Abstract

Introduction

Caring for people with cognitive problems can have an impact on informal caregivers’ health and well-being, and especially increases pressure on healthcare systems due to an increasing ageing society. In response to a higher demand of informal care, evidence suggests that timely support for informal caregivers is essential. The New York University Caregiver Intervention (NYUCI) has proven consistent effectiveness and high adaptability over 30 years. This study has three main objectives: to develop and evaluate the Flemish adaptation of the NYUCI in the context of caregiving for older people with early cognitive decline; to explore the causal mechanism of changes in caregivers’ health and well-being and to evaluate the validity and feasibility of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment in Flanders.

Methods and analysis

Guided by Medical Research Council framework, this study covers the development and evaluation phases of the adapted NYUCI, named PROACTIVE—suPpoRting infOrmal cAregivers of older people with early CogniTIVe declinE. In the development phase, we will identify the evidence base and prominent theory, and develop the PROACTIVE intervention in the Flemish context. In the evaluation phase, we will evaluate the PROACTIVE intervention with a pretest and posttest design in 1 year. Quantitative data will be collected with the BelRAI Screener, the BelRAI Social Supplement and the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment at baseline and follow-up points (at 4, 8 and 12 months). Qualitative data will be collected using counselling logs, evaluation forms and focus groups. Quantitative data and qualitative data will be analysed with SAS 9.4 software and NVivo software, respectively. Efficacy and process evaluation of the intervention will be performed.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of KU Leuven with a dossier number G-2020-1771-R2(MAR). Findings will be disseminated through community information sessions, peer-reviewed publications and national and international conference presentations.

Keywords: old age psychiatry, psychosocial intervention, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate the Flemish adaptation of the New York University Caregiver Intervention following the Medical Research Council framework.

This study addresses a suPpoRting infOrmal cAregivers of older people with early CogniTIVe declinE(PROACTIVE) intervention specifically working for an unrecognised but critical subpopulation, informal caregivers of older people with early-onset dementia or cognitive problems.

This interdisciplinary study can systematically investigate the efficacy of the PROACTIVE intervention using the combination of instruments developed from the interRAI assessment systems.

The sample of participants might not be entirely representative of the whole population in Flanders and 1-year intervention period may be relatively short.

Introduction

According to data from World Population Prospects, by 2050, one in six persons in the world and one in four persons living in Europe, will be aged 65 or older. The number of persons aged 80 years or over is projected to triple from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050.1 These demographic changes put increasing pressure on healthcare resources. Dementia affects not only older people but also their informal caregivers. Literature shows that compared with other informal caregivers, people caring for persons with cognitive problems are more likely to be greatly impacted, as the caregiving is perceived to be more demanding.2–6 Informal caregivers of people with early cognitive decline can experience a decline in health and quality of life because they have difficulties adapting to the caregiving role and acquiring caregiving coping skills.7 8 A recent scoping review suggested that informal caregivers were more vulnerable when transitioning into the caregiver role, and experienced psychological distress and family conflicts.9 A globally recognised solution to this problem is ‘Healthy Ageing’ proposed by WHO, which can contribute to a sustainable healthcare system. Healthy Ageing is mostly defined ‘as the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.’10

All nations that wish to achieve sustainable development in their healthcare systems, face a similar problem. In Belgium, Flanders in transition 202511 states that sustainable healthcare should be achieved with financial viability as the ageing population will put more pressure on healthcare resources. A formal diagnosis of dementia, in Flanders, usually comes 3–4 years after the first signs of cognitive problems and about 70% of people with diagnosed dementia are cared for by informal caregivers at home.12 Focusing on informal caregiver research, especially informal caregivers of older people with early-stage or probable dementia, shows to be important in a healthcare system.13 However, little support is provided to this particular group, except for some basic guidance and information (eg, www.dementie.be) or by very local projects (eg, Foton, in Bruges). In addition, there is no systematic needs assessment tool and support plan for informal caregivers in Flanders.14

Well-established evidence is in favour of providing timely intervention for early-phase informal caregivers. Evidence showed that it is necessary to develop and validate psychosocial interventions focusing specifically on the earlier phases of dementia, when both people with dementia and their families have to adjust to the changing disease conditions.15 Caregiver’s burden varies in different stages of frail older people’s impairment and providing early intervention for supporting informal caregivers is important.16 One study showed that providing early support for informal caregivers may contribute to better adaptations to the caregiver’s role and reduce caregiver’s distress.17 A Canadian psychoeducational individual programme for informal caregivers and a booster session on supporting caregiving transition proved to be effective.18 19 In this psychoeducational programme, people in the experimental group were more confident and well prepared for care adjustment and future plan.18 19

Timely support interventions for early-phase informal caregivers of people with cognitive problems are scarce, although many studies evaluated a wide range of interventions to support informal caregivers. A recently performed systematic review found that only a few studies evaluated psychosocial interventions specifically focusing on informal caregivers of people with mild dementia or early cognitive problems.20 21 Reviews of psychosocial interventions for supporting informal caregivers concluded that multicomponent interventions with tailored support to caregivers’ needs are of great success.22 23 Our review also found that the New York University Caregiver Intervention (NYUCI), a multicomponent psychosocial intervention for informal caregivers of people with all stages of dementia, had proven great efficacy and can play a preventive role in supporting informal caregivers.24

In Belgium, perceived greater social support from family and friends is related to lower informal caregiver burden.25 In this perspective, the NYUCI, with its unique emphasis on the maximisation of social support for informal caregivers could also work well in the Flemish context. Therefore, we will develop a Flemish adaptation of the NYUCI for the target group of informal caregivers of older people with early cognitive decline. The Flemish NYUCI, which is named suPpoRting infOrmal cAregivers of older people with early CogniTIVe declinE (PROACTIVE), is the first adaptation of the NYUCI to be conducted in the context of caregiving for relatives with early cognitive decline.

This research will promote health and well-being for informal caregivers and care recipients who are at risk of adverse outcomes by leveraging the power of social support. The aims of the research are:

To develop the PROACTIVE intervention in the Flemish context.

To evaluate the efficacy of the PROACTIVE intervention in Flanders.

To delineate the causal mechanism of health and well-being in early-phase informal caregivers.

To clarify the potential causal mechanism of the PROACTIVE intervention under the conditions of high and low success.

To evaluate the usefulness, feasibility and validity of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment in Flanders.

To achieve the research aims, the following research questions will be answered:

Q1: What is the evidence on psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of older people with early cognitive decline?

Q2: Which factors affect the health and well-being of early-phase informal caregivers and how?

Q3: Process evaluation: What is the potential causal mechanism of the PROACTIVE intervention?

Q4: Does the PROACTIVE intervention enhance the health and well-being of informal caregivers (and care recipients)?

Q5: Is the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment useful, feasible and validated in Flanders?

In this research, we hypothesise that the PROACTIVE intervention will be well developed in Flanders and will show efficacy on maintaining positive health and well-being outcomes (Healthy Ageing). To be specific, informal caregivers receiving support from the PROACTIVE intervention will most likely present improved outcomes, such as better relationship with care recipients and others, less or stable psychological health and enhanced well-being. Meanwhile, care recipients from the PROACTIVE group will show some ameliorations in their symptoms (eg, wandering, expression problems) as caregivers and caregiving can influence care recipients.26 We also hypothesise that the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment will be useful and validated for informal caregivers of people with early cognitive decline in Flanders. Moreover, the potential benefit pathway of action of the PROACTIVE intervention will be clarified to better understand, which intervention elements are more amendable and effective.

Methods and analysis

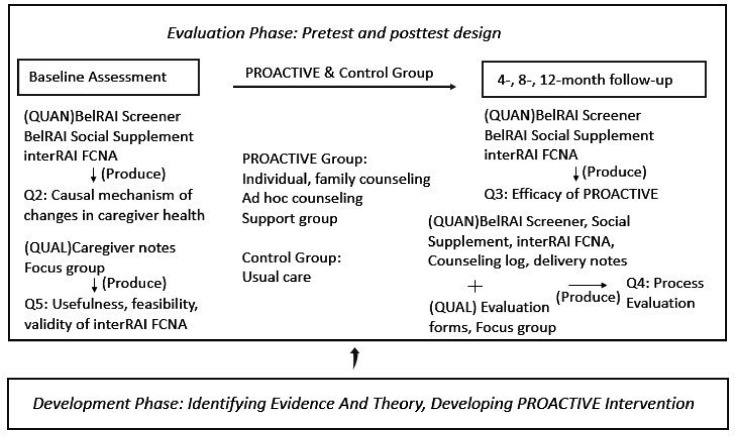

The PROACTIVE Programme is structured following the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework27 for development and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Figure 1 provides a diagram of the study design based on MRC framework.

Figure 1.

Study design based on Medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. PROACTIVE: suPpoRting infOrmal cAregivers of older people with early CogniTIVe declinE, interRAI FCNA: interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment, QUAL: qualitative analysis, QUAN: quantitative analysis.

Development phase

In this phase, we will develop the PROACTIVE intervention based on the adaptation of the NYUCI to the Flemish context.

Research question 1—What is the evidence on psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of older people with early cognitive decline?

A systematic review was performed to identify the appropriate and effective psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of older people with early cognitive decline. We found that the New York University Caregiver Intervention (NYUCI), among a few multicomponent interventions, has proven great efficacy and sustained benefits, including enhanced social support, reduced depressive symptoms, self-rated health, as well as greater positive appraisal of stressors.28–30 The intervention also resulted in large healthcare cost savings over 30 years.31–33 Additionally, the NYUCI proved high adaptability and transferability. Some adaptations of the NYUCI have been implemented in other areas in the USA,34–37 as well as in Australia, England38 and Israel39 40 and similar and positive outcomes were replicated in other scientific studies.

The NYUCI consists of two individual and four family counselling sessions, encouragement of participation in a weekly support group and ongoing telephone-based availability of counsellors to caregivers and families (called ad hoc counselling). Beyond basic counselling, counsellors also provide resource information and referrals for auxiliary help, financial planning, and education for caregivers and family members.24 Underpinning the NYUCI components, it is the stress process theory which has evolved steadily since 1981 and showed great power in caregiver stress research. The main concepts of this theory are: social and economic statuses; primary and secondary stressors; psychosocial resources and health outcomes.41–43 Pearlin et al41 conceived that the demands of caregiving, as encompassing primary stressors (ie, cognitive status, problematic behaviour, activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental ADL (IADL) dependencies), could in turn lead to secondary stressors (ie, family conflict, economic problems) and the emotional distress is likely to appear first in the stress process. Then eventually the physical health conditions will worsen. Moreover, the outcomes should cover mental and physical health of caregivers, their well-being and the sustainability of being a caregiver role. Together, this caregiver stress process theory shows how a mix of circumstances, stressors and resources (ie, coping, social support, appraisal) variably impact caregiver’s health and well-being.

The original NYUCI includes six counselling sessions, and one NYUCI adaptation project in Minnesota defined the completion of intervention as ‘participation in two-thirds or more of the programme sessions.’34 In Flanders, we will reduce the total number of sessions and demands placed on participating informal caregivers in order to avoid fatigue and dropping outs. Basically, the adapted NYUCI called PROACTIVE will consist of wo individual and two family counselling sessions, at least monthly support group participation, and the ongoing availability of counsellors to caregivers and families (called ad hoc counselling). Then, in order to develop a successful Flemish adaption of the NYUCI, namely PROAVTIVE intervention, we will continue the following adaptation work: First, we will match the relevant theory from the stress process model with the intervention elements of the NYUCI. The stress process model shows how stressors have an impact on caregiver’s health and well-being. We will examine each element (ie, individual, family counselling, support group, ad hoc counselling) of the NYUCI and explore their rationale and functions based on the corresponding parts of the stress process theory. Second, materials including programme manual,44 implementation tools, worksheets, counselling summary forms and participant evaluation forms will be rigorously translated from English into Flemish/Dutch. Moreover, training and certification of counsellors will be made via an online video-based programme (http://www.hcinteractive.com/nyuci). Beyond the translation work, we will do the adaptation to (and thus the sociological study of) the cultural particularities of the Flemish healthcare system, care organisations, values and norms about informal care, as well as cultural views on dementia. The adaptation process of the intervention will follow a participatory approach, working with local stakeholders, including informal caregivers, counsellors, local organisations and policy-makers. Moreover, international research networks (ie, Mittelman's research team, LUCAS and interDEM) and stakeholder meetings (ie, care recipients and their caregivers, counsellors, local organisations) will be motivated to ensure the success of the PROACTIVE development.

Evaluation phase

We will answer research question 2–5 during the evaluation phase with a pretest and posttest design in 1 year. Allocation will be concealed from participants and counsellors until after the baseline assessment, and it will be revealed as the counsellors open a sealed envelope in the caregivers’ presence, allocating them to treatment or usual care conditions (control).

Caregivers assigned to the PROACTIVE group will receive the intervention over the course of 1 year. This intervention consists of a time-limited (within 4 months) counselling phase and an ongoing maintenance and support phase, namely ad hoc counselling and support group participation. The counselling sessions will motivate the participants to continue in the process and provide the basis for their ongoing support for each other.

Caregivers assigned to the usual care group will only receive services routinely provided to care recipients and their family, such as resource information and help on request, but they do not participate in the formal counselling sessions or in the support groups. These caregivers will not have any contact with the counsellors.

Instruments

Multiple instruments will be used in this research, including the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment, the BelRAI Screener, the BelRAI Social Supplement, evaluation forms for intervention elements and counselling logs.

The interRAI family carer needs assessment

The interRAI instruments are a suite of internationally standardised, validated assessment tools (http://www.interrai.org). The interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment, as part of the interRAI integrated suite of assessment tools, was developed and tested in a longitudinal study across 11 countries in 2017.45 The Family Carer Needs Assessment is a self-reported assessment, comprising many scale sections, including the role of the family carer, a carer health check, the required level of support, levels of care provided, caring effects on carers, social needs and life quality. This carer needs assessment tool can help identify carer needs and caregiving impact on carers, provide carer with support and advice, and identify caregiving difficulties.

The belrai screener

The BelRAI is an adapted version of the interRAI instruments in Belgium. These instruments are filled out in a secure web application, with an embedded BelRAIWiki site with an online manual.46 A 7-year evaluation project for Belgian home care interventions called protocol 3 showed evidence that the interRAI Home Care (interRAI HC) is a valid instrument to be used in the community setting.47 The BelRAI Screener was developed to be used in the Belgian home care setting consisting of four short modules from the interRAI HC, and one module from the interRAI Mental Health instrument. This short screening instrument determines whether a person should have a full interRAI HC assessment based on a certain cut-off value and is a tool for eligibility of home care services.

The BelRAI social supplement

The BelRAI Social Supplement is a complementary tool for the BelRAI Screener. This tool can assess the social context variables of people living at home, including social engagement, social relationship, feelings of loneliness, communication and mood. Currently, the interRAI assessment instruments (BelRAI) are being mandatorily implemented in the daily care routine in Flanders.

Counselling log and evaluation form for intervention elements will be translated from the NYUCI original materials. Counselling log can collect data about the frequency and type of counselling, as well as frequency of support group participation. There are three types of evaluation forms: evaluation form for individual counselling, family counselling and support group. Each evaluation form includes review questions on whether the intervention element is helpful.

Target population

In this research, early cognitive decline means the early onset of dementia or early cognitive problems (eg, memory loss). Older people with early cognitive decline will be screened through the interRAI Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS2)48 49 embedded in the BelRAI Screener. Older people must be at least 65 years old, live in the community and have a score of 1, 2 or 3 in the CPS2 scale (range 0–8). Participants are the informal caregivers of these older people with early cognitive decline and they are eligible if they (1) are recognised as the primary caregiver, (2) and if they are willing and able to participate. Caregivers may be spouses, children or other family members, either or not living with the care recipient. Caregivers are not eligible if they (1) have already received formal counselling or joined a peer-support group and (2) have insufficient cognitive capacity to complete the intervention.

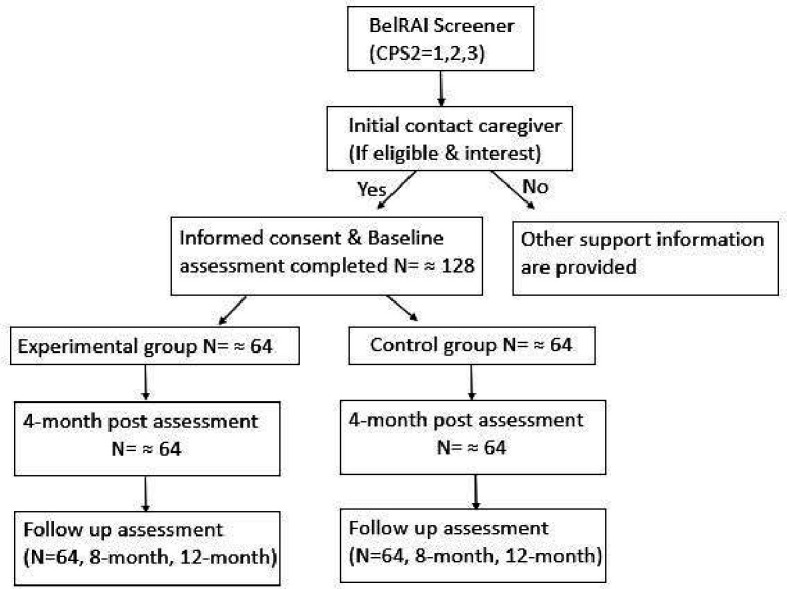

Sample size

The minimum sample size for this research is 128 participants, calculated using GPower software with an effect size of 0.5, a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8.

Recruitment

The following strategies for recruitment of participants will be used: contacting home care organisations, advertisement at community events and marketing to local agencies working with caregivers. The BelRAI Screener instrument will be used to initially screen older people with early cognitive decline (CPS2=1, 2 or 3) and then identify their primary caregivers who are eligible to participate in the intervention and are interested in enrolling. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants, including each caregiver, as well as from any other relatives who come to the family counselling sessions. Figure 2 provides a diagram of planned flow of participants throughout the PROACTIVE study. The Ethics Committee of KU Leuven has approved this protocol with dossier number G-2020-1771-R2(MAR).

Figure 2.

Planned flow of participants throughout the PROACTIVE study CPS2: interRAI Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS2) embedded in the Belrai Screener. PROACTIVE: suPpoRting infOrmal cAregivers of older people with early CogniTIVe declinE.

The PROACTIVE intervention consists of:

Two individual and two family counselling sessions.

At least monthly support group participation.

Ongoing availability of counsellors to caregivers and families (called ad hoc counselling).

Outcomes

The causal mechanism of factors affecting informal caregiver health and well-being.

The effectiveness of the PROACTIVE intervention on the health and well-being of informal caregivers (and care recipients).

The benefit pathway of the action of the PROACTIVE intervention.

The usefulness, feasibility and validity of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment in Flanders.

Data collection and analysis

Research question 2—Which factors affect the health and well-being of informal caregivers and how?

We will use stress process model to explain causal mechanism related to changes in caregivers’ health and well-being. Stressors dataset will be collected using the BelRAI Screener instrument, resources variables and health outcomes dataset will be collected using the BelRAI Social Supplement and the interRAI Carer Needs Assessment in 4-month point.

Regarding the analysis of causal mechanism of direct, mediated and moderated effects, we will use hierarchical regression analyses to explore the associations among resource variables (age, gender, marital status, relationship to the care recipient, appraisals, coping responses, social engagement and relationship with others) and stressors (ADL, IADL, cognition status, behaviour problems) and health outcomes (mental health, life quality, self-rated health). Collected data will be analysed with SAS 9.4 software.

Research question 3—Process evaluation: What is the potential causal mechanism of the PROACTIVE intervention?

The process evaluation of the PROACTIVE intervention guided by MRC guidance,50 aims to delineate the causal mechanism of the intervention under conditions of high and low success, identifying which intervention elements may be most appropriate and amenable for subsequent translation and implementation. In-depth qualitative data on deemed beneficial intervention elements will be collected by means of focus group discussions and delivery notes. Quantitative data on key process variables (frequency and types of counselling contacts, frequency of counselling contacts) will be collected with counselling log and list, as well as evaluation forms. Quantitative data on stressors and caregiver health outcomes will be collected with the BelRAI Screener, BelRAI Social Supplement and interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment at baseline and at 4-month, 8-month and 12-month follow-up.

Qualitative data analysis will be conducted using the NVivo software. A thematic analysis will also be performed. Quantitative data will be analysed with SAS 9.4 software. We will integrate quantitative and qualitative analyses in a mixed-methods approach to clarify the causal pathway of the intervention.

Research question 4—Does the PROACTIVE intervention enhance the health and well-being of informal caregivers (and care recipients)?

Four time point (baseline, 4, 8, 12 months) quantitative data will be repeatedly collected using the BelRAI Screener instrument, the BelRAI Social Supplement and the interRAI Carer Needs Assessment. The specific health and well-being outcomes in informal caregivers will be: (1) IADL, health condition and cognition, and (2) life quality, self-rated health, mental health (depression, stress, anxiety) and (3) relationship with care recipients and others, social engagement and (4) appraisal of caregiving and support needs. The specific health and well-being outcomes in care recipients will be: ADL, IADL, behavioural problems and cognition.

Quantitative data will be analysed with SAS 9.4 software. Independent-sample t-tests and χ2 tests will be used to compare the baseline subject characteristics between the experimental and control groups. To clearly compare change rates between experimental and control group, over the whole trial period (baseline, 4-month, 8-month and 12-month follow-up), a repeated-measures linear mixed model will be used incorporating the intention-to-treat principle.

Research question 5—Is the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment useful, feasible and validated in Flanders?

Psychosocial interventions for caregivers need to be as person-centred as for people with dementia.51 We need to develop a validated instrument to assess the needs of informal caregivers of people with cognitive impairment and this instrument should be regularly used in healthcare.52 Thus, it is of great significance to evaluate the usefulness, feasibility and validity of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment for subsequent implementation.

Qualitative data will be collected with focus group discussions with informal caregivers. Caregivers will be asked after their baseline assessments on the following themes: whether items and scales are difficult to understand, lacking to cover carer needs and concerns, redundant, uncomfortable or unclear. These caregivers’ answers will be used as information as well as input for focus group discussions. Meantime, we will develop a focus group question guide based on the experience of using interRAI instruments in BelRAI projects, so as to help guide the group discussion towards the topics that are to be examined. Qualitative data analysis will be conducted using the NVivo software.

Discussion

This paper describes a study protocol of developing and evaluating an intervention called PROACTIVE following the Medical Research Councul (MRC) framework. First, the study aims to develop and evaluate the PROACTIVE, which is a Flemish adaptation of the New York University Caregiver Intervention (NYUCI) in the context of caregiving for older people with early cognitive decline. Second, to explore the causal mechanism among stressors and caregiver’s health and wellbeing. Third, to evaluate the validity and feasibility of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment for informal caregivers of older people with cognitive problems.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to adapt the NYUCI to informal caregivers of older people with early cognitive decline or early dementia. Challenges during care transitions (eg, lack of preparedness in initial caregiving stage) contribute to negative health outcomes for people with cognitive decline and their family caregivers.53 However, little attention is given to this critical subpopulation who are transitioning into the caregiver role of people with mild cognitive problems. Second, this study follows the methodology of MRC framework to develop and evaluate a complex intervention for informing future community implementation. The MRC framework fits the evaluation of complex interventions, guiding the process of translating research into practice, which can help address the gap between research and practice. Finally, this interdisciplinary study can systematically investigate the efficacy of the PROACTIVE intervention, beyond the scope of a single discipline, through using the combination of instruments developed from the internationally standardised interRAI assessment systems.

As the needs of informal caregivers can go unrecognised,54 we believe that the PROACTIVE intervention can work as a preventive treatment contributing to sustainable healthcare. If caregivers’ needs are not addressed timely, older people with cognitive problems and their caregivers may inadvertently undermine their health, and thus care recipients cannot remain at home for as long as possible. The PROACTIVE intervention can identify hidden caregivers’ needs and provide them with timely, person-centred support, enhance their health and well-being, subsequently contribute to ‘Healthy Ageing’. Limitations of this research should also be acknowledged. The sample of participants might not be entirely representative of the whole population in Flanders. Another limitation of the PROACTIVE intervention is that a 1-year experiment period may be relatively short to be able to measure all the effects of the intervention.

Conclusion

If the PROACTIVE intervention shows to be effective, findings will enhance the health and well-being of informal caregivers (and care recipients) and contribute to sustainable healthcare. If the validity of the interRAI Family Carer Needs Assessment is positively evaluated, this study will provide evidence for large scale implementation and provide a validated caregiver needs assessment for informal caregivers of people with cognitive problems. Process evaluation findings will facilitate subsequent community implementation. Additionally, findings may be transferable to other countries and other contexts, such as caregivers of people with chronic diseases other than cognitive problems.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors are involved in the study design and critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript. SW drafted the manuscript.

Funding: SW is supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (file no. 201806330119).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.United Nations Ageing, 2020. Available: https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/ageing/

- 2.Papastavrou E, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas SS, et al. Caring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burden. J Adv Nurs 2007;58:446–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramble M, Moyle W, McAllister M. Seeking connection: family care experiences following long-term dementia care placement. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3118–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfs CAG, Kessels A, Severens JL, et al. Predictive factors for the objective burden of informal care in people with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:197–204. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31823a6108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiao C-Y, Wu H-S, Hsiao C-Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 2015;62:340–50. 10.1111/inr.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava G, Tripathi RK, Tiwari SC, et al. Caregiver burden and quality of life of key caregivers of patients with dementia. Indian J Psychol Med 2016;38:133–6. 10.4103/0253-7176.178779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blieszner R, Roberto KA. Care partner responses to the onset of mild cognitive impairment. Gerontologist 2010;50:11–22. 10.1093/geront/gnp068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducharme F, Lévesque L, Lachance L, et al. Challenges associated with transition to caregiver role following diagnostic disclosure of Alzheimer disease: a descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1109–19. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee K, Puga F, Pickering CEZ, et al. Transitioning into the caregiver role following a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or related dementia: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;96:119–31. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Ageing: healthy ageing and functional ability, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/ageing/healthy-ageing/en/

- 11.Flemish Council for science and innovation Flanders in transition: priorities in science, technology and innovation towards 2025. Brussels: VARIO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Expertise Center Dementia Flanders The most important figures at a glance, 2020. Available: https://www.dementie.be/home/sample-page/prevalentie/

- 13.Schulz R, Beach SR, Czaja SJ, et al. Family caregiving for older adults. Annu Rev Psychol 2020;71:635–59. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthierens S, Willemse E, Remmen R. Support for informal caregivers–an exploratory analysis. health services research (hsr. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldemar G, Waldorff FB, Buss DV, et al. The Danish Alzheimer intervention study: rationale, study design and baseline characteristics of the cohort. Neuroepidemiology 2011;36:52–61. 10.1159/000322942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mello JdeA, Macq J, Van Durme T, et al. The determinants of informal caregivers' burden in the care of frail older persons: a dynamic and role-related perspective. Aging Ment Health 2017;21:838–43. 10.1080/13607863.2016.1168360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikzad-Terhune K, Gaugler JE, Jacobs-Lawson J. Dementia caregiving outcomes: the impact of caregiving onset, cognitive impairment and behavioral problems. J Gerontol Soc Work 2019;62:543–63. 10.1080/01634372.2019.1625993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ducharme FC, Lévesque LL, Lachance LM, et al. "Learning to become a family caregiver" efficacy of an intervention program for caregivers following diagnosis of dementia in a relative. Gerontologist 2011;51:484–94. 10.1093/geront/gnr014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ducharme F, Lachance L, Lévesque L, et al. Maintaining the potential of a psycho-educational program: efficacy of a booster session after an intervention offered family caregivers at disclosure of a relative's dementia diagnosis. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:207–16. 10.1080/13607863.2014.922527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garand L, Rinaldo DE, Alberth MM, et al. Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:771–81. 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garand L, Morse JQ, ChiaRebecca L, et al. Problem-Solving therapy reduces subjective burden levels in caregivers of family members with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019;34:957–65. 10.1002/gps.5095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dam AEH, de Vugt ME, Klinkenberg IPM, et al. A systematic review of social support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: are they doing what they promise? Maturitas 2016;85:117–30. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:1–8. 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittelman M. Psychosocial interventions to address the emotional needs of caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Caregiving for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. New York: Springer, 2013: 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez Hartmann M, De Almeida Mello J, Anthierens S, et al. Caring for a frail older person: the association between informal caregiver burden and being unsatisfied with support from family and friends. Age Ageing 2019;48:658–64. 10.1093/ageing/afz054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn C, Nelis SM, Martyr A, et al. Caregiver influences on 'living well' for people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL study. Aging Ment Health 2020;24:1505–13. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1602590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Coon DW, et al. Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:850–6. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Clay OJ, et al. Preserving health of Alzheimer caregivers: impact of a spouse caregiver intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:780–9. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31805d858a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drentea P, Clay OJ, Roth DL, et al. Predictors of improvement in social support: five-year effects of a structured intervention for caregivers of spouses with Alzheimer's disease. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:957–67. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long KH, Moriarty JP, Mittelman MS, et al. Estimating the potential cost savings from the new York university caregiver intervention in Minnesota. Health Aff 2014;33:596–604. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foldes SS, Long KH. The Minnesota economic model of dementia: demonstrating healthcare cost savings with the new York university caregiver support intervention. Minnesota: ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foldes SS, Moriarty JP, Farseth PH, et al. Medicaid savings from the new York university caregiver intervention for families with dementia. Gerontologist 2018;58:e97–106. 10.1093/geront/gnx077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mittelman MS, Bartels SJ. Translating research into practice: case study of a community-based dementia caregiver intervention. Health Aff 2014;33:587–95. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU caregiver intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life for adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;23:1179–92. 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaugler JE, Reese M, Mittelman MS. Effects of the Minnesota adaptation of the NYU caregiver intervention on primary subjective stress of adult child caregivers of persons with dementia. Gerontologist 2016;56:461–74. 10.1093/geront/gnu125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fauth EB, Jackson MA, Walberg DK, et al. External validity of the new York university caregiver intervention: key caregiver outcomes across multiple demonstration projects. J Appl Gerontol 2019;38:1253–81. 10.1177/0733464817714564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burns A, Mittelman M, Cole C, et al. Transcultural influences in dementia care: observations from a psychosocial intervention study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;30:417–23. 10.1159/000314860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mittelman M, Clay O, Werner P. A randomized trial of the NYU caregiver intervention in community settings in ISRAEL—ISSUES and outcomes. Innov Aging 2018;2:8 10.1093/geroni/igy023.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner P, Clay OJ, Goldstein D, et al. Assessing an evidence-based intervention for spouse caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a community implementation of the NYUCI in Israel. Aging Ment Health 2020:1–8. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1774740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990;30:583–94. 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearlin LI, Bierman A. Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013: 325–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aneshensel CS. Sociological inquiry into mental health: the legacy of Leonard I. Pearlin. J Health Soc Behav 2015;56:166–78. 10.1177/0022146515583992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mittelman MS, Epstein C, Pierzchala A. Counseling the Alzheimer’s caregiver: A resource for health care professionals. Chicago, IL: AMA Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’sullivan L, Scales LM, Duffy C. Carer needs assessment development-A Republic of Ireland led international joint working project to support delivery of integrated health and social care. Int J Integr Care 2017;17:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanneste D, Declercq A. The development of BelRAI, a web application for sharing assessment data on frail older people in home care, nursing homes, and hospitals. achieving effective integrated e-care beyond the silos. IGI Global 2014:202–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Almeida Mello J, Declercq A, Cès S, et al. Exploring home care interventions for frail older people in Belgium: a comparative effectiveness study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2251–6. 10.1111/jgs.14410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol 1994;49:M174–82. 10.1093/geronj/49.4.M174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, et al. Validation of the minimum data set cognitive performance scale: agreement with the Mini-Mental state examination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50:M128–33. 10.1093/gerona/50A.2.M128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manthorpe J, Samsi K. Person-centered dementia care: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging 2016;11:11. 10.2147/CIA.S104618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Novais T, Dauphinot V, Krolak-Salmon P, et al. How to explore the needs of informal caregivers of individuals with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease or related diseases? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:1–8. 10.1186/s12877-017-0481-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaugler JE, Roth DL, Haley WE, et al. Modeling trajectories and transitions: results from the new York university caregiver intervention. Nurs Res 2011;60:S28. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318216007d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manthorpe J, Hart C, Watts S, et al. Practitioners’ understanding of barriers to accessing specialist support by family carers of people with dementia in distress. Int J Care Caring 2018;2:109–23. 10.1332/239788218X15187915193354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.