Abstract

The over-purchasing and hoarding of necessities is a common response to crises, especially in developed economies where there is normally an expectation of plentiful supply. This behaviour was observed internationally during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. In the absence of actual scarcity, this behaviour can be described as ‘panic buying’ and can lead to temporary shortages. However, there have been few psychological studies of this phenomenon. Here we propose a psychological model of over-purchasing informed by animal foraging theory and make predictions about variables that predict over-purchasing by either exacerbating or mitigating the anticipation of future scarcity. These variables include additional scarcity cues (e.g. loss of income), distress (e.g. depression), psychological factors that draw attention to these cues (e.g. neuroticism) or to reassuring messages (eg. analytical reasoning) or which facilitate over-purchasing (e.g. income). We tested our model in parallel nationally representative internet surveys of the adult general population conducted in the United Kingdom (UK: N = 2025) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI: N = 1041) 52 and 31 days after the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were detected in the UK and RoI, respectively. About three quarters of participants reported minimal over-purchasing. There was more over-purchasing in RoI vs UK and in urban vs rural areas. When over-purchasing occurred, in both countries it was observed across a wide range of product categories and was accounted for by a single latent factor. It was positively predicted by household income, the presence of children at home, psychological distress (depression, death anxiety), threat sensitivity (right wing authoritarianism) and mistrust of others (paranoia). Analytic reasoning ability had an inhibitory effect. Predictor variables accounted for 36% and 34% of the variance in over-purchasing in the UK and RoI respectively. With some caveats, the data supported our model and points to strategies to mitigate over-purchasing in future crises.

Introduction

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic news outlets around the world reported what was widely described as “panic buying” of a wide range of household commodities, but especially toilet rolls [1], which led to temporary shortages in Australia, Italy, Japan, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States [2]. These observations have recently been confirmed in a study of bar code data in the UK [3] and in an analysis of credit card transactions in Australia [4]. Here we review the scant existing literature on consumer purchasing during crises, propose a psychological model of over-purchasing and then test it in representative samples from the populations of the United Kingdom (UK) and Republic of Ireland (RoI).

Historical background and basic concepts

Although rarely recorded before the beginning of the twentieth century, excessive purchasing and hoarding of essentials, sometimes leading to scarcity of basic goods, has since been observed during many crises. This has especially been the case in populations living in comfortable circumstances in which there is ordinarily an expectation of unbroken access to essential commodities. It occurred, for example, during both world wars, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the 1979 oil crisis [5] and has also been observed during natural disasters such as earthquakes [6] and other pandemics [2]. When Spanish flu arrived in Britain immediately after the First World War, the rush to purchase quinine and other medications led to the threat of shortages [7], and during the 2003 SARS pandemic, over-purchasing in China and Hong Kong led to actual—albeit temporary—shortages of salt, rice, vinegar, vegetable oil, masks, and medicines [8].

It is important to note that human behaviour observed during a crisis, far from evidencing a panic-driven breakdown of the social order, is often adaptive [9]. Hoarding the necessities of life in anticipation of supply-side scarcity is a rational survival strategy. Indeed, in the US, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommends that all households hold a stockpile of two weeks of non-perishable foodstuffs [10] and households are advised to take similar measures in earthquake-prone regions of Japan and New Zealand where non-compliance is seen as a social problem [11]. Over-purchasing, which we define as buying more than is necessary to sustain a household during routine life (see Table 1), primarily becomes problematic when it creates demand-side scarcity, stimulating further over-purchasing and potentially a vicious cycle of demand outstripping supply. In some circumstances, this can occur in the absence of actual supply-side scarcity at the outset, in which case the term ‘panic buying’ seems appropriate.

Table 1. Definitions.

| 1. Over-purchasing: buying more than is necessary to sustain a household during routine life, as evidenced by increased purchasing compared to a previous period. Extreme over-purchasing may lead to demand-side scarcity, as stocks become depleted in retail outlets. |

| 2. Panic buying: Over-purchasing in the absence of supply-side scarcity. |

| 3. Hoarding: The storing of essentials for use at a later time. In both human and nonhuman animals, hoarding is an insurance policy against the event of future scarcity. |

| 4. Scarcity cue: Any cue or information indicating the likelihood of future scarcity. |

For example, an economic study of the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami and earthquake in Japan, which used supermarket barcode data to compare household purchasing before and during the crisis, found considerable variation in the extent to which households over-purchased. Importantly, those households which excessively purchased did so across a wide range of commodities, implying a general tendency to over-purchase rather than the selective hoarding of specific necessities that were in danger of short supply [6].

Over-purchasing, panic buying and hoarding therefore appear to be social psychological phenomena that vary between individuals and therefore households. However, the mechanisms that lead to this behaviour have been subjected to very little psychological research. In a recent systematic review [12], 27 relevant publications were identified that were predominately within the business, management, and accounting literature. Many of these papers were non-empirical, concerned with responses to non-distaster related scarcity [13] focused on the performance of supply chains and retailers [14], or involved economic models [15], simulations [16], or surveys about likely behaviour in a crisis [11]. Four themes relating to potential psychological mechanisms were identified in the review: the perception of threat and scarcity, fear of the unknown, panic buying as a form of coping bahviour, and social influences such as the observed behaviour of others and lack of social trust.

In the context of the current coronavirus pandemic, some researchers have considered personality factors that may contribute to over-purchasing, such as the six-dimensions (honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience) of the HEXACO model of personality [17]. In two internet surveys in the UK conducted in early March 2020 [18], the personality dimension of honesty-humility was modestly associated with negative responses to the question, “I have bought more food or supplies than usually” and with reduced intentions to over-purchase in future. These findings were interpreted as evidence that those individuals who refrained from over-purchasing were motivated to maximise societal outcomes, even if this required forgoing individual benefits. However, this finding was not replicated in a subsequent study with an internet convenience sample from 35 countries that focused specifically on toilet roll purchasing [19]. The authors of this study found that over-purchasing was predicted by the HEXACO dimension of conscientiousness–which was interpreted as evidence that more prudent individuals tend to stockpile–and also that an indirect association between emotionality and over-purchasing was mediated by anxiety about COVID-19.

We think that research on over-purchasing is likely to be more fruitful if based on a clear theoretical model. Here we outline a model that treats over-purchasing and panic buying as responses to the perceived threat of uncertain supplies, and report a preliminary test of our model using survey data collected from the UK and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) during the early stages of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

A consumer foraging model

Searching for food and other essential resources is a near-ubiquitous behaviour across the animal kingdom, including the human species [20–22] which has spent most of its evolutionary history in foraging economies [23]. In developed economies, the resources necessary for survival are typically obtained from shops and supermarkets. Consumers’ choices about which supplier to visit typically obey a ‘gravity model’ (more often used to predict trading between nations [24] in which, other factors being equal, larger suppliers that are nearer to home are preferred [25, 26].

Research into animal patch foraging provides a framework for understanding how consumers evaluate the trade-off between exploiting known, local resources and travelling to distant locations where there is an unknown distribution of rewards [27]. In the simple context of supermarket purchases, this is the choice between buying goods from a local supermarket, which has an observable distribution of goods (e.g. canned goods, dried food), or sacrificing the cost in time and effort required to travel to a more distant supermarket where the abundance of these goods is unknown [28]. Decisions of this kind require the individual to track two parameters: the directly observable rewards that are available at the known patch, termed the foreground rate, and the rewards that can be expected from exploring the unknown patch, estimated from the organism’s past encounters with similar patches in that environment, known as the background rate [29].

According to Charnov’s marginal value theorem [20], in a stable environment the forager should explore a novel resource when the foreground rate falls below the background rate. This policy should maximise the ability to maintain energetic homeostasis, such that the organism does not expend more energy than it accumulates, nor acquires more energy than is necessary for survival [30]. However, this policy is likely to be ineffective or difficult to implement in an unstable environment in which the background rate is falling rapidly. Indeed, if the background rate is falling faster than the foreground rate, the marginal rate theorem mandates continued foraging in the home patch even though this strategy may ultimately lead to the patch becoming completely depleted and hence starvation. In the face of this kind of risk to survival, but before depletion occurs, accumulating energy for future use may be an effective insurance strategy that can be achieved in two ways: first, by hoarding supplies so that they can be retrieved later [31] and, second, by consuming more than is required to maintain energetic homeostasis [30]. Hence, priming human participants with cues that indicate future scarcity leads to increased consumption of high calorific food items [32]. Furthermore, in wealthy economies with easy access to these kinds of foods, distance to supermarkets where fresh produce is available [26] and food insecurity [33] are both associated with unhealthy diets and obesity.

A complication in this traditional account of foraging is that the background rate cannot be observed directly; it must therefore be inferred from whatever information is available. In a political crisis or natural disaster, judgments about the uncertainty of future supplies are likely to be informed by news reports of unfolding events [34, 35], which may be subject to rapid and unpredictable change, and also by the behaviour of other consumers. Hence, the depletion of stocks on supermarket shelves caused by people who have already engaged in panic buying may create a powerful scarcity cue that suggests that the availability of necessities in the future cannot be guaranteed. What begins with reports of shortages of particular products may therefore escalate into the panic buying of a wide range of goods. In many countries, these reported shortages began with toilet paper, possibly because they are large items that are most conspicuous when absent from the shelves [36] or because fear of the virus activates feelings of disgust [37] according to two speculative accounts. In an attempt to prevent further demand-side scarcity, politicians, emergency services, and supermarket managers may attempt to deliver reassuring messages (e.g. [38]) designed to persuade consumers that supplies will be rapidly replenished—that is, that the background rate is not falling.

The application of foraging theory to this context complements work that has examined the effects of manipulating product availability on consumers’ behaviour. In fact, the manipulation of scarcity cuse is a common and effective marketing method used to increase the demand for products [39]. Foraging theory presents a lense through which to understand the efficacy of such marketing tactics; through presenting cues that the environment is poorer in resources (i.e. fewer items are available), the forager should infer a lower background rate and hence forage the current patch more extensively [20]. Notably, it has been observed that it is the popularity of items, rather than their exclusivity that drives this scarcity effect, suggesting this relies on the behaviour of other consumers rather than retailers [40]. This is consistent with evidence that observing others engaging in panic purchasing positively associated with increased consumer’s own over-purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic [15]. Hence, the behaviour of other consumers can be an important scarcity cue indicating a fall in the background rate.

A further parameter that affects foraging behaviour in animals is the risk of predation. While viruses are parasites, rather than predators, the nature by which the virus spreads, i.e. through close contact with other human beings, should increase vigilance and subsequently lead to other people becoming associated with a threat to life [28]. In order reduce exposure to infection, individuals who perceive a high risk of infection should increase their foraging effort to hoard a greater amount of resources to maximise inter-foraging delays and minimise the frequency of encounters that put the individual at risk. Therefore, along with tracking scarcity cues, perceived risk of infection should predict over-purchasing behaviour.

Demographic, situational and individual differences factors associated with over-purchasing, panic buying, and hoarding

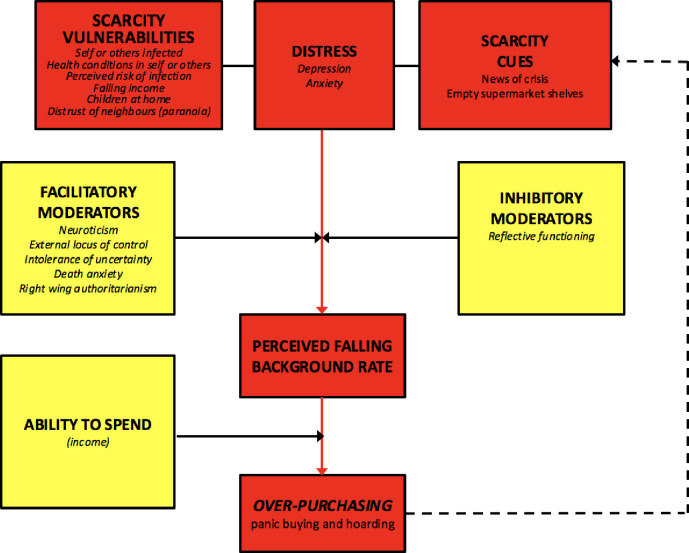

Drawing on foraging theory, we have argued that over-purchasing, panic buying, and hoarding occur when individuals perceive that the background rate is falling rapidly, and that this perception is stimulated by scarcity cues in the form of news reports (balanced by reassuring messages) and also by directly observed cues such as shortages (see Fig 1). Using this framework, we identify three kinds of variables that may either exacerbate or mitigate against over-purchasing.

Fig 1. Proposed model of factors influencing over-purchasing during a crisis.

Variables measured in the present study in italics.

First, some demographic and situational factors may confer vulnerability to future scarcity. These factors can be considered to contribute to the overall salience of scarcity cues which, according to our foraging account, should motivate increases in purchasing behaviour. In this first type of variable, exposure to the coronavirus or being close to someone else who has been exposed, or pre-existing health conditions that confer vulnerability to self or someone close might be expected to signal reduced future access to shops, and therefore risk of scarcity. Household size might also be expected to have the same effect because a greater number of mouths to feed implies direr consequences if stocks cannot be replenished. Consistent with this account, household size predicted over-purchasing in the Tōhoku tsunami and earthquake [6]. Given that economic hardship [41] and food insecurity [42, 43] are a major source of psychological distress in parents, we predict that households with children will show a greater propensity for over-purchasing. The threat of economic loss associated with the pandemic, signalling reduced ability to secure supplies in the future, might also be expected to lead to a tendency to hoard while this is still possible (although see below). Food security in times of uncertainty might well depend on alliances with neighbours. As such, we also predict that the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood (which we have previously shown is protective against the stress associated with financial hardship [44]) and trusting relationships with neighbours will also mitigate against over-purchasing because these kinds of relationships will signal support from others in the event of depleted supplies. Conversely, paranoia (which we have previously shown is associated with harsh neighbourhoods in which trust is low [45]) should be associated with a greater tendency to over-purchase. Finally, we predict that perceived risk of infection should be associated over-purchasing, as this should increase effort to hoard resources in order to reduce the frequency of shopping trips and subsequently future risk of infection.

The salience of scarcity cues is likely to provoke negative emotional reactions. In the context of foraging theory, the stress response, provoked by aversive changes in the environment, should lead to greater exploitation of known patches [29]. Indeed, there is evidence that experimentally-induced stress, measured both physiologically and by subjective reports, is associated with the tendency to exploit a known resource for longer and engage in less frequent exploration [46]. Thus, indices of stress such as depression, anxiety, and specific anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic (as reported by [19]) should be associated with greater over-purchasing.

A second type of variable that should influence over-purchasing is any individual difference factor that affects attention to scarcity cues or perceived risk of infection. These factors might include neuroticism [47], or traits which enhance perceptions of limited personal control over and uncertainty about the future, for example an external locus of control [48] and intolerance of uncertainty [49], or which indicate an enhanced perception of existential threat such as death anxiety [50]. Amongst political dispositions, right wing authoritarianism should also predict over-purchasing as this ideology is associated with sensitivity to both social [51] and existential threat [52]. Conversely, it is possible that some individual difference variables will predict a tendency not to panic buy. In particular, the capacity to reflect and think about reassuring messages [53, 54] when faced with signals of future uncertainty is likely to be an inhibitory factor.

Finally, it is important to consider variables that affect the ability to over-purchase given the perception that the background rate of supermarket goods is falling. Important amongst these is household income. In the Tōhoku tsunami and earthquake disaster, wealthier households were observed to over-purchase more [4]. Note that this analysis leads us to predict an apparently paradoxical effect: that over-purchasing will be greater in those households that are most wealthy but also in those in which household income is falling.

Purpose of the present study and hypotheses

Here we report a test of the above account of over-purchasing using data collected in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic from two large population internet surveys conducted in different but economically comparable European countries–the UK and RoI–which, by design, administered parallel measures. Our hypotheses are:

First, that over-purchasing behaviour will be highly correlated across different groups of commodities; it should not be restricted to particular commodities. Hence, we predict that over-purchasing will be constitute a single latent trait that can be inferred from purchasing decisions about of a range of goods.

Second, that the following demographic and situational variables will be associated with over-purchasing: household income, loss of income due to the pandemic, having children at home, being infected by the virus, having a loved one who has been infected, distrust of neighbours, and paranoia. We also predict that over-purchasing will be associated with indices of psychological distress (depression, anxiety, specific anxiety about the COVID-19 virus) and also specific psychological variables likely to increase attention to scarcity cues: neuroticism, intolerance of uncertainty, and death anxiety.

Third, we predict that a greater sense of belonging to a neighbourhood, greater trust in neighbours, and greater capacity for analytic thinking/cognitive reflection will be negatively associated with over-purchasing.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

During the first phase of the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study, nationally representative surveys of the general adult populations of the UK (N = 2,025) and RoI (N = 1,041) were collected between the 23rd and 28th of March and between the 31st of March and 5th of April, 2020, respectively. The beginning of these periods corresponded with, in the UK, 52 days after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed and on the day that the UK Prime Minister announced a national lockdown at 8.30 in the evening and, in RoI, 31 days after the first confirmed case and two days after the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) announced a national lockdown. Data collection was conducted via the Internet by the survey company Qualtrics using stratified quota sampling to ensure that the sample characteristics of sex, age, and household income in the UK, and sex, age and geographical location in RoI, matched the respective populations. Therefore, these data were collected within the first week of the strictest physical distancing measures being enacted in both countries.

By design, the two surveys used comparable measures whenever possible. Inclusion criteria for both samples were that participants be aged 18 years or older at the time of the survey and be able to complete the survey in English. Median completion times were 28.91 and 37.52 minutes for the UK and Irish surveys respectively. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Sheffield and Ulster University. All particiapnts provided written informed consent. The basic sociodemographic characteristics for both samples are reported by [55] and summarised in S1 Table. Quality checks were carried out on the data and are detailed elsewhere [50].

Measures

Given the distinct socio-political contexts of the UK and Ireland, some variation existed in the measurement of the sociodemographic and political variables used in this study. All other variables were measured in an identical manner across the two samples.

Demographic and household characteristics

Self-reported gender and age were recorded, and age was also categorised into a 6-level variable for the regression analysis (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and 65+ years).

Number of adults in household: Participants were asked “How many adults (18 years or above) live in your household (including yourself)?” and were provided with options ranging from ‘1’ to ‘10 or more’.

Children: Participants were asked “How many children (below the age of 18) live in your household?” and were provided with options ranging from ‘0’ to ‘10 or more’. The scores were categorised into 4 groups (0, 1, 2, and 3 or more children).

Income was categorised into quintiles using relevant economic data from the two countries (see [56]): in the UK survey participants were asked “Please choose from the following options to indicate your approximate gross (before tax is taken away) household income in 2019 (last year). Include income from partners and other family members living with you and all kinds of earnings including salaries and benefits” to choose one of 5 categories: “£0 - £300 per week (equals about £0 - £1290 per month or £0–15,490 per year)”, “£301 - £490 per week (equals about £1,291 - £2,110 per month or £15,491 - £25,340 per year)”, “£491 - £740 per week (equals about £2,111 - £3,230 per month or £25,341 - £38,740 per year)”, “£741 - £1,111 per week (equals about £3,231 - £4,830 per month or £38,741 - £57,930 per year)”, and “£1,112 or more per week (equals about £4,831 or more per month or £57,931 or more per year)”. In the Irish survey participants were asked “Please choose from the following options to indicate your approximate gross (before tax is taken away) income in 2019 (last year)” and were provided with 10 categories: ‘0-€19,999’, ‘€20,000-€29,999’, ‘€30,000-€39,999’, ‘€40,000-€49,999’, ‘€50,000-€59,999’, ‘€60,000-€69,999’, ‘€70,000-€79,999’, ‘€80,000-€89,999’, ‘€90,000-€99,999’, and ‘€100,000 or more’; these 10 categories were collapsed into 5 categories to align with the UK data.

Perceived household income changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Respondents were provided with the following information, “Some people have lost income because of the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, for example because they have not been able to work as much or because business contracts have been cancelled or delayed. Please indicate whether your household has been affected in this way” and were provided three options: (1) My household has lost income because of the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, (2) My household has not lost income because of the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) I do not know whether my household has lost income because of the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. The last two categories were combined to produce a binary variable scored 1 = ‘My household has lost income’ and 0 = ‘My household has not lost income/do not know’.

Neighbourhood characteristics

Three questions taken from the UK Community Living Survey [57] were asked of respondents to assess their level of belongingness and trust in relation to their neighbourhood. Neighbourhood belongingness was measured using the question “How strongly do you feel you belong to your immediate neighbourhood?” (scored on a 4-point scale from 1 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘very strongly’). Neighbourhood trust was measured by summing the responses to two questions, (1) “How comfortable would you be with asking a neighbour to keep a set of keys to your home for emergencies” and (2) “How comfortable would you be asking a neighbour to collect a few shopping essentials for you, if you were ill and at home on your own” (both scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 ‘very uncomfortable’ to 4 ‘very comfortable’).

Over-purchasing

Participants were asked, “Please indicate the degree to which you have increased your purchasing of the following items in recent weeks because of the COVID-19 pandemic?” with nine items for: tinned foods, water, sanitary products (e.g. hand sanitiser), toilet roll, dried food (e.g. pasta, rice), bread, pharmacy products (e.g. painkillers, cold/flu products), batteries, and fuel (heating or car fuel). Response options were 1 ‘not at all’; 2 ‘very slightly’; 3 ‘moderately’; 4 ‘to a considerable degree’; and 5 ‘very considerably’.

Health and COVID-19 related variables

Health problems. Participants were asked “Do you have diabetes, lung disease, or heart disease?” and the response options were ‘Yes’ (1) and ‘No’ (0). They were also asked “Do any of your immediate family have diabetes, lung disease, or heart disease?” and the response options were ‘Yes’ (1) and ‘No’ (0).

Covid-19 status-self. Participants were asked “Have you been infected by the coronavirus COVID-19?” and seven responses were provided, which were collapsed into a binary variable representing ‘Perceived infection status—self’. Positive perceived infection status was based on the selection of either, ‘I have the symptoms of the COVID-19 virus and think I may have been infected’ or ‘I have been infected by the COVID-19 virus and this has been confirmed by a test’. Negative perceived infection status was based on the selection of either, ‘No. I have been tested for COVID-19 and the test was negative’, ‘No, I do not have any symptoms of COVID-19’, ‘I have a few symptoms of cold or flu but I do not think I am infected with the COVID-19 virus’, ‘I may have previously been infected by COVID-19 but this was not confirmed by a test and I have since recovered’ or ‘I was previously infected with COVID-19, this was confirmed by a test and I have now recovered’. Positive status (self) was coded ‘1’ and negative status coded as ‘0’.

Covid-19 status-other. Participants were also asked “Has someone close to you (a family member or friend) been infected by the coronavirus COVID-19?” and four responses were provided. These were collapsed into a binary variable representing ‘Perceived infection status–other’. Positive perceived infection status was based on the selection of either, ‘Someone close to me has symptoms, and I suspect that person has been infected’ or ‘Someone who is close to me has had a COVID-19 virus infection confirmed by a doctor’. Negative perceived infection status was based on the selection of either, ‘No’ or ‘Someone close to me has symptoms, but I am not sure if that person is infected’. Positive status (other) was coded ‘1’ and negative status coded as ‘0’.

Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection. Participants were asked to estimate their personal percentage risk of being infected with the COVID-19 virus in the next month. A slider was presented with ‘0’ and ‘100’ at the left and right hand extremes respectively, and the labels ‘No Risk’, ‘Moderate Risk’ and ‘Great Risk’ were shown on the left, middle and right-hand part of the scale respectively. This produced a continuous score ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting higher levels of perceived risk of being infected by COVID-19.

Psychological distress

Anxiety relating to COVID-19. Respondents’ degree of anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic was assessed using a single visual slider scale, ranging from 0 ‘not at all anxious’ on the left-hand side to 100 ‘extremely anxious’ on the right-hand side.

Depression. Nine symptoms of depression were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; [58]). Participants indicated how often they had experienced each symptom over the previous two weeks using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ‘Not at all’ to 3 ‘Nearly every day’. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicative of higher levels of depression. The psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 scores have been widely documented, and the reliability of the scale among the current sample was excellent in the UK (α = .92) and Ireland (α = .91). Scores of 10 or more indicate depression of ‘moderate’ severity [59].

Generalized anxiety. Symptoms of generalized anxiety were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7; [60]). Participants indicated how often they had experienced each symptom over the previous two weeks on a four-point Likert scale (0 ‘Not at all’ to 3 ‘Nearly every day’). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicative of higher levels of anxiety and scores of 10 or more indicating anxiety of moderate severity. The GAD-7 has been shown to produce reliable and valid scores in community studies [61] and the reliability in the current sample was excellent in both the UK (α = .94) and Ireland (α = .94).

Paranoia was measured using the brief five-item version [62] of the persecution subscale of the Persecution and Deservedness Scale [63]. Example items include “People will almost certainly lie to me” and “You should only trust yourself”. The scale scores had high reliability in the UK (α = .86) and Ireland (α = .83).

Personality

The Big-Five Inventory (BFI-10) [64] measures the ‘big five’ traits of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism widely found in studies of personality variation [65]. These traits correspond closely to five of the six traits assessed in the HEXACO model [17] assessed in two previous studies of over-purchasing [18, 19], the exception being honesty-humility. Each trait is measured by two items using a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’. Higher scores reflect higher levels of each personality trait, and Rammstedt and John [64] reported good reliability and validity for the BFI-10 scale scores.

Other psychological variables

Locus of control. The Locus of Control Scale (LoC) [66] measures internal (e.g., ‘My life is determined by my own actions’) and external locus of control. The latter has two components, ‘Chance’ (e.g., ‘To a great extent, my life is controlled by accidental happenings’) and ‘Powerful Others’ (e.g., ‘Getting what I want requires pleasing those people above me’). Each subscale was measured using three questions and a seven-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. Higher scores reflect higher levels of each construct. The scale scores had acceptable reliability in the UK (Chance, α = .70; Powerful Others, α = .85; Internality, α = .71) and Ireland (Chance, α = .63; Powerful Others, α = .78; Internality, α = .67).

Intolerance of uncertainty. Respondents’ intolerance of uncertainty, which is thought to play a key role in the aetiology and maintenance of worry, was assessed using the 12-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; [67]). The IUS was originally constructed to measure two factors, ‘unexpected events are negative and should be avoided’ measured by items such as ‘I always want to know what the future has in store for me’, and ‘uncertainty leads to the inability to act’ measured by items such as ‘the smallest doubt can stop me from acting’ [68]. Recent factor analytic research has shown that the IUS is best described by a bi-factor model, with a strong general factor being much more reliable than the specific factors, and hence unidimensional scoring is appropriate [69]. The scale had excellent reliability in the UK (α = .90) and RoI (α = .87).

Death Anxiety Inventory. Respondents’ attitudes towards death were assessed using the 17-item Death Anxiety Inventory (DAI, [70]), which measures four death-related anxiety factors (labelled as death acceptance, externally generated death anxiety, death finality, and thoughts about death) with items such as ‘I get upset when I am in a cemetery’, ‘The sight of a corpse deeply shocks me’, ‘I find it difficult to accept the idea that it all finishes with death’ and ‘I find it really difficult to accept that I have to die’. Responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘totally disagree’ to 5 ‘totally agree’. The scale had excellent reliability in the UK (α = .94) and Ireland (α = .92).

Right wing authoritarianism. The Very Short Authoritarianism Scale (VSA) [71] includes six items assessing agreement with statements such as: ‘It’s great that many young people today are prepared to defy authority’ (reverse-scored) and ‘What our country needs most is discipline, with everyone following our leaders in unity’. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of authoritarianism. The internal reliability of the scale scores in the Irish sample was lower than desirable (α = .58) but somewhat stronger for the UK sample (a = .65).

Analytical reasoning. The Cognitive Reflection Task of Analytical Reasoning (CRT) [53] is a three-item measure of analytical reasoning where respondents are asked to solve logical problems designed to stimulate intuitively appealing but incorrect responses. The response format was multiple choice with three foil answers (including the hinted incorrect answer), as recommended by [72].

Data analysis plan

Means and standard deviations for the over-purchasing items were produced and the differences between Ireland and the UK were tested using independent samples t-tests. The magnitudes of these differences were assessed using Cohen’s d estimates of effect size (d = 0.20 small effect, d = 0.50 medium effect, d = 0.80 a large effect). The main analysis was then conducted in three linked phases.

First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the over-purchasing data from Ireland and the UK separately. The number of factors to retain was based on the relative size of the sample eigenvalues and the 95 percentile eigenvalues from a parallel analysis with 500 replications. Models with 1 through to 3 factors were fitted, the parameters were estimated using robust maximum likelihood, and an oblique rotation (Geomin) was used for solutions with more than one factor.

The EFA of the over-purchasing items for both the UK and RoI strongly supported a unidimensional solution. The sample eigenvalues for the first three factors showed a very large first factor, and larger than the 95th percentile eigenvalues (in parentheses). In the UK: factor 1 = 6.335 (1.130); factor 2 = 0.763 (1.090), factor 3 = 0.384 (1.060); in Ireland, sample eigenvalues were as follows: factor 1 = 5.351 (1.185), factor 2 = 0.815 (1.127), factor 3 = 0.594 (1.084). These findings are strong evidence of a single latent trait of over-purchasing.

Second, a multi-group model was specified for the combined Irish and UK data, with the same factor structure (configural invariance) imposed and the factor loadings constrained to be equal across countries (metric invariance). The predictor variables were added, and the country-specific regression coefficients were estimated.

In the third phase, the between-group regression coefficients were tested for differences using the Wald test: if the coefficients were not significantly different, the paths were constrained to be equal; if they were significantly different, the coefficients were allowed to vary across groups. All of these analyses were conducted using latent variable modelling in Mplus 8.1 [73].

Results

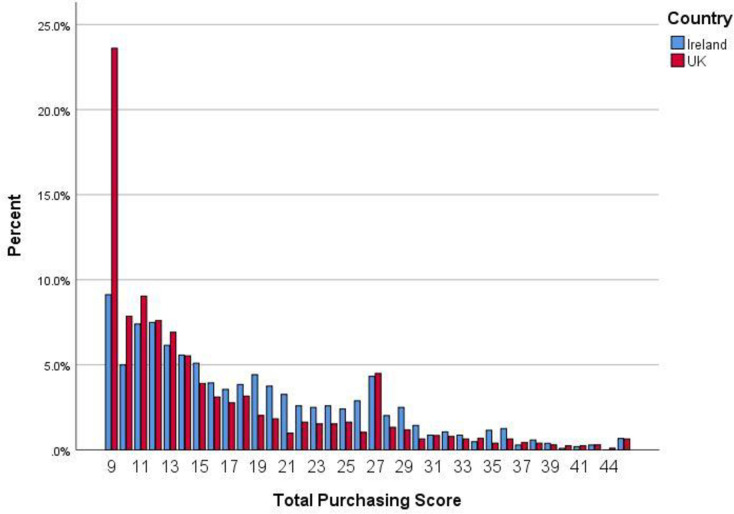

The distribution of total over-purchasing scores for the UK and RoI, are shown in Fig 2. Mean scores for the individual over-purchasing items together with tests for differences, are reported in Table 2. These data indicate that the highest rates of over-purchasing were reported by only a minority of both populations, with scores skewed towards the right end of the distribution. For example, in the UK sample, 23.6% recorded a score of 1 for all 9 items, indicating no over-purchasing at all, and this was the most common response; the corresponding figure for RoI was 9.1%. 70.3% of the UK sample had mean item scores of less than 2 (“very slightly), indicating very modest over-purchasing behaviour and the corresponding figure for RoI was 53.3%.

Fig 2. Distribution of over-purchasing in the UK and ROI during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Total scores on a 9-item scale with a minimum score of 9 and a maximum score of 45. Note: individual items were scored 1 ‘not at all’; 2 ‘very slightly’; 3 ‘moderately’; 4 ‘to a considerable degree’; and 5 ‘very considerably’. Hence, mean item scores of < 2 and mean total scores of < 18 imply little or no over-purchasing.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for panic buying items from Ireland and UK.

Mean item scores of < 2 imply little or no over-purchasing.

| Ireland N = 1041 | UK N = 2025 | t | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tinned food | 2.08 (1.10) | 2.01 (1.10) | 1.652 | .099 | .061 |

| Water | 1.90 (1.25) | 1.54 (1.03) | 8.586 | .000 | .328 |

| Sanitary products (hand sanitiser) | 2.68 (1.28) | 1.91 (1.13) | 17.036 | .000 | .650 |

| Toilet roll | 2.17 (1.18) | 1.96 (1.12) | 4.928 | .000 | .188 |

| Dried foods (e.g. pasta. rice) | 2.31 (1.17) | 2.00 (1.11) | 7.185 | .000 | .274 |

| Bread | 2.00 (1.15) | 1.79 (1.05) | 5.222 | .000 | .199 |

| Pharmacy products (e.g. painkillers, cold/flu products) | 2.02 (1.12) | 1.76 (1.03) | 6.608 | .000 | .252 |

| Batteries | 1.57 (0.98) | 1.42 (0.92) | 4.183 | .000 | .160 |

| Fuel (heating or car fuel) | 1.76 (1.07) | 1.49 (0.97) | 7.152 | .000 | .273 |

Note: df = 3064 for all t-tests

Scores were higher in RoI than the UK for all items, and these differences were significant with the single exception of tinned food. In absolute terms, however, these differences were generally not large (the exception being sanitary products) and the fact that they were statistically significant should be interpreted in the context of the large sample sizes. We also compared total purchasing scores for living location (city, n = 753; suburb, n = 760; town n = 918; and rural area, n = 635). There was a significant main effect, F(3, 3062) = 34.73, p < .001, although the effect size was small (h2 = .03). The mean total purchasing score was highest for people who described themselves as living in a city (mean = 19.28, SD = 9.25) and was significantly higher (Scheffe, P < .001) than for those who said they lived in a suburb (mean = 16.14, SD = 7.71), town (mean = 16.13, SD = 7.56) or rural area (mean = 15.43, SD = 6.97). No other pairwise differences were significant (all p > .05).

Zero-order correlations between factor scores, country-specific standardised regression coefficients and standardised regression coefficients, and Wald tests for the multi-group model as shown in Table 3. A complete correlation table showing relationships between all predictor variables is available in S2 Table. For the initial multi-group model, factor loadings were specified as invariant across the groups and the standardised factor loadings ranged from .645 to .789 and all were statistically significant (p < .001). The over-purchasing latent variable was regressed on the predictor variables, and the group-specific regression coefficients were estimated. As explained in the analysis plan, where significant differences existed in these coefficients for the two countries, coefficients are reported separately.

Table 3. Correlations and standardised regression coefficients for model of predictors of hoarding latent variable.

| Ireland | UK | Ireland | UK | Wald Δ Ire-UK | Multi-group estimates (Ireland/UK) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r | β | β | |||

| Age | -.282** | -.274*** | -.177*** | -.141*** | 0.660 | -.150*** |

| Gender (male) | .010 | .036 | .037 | .086*** | 2.031 | .074*** |

| Number adults | .097*** | .089*** | .041 | .031 | 0.020 | .027 |

| Number children | .167*** | .239*** | .076* | .065** | 0.002 | .069*** |

| Income | .046 | .006 | .066* | .052* | 0.685 | .059** |

| Lost income | .130** | .120*** | .055 | .024 | 0.648 | .033* |

| Neighbourhood belonging | -.005 | .121*** | .077* | .147*** | 3.708 | .127*** |

| Neighbourhood Trust | -.072* | -.039 | -.027 | -.034 | 0.045 | -.033 |

| Intolerance of Uncertainty | .244*** | .234*** | .021 | .007 | 0.095 | .014 |

| LOC: Chance | .187*** | .235*** | -.023 | -.040 | 0.154 | -.033 |

| LOC: Powerful Others | .114*** | .343*** | -.008 | .126*** | 4.136* | .005/.116*** |

| LOC: Internal | .111*** | -.041 | .011 | .034 | 0.295 | .023 |

| Paranoia | .370*** | .371*** | .194*** | .142*** | 1.132 | .162*** |

| Depression (>10) | .200*** | .282*** | .030 | .087** | 1.330 | .068** |

| Anxiety (>10) | .200*** | .244*** | -.002 | .024 | 0.262 | .017 |

| Extraversion | .001 | .083*** | .050 | .080*** | 0.720 | .070*** |

| Agreeableness | -.086*** | -.128*** | .048 | -.012 | 2.810 | .007 |

| Conscientiousness | -.149*** | -.196*** | -.062* | -.103*** | 1.204 | -.089*** |

| Neuroticism | .157*** | .108*** | -.010 | -.120*** | 6.692** | -.007/-.130*** |

| Openness | -.117*** | -.033 | -.076** | -.015 | 4.038* | -.082**/-.014 |

| Right Wing Authoritarianism | .136*** | .056* | .101*** | .044* | 3.200 | .062*** |

| Death Anxiety | .380*** | .407*** | .192*** | .210*** | 0.020 | .210*** |

| Cognitive Reflection Task | -.202*** | -.186*** | -.108*** | -.089*** | 0.561 | -.093*** |

| COVID-19 Anxiety | .140*** | .122*** | .029 | .009 | 0.252 | .014 |

| Health problems—self | .050 | .038 | .024 | .008 | 0.191 | .011 |

| Health problems—other | .124*** | .025 | .069* | .006 | 2.751 | .026 |

| Perceived infection status—self | .026 | .101*** | -.004 | .044* | 1.755 | 0.032 |

| Perceived infection status—other | .080** | .085*** | .018 | .025 | 0.054 | 0.022 |

| Personal Risk | .260** | .252*** | .120*** | .098*** | 0.275 | 0.107*** |

| R-square | .341*** | .364*** | .320***/.363*** | |||

| Adjusted R-square | .335 | .358 | .314/.357 |

Of the 23 variables specified in our model, all but six of the zero-order correlations were significant and in the direction expected in one or (in the majority) both countries; only one variable had a significantly opposite association to that predicted (internal locus of control was positively associated with over-purchasing in the Irish sample).

Many but not all of the final multi-group estimates also support our hypotheses, accounting for 36% (UK) and 32% (RoI) of the variance in over-purchasing. In this model, only neighbourhood belonging (in both countries) and neuroticism (in the UK) behaved contrary to expectation.

With respect to demographic variables, over-purchasing was associated with being younger, female, having children in the home, and having higher income but also with having lost income because of the pandemic. Contrary to expectation, health and infection status of self or others close to the self were not associated with over-purchasing, although a global measure of perceived risk of infection was. Although distrust of neighbours was not significant in the final model, the more general measure of paranoia was.

Of the psychological distress variables, only depression and death anxiety were significant in the multi-group model, although generalized anxiety and specific anxiety about the coronavirus were significant predictors when zero-order correlations were considered. Most likely this was a suppression effect caused by including multiple variables that included an anxiety component. This effect may also explain why neuroticism was negatively associated with over-purchasing in the UK in the multi-group model, despite being positively correlated with over-purchasing in both countries. There were also small effects for two of the other personality dimensions–extraversion and low conscientiousness.

Right wing authoritarianism was associated with over-purchasing, as expected, but the other psychological variables (the locus of control dimensions, intolerance of uncertainty) mostly failed to contribute to the multi-group model, despite being correlated with over-purchasing in the manner expected. Finally, as predicted, capacity for analytical reasoning (the CRT) was negatively associated with over-purchasing.

Discussion

We have proposed a psychological model of over-purchasing and panic buying, which was tested using large, nationally representative datasets from the UK and RoI collected in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive study of its kind, and the findings have the potential to inform policy in future national and international emergencies. The predictor variables included in our models were selected in light of the theoretical account of over-purchasing that we outlined in our introduction. However many were also consistent with previous speculation about the psychological factors involved in this phenomenon, such as personality and anxiety towards COVID-19 [12, 74, 75], but some had never before been considered in this context, for example death anxiety and analytical reasoning.

Substantial over-purchasing was reported by a minority of the participants across the two samples; about three quarters reported no or very little over-purchasing at all. This is consistent with evidence that stockouts during the early stages of the pandemic were driven by large numbers of consumers increasing their purchasing by modest amounts rather than a minority engaging in extreme levels of panic buying [3]. Nonetheless, we found strong evidence that over-purchasing is a coherent trait such that individuals who reported over-purchasing some items generally reported over-purchasing many items; a finding which is consistent with one of the few economic studies of panic buying [6]. Interestingly, toilet rolls were not subject to over-purchasing more than other commodities which suggests that over-purchasing is not related to disgust, as previously suggested [1]. The implication is that there must be one or more psychological processes that lead to a general tendency to purchase more than usual in times of crisis, which is consistent with our account that sees acquiring additional resources as a generalised and biologically adaptive response that is activated when the background rate–the availability of resources at reachable patches/supermarkets–is perceived to be falling rapidly.

We observed greater over-purchasing in RoI compared to the UK despite the fact that the two surveys were conducted at comparable stages in the pandemic, although, in absolute terms, these differences were generally not large (sanitary products being an exception). One possible explanation is that the government of Ireland took decisive action to contain the pandemic sooner than the UK government and, therefore, scarcity cues were more evident in that country when the surveys were conducted. In support of this, recent research has demonstrated that the timing of Government interventions are associated with panic buying, with earlier interventions coinciding with heightened rates of purchasing behaviours [76]. Commenting on differences between the nations, Irish historian Elaine Doyle was quoted in the UK’s Guardian newspaper [77]:

“While Boris [Johnson, the British Prime Minister] was telling the British people to wash their hands, our Taoiseach was closing the schools. While Cheltenham [a British horseracing festival] was going ahead, and over 250,000 people were gathering in what would have been a massive super-spreader event, Ireland had cancelled St Patrick’s Day,”

We also found that over-purchasing was more likely to be reported by people living in urban areas compared to those living suburbs, towns or rural areas. Whilst we did not make a prediction about this, one possible explanation is that scarcity cues (including the visible behaviour of other consumers) are more available in urban environments.

Based on our model, we made predictions about demographic, situational, and psychological variables that would either facilitate or inhibit over-purchasing by influencing either scarcity cues, perceived risk of infection, perceptions of the background rate (future scarcity), or the ability to over-purchase. Many but not all of our findings were consistent with our predictions. Consistent with previous economic research and foraging theory [6], we found that over-purchasing was associated with household income (presumably reflecting the opportunity afforded by having the necessary financial resources). However, it was also associated with loss of income due to the pandemic, which might at first seem paradoxical, but is clearly consistent with a psychological mechanism by which hoarding is provoked by fear of future scarcity. The number of adults in the household did not predict over-purchasing, but the number of children did, which we predicted on the basis that food-insecurity is a major source of anxiety for parents [42, 43].

Against expectation, health-related variables (whether or not individuals, or those close to them, had either been infected or were vulnerable because of health difficulties) did not influence over-purchasing much, although there was a strong association between over-purchasing and the perceived risk of being infected in the future. It is possible that the failure of the infection-status variables to predict was because these referred to whether or not individuals or those close to them had been infected in the past and, therefore, could not signal the likelihood of future scarcity whereas risk of infection, which referred to a possible future event, could. This was consistent with our foraging framework, as perceived risk of infection should lead to increased hoarding to reduce the number of shopping trips required and subsequently the risk to oneself [28].

Of our measures of psychological distress, depression most clearly predicted over-purchasing, as expected. Previous research has reported a modest effect for specific anxiety about the coronavirus [19] but, although zero-order correlations were found between over-purchasing and both our generalised anxiety measure and also our measure of anxiety about COVID-19, these were not evident in the final multi-group model. There was, however, a large effect for death anxiety.

The only two previous psychological studies of over-purchasing during the present pandemic that we are aware of focused on personality and reported conflicting results. One found that over-purchasing was inhibited by honesty-humility [17] (which we did not measure in this study, which began data collection before this finding was published), and hence prosociality, and the other did not find this effect [19]. These authors [19] also found that high conscientiousness was associated with over-purchasing whereas we found the opposite effect (which might be interpreted as conscientious people being more able to think through the long-term implications of their actions (i.e., that hoarding leads to scarcity), an account that would be consistent with our findings from the CRT), or that they were simply more complaint with advice not to purchase beyond their needs. Emotionality indirectly affected over-purchasing [19] whereas, in our study, neuroticism was positively associated with over-purchasing when zero-order correlations were considered, but negatively associated in the United Kingdom in the multi-group model (which we interpreted as a suppression effect). A reasonable conclusion, given these conflicting findings, is that there is, overall, not much evidence that the standard dimensions of personality play a large role in over-purchasing.

As predicted, over-purchasing was associated with right-wing authoritarianism, which manifests itself as increased sensitivity to threat and associated feelings of uncertainty [78, 79]. We have previously demonstrated that authoritarians are highly sensitive to the existential threat created by the COVID-19 pandemic; anxious authoritarians were found to be most likely to express nationalistic and anti-immigrant attitudes [52]. Hence, it appears that the stockpiling of essential items may serve as one way that authoritarians can bring order and security back into their lives.

One of our two predictions about inhibitors of over-purchasing was supported: in both countries over-purchasing was negatively associated with scores on an established measure of analytical reasoning [53]. Performance on this test and other measures of analytic reasoning have previously been associated with less willingness to believe in fake news or irrational beliefs such as conspiracy theories [80–82]. Our findings for trust, particularly in terms of relationships with neighbours, however, were at best mixed in relation to our hypotheses. On the one hand, as expected, paranoia—a measure of extreme distrust about the intentions of others—strongly predicted over-purchasing. This makes sense in the context of demand-side shortages when likelihood of scarcity is increased if other people act without regards to one’s own interests. On the other hand, specific trust of neighbours did not predict over-purchasing and, unexpectedly, a sense of belonging to a neighbourhood was positively associated with over-purchasing. One possibility is that people in highly cohesive neighbourhoods tend to shop in the same supermarkets and talk amongst themselves about the shortages they observe (that is, they provide each other with scarcity cues), which is consistent with the previously noted observation that over-purchasing occurred in areas of high population density. This interpretation is also supported by work demonstrating that observing neighbours engage in panic buying increases consumers’ own purchasing behaviours [15]. In future studies it will be interesting to investigate these variables in the context of supply-side shortages (for example, in the event of trade disruptions due to international disputes).

There are a number of strengths and limitations of this study. The major strength is that it is the most comprehensive study on this topic to date, which used high quality data collected from large and representative samples in two countries, collected early in the pandemic. We proposed and tested a psychological model of over-purchasing, which provides a framework for understanding how demographic, situational and psychological factors might exacerbate or mitigate over-purchasing behaviour. A limitation of the study is that one of the key concepts in the model–the perceived fall in the background rate (expectations about future scarcity)—was not directly measured, so the test was indirect. In future studies it will be important to include a variable in which people are asked to estimate the future likelihood of shortages, and also to ask people about their actual observations of news reports and empty supermarket shelves. Another weakness of the study mirrors one of its strengths–the large number of variables that were available to us. In future studies, it will be useful to refine our model to explicitly address the inter-relationships between the variables and the possibility that some (for example, the anxiety measures) are tapping a common latent process. Also, methods to avoid potential bias from the use of common methods (self-report) will be considered in studies. Finally, it would be important for future studies to test whether these findings extend to countries outside of Europe, including the global South and in populations that are not western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD; [83]).

Our model has implications for future crises. At a national level, governments, and at a local level, supermarket managers, should anticipate and seek to control over-purchasing by prohibiting bulk-buying, should manage scarcity cues in a way that reduces their salience (for example, by giving careful thought to the way that shelves are stocked), and should facilitate analytical reasoning; in their customers (for example, by providing detailed information about when dwindling stocks will be replaced). Our findings point to profiles of individuals who might be particularly vulnerable to over-purchasing, and who could either be reassured by appropriate policies–for example, by providing parents with young children special times when they can shop–or skilfully targeted messaging. Forward planning based on our model in preparation for future crises may lead to less panic-buying and less demand-side scarcity, and thereby may reduce the number of problems faced by governments during challenging times.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(SAV)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The initial stages of this project were supported by start-up funds from the University of Sheffield (Department of Psychology, the Sheffield Methods Institute and the Higher Education Innovation Fund via an Impact Acceleration grant administered by the university) and by the Faculty of Life and Health Sciences at Ulster University. The research was subsequently supported by the ESRC under grant number ES/V004379/1 and awarded to RPB, TKH, LL, JGM, MS, JM, OM, KB and LM. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jones L. What’s behind the great toilet roll grab? BBC News. 2020. March 26th Available from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52040532 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sim K, Chua HC, Vieta E, Fernandez G. The anatomy of panic buying related to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 288: 113015 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connell M, de Paula A, Smith K. Preparing for a pandemic: Spending dynamics and panic buying during the COVID-19 first wave. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2020. Available from https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/15100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jolly W. New data shows massive increases—and decreases—in consumer spending due to COVID-19. Savings.com.au [Internet]. 24th March2020. Available from: https://www.savings.com.au/credit-cards/new-data-shows-massive-increases-and-decreases-in-consumer-spending-due-to-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkes J. Has there always been panic buying? And when have people panic shopped through history? History Extra [Internet]. 7th May 2020. Available from: https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/toilet-paper-shortage-why-do-people-stockpile-panic-buying-history-rationing/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori M, Iwamoto K. The run on daily foods and goods after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. The Japanese Political Economy. 2014; 40: 69–113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honigsbaum M. Regulating the 1918–19 pandemic: Flu, stoicism and the Northcliffe press. Med Hist. 2013; 57: 165–85. 10.1017/mdh.2012.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding H. Rhetoric of a global epidemic: Transcultural communication about SARS. Carbondale, Ill: Southern Illinois Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savage DA. Towards a complex model of disaster behaviour. Disasters. 2019; 43: 771–98. 10.1111/disa.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA]. Food and water in an emergency. Jessup, MD: FEMA; 2004. Available from: https://www.fema.gov/pdf/library/f&web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas JA, Mora JA. Community resilience, latent resources and resourcescarcity after an earthquake: Is society really three mealsaway from anarchy? Nat Hazards. 2014; 74: 477–90. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeun KF, Wang X, Ma F, Li, KX. The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17: 3513 10.3390/ijerph17103513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Gentry JW. The behavioral responses to perceived scarcity–the case of fast fashion. Int Rev Retail Distrib. 2016; 26: 260–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheu J-B, Kuo H-T. Dual speculative hoarding: A wholesaler-retailer channel behavioral phenomenon behind potential natural hazard threats. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020; 44: 101430 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng R, Shou B, Yang J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega. 2020. 10.1016/j.omega.2020.102238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterman JD, Dogan G. “I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here.” Behavioral causes of phantom ordering in supply chains. J Oper Manag. 2015; 39–40: 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K, Ashton MC. The HEXACO personality factors in the indigenous personality lexicons of English and 11 other languages. J Pers. 2008; 76: 1001–54. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Columbus S. Who hoards? Honesty-humility and behavioural responses to the 2019/20 coronavirus pandemic. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. 2020. Available from https://psyarxiv.com/8e62v/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garbe L, Rau R, Toppe T. Influence of perceived threat of Covid-19 and HEXACO personality traits on toilet paper stockpiling. Plos One. 2020; 15: e0234232 10.1371/journal.pone.0234232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charnov EL. Optimal foraging, the marginal value theorem. Theor Popul Biol. 1976; 9: 129–36. 10.1016/0040-5809(76)90040-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turrin C, Fagan NA, Dal Monte O, Chang SWC. Social resource foraging is guided by the principles of the Marginal Value Theorem. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 11274 10.1038/s41598-017-11763-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Addicott MA, Pearson JM, Sweitzer MM, Barack DL, Platt ML. A primer on foraging and the explore/exploit trade-off for psychiatry research. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017; 42: 1931–9. 10.1038/npp.2017.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith EA, Bettinger RL, Bishop CA, Blundell V, Cashdan E, Casimir MJ, et al. Anthropological applications of optimal foraging theory: A critical review. Curr Anthropol. 1983; 24: 625–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JE. The gravity model. Annu Rev Econom. 2011; 3: 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huff DL. Defining and estimating a trading area. J Mark. 1964; 28: 34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson PL, Dominguez F, Teklehaimanot S, Lee MH, Brown AR, Goodchild M. Does distance decay modelling of supermarket accessibility predict fruit and vegetable intake by individuals in a large metropolitan area? J Health Care Poor Undeserved 2013; 24: 172–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens DW, Krebs JR. Foraging theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickins TE, Schalz S. Food shopping under risk and uncertainty. Learn Motiv. 2020; 72: 101681 10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabay AS, Apps MAJ. Foraging optimally in social neuroscience: Computations and methodological considerations. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2020. nsaa037 10.1093/scan/nsaa037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anselme P, Güntürkün O. How foraging works: Uncertainty magnifies food-seeking motivation. Behav Brain Sci. 2019; 42: 1–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vander Wall SB. Food hoarding in animals. Chicago Ill: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laran J, Salerno A. Life-history strategy, food choice, and caloric consumption. Psychol Sci. 2013; 24: 167–73. 10.1177/0956797612450033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nettle D, Andrews C, Bateson M. Food insecurity as a driver of obesity in humans: The insurance hypothesis. Behav Brain Sci. 2017; 40: e105 10.1017/S0140525X16000947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyengar S, Simon A. News coverage of the Gulf Crisis and public opinion: A study of agenda-setting, priming and framing. Commun Res. 1993; 20: 365–83. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo M, Sun S, Merolla AJ, Zhang S. Willingness to help following the Sichuan Earthquake: Modeling the effects of media involvement, stress, trust, and relational resources Commun Res. 2011; 39: 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Photopoulos J. A scientist’s opinion: Interview with Dr. Dimitrios Tsivrikos about consumer behaviour during COVID-19. European Science-Media Hub [Internet]. 30th April 2020. Available from: https://sciencemediahub.eu/2020/04/30/a-scientists-opinion-interview-with-dr-dimitrios-tsivrikos-about-consumer-behaviour-during-covid-19/. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chadwick J. Pandemic psychologist explains by people panic-buy toilet roll. Daily Mail. 27th March 2020. Available from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-8160043/Pandemic-psychologist-explains-people-panic-buy-toilet-roll.html [Google Scholar]

- 38.BBC. Coronavirus: Shoppers told to buy responsibly. BBC News. 21st March 2020. Available from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51989721 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton R, Thompson D, Bone S, Chaplin LN, Griskevicius V, Goldsmith K, et al. The effects of scarcity on consumer decision journeys. J Acad Mark Sci. 2019; 47: 532–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker JR, Lehmann DR. When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. J Retail. 2011; 87: 142–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor M, Stevens GJ, Agho KE, Raphael B. The impact of household financial stress, resilience, social support, and other adversities on the psychological distress of Western Sydney parents. Int J Popul Res. 2017; 2017: e6310683 10.1155/2017/6310683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knowles M, Rabinowich J, de Cuba SE, Cutts DB, Chilton M. “Do you wanna breathe or eat?”: Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Matern Chil Health J. 2015; 20: 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006; 118: e859–e68. 10.1542/peds.2006-0239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elahi A, McIntyre JC, Hampson C, Bodycote H, Sitko K, Bentall RP. Home is where you hang your hat: Host town identity, but not hometown identity, protects against mental health symptoms associated with financial stress. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2018; 37: 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McElroy E, McIntyre JC, Bentall RP, Wilson T, Holt K, Kullu C, et al. Mental health, deprivation, and the neighbourhood social environment: A network analysis. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019; 7: 719–34. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenow JK, Constantino SM, Daw ND, Phelps EA. Chronic and acute stress promote overexploitation in serial decision making. J Neurosci. 2017; 37: 5681–9. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3618-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tackett JL, Lahey BB. Neuroticism. In: Widiger TA, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shapiro DH, Schwartz CE, Astin JA. Controlling ourselves, controlling our world: Psychology’s role in understanding positive and negative consequences of seeking and gaining control. Am Psychol. 1996; 51: 1213–30. 10.1037//0003-066x.51.12.1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carleton RN, Sharpe D, Admundson GJG. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty: Requisites of the fundamental fears? Behav Res Ther. 2007; 45: 2307–16. 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iverach L, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014; 34: 580–93. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duckitt J, Sibley CG. Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. J Pers. 2010; 78: 1861–93. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartman TK, Stocks TVA, McKay R, Gibson-Miller J, Levita L, Martinez A, et al. The authoritarian dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2021. 10.1177/1948550620978023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frederick S. Cognitive reflection and decision making. J Econ Perspect. 2005; 19: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toplak ME, West RF, Stanovich KE. Assessing miserly information processing: An expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Think Reason. 2014; 20: 147–68. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy J, Vallieres F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Communs. 2021; 12: 29 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McBride O, Murphy J, Shevlin M, Gibson-Miller J, Hartman TK, Hyland P, et al. Monitoring the psychological, social, and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the popualtion: Context, design, and conduct of the longitudinal COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2020; e1861 10.1002/mpr.1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harper R, Kelly M. Measuring social capital in the United Kingdom. London: Office for National Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kroenke K, Spitzer R. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002; 32: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012; 184: E191–E6. 10.1503/cmaj.110829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166: 1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hinz A, Klien AM, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. J Affect Disord. 2017; 210: 338–44. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McIntyre JC, Wickham S, Barr B, Bentall RP. Social identity and psychosis: Associations and psychological mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. 2018; 44: 681–90. 10.1093/schbul/sbx110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Melo S, Corcoran R, Bentall RP. The Persecution and Deservedness Scale. Psychol Psychother. 2009; 82: 247–60. 10.1348/147608308X398337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007; 41: 203–12. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sapp SG, Harrod WJ. Reliability and validity of a brief version of Levenson's locus of control scale. Psychol Rep. 1993; 72: 539–50. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buhr K, Dugas MJ. The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behav Res Ther. 2002; 40: 931–45. 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00092-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Birrell J, Meares K, Wilkinson A, Freeston M. Toward a definition of intolerance of uncertainty: A review of factor analytical studies of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011; 31: 1198–208. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hale W, Richmond M, Bennett J, Berzins T, Fields A, Weber D, et al. Resolving uncertainty about the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12: Application of modern psychometric strategies. J Pers Assess. 2016; 98: 200–8. 10.1080/00223891.2015.1070355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tomás-Sábado J, Gómez-Benito J, Limonero J. The Death Anxiety Inventory: A revision. Psychol Rep. 2005; 97: 793–6. 10.2466/pr0.97.3.793-796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bizumic B, Duckitt J. Investigating right wing authoritarianism with a Very Short Authoritarianism scale. J Soc Political Psychol. 2018; 6: 129–50. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sirota M, Juanchich M. Effect of response format on cognitive reflection: Validating a two and four-option multiple choice question version of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Behav Res Method. 2018; 50: 2511–22. 10.3758/s13428-018-1029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide (8th ed). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cypryańska M, Nezlek JB. Anxiety as a mediator of relationships between perceptions of the threat of COVID-19 and coping behaviors during the onset of the pandemic in Poland. Plos One. 2020; 15: e0241464 10.1371/journal.pone.0241464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jaspal R, Lopes B, Lopes P. Predicting social distancing and compulsive buying behaviours in response to COVID-19 in a United Kingdom sample. Cogent Psychol. 2020; 7: 1 10.1080/23311908.2020.1800924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prentice C, Chen J, Stantic B. Timed intervention in COVID-19 panic buying. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020; 57: 102203 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.David N, Carroll R. Experts divided over comparison of UK and Ireland's coronavirus records. Guardian. 13th April 2020. Available from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/experts-divided-comparison-uk-ireland-coronavirus-record [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feldman S, Stenner K. Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychol. 1997; 18: 741–70. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stenner K. The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bronstein MV, Pennycook G, Bear A, Rand DG, Cannon TD. Belief in fake news is associated with delusionality, dogmatism, religious fundamentalism, and reduced analytic thinking. J Appl Res Mem Cogn. 2019; 8: 108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pennycook G, Cheyne JA, Seli P, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA. Analytic cognitive style predicts religious and paranormal belief. Cognition. 2012; 123: 335–46. 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Swami V, Voracek M, Stieger S, Tran US, Furnham A. Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition. 2014; 133: 572–85. 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rad MS, Martingano AJ, Ginges J. Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population. PNAS. 2018; 115: 11401–5. 10.1073/pnas.1721165115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]