Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association of skilled nursing facility (SNF) quality with days spent alive in nonmedical settings (“home time”) after SNF discharge to the community.

Data Sources

Secondary data are from Medicare claims for New York State (NYS) Medicare beneficiaries, the Area Health Resources File, and Nursing Home Compare.

Study Design

We estimate home time in the 30‐ and 90‐day periods following SNF discharge. Two‐part zero‐inflated negative binomial regression models characterize the association of SNF quality with home time.

Data Extraction Methods

We use Medicare claims data to identify 25 357 NYS fee‐for‐service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older with an SNF admission for postacute care who were subsequently discharged to home in 2014.

Principal Findings

Following 30 and 90 days after SNF discharge, the average home time is 28.0 (SD = 6.1) and 81.6 (SD = 20.2) days, respectively. A number of patient‐ and SNF‐level factors are associated with home time. In particular, within 30 and 90 days of discharge, respectively, patients discharged from 2‐ to 5‐star SNFs spend 1.2‐1.5 (P < .001) and 3.2‐4.3 (P < .001) more days at home than those discharged from 1‐star (lowest quality) SNFs.

Conclusions

Improved understanding of what is contributing to differences in home time could help guide efforts into optimizing post‐SNF discharge outcomes.

Keywords: aging in place, care transitions, postacute care, quality of care, rehabilitation

What This Study Adds.

Prior work has shown that Medicare beneficiaries admitted to higher‐quality skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) have favorable outcomes such as decreased mortality, fewer days in the SNF, fewer hospital readmissions, and more time in the community.

This study builds upon prior work by characterizing how SNF quality impacts home time among postacute care SNF patients who are discharged home.

After accounting for patient‐, SNF‐, and community‐level factors, we find that patients discharged from 2‐ to 5‐star SNFs spend 1.2‐1.5 (P < .001) and 3.2‐4.3 (P < .001) more days at home than those discharged from 1‐star SNFs over 30 and 90 days following SNF discharge, respectively.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2018, about 1.6 million fee‐for‐service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries used skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) at least once. 1 Following a medically necessary hospitalization of three or more days, Medicare will cover up to 100 days of qualified postacute SNF care, and 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries discharged from hospitals are admitted to SNFs for postacute care. 1 Postacute care was the fastest growing Medicare spending category from 1994 to 2009. 2 In 2017, Medicare FFS spending on SNF services was $28.4 billion with a median payment per stay of $18 121. 1

Although most SNF residents prefer to return to the community, we know little about the factors affecting the SNF‐to‐home transition. Many older adults admitted to SNFs are not discharged to the community (one estimate is that about 1 in 2 of nursing facility admissions are not discharged to the community within 12 months). 3 , 4 Even among those discharged from the SNF, many struggle with the transition back to the community (eg, 22.1 percent visit the ED and/or are hospitalized within 30 days of SNF discharge). 5 , 6 Furthermore, post‐SNF discharge outcomes, such as rates of potentially avoidable hospital readmissions within 30 days after SNF discharge, vary widely across higher‐ and lower‐performing SNFs, 1 suggesting that SNF quality may impact patients following SNF discharge. Indeed, emerging evidence indicates SNF quality is associated with a variety of outcomes including mortality, days in the SNF, hospital readmissions, and time in the community. 7 Moreover, vulnerable patients, such as racial and ethnic minorities, Medicaid patients, and patients with behavioral health disorders face barriers to accessing high‐quality SNFs, and even within the same SNFs, racial and ethnic minority patients can have worse outcomes. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

Postacute care discharge outcomes traditionally are measured by health events such as ED visits, hospital readmissions, and/or mortality. There is increasing interest, however, in focusing on patient‐centered endpoints and treatment goals. 14 , 15 A highlighted priority of patients and caregivers is days spent at home (“home time”). 16 Home time can be calculated from Medicare claims data by examining the number of days alive that were spent outside of a hospital, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or SNF over a specified period. 17 While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) now report on the rate of successful discharges to the community from SNFs (ie, discharged to the community without unplanned readmissions or death within 31 days after discharge), 1 this metric captures information different than what home time examines. For example, in contrast to CMS’ successful discharge metric, home time focuses solely on patients who have been discharged to the community. Home time also more comprehensively examines the degree to which discharge has been a success (rather than considering successful discharge as a discrete event free from unplanned rehospitalizations). Home time has been assessed for stroke patients 18 and is increasingly being examined in different populations such as patients who are terminal, 16 heart failure, 17 and surgical patients. 19 A recent examination of home time demonstrated that it is associated with other patient‐centered outcomes such as self‐rated health, mobility impairment, depression, self‐care difficulty, and limited social activity. 20

Examination of home time following discharge from postacute care SNF admissions to the community has been limited. Among patients admitted to an SNF for postacute care, higher SNF star ratings are associated with decreased mortality, fewer days in the SNF, fewer hospital readmissions, and more days at home or with home health care. 7 Building upon this prior work, this study focuses specifically on the post‐SNF discharge period and assesses home time and the factors associated with its duration among Medicare beneficiaries discharged from SNF to the community in New York State (NYS). We hypothesize that, after controlling for patients’ health and functional status, older adults discharged from higher‐quality SNFs spend more days in the community compared with individuals discharged from lower‐quality SNFs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data sources

We use 2014 data from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File (MedPAR), 21 the Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF), 22 the Medicare Outpatient Revenue Center File, 23 the Long‐Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0, 24 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’(CMS) FY 2014 Final Rule Tables, 25 the Area Health Resources File (AHRF), 26 and the Nursing Home Compare (NHC) file managed by CMS. 27 The Medicare‐based administrative datasets (eg, MedPAR, MBSF, MDS, Outpatient Revenue Center File) are derived from claims submitted by health providers and institutions. To obtain these datasets, we entered into a Data Use Agreement with CMS and subsequently purchased them from CMS. The University of Rochester Institutional Review Board and the Privacy Board at CMS approved this study.

2.2. Sample

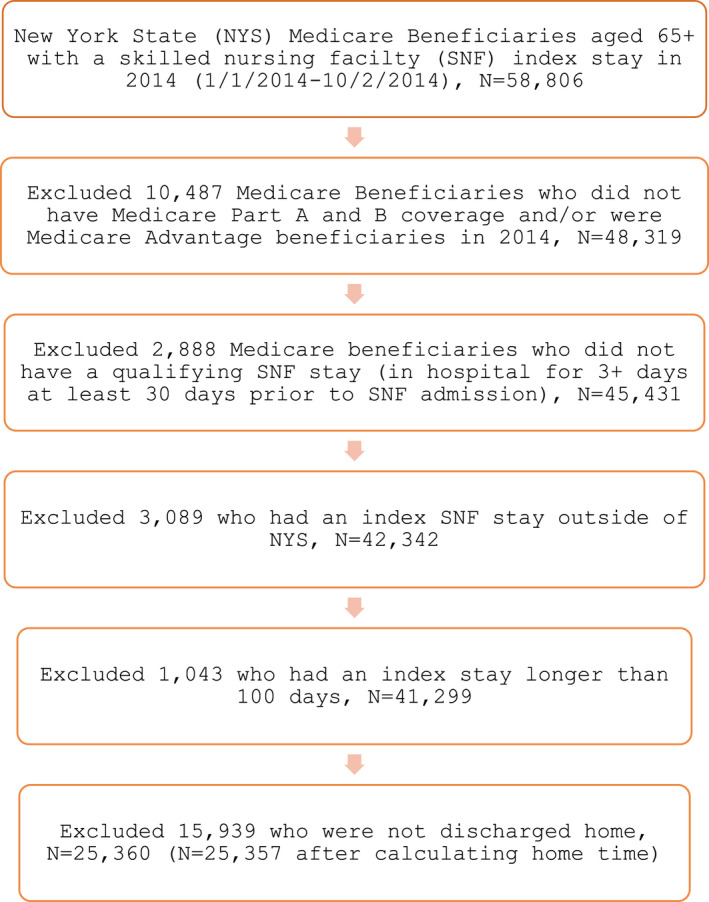

Our retrospective cohort consists of all NYS FFS Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older with an index NYS SNF admission in 2014 following a hospitalization of three or more days. We define the index SNF admission as being the first SNF admission in 2014 not preceded by an SNF admission in the prior three months. We include beneficiaries who were discharged to the community within 100 days of the SNF admission. We follow all discharged residents for 90 days post‐SNF discharge, and to do so, we only include residents discharged from the SNF between January 1, 2014, and October 2, 2014. Figure 1 shows the cohort selection process. Among the 15 939 older adults not discharged home, 10 517 (66.0 percent) were discharged to a hospital, 1622 (10.2 percent) died, 1937 (12.2 percent) remained an SNF patient, and 1863 (11.7 percent) had a variety of other discharge locations (eg, hospice, transfer to another SNF). Of note, we limit our cohort to FFS beneficiaries because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have incomplete records on hospitalization (necessary for identifying a postacute stay and for calculating home time), and we do not have their outpatient medical claims data (necessary for calculating home time as these data capture emergency department observation stays).

FIGURE 1.

Cohort selection for older adult New York State (NYS) fee‐for‐service Medicare beneficiaries who had an index NYS skilled nursing facility admission in 2014 and were subsequently discharged home. We exclude Medicare Advantage beneficiaries because their outpatient claims data are not available and hospitalization records are incomplete. Notes: Based on authors’ analysis of the Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, and the Long‐Term Care Minimum Data Set 3.0 datasets, 2014 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.3. Outcome

We assess home time using MedPAR, MBSF, and outpatient revenue center files by calculating the number of days a patient is alive and not in a hospital (either acute inpatient admission or an observation stay), an inpatient rehabilitation setting, or a SNF, which is similar to previous studies. 17 We focus on two home time windows—30 and 90 days—following SNF discharge to the community.

2.4. Key independent variable

The key independent variable of interest in our study is SNF quality measured by the CMS’ 5‐star overall rating. 28 The overall quality rating is a composite score based on health inspections, quality of resident care measures, and staffing levels. The health inspections quality metric is based on the number, scope, and severity of SNF deficiencies identified via yearly heath inspections and from complaints or facility‐reported incidents over the prior three years. The quality of resident care metric is based on 11 quality measures obtained from MDS assessments. The staffing quality metric is based on the registered nurse as well as total staffing hours per resident day. 29 A 1‐ to 5‐star rating system assesses each domain, with more stars denoting fewer health deficiencies, higher staffing per resident day, and better quality of care. Of note, while CMS instituted the SNF Value‐Based Purchasing Program in 2018, a national program rewarding SNFs with incentive payments based on 30‐day all cause readmissions, 30 in 2014 SNF quality metrics did not account for discharge outcomes. We use the 5‐star overall quality rating in this study because it is a summary score of different quality domains and has been shown to be relevant to a variety of patient outcomes (eg, 5‐star overall rating has been linked to mortality and days in the SNF 7 ). For our cohort, the 5‐star overall rating distribution among the 626 NYS SNFs is 9.6 percent (1 star), 22.2 percent (2 stars), 17.7 percent (3 stars), 22.4 percent (4 stars), and 28.1 percent (5 stars). Similar to other studies, 13 to facilitate comparisons across SNF quality ratings, we collapsed SNFs into fewer categories (1‐star, 2‐ to 3‐star, and 4‐ to 5‐star groupings).

2.5. Covariates

We include patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors as covariates because prior research suggests that there are a wide variety of factors that can affect an older adult's ability to remain in the community. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 Patient‐level factors consist of sociodemographic characteristics, health status and functioning, and other medical information (see Appendix S1: Table A1 for covariates and corresponding datasets). Sociodemographic characteristics consist of age (MedPAR 21 ), marital status (MDS 24 ), and sex, race, and Medicaid dual eligibility (MBSF 22 ). Health status and functioning include number of medical conditions (MedPAR 21 ), Alzheimer's disease, or dementia (MDS, 24 MedPAR 21 ) as well as cognitive functioning as assessed by the Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) scores 36 and physical functioning as determined by activities of daily living scores (0‐28; higher scores indicate greater functional impairment) (MDS 24 ). 37 , 38 Other medical information considers the number of days in the hospital prior to SNF admission (MedPAR 21 ), whether the hospitalization prior to SNF admission was for a medical or surgical reason (CMS FY 2014 Final Rule Tables 25 ), and the number of days in the SNF (MedPAR 21 ). These data come from a combination of sources (MedPAR, 21 MBSF, 22 MDS 24 ).

SNF‐level factors include ownership, occupancy, total licensed nursing hours per resident day, nurse aid nursing hours per resident day, and hospital‐based versus freestanding SNF (NHC file 27 ).

County‐level variables (linked to SNF county of residence) include metro vs. nonmetro county (determined by Rural‐Urban Commuting Codes) and the supply of primary care physicians, hospital beds, SNF beds, and home health agencies per 100 000 people (AHRF 26 ).

2.6. Analyses

We first examine the distributions of 30‐ and 90‐day home time and other patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors across SNFs with overall star ratings of 1 star, 2‐3 stars, and 4‐5 stars. We use chi‐square and analysis of variance for statistical inference as appropriate. We then fit separate multivariable regression models to assess the relationship between SNF quality of care and home time in the 30‐ and 90‐day time windows.

Our home time outcome measures are highly skewed in both the 30‐ and 90‐day follow‐up periods (see Appendix S1: Figure A1). Thus, in multivariable analyses we model facility days (by subtracting home time from 30 and 90, respectively) using zero‐inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression models to account for the high number of patients having zero facility days (or, inversely, “perfect” home time) and overdispersion in the count of days. 39 The ZINB regression has two parts. The first part is a generalized linear model with a logit link function and assuming binomial distribution, which estimates the likelihood of a patient having zero facility days. The second part is a count model assuming a negative binomial distribution, which estimates the number of facility days conditional on facility admission. Models in both parts have dummy variables for SNF star ratings (1‐star SNFs as the omitted group) as the key independent variable and control for the same patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level covariates. After model estimation, we calculate and report the marginal effects of higher star ratings on days spent at home (ie, the inverse of the originally estimated effects on facility days). We conduct analyses at the beneficiary level using SAS software version 9.4 and STATA version 12.1.

3. STUDY RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

Among all beneficiaries, those discharged from the SNF to home (N = 25 357) have a mean age of 81.7 years; 66.1 percent are female, 15.6 percent are non‐white, 34.6 percent are married, 25.0 percent are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and 19.2 percent have a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or dementia. Across all SNFs, most beneficiaries have perfect home times of 30 (83.6 percent) and 90 (70.6 percent) days following SNF discharge; 10.1 percent and 20.3 percent had an ED visit with no hospitalization, 13.7 percent and 25.4 percent were hospitalized, 5.8 percent and 11.8 percent were readmitted to a SNF, and 2.4 percent and 6.1 percent died within 30 and 90 days of SNF discharge to the community, respectively. Most beneficiaries (64.6 percent) were discharged from 4‐ to 5‐star SNFs. There are no statistically significant differences in the beneficiaries’ sex, marital status, Medicaid dual eligibility status, or cognitive functioning score by SNF quality (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics of the New York State fee‐for‐service Medicare beneficiaries stratified by skilled nursing facility quality

| 1‐star SNF (N = 1651) | 2‐ to 3‐star SNF (N = 7272) | 4‐ to 5‐star SNF (N = 16 372) | P‐value (χ 2 or ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or prevalence | ||||

| Patient factors | ||||

| Age | 80.66 ± 8.66 | 81.57 ± 8.48 | 81.81 ± 8.45 | <.0001 |

| Female | 64.99% | 65.24% | 66.61% | .0723 |

| Non‐white | 9.51% | 11.45% | 18.03% | <.0001 |

| Married | 33.43% | 34.63% | 34.71% | .4331 |

| Medicaid dual eligible | 24.17% | 24.45% | 25.29% | .2823 |

| Alzheimer's disease/dementia | 16.78% | 19.02% | 19.58% | .0192 |

| Days in SNF | 26.24 ± 18.46 | 27.53 ± 18.99 | 27.93 ± 18.91 | .0016 |

| Days spent in hospital prior to SNF stay | 7.32 ± 6.09 | 7.08 ± 6.55 | 6.84 ± 5.92 | .0007 |

| Perfect 30‐d home time | 78.13% | 82.60% | 84.58% | <.0001 |

| Perfect 90‐d home time | 66.20% | 68.99% | 71.72% | <.0001 |

| Average 30‐d home time | 26.69 ± 8.07 | 27.91 ± 6.10 | 28.10 ± 5.86 | <.0001 |

| Average 90‐d home time | 78.41 ± 24.42 | 81.45 ± 20.16 | 81.95 ± 19.65 | <.0001 |

| Number of diagnoses | 4.20 ± 3.57 | 5.81 ± 3.30 | 6.21 ± 3.77 | <.0001 |

| Medical DRG prior to SNF stay | 59.72% | 59.38% | 56.61% | <.0001 |

| Died within 30 d | 3.69% | 2.35% | 2.34% | .0026 |

| Died within 90 d | 7.51% | 6.48% | 5.76% | .0044 |

| No outpatient ED visit in 30 d | 89.64% | 88.41% | 90.56% | <.0001 |

| No outpatient ED visit in 90 d | 77.83% | 77.63% | 80.81% | <.0001 |

| No hospital stay in 30 d | 81.28% | 85.67% | 87.07% | <.0001 |

| No hospital stay in 90 d | 70.62% | 73.67% | 75.48% | <.0001 |

| No SNF stay in 30 d | 90.98% | 94.11% | 94.64% | <.0001 |

| No SNF stay in 90 d | 85.16% | 88.08% | 88.57% | <.0001 |

| Admitting diagnosis | ||||

| Neoplasms | 2.12% | 1.66% | 1.60% | <.0001 |

| Endocrine, metabolic, immunity disorders | 3.03% | 4.51% | 2.68% | |

| Nervous system and sense organs | 2.24% | 1.88% | 1.50% | |

| Circulatory system diseases | 15.26% | 13.22% | 12.69% | |

| Respiratory system diseases | 7.15% | 5.53% | 5.51% | |

| Digestive system diseases | 4.12% | 3.19% | 2.66% | |

| Genitourinary system diseases | 4.18% | 3.58% | 2.91% | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue diseases | 2.54% | 1.82% | 1.52% | |

| Musculoskeletal system diseases | 19.50% | 15.03% | 12.62% | |

| Injury and poisoning | 9.45% | 10.51% | 8.36% | |

| Other | 30.41% | 39.08% | 47.95% | |

| Brief Interview for Mental Status score | 13.02 ± 3.26 | 13.08 ± 3.20 | 13.03 ± 3.27 | .5030 |

| Functional Status Scale | 12.89 ± 6.34 | 14.11 ± 5.77 | 15.44 ± 5.31 | <.0001 |

| SNF factors | ||||

| For profit | 68.50% | 51.66% | 44.41% | <.0001 |

| Occupancy | 0.97 ± 0.81 | 0.93 ± 0.24 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | <.0001 |

| Total licensed nursing hours per resident day | 1.45 ± 0.19 | 1.56 ± 0.39 | 1.78 ± 0.82 | <.0001 |

| Nurse aid nursing hours per resident day | 2.26 ± 0.30 | 2.39 ± 0.39 | 2.47 ± 0.47 | <.0001 |

| Hospital‐based | 3.82% | 9.09% | 13.36% | <.0001 |

| County factors | ||||

| Metro | 87.34% | 86.47% | 97.53% | <.0001 |

| Primary care physicians rate per 100 000 | 92.46 ± 35.09 | 81.07 ± 29.85 | 97.34 ± 36.26 | <.0001 |

| Hospital beds rate per 100 000 | 370.97 ± 170.08 | 357.37 ± 161.03 | 321.66 ± 138.86 | <.0001 |

| SNF beds rate per 100 000 | 716.82 ± 214.72 | 634.05 ± 173.05 | 583.09 ± 119.80 | <.0001 |

| Home health agencies rate per 100 000 | 1.25 ± 0.66 | 0.92 ± 0.62 | 0.87 ± 0.47 | <.0001 |

Based on authors’ analysis of the Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, Long‐Term Care Minimum Data Set 3.0, revenue center file, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ FY 2014 Final Rule Tables and Nursing Home Compare file, and the Area Health Resources File, 2014. Some factors are missing observations.

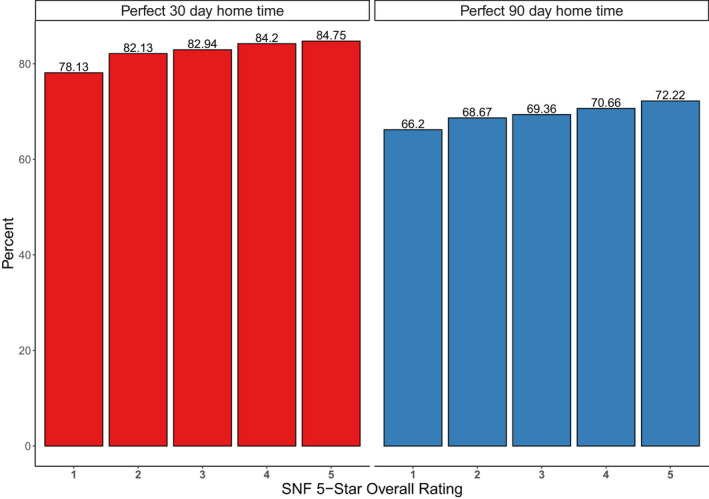

There are differences across SNF overall quality ratings. Specifically, home time varies across overall quality ratings with perfect 30‐ and 90‐day home times and mean home times increasing with higher SNF quality ratings (Table 1). Similarly, mortality is lower for higher‐quality SNFs and post‐SNF discharge ED visits with no hospitalization, hospitalization, and SNF readmissions occur less frequently for higher‐quality SNFs (Table 1). Figure 2 shows that the 2‐ to 5‐star SNFs have 4.0‐6.6 and 2.5‐6.0 higher absolute percentages in 30‐ and 90‐day perfect home times, respectively, than the 1‐star SNFs.

FIGURE 2.

The proportion of beneficiaries with perfect 30‐ and 90‐day home time by SNF 5‐star overall rating. Notes: Based on authors’ analysis of the Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, revenue center file, and the Long‐Term Care Minimum Data Set 3.0 datasets, and Nursing Home Compare file, 2014. For perfect 30‐day home time, the number of beneficiaries discharged from 1‐, 2‐, 3‐, 4‐, and 5‐star SNFs was 1290, 3216, 2791, 4382, and 9465, respectively. For perfect 90‐day home time, the number of beneficiaries discharged from 1‐, 2‐, 3‐, 4‐, and 5‐star SNFs was 1093, 2683, 2334, 3667, and 8065, respectively [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Relationships between 30‐ and 90‐day home time and associated factors

The estimated marginal effects for our key independent variable of interest (SNF overall star rating) from zero‐inflated negative binomial regression models for 30‐ and 90‐day home time follow‐up periods are shown in Table 2 (see Appendix S1: Table A2 for a complete listing of marginal effects for all covariates). After accounting for patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors, compared with beneficiaries discharged from 1‐star SNFs, those discharged from 2‐ to 5‐star SNFs spend an additional 1.2‐1.5 days at home in the 30‐day follow‐up period and an additional 3.2‐4.3 days at home in the 90‐day follow‐up period (Table 2). Due to concerns for possible collinearity between SNF overall quality rating and the staffing covariates, we conducted a multivariable analysis with the two staffing‐level covariates removed. SNF overall quality's association with home time was not changed materially in these analyses (see Appendix S1: Table A3).

TABLE 2.

Associations of home time with SNF 5‐star overall ratings

| 30‐d home time | 90‐d home time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effect (P‐value) | 95% CI | Marginal effect (P‐value) | 95% CI | |

| Overall star rating: 2 stars (ref = 1 star) | 1.18 (<.001) | 0.67, 1.70 | 3.18 (<.001) | 1.51, 4.85 |

| Overall star rating: 3 stars (ref = 1 star) | 1.18 (<.001) | 0.66, 1.71 | 3.34 (<.001) | 1.64, 5.03 |

| Overall star rating: 4 stars (ref = 1 star) | 1.50 (<.001) | 0.99, 2.00 | 4.10 (<.001) | 2.47, 5.74) |

| Overall star rating: 5 stars (ref = 1 star) | 1.50 (<.001) | 0.99, 2.00 | 4.31 (<.001) | 2.68, 5.93 |

| Observations used | 23 460 | 23 285 | ||

Based on authors’ analysis of the Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, Long‐Term Care Minimum Data Set 3.0, revenue center file, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ FY 2014 Final Rule Tables and Nursing Home Compare file, and the Area Health Resources File, 2014. Marginal effects estimated from zero‐inflated negative binomial regression models for home time in the 30‐ and 90‐d follow‐up periods; regression models accounted for patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors. The estimates show, for example, that compared to beneficiaries discharged from 1‐star SNFs, those discharged from 5‐star SNFs spent an additional 1.50 d at home in the 30‐d follow‐up period, or an additional 4.31 d at home in the 90‐d follow‐up period.

We find similar patient‐level factors and associations in both the 30‐ and 90‐day follow‐up periods. Consistent with the home time findings, many of the 90‐day estimated effects are proportional to the 30‐day findings and correspond to the differences in the length of follow‐up (eg, 90‐day estimates are approximately threefold larger than 30‐day estimates) (Appendix S1: Table A2). Non‐white and female beneficiaries spend an additional 1.5‐2.0 days at home in the 90‐day follow‐up period (ME: 1.50, P‐value: <.001; ME: 2.00, P‐value: <.001, respectively). Those with Alzheimer's disease/dementia or who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, however, spend 1.0‐1.7 fewer days at home in the 90‐day follow‐up period (ME: −1.00, P‐value: .016; ME: −1.69, P‐value: <.001, respectively), and those whose hospital admission was medical (compared with surgical) have a 5 day shorter home time over 90 days (ME: −5.13, P‐value: <.001) (Appendix S1: Table A2).

4. DISCUSSION

Building upon recent work by Cornell et al, which examined trajectories of patients admitted to SNF for postacute care, 7 we narrow the focus and examine home time following SNF discharge to the community among older adult FFS Medicare beneficiaries. Congruent with our hypothesis, we find that SNF quality matters with regard to home time. Interestingly, while 1‐star quality SNFs have appreciable differences in home time when compared to the 2‐ to 5‐star quality SNFs, the gap between home times among the 2‐ to 5‐star quality SNFs is more incremental. For example, when comparing 5‐star quality SNFs to 1‐ and 2‐star quality SNFs in the 90 days following a SNF discharge to the community, those discharged from the 5‐star SNF spend 4.3 and 1.1 more days at home, respectively, after controlling for patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors. Although 1.5 and 4.3 more home time days (when comparing 5‐star to 1‐star SNFs) may seem like modest differences, a study that examined home time's association with functional decline and death found a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in home time of 18.6 days over 365 days of follow‐up. 20 When proportionately adjusting for the differences in follow‐up time, our findings are at or near this reported MCID. Accounting for patient characteristics in our analyses is important because the patient populations served by higher‐ and lower‐quality SNFs may systematically differ. 40 A prior study examining the association of SNF quality with hospital readmission found that, in unadjusted analyses, SNF quality measures are linked to hospital readmissions or death, but that this association is considerably attenuated after accounting for patient and facility factors. 41 In contrast, in our study the association of SNF quality with home time persists even after accounting for other factors. Moreover, our study suggests that the effect of SNF quality may extend well beyond the time spent in the SNF.

Although the reasons why SNF overall quality is associated with home time are unclear, there are several plausible explanations. For instance, perhaps lower‐quality SNFs have worse discharge planning and/or less coordination of care with primary care physicians and home health services. Additional efforts are needed to examine why home time varies across SNFs because, consistent with prior research, 5 our study finds that many older adults fare poorly following SNF discharge (eg, many utilize ED services or are hospitalized). An improved understanding of why home time varies across SNFs may in turn identify intervention or quality improvement targets to help these vulnerable older adults transition home. Another consideration is that our datasets lack information on characteristics that can affect an older adults’ ability to live in the community. For example, we do not have information on the presence of a caregiver or the home living arrangement, which can affect the risk of SNF admission and long‐term care placement. 34 , 42 Without this information, we are unable to examine whether the increased home time in higher‐quality SNFs may be due in part to differences in the presence of caregivers or home living arrangement (eg, perhaps beneficiaries from 1‐star‐rated nursing homes have lower levels of caregiver support).

In addition to overall SNF quality, this study finds numerous patient‐level factors that are associated with the amount of time older adults spend at home following SNF discharge. Notably, older adults who are male are Medicaid dual eligible, have dementia, and with a pre‐SNF hospitalization for a medical (rather than surgical) reason, spend 2.0, 1.7, 1.0, and 5.1 fewer days in the community in the 90 days following SNF discharge, respectively. While we accounted for many patient‐level factors, there nonetheless may be important unaccounted for differences between the patients admitted to low‐ and high‐quality nursing homes, which may impact discharge outcomes. For example, as publicly reported quality measures are increasingly emphasized, SNFs may avoid certain patient populations (such as those with behavioral health needs) in an effort to enhance their quality scores. 13 , 43 Additionally, there are disparities in accessing high‐quality SNFs. 8 , 9 , 13 , 44 Awareness of these and other patient‐level factors may be of utility in informing discharge planning and identifying which patients are at elevated risk of poor outcomes following discharge to the community.

Older adults in postacute care settings are high utilizers of health services, and the impetus to improve outcomes, enhance quality of care, and reduce costs for this population is substantial. With the increasing number of medically complex older adults receiving rehabilitation services in postacute care settings, developing interventions that enhance quality of care and improve outcomes could have considerable public health benefits (eg, improve functional status and independence, reduce utilization of costly acute medical and custodial SNF services). Although limited evidence suggests that care transition interventions may increase discharges to the community 45 or improve post‐SNF discharge outcomes, 46 the vast majority of care transitions interventions has been focused on discharges from the hospital rather than from the SNF. 47 There is little empirical evidence to guide us on how to assist these older adults with the SNF‐to‐home transition. Nonetheless, the necessity of improving post‐SNF discharge outcomes is becoming more urgent as CMS has been pursuing alternative payment methods that incentivize the quality of care while attempting to reduce overall health care costs. For example, CMS launched the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative that provides a lump‐sum payment for an episode of care. 48 , 49 Recently, CMS also has adopted the Skilled Nursing Facility Value‐Based Purchasing Program, which has incentivized payments based on hospital readmission rates. 50

Our study has several strengths. First, we examine a patient‐centered outcome that focuses on the time older adults spend alive in nonmedical settings, a measure that has not received much prior investigation and a topic for which relatively little is known. Second, we utilize a large cohort of older adults in NYS who received postacute care in SNFs, controlling for patient‐, SNF‐, and county‐level factors, and identify characteristics associated with home time.

There are several limitations in our study. Perhaps most notably, there are limitations in claims data, and we are missing information on important characteristics such as living arrangement and social support that may affect post‐SNF discharge home outcomes. For example, we do not know whether the beneficiaries have caregivers present. Furthermore, claims datasets include information recorded for purposes of reimbursement rather than for research purposes, which may affect data completeness and validity. Our study likewise does not have information to provide more context to the time older adults spend at home such as assessments of their quality of life (eg, increased home time may not be a uniformly positive outcome if older adults are struggling in their homes). Another limitation is that our study only has information for NYS Medicare beneficiaries and is geographically limited. Future work should consider examining post‐SNF discharge home time in a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries. An additional limitation is that we excluded Medicare Advantage beneficiaries because we do not have information necessary to identify a postacute SNF admission and to calculate home time. Future studies should also examine how utilization of outpatient and in‐home services may affect home time.

Although home time is a patient‐centered outcome that intrinsically reflects traditionally reported outcomes such as hospitalization and mortality, it has been infrequently utilized. For example, not only does home time capture whether a patient dies or is rehospitalized, but also it is more nuanced and comprehensive in that it considers the length of time that a patient is alive as well as the duration of the hospitalization. Expanding the use of home time as a clinical outcome should be considered. Home time is also promising because it is a continuous measure and may be better able to demonstrate whether an intervention or quality improvement effort is effective than a more traditional binary outcome measure. Lastly, building off this current study, further investigation as to why there are disparities in home time following discharge from lower‐ and higher‐quality SNFs is needed. Improved understanding of what is contributing to these differences would help guide efforts into optimizing post‐SNF discharge outcomes for all patients, especially since vulnerable populations are disproportionately represented in lower‐quality SNFs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

YL serves as an editor for Springer and a consultant for BCG Inc and Intermountain Healthcare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. AS developed the study concept and design and had primary responsibility for preparing the manuscript. JO had primary responsibility for data management and analyses. All authors assisted with the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising of the manuscript, and critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Supporting information

Author Matrix

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: AS was supported through the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program, sponsored by the New York State Department of Health as well as by the National Institute on Aging (grant number K23AG058757). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health. YL serves as an editor for Springer and a consultant for BCG Inc. and Intermountain Healthcare, and there are no other disclosures to report.

Simning A, Orth J, Temkin‐Greener H, Li Y. Patients discharged from higher‐quality skilled nursing facilities spend more days at home. Health Serv Res.2021;56:102–111. 10.1111/1475-6773.13543

Prior Presentation: We presented some of this article's findings at Academy Health's Annual Research Meeting in Washington, DC, on June 2, 2019.

REFERENCES

- 1. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in Medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff. 2013;32(5):864‐872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hakkarainen TW, Arbabi S, Willis MM, Davidson GH, Flum DR. Outcomes of patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities after acute care hospitalizations. Ann Surg. 2016;263(2):280‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gassoumis ZD, Fike KT, Rahman AN, Enguidanos SM, Wilber KH. Who transitions to the community from nursing homes? Comparing patterns and predictors for short‐stay and long‐stay residents. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2013;32(2):75‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, et al. Restarting the cycle: Incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):79‐85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simning A, Caprio TV, Seplaki CL, Conwell Y. Rehabilitation providers' prediction of the likely success of the SNF‐to‐home transition differs by discipline. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(4):492‐496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cornell PY, Grabowski DC, Norton EC, Rahman M. Do report cards predict future quality? The case of skilled nursing facilities. J Health Econ. 2019;66:208‐221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Konetzka RT, Grabowski DC, Perraillon MC, Werner RM. Nursing home 5‐star rating system exacerbates disparities in quality, by payer source. Health Aff. 2015;34(5):819‐827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zuckerman RB, Wu S, Chen LM, Joynt Maddox KE, Sheingold SH, Epstein AM. The five‐star skilled nursing facility rating system and care of disadvantaged populations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):108‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rivera‐Hernandez M, Rahman M, Mor V, Trivedi AN. Racial disparities in readmission rates among patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(8):1672‐1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hefele JG, Wang XJ, Lim E. Fewer bonuses, more penalties at skilled nursing facilities serving vulnerable populations. Health Aff. 2019;38(7):1127‐1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Y, Cai X, Glance LG. Disparities in 30‐day Rehospitalization rates among Medicare skilled nursing facility residents by race and site of care. Med Care. 2015;53(12):1058‐1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Temkin‐Greener H, Campbell L, Cai X, Hasselberg MJ, Li Y. Are post‐acute patients with behavioral health disorders admitted to lower‐quality nursing homes? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(6):643‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient‐reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):575‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. PROMIS: Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Health Measures. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore‐measurement‐systems/promis. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 16. Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days spent at home — a patient‐centered goal and outcome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1610‐1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greene SJ, O'Brien EC, Mentz RJ, et al. Home‐time after discharge among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(23):2643‐2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mishra NK, Shuaib A, Lyden P, et al. Home time is extended in patients with ischemic stroke who receive thrombolytic therapy: a validation study of home time as an outcome measure. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1046‐1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Myles PS, Shulman MA, Heritier S, et al. Validation of days at home as an outcome measure after surgery: A prospective cohort study in Australia. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee H, Shi SM, Kim DH. Home time as a patient‐centered outcome in administrative claims data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(2):347‐351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ResDAC . MedPAR. https://www.resdac.org/cms‐data/files/medpar. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 22. ResDAC . Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base. https://www.resdac.org/cms‐data/files/mbsf‐base. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 23. ResDAC . Revenue Center File. https://www.resdac.org/cms‐data/files/op‐encounter/data‐documentation. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 24. ResDAC . Long Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0. https://www.resdac.org/cms‐data/files/mds‐3.0. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 25. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . FY 2014 Final Rule Tables. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare‐Fee‐for‐Service‐Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY‐2014‐IPPS‐Final‐Rule‐Home‐Page‐Items/FY‐2014‐IPPS‐Final‐Rule‐CMS‐1599‐F‐Tables.html. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- 26. Health Resources & Services Administration . Area Health Resources Files. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health‐workforce/ahrf. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 27. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Nursing Home Compare Data Archive: 2014 Data. https://data.medicare.gov/data/archives/nursing‐home‐compare. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- 28. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Design for Nursing Home Compare Five‐Star Quality Rating System, technical users' guide. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider‐Enrollment‐and‐Certification/CertificationandComplianc/downloads/usersguide.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2019.

- 29. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Fact Sheet: Nursing Home Compare Five‐Star Quality Rating System. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider‐Enrollment‐and‐Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/consumerfactsheet.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2019.

- 30. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . The Skilled Nursing Facility Value‐Based Purchasing (SNF VBP) Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/Value‐Based‐Programs/SNF‐VBP/SNF‐VBP‐Page.html. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 31. Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S.: a meta‐analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS. Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):560‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palmer JL, Langan JC, Krampe J, et al. A model of risk reduction for older adults vulnerable to nursing home placement. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2014;28(2):162‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cepoiu‐Martin M, Tam‐Tham H, Patten S, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Predictors of long‐term care placement in persons with dementia: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(11):1151‐1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang SY, Shamliyan TA, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Not just specific diseases: systematic review of the association of geriatric syndromes with hospitalization or nursing home admission. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(1):16‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saliba D, Buchanan J, Edelen MO, et al. MDS 3.0: brief Interview for Mental Status. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):611‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539‐1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546‐M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greene WH. Econometric Analysis, 3rd edn Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice‐Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across U.S. nursing homes. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):1448‐1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542‐1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jorgensen TSH, Allore H, MacNeil Vroomen JL, Wyk BV, Agogo GO. Sociodemographic factors and characteristics of caregivers as determinants of skilled nursing facility admissions when modeled jointly with functional limitations. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1599‐1604.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sewell DD.Nursing homes are turning away patients with mental health issues. Care for Your Mind. Care for Your Mind Web site. http://careforyourmind.org/nursing‐homes‐are‐turning‐away‐patients‐with‐mental‐health‐issues/. Accessed September 23, 2019.

- 44. Wang Y, Zhang Q, Spatz ES, et al. Persistent geographic variations in availability and quality of nursing home care in the United States: 1996 to 2016. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hass Z, Woodhouse M, Grabowski DC, Arling G. Assessing the impact of Minnesota's return to community initiative for newly admitted nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(3):555‐563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toles M, Colon‐Emeric C, Asafu‐Adjei J, Moreton E, Hanson LC. Transitional care of older adults in skilled nursing facilities: a systematic review. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(4):296‐301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kansagara D, Chiovaro J, Kagen D, et al. Transitions of care from hospital to home: A summary of systematic evidence reviews and recommendations for transitional care in the Veterans Health Administration. 2014. [PubMed]

- 48. Cen X, Temkin‐Greener H, Li Y. Medicare bundled payments for post‐acute care: characteristics and baseline performance of participating skilled nursing facilities. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;77(2):155‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled‐payments/. Accessed May 24, 2019.

- 50. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . The Skilled Nursing Facility Value‐Based Purchasing (SNF VBP) Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/Value‐Based‐Programs/SNF‐VBP/SNF‐VBP‐Page.html. Accessed May 24, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Author Matrix

Appendix S1