Abstract

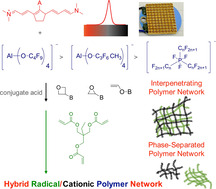

NIR‐sensitized cationic polymerization proceeded with good efficiency, as was demonstrated with epoxides, vinyl ether, and oxetane. A heptacyanine functioned as sensitizer while iodonium salt served as coinitiator. The anion adopts a special function in a series selected from fluorinated phosphates (a: [PF6]−, b: [PF3(C2F5)3]−, c: [PF3(n‐C4F9)3]−), aluminates (d: [Al(O‐t‐C4F9)4]−, e: [Al(O(C3F6)CH3)4]−), and methide [C(O‐SO2CF3)3]− (f). Vinyl ether showed the best cationic polymerization efficiency followed by oxetanes and oxiranes. DFT calculations provided a rough pattern regarding the electrostatic potential of each anion where d showed a better reactivity than e and b. Formation of interpenetrating polymer networks (IPNs) using trimethylpropane triacrylate and epoxides proceeded in the case of NIR‐sensitized polymerization where anion d served as counter ion in the initiator system. No IPN was formed by UV‐LED initiation using the same monomers but thioxanthone/iodonium salt as photoinitiator. Exposure was carried out with new NIR‐LED devices emitting at either 805 or 870 nm.

Keywords: cations, interpenetrating polymer network, near infrared, photopolymerization, weakly coordinating anion

Change of the excitation wavelength enables formation of interpenetrating polymer networks based on radical and cationic photopolymerization where heptamethines and iodonium salts served as initiating system also for photopolymerization of epoxides, oxetanes and vinyl ether. Engineering of the anion marked the tetra(nonafluoro‐t‐butoxy)aluminate as best candidate.

Introduction

New methods on photopolymerization with focus on either radical[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] or cationic mechanism[ 9 , 10 ] have received great interest within the last years.[ 11 , 12 ] The biggest growth on publications has been noticed focusing on radical polymerization where numerous reports appeared considering new approaches related to living radical polymerization[ 3 , 4 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ] applying UV, [16] visible [17] or near‐infrared (NIR)[ 13 , 18 ] radiation following either a RAFT[ 3 , 4 , 19 , 20 , 21 ] or ATRP[ 13 , 14 , 15 , 22 , 23 ] reaction protocol. Remarkable are those studies reporting polymerization under oxygen.[ 6 , 8 , 19 , 21 , 24 ] On the other hand, studies with focus on living cationic mechanisms can be seen more or less as rare although efforts were reported in this field. [25]

Big progress has been noticed regarding the use of new ecologic light sources where high‐intensity LED devices and semiconductor lasers with emission in the NIR fit into this frame.[ 9 , 11 , 26 , 27 ] Demands of the society to work with more resource saving equipment and new regularities with focus to replace older resource‐wasting techniques based on mercury lamps have enforced the development in this direction. [28] NIR‐sensitized photopolymerization was brought into this field by cw‐NIR‐lasers twenty years ago.[ 29 , 30 ] In addition, new directions to employ more efficient drying techniques have also led to the development of lasers with line‐shaped focus whose emission centered at 808 nm and/or 980 nm. [31] This brought a new technique into the field; that is, laser drying using a heat‐sensitive substrate. [31]

Furthermore, up‐conversion nanoparticles with the capability to generate UV‐light showed acceptable performance to initiate free radical polymerization of systems comprising UV initiators applying a 980 nm laser.[ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] Remarkable results achieve deep curing lengths applying free radical polymerization,[ 34 , 36 ] while the first report of an ATRP mechanism based on a metal‐free system appeared in 2017. [33]

There has been increased interest in the use of high‐intensity LEDs for the initiation of photopolymerization.[ 9 , 11 , 26 ] The medical sector, in particular dentistry, has established visible‐light‐based systems for the restauration of teeth many years ago.[ 37 , 38 ] The aforementioned issues regarding the substitution of older excitation techniques based on Hg lamps have driven more activities to develop alternatives such as UV‐LEDs. [11] This has been successful, but issues have arisen for systems which comprise additives with absorption in the UV and visible part. From this point of view, NIR‐LEDs depict an alternative applying an initiator system based on a sensitizer in combination with iodonium salt carrying an anion exhibiting weakly coordinating properties.[ 10 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ] In particular, the bis(trifluoromethyl sulphonyl) imide (NTf2 −) exhibited outstanding performance regarding the compatibility in different acrylate coatings. [43] Regarding the performance, it competed well with the FAP anion (b)[ 44 , 45 ] the applicability of which was protected for a broad range of uses. [46] Later, an iodonium salt comprising an aluminate anion (d) was introduced[ 39 , 42 ] with a special perfluoroalkyl pattern which shielded the coordinating spheres well, which explains the exceptional performance of this anion. [39] These developments were driven by the issue to substitute the widely used PF6 − anion (a). It can release HF under certain circumstances.[ 47 , 48 ]

NIR‐sensitized polymerization worked first only with a neutral NIR absorber carrying a barbiturate group at the meso‐position.[ 43 , 45 , 49 ] Only aziridines polymerized using this sensitizer forming nucleophilic products upon exposure. [50] The first report about successful cationic crosslinking of epoxides appeared in 2019 where a new high‐power NIR‐LED device brought progress in this field. [9] This device helped to overcome the internal activation barrier of cationic NIR sensitizers in combination with iodonium salts.[ 26 , 27 ] A special substitution pattern in the central moiety prevented formation of nucleophilic photoproducts that typically inhibit cationic polymerization of epoxides.[ 9 , 50 ] This brought big progress in this field while comparative investigations with UV‐LED systems using d as anion support these findings. [10] Until today, only aziridines [50] and epoxides[ 9 , 10 ] have served as monomers for cationic photopolymerization. Monomers comprising vinyl ether [51] or oxetane[ 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 ] moieties complement the pattern of cationic crosslinking. Such cationic polymerization studies may be extended to explore the formation of (semi‐)interpenetrating polymer networks applying UV exposure the formation of which can sometimes fail.[ 52 , 53 ] NIR‐sensitized polymerization of hybrid systems based on a radical and cationic mechanism may bring new light in this field because they additionally provide heat generated by internal conversion.[ 11 , 26 ] This might help such systems to step over internal diffusion barriers.

Finally, the search for the “best” anion for the use in photoinduced cationic crosslinking has not reached its final state yet. The exceptional behavior of the anion d [39] as shown in Scheme 3, vide infra, turns out to be a good alternative although its high molecular weight requires higher weight amounts to obtain comparable molar ratios. For this reason, the anion e was developed possessing less fluorine to decrease the molecular weight. Comparison of the results with respect to b, which was believed to be a well‐functioning anion for these purposes, would bring deeper light into this field.[ 44 , 45 , 46 ] Thus, alternative anions such as e and f [44] were applied for additional considerations to drive the reactivity in the desired direction by selection of the appropriate anion.

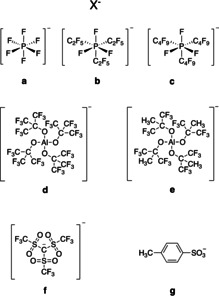

Scheme 3.

Structure of the different anions X− used as counterion for 1, 1′, and 2.

Oxetanes have moved in the focus of photoinduced cationic crosslinking.[ 52 , 53 ] Their material properties have attracted the interest of applications comprising electronic components.[ 57 , 58 ] Further fields in material sciences additionally put the focus on the manufacturing of interpenetrating polymer networks where both radical and cationic crosslinking contribute to build up crosslinked material exhibiting no phase separation between both individually formed crosslinked materials. This typically results in one glass transition temperature and unique material properties complementing each other. Oxetanes also bring the benefit to polymerize via the oxonium ion, [56] which makes them more tolerant against the attack of alcohols or COOH groups. This might bring them to lithographic applications in electronic industry.

Results and Discussion

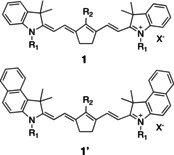

Previous studies showed the successful application of 1 and 1′ for NIR‐sensitized cationic crosslinking, Scheme 1.[ 9 , 11 ] The five‐membered ring pattern in the central point of the polymethine pattern prevents bond cleavage of the polymethine chain,[ 9 , 11 , 26 ] which resulted in the formation of nucleophilic products in the case of six‐membered moieties that typically inhibit cationic polymerization. [49] The pattern of either 1 or 1′ differs with respect to substitution at the (benz)indolium ring and at the meso‐position affecting the compatibility with the surrounding matrix and localization of absorption maximum, respectively. The extension of the conjugated pattern at the indolium moiety from 1 to 1′ resulted in the expected red shift of absorption resulting in easier enabling of 870 nm NIR‐emitters, Table 1, vide infra.

Scheme 1.

Structure of the NIR sensitizers applied for the investigation of reactivity in cationic photopolymerization (Scheme 3 shows the structure of the anion X−).

Table 1.

Summary of NIR sensitizers used and their respective absorption data in M4 a taken at 23 °C, see Figure SI2 for more details.

|

Structure |

Anion |

R1 |

R2 |

λ max (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

a |

n‐C4H9 |

N(Ph)2 |

805 |

|

1 |

d |

n‐C4H9 |

N(Ph)2 |

805 |

|

1 |

g |

n‐C4H9 |

Ph |

799 |

|

1′ |

b |

CH3 |

N(Ph)2 |

849 |

The NIR‐sensitizer transfers an electron from its excited state to an iodonium cation; that is, the diaryl iodonium cation 2, Scheme 2,[ 43 , 49 ] as introduced earlier by a mechanism based on an internal activation barrier.[ 26 , 27 ]

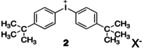

Scheme 2.

Structure of the iodonium cation carrying the respective cation X− (Scheme 3 shows the structure of the anion).

Selection of the anion requests more attention. 1/1′ and 2 carry the anion X−, which can exchange within the different cations (1/1′ and 2) resulting under certain circumstances in precipitation of the ion‐exchanged material. [11] Scheme 3 depicts the anions chosen, which were, except of g, selected from the group of weakly coordinating anions. [40] The latter was included to explore its influence on the overall polymerization efficiency because the sensitizer remained at a low concentration.

Starting point for all investigations was the replacement by alternatives having no environmental and hazardous issues as the HF‐release in the case of a.[ 47 , 48 ] For this reason, the following combinations were chosen to keep such events at a low level: a pair of 1 a/2 a, 1′b/2 b, 1′b/2 c, 1 d/2 d, and 1 d/2 e. These variations enable us to draw the respective conclusions because both 1/1′ and 2 carry either the same anion or an anion of a similar structure.

Table 1 gives an overview about the NIR sensitizers chosen. The motivation to extend the variation by the introduction of c was based on the expectation to improve the performance of b by replacement by c possessing an extended fluorinated alkyl group helping to minimize the interactions between the nucleophilic center of the anion with growing cationic species in cationic polymerization. In addition, the replacement of some CF3 groups in d by CH3 groups resulted in e with the assumption that these small changes should not have a deep impact on cationic polymerization performance. Moreover, the anion f was introduced to extend the grown knowledge in this field (combination 1 a/2 f) while a combination between 1 g and 2 d made it possible to draw conclusions whether this affordable anion g, which exists only in small concentrations in the system, can be seen as an alternative candidate to obtain acceptable reactivities.

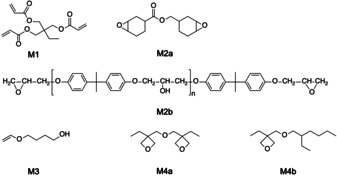

Scheme 4 shows the monomers studied. M1 takes the part of radical polymerization in a hybrid radical/cationic polymerization system. The monomers M2, and M4 a result in cationic crosslinked materials. They may form interpenetrating polymer networks with crosslinked M1 if both form one phase. This can become a problem since some systems may undergo phase separation.[ 59 , 60 ] Radical polymerization proceeds faster than cationic polymerization. [61] This complicates polymer formation according to a cationic mechanism because diffusion of the growing chains through the already formed network by radical polymerization might be significantly slower. Therefore additional activation is required to succeed. NIR sensitizers the deactivation of which mostly proceeds radiationless may provide additional thermal energy to avoid such circumstances. Thus, one may expect better performance to build up in interpenetrating polymer networks using a NIR‐photopolymer system generating conjugate acid [11] to initiate cationic polymerization.

Scheme 4.

Structure of the different monomers used for radical (M1) and cationic (M2–M4) polymerization initiated by NIR exposure applying a photoinitiator system comprising 1/1′ and 2.

Oxetanes were included in this study to compare their polymerization behavior with epoxides. While oxiranes indicate a pronounced influence of conjugate acid on chain growth with less tolerance towards nucleophiles, [62] oxetanes prefer to grow the polymer chain via the oxetanium ion [56] exhibiting more tolerance in the presence of functional groups such as alcohols or carboxylic acid. Some oxetanes comprise these groups even in the monomer unit. It may also explain the increased interest in the use of such monomers for microelectronic applications because processing of materials based on oxetanes appears to proceed with more tolerance compared to epoxides.

Previous investigations showed that the conductivity of the coinitiator, the iodonium salt 2X−, possesses a key function to generate initiating species such as radicals in NIR‐photopolymers. [43] The better the dissociation into the respective ions the higher the reactivity while non‐conducting ion pairs do not contribute to reactivity. Nevertheless, a model quantitatively describing the relation between reactivity and ion dissociation has not yet been developed for systems in which photochemistry occurs in organic surroundings. [43] It has been used as a compromise to explain structure–reactivity relations in different aprotic surroundings. The data in Table 2 show that there exists a rough inverse relation between viscosity and conductivity but a quantitative evaluation of data by the Walden‐Plot [63] failed, which shows the complexity of such systems.

Table 2.

Viscosity data of the monomers used (M2 a, M3, M4 a, M4 b) and selected conductivity data for the respective iodonium salts (2X −) ([2X −]=3.8×10−2 mmol g−1).

|

|

Iodonium salt |

M2 a |

M3 |

M4 a |

M4 b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Viscosity (mPa s) |

|

739 |

4.4 |

12.2 |

3.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

conductivity (S cm2 mol−1) |

2 a |

0.003 |

0.7 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

|

2 b |

|

|

0.28 |

|

|

|

2 c |

|

|

0.08 |

|

|

|

2 d |

|

|

0.61 |

|

|

|

2 e |

|

|

0.11 |

|

|

|

2 f |

|

|

0.29 |

Furthermore, consideration of ion conductivity in the oxetane M4 a indicated discrepancies between ion size and conductivity. Surprisingly, anion a shows the lowest conductivity while larger ions such as d exhibit higher conductivity being related to dissociation degree. Only the dissociated and well solvated ion contributes to conductivity while ion pairs show no conductivity. [43] Higher‐molecular assemblies can exist [43] that may affect conductivity, which explains the discrepancies mentioned above. A slight variation of the anion structure has a deep impact on conductivity supporting this discussion. For example, extension of the fluorinated group in b by just two CF2‐moieties resulting in c indicated a drop of conductivity although the size only slightly changed. A similar behavior was observed by comparison of the ions d and e. Partial replacement of four CF3 groups by four methyl groups showed significant decrease of the conductivity indicating less tendency to form dissociated ions which contribute to reactivity. More theoretical work will be necessary in the future to develop fundamental relations describing the reactivity of such NIR‐photopolymers with respect to their dissociation capability affecting the reaction rate of polymerization.

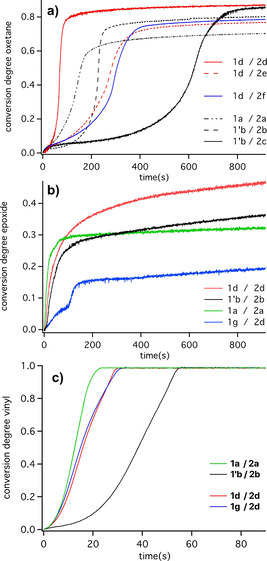

Data obtained in the vinyl monomer M3 complement the scenario as shown in Figure 1. Comparative experiments using the UV photoinitiator TPO‐L, Ethyl(2,4,6‐trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphinate forming radicals [64] to initiate radical polymerization showed no response in the case of M3. Thus, one can expect that this monomer prefers to polymerize according to a cationic mechanism as shown by the data in Figure 1 c. Comparison of the reactivity in M3 with that obtained in case of the epoxide M2 a and oxetane M4 a (Figures 1 a,b) indicates a much faster cationic polymerization in the case of the vinyl ether M3, Figure 1 c. Turning off the light source indicated a reaction of the vinyl group. A chain reaction mechanism occurring in the dark may explain the scenario shown in Figure SI9. This can be based on the formation of nucleophilic radicals originating from M3 resulting in a reaction with the iodonium salt as shown with previously investigated similar systems.[ 65 , 66 ] It may explain the higher reactivity of M3 as well.

Figure 1.

Real‐time FTIR conversion degree–time profiles of NIR‐sensitized photopolymerization at 805 nm investigated for different combinations of sensitzer 1/1′X− and iodonium salt 2X − in different cationic polymerizing monomers. a) M4 a, b) M2 a, c) M3. Intensity of the 805 nm LED device was 1.2 W cm−2 ([Sens]=6×10−3 mmol g−1, [2X−]=3.8×10−2 mmol g−1).

The system comprising the aluminate anion d showed overall the best performance in M4 a while the reactivity was slightly lower compared to a in both M2 a and M3. Surprisingly, systems comprising the FAP anion b exhibited less reactivity compared to those carrying d as anion in the salts. This is surprising since this anion was believed to function as an outstanding candidate for many purposes. [46] However, our results demonstrate an opposite behavior. Even a small change of b resulting in c had a big impact on the reactivity as concluded by comparison of the curves in Figure 1 a although the general pattern of this phosphate does not depict big changes. These differences observed were not as large in Figure 1 b while Figures 1 a and 1c exhibit similar trends. Similar results were also obtained using iodonium salts comprising either the anion d or e. The intention to make a slightly modified anion with lower molecular weight to decrease the loading with non‐polymerizing components resulted in a huge change of reactivity, compare curves obtained in the case of 1 d/2 d and 1 d/2 e.

Furthermore, sensitizer 1 g carrying the more nucleophilic anion g also demonstrates acceptable performance, Figure 1 c. Due to the high extinction coefficient of the heptamethine sensitizer, [11] the concentration of this anion is relatively low and its inhibiting effect on cationic polymerization is rather moderate. Thus, a small concentration of such nucleophilic anions does not strongly interfere with the overall polymerization efficiency as concluded from Figure 1 c. However, Figure 1 b reports the opposite trend.

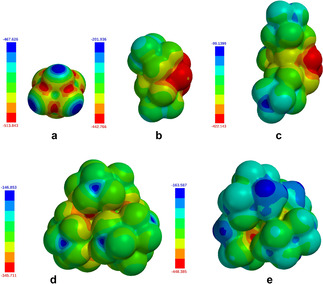

The electrostatic potentials calculated after geometry optimization based on density functional theory (B3LYP functional; 6‐31G*+ level) might give one possible explanation to better understand the observed differences regarding the polymerization efficiency, see Figure 2 depicting the differences in partial charges of each anion. By definition, red color corresponds to negative partial charges while blue color indicates positively charged areas. [67] While all CF3 groups shield the partial negative charges of d well, there is huge difference in comparison with a–c and e which may be related to the reactivity found for the different anions. Thus, the distribution of negative partial charges and therefore nucleophilic points should be as low as possible on the surface. From this point of view the shielding of the CF3‐groups fits well in this pattern as calculated in the case of the anion d. Interestingly, a small change in the structure of d resulting in e had an impact on reactivity as shown below. Thus, shielding of the negative charge appears more efficient in the case of d in comparison with e.

Figure 2.

Electrostatic potential surface of the anions d and e showing the efficient shielding of nucleophilic centers (red) in the anion by the CF3 groups. Calculation results are based on the density functional theory (B3LYP/6‐31G* method). Results obtained regarding the volume and surface are as follows: a: 84 Å3, b: 259 Å3, c: 433 Å3, d: 582 Å3, e: 501 Å3.

These results indicate huge reactivity changes upon changes in small structural features. In general, 2 d turned out to be the best coinitiator for all systems comparing rate of polymerization at the beginning and the final conversion degree. It shows surprisingly better performance than the system based on 2 b, which was believed to be one of the most well performing iodonium coinitiators. [44] 1 d and 2 d worked well in epoxides (M2), vinyl ether (M3), and oxetanes (M4), see the Supporting Information for complementary results. On the other hand, quantification of conjugate acid formed upon NIR exposure showed a concentration of 10−5 m after 5 min exposure in lauryl methacrylate as probed with Rhodamine B lactone [50] (SI discloses more details). Thus, the anion of 1/1′ and 2 causes the huge reactivity differences reported above. A higher value of conjugate acid formation was detected by changing the environment to make it capable of a polymerization according to a radical polymerization mechanism. Lauryl methacrylate (LMA) served as a matrix favoring the formation of the blue photoproduct as previously discussed for other systems. [26]

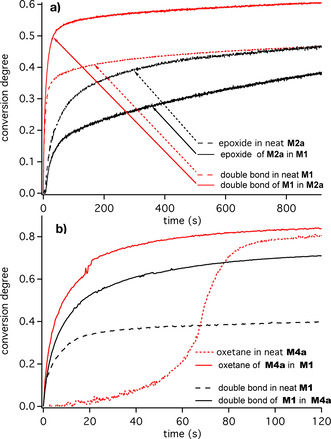

Therefore, the combination 1 d/2 d was preferred for further studies to evaluate hybrid radical/cationic polymerization systems. The conversion degree–time profiles in Figure 3 show a faster radical polymerization of M1 in the presence of the cationic polymerizable monomers M2 a and M4 a. Cationic polymerization proceeds slower than radical polymerization. [61] Thus, the monomer, which is either the epoxide or the oxetane, plasticizes the surrounding typically resulting in a decrease of T g and increase in mobility. It also explains why the epoxide in Figure 3 a polymerizes more slowly in the mixture comprising M1 and M2 a while it reacts fast in neat M2 a. The situation changes in Figure 3 b where the oxetane M4 a polymerizes faster in the system where both radical and cationic crosslinking occur; that is the mixture of M4 a and M1. The different mechanisms of cationic polymerization may explain these findings. Conjugate acid formed initiates polymer formation, whereby in the case of epoxides the growth proceeds via the carbocation more efficiently while an alkylated oxetanium ion serves as intermediate for the chain growth of oxetanes.[ 55 , 56 , 62 ] The heat released by the NIR sensitizer, which is higher than 85 % with respect to all absorbed photons, can thus help to overcome internal activation barriers of chain growth if that process possesses a remarkable internal activation energy. It can lead to a temperature increase above 100 °C (see Figure SI6 for more details) as caused by contribution of non‐radiative deactivation.

Figure 3.

Real‐time FTIR conversion degree–time profiles considering the radical polymerizable acrylate group of M1 with the conversion degree of cationic polymerizable groups comprising the respective epoxide and oxetane monomers M2 a and M4 a, respectively. NIR‐sensitized photopolymerization was pursued at 805 nm investigated by the initiator combination of 1 d and 2 d ([1 d]=6×10−3 mmol g−1, [2 d]=3.8×10−2 mmol g−1). For comparison, polymerization was pursued in the neat monomers M1, M2 a, and M4 a and mixtures of M1/M2 a and M1/M4 a. Intensity of the 805 nm LED device was 1.2 W cm−2.

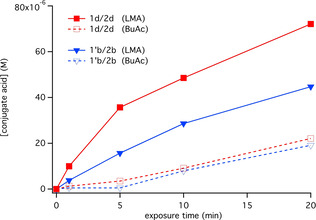

The different surroundings used to pursue the experiments shown in Figure 4 also explain the different reactivities for cationic polymerization shown in Figure 3. The combination comprising 1 d and 2 d generated with better efficiency conjugate acid in comparison with that consisting of 1′b and 2 b. Anion b was developed as an alternative to a and was believed to be the best candidate for a long time.[ 44 , 45 , 46 ] However, the aluminate anion d introduced in 2015 [39] was more efficient compared to b confirming previous results.

Figure 4.

Profiles for formation of conjugated acid as a function of exposure time at 805 nm (Intensity: 1.2 W cm−2) according to a previous procedure [50] using Rhodamine B lactone to quantitatively probe the amount of acidic species. Measurements were carried out in lauryl methacrylate (LMA) and butyl acetate (BuAc) ([Sens]=4.1×10−5 M, [2X−]=5.6×10−4 M).

Change of the environment by a monomer carrying a radical polymerizable vinyl group resulted in an increase in the efficiency of conjugate acid formation although also in this system the combination comprising d showed better performance compared to those with b. Obviously, the vinyl group possesses a key function here, see also Supporting Information of ref. [9]. Photoexcited oxidation of the NIR sensitizer Sens by the iodonium cation results in formation of Sens +⋅. Sensitizers comprising a trimethylene bridge in the center of the molecule typically cleave at the polymethine chain while those with dimethylene moieties oxidize resulting in formation of a connecting double bond with no bond cleavage in the polymethine chain and therefore no formation of nucleophilic products.[ 9 , 26 ] This can explain the higher rate of conjugate acid formation in the case of systems comprising lauryl methacrylate as model monomer with no capability to form crosslinked material during the experiment in Figure 4. These findings also help to explain the higher polymerization efficiency of the oxetane group in the mixture of M1 and M4 a. Experiments in epoxides cannot confirm these findings. The reaction proceeds more slowly in such systems while cationic polymerization is based on carbocations as intermediates. On the other hand, conjugate acid favors a protonation of the oxetane group resulting in formation of oxetanium as intermediate in cationic polymerization. [56] Obviously, the higher concentration of conjugate acid consequently promotes a higher oxetanium concentration resulting in a significant increase in polymerization rate.

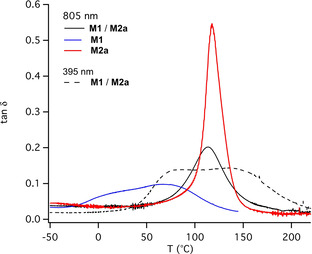

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) of the networks made by both UV‐ and NIR‐sensitized polymerization showed different properties (see Figure 5 and Table 3). A previously applied photoinitiator system comprising isopropyl thioxanthone (ITX) and the respective iodonium salt generated conjugate acid upon exposure with a UV‐LED emitting at 395 nm. [10] The maximum of the tanδ curve signalizes the glass transition temperature of the film obtained. It depicts one glass transition temperature appearing at 113 °C for the NIR‐system comprising 1 d/2 d while two maxima where obtained in the case of UV‐initiated radical polymerization applying the same monomer mixture. The peak at 86 °C corresponds to the radical polymerizable monomer M1 while the second peak appearing at 134 °C is related to the epoxide M2 a. The neat crosslinked materials M1 and M2 a exhibit peak maxima at 67 °C and 119 °C, respectively, demonstrating the formation of two phases in the mixture after being exposed to UV radiation. This indicates a phase separation during polymerization taking a typical UV initiation system and no interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) formation while NIR‐sensitized radical and cationic polymerization promotes the formation of IPNs as firstly shown in this experiment. In addition, M1 itself formed a polymer, which broke during the experiment at 140–150 °C.

Figure 5.

DMA data (tanδ) of films (thickness: 120 μm) exposed at 395 nm (1.1 W cm−2) and 805 nm (1.2 W cm−2) in the case of the monomers M1 and M2 a after 2 min and 10 min exposure at 395 nm (1.1 W cm−2) and 805 nm (1.2 W cm−2), respectively. ITX (0.1 wt %) and 2 d (3.8×10−2 mmol g−1) and the combination of 1 d (6.0×10−3 mmol g−1) and 2 d (3.8×10−2 mmol g−1) served as initiator combination for experiments at 395 nm and 805 nm, respectively.

Table 3.

Summary of DMA data (T g: glass transition temperature determined from the maximum of tanδ, E′: storage modulus obtained 40 K above T g where the system can be seen as relaxed) obtained after exposure of 2 min at 395 nm and 10 min at 805 nm with a radiation source emitting either 395 nm (1.1 W cm−2) or 805 nm (1.2 W cm−2) while the conversion degree at this time x ∞ was determined for the monomer polymerizing according to a cationic polymerization mechanism (cat) and/or radical polymerization mechanism. Thickness of the films was 120 μm.

|

Monomer (wt %) |

|

805 nm exposure |

|

395 nm exposure |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M1 |

M2 a |

M2 b |

M4 a |

|

x ∞ (cat) |

x ∞(rad) |

tanδ max |

T g (°C) |

E′ (MPa) |

|

x ∞ (cat) |

x ∞ (rad) |

tanδ max |

T g (°C) |

E′ (MPa) |

|

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

– |

0.51 |

0.099 |

67 |

[a] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

0.96 |

– |

0.55 |

119 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

0 |

100 |

|

|

0.75 |

– |

0.32 |

139 |

57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

|

0.91 |

– |

0.067 0.030 |

77 194 |

[b] |

|

0.96 |

– |

0.084 |

96 175 |

|

|

50 |

50 |

0 |

0 |

|

0.81 |

0.75 |

0.20 |

113 |

63 |

|

0.89 |

0.90 |

0.13 0.14 |

86 134 |

60 |

|

50 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

|

0.78 |

0.47 |

0.23 |

103 |

178 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

0.60 |

0.69 |

0.048 |

91 177 |

[b] |

|

0.95 |

0.86 |

0.059 |

91 154 183 |

[b] |

|

40 |

30 |

0 |

30 |

|

0.67/0.75 |

0.75 |

0.079 |

131

|

[b] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

0 |

30 |

30 |

|

0.81/0.52 |

0.67 |

0.093 |

131 220 |

[b] |

||||||

[a] Film broke, no data available. [b] Curve was not fully relaxed.

One can still assume that the heat generated by the NIR sensitizer possesses a key function to explain why IPN formation succeeded while it failed in the case of UV excitation. The much faster polymerization in the case of the cationic polymerizable monomer in the NIR system supports these findings. This might also help to overcome internal activation energies in the polymerization process, because the temperature generated can exceed 100 °C (see Figure SI6 in SI).

Table 3 shows the data obtained for systems comprising different monomers and mixtures applied for polymerization. It also includes the storage modulus for systems relaxed at least 40 K above the detected glass transition. This quantity is roughly related to the network density. This was applicable to some systems comprising epoxides. However, oxetanes failed in such considerations because they exhibited a second transition (see Figure SI7 and SI8 in SI). It presumably relates also to a glass transition of a domain with less mobility caused in a partially phase separated system as previously also reported for an oxetane/acrylate system cured by UV exposure.[ 52 , 53 ] It does not relate to melting as concluded by the shape of the storage modulus in this temperature region (See Figure SI8). Thus, the system still responded upon heating up to 250 °C. Since this temperature appeared quite high, it was dispensed to continue the experiment at temperatures >250 °C because data obtained would not reliably describe mechanical relaxation of this system due to possible thermal damage. Nevertheless, our experiments confirm findings obtained by UV exposure that curing of oxetanes results in tanδ curves showing more than one peak.[ 52 , 53 , 68 ]

Conclusion

NIR‐sensitized photopolymerization comprising a sensitizer with bridged pattern to avoid bond cleavage of the polymethine chain, and therefore formation of nucleophilic products in combination with an iodonium salt, showed good performance upon exposure to a high‐intensity NIR LED emitting at 805 nm; that is in general a structural pattern comprising either an indolium or benzo[e]indolium pattern. Furthermore, an anion with optimal shielding of nucleophilic moieties of the anion and large anion radius showed the best performance as observed by real‐time FTIR spectroscopy. This will give new impetus to design similar systems in the future showing that the anion adopts a special function. Moreover, the heat generated by the NIR sensitizer makes such systems interesting for future developments in material research since UV‐LED based initiation failed to form interpenetrating polymer network.

The heat generated by non‐radiative processes has a special function in such NIR systems since it enabled the formation of interpenetrating polymer networks while UV exposure led to the expected phase separation between the crosslinked acrylate and epoxide. Nevertheless, a switch to oxetanes showed no clear formation of IPN. Thus, phase separation still controls the morphology and therefore the mechanical properties of such systems as well.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

BS and YP acknowledge the Project D‐NL‐HIT carried out in the framework of the INTERREG‐Program Deutschland‐Nederland, which is co‐financed by the European Union, the MWIDE NRW, the Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat and the provinces of Limburg, Gelderland, Noord‐Brabant und Overijssel. BS additionally thank the county of North Rhine‐Westphalia for funding of the project REFUBELAS (grant 005‐1703‐0006). We additionally thank the BMWi for funding the Project Innovative Nano‐Coatings for financial support of research at Niederrhein University of Applied Sciences ((ZIM cooperation project (ZF4288703WZ7) and FEW Chemicals GmbH (ZIM cooperation project (ZF4288702WZ7)) financial support. We also thank Phoseon and EASYTEC for providing the high intensity NIR‐LED devices emitting at 805 nm and 870 nm, respectively. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Y. Pang, A. Shiraishi, D. Keil, S. Popov, V. Strehmel, H. Jiao, J. S. Gutmann, Y. Zou, B. Strehmel, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1465.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Yingquan Zou, Email: zouyq@bnu.edu.cn.

Prof. Dr. Bernd Strehmel, Email: bernd.strehmel@hsnr.de.

References

- 1. Wu Z., Jung K., Boyer C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2013–2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 2029–2033. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Discekici E. H., Anastasaki A., Read de Alaniz J., Hawker C. J., Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7421–7434. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Z., Corrigan N., Bagheri A., Jin J., Boyer C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17954–17963; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 18122–18131. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yeow J., Chapman R., Gormley A. J., Boyer C., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4357–4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dadashi-Silab S., Doran S., Yagci Y., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10212–10275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enciso A. E., Fu L., Russell A. J., Matyjaszewski K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 933–936; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 945–948. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mokbel H., Anderson D., Plenderleith R., Dietlin C., Morlet-Savary F., Dumur F., Gigmes D., Fouassier J. P., Lalevee J., Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 132, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonardi A. H., Dumur F., Grant T. M., Noirbent G., Gigmes D., Lessard B. H., Fouassier J. P., Lalevee J., Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmitz C., Pang Y., Gülz A., Gläser M., Horst J., Jäger M., Strehmel B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4400–4404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 4445–4450. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kocaarslan A., Kütahya C., Keil D., Yagci Y., Strehmel B., ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strehmel B., Schmitz C., Kütahya C., Pang Y., Drewitz A., Mustroph H., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 415–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmitz C., Oprych D., Kutahya C., Strehmel B., in Photopolymerisation Initiating Systems (Eds.: Lalevée J., Fouassier J.-P.), Royal Society of Chemistry, London, 2018, pp. 431–478. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kütahya C., Schmitz C., Strehmel V., Yagci Y., Strehmel B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7898–7902; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 8025–8030. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kütahya C., Meckbach N., Strehmel V., Gutmann J. S., Strehmel B., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 10444–10451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corrigan N., Xu J., Boyer C., Macromolecules 2016, 49, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tasdelen M. A., Uygun M., Yagci Y., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kütahya C., Wang P., Li S., Liu S., Li J., Chen Z., Strehmel B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3166–3171; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 3192–3197. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shanmugam S., Xu J., Boyer C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1036–1040; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang L., Wu C., Jung K., Ng Y. H., Boyer C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16811–16814; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 16967–16970. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corrigan N., Yeow J., Judzewitsch P., Xu J., Boyer C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5170–5189; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 5224–5243. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gormley A. J., Yeow J., Ng G., Conway Ó., Boyer C., Chapman R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1557–1562; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ribelli T. G., Konkolewicz D., Bernhard S., Matyjaszewski K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13303–13312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ribelli T. G., Konkolewicz D., Pan X., Matyjaszewski K., Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6316–6321. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corrigan N., Rosli D., Jones J. W. J., Xu J., Boyer C., Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6779–6789. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ciftci M., Yoshikawa Y., Yagci Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 519–523; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 534–538. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pang Y., Fan S., Wang Q., Oprych D., Feilen A., Reiner K., Keil D., Slominsky Y. L., Popov S., Zou Y., Strehmel B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11440–11447; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 11537–11544. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strehmel B., Schmitz C., Cremanns K., Göttert J., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 12855–12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmitz C., Strehmel B., Eur. Coat. J. 2018, 124, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baumann H., Hoffmann-Walbeck T., Wenning W., Lehmann H.-J., Simpson C. D., Mustroph H., Stebani U., Telser T., Weichmann A., Studenroth R., in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2015, pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baumann H., Chem. Unserer Zeit 2015, 49, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strehmel B., Brömme T., Schmitz C., Reiner K., Ernst S., Keil D., in Dyes and Chromophores in Polymer Science, Wiley, Hoboken, 2015, pp. 213–249. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oprych D., Schmitz C., Ley C., Allonas X., Ermilov E., Erdmann R., Strehmel B., ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen Z., Oprych D., Xie C., Kutahya C., Wu S., Strehmel B., ChemPhotoChem 2017, 1, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhu J., Zhang Q., Yang T., Liu Y., Liu R., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Z., Zou X., Shi F., Liu R., Yagci Y., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu R., Chen H., Li Z., Shi F., Liu X., Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 2457–2463. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meereis C. T. W., Leal F. B., Ogliari F. A., Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rueggeberg F. A., Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klikovits N., Knaack P., Bomze D., Krossing I., Liska R., Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 4414–4421. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krossing I., Raabe I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2066–2090; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 2116–2142. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riddlestone I. M., Kraft A., Schaefer J., Krossing I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13982–14024; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 14178–14221. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shiraishi A. (San-Apro Ltd.), JP2019090988, 2019.

- 43. Brömme T., Oprych D., Horst J., Pinto P. S., Strehmel B., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 69915–69924. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shiraishi A., Kimura H., Oprych D., Schmitz C., Strehmel B., J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2017, 30, 633–638. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shiraishi A., Ueda Y., Schlapfer M., Schmitz C., Bromme T., Oprych D., Strehmel B., J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2016, 29, 609–615. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vygodskii Y. S., Sapozhnikov D. A., Shaplov A. S., Lozinskaya E. I., Ignat′ev N. V., Schulte M., Vlasov P. S., Malyshkina I. A., Polym. J. 2011, 43, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sowmiah S., Srinivasadesikan V., Tseng M.-C., Chu Y.-H., Molecules 2009, 14, 3780–3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tseng M.-C., Liang Y.-M., Chu Y.-H., Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 6131–6136. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brömme T., Schmitz C., Moszner N., Burtscher P., Strehmel N., Strehmel B., ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schmitz C., Halbhuber A., Keil D., Strehmel B., Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 100, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tripathy R., Crivello J. V., Faust R., J. Polym. Sci. Part A J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hasa E., Stansbury J. W., Guymon C. A., Polymer 2020, 202, 122699. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hasa E., Scholte J. P., Jessop J. L. P., Stansbury J. W., Guymon C. A., Macromolecules 2019, 52, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deng Y. F., Zou Y. Q., Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 143, 105608 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.105608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Crivello J. V., Bulut U., Des. Monomers Polym. 2005, 8, 517–531. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bulut U., Crivello J. V., J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2005, 43, 3205–3220. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Feser S., Meerholz K., Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 5001–5005. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zacharias P., Gather M. C., Koehnen A., Rehmann N., Meerholz K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4038–4041; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 4098–4101. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fouassier J. P., Lalevee J., Polymers 2014, 6, 2588–2610. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sperling L. H., Interpenetrating Polymer Networks in Adv. Chem. Ser., Vol. 239 (Eds. L. H. Sperling D. Klempner,, L. A. Utracki), American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C., 1994, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Odian G., Principles of Polymerization, Wiley, Hoboken, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bulut U., Crivello J. V., Macromolecules 2005, 38, 3584–3595. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Austen Angell C., Ansari Y., Zhao Z., Faraday Discuss. 2012, 154, 9–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kolczak U., Rist G., Dietliker K., Wirz J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6477–6489. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baumann H., Timpe H. J., Acta Polym. 1986, 37, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Timpe H. J., Rajendran A. G., Eur. Polym. J. 1991, 27, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 67.W. Hehre, S. Ohlinger, Spartan′16, Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, 2016.

- 68. Zheng K., Zhu X., Qian X., Li J., Yang J., Nie J., Polym. Int. 2016, 65, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary