Abstract

Objective We aimed to explore and examine how and in what ways the use of social network sites (SNSs) can improve health outcomes, specifically better psychological well-being, for cancer-affected people.

Methods Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with users of the Ovarian Cancer Australia Facebook page (OCA Facebook), the exemplar SNS used in this study. Twenty-five women affected by ovarian cancer who were users of OCA Facebook were interviewed. A multi-theory perspective was employed to interpret the data.

Results Most of the study participants used OCA Facebook daily. Some users were passive and only observed created content, while other users actively posted content and communicated with other members. Analysis showed that the use of this SNS enhanced social support for users, improved the users’ experiences of social connectedness, and helped users learn and develop social presence, which ultimately improved their psychological well-being.

Discussion The strong theoretical underpinning of our research and empirically derived results led to a new understanding of the capacity of SNSs to improve psychological well-being. Our study provides evidence showing how the integration of these tools into existing health services can enhance patients’ psychological well-being. This study also contributes to the body of knowledge on the implications of SNS use for improving the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people.

Conclusion This research assessed the relationship between the use of SNSs, specifically OCA Facebook, and the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people. The study confirmed that using OCA Facebook can improve psychological well-being by demonstrating the potential value of SNSs as a support service in the healthcare industry.

Keywords: Social network sites, Facebook, cancer-affected people, psychological well-being, social support, social connectedness, learning, social presence

INTRODUCTION

Social network sites (SNSs) are networked communication platforms on which users can create profiles and content, share content, consume content provided by their networks, establish connections with other people, and develop interactions with others.1–3

Information Systems researchers have highlighted the ability of SNSs to foster informational and emotional exchange, knowledge-sharing, and the development of extensive supportive interactions,4–8 which are predictors of better health outcomes,9–12 such as greater psychological well-being (ie, feeling happy, capable, well-supported, and satisfied with life).13–15 However, little is known about the potential for using SNSs for health promotion in populations with poor health,16 such as cancer-affected people (ie, people who have been diagnosed with cancer, including those who are either in treatment or have completed their treatment).12,17 Cancer-affected people use SNSs for exchanging informational and emotional support with others who have similar health concerns or with people who can address a cancer-related concern,18,19 but whether health-specific SNSs can improve cancer-affected people’s psychological well-being remains unknown.12

The aim of our study was to explore how and in what ways cancer-affected people’s use of a particular SNS, the Ovarian Cancer Australia Facebook page (hereafter, OCA Facebook), affects their psychological well-being. OCA Facebook is a health-related SNS that provides cancer-affected people with support, promotes cancer awareness events, connects like-minded people, and suggests positive behaviors to help individuals stay healthy while living with cancer. OCA Facebook enables people affected by ovarian cancer to connect and exchange information about their conditions, treatments, and symptoms, and support one another.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides background on and outlines the significance of the research, and defines the research question. Section 3 outlines the theoretical background of the study. Section 4 explains the research methods. Section 5 presents the study results, which are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 contains conclusions and suggestions for future research.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

The Internet is becoming an increasingly influential part of healthcare. Consumers of health services, including cancer-affected people, use the Internet to enhance their ability to communicate with others, in order to obtain health-related information, emotional support, products, and services.9,20–22 Electronic health tools, such as static health-related web applications (Web 1.0), enable cancer-affected people to acquire cancer-related information,1,12 but dynamic health-related, web-based applications (Web 2.0), such as SNSs, blogs, and forums, empower cancer-affected people to exchange health-related information and experiences,23 make sense of the information they acquire,11,18 and promote changes in health-related behaviors.24 One major advantage of SNSs over other Web 2.0 applications is that they are structured to make and display a list of friends, which enables users to maintain more intensive social interactions with other users;19 this capability is unique to SNSs.25

SNSs allow people who lack mobility or are otherwise unable to interact with others normally due to their illnesses to develop extensive supportive interactions and exchange information with like-minded people.26,27 To facilitate communication among users, SNSs such as Facebook offer various messaging services, including private and public messaging.2,28,29 In the course of information dissemination, SNSs allow users to create content on their own message board, called a “wall,” or post content to another user’s wall.3,30 Users can spread wall posts to their networks via information distribution functionalities – such as “sharing,” “liking,” and “tagging” – with only a single click.29,31 Portable web-enabled devices, such as smart phones, tablets, and laptops,32 make SNSs highly accessible to people with mobility or other communication difficulties.

Psychological well-being is defined in the literature in terms of autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, environmental mastery, and positive relatedness.33 Autonomy means being able to resist social pressures; personal growth refers to feelings of continued development of one's potential to grow; self-acceptance means holding positive attitudes toward one’s self; life purpose is defined as having a sense of direction in life; environmental mastery is related to feeling competent in creating a context that is suitable to one’s personal needs and values; and positive relatedness is the extent to which one forms satisfying relationship with others.34 Psychological well-being can also be conceptualized as feeling happy, capable, well-supported, and satisfied with life.16,35–37

A diagnosis of cancer is a life-changing event and takes a great toll on a person’s psychological well-being.36 Cancer-affected people are a growing segment of the population; they are likely to have poorer psychological well-being and mental health than healthy people and often need interventions and support.24 Developing knowledge and providing evidence of novel tools and technologies can improve cancer-related health outcomes, such as psychological well-being. Although the impacts of other Web 2.0 applications, such as blogs, forums, and chat rooms, on cancer-affected people’s psychological well-being have been explored,12 as previously noted, little is known about the impact of SNS use on the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people. Therefore, this paper addresses the research question: How and in what ways is SNS use related to the psychological well-being of people affected by cancer?

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

This study used a multi-theory perspective to guide the inquiry process and to frame the interpretation of the findings. The following section outlines the theories used in this study

Social Support Theory

Social support is the beneficial exchange of psychological and tangible resources between at least two individuals.38 Social support is defined as the exchange of emotional and informational resources between individuals through their social connections.39,40 Cutrona and Suhr41 listed five different types of social support: esteem support, emotional support, tangible support, network support, and informational support. Esteem support involves positive expressions about the support seekers’ skills and abilities. Emotional support involves caring, sympathetic, attentive, understanding, empathetic, and encouraging expressions. Network support refers to expressions of companionship and connection. Tangible (or instrumental) support involves providing needed goods and services to the support seeker. Informational support involves providing guidance, advice, facts, stories of personal experience, opinions, and referrals to other sources of information to the support seeker, as well as information that aims to eliminate or solve the support seekers’ problems or to help them evaluate situations.42 Social support in online communities measures how an individual experiences the feeling of being cared for, responded to, and assisted by people in their social networks.43,44 Various studies have used social support theory to explain the influence of individuals’ social connections on health outcomes.45

Social support has been recognized as essential for supporting positive health outcomes,46,47 such as greater psychological well-being.48,49 In one study, longitudinal predictors of change in the subjective well-being of breast cancer survivors were examined using hierarchical multiple regression; higher levels of social support were found to be associated with improvements in the study participants’ subjective well-being.50 Studies have reported that online health communities, such as online support groups, are a useful source of social support for cancer survivors.10,51 Researchers have also shown that, among breast cancer survivors, there were positive correlations between the amount of participation in online breast cancer communities (through channels such as bulletin boards) and receiving social support and, consequently, experiencing improvements psychological well-being.12,52

Various studies have shown the importance of informational and emotional exchange in improving cancer survivors’ psychological well-being,49 and others have highlighted the ability of SNSs to facilitate informational and emotional support exchange.19 Thus, the social support theory fits well within the SNS context and can be used to understand how SNS use is associated with the psychological well-being of people affected by cancer.

Belongingness Theory

Belongingness theory provides a useful lens through which to examine the powerful effects that social connections can have on improving feelings of social connectedness and, consequently, health outcomes.53,54 Social connectedness can be described as an individual’s feelings of emotional connectedness and belonging with other people.55 According to belongingness theory, individuals develop meaningful relationships to experience a sense of acceptance, and have better psychological well-being as well as better mental health as a result of such relationships.56

Studies on peer support context have shown that cancer survivors experienced a sense of belonging when participating in online support groups and that belonging to a peer network can promote feelings of optimism.57 Other studies have theorized that social connectedness is a significant, positive predictor of perceived health and well-being.58,59 Social connectedness forms through supportive interactions with other people.55 Research has highlighted the ability of SNSs to enhance supportive interactions between individuals.38 Thus, belongingness theory can explain the ability of SNS to help cancer-affected people develop supportive relationships with others and, as a result, improve their psychological well-being.

Sociocultural Theory

Scholars have used sociocultural theory (SCT) to study the power of social connections and social interactions in developing learning.60 SCT has also been used to explain the influence of learning in social environments on individuals’ psychological well-being.61 According to SCT, successful learning involves moving from object- and other-regulation to self-regulation. During the object-regulation stage, learners’ start to learn from the objects they observe in a social environment. During the other-regulation stage, learners learn by obtaining assistance and receiving feedback from peers or mentors in a social environment. During the self-regulation stage, the learner becomes competent enough to perform tasks independently.62

Studies have shown that there is a positive association between the use of Internet-based interventions, such as health-related support groups, and cancer patients’ ability to learn.63 A qualitative study on online support groups showed that the use of Scandinavian breast cancer mailing lists and feedback enabled breast cancer survivors to learn how to live with the illness. This study also reported that breast cancer survivors learning from each other about their illness and the sense of control engendered by their increased knowledge about their condition promoted feelings of psychological well-being.64

SNSs have the capability to enable users to develop interactions with others as well as to observe interactions between others;3,38 therefore, SCT is appropriate for understanding how SNS use enables people affected by cancer to observe, interact, and learn, and for understanding these behaviors’ association with psychological well-being.

Social Presence Theory

Social presence is defined as the ability to communicate effectively within a community65 or the degree to which a communication medium allows users to experience others’ presence in a social environment.32 Social presence theory (SPT), initially proposed by Short et al.,66 holds that communication is effective if the communication medium has the appropriate social presence essential for the level of interpersonal involvement required for a task. According to SPT, the degree of social presence varies in different communication media, depending on each medium’s ability to convey rapid feedback, convey non-verbal cues, and reduce communication ambiguity.

Researchers have demonstrated a positive link between the experience of social presence and enhanced satisfaction and positive feelings.67 Experiencing social presence within online environments has also been demonstrated to lead to positive health outcomes.68 Studies of interactive cancer communication systems have shown that breast cancer patients who used the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System experienced social presence and a closer connection with health professionals through the system’s discussion group, leading to increases in the patients’ emotional well-being.69

Lee and Nass70 argued that interactivity is an essential condition for social presence; other scholars have claimed that social presence requires a feeling of togetherness and mutual awareness between individuals.71 Research has shown that SNSs have a unique ability to support interactions that enable users to feel one another’s presence.31 SNSs also have the potential to support effective communication. Within Facebook, for example, users can utilize audio and video chats to communicate with other users; “tag” users in posts, pictures, videos, etc.; and “like” or “share” content to improve communication with other users.19 As previously argued, social presence, involving both in-person and virtual contact with others, is important for cancer patients. Thus, SPT is highly suited to our aim of understanding how SNS use affects the psychological well-being of cancer-affected individuals. This study applies the perspective of SPT to explain how SNS supports effective communication that leads to greater psychological well-being.

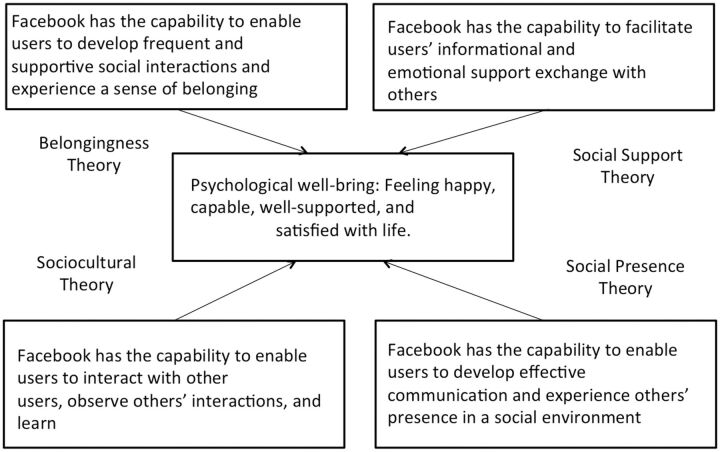

Figure 1, below, summarizes the perspectives of the theories that underpin this research.

Figure 1:

Summary of the theoretical background of the research.

The integration of these four theories provides the conceptual framework for understanding the impact of SNS use on the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people. These theories show the relationships and interrelationships mediated by SNS using different perspectives, including social connectedness, the exchange of informational and emotional support, learning, and the concept of social presence. Taken together, these theories form a framework that informs our understanding of the relationship between OCA Facebook use and the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people.

METHODS

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, an interpretive qualitative approach was used to explore the relationship between SNS use and psychological well-being. This approach was appropriate because the study’s objective was to understand the experiences of the study participants.72

Case Study and Sample

A case study approach was used for conducting in-depth investigations into and developing deep knowledge of the study participants’ SNS use and their psychological well-being.73 OCA Facebook was an appropriate SNS to use for an examination of the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people, because it is used by large numbers of cancer-affected people for exchanging informational and emotional support. In February 2014, OCA Facebook had 9499 members and an average of 16 posts, 40 comments, and 15 shares every week, suggesting that it is an active online community.20 OCA Facebook is maintained and moderated by OCA, an independent national organization that supports individuals affected by ovarian cancer. OCA Facebook offers authoritative cancer-related information, posts positive stories about staying healthy while living with cancer, and enables people affected by ovarian cancer to develop supportive interactions with others who have been similarly affected. Commercial and unrelated content as well as negative comments and posts are not permitted on OCA Facebook.

After we obtained ethical approval from Macquarie University’s ethics committee (in November 2013), the OCA Facebook administrator was contacted for permission to post an invitation to users of the OCA Facebook page to participate in an interview. Interviewees were self-selected. Choosing a study sampling approach is particularly important in qualitative research,74,75 and the goal of this research was to ensure that the study sample was representative of the target population. Interviewees had to be over the age of 18 and had to have been using OCA Facebook for >2 months.

Participants

Twenty-five women affected by ovarian cancer (mean age = 39 years old, median = 41 years old, standard deviation [SD] = 5.6) participated in this study. The sample size for this study was not predetermined but, rather, was decided by the saturation point of the data. Recruitment ceased when the information collected from a sufficiently variable sample became repetitive across individuals and new themes no longer emerged.76 This point occurred during the 25th interview. Table 1 shows some of the characteristics of our qualitative sample.

Table 1:

Interviewees’ Demographic and Other Characteristics

| Interviewee characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–25 | 2 (8) |

| 26–35 | 5 (20) |

| 36–45 | 7 (28) |

| 46–55 | 5 (20) |

| 56–65 | 6 (24) |

| Months using OCA Facebook | |

| 2–5 | 2 (8) |

| 6–11 | 4 (16) |

| 12–17 | 9 (36) |

| 18–23 | 7 (28) |

| >24 | 3 (12) |

| Interviewee residence location | |

| Melbourne | 8 (32) |

| Sydney | 5 (20) |

| Canberra | 4 (16) |

| Brisbane | 3 (12) |

| Perth | 3 (12) |

| Adelaide | 2 (8) |

OCA, Ovarian Cancer Australia.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were chosen to give the interviewer freedom to modify the format and order of the interview questions as deemed appropriate.77 The interviews were conducted via telephone, via Skype, or face-to-face, depending on the participant’s preference, in February and March 2014. Questions were phrased to allow the interviewees to tell their story in their own way, although an interview guide was used to ensure that the necessary information was gathered. Interviewees were asked 13 open-ended questions (see Supplementary Data) to gather feedback from them on their experiences using OCA Facebook, their assessments of their mental health states after using OCA Facebook, and their perceptions of the usefulness and helpfulness of OCA Facebook. Interviewees also estimated the amount of time they spent on OCA Facebook (frequency and duration) and described their history of OCA Facebook use and the specific activities they performed while using OCA Facebook. Each interview took ∼45 min and were audiotaped with the permission of the interviewees. The interviews were transcribed prior to qualitative data analysis, as outlined in the following section.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis, the process of collecting candidate themes and creating relationships between these themes, was used to identify, analyze, and report themes found in the interview transcripts.78 We analyzed the transcribed interview data using NVivo 8, a software that facilitates the coding and sorting process. Interview responses were coded in six phases: familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the final reports.79 First, each transcript was uploaded to NVivo and read several times, to obtain a sense of the entire interview. The interview text was divided into content areas based on theoretical assumptions derived from the literature. Within each content area, the text was divided into meaning units. The condensed meaning units were abstracted and labelled with a code. The various codes were compared and sorted into nodes in NVivo. Examples of meaning units, condensed meaning units, and codes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Examples of Meaning Units, Condensed Meaning Units, and Codes

| Meaning unit | Condensed meaning unit | Code |

|---|---|---|

| “OCA Facebook is more of a casual sort of method of maybe text chatting with someone or a video chat.” | Video and text chatting | Chatting |

| “News about all cancer-related events come directly to my news feed.” | Observing information through news feed | Checking news feed |

| “I feel I belong to the community that the members love me.” | Belonging to a community | Sense of belonging |

| “OCA Facebook use kept me updated because there’s so much information.” | Feel well-supported and informed | Well-supported |

| “I could learn from the people’s interaction on OCA Facebook that some tests like pap smear test is important.” | Learning from interactions with others | Learning |

| “When the doctors have told you that you might not make it to Christmas it doesn’t give you much hope, but when you use OCA Facebook and read their hopeful posted quotes and emotional sentences you say doctors are not God.” | Feeling hopeful | Hopeful |

| “I was talking to someone and commenting on her posts and then she told me that there is a trial that I might be able to be involved to.” |

|

|

| “I could meet new people and get some friendship from it and I could make sense of information provided by my doctors.” | Making good friendships | Satisfying relationship |

| “I feel a connection or something like a bond, you feel like you’ve got something in common as well because when you go through cancer, people who haven’t had cancer tell you lots of things and they really don’t know what you're going through.” | Feeling connected and having bond | Sense of belonging |

| “I feel good when I have more information related to ovarian cancer and it keeps me updated because there’s so much information. You know it’s good, it keeps you updated with everything.” |

|

|

| “I do chemo every week, once that I posted, many posts came just in a minute to say, ‘Stay positive,’ I felt positive.” |

|

|

OCA, Ovarian Cancer Australia.

Codes that were closely linked in meaning were formed into categories, creating the manifest content.72 Next, the underlying meanings – that is, the latent content – of these categories were formulated into themes. Themes were reviewed to compare and reconcile discrepancies, and themes with a similar meaning were combined in matching nodes. Throughout this process, the theme descriptions were continuously augmented and clarified to ensure that all of the study participants’ experiences were represented. Table 3 shows examples of codes, categories, sub-themes, and themes from data analysis.

Table 3:

Examples of Codes, Categories, Sub-Themes, and Themes from Data Analysis

| Codes | Categories | Sub-themes | Themes | Main theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Passive use | Type of use of OCA Facebook | Active and passive use of OCA Facebook | Using OCA Facebook improves cancer-affected people’s psychological well-being |

|

Active use | |||

|

Duration of use | Intensity of use of OCA Facebook | ||

|

Frequency of use | |||

|

Pleased and feeling good | Happy and satisfied | Experiencing psychological well-being | |

|

Feeling hopeful and positive | Hopeful | ||

|

Able to resist cancer-related pressures | Capable | ||

|

Feeling connected | Social connectedness | Factors that mediate the relationship between OCA Facebook and psychological well-being | |

|

Obtaining informational and emotion exchange | Social support | ||

|

Obtaining knowledge and views | Learning | ||

|

Experiencing effective communication | Social presence |

OCA, Ovarian Cancer Australia.

Rigor was addressed in this study by following Yin’s guidelines73 with respect to construct validity and internal validity. To ensure construct validity, two techniques were used. The first was triangulation through the use of multiple sources of evidence, including the authors’ own systematic literature review on the use of internet-based interventions for cancer-affected people.19 The second technique was to have interviewees review the case study reports to ensure the accuracy of the transcription, establishing a chain of evidence through the use of a case study repository. Internal validity was addressed by carefully selecting cases and interviewees, using sound data collection procedures, selecting the correct theories, and conducting a literature review.

Reliability was addressed in this study by using a case study protocol for all of the interviews, using a case study repository to store all of the study data, and conducting a pilot study to ensure that the interview questions used for the study were appropriate. Conducting a pilot study, as advised by Neuman,80 can increase the reliability of the main study’s results. A preliminary study with five cancer patients was conducted to assess the feasibility of investigating the research topic with cancer-affected people, and this preliminary study confirmed our work’s feasibility.

RESULTS

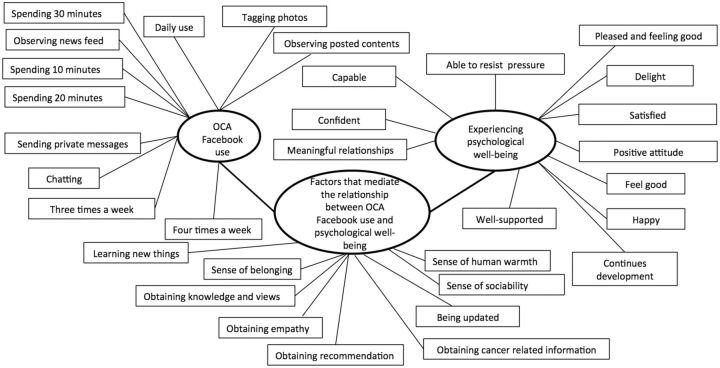

Our analysis of the interview data revealed three major themes. Figure 2 depicts the emergent themes and sub-themes from this study and the relationships between them. Each theme is explained in detail in the following paragraphs.

Figure 2:

Thematic map of social network site (SNS) use and psychological well-being. The themes shown in circles are: active and passive use of OCA Facebook, experiencing psychological well-being, and factors that mediate the relationship between OCA Facebook and psychological well-being.

Active and Passive Use of OCA Facebook

This theme included two sub-themes: type of OCA Facebook use (active use and passive use) and intensity of OCA Facebook use.

Four interviewees reported that they only passively participated in engaging with others on OCA Facebook, while the remainder of interviewees (n = 21) were both actively and passively engaged in OCA Facebook use. Active use of OCA Facebook included activities such as chatting with other users, “liking” content, creating content, and sending messages to other users. The following quotations from the interviews describe how interviewees actively used OCA Facebook:

“I comment on posts on OCA Facebook and I like the shared information.” (Interviewee #3)

“I chat with people on OCA Facebook and also send them private messages.” (Interviewee #19)

Passive use of OCA Facebook included observing the content generated by other users and monitoring posts. The following quotations from the interviews describe how interviewees passively used OCA Facebook:

“There are people who have written about their mothers that are doing well. I read their stories.” (Interviewee #4)

“I see anything OCA Facebook shares since they come up on my news feed.” (Interviewee #12)

In this study, the measurement of intensity of use is considered to be a combination of duration and frequency. Duration of use is the amount of time the interviewees spent on OCA Facebook per visit. Frequency of use refers to the number of times that the interviewees visited the OCA Facebook page per week. The average duration per visit was 11 min. Means were calculated with outliers removed, to decrease the large degree of variability (an outlier was defined as any value falling >2 SDs above or below the mean duration per visit). There were two outliers for duration of OCA Facebook use, both at the very high end of the distribution. With the outliers removed, the mean duration of passive OCA Facebook use was 11.8 min per visit (SD = 6.73, median = 15.00), and the mean duration of active OCA Facebook use was 11 min per visit (SD = 5.53, median = 10.00).

Most interviewees (n = 19, or 76%) used OCA Facebook daily. Five used OCA Facebook four times per week, and one interviewee used OCA Facebook 3 days per week. On average, the interviewees had been using OCA Facebook for 14 months (SD = 5.3).

Experiencing Psychological Well-Being

This theme emerged when cancer-affected people reported feeling good, positive, happy, well-supported, and hopeful as a result of OCA Facebook use. The interviewees felt that OCA Facebook use significantly enhanced their positive emotions and they felt supported as a result of using the site. OCA Facebook use helped them develop satisfying relationships with others, met their social needs, empowered them to resist cancer-related pressures, and encouraged them to continue improving their health. The following quotations from the interviews illustrate this point:

“Using OCA Facebook makes me feel positive about myself.” (Interviewee #1)

“Using OCA Facebook made me feel positive and I believe that I can overcome cancer-related pressures and fight with cancer.” (Interviewee #5)

“I could meet new people and get some friendship from it and I could make sense of information provided by my doctors.” (Interviewee #21)

Factors That Mediate the Relationship Between OCA Facebook and Psychological Well-Being

This third theme had four sub-themes: experiences of social connectedness, enhanced reception of social support, learning, and development of social presence.

The experiences of social connectedness sub-theme emerged from 80% of the interviewees’ transcripts; they reported that using OCA Facebook gave them a sense of belonging and enabled them to form satisfying relationships with others. For example, one interviewee noted that:

“I feel I belong to the community that is specific for people like me and cares about me and I feel good about myself.” (Interviewee #12)

The enhanced reception of social support sub-theme emerged from 78% of the interviewees’ transcripts, indicating that using OCA Facebook enabled them to receive recommendations, advice, caring, understanding, and empathy by chatting with other users, creating content, and observing content posted by others. These benefits led interviewees to feel well-supported and able to resist social pressures. For example, interviewees noted that:

“When doctors have told you that you might not make it to Christmas it doesn’t give you much hope, but when you use OCA Facebook and read their hopeful quotes you say doctors are not God and they don’t know what is going to happen so, yes, look, there is emotional support there and it does make you positive.” (Interviewee #6)

“I was talking to someone and commenting on her comments then she told me that there is a trial that I might be able to be involved to, there is so much information that you need.” (Interviewee #4)

The learning sub-theme emerged from 65% of the interviewees’ transcripts, indicating that using OCA Facebook enabled them to learn new things and to feel they were continuously developing their personal potential to overcome cancer related concerns. OCA Facebook use had an important influence on interviewees’ thoughts, attitudes, and learning. Learning new things from other members of the group about what works and what does not work, and learning from stories shared by other members of the group about past or present situations that are similar to theirs, helped the study participants feel more positive and encouraged them to continue learning about their condition. The following is an example of the interviewees’ comments about how they were able to learn by using OCA Facebook:

“I could learn healthy diets from other people on OCA Facebook and I could feel good and like to learn more.” (Interviewee #20)

“Using OCA Facebook helped me to learn about my illness and cancer risks, and I learned different ways to cope with my illness.” (Interviewee #5)

The development of social presence theme emerged from 72% of the interviewees’ transcripts, indicating that using OCA Facebook enabled them to meaningfully communicate with others and have the sense of being with others. The study participants believed that the use of OCA Facebook enabled them to feel the presence of others through obtaining private or public messages, “liking” comments or other content, “tagging” photos, and sharing content with others. They also noted that the technical features of this SNS enabled them to communicate aurally and visually with others, making them feel more satisfied and helping them meet their social needs. The following example describes one interviewee’s experience of social presence in the OCA Facebook environment:

“Communication on OCA Facebook is completely understandable since you can use different tools for delivering your message, such as posting photos, conducting video chats, all of them that would decrease ambiguity which allows you to understand what you need and experience more pleasing feelings.” (Interviewee #14)

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the use of SNSs, and in particular OCA Facebook, was one of cancer-affected people’s daily activities and had a positive impact on their psychological well-being, regardless of whether they used the site actively or passively. Our findings expand on previous research that showed that the use of online health-related resources, such as blogs and forums, was associated with increased psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors,12 and are consistent with the findings of studies that showed that SNS use is integrated into individuals’ lives and positively impacts their psychological well-being.16,81 The present study’s participants reported that using OCA Facebook enhanced their experiences of social connectedness, reception of social support, learning, and effective communication with others (development of social presence) – and ultimately increased their happiness, satisfaction, feelings of being well-supported, and positive attitudes all indicators of psychological well-being.33

The study participants described feeling a sense of belonging with other people when they used OCA Facebook. The use of OCA Facebook helped cancer-affected people fulfil their social needs, achieve positive attitudes, and form satisfactory relationships with others. This is consistent with belongingness theory and previous studies that found that experiencing social connectedness in social environments is positively associated with a good mood and greater psychological well-being.57,58

The use of OCA Facebook enabled cancer-affected people to experience the feeling of being cared for, responded to, and assisted by people in their social community, and to feel positive and well-supported. This is consistent with social support theory and studies that hold that these kinds of support can only be achieved by forming connections with others and also play an important role in keeping individuals informationally and emotionally supported as well as in enabling them to experience improved psychological well-being.50

Using OCA Facebook helped cancer-affected people learn new things through both passive and active use of the site and also helped increase their motivation to continue development of their personal potential to manage and control cancer related problems. These findings are consistent with SCT, which explains that learning occurs through observing others’ interactions and developing interactions with others in a social environment.60 In addition, these findings are similar to those of previous research that showed that learning in a social setting was associated with greater well-being.63,64

OCA Facebook use enhanced the social presences of the study participants. OCA Facebook allowed study participants to use various online services for communicating and developing informationally and emotionally supportive exchanges with others. These services included video and audio chatting, photo tagging, and content-sharing tools that could support the use of natural language as well as carry verbal and non-verbal cues associated with effective communication. As a consequence, the study participants reported feeling more satisfied and positive than before they began using OCA Facebook. This is in line with SPT, which holds that communication is effective if the medium of communication can support the social presence required for a task, and also with previous studies that showed that there is a reciprocal relationship between an individual’s level of social presence and their satisfaction with life.69

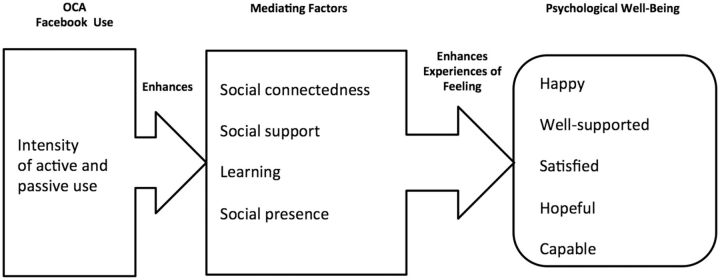

Based on these findings, a theoretical model of OCA Facebook and the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people was proposed (Figure 3). OCA Facebook use is represented by intensity of use and type of use. Four mediating factors are shown: social connectedness, social support, learning, and social presence. Through these mediating factors, OCA Facebook use is associated with greater psychological well-being among cancer-affected people.

Figure 3:

Theoretical model of OCA Facebook use and the psychological well-being of people affected by cancer.

This study provided insights into the real experiences of cancer-affected people’s use of SNSs. This contributes to a better understanding of the ways that SNS use is associated with the psychological well-being of cancer patients. By clarifying this relationship, this study demonstrates that SNS use does indeed have possibilities for promoting psychological well-being among cancer-affected people, arguing for the sustainability of Internet-based interventions and showing the advantages that SNS use can have in the context of healthcare, particularly with respect to cancer-affected people. This study focused on OCA Facebook, but our findings are generalizable to other SNSs with similar characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This research assessed the relationship between SNS use and the psychological well-being of people affected by ovarian cancer. Our findings show a positive relationship between OCA Facebook use and psychological well-being, mediated through social connectedness, social support, learning, and social presence. This contributes to a better understanding of the ways in which SNS use is associated with the psychological well-being of cancer-affected people. Our results will help health organizations generate policies for using SNSs to improve the psychological well-being of patients. These findings should encourage organizations and cancer-affected individuals to use health-related SNSs to improve their psychological well-being.

Future empirical studies should be conducted to quantitatively and longitudinally examine the relationship between SNS use, its mediating factors, and the psychological well-being of users. Organizations should consider introducing strategies for using SNSs as an online support resource, to enhance patients’ psychological well-being. Future studies could examine the effects of using other public or private SNSs and content-oriented sites on users’ psychological well-being.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the study participants for sharing their time and personal experiences. The authors would like to thank Ovarian Cancer Australia for their advice. The authors are also grateful to the Editor, Associate Editor, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

CONTRIBUTORS

All the listed authors contributed substantially to the conception and design or analysis and interpretation of data. All the authors contributed drafts and revisions to the manuscript and approved the current revised version. No person who fulfills the criteria for authorship has been left out of the author list.

FUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Data is available online at http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Von Muhlen M Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. JAMIA. 2012;19(5):777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ellison NB Boyd D. Sociality through social network sites. The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies. Cambridge, MA: Oxford University Press; 2013:151–172. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berger K Klier J Klier M et al. . A review of information systems research on online social networks. Commun Assoc Inform Syst. 2014;35(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oh H Ozkaya E LaRose R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput Human Behav. 2014;30:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pan Y Xu YC Wang X et al. . Integrating social networking support for dyadic knowledge exchange: a study in a virtual community of practice. Inform Manag. 2015;52(1):61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Utz S. The function of self-disclosure on social network sites: not only intimate, but also positive and entertaining self-disclosures increase the feeling of connection. Comput Human Behav. 2015;45:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin TC Hsu JSC Cheng HL et al. . Exploring the relationship between receiving and offering online social support: a dual social support model. Inform Manag. 2015;52(3):371–383. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zagaar U Paul S. Knowledge sharing in online cancer survivorship community system: a theoretical framework. AMCIS. 2012; paper 20. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nambisan P. Information seeking and social support in online health communities: impact on patients' perceived empathy. JAMIA. 2011;18(3):298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bui N Yen J Honavar V. Temporal causality of social support in an online community for cancer survivors. In Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling, and Prediction, Vol. 9021 Springer International Publishing; 2015:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shaw BR Han JY Baker T Witherly J et al. . How women with breast cancer learn using interactive cancer communication systems. Health Edu Res. 2007;22(1):108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hong Y Pena-Purcell NC Ory MG. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Patient Edu Counselling. 2012;86(3):288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu H Li S Xiao Q Feldman MW. Social support and psychological well-being under social change in urban and rural China. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119(2):979–996. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinecke L Trepte S. Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: a two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Comput Human Behav. 2014;30:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nabi RL Prestin A So J. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsych, Behav Soc N. 2013;16(10):721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo Y Li Y Ito N. Exploring the predicted effect of social networking site use on perceived social capital and psychological well-being of Chinese international students in Japan. Cyberpsych, Behav, Soc N. 2014;17(1):52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erfani SS Abedin B. Effects of web based cancer support resources use on cancer affected people: a systematic literature review. Int Technol Manag Rev. 2014;4(4):201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bender JL Jimenez-Marroquin MC Jadad AR. Seeking support on Facebook: a content analysis of breast cancer groups. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Erfani S Abedin B. Investigating the impact of Facebook use on cancer survivors' psychological well-being. Proceedings of the 19th American Conference on Information Systems. Chicago, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hajli MN. Developing online health communities through digital media. Int J Inform Manag. 2014;34(2):311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laranjo L Arguel A Neves AL et al. . The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMIA. 2015;22(1):243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li J. Privacy policies for health social networking sites. JAMIA. 2013;20(4):704–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feeley TW Sledge GW Levit L et al. . Improving the quality of cancer care in America through health information technology. JAMIA. 2013;21(5):772–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McLaughlin M Nam Y Gould J et al. . A video sharing social networking intervention for young adult cancer survivors. Comput Human Behav. 2012;28(2):631–641. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ellison NB Steinfield C Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook friends: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Mediat Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erfani SS Abedin B Daneshgar F. A qualitative evaluation of communication in Ovarian Cancer Facebook communities. International Conference on Information Society (i-Society). 2013:270–272. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farmer A Holt CEMB Cook M et al. . Social networking sites: a novel portal for communication. Postgraduate Med J. 2009;85:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martínez-Núñez M Pérez-Aguiar WS. Efficiency analysis of information technology and online social networks management: an integrated DEA-model assessment. Inform Manag. 2014;51(6):712–725. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heidemann J Klier M Probst F. Online social networks: a survey of a global phenomenon. Comp Networks. 2012;56(18):3866–3878. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burke M Marlow C Lento T. Social network activity and social well-being. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems ACM. 2010:1909–1912. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abedin B Jafarzadeh H. Relationship development with customers on Facebook: a critical success factors model. Proceedings of 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). Hawaii, USA: IEEE Computer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu C Ryan S Prybutok V et al. . It is not for fun: an examination of social network site usage. Inform Manag. 2012;49(5):210–217. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huppert FA. Psychological well-being: evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Appl Psychol: Health and Well-Being. 2009;1(2):137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winefield HR Gill TK Taylor AW et al. . Psychological well-being and psychological distress: is it necessary to measure both? Psychol Well-Being. 2012;2(1):1–14.23431502 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moyer A Goldenberg M Schneider S et al. . Psychosocial interventions for cancer patients and outcomes related to religion or spirituality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psycho-Soc Oncol. 2014;3(1). http://www.npplweb.com/wjpso/content/3/1 Accessed May 9, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chou AY Lim B. A framework for measuring happiness in online social networks. Issues Inform Syst. 2010;11(1):198–203. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shumaker SA Brownell A. Toward a theory of social support: closing conceptual gaps. J Social Issues. 1984;40(4):11–36. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caplan G. Support systems and community mental health: lectures on concept development. Behavioral Publications. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hajli MN. The role of social support on relationship quality and social commerce. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2014;87:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cutrona CE Suhr JA. Controllability of stressful events and satisfaction with spouse support behaviors. Commun Res. 1992;19(2):154–174. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, et al. Measuring the functional components of social support. Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications, Vol. 24 Netherlands: Springer; 1985:73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang M Yang CC. Using content and network analysis to understand the social support exchange patterns and user behaviours of an online smoking cessation intervention program. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol. 2015;66(3):564–575. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Med. 1976;38(5):300–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eastin MS LaRose R. Alt.support: modeling social support online. Comput Human Behav. 2005;21(6):977–992 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Noronha AME Mekoth N. Social support expectations from healthcare systems: antecedents and emotions. Int J Healthcare Manag. 2013;6(4):269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Penwell LM Larkin KT. Social support and risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer: a qualitative review examining the role of inflammatory processes. Health Psychol Rev. 2010;4(1):42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Melrose KL Brown GD Wood AM. When is received social support related to perceived support and well-being? When it is needed. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;77:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaniasty K. Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: the role of post-disaster social support. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4(1):22. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neuling SJ Winefield HR. Social support and recovery after surgery for breast cancer: frequency and correlates of supportive behaviours by family, friends and surgeon. Social Sci Med. 1988;27(4):385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kreps GL Neuhauser L. New directions in eHealth communication: opportunities and challenges. Patient Educ Counseling. 2010;78(3):329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rodgers S Chen Q. Internet community group participation: psychosocial 20 benefits for women with breast cancer. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2005;10(4). http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10no4/rodgers.htm. Accessed March 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yoon E Hacker J Hewitt A et al. . Social connectedness, discrimination, and social status as mediators of acculturation/enculturation and well-being. J Counselling Psychol. 2012;59(1):86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grieve R Indian M Witteveen K et al. . Face-to-face or Facebook: can social connectedness be derived online? Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(3):604–609. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee RM Robbins SB. Measuring belongingness: the social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J Counseling Psychol. 1995;42(2):232. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baumeister RF Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Morris BA Lepore SJ Wilson B et al. . Adopting a survivor identity after cancer in a peer support context. J Cancer Survivorship. 2014; 8(3):427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Galloway AP Henry M. Relationships between social connectedness and spirituality and depression and perceived health status of rural residents. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2014;14(2):43–79.26029005 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abubakar A Van de Vijver FJ Mazrui L et al. . Connectedness and psychological well-being among adolescents of immigrant background in Kenya. In Global Perspectives Well-Being Immigrant Families, New York: Springer; Vol. 1 2014:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lantolf JP. Sociocultural theory and second language learning: introduction to the special issue. Modern Lang J. 1994;78(4):418–420. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Watkins KW Connell CM Fitzgerald JT et al. . Effect of adults’ self-regulation of diabetes on quality-of-life outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(10):1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lantolf JP. Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. UK: Oxford University Press; 2000:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gustafson DH McTavish FM Stengle W et al. . Use and impact of eHealth system by low-income women with breast cancer. J Health Commun. 2005;10(S1):195–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Høybye MT Johansen C Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T. Online interaction. Effects of storytelling in an Internet breast cancer support group. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(3):211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ning Shen K Khalifa M. Exploring multidimensional conceptualization of social presence in the context of online communities. J Human–Comput Inte. 2008;24(7):722–748. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Short J Williams E Christie B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. UK: Wiley, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu IL Cheung CM Lee MK. User satisfaction with microblogging: information 60dissemination versus social networking. J Assoc Inform Sci Technol. 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/asi.23371/abstract. Accessed April 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kumar N Benbasat I. Para-social presence: a re-conceptualization of “social presence” to capture the relationship between a web site and her visitors. 35th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii. 2002:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Walther JB Pingree S Hawkins RP et al. . Attributes of interactive online health information systems. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(3):e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee KM Nass C. Designing social presence of social actors in human computer interaction. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in Computing Systems ACM. 2003:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Biocca F. The cyborg dilemma: progressive embodiment in virtual environments. J Comput-Mediat Commun. 1997;3(2). http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol3no2/biocca2.html. Accessed September 5, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kurnia S Karnali RJ Rahim MM. A qualitative study of business-to-business electronic commerce adoption within the Indonesian grocery industry: a multi-theory perspective. Inform Manag. 2015;52(4):518–536. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. California: Sage; 2013:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice. 1996;13(6):522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Silverman D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. New York (NY): SAGE Publications Limited; 2013:61–50. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Francis JJ Johnstone M Robertson C et al. . What is an adequate sample size? Operationalizing data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. USA: Sage Publications; 2013:60–74. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vaismoradi M Turunen H Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Braun V Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Neuman WL. Social Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2005;13:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Valkenburg PM Peter J Schouten AP. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyber Psychol Behav. 2006;9(5):584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.