ABSTRACT

Surgery for adult obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) plays a key role in contemporary management paradigms, most frequently as either a second‐line treatment or in a facilitatory capacity. This committee, comprising two sleep surgeons and three sleep physicians, was established to give clarity to that role and expand upon its appropriate use in Australasia. This position statement has been reviewed and approved by the Australasian Sleep Association (ASA) Clinical Committee.

Keywords: airway, clinical sleep medicine, nasendoscopy, sleep apnoea, surgery

Abbreviations

- ABG

arterial blood gas

- AHI

apnoea‐hypopnoea index

- ASA

Australasian Sleep Association

- ASOHNS

Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- CT

computed tomography

- COX‐2 inhibitors

cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors

- DISE

drug‐induced sleep endoscopy

- EDS

excessive daytime sleepiness

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FOSQ

Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

- FTG

Friedman tongue position

- HGNS

hypoglossal nerve stimulation

- ISSS

International Surgical Sleep Society

- LASER

leave as is, because it is not an abbreviation

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MAS

mandibular advancement splint

- MBS

Medicare Benefits Schedule

- MVA

motor vehicle accident

- NZSOHNS

New Zealand Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery

- ODI

oxygen desaturation index

- OHS

obesity hypoventilation syndrome

- OPG

orthopantomogram

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnoea

- PACU

post‐anaesthesia care unit

- Pcrit

pharyngeal critical pressure

- Paco2

arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PE

pulmonary embolism

- PSG

polysomnography

- RAST

radioallergosorbent test

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- REM

rapid eye movement

- RFTA

radiofrequency tissue ablation

- QOL

quality of life

- Spo2

peripheral oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry

- SPT

skin prick testing

- UA

upper airway

- UAS

upper airway stimulation

- UPPP

uvulopalatopharyngoplasty.

INTRODUCTION

Surgery for adult obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) has an important role, particularly as a salvage treatment modality when patients are unable to tolerate or adhere to devices (such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mandibular advancement splint (MAS)), and as an adjunctive/facilitatory treatment to aid in device use (as with pre‐phase nasal surgery or operations to lower CPAP requirements). In children, surgery such as adenotonsillectomy is considered the first‐line therapy.

The role of surgery becomes even more important when one considers the significant burden of untreated disease. OSA has long been recognized as a ‘tip of the iceberg’ condition, with many cases undiagnosed, many diagnosed but remaining untreated, and many only partially treated due to compliance issues. Up to 50% of patients will abandon device therapy in the first week after prescription. This carries significant community impact: health and economic burden relate to short‐ and long‐term medical consequences, work and social injury and accident risk, and far‐reaching reduction in an individual's quality of life.

Results of a recently completed Australian multicentre NHMRC‐funded clinical trial 1 in multilevel airway surgery in adults with OSA, who could not comply with device use, have recently been published. Future research is planned to enable refinement of the identification and selection of appropriate patients and surgeries in order to reduce the burden of disease. Development of tailored approaches in order to offer salvage surgery or even earlier surgery to appropriate anatomical/phenotypic candidates is also required.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF THE ROLE OF SURGERY IN ADULT OSA

The ENT surgeon involved in adult OSA surgery has an obligation to promote benefit and mitigate risk based on the best available evidence. Indications for airway surgery may include:

Failed compliance with/intolerance of device therapy

Significant complications of device therapy

Patient favours surgery, declining all other options

Patient has particularly favourable anatomy for surgery

It should be noted that (iii) and (iv) are open to debate dependent upon expert opinion and patient preference.

More recently, modified uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and submucosal insertions of a radiofrequency‐in‐saline wand to reduce tongue volume have been tested at the highest level of evidence, demonstrating a key role for surgical intervention based on a range of primary and secondary outcomes in the trial. 1 Existing international literature supports a role for surgery across many domains including:

Function/ Quality of Life (QOL)

Cardiovascular risk

Mortality

Motor vehicle accident (MVA) risk

Polysomnographic parameters of disease

Cost‐effectiveness

These publications are at Level I (individual randomized controlled trial (RCT) and also systematic reviews/meta‐analyses, see Appendix S1 under ‘A’ (Supplementary Information)) and Level II (large individual cohort and observational or multicentre studies, see Appendix S1 under ‘B’ (Supplementary Information)), studies supported by the International Surgical Sleep Society as providing sufficient evidence of effect, at the time of publication (see Appendix S1 under ‘C’ (Supplementary Information)) and finally literature regarding the philosophy and judgement of sleep apnoea surgery (see Appendix S1 under ‘D’ (Supplementary Information)). Under ‘E’ is to what degree consensus statements are supported in this document.

It is also noted by the committee that adult OSA treatment can no longer have a ‘one‐size‐fits‐all approach’ and the future of personalized medicine in OSA will require an integrated approach by marrying anatomical, physiological and other information to formulate a tailored plan for the individual patient.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

Essential, preferred and optional components

Assessment is defined as the summation of clinical history, examination, formal polysomnography (PSG; for patients at risk of OSA as per MBS Guidelines) and completion of a range of predictive or treatment questionnaires.

There is no precise airway examination or assessment tool that can provide a perfect predictor of surgical outcome; it can be considered a skilled art form rather than an exact science.

In the assessment of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), other sleep disorders need consideration, such as narcolepsy, and medical and psychological comorbidities, such as depression, prior to committing to OSA surgery.

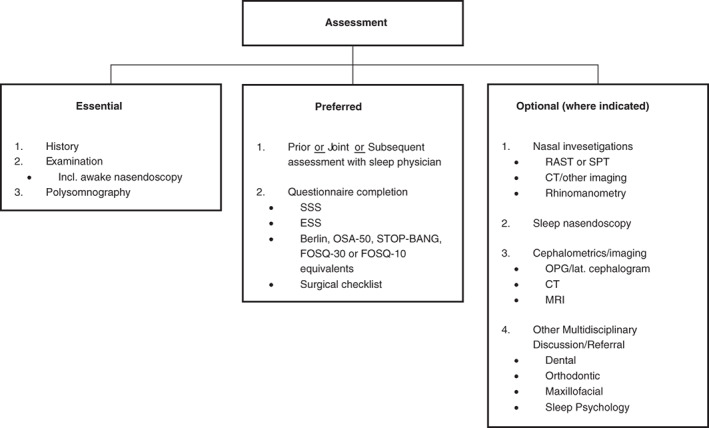

The essential, preferred and optional assessment components are explained in Figure 1 and Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Figure 1.

Clinical assessment and evaluation: essential, preferred and optional components. Also consider pre‐anaesthesia studies. CT, computed tomography; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FOSQ, Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OPG, orthopantomogram; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; RAST, radioallergosorbent test; SPT, skin prick testing; SSS, Snoring Severity Scale. STOP‐BANG sleep apnoea questionnaire: Snoring Tired Observed (choking/gasping) Pressure (hypertension) Body mass index (>35) Age (>50) Neck size (>40 cm) Gender (male).

Table 1.

Essential components in clinical assessment in OSA—history

| History | History regarding the likelihood of OSA |

Snoring

Apnoea

|

| History regarding sleep architecture and hygiene |

Sleep hygiene

Sleep position

|

|

| History regarding consequences of OSA |

Waking/daytime

Weight

Cardiovascular/other conditions

|

|

| History regarding associated or adjunctive conditions |

Nasal symptoms

Thyroid symptoms

|

|

| History regarding previous treatment and assessments |

Prior PSG Prior CPAP/MAS/device use Prior/current downloads OTC/non‐prescribed medication Changes since prior evaluation |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; MVA, motor vehicle accident; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; OTC, over the counter; PSG, polysomnography.

Table 2.

Essential components in clinical assessment in OSA—examination

| Examination | General |

Weight, height, BMI Neck Blood pressure |

| Oral/oropharyngeal/dental |

Transoral Friedman stage/modified Mallampati Occlusion Maxilla/mandible Craniofacial Tonsil/palate/tongue |

|

| Nasal |

Anterior Nasal tip, nasal valve Mucosal disease Pathology |

|

| Nasendoscopy |

Structural/pathology Modified Mueller manoeuvre Woodson's hypotonic method Erect and supine Jaw thrust/Esmarch |

BMI, body mass index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

Table 3.

Essential components in clinical assessment in OSA—PSG

| PSG | |||

| If patients have high probability of OSA, they should have PSG prior to any pre‐phase nasal surgery | |||

| If patients have a low probability of OSA, and demonstrable nasal pathology, it may be reasonable to perform nasal surgery without PSG | |||

| Sleep physician assessment | Prior | Joint | Subsequent |

|

|

|

|

Assessment of severity.

LMO, Local Medical Officer; NREM, non‐REM; ODI, oxygen desaturation index; OHS, obesity hypoventilation syndrome; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; PSG, polysomnography; REM, rapid eye movement; RERA, respiratory effort‐related arousal; TST, total sleep time.

Table 4.

Preferred components in clinical assessment in OSA—questionnaires

| Acronym | Full name | Explanation/use |

|---|---|---|

| SSS | Snoring Severity Scale |

Incorporates elements of frequency, duration and loudness of snoring on a severity index of 9 (i) Can be difficult for patients who do not have a bed partner |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale | Questionnaire for evaluating degree of daytime sleepiness and extent of functional impairment, comprising eight questions whereby patients are asked to rate the likelihood of falling asleep on a scale of 0–3 in a range of sedentary situations, such as sitting and reading or watching television. Generally, an EES score >10 supports a diagnosis of EDS (ii) |

| FOSQ‐30/FOSQ‐10 | Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire‐30/or ‐10 |

Assesses the extent of functional impact of EDS across 30 items across five subscales (iii) The FOSQ‐10 is an abbreviated version of the instrument (iv) |

| OSA‐50 | Obstructive Sleep Apnoea‐50 | Screening tool for OSA, comprising four questions (v) |

| STOP‐BANG | Snoring Tired Observed (choking/gasping) Pressure (hypertension) Body mass index (>35) Age (>50) Neck size (>40 cm) Gender (male) | Utilized to determine risk of OSA and predict risk of post‐operative complications in individuals with OSA. Comprises eight items (vi) |

| Berlin | Berlin Questionnaire | Identification of OSA amongst the general population. Comprises 10 items across three domains of snoring severity, degree of daytime sleepiness and personal history of hypertension or obesity (vii) |

| SST | Sleep Surgery Tool—a medical checklist to review prior to operating. | Checklist (surgical) developed by Camacho et al.3 to highlight items to review prior to undertaking surgery (viii) |

Questionnaire completion—readers are urged to (a) check current MBS Guideline requirements for ordering polysomnography in relation to questionnaires, (b) consider some questionnaires (particularly i, ii and iii) as ‘before and after’ intervention assessments, (c) consider some questionnaires as screening tools (particularly iv, v and vi) and (d) carefully consider reasons to operate or not (particularly vii).

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

Table 5.

Optional components in clinical assessment in OSA (where required)

| Area | Optional evaluation | Explanation/components |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal investigations (if indicated) | RAST or SPT | Immunoglobulin E, house dust mite, grasses + pollens, animal mix/dander, moulds, food mix, others as suggested on history |

| CT paranasal sinuses | Evaluation of sino‐nasal disease where indicated | |

| Rhinomanometry | Predominantly a research tool, not routine in clinical practice | |

| Asleep dynamic assessment | SE or DISE |

Recommended in one of the four settings:

|

If proceeding, do so with:

|

||

|

Ideally, be familiar with

Prior polysomnogram |

||

| Cephalometrics/imaging | OPG/lateral cephalogram |

|

|

CT/MRI reconstruction protocolized images |

|

|

| Other multidisciplinary discussion/referral | MDT setting |

|

BIS, bispectral index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CT, computed tomography; DISE, drug‐induced sleep endoscopy; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; MDT, multidisciplinary team; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OPG, orthopantomogram; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; OT, Operating Theatre; RAST, radioallergosorbent test; SE, sleep nasendoscopy; SNA, subspinale angle; SNB, sella‐nasion‐supramentale angle; SPT, skin prick testing; TCI, target controlled infusion.

Desirable components: Collaboration with other professionals in OSA management

The committee notes that the following professionals treating OSA and associated conditions require different exposures for maintenance of skills and qualifications and that adult OSA is often a chronic progressive condition and may require complex combination therapy. 4

Dental

Trained in Twin‐Block titratable MAS

(Preferred) Member of the ASA/National/International Society

Orthodontist

Trained in Twin‐Block titratable MAS

(Preferred) Member of the ASA/National/International Society

Trained in pre‐maxillofacial surgery orthodontics and expansion orthodontics

Maxillofacial

Trained in bi‐maxillary advancement surgery, geniotubercle advancement and high sliding genioplasty

(Preferred) Member of the ASA/National/International Society

Sleep psychology

Trained in insomnia, distorted sleep architecture and multidisciplinary care

(Preferred) Member of the ASA/National/International Society

Surgeon

Trained in contemporary sleep surgery and multidisciplinary care

(Preferred) Member of the ASA/International Surgical Sleep Society (ISSS)/ASOHNS/other

Dietician/personal trainer (exercise physiologist)

Extended primary care healthcare plan compatible professionals

PRE‐ANAESTHESIA STUDIES

OSA carries increased perioperative risk. A discussion with anaesthesiologists is recommended preoperatively with regards to characteristics of OSA phenotype, such as arousal threshold and ventilatory stability, and also degree of arterial oxygen desaturation on polysomnogram, particularly oxygen nadir and duration of time spent below an peripheral oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) of 90%.

In obese patients and suggestive hypnogram, concurrent obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) should be suspected in patients with resting hypoxaemia, spirometry demonstrative of a restrictive ventilatory defect or elevated serum bicarbonate level (≥27 mEq/L). 6 In selected cases, arterial blood gas (ABG) sampling may be useful to establish daytime hypercapnia (arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) ≥ 45 mm Hg).

General pre‐anaesthetic evaluation should be carried out as per routine societal guidelines.

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT FOLLOWING OSA SURGERY

Ambulatory versus inpatient management

OSA is an established risk factor for increased incidence of perioperative complications, especially cardiopulmonary complications. 7 Preoperative evaluation of patient characteristics can assist with risk stratification and decision‐making regarding inpatient versus ambulatory management. 8

Optimal strategy for the preoperative identification of patients at high risk of compilations remains uncertain. 9 In addition to upper airway anatomical and neuromuscular factors, individual OSA phenotypic diversity encompasses arousal threshold and ventilatory stability, with specific OSA phenotypes potentially conferring increased perioperative vulnerability. 10

Perioperative risk stratification is required to balance patient safety and required location and intensity of post‐operative monitoring against cost and hospital resources, and should encompass patient characteristics, extent of upper airway surgery, requirement for opioid therapy and pain–sedation mismatch. 11

Patients with elevated body mass index (BMI), higher AHI or presence of multiple medical comorbidities have been identified as being at higher risk of early post‐operative complications following UPPP and, hence, should be recommended for overnight monitoring. 12 , 13 Preoperative AHI and extent of arterial oxygen desaturation are predictive of immediate post‐operative desaturation and respiratory compromise following isolated UPPP surgery. 14 Patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 and/or AHI ≥22/h are more likely to subsequently require supplemental oxygen therapy after transfer to the ward, and should receive more intensive monitoring. 12

The incidence of early post‐operative complications following isolated UPPP surgery is generally low. Importantly, reviews have consistently recognized that the majority of serious complications are identified within 3 h of surgery, highlighting the importance of careful observation during the immediate post‐operative period. 12 , 15 , 16 Generally, ongoing respiratory assessment in a post‐anaesthesia care unit (PACU) for at least 3 h can assist in early identification of upper airway instability or ventilatory vulnerability and requirement for a monitored bed and continuous pulse oximetry. 17 , 18 For ward‐based care, continued vigilance is encouraged across the initial 12–24‐h post‐operative period where risk of respiratory compromise is greatest. 19 , 20

Following ambulatory UPPP surgery, primary indications for unscheduled representations were primarily identified as haemorrhage (38.3%) and uncontrolled pain (21.2%). 21 Importantly, multilevel surgery for OSA, now considered standard practice, is associated with higher rates of complications compared to isolated UPPP, and more research is required to guide inpatient versus ambulatory management decisions. 22

Post‐operative CPAP therapy

Post‐operative disruption in sleep architecture is greatest across the first night, with a reduction in sleep efficiency, slow wave sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep occurring in both patients with and without OSA. 23 A significant increase in post‐operative AHI from baseline also occurs in patients with OSA, peaking on post‐operative night 3, which temporally corresponded to recovery in REM sleep. 23

The Society of Anaesthesia and Sleep Medicine (SASM) Practice Guidelines recommends that patients compliant with CPAP therapy should continue CPAP in the post‐operative period unless a specific contraindication is identified. 24

Whilst there is a paucity of evidence pertaining specifically to post‐operative CPAP management following corrective airway surgery for OSA, the ASA advises to assume the patient remains at heightened risk of perioperative OSA complications in the absence of a repeat normal PSG and resolution of symptoms. 11

Post‐operative analgesia

Multimodal analgesia should be considered standard of care following surgical treatment of OSA.

Within the first 12–24 h post‐operatively, use of systemic opioid therapy is associated with increased incidence of respiratory depression. 25 Most of the morbidity and mortality related to perioperative opioid‐induced respiratory depression relates to pain–sedation mismatch and insufficient monitoring, and are considered preventable. 19 , 20 Age, female gender and medical comorbidities are identified as risk factors for post‐operative opioid‐induced respiratory depression. 20 Certain OSA phenotypes with an elevated arousal threshold and reduced ventilatory response may be more vulnerable to opiate‐induced respiratory depression. 26

A multimodal strategy across classes and administration methods should be employed, inclusive of regional analgesia with local anaesthetic and systemic non‐opioid analgesia, such as paracetamol, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAID), cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors, pregabalin and gabapentin. 11

When opioids are administered, line‐of‐sight nursing care and continuous pulse oximetry monitoring are recommended with vigilance of pain–sedation mismatch. 11

Role of oxygen therapy

To manage early post‐operative hypoxaemia, continuous targeted supplemental oxygen can be utilized as an adjuvant to effective CPAP. Patients with high loop gain in particular can benefit from oxygen therapy, significantly reducing AHI and assisting ventilatory stability. 27

When oxygen therapy is utilized to treat early post‐operative hypoxaemia, flow rate should be titrated to a specified therapeutic range and continuous pulse oximetry monitoring is recommended. 11

In the setting of suspected or confirmed concurrent OHS, cautious administration of supplemental oxygen therapy is required to avoid hypoventilation and worsening of hypercapnia. 28

Patient position

Supine predominant or isolated OSA occurs in between 20% and 60% of individuals. 29 Post‐operatively, AHI is significantly elevated during supine sleep when compared to non‐supine sleep. 30

Non‐supine positioning is preferred throughout the recovery period to limit positional worsening of OSA. 11

Fluid management

Cautious use of perioperative intravenous fluid is encouraged. Significant increase in both neck circumference and post‐operative AHI has been demonstrated in males aged ≥40 years with infusion of normal saline (0.9% NaCl). 31 The combination of excessive intravenous fluid and rostral fluid shifts from immobilization, supine positioning and compression stockings can exacerbate post‐operative OSA. 32

Concluding remarks

Further research is required to guide the post‐operative management of patients following OSA surgery, particularly in the context of the transition from isolated to multilevel surgical procedures.

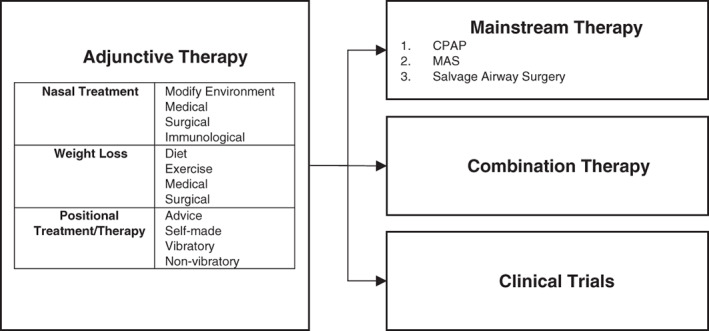

OVERALL THERAPY OUTLINE IN ADULT OSA MANAGEMENT

This overall therapy outline describes adjunctive, mainstream, combination and clinical trial pathways for Adult OSA patients (Fig. 2). Each treatment in these categories is described in detail below, with the exception of clinical trials. Where available and patient preference/clinician awareness dictates, clinical trial options of new or evolving treatment are encouraged.

Figure 2.

Overall therapy outline in adult OSA management: adjunctive, mainstream, combination therapy and clinical trials. CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

Nasal treatments: Pre‐phase (facilitatory)

In general, the committee recognizes the three main reasons why nasal treatments (below) should ideally precede other/subsequent interventions:

Reason 1: There may be a higher complication rate associated with concomitant nasal surgery (involving bony and cartilaginous work) and other airway surgery.

Reason 2: Nasal treatments may facilitate a return to device use/trial of devices again.

Reason 3: One may achieve a fortuitous outcome from nasal therapy alone, especially in milder forms of snoring and OSA, obviating the need for larger interventions.

The possible nasal treatments, to be applied singularly or in combination, as clinically indicated are listed below:

(i) Modifications for Management of Allergens

House dustmite (e.g. removal of bedroom carpets, high temperature bedding washes, etc.)

Grasses/pollens (e.g. protective masks during lawn‐mowing, etc.)

Moulds (e.g. cleaning environmental moulds, etc.)

Animal mix/dander (e.g. avoidance of specific household pets, etc.)

(ii) Medical

Preventer medication (eg. Topical Corticosteroid Spray, Montelukast Inhibitor)

Reliever medication (eg. Antihistamines, Saltwater Douche)

Preventer/reliever medication (eg. Topical corticosteroid/Antihistamine spray)

(iii) Surgical

Septoplasty/septal reconstruction

Turbinate reduction

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery

Nasal valve surgery/(or ‘dilators’)

(iv) Immunological

Immunomodulatory medication

Sublingual immunotherapy

Injection immunotherapy

Weight loss treatment (adjunctive)

Given that obesity is the major risk factor for OSA, 33 weight loss is an important treatment strategy that is relevant for the majority of patients with OSA. The relationship between weight loss and OSA (and other OSA treatments) is complex and bi‐directional. 34 , 35 A number of studies have demonstrated that weight loss via various methods can have an important impact on OSA, 36 , 37 although even dramatic weight loss may not completely resolve OSA. In this context, following weight loss, patients with residual OSA who desire additional treatment may be considered as candidates for airway surgery or other therapy.

The potential weight loss strategies, singularly or in combination, in adult OSA patients are listed below:

Dietary interventions

Advice

Dietician

Concomitant/metabolic disease

Exercise interventions

Advice

Exercise physiologist

Concomitant/metabolic disease

Surgical interventions

Minimal

Laparoscopic/sleeve

Bypass

Medical/hormonal

Medicines

Hormonal/endocrine

Positional treatment/therapy

Positional therapy is a cost‐effective and low‐risk alternative (or adjunctive) treatment for OSA. Up to 20% of patients with OSA experience respiratory events exclusively in the supine sleeping position 38 , 39 and therefore may achieve resolution of OSA when they avoid supine sleep. 40 , 41 The preferred method of supine position avoidance is with the use of vibratory warning devices which allow patients to move freely when asleep and deliver warning vibrations when the patient has adopted the supine sleeping position. Devices that use discomfort to prompt avoidance of the supine position (such as the ‘tennis ball technique’) have poor long‐term adherence 42 whilst bolster or pillow arrangements can leave patients stuck on one side all night increasing the chance of hip and shoulder discomfort.

The potential positional therapy options and strategies in adult OSA patients are listed below:

-

Advice/self‐manufacturable

Advice

Blocks or prods

Tennis ball

-

Positional devices (vibratory)

Nightshift (downloadable data available)

BuzzPOD

Sleep Position Trainer

-

Positional devices (non‐vibratory)

Zzoma

Rematee

Other

Combination therapy

As many of the non‐CPAP therapies for OSA are often only partially effective in treating the disease, there has been a focus on combining treatments to improve efficacy. The rationale is that because OSA has many contributory mechanisms including unfavourable airway anatomy, poor upper airway dilator muscle response, respiratory control instability and low respiratory arousal threshold; combining treatments that target one or more of these mechanisms could result in improved treatment results. For example, the combination of upper airway surgery and supine position avoidance (both anatomical treatments 43 , 44 ) is frequently recommended based on the observation that upper airway surgery for OSA preferentially reduces the lateral AHI 45 and that positional avoidance can be used to further improve symptoms. 46 A similar approach may be efficacious in patients who have undergone significant weight loss with a concomitant improvement in lateral AHI. 47 Further research is exploring the possibility of targeting different OSA mechanistic pathways. For example, upper airway surgery does not alter respiratory control instability (or loop gain) 48 and treatments that improve respiratory control stability could be utilized to further improve the AHI in patients who have had upper airway surgery with residual OSA symptoms.

The potential combination therapy options and strategies in adult OSA patients are listed below:

Combination pre‐phase/adjunctive treatments

Nasal treatment + weight loss + positional therapy

Nasal treatment + weight loss

Nasal treatment + positional therapy

Weight loss + positional therapy

Combination adjunctive and mainstream treatment

Weight loss + surgery

Weight loss + MAS

Nasal treatment + surgery

Nasal treatment + MAS

Positional therapy + surgery

Positional therapy + MAS

Combination mainstream treatments

Surgery + MAS

‘Mainstream’ therapy

Continuous positive airway pressure

CPAP is the gold standard treatment for OSA. A number of guidelines exist that describe the management of OSA with CPAP therapy. 49 , 50 The position paper of the ASA on CPAP therapy can be found at https://www.sleep.org.au/documents/item/66. RCT evidence exists to support the positive effect of CPAP on mood and cognition; however, the cardiovascular benefits of this treatment remain in doubt. 51 Certainly, CPAP is limited in its application by a high number of patients who cannot comply with the therapy long term. 52 For those patients encountering difficulties acclimatizing to CPAP secondary to nasal obstruction, nasal surgery can be an important intervention to facilitate increased CPAP compliance. 53 Counter to this, some of the older forms of palatal surgery are associated with difficulty subsequently using CPAP therapy. 54 We recommend that patients being considered for upper airway (UA) surgery to reduce OSA severity have an adequate trial of CPAP therapy prior to surgery. We consider a 3–6‐month trial of supervised CPAP treatment mandatory except where patients have very favourable anatomy with a high probability of improvement with operative intervention.

The potential CPAP therapy options in adult OSA patients are listed below:

Nasal CPAP

Nasal pillows CPAP

Full face mask CPAP

Oral mask CPAP

Mandibular advancement splint

Twin‐Block titratable MAS are an efficacious treatment for OSA. 55 A number of society guidelines exist for the implementation of these treatments. 56 , 57 However, the treatment is not universally successful and comes with potential side effects such as temporomandibular joint pain and bite misalignment. 58 As with surgery, selecting the correct patients for this anatomical treatment remains an ongoing issue. 59

Surgery

The next section of this consensus statement contains key algorithms, as guidance for practicing sleep surgeons in Australasia, in the assessment and execution of operative (and other) interventions.

The algorithms have been designed specifically to assist sleep surgeons in approaches to commonly faced scenarios. However, heterogeneity/complexity of anatomy, physiology, airway dynamics, surgical skill and patient preference mean that these algorithms are a guide, not prescriptive.

The algorithms are based on the assimilation of all available levels of evidence, predominately in adult airway sleep surgeries, recognizing that RCT are rarely done in surgery, but that those available have been considered.

Multiple other non‐randomized controlled publications have been taken into account, as defined acceptable by the Consensus Writing Committee (with experienced sleep surgeons and sleep physicians involved) and the ASA Clinical Committee, and categorized into A, B, C, D and E in Appendix S1 (Supplementary Information).

It is noted that the effect sizes on AHI and other parameters in many of these papers, particularly the systematic review/meta‐analyses, are large. Such large effect sizes are seen to justify the categorization and weightings applied to them in Appendix S1 (Supplementary Information).

Despite this, surgery carries risk (see Complications of pharyngeal surgery for snoring/OSA section) and further longer term studies in the field remain warranted.

It should also be noted that many newer areas in the field, particularly hypoglossal nerve stimulator implantation, are in evolution and increased access and availability are anticipated beyond 2020 in Australasia.

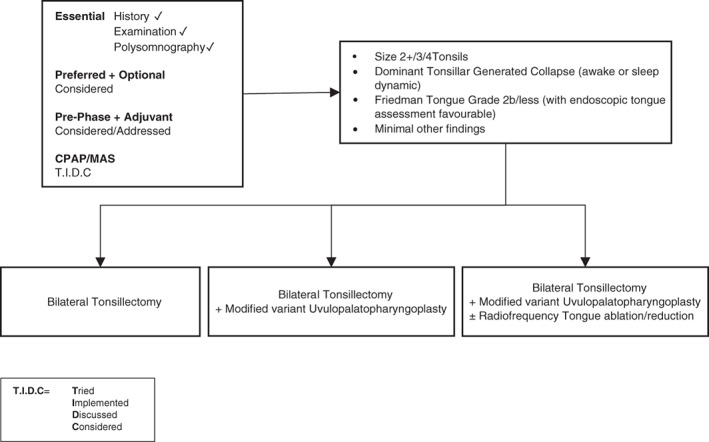

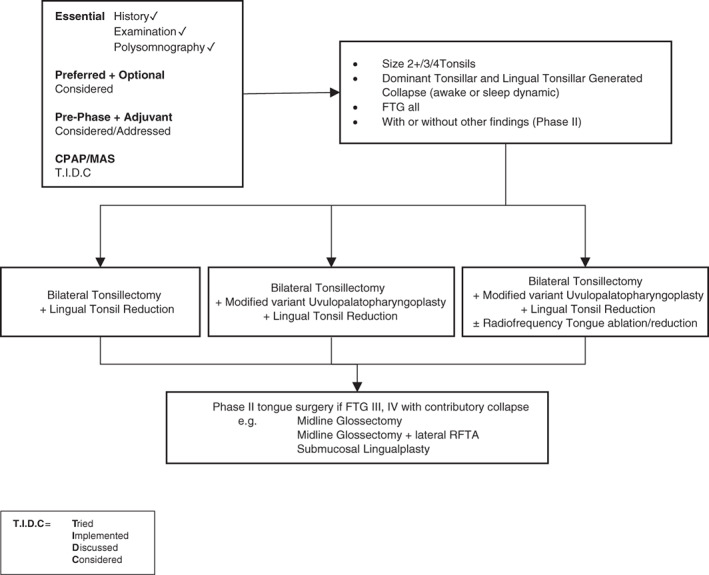

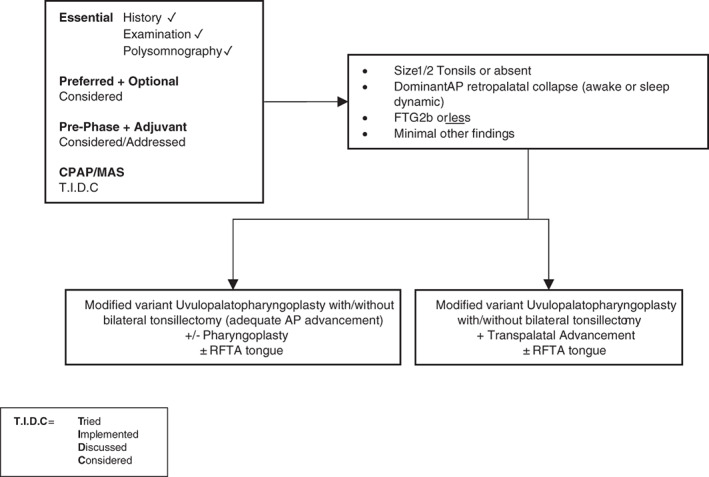

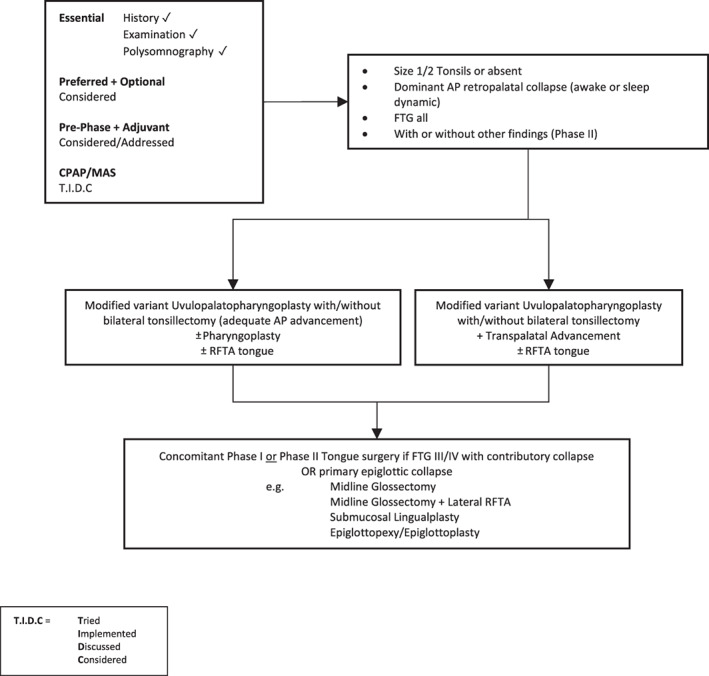

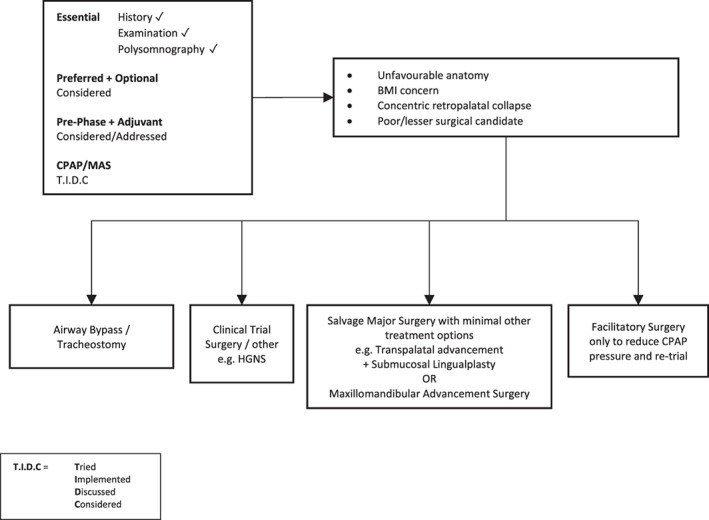

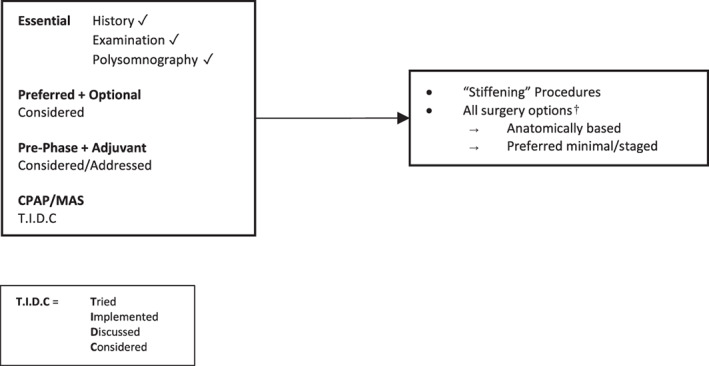

In Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, suggested algorithms with surgical options (each figure based upon differing anatomical variations) are outlined for adult patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA. In Figure 8, options for mild OSA/snoring are provided. It is accepted there may be exceptional circumstances under which mild OSA/snoring patients are sufficiently symptomatic to warrant following Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

Figure 3.

Surgery #1. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA (and anatomy as per this figure). CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

Figure 4.

Surgery #2. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA (and anatomy as per this figure). CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FTG, Friedman tongue position; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; RFTA, radiofrequency tissue ablation.

Figure 5.

Surgery #3. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA (and anatomy as per this figure). CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FTG, Friedman tongue position; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; RFTA, radiofrequency tissue ablation.

Figure 6.

Surgery #4. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA (and anatomy as per this figure). CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FTG, Friedman tongue position; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; RFTA, radiofrequency tissue ablation.

Figure 7.

Surgery #5. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly moderate to severe OSA (and anatomy as per this figure). BMI, body mass index; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HGNS, hypoglossal nerve stimulation; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

Figure 8.

Surgery #6. Algorithm for adult OSA surgery in patients with predominantly mild OSA or ‘snoring without OSA’. CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; MAS, mandibular advancement splint; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea.

COMPLICATIONS OF PHARYNGEAL SURGERY FOR SNORING/OSA

The known post‐operative complications related to pharyngeal/airway surgeries are listed below. It is recommended that surgeons performing any of the interventions in this position statement familiarize themselves with the ‘early’ and ‘late’ complications, and adhere to the follow‐up/outcomes guide listed below.

Early post‐operative

Bleeding

Airway compromise: swelling ± opioid effect. Steroids (i.v.) are beneficial in the first 48–72 h. If patient is still using CPAP prior to surgery, immediate post‐operative use is suggested in patients with an elevated BMI

Infection

Wound dehiscence: partial dehiscence of the UPPP incision is common, and usually heals well by secondary intention

Complications of all surgeries: (pulmonary embolism (PE), myocardial infarction (MI), anaphylaxis, etc.)

Late post‐operative

Secondary haemorrhage: typically days 7–10 post‐operatively

Velopharyngeal incompetence: rare with newer modified UPPP variants. Swallowing exercises (e.g. Mendelsohn manoeuvre) usually resolve this

Palatal fistula: uncommonly seen after transpalatal advancement. Usually heals with conservative management. May require a temporary splint. Rarely, a local flap may be needed

Change in taste: this is usually subtle, and often slowly resolves over 12 months

Change in swallowing: very subtle changes in swallowing are fairly common (e.g. to dry crumbly food). As with taste changes, these often resolve over a year, but may persist to a very subtle degree long term

Follow‐up/outcomes assessment

PSG: 3–4 months post‐operatively, 12 months post‐operatively, then as indicated

Epworth and snoring severity scale: 3–4 months, 12 months, then annually. Preoperative assessments should be repeated post‐operatively

Other symptomatic assessment: Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), 10 or 30: pre‐ and post‐operatively as described above

Annual clinical review is recommended

It is advised that resection or ablative procedures involving Laser are avoided as unpredictable scar, pain and many of the above‐listed risks are of greater likelihood. 3

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The committee recognizes the following four important future directions:

-

1

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation

This is a surgically implantable, medically titratable device. Upper airway stimulation (UAS) is a surgically implanted device that induces neuromuscular augmentation of the hypoglossal nerve and genioglossus muscle timed with ventilation or set off a duty cycle. UAS reduces multilevel collapse to increase retropalatal and retrolingual dimensions. 60 It is commercially available internationally, but remains in clinical trial phase in Australasia. UAS has been incorporated into the German guideline for management of sleep‐disordered breathing. 61 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has yet to incorporate UAS into their guideline recommendations.

Evaluation of the evidence for UAS

The STAR multicentre prospective cohort study evaluated patients with a BMI ≤32 kg/m2 with moderate to severe OSA and intolerance or poor compliance with CPAP therapy treated with a unilateral hypoglossal nerve implant (Inspire Medical Systems, Minneapolis, MN). 62 The 5‐year follow‐up of the STAR study indicated that patients treated with hypoglossal nerve stimulation (HGNS) maintained improvements in PSG parameters (AHI and oxygen desaturation index (ODI)) and patient‐focused measures (Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and FOSQ) of OSA. 63 The median AHI decreased from a baseline value of 29.3 to 6.2 and median ODI from 25.4 to 4.6. Median ESS decreased from 11 at baseline to 6 and median FOSQ increased from 14.6 to 18.7. Incidence of device‐related adverse events were low at 6% and all related to lead or device adjustments.

The multicentre single‐arm German post‐market study enrolled patients with a BMI ≥15 and ≤65 kg/m2 who received the UAS system (Inspire Medical Systems). 64 At 12 months, median (interquartile range (IQR)) AHI had reduced from 28.6 (21.6–40.1) to 9.5 (4.6–18.6), ESS had reduced from 13 (9.5–17) to 6.5 (3–10), and FOSQ had increased from 13.7 (11.3–16.7) to 18.6 (16.1–19.7).

Results from the retrospective and prospective ADHERE Registry of 10 tertiary care hospitals in Germany and the USA (no BMI limit) showed significant improvement in both objective and patient‐reported OSA outcomes, demonstrating a decrease from baseline to the post‐titration review in mean AHI (±SD) of 35.6 ± 15.3 to 10.2 ± 12.9 (P < 0.0001), and a decrease in ESS score from 11.9 ± 5.5 to 7.5 ± 4.7 (P < 0.0001). 65

In Australia, the Genio‐Nyxoah system offering bilateral nerve stimulation with an implantable device, triggered by an external stimulator set off a duty cycle, has recent publications to support a role in OSA therapy, 66 with a further study (‘BETTER SLEEP’) underway.

Further research is required to establish the efficacy of UAS in comparison to the various OSA surgical procedures.

Patient selection for UAS

Patient selection for UAS should encompass assessment for features predictive of likely success. 67 , 68 , 69 Drug‐induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) in the supine position to exclude patients with complete concentric collapse, an unfavourable pattern to UAS success, is recommended, but based on limited data. 70 Computed tomography imaging has been determined to offer limited value to predict responders to UAS and cannot be recommended currently. 68 , 71

-

2

Robotic upper airway surgery

Appropriately credentialed surgeons with expertise in robotic surgery may intervene with such technology, based on a published systematic review and meta‐analysis.

-

3

Phenotyping/endo‐phenotyping and personalized approaches

Selecting patients for surgical intervention based on features such as pharyngeal critical pressure (Pcrit) and low loop gain may become a part of future paradigms in Australasia.

-

4

Standardization and registries for data collection

Future registries via International Surgical Sleep Society, ASA, ASOHNS and New Zealand Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (NZSOHNS) are likely to support the audit and refinement of surgical procedures.

KEY POINTS.

A comprehensive and targeted history and examination is essential for optimal patient selection in the application of OSA surgery.

Consideration of medical comorbidities and other sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy and depression, is critical prior to commitment to OSA surgery given potential for reversible elements, and in such circumstances, referral for formal sleep physician assessment is preferred.

Formal PSG is deemed necessary prior to consideration of OSA surgery and review of current Medicare guidelines is recommended when requesting PSG.

Questionnaire tools can assist in evaluating ‘before’ and ‘after’ outcomes in OSA surgery, establishing functional impact, and determining perioperative risk attributable to the presence of OSA, and their incorporation in routine assessment is preferred.

Targeted nasal investigations (such as allergy profiling and radiological imaging) are considered optional in the presence of relevant clinical and examination findings.

Sleep nasendoscopy is not considered part of routine clinical assessment, and its role is yet to be validated. Sleep nasendoscopy is therefore considered optional.

Discussion regarding standard non‐surgical options to manage OSA is essential. The risks and benefits of each option should be conveyed to the patient.

Collaborative perioperative management is essential, given the presence of OSA confers increased perioperative risk.

Importantly, there is no single airway examination or assessment tool predictive of surgical outcome. Rather, it is a combination of considered and individualized assessment elements.

Nasal surgery can be considered a facilitatory treatment option in select patients.

Awareness of appropriate anatomically directed, multilevel surgical options is recommended in the treatment of adult OSA patients seeking salvage surgery.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Categories of evidence supporting a role for OSA surgery in adults.

MacKay SG, Lewis R, McEvoy D, Joosten S, Holt NR. Surgical management of obstructive sleep apnoea: A position statement of the Australasian Sleep Association. Respirology. 2020;25:1292–1308. 10.1111/resp.13967

*This position statement has been formulated by the Australasian Sleep Association Surgical Writing Group, and has been reviewed and approved by the Australasian Sleep Association.

Handling Editors: Philip Bardin and Paul Reynolds

Contributor Information

Stuart G. MacKay, sgmackay@ozemail.com.au.

Nicolette R. Holt, Email: nicolette.holt@mh.org.au.

REFERENCES

- 1. MacKay S, Carney AS, Catcheside PG, Chai‐Coetzer CL, Chia M, Cistulli PA, Hodge JC, Jones A, Kaambwa B, Lewis R et al Effect of multilevel upper airway surgery vs medical management on the apnea‐hypopnea index and patient‐reported daytime sleepiness among patients with moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea: the SAMS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacKay S, Jefferson N, Jones A, Sands T, Woods C, Raftopulous M. Benefit of a contemporary sleep multidisciplinary team (MDT): patient and clinician evaluation. J. Sleep Disor. Treat. Care 2014; 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Camacho M, Riley RW, Capasso R, O'Connor P, Chang ET, Reckley LK, Guilleminault C. Sleep surgery tool: A medical checklist to review prior to operating. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017; 45: 381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kezirian EJ, Hohenhorst W, de Vries N. Drug‐induced sleep endoscopy: the VOTE classification. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011; 268: 1233–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heatley EM, Harris M, Battersby M, McEvoy RD, Chai‐Coetzer CL, Antic NA. Obstructive sleep apnoea in adults: a common chronic condition in need of a comprehensive chronic condition management approach. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013; 17: 349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mokhlesi B, Masa JF, Brozek JL, Gurubhagavatula I, Murphy PB, Piper AJ, Tulaimat A, Afshar M, Balachandran JS, Dweik RA et al Evaluation and management of obesity hypoventilation syndrome. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019; 200: e6–e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Opperer M, Cozowicz C, Bugada D, Mokhlesi B, Kaw R, Auckley D, Chung F, Memtsoudis SG. Does obstructive sleep apnea influence perioperative outcome? A qualitative systematic review for the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine Task Force on preoperative preparation of patients with sleep‐disordered breathing. Anesth. Analg. 2016; 122: 1321–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holt NR, Downey G, Naughton MT. Perioperative considerations in the management of obstructive sleep apnoea. Med. J. Aust. 2019; 211: 326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ayas NT, Laratta CR, Coleman JM, Doufas AG, Eikermann M, Gay PC, Gottlieb DJ, Gurubhagavatula I, Hillman DR, Kaw R et al; ATS Assembly on Sleep and Respiratory Neurobiology. Knowledge gaps in the perioperative management of adults with obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018; 15: 117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subramani Y, Singh M, Wong J, Kushida CA, Malhotra A, Chung F. Understanding phenotypes of obstructive sleep apnea: applications in anesthesia, surgery, and perioperative medicine. Anesth. Analg. 2017; 124: 179–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea . Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 268–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kandasamy T, Wright ED, Fuller J, Rotenberg BW. The incidence of early post‐operative complications following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: identification of predictive risk factors. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013; 42: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kezirian EJ, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson WG. Risk factors for serious complication after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006; 132: 1091–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JA, Lee JJ, Jung HH. Predictive factors of immediate postoperative complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 1837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spiegel JH, Raval TH. Overnight hospital stay is not always necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pang KP. Identifying patients who need close monitoring during and after upper airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2006; 120: 655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gali B, Whalen FX, Schroeder DR, Gay PC, Plevak DJ. Identification of patients at risk for postoperative respiratory complications using a preoperative obstructive sleep apnea screening tool and postanesthesia care assessment. Anesthesiology 2009; 110: 869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weingarten TN, Kor DJ, Gali B, Sprung J. Predicting postoperative pulmonary complications in high‐risk populations. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2013; 26: 116–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee LA, Caplan RA, Stephens LS, Posner KL, Terman GW, Voepel‐Lewis T, Domino KB. Postoperative opioid‐induced respiratory depression: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology 2015; 122: 659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gupta K, Prasad A, Nagappa M, Wong J, Abrahamyan L, Chung FF. Risk factors for opioid‐induced respiratory depression and failure to rescue: a review. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2018; 31: 110–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bhattacharyya N. Revisits and readmissions following ambulatory uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope 2015; 125: 754–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Friedman JJ, Salapatas AM, Bonzelaar LB, Hwang MS, Friedman M. Changing rates of morbidity and mortality in obstructive sleep apnea surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017; 157: 123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung F, Liao P, Yegneswaran B, Shapiro CM, Kang W. Postoperative changes in sleep‐disordered breathing and sleep architecture in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 287–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chung F, Memtsoudis SG, Ramachandran SK, Nagappa M, Opperer M, Cozowicz C, Patrawala S, Lam D, Kumar A, Joshi GP et al Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine guidelines on preoperative screening and assessment of adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesth. Analg. 2016; 123: 452–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramachandran SK, Haider N, Saran KA, Mathis M, Kim J, Morris M, O'Reilly M. Life‐threatening critical respiratory events: a retrospective study of postoperative patients found unresponsive during analgesic therapy. J. Clin. Anesth. 2011; 23: 207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lam KK, Kunder S, Wong J, Doufas AG, Chung F. Obstructive sleep apnea, pain, and opioids: is the riddle solved? Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2016; 29: 134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, Stevenson KE, Gautam S, White DP. Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008; 162: 144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mokhlesi B, Tulaimat A, Parthasarathy S. Oxygen for obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a double‐edged sword? Chest 2011; 139: 975–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dieltjens M, Braem MJ, Van de Heyning PH, Wouters K, Vanderveken OM. Prevalence and clinical significance of supine‐dependent obstructive sleep apnea in patients using oral appliance therapy. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014; 10: 959–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung F, Liao P, Elsaid H, Shapiro CM, Kang W. Factors associated with postoperative exacerbation of sleep‐disordered breathing. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yadollahi A, Gabriel JM, White LH, Taranto Montemurro L, Kasai T, Bradley TD. A randomized, double crossover study to investigate the influence of saline infusion on sleep apnea severity in men. Sleep 2014; 37: 1699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lam T, Singh M, Yadollahi A, Chung F. Is perioperative fluid and salt balance a contributing factor in postoperative worsening of obstructive sleep apnea? Anesth. Analg. 2016; 122: 1335–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bearpark H, Elliott L, Grunstein R, Hedner J, Cullen S, Schneider H, Althaus W, Sullivan C. Occurrence and correlates of sleep disordered breathing in the Australian town of Busselton: a preliminary analysis. Sleep 1993; 16: S3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joosten SA, Hamilton GS, Naughton MT. Impact of weight loss management in OSA. Chest 2017; 152: 194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ong CW, O'Driscoll DM, Truby H, Naughton MT, Hamilton GS. The reciprocal interaction between obesity and obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Med Rev. 2013; 17: 123–31. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kansanen M, Vanninen E, Tuunainen A, Pesonen P, Tuononen V, Hartikainen J, Mussalo H, Uusitupa M. The effect of a very low‐calorie diet‐induced weight loss on the severity of obstructive sleep apnoea and autonomic nervous function in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Clin. Physiol. 1998; 18: 377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dixon JB, Schachter LM, O'Brien PE, Jones K, Grima M, Lambert G, Brown W, Bailey M, Naughton MT. Surgical vs conventional therapy for weight loss treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 308: 1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joosten SA, Hamza K, Sands S, Turton A, Berger P, Hamilton G. Phenotypes of patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea as confirmed by cluster analysis. Respirology 2012; 17: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mador MJ, Kufel TJ, Magalang UJ, Rajesh SK, Watwe V, Grant BJB. Prevalence of positional sleep apnea in patients undergoing polysomnography. Chest 2005; 128: 2130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bignold JJ, Mercer JD, Antic NA, McEvoy RD, Catcheside PG. Accurate position monitoring and improved supine‐dependent obstructive sleep apnea with a new position recording and supine avoidance device. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011; 7: 376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barnes H, Edwards BA, Joosten SA, Naughton MT, Hamilton GS, Dabscheck E. Positional modification techniques for supine obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2017; 36: 107–115. 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bignold JJ, Deans‐Costi G, Goldsworthy MR, Robertson CA, McEvoy D, Catcheside PG, Mercer JD. Poor long‐term patient compliance with the tennis ball technique for treating positional obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2009; 5: 428–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Joosten SA, Edwards BA, Wellman A, Turton A, Skuza EM, Berger PJ, Hamilton GS. The effect of body position on physiological factors that contribute to obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2015; 38: 1469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwartz AR, Schubert N, Rothman W, Godley F, Marsh B, Eisele D, Nadeau J, Permutt L, Gleadhill I, Smith PL. Effect of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1992; 145: 527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravesloot MJL, Benoist L, van Maanen P, de Vries N. Novel positional devices for the treatment of positional obstructive sleep apnea, and how this relates to sleep surgery. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2017; 80: 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Benoist LBL, Verhagen M, Torensma B, van Maanen JP, de Vries N. Positional therapy in patients with residual positional obstructive sleep apnea after upper airway surgery. Sleep Breath. 2017; 21: 279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Joosten SA, Khoo JK, Dixon JB, Naughton MT, Edwards BA, Hamilton GS. The relationship between weight loss and non‐supine apnea‐hypopnea index. D57 don't be a do‐badder: new interventions for OSA. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016; 193: A7463. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Joosten SA, Leong P, Landry, SA , Sands SA, Terrill PI, Mann DL, Turton A, Rangaswamy J, Andara C, Burgess G et al Loop gain predicts the response to upper airway surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. In: Sleep. 2017; Vol. 40, No. 7 10.1093/sleep/zsx094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M, Morgenthaler TI, Alessi CA, Bailey D, Boehlecke B, Brown TM, Coleman J Jr, Friedman L et al Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep‐related breathing disorders. Sleep 2006; 29: 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fleetham J, Ayas N, Bradley D, Fitzpatrick M, Oliver TK, Morrison D, Ryan F, Series F, Skomro R, Tsai W; Canadian Thoracic Society Sleep Disordered Breathing Committee. Canadian Thoracic Society 2011 guideline update: diagnosis and treatment of sleep disordered breathing. Can. Respir. J. 2011; 18: 25–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, Luo Y, Ou Q, Zhang X, Mediano O, Chen R, Drager LF, Liu Z et al; SAVE Investigators and Coordinators. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016; 375: 919–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, Redline S, Henry JN, Getsy JE, Dinges DF. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993; 147: 887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Poirier J, George C, Rotenberg B. The effect of nasal surgery on nasal continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Laryngoscope 2014; 124: 317–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mortimore IL, Bradley PA, Murray JA, Douglas NJ. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty may compromise nasal CPAP therapy in sleep apnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996; 154: 1759–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gotsopoulos H, Chen C, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002; 166: 743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, Lettieri CJ, Harrod CG, Thomas SM, Chervin RD. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: an update for 2015. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015; 11: 773–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ngiam J, Balasubramaniam R, Darendeliler MA, Cheng AT, Waters K, Sullivan CE. Clinical guidelines for oral appliance therapy in the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Aust. Dent. J. 2013; 58: 408–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sutherland K, Cistulli P. Mandibular advancement splints for the treatment of sleep apnea syndrome. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2011; 141: w13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Edwards BA, Andara C, Landry S, Sands SA, Joosten SA, Owens RL, White DP, Hamilton GS, Wellman A. Upper‐airway collapsibility and loop gain predict the response to oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016; 194: 1413–22. 10.1164/rccm.201601-0099OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Safiruddin F, Vanderveken OM, de Vries N, Maurer JT, Lee K, Ni Q, Strohl KP. Effect of upper‐airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnoea on airway dimensions. Eur. Respir. J. 2015; 45: 129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mayer G, Arzt M, Braumann B, Ficker JH, Fietze I, Frohnhofen H, Galetke W, Maurer JT, Orth M, Penzel T et al German S3 guideline nonrestorative sleep/sleep disorders, chapter "sleep‐related breathing disorders in adults," short version: German Sleep Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin, DGSM). Somnologie (Berl.) 2017; 21: 290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Strollo PJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, de Vries N, Cornelius J, Froymovich O, Hanson RD, Padhya TA, Steward DL, Gillespie MB et al; STAR Trial Group. Upper‐airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014; 370: 139–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Woodson BT, Strohl KP, Soose RJ, Gillespie MB, Maurer JT, de Vries N, Padhya TA, Badr MS, Lin HS, Vanderveken OM et al Upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea: 5‐year outcomes. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018; 159: 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Steffen A, Sommer JU, Hofauer B, Maurer JT, Hasselbacher K, Heiser C. Outcome after one year of upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea in a multicenter German post‐market study. Laryngoscope 2018; 128: 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boon M, Huntley C, Steffen A, Maurer JT, Sommer JU, Schwab R, Thaler E, Soose R, Chou C, Strollo P et al; ADHERE Registry Investigators. Upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea: results from the ADHERE Registry. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018; 159: 379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Eastwood PR, Barnes M, MacKay SG, Wheatley JR, Hillman DR, Nguyên XL, Lewis R, Campbell MC, Pételle B, Walsh JH, Jones AC, Palme CE, Bizon A, Meslier N, Bertolus C, Maddison KJ, Laccourreye L, Raux G, Denoncin K, Attali V, Gagnadoux F, Launois SH. Bilateral hypoglossal nerve stimulation for treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2020; 55: 1901320 10.1183/13993003.01320-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Heiser C, Hofauer B. Predictive success factors in selective upper airway stimulation. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol Relat. Spec. 2017; 79: 121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Steffen A. What makes the responder to upper airway stimulation in obstructive sleep apnea patients with positive airway pressure failure? J. Thorac. Dis. 2018; 10: S3131–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Heiser C, Steffen A, Boon M, Hofauer B, Doghramji K, Maurer JT, Sommer JU, Soose R, Strollo PJ Jr, Schwab R et al; ADHERE Registry Investigators. Post‐approval upper airway stimulation predictors of treatment effectiveness in the ADHERE Registry. Eur. Respir. J. 2019; 53: 1801405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vanderveken OM, Maurer JT, Hohenhorst W, Hamans E, Lin HS, Vroegop AV, Anders C, de Vries N, Van de Heyning PH. Evaluation of drug‐induced sleep endoscopy as a patient selection tool for implanted upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013; 9: 433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schwab RJ, Wang SH, Verbraecken J, Vanderveken OM, Van de Heyning P, Vos WG, DeBacker JW, Keenan BT, Ni Q, DeBacker W. Anatomic predictors of response and mechanism of action of upper airway stimulation therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2018; 41 10.1093/sleep/zsy021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Categories of evidence supporting a role for OSA surgery in adults.