‐2‐2‐1‐1‐B:4/(9071xBabamgoyo)‐3‐1‐BBB)‐B‐1‐2‐3‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | CIMMYT DT × IITA | 949 |

| 18 | CKL14501 | ([CML444/CML395//DTPWC8F31‐1‐1‐2‐2‐BB]‐4‐2‐2‐1‐1‐B:4/(9071xBabamgoyo)‐3‐1‐BBB)‐B‐1‐2‐3‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | CIMMYT DT × IITA | 915 |

| 19 | CKL14502 | ([CML444/CML395//DTPWC8F31‐1‐1‐2‐2‐BB]‐4‐2‐2‐1‐1‐B:4/(9071xBabamgoyo)‐3‐1‐BBB)‐B‐1‐2‐3‐1‐3‐B‐B‐B‐B | CIMMYT DT × IITA | 921 |

| 20 | CKL1515 | (CKL05006/CML489)‐B‐13‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 884 |

| 21 | CKL1522 | (CKL05006/CML489)‐B‐13‐1‐5‐4‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 932 |

| 22 | CKL14207 | (CKL05017/INTA/INTB‐B‐41‐B‐14‐1‐B)‐B‐25‐3‐1‐8‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × herbicide tolerance | 872 |

| 23 | CKL141248 | (CKL05003/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐1‐B)‐B‐11‐2‐2‐1‐3‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × acid soil tolerance (AT) | 884 |

| 24 | CKL141340 | (CKL05007/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B)‐B‐4‐1‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 879 |

| 25 | CKL141304 | (CKL05007/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B)‐B‐4‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 897 |

| 26 | CKL141344 | (CKL05007/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐1‐B)‐B‐1‐2‐2‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 848 |

| 27 | CKL141364 | (CKL05024/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐2‐3‐1‐B)‐B‐6‐3‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 861 |

| 28 | CKL141373 | (CKL05024/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B)‐B‐20‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 879 |

| 29 | CKL141374 | (CKL05024/CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐2‐3‐4‐B)‐B‐9‐1‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × AT | 932 |

| 30 | CKL141388 | ECAVL21‐37‐1‐3‐2‐1‐4‐B‐B‐B‐B | Extracted from synthetic | 891 |

| 31 | CKL141392 | ECAVL21‐37‐3‐3‐1‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Extracted from synthetic | 954 |

| 32 | CKL141398 | ECAVL21‐71‐1‐2‐2‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | Extracted from synthetic | 872 |

| 33 | CKL141134 | (MAS[MSR/312]‐117‐2‐2‐1‐B:6/ZM523A‐16‐2‐1‐1‐BBB)‐B‐4‐1‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | MSV × DT | 819 |

| 34 | CKL15622 | (POP 10‐B‐B/[(CML395/CML444)‐B‐4‐1‐3‐1‐B/CML395//DTPWC8F31‐1‐1‐2‐2]‐5‐1‐2‐2‐BBB‐B)‐B‐8‐8‐1‐3‐4‐B‐B | IITA × CIMMYT DT | 837 |

| 35 | CKL15636 | (CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B/[CML444/CML395//DTPWC8F31‐4‐2‐1‐6]‐3‐1‐2‐1‐1‐B:5‐B)‐B‐2‐2‐1‐B‐1‐B‐B | AT × DT | 848 |

| 36 | CKL15643 | (CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B/La Posta Seq C7‐F78‐2‐1‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B)‐B‐2‐5‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B | AT × DT | 867 |

| 37 | CKL15644 | (CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B/La Posta Seq C7‐F78‐2‐1‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B)‐B‐2‐5‐2‐2‐1‐B‐B | AT × DT | 854 |

| 38 | CKL177000 | (CKL05003/PHG39/CKL05003)‐B‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × ex‐PVPA | 878 |

| 39 | CKL172721 | (CKL05003/LH132/CKL05003)‐B‐2‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × ex‐PVPA | 908 |

| 40 | CKL177008 | (CKL05006/CML269/TX130‐BBB‐4‐4‐B:5‐B/CKL05006)‐B‐3‐2‐4‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × temperate | 884 |

| 41 | CKL172735 | (CKL05010/CML269/Tx114‐B‐6‐B:5‐B/CKL05010)‐B‐1‐2‐1‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × temperate | 908 |

| 42 | CKL1557 | (CKL05003/CML444//CKL05003)DH3‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 966 |

| 43 | CKL15140 | (CKL05003/La Posta Seq C7‐F64‐2‐6‐2‐2‐B‐B‐B)DH110‐B‐B‐B–B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 937 |

| 44 | CKL15193 | (CKL05006/La Posta Seq C7‐F71‐1‐2‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B)DH11‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 849 |

| 45 | CKL15194 | (CKL05006/La Posta Seq C7‐F71‐1‐2‐1‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B)DH15‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 866 |

| 46 | CKL1537 | (CKL05018/La Posta Seq C7‐F78‐2‐1‐1‐1‐B‐B‐B)DH58‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B‐B | Mid‐altitude × DT | 872 |

| 47 | CIMCAL2 | CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐2‐B‐B‐B‐B | AT | 855 |

| 48 | CIMCAL4 | CIMCALI8843/S9243‐BB‐#‐B‐5‐1‐BB‐4‐1‐3‐1‐B‐B‐B‐B | AT | 842 |

| 49 | CML395 | CML395 | DT, MSV | 920 |

| 50 | CML444 | CML444 | DT, low N, MSV, tolerance to rust | 926 |

AT, acid soil tolerance; DT, drought tolerance; ex‐PVPA, expired Plant Variety Protection Act; MSV, maize streak virus.

2.2. Test location, experimental design, and field evaluation

The inbred lines were evaluated in field trials for three seasons between 2017–2019 at National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI), Namulonge, Uganda, under artificial inoculation with Puccinia sorghi. The soil type at Namulonge (0°36’ N, 32°36’ E; 1150 m asl) is sandy clay loam and is classified as Orthic Ferrasol. The mean annual rainfall at Namulonge is 1270 mm with a bimodal distribution (March–July and September–November). The experimental design was a 5 × 10 alpha‐lattice (Patterson & Williams, 1976) with two replications. The experimental unit was a two‐row plot, 5 m long, spaced 0.75 m apart and 0.25 m between plants in a row, resulting in a final plant population density of approximately 53,333 plants ha−1. Standard location specific recommended agronomic and cultural practices were followed. Weeding was carried out by hand and fertilizer applied at a rate of 77 kg N and 27 kg P ha−1 split over two applications at planting and for topdressing four weeks after planting, respectively. The trials were planted under rain‐fed conditions with supplemental irrigation provided as required for optimal disease development. Since the evaluation was carried during the main cropping season, conditions were conducive for disease development (Supplemental Table S1).

2.3. Puccinia sorghi inoculum preparation

Urediniospores of Puccinia sorghi were collected from infected maize leaves at NaCRRI, Namulonge, Uganda in 2016 and maintained on a known susceptible experimental hybrid CKH107887 grown in a screenhouse. Spores of P. sorghi were collected from infected leaves by brushing them into 100 ml of distilled water containing 0.2 ml of Tween 20 to make an aqueous suspension of P. sorghi (Reuveni et al., 1994). Spore concentration in the suspension was estimated to be 5 × 104 spore ml−1 using a hemocytometer. The plants were inoculated once at the 4–6 leaf stage. Inoculation was carried out following the method of Olukolu et al. (2016), whereby a knapsack sprayer was used to deliver the spore suspension by spraying the whorl and upper surface of fully expanded leaves of each plant to run‐off.

2.4. Disease assessment and agronomic data recording

Disease severity was visually assessed by observing the symptoms on 28–34 plants in a plot. Sporulation was checked on both the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces. Disease severity was rated on nine‐point scale based on the percent leaf area showing pustules of P. sorghi where 1 = 0% of leaf surface diseased (no rust pustules or a few pustules scattered on the leaf surface), 2 = 1% of leaf surface diseased; 3 = 2% of leaf surface diseased; 4 = 3–5% of leaf surface diseased; 5 = 6–10% of leaf surface diseased; 6 = 11–20% of leaf surface diseased; 7 = 21–40% of leaf surface diseased; 8 = 41–80% of leaf surface diseased; and 9 = 81–100% of leaf surface diseased (CIMMYT, unpublished internal protocols). Disease reaction was scored thrice during crop growth. The first disease score (Rust 1) was taken 21 days after inoculation when there were discernible differences between plots for the severity of disease symptoms. The second score (Rust 2) was taken 28 days after inoculation, while the third score (Rust 3) was taken 35 days after inoculation. The three disease severity scores were used to calculate the area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) as:

where i = time of rust severity rating, Ti is the number of days after inoculation, and Yi is the rust severity (Shaner & Finney, 1977).

Additional traits measured on plot basis were days to anthesis (AD, recorded as days from planting to when 50% of the plants started to shed pollen), plant height (PH, measured in centimeters as the distance from the base of the plant to the base of the first tassel branch), ear height (EH, measured in centimeters as the distance from the base of the plant to the point of attachment of the top ear on a plant), and plant aspect (PA, scored on a scale of 1 to 5 for overall plant appearance where 1 = attractive plant type (uniform height and ear placement, and free of foliar diseases) while 5 = undesirable plant type (variable height and ear placement, and affected by foliar diseases). Reaction to GLS disease was recorded on a scale of 1–9 (same as for CR) when the crop was at the dough stage. All ears in a two‐row plot were harvested, weighed, and representative samples of ears shelled to determine percent moisture using a Dickey‐John multi‐grain moisture tester (DICKEY‐John Corporation, IL, USA). Grain yield (Mg ha−1) was calculated from cob weight assuming a shelling percentage of 80% and grain yield adjusted to 12.5% moisture content.

2.5. Genotyping

Seedlings of the 50 inbred lines were raised in a screenhouse at National Crops Resources Research Institute, Namulonge, Uganda. Leaf tissue was harvested following the leaf sampling protocol from LGC Genomics (http://www.lgcgroup.com/our-science/genomics-solutions/#.WXpE7ITyu70) using the plant sample collection kit from LGC Genomics (Middlesex, UK). DNA was extracted using ZR Plant/Seed DNA MiniPrepTM according to manufacturer's protocol and later shipped to Integrated Genotyping Sequence Support (IGSS) at Biosciences eastern and central Africa International Livestock Research Institute (BecA ‐ ILRI) Hub, Kenya for genotyping. Of the 50 inbred lines, 48 yielded good quality DNA for analysis. Extra quality check was carried out on 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis with lambda DNA of 50 ng as a marker. DNA for each sample was diluted to a required concentration range of 50–100 ng μl−1 for the DArTseq genotyping platform. Filtered genotypic data (using a minor allele frequency of 0.1 and a minimum count of 80% of the sample size) from IGSS was verified using TASSEL v.5.2 software (Bradbury et al., 2007) to retain 44,975 SNP markers for further analysis.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Homogeneity of variance of the data was ascertained using Levene's test before the analysis of variance. Analyses of variance were performed using PROC MIXED of SAS (SAS Institute, 2011). Entries were considered fixed effects, whereas seasons were considered random effects. Each season‐year combination was considered an environment. In the across‐environment analysis of variance, genotype effects were tested for significance using the corresponding interaction with the environment as the error term, whereas the genotype × environment interaction was tested using the pooled error. To estimate variance components, all factors were considered random effects. Best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP; Piepho, Möhring, Melchinger, & Büchse, 2008) for all traits was computed using META‐R (Alvarado et al., 2020). Broad‐sense heritability for traits across environments was estimated as described by Hallauer, Carena, and Miranda Filho (2010). Cluster analysis following Ward's minimum variance (Ward, 1963) was used to group lines with similar response to artificial inoculation with P. sorghi using a combination of Rust 1, Rust 2, Rust 3, and AUDPC. The SAS procedures PROC CLUSTER and PROC TREE were used for cluster analysis and to generate the dendrograms, respectively.

To assess consistency of inbred line performance in different seasons, Kendall's (1962) coefficient of concordance (W statistic) was computed for P. sorghi severity based on ranks of line means across artificial inoculation conditions. Kendall's W statistic is calculated as:

in which S is a sum‐of‐squares statistic over the row sums of ranks, n is the number of lines, p the number of locations, and T is a correction factor for tied ranks. Spearman rank correlation coefficients among rust severity scores and GLS were computed using PROC CORR of SAS (SAS Institute, 2011). Genetic correlations among traits were computed using META‐R (Alvarado et al., 2020). Sequential path analysis (Mohammadi, Prasanna, & Singh, 2003; Samonte, Wilson, & McClung, 1998) was used to examine cause and effect relationships among CR disease parameters and agronomic traits. In sequential path analysis, traits were categorized into first, second, and third order or higher depending on their contribution to the total variation in CR severity (Mohammadi et al., 2003, Samonte et al., 1998). We used sequential path analysis to avoid potential problems due to multicollinearity. Stepwise regression analysis was carried out in SPSS version 20 (IBM, 2011). In this analysis, Rust 3 was regressed on all other traits to identify first order traits. The first order traits were then regressed on other traits not among the first order traits to identify second‐order traits. The second‐order traits were then regressed on other traits not among the second‐order traits to identify third‐order traits. A trait was in first, second, or third order if it contributed significantly to variation in CR severity at P ≤ .05. Ordering traits into different categories allows identification of traits of primary (first‐order) and secondary (second‐order) importance, and then others. First‐order traits can be considered for use as indirect selection criteria. The standardized coefficient (b value) in stepwise regression analysis is equivalent to the direct path coefficient.

2.7. Diversity analysis

Genetic distance was computed between pairs of maize lines using identity by state method in TASSEL version 5.2 (Bradbury et al., 2007). A dendrogram was generated from the identity by state matrix using the neighbor‐joining option in TASSEL version 5.2, and the resulting tree was visualised and edited using the interactive tree of life (iTOL) tool (Letunic & Bork, 2019). The model‐based clustering approach implemented in STRUCTURE software (Pritchard, Stephens, & Donnelly, 2000) was used to analyze population structure, following the procedure described by Semagn et al. (2012b) and Sserumaga et al. (2019). Delta K was computed for each value of K using software Structure Harvester (Evanno, Regnaut, & Goudet, 2005).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analysis of variance and heritability

Individual environment ANOVA revealed significant (P < .05) differences among entries for all three rust disease severity ratings and AUDPC except Rust 1 in 2018 (Supplemental Table S2). Heritability for the disease resistance parameters was high (0.72–0.92) in 2017–2019 except for Rust 1 in 2017 and 2018 when it was moderate (0.52) or low (0.22), respectively (Table 2). Combined ANOVA across three environments showed significant (P < .001) environment mean squares for two disease severity scores Rust 1 and 2, and significant (P < .001) line mean squares for the three rust scores and AUDPC (Table 3). The line × environment interaction was significant (P < .001) for only Rust 1. Heritability was moderate for Rust 1 (0.59) and high (0.83–0.93) for the other disease parameters (Table 4). The genotypic variance was larger than the environment (1.5 ×) and genotype × environment variance (13.6 ×) for Rust 2. Significant (P < .01) line mean squares for grain yield, AD, and GLS were recorded in 2017 and 2018 while significant (P < .01) line mean squares for PH and EH were recorded in 2019 (Supplemental Table S3). Combined ANOVA revealed significant (P < .01) environment and line mean squares for grain yield, AD, PH, EH, and GLS.

TABLE 2.

Summary statistics, variance components and heritability of common rust severity scores and area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) for 50 tropical maize inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation with P. sorghi for three seasons, 2017–2019

| Year | Parameter | Range | LSD0.05 | CV | Genotypic variance | Residual variance | Heritability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Rust 1 | 1.0‐2.9 | 0.9 | 31.5 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.52 |

| Rust 2 | 1.0‐5.5 | 1.3 | 25.9 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.72 | |

| Rust 3 | 2.0‐8.9 | 2.5 | 28.9 | 2.53 | 1.53 | 0.77 | |

| AUDPC a | 18.5‐79.4 | 16.7 | 21.9 | 132.23 | 67.18 | 0.80 | |

| 2018 | Rust 1 | 1.0‐2.5 | 0.9 | 35.1 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Rust 2 | 1.0‐6.6 | 1.3 | 26.5 | 1.02 | 0.43 | 0.83 | |

| Rust 3 | 1.2‐8.4 | 2.2 | 20.6 | 3.51 | 1.13 | 0.86 | |

| AUDPC | 11.3‐82.2 | 19.3 | 24.2 | 166.77 | 89.18 | 0.79 | |

| 2019 | Rust 1 | 1.0‐4.3 | 1.4 | 36.1 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.73 |

| Rust 2 | 1.3‐7.6 | 1.1 | 14.2 | 1.60 | 0.30 | 0.91 | |

| AUDPC | 10.4‐66.1 | 10.3 | 14.7 | 141.46 | 24.93 | 0.92 |

AUDPC, area under disease progress curve; Rust 1, 2 and 3 are common rust severity scores 21, 28 and 35 days after inoculation, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Mean squares from combined ANOVA of 50 inbred lines evaluated under artificial P. sorghi inoculation at Namulonge across three seasons (2017–2019)

| Source | df | Rust 1 | Rust 2 | AUDPC a | df | Rust 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment (E) | 2 | 10.86::: | 55.29::: | 617.95 | 1 | 36.43: |

| Block (E × Rep) | 57 | 0.53:: | 0.96::: | 176.37::: | 38 | 3.94::: |

| Line | 49 | 1.12::: | 4.55::: | 674.17::: | 49 | 9.39::: |

| Line × E | 98 | 0.55::: | 0.51 | 64.21 | 49 | 1.90 |

| Residual | 87 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 65.38 | 58 | 1.41 |

:, ::, ::: Significant at the .05, .01, and .001 probability levels, respectively.

AUDPC, area under disease progress curve; Rust 1, 2 and 3 are common rust severity scores 21, 28 and 35 days after inoculation, respectively.

TABLE 4.

BLUPs of common rust (Puccinia sorghi) disease severity and area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) of 50 tropical maize inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation across three seasons, 2017–2019

| Rust severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | AUDPC a | Classification |

| 1 | CKL05003 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 27.8 | MR b |

| 2 | CKL05006 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 6.1 | 37.9 | MS |

| 3 | CKL05007 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 25.0 | Highly resistant |

| 4 | CKL05010 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 19.6 | Highly resistant |

| 5 | CKL05017 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 18.4 | Highly resistant |

| 6 | CKL05018 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 26.2 | Resistant |

| 7 | CKL05019 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 7.6 | 57.6 | HS |

| 8 | CKL05024 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 38.2 | Susceptible |

| 9 | CKL147 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 32.6 | Resistant |

| 10 | CKL14504 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 31.9 | Resistant |

| 11 | CKL14505 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 37.0 | MR |

| 12 | CKL141015 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 22.0 | Resistant |

| 13 | CKL141025 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 37.6 | MR |

| 14 | CKL141291 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 28.8 | Highly resistant |

| 15 | CKL141292 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 5.4 | 32.9 | MR |

| 16 | CKL141020 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 24.5 | Highly resistant |

| 17 | CKL14500 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 58.3 | Susceptible |

| 18 | CKL14501 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 7.0 | 56.3 | Susceptible |

| 19 | CKL14502 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 40.3 | MR |

| 20 | CKL1515 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 27.4 | Resistant |

| 21 | CKL1522 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 18.5 | Highly resistant |

| 22 | CKL14207 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 22.9 | Highly resistant |

| 23 | CKL141248 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 25.9 | Highly resistant |

| 24 | CKL141340 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 46.7 | MS |

| 25 | CKL141304 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 5.2 | 41.8 | MR |

| 26 | CKL141344 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 32.6 | MR |

| 27 | CKL141364 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 50.5 | HS |

| 28 | CKL141373 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 76.9 | HS |

| 29 | CKL141374 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 49.1 | MS |

| 30 | CKL141388 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 5.6 | 41.5 | MS |

| 31 | CKL141392 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 38.1 | MR |

| 32 | CKL141398 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 23.5 | Highly resistant |

| 33 | CKL141134 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 8.4 | 64.5 | HS |

| 34 | CKL15622 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 25.0 | Highly resistant |

| 35 | CKL15636 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 36.6 | MR |

| 36 | CKL15643 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 33.8 | MR |

| 37 | CKL15644 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 34.4 | MR |

| 38 | CKL177000 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 39.5 | MR |

| 39 | CKL172721 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 7.4 | 45.6 | Susceptible |

| 40 | CKL177008 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 30.8 | MR |

| 41 | CKL172735 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 25.8 | Highly resistant |

| 42 | CKL1557 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 30.6 | MR |

| 43 | CKL15140 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 44.6 | MS |

| 44 | CKL15193 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 42.4 | MS |

| 45 | CKL15194 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 39.8 | MR |

| 46 | CKL1537 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 40.6 | MR |

| 47 | CIMCAL2 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 51.4 | MS |

| 48 | CIMCAL4 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 50.7 | Susceptible |

| 49 | CML395 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 25.5 | Highly resistant |

| 50 | CML444 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 30.7 | MR |

| Range | 1.0‐3.1 | 1.4‐6.6 | 1.5‐8.7 | 18.4‐76.9 | ||

| Mean (resistant) | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 23.7 | ||

| Mean (susceptible) | 2.2 | 4.2 | 7.3 | 53.2 | ||

| LSD | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 9.2 | ||

| Heritability | 0.59 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.93 | ||

| Genotypic variance | 0.16 | 0.95 | 2.63 | 143.15 | ||

| Environment (E) variance | 0.13 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 4.05 | ||

| Genotype × E variance | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.00 | ||

| Residual variance | 0.34 | 0.41 | 1.36 | 64.47 | ||

AUDPC, area under disease progress curve, Rust 1, 2 and 3 are common rust severity scores 21, 28 and 35 days after inoculation, respectively.

HS, highly susceptible; MR, moderately resistant; MS, moderately susceptible.

3.2. Performance and classification of lines

The disease pressure was sufficient to differentiate among entries for their response to inoculation with P. sorghi. Disease severity scores in 2017 ranged from 1.0 to 2.9, 1.0 to 5.5 and 2.0 to 8.9 for Rust 1, Rust 2, and Rust 3, respectively (Table 2). In 2018, Rust 1 had a smaller range (1.0–2.5) compared to 2017 but a larger range was recorded in 2019 (1.0–4.3). The second Rust score varied more among entries in 2019 compared to 2018. The AUDPC ranged from 18.5 to 79.4 and 11.3 to 82.2 in 2017 and 2018, respectively (Table 2; Figure 1). In 2019 when only two disease scores were taken (Rust 1 and Rust 2), the range of AUDPC was smaller compared to the other two seasons. Across environments, disease severity scores ranged from 1.0 to 3.1, 1.4 to 6.6 and 1.5 to 8.7 for Rust 1, Rust 2, and Rust 3, respectively (Table 4). Lines showing the lowest scores (< 2) for Rust 2 were CKL05010, CKL05017, CKL141015, CKL14207, CKL141398, CKL1522, CKL15622 and CML395. Lines CKL05010, CKL05017, and CKL1522 maintained a score of <2 for Rust 3. The AUDPC varied from 18.4 to 76.9. The top three inbred lines with a score of < 2 for Rust 3 (CKL05017, CKL1522 and CKL05010) recorded 40.1%, 36.2% and 39.7% lower AUDPC, respectively, compared to the resistant check CML444. These three top lines recorded 74.5%, 76.1% and 75.9% lower AUDPC, respectively, compared to the susceptible check CKL141373.

FIGURE 1.

Boxplot showing distribution of AUDPC of 50 inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation with P. sorghi for three years at Namulonge, Uganda

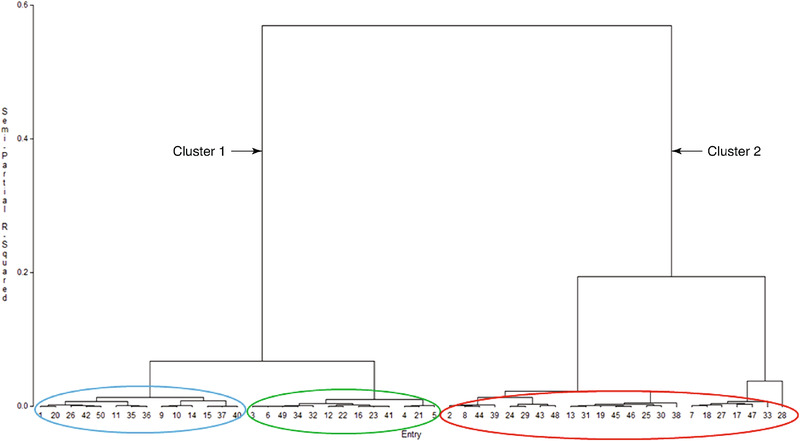

Based on Rust 3 severity scores across environments, lines were classified as either highly resistant (HR, score ≤3), resistant (score 3.1–3.9), moderately resistant (MR, score 4–5.5), moderately susceptible (MS, score 5.6–6.5), susceptible (score 6.6–7.5), or highly susceptible (HS, score ≥7.5). Eleven new elite inbred lines and CML395, a widely used line in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) were classified as highly resistant, five lines were classified as resistant, while 17 lines were classified as MR (Table 4). Inbred line CML444 that was included in the study as a resistant check was classified as MR. Based on AUPDC no line escaped infection or expressed immunity to CR. Using a combination of the three rust scores and AUDPC, the lines clustered into two clusters according to their response to artificial inoculation with P. sorghi (Figure 2). The resistant/moderately resistant (blue ellipse) and highly resistant/resistant (green ellipse) lines formed one cluster while the moderately susceptible, susceptible, and highly susceptible made up the other cluster (red ellipse). The only exception were seven lines (13, 19, 25, 31, 38, 45 and 46) which were classified as MR based on Rust 3 but clustered with the susceptible group.

FIGURE 2.

Dendrogram of 50 inbred lines based on three rust scores (Rust 1, Rust 2, and Rust 3) and AUDPC under artificial inoculation with P. sorghi for three seasons using Ward's minimum variance method. Blue, green and red ellipses represent lines classified as moderately resistant/resistant, resistant/highly resistant, and moderately susceptible/susceptible/highly susceptible, respectively

3.3. Consistency of line performance and relationships among rust severity scores and agronomic traits

The consistency of ranking of the inbred lines for their response to CR was assessed using Kendall's coefficient of concordance. The coefficient of concordance (W) was moderate for Rust 1 and Rust 3 and high for Rust 2 and AUDPC and was significant (P < .0001 or P = .001) for all traits (Supplemental Table S4). There were highly significant correlations between the three CR severity parameters, and between CR severity and AUDPC across seasons (Table 5). The AUDPC had a significant correlation with Rust 2 score (r = 0.984, P < .0001). Gray leaf spot severity was negatively and significantly correlated with all three CR severity parameters and AUDPC. The genetic correlation between CR disease resistance parameters ranged from 0.387 to 0.990 (Table 5). All the three CR disease resistance parameters had a positive and significant genetic correlation with AUDPC (r = 0.965–0.987, P < .0001). The genetic correlation between the CR disease resistance parameters and GLS and grain yield was negative and significant. Rust 3 showed a negative significant phenotypic correlation with grain yield.

TABLE 5.

Phenotypic (above diagonal) and genetic (below diagonal) correlation coefficients between BLUPs for common rust (Puccinia sorghi) disease rating and AUDPC across three seasons under artificial inoculation and gray leaf spot (GLS) severity and grain yield

| Rust 1 | Rust 2 | Rust 3 | AUDPC | GLS | Grain yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rust 1 | – | 0.876::: | 0.770::: | 0.893::: | −0.535::: | −0.194 ns |

| Rust 2 | 0.987::: | – | 0.870::: | 0.984::: | −0.591::: | −0.262 ns |

| Rust 3 | 0.387::: | 0.759::: | – | 0.922::: | −0.510::: | −0.293: |

| AUDPC | 0.987::: | 0.985::: | 0.965::: | – | −0.592::: | −0.256 ns |

| GLS | −0.845::: | −0.678::: | −0.310: | −0.626::: | – | −0.113 ns |

| Grain yield | −0.318: | −0.372:: | −0.516::: | −0.375:: | −0.099 ns |

:, ::, :::Significant at the .05, .01, and .001 probability levels, respectively.

AUDPC, area under disease progress curve; Rust 1, 2 and 3 are common rust severity scores 21, 28 and 35 days after inoculation, respectively.

ns, not significant.

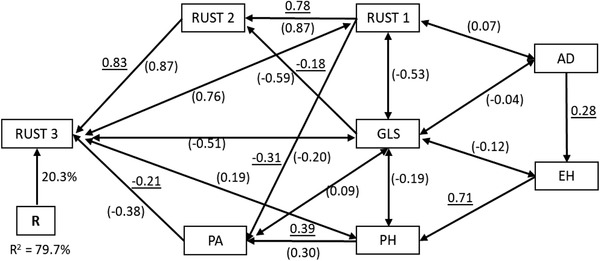

Spearman rank correlation coefficients for CR disease resistance parameters and AUDPC between seasons were significant (P < .0001) and ranged from 0.745–0.886 (Supplemental Table S5). Six of the 12 lines classified as HR using combined data (lines 3, 4, 5, 16, 21, and 32) were consistently ranked in the HR category in each of the three seasons (Supplemental Table S2). Lines 22, 23, 34, 41 and 49 which were also classified as HR were consistent as HR in two of the three seasons. Path analysis using stepwise regression identified Rust 2 and PA as the first‐order traits, which accounted for 79% of the variability in Rust 3 scores under artificial inoculation across three seasons (Figure 3). Of the two traits, Rust 2 had the largest and positive path coefficient (0.83). Rust 1, GLS, and PH were the second‐order traits that contributed to variation in Rust 3 scores, with Rust 1 and GLS contributing indirectly via Rust 2, while PH acted through PA. Rust 1 had the largest indirect effect (0.78) followed by plant height (0.39). Ear height (indirect effect 0.71) and AD (indirect effect 0.28) were the third‐ and fourth‐order traits that contributed to variation in Rust 3 scores through PH and EH, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Path analysis model diagram showing causal relationships among CR disease severity parameters, agronomic traits and GLS. The underlined values are direct path coefficients while values in parenthesis are correlation coefficients. Single‐arrowhead line represents a path coefficient while double‐arrowhead line is a correlation coefficient. AD, days to anthesis; EH, ear height; GLS, gray leaf spot; PA, plant aspect; PH, plant height; R, residual effects; Rust 1, 2, and 3 are CR disease severity scores at 21, 28, and 35 days after inoculation, respectively

3.4. Diversity of lines

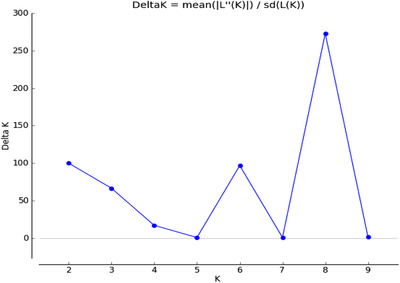

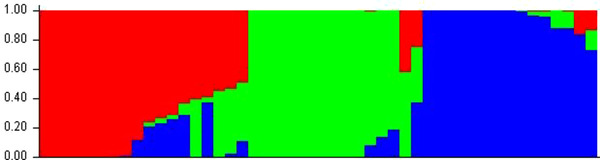

The neighbor‐joining (NJ) tree generated from identity by state matrix was used to understand the genetic diversity among this set maize lines. The dendrogram showed that the 48 lines were grouped into three major groups (Figure 4). The three groups consisted of 18 (37.5%), 14 (29.2%) and 16 (33.3%) inbred lines, respectively. Groups 1, 2 and 3 consisted of three, two and four subgroups, respectively. The three clusters did not show a clear pattern related to pedigree or breeding history. For example, the lines derived from CKL05006 (line 2; group 2) were in both groups 1 (six lines) and 2 (one line). Group 2 had five out of seven lines derived from the drought tolerant La Posta Sequía C7 background. Lines with temperate germplasm were in both groups 2 (three lines) and 3 (one line). Group 3 had four out of five lines with background of germplasm from IITA while the fifth line was in group 2. The lines classified as highly resistant to CR were spread across the three groups with four, three and five lines in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Results from STRUCTURE suggested the presence of either 2, 3, 4, 6 or 8 subgroups among the 48 lines (Figure 5). The ad hoc statistic ΔK sharply increased between K = 6 and K = 8, and less between K = 2 and K = 4. When the results from different K values were compared with pedigree and breeding history, the groups obtained at K = 3 appear to be the best possible number of populations (Figure 6). With K = 3, there was close agreement with the three groups based on NJ clustering. The membership of the lines in the 3 subgroups based on STRUCTURE was 37.5% (group 1) and 31.3% (groups 2 and 3).

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree for 50 maize inbred lines based on genetic distance calculated from identity by state matrix using 44,975 DArTseq SNP markers. The clusters have been colored to match the groups from STRUCTURE. The highly resistant inbred lines are shown in bold text

FIGURE 5.

Plot of changes in ΔK value with the number of subpopulations

FIGURE 6.

Population structure of the 50 inbred lines at ∆K = 3 based on 44,975 DArTseq SNP markers. Each sub‐population is represented by a different color (1 = red, 2 = green, 3 = blue)

4. DISCUSSION

Developing adapted maize germplasm with resistance to CR (Puccinia sorghi) for the target agro‐ecologies in SSA is an important breeding objective. Common rust has been projected to expand within the region in response to climate change (Ramirez‐Cabral et al., 2017). This study assessed response of diverse maize inbred lines to CR under artificial inoculation for three seasons. Results revealed significant differences among lines for CR, suggesting the presence of sufficient genetic variation that can be utilized in breeding for resistance to CR (Gingera et al., 1994; Kim & Brewbaker, 1977; Zheng et al., 2018). There was seasonal variation in CR severity which may be attributed to differences in temperature and relative humidity during field experimentation across the three seasons. Similar results have been reported for CR and southern leaf rust (Bailey, Wolfgang, Frederiksen, Bockholt, & Smith, 1987; Zheng et al., 2018). However, the AUDPC was consistent across seasons.

The line × environment interaction was not significant for Rust 2 and 3. This result is similar to that reported for lines and single cross hybrids evaluated for resistance to southern rust (Bailey et al., 1987) and for segregating populations evaluated for CR (Gingera et al., 1994). Limited line × environment interaction could be attributed to a longer first pustule appearance after inoculation (Gingera & Davis, 1995). The possible cause of nonsignificant line × environment interaction could not be established using the data collected in this study. The lack of a significant line × environment interaction suggested consistent response of the lines across the seasons for these two scores. The consistency of response of the lines to CR was supported by the significant rank correlation coefficients for the rust scores and AUDPC across seasons. Furthermore, there was consistent performance of lines as revealed by the significant coefficient of concordance. The consistency of performance suggests little or no variation between the rust inoculum across the three seasons and uniformity in inoculation procedures. The lines that were consistently classified as HR in each of the three seasons probably have stable resistance to CR. Identification of stable sources of resistance offers good prospects for control of CR through host‐plant resistance. The AUDPC did not show a significant line × environment interaction mean square, a result similar to that reported by Bailey et al. (1987). The heritability estimates were high for the disease resistance parameters every season and across seasons except for Rust 1, which could indicate consistency of disease pressure in the different seasons. The high heritability estimates for these two parameters suggests that genetic gain from selection for resistance to CR is likely to be high (Falconer & Mackay, 1996).

The inbred lines exhibited good variation in response to inoculation with P. sorghi. We identified 12 lines that were highly resistance to CR, and whose response to CR was better than that of the widely used inbred line CML444 which was included as a resistant check. Inbred lines CKL05010, CKL05017, CKL1522 and CKL141398 showed the best response to CR and could be used as donors for CR resistance. The identification of highly resistant lines was based on multiple disease severity ratings and AUDPC, which increases reliability and allows better control of selection decisions for disease resistance (Brown et al., 2001; Carson, 2006). The use of multiple disease ratings to identify disease resistance is useful in screening germplasm (Menkir & Ayodele, 2005; Zheng et al., 2018). Nine of the 12 inbred lines classified as highly resistant are newer inbred lines developed between 2014 and 2017 by combining elite lines from different CIMMYT maize breeding hubs in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Mexico and Colombia, and from IITA. These lines may potentially provide new alleles for resistance to P. sorghi and other adaptive traits that can be exploited to develop the new lines with multiple stress tolerance and higher yield potential.

Use of exotic germplasm is important for enriching the gene pool of different breeding programs to enhance genetic gains (Cupertino‐Rodrigues, Dhliwayo, Trachsel, Guo, & San Vicente, 2020; Menkir et al., 2006). Inbred line CKL177000 (line 38) derived from a backcross population between CKL05003 (MR) and an expired Plant Variety Protection Act line PHG39 (PI 600981) known to be susceptible to southern leaf rust expressed moderate resistance to CR. PHG39 has been reported to combine well with some tropical lines and expressed positive general combining ability for grain yield (Cupertino‐Rodrigues et al., 2020). Most of the highly resistant lines identified in this study are resistant/tolerant to NCLB, GLS, and maize streak virus (CIMMYT, unpublished data, 2015) which makes them good candidates for use in biparental populations for line development. In SSA, multiple disease resistance in parental inbred lines is important as there are several foliar and viral diseases some of which occur in combination that must be addressed through breeding (Fininsa & Yuen, 2001; Okori, Adipala, & Kyetere, 1999; Pratt et al., 2003; Vivek et al., 2010).

Resistance to CR is governed by a set of >25 dominant race‐specific Rp genes identified in diverse germplasm (Chavan, Gray, & Smith, 2015; Delaney, Webb, & Hulbert, 1998; Groth, Pataky, & Gingera, 1992; Hulbert, 1997; Webb et al., 2002). Limited information is available on which clusters of the Rp genes are present in tropical maize germplasm outside of the report by Wilkinson and Hooker (1968). Although host genetic background and the environmental conditions may significantly affect the performance of resistance genes, an investigation to determine the clusters of genes present in tropical germplasm highly resistant, resistant or MR to CR should be considered. A few studies have reported QTLs for rust resistance in tropical maize (Danson, Lagat, Kimani, & Kuria, 2008; Rossi et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2018). Some of the highly resistant lines identified in this study could be good candidates to develop populations for fine mapping some of the large effect QTLs for resistance to CR (Danson et al., 2008; Rossi et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2018) and potentially for development of breeder‐ready markers for selection in large breeding populations.

A genetic correlation between two traits may be due to pleiotropy and linkage disequilibrium while a phenotypic correlation is an additive combination of both genetic and environmental correlations. Both phenotypic and genetic correlations among CR scores were positive and strong. Based on this result and high heritability estimates for Rust 2, disease severity recorded 28 days after inoculation can reliably predict CR severity in later phenological stages. The strong positive genetic correlation between the CR resistance parameters suggests that these parameters are controlled by the same set of genes. Strong phenotypic correlations between disease severity ratings taken at multiple intervals have also been reported by Gingera et al. (1994) for CR and by Bailey et al. (1987) for southern rust. The correlation between the CR scores and AUDPC was strong, which suggested that AUDPC is a good measure of resistance. AUDPC does not vary with rate of disease development and should be routinely used for disease resistance screening.

In this study, we recorded a strong negative genetic correlation between CR scores 1 and 2 with GLS, which suggested that greater resistance to CR was associated with reduced resistance to GLS. This underscores the importance of testing lines across multiple biotic stresses and use of a multivariate selection index to select lines with resistance to both CR and GLS. This result is contrary to findings by Olukolu et al. (2016) who reported positive and small genetic correlation between CR and GLS. The difference in results between two studies could be attributed to different germplasm used. Path coefficient analysis was used to understand the important interrelationships among CR resistance parameters and agronomic traits. Path coefficient analysis indicated that Rust 2 had the largest direct path coefficient (0.83) with Rust 3. This suggests that to evaluate resistance to CR in different genotypes under artificial inoculation, disease rating taken 28 days after inoculation is a good indicator of scores 35 days after inoculation. A strong and significant genetic correlation between Rust 2 and Rust 3 (r = 0.759, P < .0001) further supports this conclusion. Taking CR disease score once 35 days after inoculation can save time and labor. However, disease resistance breeding programs in localities where labor is not expensive, should use AUDPC as the best measure of disease resistance.

Genetic diversity was assessed using identity by state and STRUCTURE in this set of lines. Clustering revealed genetic diversity among the inbred lines as showed by the three distinct clusters generated. This can be attributed to the diverse nature of the bi‐parental populations used to develop the lines which included tropical, subtropical, and temperate sources. Several studies with tropical maize inbred lines have reported diversity which was attributed to the large make‐up of the source germplasm used to develop the lines (Semagn et al., 2012b; Sserumaga et al., 2019; Warburton et al., 2002, 2008; Wu et al., 2016). Furthermore, the variation can be attributed to breeding system, selection, and differences in geographical origin of the source populations. It is worth noting that the new lines with resistance to CR were spread across the three clusters. This suggested diversity among these lines can be exploited to develop new lines through recycling. Since these lines already possess resistance to multiple diseases (foliar and virus diseases), they are potentially good candidates for recycling. For example, highly resistant line 21 (CKL1522, group 2, heterotic group B) could be used as a source of alleles to improve CR resistance in MR line 35 (CKL15636) and MS line 24 (CKL141340) in group 1, and MR line 19 (CKL14502, group 3) that have alleles from several other breeding programs. Similarly, highly resistant line 5 (CKL05017, group 3, heterotic group A) could be used to improve CR resistance in line 9 (resistant, group 2), which is a product of CIMMYT × IITA germplasm. Such bi‐parental crosses between genetically divergent lines will potentially result into combinations of several favorable alleles at different loci leading to new mid‐altitude adapted inbred lines with higher yield potential and multiple disease resistance.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study identified 12 inbred lines highly resistant to CR based on multiple disease severity ratings and AUDPC under artificial inoculation with Puccinia sorghi for three seasons. Eight of the 12 highly resistant lines were developed between 2014 and 2017 from different germplasm sources and contain many beneficial alleles for other traits. Assessment of CR resistance in a breeding program should be done using AUDPC which is not affected by environmental conditions. The diversity present among the lines can be exploited by recycling some of the highly resistant genetically distant lines with good genetic potential for important traits to develop new high yielding and multiple disease resistant inbred lines for hybrid development and deployment. The resistant lines could be used develop mapping populations to fine map QTLs for CR resistance. Furthermore, these highly resistant lines can be used to widen genetic diversity in other tropical maize breeding programs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS STATEMENT

JPS planned and performed field experiments and genotyping, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript; DM developed genetic materials, planned field experiments, analyzed data, drafted and reviewed the manuscript; SOA, EKM, and SGN developed genetic materials and reviewed the manuscript; BMJ and AYB planned experiments and reviewed the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplemental Table S1. Minimum and maximum temperature and relative humidity for three cropping seasons during which 50 maize inbred lines were evaluated for response to common rust under artificial inoculation with at Namulonge, Uganda, 2017‐2019.

Supplemental Table S2. BLUPs of common rust (Puccinia sorghi) disease severity and area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) of 50 tropical maize inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation for three seasons, 2017‐2019.

Supplemental Table S3. Summary ANOVA for agronomic traits of 50 inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation with P. sorghi at Namulonge, Uganda, 2017‐2019.

Supplemental Table S4. Kendall's coefficient of concordance (W) for 50 inbred lines evaluated under artificial inoculation with common rust (Puccinia sorghi) for three seasons at Namulonge, Uganda, 2017‐2019.

Supplemental Table S5. Spearman rank correlation coefficients between BLUPs for common rust (Puccinia sorghi) disease ratings and AUDPC across three seasons under artificial inoculation and gray leaf spot (GLS) severity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) through the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA, OPPGD1390) and Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA, OPP1134248). Additional financial support was obtained from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and CGIAR Research Program (CRP) MAIZE. The CRP MAIZE receives W1 & W2 support from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, France, India, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the World Bank. We thank technical staff at National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI), Namulonge, Uganda for assistance with trial management and data collection. We gratefully thank Dr. George Mahuku who provided insightful comments and suggestions on this paper.

Sserumaga JP, Makumbi D, Assanga SO, et al. Identification and diversity of tropical maize inbred lines with resistance to common rust (Puccinia sorghi Schwein). Crop Science. 2020;60:2971–2989. 10.1002/csc2.20345

Assigned to Associate Editor Irwin Goldman.

REFERENCES

- Abedon, B. G. , & Tracy, W. F. (1998). Direct and indirect effects of full‐sib recurrent selection for resistance to common Rust (Puccinia sorghi Schw.) in three sweet corn populations. Crop Science, 38, 56–61. 10.2135/cropsci1998.0011183X003800010010x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, G. , Rodríguez, F. M. , Pacheco, A. , Burgueño, J. , Crossa, J. , Vargas, M. , … Lopez‐Cruz, M. A. (2020). META‐R: A software to analyze data from multi‐environment plant breeding trials. Crop Journal. 10.1016/j.cj.2020.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. A. , Tyler, B. M. , & Pryor, A. (1992). Genome complexity of the maize rust fungus, Puccinia sorghi . Experimental Mycology, 16, 302–307. 10.1016/0147-5975(92)90006-D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asea, G. , Bigirwa, G. , Adipala, E. , Powera, S. A. , Pratt, R. C. , & Lipps, P. E. (2002). Effect of Cercospora zeae‐maydis infested maize residue on the progress and spread of grey leaf spot of maize in central Uganda. Annals of Applied Biology, 140, 177–185. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2002.tb00171.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, B. A. , Wolfgang, S. , Frederiksen, R. A. , Bockholt, A. J. , & Smith, J. D. (1987). Identification of slow‐rusting resistance to Puccinia polysora in maize inbreds and single crosses. Plant Disease, 71, 518–521. 10.1094/PD-71-0518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bekeko, Z. (2019). Distribution and importance of common rust (Puccinia sorghi Schw.) of maize in Hararghe highlands, Eastern Ethiopia. East African Journal of Science, 13, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bigirwa, G. , Pratt, R. C. , Adipala, E. , & Lipps, P. E. (2001). Assessment of gray leaf spot and stemborer incidence and severity on maize in Uganda. African Crop Science Conference Proceedings, 4, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, P. , Zhang, Z. , Kroon, D. , Casstevens, T. , Ramdoss, Y. , & Buckler, E. (2007). TASSEL: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics, 23, 2633–2635. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. F. , Juvik, J. A. , & Pataky, J. K. (2001). Quantitative trait loci in sweet corn associated with partial resistance to Stewart's wilt, northern corn leaf blight, and common rust. Phytopathology, 91, 293–300. 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.3.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABI . (2019). Puccinia sorghi (common rust of maize). Invasive species compedium. Retrieved from https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/45872 (Accessed 9 June 2020).

- Carson, M. L. (2006). Response of a maize synthetic to selection for components of partial resistance to Exserohilum turcicum . Plant Disease, 90, 910–914. 10.1094/PD-90-0910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, S. , Gray, J. , & Smith, S. M. (2015). Diversity and evolution of Rp1 rust resistance genes in four maize lines. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 128, 985–998. 10.1007/s00122-015-2484-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIMMYT (2005). Maize inbred lines released by CIMMYT. El Batan, Texcoco, Mexico: CIMMYT. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, H. Z. , & Zuber, M. S. (1972). Prediction of flowering dates in maize based on different methods of estimating thermal units. Agronomy Journal, 64, 351–355. 10.2134/agronj1972.00021962006400030029x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cupertino‐Rodrigues, M. , Dhliwayo, T. , Trachsel, S. , Guo, R. , & San Vicente, F. (2020). Evaluation of U.S. inbred lines with expired plant variety protection for mid‐altitude tropical maize breeding. Euphytica, 216, 44 10.1007/s10681-020-02584-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danson, J. , Lagat, M. , Kimani, M. , & Kuria, A. (2008). Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to grey leaf spot and common rust diseases of maize. African Journal Biotechnology, 7, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar]

- Darino, M. A. , Rochi, L. , Lia, V. V. , Kreff, E. D. , Pergolesi, M. F. , Ingala, L. R. , … Sacco, F. (2016). Virulence characterization and identification of maize lines resistant to Puccinia sorghi Schwein present in the Argentine Corn Belt region. Plant Disease, 100, 770–776. 10.1094/PDIS-06-15-0639-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, D. E. , Webb, C. A. , & Hulbert, S. H. (1998). A novel rust resistance gene in maize showing overdominance. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 11, 242–245. 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.3.242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey, U. , Harlapur, S. I. , Dhutraj, D. N. , Suryawanshi, A. P. , Badgujar, S. L. , Jagtap, G. P. , & Kuldhar, D. P. (2012). Spatiotemporal yield loss assessment in corn due to common rust caused by Puccinia sorghi Schw. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7, 5265–5269. 10.5897/AJAR12.1103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dey, U. , Harlapur, S. I. , Dhutraj, D. N. , Suryawanshi, A. P. , Jagtap, J. P. , Apet, K. T. , … Kuldhar, D. P. (2013). Effect of fungicides, botanicals, bioagents and Indigenous Technology Knowledge (ITK's) on germination of urediniospores of Puccinia sorghi in vitro. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 8, 4960–4971. 10.5897/AJAR2013.7770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno, G. , Regnaut, S. , & Goudet, J. (2005). Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Molecular Ecology, 14, 2611–2620. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, D. , & Mackay, T. (1996). Introduction to quantitative genetics (4th edn). Essex, UK: Longman Group Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT . (2018). FAOSTAT database. FAO, Rome: Retrieved from http://faostat.fao.org (Accessed 1 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Fininsa, C. , & Yuen, J. (2001). Association of maize rust and leaf blight epidemics with cropping systems in Hararghe highlands, eastern Ethiopia. Crop Protection, 20, 669–678. 10.1016/S0261-2194(01)00033-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gingera, G. R. , Davis, D. W. , & Groth, J. V. (1994). Pedigree selection for improved partial resistance to common leaf rust in sweet corn. Crop Science, 34, 615–620. 10.2135/cropsci1994.0011183X003400030002x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gingera, G. R. , & Davis, D. W. (1995). Identification and inheritance of delayed first pustule appearance to common leaf rust in sweet corn. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science, 120, 667–672. 10.21273/JASHS.120.4.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goergen, G. , Kumar, P. L. , Sankung, S. B. , Togola, A. , & Tamò, M. (2016). First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS One, 11, e0165632 10.1371/journal.pone.0165632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J. V. , Zeyen, R. J. , Davis, D. W. , & Christ, B. J. (1983a). Yield and quality losses caused by common rust (Puccinia sorghi Schw.) in sweet corn (Zea mays) hybrids. Crop Protection, 2, 105–111. 10.1016/0261-2194(83)90030-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J. V. , Davis, D. W. , Zeyen, R. J. , & Mogen, B. D. (1983b). Ranking of partial resistance to common rust (Puccinia sorghi Schw.) in 30 sweet corn (Zea mays) hybrids. Crop Protection, 2, 219–223. 10.1016/0261-2194(83)90047-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J. V. , Pataky, J. K. , & Gingera, G. R. (1992). Virulence in eastern North American populations of Puccinia sorghi to Rp resistance genes in corn. Plant Disease, 76, 1140–1144. 10.1094/PD-76-1140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallauer, A. R. , Carena, M. , & Miranda Filho, J. B. (2010). Quantitative genetics in maize breeding (3rd ed). Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Headrick, J. M. , & Pataky, J. K. (1987). Expression of partial resistance to common rust in sweet corn hybrids at various host growth stages. Phytopathology, 77, 454–458. 10.1094/Phyto-77-454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, A. L. (1985). Corn and sorghum rusts. In Diseases, Distribution, Epidemiology, and Control (pp. 207–236). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert, S. H. (1997). Structure and evolution of the rp1 complex conferring rust resistance in maize. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 35, 293–310. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G. , & Hulbert, S. (1996). Construction of ‘compound’ rust resistance genes in maize. Euphytica, 87, 45–51. 10.1007/BF00022963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert, S. H. , Lyons, P. C. , & Bennetzen, J. L. (1991). Reactions of maize lines carrying Rp resistance genes to isolates of the common rust pathogen, Puccinia sorghi . Plant Disease, 75, 1130–1133. 10.1094/PD-75-1130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM (2011). SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kanampiu, F. , Makumbi, D. , Mageto, E. , Omanya, G. , Waruingi, S. , Musyoka, P. , & Ransom, J. (2018). Assessment of management options on Striga infestation and maize grain yield in Kenya. Weed Science, 66, 516–524. 10.1017/wsc.2018.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M. G. (1962). Rank correlation methods (3rd ed). London: Griffin. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, M. R. , Dudley, J. W. , & Rufener, G. K. (1999). QTL for resistance to common rust and smut in maize. Maydica, 44, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kfir, R. , Overholt, W. A. , Khan, Z. R. , & Polaszek, A. (2002). Biology and management of economically important lepidopteran cereal stem borers in Africa. Annual Review of Entomology, 47, 701–731. 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. K. , & Brewbaker, J. L. (1976). Effects of Puccinia sorghi rust on yield and several agronomic traits of maize in Hawaii. Crop Science, 16, 874–877. 10.2135/cropsci1976.0011183X001600060035x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. K. , & Brewbaker, J. L. (1977). Inheritance of general resistance in maize to Puccinia sorghi Schw. Crop Science, 77, 456–461. 10.2135/cropsci1977.0011183X001700030029x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyetere, D. T. , Ming, R. , McMullen, M. D. , Pratt, R. C. , Brewbaker, J. , & Musket, T. (1999). Genetic analysis of tolerance to maize streak virus in maize. Genome, 42, 20–26. 10.1139/g98-099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic, I. , & Bork, P. (2019). Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Research, 47, W256–W259. 10.1093/nar/gkz239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübberstedt, T. , Klein, D. , & Melchinger, A. E. (1998). Comparative quantitative trait loci mapping of partial resistance to Puccinia sorghi across four populations of European flint maize. Phytopathology, 88, 1324–1329. 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.12.1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magorokosho, C. , Vivek, B. , MacRobert, J. , & Tarekegne, A. (2010). Characterization of maize germplasm grown in eastern and southern Africa: Results of the 2009 regional trials coordinated by CIMMYT. Harare, Zimbabwe: : CIMMYT. [Google Scholar]

- Mahuku, G. , Lockhart, B. E. , Wanjala, B. , Jones, M. W. , Kimunye, J. N. , Stewart, L. R. , … Redinbaugh, M. G. (2015). Maize Lethal Necrosis (MLN), an emerging threat to maize‐based food security in sub‐Saharan Africa. Phytopathology, 105, 956–965. 10.1094/PHYTO-12-14-0367-FI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makumbi, D. (2011). Results of the 2010 regional trials coordinated by CIMMYT‐Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: CIMMYT. [Google Scholar]

- Marenya, P. P. , Erenstein, O. , Prasanna, B. , Makumbi, D. , Jumbo, M. , & Beyene, Y. (2018). Maize lethal necrosis disease: Evaluating agronomic and genetic control strategies for Ethiopia and Kenya. Agricultural Systems, 162, 220–228. 10.1016/j.agsy.2018.01.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. P. , & Shepherd, D. N. (2009). The epidemiology, economic impact and control of maize streak disease. Food Security, 1, 305–315. 10.1007/s12571-009-0023-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menkir, A. , & Ayodele, M. (2005). Genetic analysis of resistance to grey leaf spot of midaltitude maize inbred lines. Crop Science, 45, 163–170. 10.2135/cropsci2005.0803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menkir, A. , Olowolafe, M. O. , Ingelbrecht, I. , Fawole, I. , Badu‐Apraku, B. , & Vroh, B. I. (2006). Assessment of testcross performance and genetic diversity of yellow endosperm maize linesderived from adapted × exotic backcrosses. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 113, 90–99. 10.1007/s00122-006-0275-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S. A. , Prasanna, B. M. , & Singh, N. N. (2003). Sequential path model for determining interrelationships among grain yield and related characters in maize. Crop Science, 43, 1690–1697. 10.2135/cropsci2003.1690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mugo, S. , De Groote, H. , Songa, J. , Mulaa, M. , Odhiambo, B. , Taracha, C. Bergvinosn , … Gethi, M. (2004). Advances in developing insect resistanct maize varieties for Kenya within the insect resistant maize for Africa (IRMA) project. In: Friesen D. K. & Palmer A. F. E. editors, Integrated approaches to higher maize productivity in the new millennium (p. 31–37). Proceedings of the 7th Eastern and Southern Africa regional maize conference, Nairobi, Kenya. 5–11 February 2002. CIMMYT/KARI.

- Okori, P. , Adipala, E. , & Kyetere, D. T. (1999). Induced resistance to turcicum leaf blight in maize when doubly infected with maize streak virus disease. International Journal of Pest Management, 45, 111–116. 10.1080/096708799227897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olukolu, B. A. , Tracy, W. F. , Wisser, R. , De Vries, B. , & Balint‐Kurti, P. J. (2016). A genome‐wide association study for partial resistance to maize common rust. Phytopathology, 106, 745–751. 10.1094/PHYTO-11-15-0305-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pataky, J. K. (1987). Quantitative relationships between sweet corn yield and common rust, Puccinia sorghi . Phytopathology, 77, 1066–1071. 10.1094/Phyto-77-1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pataky, J. K. , & Eastburn, D. M. (1993). Comparing partial resistance to Puccinia sorghi and applications of fungicides for controlling common rust on sweet corn. Phytopathology, 83, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Pataky, J. K. , & Headrick, J. M. (1989). Management of common rust on sweet corn with resistance and fungicides. Journal of Productions Agriculture, 2, 362–369. 10.2134/jpa1989.0362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pataky, J. K. , & Tracy, W. F. (1999). Widespread occurrence of common rust, caused by Puccinia sorghi, on Rp‐resistant sweet corn in the midwestern United States. Plant Disease, 83, 1177 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.12.1177D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, H. D. , & Williams, E. R. (1976). A new class of resolvable incomplete block designs. Biometrika, 63, 83–92. 10.1093/biomet/63.1.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piepho, H. P. , Möhring, J. , Melchinger, A. E. , & Büchse, A. (2008). BLUP for phenotypic selection in plant breeding and variety testing. Euphytica, 161, 209–228. 10.1007/s10681-007-9449-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, B. , Suresh, L. M. , Mwatuni, F. , Beyene, Y. , Makumbi, D. , Gowda, M. , … Lassen, P. (2020). Maize lethal necrosis (MLN): Efforts toward containing the spread and impact of a devastating transboundary disease in sub‐Saharan Africa. Virus Research, 282, 197943 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, R. C. , & Gordon, K. (2006). Breeding for resistance to maize foliar pathogens. Plant Breeding Reviews, 27, 119–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, R. C. , Gordon, K. , Lipps, P. , Asea, G. , Bigirwa, G. , & Pixley, K. (2003). Use of IPM in the control of multiple diseases of maize. African Crop Science Journal, 11, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J. , Stephens, M. , & Donnelly, P. (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics, 155, 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, T. (1994). Maize and Puccinia sorghi: A system for the study of the genetic and molecular basis of host‐pathogen interactions New York: Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4612-2694-9_36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez‐Cabral, N. Y. Z. , Kumar, L. , & Shabani, F. (2017). Global risk levels for corn rusts (Puccinia sorghi and Puccinia polysora) under climate change projections. Journal of Phytopathology, 165, 563–574. 10.1111/jph.12593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randle, W. M. , Davis, D. W. , & Groth, J. V. (1984). Improvement and genetic control of partial resistance in sweet corn to corn leaf rust. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science, 109, 777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, L. M. , Zhu, X. , Wu, J. , Jindal, K. K. , Woldemariam, T. , & Voloaca, C. (2017). Common rust‐resistant corn inbred lines CO457, CO458, CO459, and CO460. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 97, 356–364. 10.1139/cjps-2016-0145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni, R. , Agapov, V. , & Reuveni, M. (1994). Foliar spray of phosphates induces growth increase and systemic resistance to Puccinia sorghi in maize. Plant Pathology, 43, 245–250. 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1994.tb02682.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs A.P., & Bushnell W.R. (eds). (1985). The cereal rusts, Volume II: Diseases, distribution, epidemiology and control. London and Orlando: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, E. A. , Ruiz, M. , Bonamico, N. C. , & Balzarini, M. G. (2020). Identifying inbred lines with resistance to endemic diseases in exotic maize germplasm. Crop Science. 10.1002/csc2.20275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, W. A. , Penny, L. H. , Sprague, G. F. , Guthrie, W. D. , & Dicke, F. F. (1971). Registration of maize parental lines. Crop Science, 11, 143 10.2135/cropsci1971.0011183X001100010083x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samonte, S. O. P. B. , Wilson, L. T. , & McClung, A. M. (1998). Path analyses of yield and yield‐related traits of fifteen diverse rice genotypes. Crop Science, 38, 1130–1136. 10.2135/cropsci1998.0011183X003800050004x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, M. V. , Nesci, A. V. , Montemarani, A. M. , Barros, G. G. , García, J. , & Etcheverry, M. G. (2017). Preliminary evaluation of biocontrol agents against maize pathogens Exserohilum turcicum and Puccinia sorghi in field assays. Agricultural Sciences, 0809, 1003–1013. 10.4236/as.2017.89073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . (2011). SAS/STAT 9.3 user's guide. Cary, NC:SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Semagn, K. , Beyene, Y. , Makumbi, D. , Mugo, S. , Prasanna, B. M. , Magorokosho, C. , & Atlin, G. (2012a). Quality control genotyping for assessment of genetic identity and purity in diverse tropical maize inbred lines. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 125, 1487–1501. 10.1007/s00122-012-1928-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semagn, K. , Magorokosho, C. , Vivek, B. S. , Makumbi, D. , Beyene, Y. , Mugo, S. , … Warburton, M. L. (2012b). Molecular characterization of diverse CIMMYT maize inbred lines from eastern and southern Africa using single nucleotide polymorphic markers. BMC Genomics, 13, 113 10.1186/1471-2164-13-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, D. A. , & Dillard, H. R. (2006). Yield loss in sweet corn caused by Puccinia sorghi: A meta‐analysis. Plant Disease, 90, 1413–1418. 10.1094/PD-90-1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner, G. , & Finney, R. E. (1977). The effect of nitrogen fertilizer on the expression of slow‐mildewing resistance in Knox wheat. Phytopathology, 67, 1051–1056. 10.1094/Phyto-67-1051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sserumaga, J. P. , Makumbi, D. , Warburton, M. L. , Opiyo, S. O. , Asea, G. , Muwonge, A. , & Kasozi, C. L. (2019). Genetic diversity among tropical provitamin A maize inbred lines and implications for a biofortification program. Cereal Research Communications, 47, 134–144. 10.1556/0806.46.2018.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivek, B. S. , Odongo, O. , Njuguna, J. , Imanywoha, J. , Bigirwa, G. , Diallo, A. , & Pixley, K. (2010). Diallel analysis of grain yield and resistance to seven diseases of 12 African maize (Zea mays L.) inbred lines. Euphytica, 172, 329–340. 10.1007/s10681-009-9993-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wangai, A. W. , Redinbaugh, M. G. , Kinyua, Z. M. , Miano, D. W. , Leley, P. K. , Kasina, M. , … Jeffers, D. (2012). First report of maize chlorotic mottle virus and maize lethal necrosis in Kenya. Plant Disease, 96, 1582 10.1094/PDIS-06-12-0576-PDN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, M. L. , Xianchun, X. , Crossa, J. , Franco, J. , Melchinger, A. E. , Frisch, M. , … Hosington, D. (2002). Genetic characterization of CIMMYT inbred maize lines and open pollinated populations using large scale fingerprinting methods. Crop Science, 42, 1832–1840. 10.2135/cropsci2002.1832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, M. L. , Reif, J. C. , Frisch, M. , Bohn, M. , Bedoya, C. , Xia, X. C. , … Melchinger, A. E. (2008). Genetic diversity in CIMMYT nontemperate maize germplasm: Landraces, open pollinated varieties, and inbred lines. Crop Science, 48, 617–624. 10.2135/cropsci2007.02.0103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J. H. (1963). Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58, 236–244. 10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J. M. J. , Stromberg, E. L. , Nowell, D. C. , & Nutter Jr, F. W. (1999). Gray leaf spot: A disease of global importance in maize production. Plant Disease, 83, 884–895. 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.10.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, C. A. , Richter, T. E. , Collins, N. C. , Nicolas, M. , Trick, H. N. , Pryor, T. , & Hulbert, S. H. (2002). Genetic and molecular characterization of the maize rp3 rust resistance locus. Genetics, 162, 381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]