Abstract

Background & Aims:

The Ile138Met variant (rs738409) in the PNPLA3 gene has the largest effect on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), increasing the risk of progression to severe forms of liver disease. It remains unknown if the variant plays a role in age of NAFLD onset. We aimed to determine if rs738409 impacts on the age of NAFLD diagnosis.

Methods:

We applied a novel natural language processing (NLP) algorithm to a longitudinal electronic health records (EHR) dataset of >27,000 individuals with genetic data from a multi-ethnic biobank, defining NAFLD cases (n = 1,703) and confirming controls (n = 8,119). We conducted i) a survival analysis to determine if age at diagnosis differed by rs738409 genotype, ii) a receiver operating characteristics analysis to assess the utility of the rs738409 genotype in discriminating NAFLD cases from controls, and iii) a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) between rs738409 and 10,095 EHR-derived disease diagnoses.

Results:

The PNPLA3 G risk allele was associated with: i) earlier age of NAFLD diagnosis, with the strongest effect in Hispanics (hazard ratio 1.33; 95% CI 1.15–1.53; p <0.0001) among whom a NAFLD diagnosis was 15% more likely in risk allele carriers vs. non-carriers; ii) increased NAFLD risk (odds ratio 1.61; 95% CI 1.349–1.73; p <0.0001), with a strongest effect among Hispanics (odds ratio 1.43; 95% CI 1.28–1.59; p <0.0001); iii) additional liver diseases in a PheWAS (p <4.95 × 10−6) where the risk variant also associated with earlier age of diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Given the role of the rs738409 in NAFLD diagnosis age, our results suggest that stratifying risk within populations known to have an enhanced risk of liver disease, such as Hispanic carriers of the rs738409 variant, would be effective in earlier identification of those who would benefit most from early NAFLD prevention and treatment strategies.

Lay summary:

Despite clear associations between the PNPLA3 rs738409 variant and elevated risk of progression from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to more severe forms of liver disease, it remains unknown if PNPLA3 rs738409 plays a role in the age of NAFLD onset. Herein, we found that this risk variant is associated with an earlier age of NAFLD and other liver disease diagnoses; an observation most pronounced in Hispanic Americans. We conclude that PNPLA3 rs738409 could be used to better understand liver disease risk within vulnerable populations and identify patients that may benefit from early prevention strategies.

Keywords: NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, PNPLA3, Natural language processing, Electronic health record, Phenome-wide association study, PheWAS, Genetic, Survival, Biobank, Hispanic

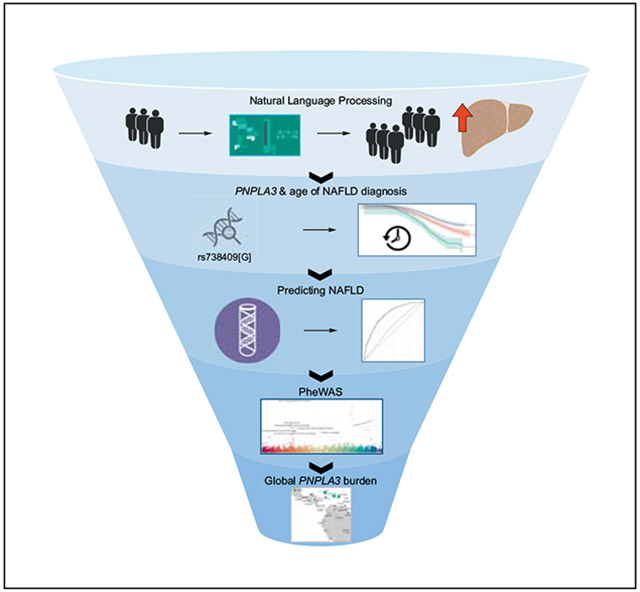

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is estimated to impact 24% of the global population and is a leading impetus for liver transplantation, representing over 75% of all chronic liver disease.1,2 In the United States, the prevalence of NAFLD has steadily increased over the last 3 decades, and to date, population estimates range from 30-45%.3,4 NAFLD is characterized by a continuum of severity, ranging from simple steatosis, a relatively benign condition, to fibrosis and hepatocyte death. Up to 30% of histologically defined cases of NAFLD include inflammation and can lead to higher rates of liver-related death.5 NAFLD may progress to steatohepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but the etiologies of these progressions are complex and poorly understood.

To date, through genome-wide association study (GWAS) discoveries, more than 10 variants have been significantly associated with NAFLD. Of these, a coding variant in PNPLA3 (patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3) p.Ile138Met (rs738409 C>G) is the strongest genetic risk factor for NAFLD and its severity, with odds ratios (ORs) ranging from 2.08 to 18.23 (combined OR 3.41; 95% CI 2.57–4.52; p <0.00001)6-9 across different populations. PNPLA3 encodes a protein belonging to the patatin-like phospholipase family with putative triglyceride and phospholipid remodeling functions within hepatic lipid deposits.10 The rs738409 polymorphism has been repeatedly associated with NAFLD risk and elevated liver fat content,7-9 presumably through the variant’s putative functional role in reducing hepatic triglyceride hydrolytic activity by nearly 80%.11,12

The PNPLA3 “G” risk allele has a frequency of 23.1% in the general population (NHLBI TopMed; n = 125,568). However, the risk allele is more common in Hispanic/Latino (HA) populations (47.16%; 95% CI 47.1–47.2)7,13,14 than in African American (AA 13.7%) and European American (EA 22.8%) populations,15 and has a larger impact on NAFLD risk in HA populations.7,9 This may contribute, in part, to a higher estimated prevalence of NAFLD in HA (45–58%), compared to AA (24–35%) and EA (33–44%),3,4 and supports previous findings that HA are more likely to progress to more severe forms of liver disease than other ancestries.16 Despite clear associations of PNPLA3 rs738409 with elevated risk of progression from NAFLD to more severe forms of liver disease,17,18 particularly among HA, it remains unknown if PNPLA3 rs738409 plays a role in age of NAFLD onset. This is likely due to the asymptomatic nature of NAFLD and a general lack of longitudinal population cohorts for which genetic information is available. To prevent the progression of NAFLD to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and other more severe pathologies, it is critical to better classify the onset of NAFLD. Early screening for NAFLD within populations with high genetic (or other) risk could lead to more focused prevention, interventions and/or treatments.

To address this knowledge gap and clinical need, we leveraged large-scale, longitudinal electronic health record (EHR) information, sequencing data and novel natural language processing (NLP) techniques to determine the effect of PNPLA3 rs738409 on age at disease diagnosis in a diverse ancestry population of over 27,000 individuals. To gain insight into potentially novel variant-disease associations, we performed a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) to unselectively examine the relationship of the PNPLA3 rs738409 variant with a broad spectrum of EHR-derived health outcomes. Our findings contribute to the understanding of the impact of PNPLA3 rs738409 on liver disease progression, and highlight a pronounced disease risk in HA populations.

Patients and methods

Participants

Mount Sinai’s BioMe is an EHR-linked clinical care biobank and comprises over 50,000 multi-ethnic participants (as of June, 2019), characterized by a broad spectrum of longitudinal biomedical traits. Enrolled participants consent to be followed throughout their clinical care (past, present, and future) in real-time, allowing integration of their genomic information with their de-identified EHR data for discovery research and clinical care implementation. BioMe is an unselected population-based biobank, and participants are predominantly recruited from outpatient primary care practice. EHR adoption began in 2006, and all outpatient clinics are linked to EHRs. The present study population is comprised of 27,744 AA, HA and EA participants from BioMe for whom EHR clinical measures and genetic data were available (Fig. S1). The BioMe Biobank is IRB approved and fully complies with Health Information Privacy and Portability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Genetic data

The BioMe biobank is a longitudinal cohort allowing for analysis of time course data from the EHR that is linked to genetic data. Genetic data for 31,676 BioMe biobank participants, was obtained through a collaboration with the Regeneron Genetics Center. All samples were tested for sufficient DNA concentrations by picogreen-based quantification, and processed with Kapa library prep reagents, the IDT xGen capture platform, and genotyped on the Illumina Global Screening Array. Samples were blacklisted for gender discordance (genotype sex-check results with homozygosity rates more than 0.2 but less than 0.8 were excluded), low sequencing coverage, heterozygosity rates (samples falling outside of 3 standard deviations from the mean were excluded), contamination, low call rate and the discovery of duplicates. Variants were removed for excessive missingness (>3%). Finally, pairwise identity by descent (IBD) levels were checked and individuals from the pairs with IBD greater than 0.185 were removed. The p.Ile138Met variant (rs738409 C>G) on chromosome 22 in PNPLA3 was extracted from all participants passing QC filters (n = 31,676).

In the total population, the frequency of the (G) risk allele was 25.5% with frequencies in self-identified HA, AA and EA of 35%, 14.4% and 23.1%, respectively, consistent with prior reports for global,15 EA and AA populations.7 HA participants in BioMe in New York City are predominantly of Caribbean origin, which likely explains why the G allele frequency is lower compared to frequencies reported in other HA populations of predominantly Mexican descent (~50%).7,13,19,20 The rs738409 variant was tested for Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using a χ2 test prior to analysis. Within AA and EA genotype distributions were in HWE (AA χ2 p = 0.31, EA χ2 p = 0.61), while the HA genotype distribution violated HWE (χ2 p = 1.6 × 10−5). Observations were similar among the control (non-NAFLD) population (AA G = 14.1%, χ2 p = 0.36; EA G = 22.7%, χ2 p = 0.4; HA G = 34.1%, χ2 p = 0.0002). Given the high accuracy of the genotyping, it is unlikely that violation of HWE is due to technical error. HA controls had similar genotype frequencies, indicating that the HWE violation is unlikely to be the primary cause of any association with NAFLD, and we proceeded with the analysis of the variant.21 Our final data set was restricted to AA, HA and EA participants (n = 27,744).

Phenotypic data from electronic health records

For this study, age was defined as age at enrollment in the biobank and was restricted to >18 years. Anthropometry measures and serum lab values for alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, platelets, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin (markers commonly used in the diagnosis of liver diseases) were available in a subset of participants (Table S1). For all continuous measures other than age (i.e. body mass index (BMI), lab values), we generated a median value of all outpatient measures on record for a given participant, excluding emergency and inpatient measures.

We used NLP methods to query EHR medical charts and imaging reports for terminology indicating a diagnosis of NAFLD, an approach that has been shown to improve sensitivity and overall accuracy of case definition. Details of the NLP approach including its validation are published elsewhere.22 Briefly, we used CLiX, a general-purpose stochastic parser (Clinithink, Atlanta, USA), which maps patient facts described in clinical narrative to post-coordinated SNOMED expressions. SNOMED expressions are based on SNOMED CT, a hierarchical, general-purpose clinical terminology (SNOWMED International, London, UK). We used the NLP engine to map SNOMED concepts for NAFLD (including concepts such as steatosis, NAFLD etc.) for individual patients. The algorithm was iterated and improved using manual validation as the gold standard. Two clinicians, without knowing case/control status, independently reviewed all records on 200 patients; 100 case patients identified as having NAFLD and 100 randomly selected patients identified as controls. Patients were classified as cases or controls based on clinical criteria. A clinical diagnosis of NAFLD required i) the presence of fatty infiltration of the liver on imaging or physician documentation in the notes that such imaging was performed/diagnosis was confirmed, ii) exclusion of hepatitis C infection, iii) absence of documented alcohol abuse. Inter-rater agreement was high (kappa = 0.95) and disagreements were reviewed by consensus in consultation with a third clinician. Further details are provided elsewhere.22 This approach significantly improved sensitivity (93% vs. 32%) compared to ICD codes. We identified 2,228 cases (compared to 893 with ICD). Similarly, we used NLP to classify controls from EHR who had radiology imaging of the liver, but with confirmed absence of excess liver fat or steatosis (n = 9,886). We then used ICD codes to remove participants with a diagnosis of hepatitis B or C from cases and controls, resulting in 1,703 NAFLD cases and 8,119 screened controls available for analyses (Fig. S1). Age at diagnosis, represented in years from birth, was determined by subtracting participant date of birth from the first disease diagnosis date on record.

Statistical analyses

Population characteristics

Unadjusted means for age, sex, BMI and lab values are reported in Table S1. Linear regression of PNPLA3 rs738409 on traits adjusted for age, sex and 6 ancestry principal components was performed and p values represent the effect of each G risk allele. Unadjusted means for age, sex, BMI and lab values were stratified by NAFLD status and a 2-sided Cochran independent t test was used to test for differences (adjusted for age, sex and 6 principal components) between cases and controls in all participants and individual ancestry groups. p values for age are from chi-square test (Table S2). To examine the role of PNPLA3 rs738409 on NAFLD diagnosis, logistic regression was used to estimate ORs with Wald CIs and p values for the G risk allele in adjusted (age, sex, BMI and 6 principal components) and unadjusted models.

Survival analyses

We leveraged the availability of longitudinal EHR data to further characterize the clinical impact of the PNPLA3 p.Ile138Met genotype on NAFLD diagnosis. We conducted a survival analysis to determine if age at diagnosis differed by PNPLA3 genotype using computed product-limit estimates of the survivor function and Kaplan-Meier survival curves to visualize results. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the additive effect of the PNPLA3 risk allele on the hazard age of diagnosis for NAFLD. NLP-defined NAFLD cases (n = 1,703) were analyzed with screened controls (n = 8,119). The first record indicating a diagnosis was considered the “event”, while undiagnosed controls were censored upon reaching current age. In survival analyses, the Log-rank test (χ2, p value) was used to test for homogeneity in age at diagnosis survival functions for NAFLD. The Sidák test for multiple pairwise comparisons was used for comparison of age at diagnosis across genotype strata, with Hall-Wellner confidence intervals. Cox proportional hazards models (adjusted for age, sex and 6 principal components) generated hazard ratios with confidence limits. Following the PheWAS analysis (see below), we conducted similar survival analyses to determine if age at diagnosis for ICD9-derived phenome wide significant diseases differed by PNPLA3 genotype. In these analyses, all individuals without ICD9 codes for a given disease were considered controls.

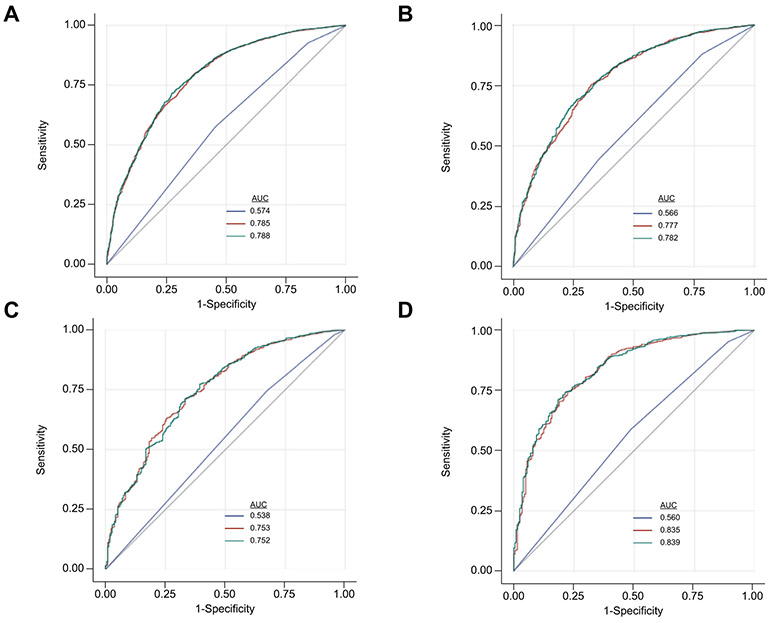

Prediction analyses

We used receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses to assess the utility of common clinical measures (age, sex, BMI and “lab values”: ALT, AST, albumin, platelets, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin) and PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype as predictors to discriminate between NAFLD cases and controls.23 Lab values were not normally distributed and were log10 transformed. Importantly, all data used for NAFLD cases in ROC models were obtained prior to the first diagnosis. These analyses were carried out using cases (n = 1,095) for whom BMI and laboratory values were available prior to the first diagnosis date. For controls, we used data values from the time of enrollment in the BioMe biobank. Area under the curve (AUC) values for ROC are presented with 95% Wald confidence limits and ROC contrast estimation tests were used to assess improvements in disease discrimination between i) PNPLA3 genotype, ii) Age + sex + BMI + 6 Principal components + “lab values”, iii) Age + sex + BMI + 6 Principal components + PNPLA3 genotype and iv) a full model containing all predictors; Age + sex + BMI + 6 Principal components + “lab values” + PNPLA3 genotype.

In addition, we used net reclassification improvement (NRI) to assess changes in predicted risks between models among NAFLD cases and controls.24 The NRI analysis evaluates the net number (%) of individuals correctly reclassified as “events/cases” or “nonevents/controls” when using the disease predictor groups described above. Integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) analysis was used to compare prediction models and to assess improvement in average sensitivity.24 Absolute IDI is dependent on the overall “event” rate. Since the NAFLD event-rates in our cohort are relatively small, the absolute IDI value will be small. Therefore, we report relative IDI values, which represent a percent relative improvement between models. Survival, ROC, NRI and IDI analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4/SAS Studio 3.8.

Phenome-wide association study

We used a linear mixed model25 to perform PheWAS association between PNPLA3 rs738409 and 10,095 EHR-derived ICD-9 codes. Cases for a given disease were defined as having one or more relevant ICD-9 codes on record. PheWAS analyses were conducted using the GCTA software via the “–mlma" flag, adjusting for sex encoded as a discrete covariate, as well as age, BMI, and the first 6 eigenvectors of principal components encoded as continuous covariates. A linear mixed model in GCTA was chosen for the PheWAS analysis as this method has been shown to best account for population structure and distant relatedness as well as case:control imbalances typical to diverse biobank study populations.26 To control for relatedness, a genetic relationship matrix (GRM) was calculated across all 31,676 participants from 281,666 common (minor allele frequency [MAF] >1%), non-palindromic single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Both the GRM and principal components were calculated using the GCTA software using the “–make-grm.gz” and “–pca", flags respectively. For visualization purposes, ICD9 coding structure was used to group individual ICD9 codes into 17 broad clinical disease categories, derived from the ICD-9 codes. Of the 10,095 EHR-derived ICD-9 codes, 7,846 intersected with available genetic information, thus the Bonferroni corrected significance threshold was p <6.37 × 10−6. Naïve ORs, for the impact of PNPLA3 rs738409 “G”, are based on unadjusted case:control counts. Cramer’s V statistic was used to test for correlation between the most significant ICD9 codes among risk allele carriers and a matrix of the top ICD9 phenotype hits across all individuals was generated to visualize disease co-occurrence.

Using the PheWAS methods described above, we also tested for associations in 2 additional sets of EHR-derived procedure codes. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are a proprietary coding system developed by the American Medical Association to code services provided by health care professionals.27 Similarly, ICD9 Procedure codes represent medically billable procedures, a separate classification system from diagnosis codes.28 We conducted procedure-wide association studies on 12,302 CPT codes and 5,721 ICD9 procedure codes within the participants. Of the 12,302 CPT codes and 5,721 ICD9 procedure codes, 4,391 and 2,227 intersected with available genetic information, thus the Bonferroni corrected significance thresholds were p <1.13 × 10−5 and p <2.25 × 10−5, respectively.

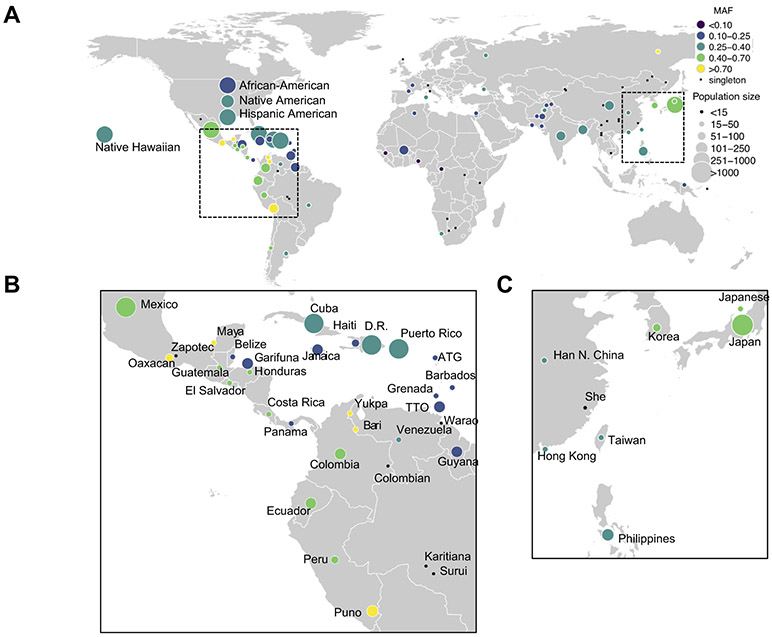

Global PNPLA3 rs738409 frequencies

We examined risk allele frequency of rs738409 within the multi-ethnic PAGE Study, which includes 45,255 unrelated participants from across the Americas, Africa, East and South Asia, and Oceania.29 As part of the PAGE Study, 99 distinct populations were assembled, based on self-identified race or ethnicity or country of origin (Sorokin, Belbin, Wojcik et al., 2019) within PAGE (n = 38 labels), the Human Genome Diversity Panel populations (n = 53 labels), and additional global reference panels from within the PAGE Study (n = 8 labels). We also assembled a super-population label for self-identified Hispanics. Allele frequencies for the rs738409 G allele were calculated using PLINK 1.90.30 Frequencies were visualized in R using the maps (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/maps/maps.pdf) and plotrix (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/plotrix/plotrix.pdf) packages.

Results

PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and NAFLD diagnosis

To determine whether PNPLA3 rs738409 influenced the age at which NAFLD was diagnosed, we conducted survival analyses on our longitudinal EHR data. Notably, our novel NLP methods improved true NAFLD case identification by 150%, increasing the number of cases from 893 (with ICD alone) to 2,228 and accurately defined 9,986 NAFLD-free controls. Among these individuals, the PNPLA3 G risk allele was associated with earlier age of NAFLD diagnosis in all participants (hazard ratio [HR] 1.49; 95% CI 1.35–1.64; p <0.0001) (Fig. 1A) and the mean age of diagnosis in carriers of both risk alleles was 3.1 years earlier than in non-carriers (58.4 years vs. 55.3 years). This corresponds to a 5% greater probability of being diagnosed with NAFLD at age 60 among carriers of both risk alleles compared to non-carriers (18% vs. 13%, respectively). In individual ancestry groups the overall effect of the PNPLA3 G risk allele on NAFLD diagnosis age was similar (HA: HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.15–1.53, p <0.0001; AA: HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.23–1.85, p <0.0001; EA: HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.08–1.65, p = 0.005). However, the probability of being diagnosed with NAFLD by age 60 was 15% higher in HA carriers of both risk alleles compared to non-carriers (31% vs. 16%, respectively). Results were similar for AA (28% vs. 10% non-carriers) and EA (23% vs. 12% non-carriers) (Fig. 1B,C). Consistent with what others have shown, PNPLA3 G risk allele carriers had an increased risk of NAFLD compared to non-risk carriers (OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.349–1.73; p <0.0001), which was somewhat attenuated after adjusting for age, sex, BMI and 6 principal components (OR 1.48; 95% CI 1.35–1.60; p <0.0001). The effect of PNPLA3 was more pronounced among HA (OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.28–1.59; p <0.0001) and EA (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.27–1.80; p <0.0001) than among AA (OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.16–1.77; p = 0.0008).

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing age at diagnosis for NAFLD by PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype.

(A) All, (B) HA, (C) AA and (D) EA. X-axis displays the number of years to NAFLD diagnosis (age of diagnosis). Y-axis displays the Kaplan-Meier survival probability by genotype. G is the effect allele; CC (blue curve); GC (red curve); and GG (green curve). The log-rank p value denotes the strength of significant differences among survival curves. Symbols denote p-values from Sidak-adjusted log-rank multiple comparisons: †significantly difference from CC (p <0.0001), ‡significantly difference from CC (p <0.01), #significantly difference from GC (p = 0.001). Shaded areas represent confidence intervals. Censoring marks have been removed for visualization. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Prediction of NAFLD

To assess whether PNPLA3 genotype can be used to predict risk of developing NAFLD, we compared its predictive ability to that of clinical measures (BMI, age, sex, principal components and measurable components of blood such as ALT and AST) for which we had data before the NAFLD diagnosis. PNPLA3 had a limited ability as a sole predictor of NAFLD (AUROC = 0.574) (Table S3). The use of clinical measures alone yielded a higher NAFLD discriminatory ability (AUROC = 0.785) than PNPLA3 alone, and improved sensitivity by 34%. When PNPLA3 was added to clinical measures, NAFLD discrimination improved marginally (AUROC = 0.788, p <0.0001) (Fig. 2), and resulted in 19% of controls being correctly reclassified (p <0.0001), but only 1% of cases correctly reclassified (Table S4). When stratified by ancestry, PNPLA3 had the strongest individual AUC in HA (AUROC = 0.566) and improved NAFLD prediction when added to clinical measures in HA, however the effect was modest (AUC 0.777 vs. 0.782, p = 0.03) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3). Similarly, the addition of PNPLA3 to clinical measures in HA correctly reclassified 13% of cases (p = 0.001) and accounted for a 2.2% increase in sensitivity over clinical measures alone (Tables S4 and S5). PNPLA3 did not significantly improve prediction of NAFLD over clinical measures in AA or EA, nor did it improve the percent of cases correctly classified or improve sensitivity. The full model containing clinical measures and PNPLA3 performed best in EA compared to HA and AA (Table S3).

Fig. 2. Receiver operating characteristic curves for disease discrimination.

AUROC for 3 models on NAFLD by ancestry: Blue line = PNPLA3 genotype; Red line = age, sex, 6 principal components, BMI and “lab values”; Green line = age, sex, 6 principal components, BMI, “lab values” and PNPLA3 genotype. (A) all participants (956 NAFLD, 7,248 control), (B) African American (214 NAFLD, 2,392 control), (C) Hispanic (540 NAFLD, 3,279 control), (D) European American (210 NAFLD, 1,577 control). 95% Wald confidence limits and ROC contrast estimation test p values for NAFLD are presented in Fig. S2. BMI, body mass index; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Clinical characterization of PNPLA3 risk allele status using electronic health records

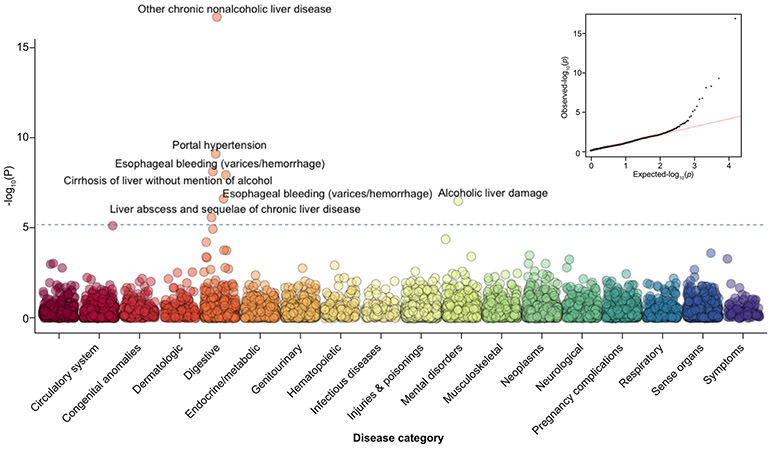

In order to explore the broader clinical impact and comorbidities of the PNPLA3 risk allele, we performed a PheWAS to correlate ICD9 codes with PNPLA3 risk allele status in the BioMe biobank participants. As anticipated, the PNPLA3 risk allele was most significantly associated with “Other chronic non-alcoholic liver disease” [ICD9: 571.8](β = 0.01/per allele [±0.002]; p = 1.91 × 10−17), a sub-classification of the broader category “diseases of the digestive system” (Fig. 3). It is used to describe fatty liver without mention of alcohol (NAFLD), but can also serve as a diagnosis code for NASH.31 Additional liver or liver-related diseases also reached significance, including “portal hypertension” [ICD9: 572.3] (β = 0.008 [±0.001]; p = 7.43 × 10−10), “non-alcoholic cirrhosis“ [ICD9:571.5] (β = 0.01 [±0.002]; p = 1.1 × 10−8) “esophageal varices“ [ICD9: 456.21] (β = 0.006 [±0.001]; p = 2.34 × 10−7), “alcoholic cirrhosis“ [ICD9: 571.2] (β = 0.005 [±0.001]; p = 3.1 × 10−7) and “other chronic liver disease“ [ICD9: 572.8] (β = 0.0048 [±0.001]; p = 2.56 × 10−6) (Table 1). PheWAS analyses adjusted for BMI did not notably change association results for NAFLD or the other top phenotypes (Fig. S3, Table S6). NLP-defined NAFLD had a low correlation and co-occurrence with other ICD9-defined liver diseases (Figs. S4 and S5). To assess whether our PheWAS findings were influenced by the fact that NAFLD cases may more often be affected by related diseases, we performed sensitivity analyses in which we removed all NAFLD cases. This attenuated disease associations (Table S6), but liver phenotype hierarchy was maintained. We observed a significant association of one ICD9 procedure code (42.33: Endoscopic excision) with PNPLA3 (Tables S7 and S8).

Fig. 3. PheWAS Manhattan plot of PNPLA3 Ile138Met vs. ICD9 diagnosis codes.

The x-axis represents categories of disease as defined by ICD9 coding hierarchy. The y-axis is the −log10 p value for the association. Adjustment for age, sex, PCs 1-6. Bonferroni significance for multiple testing was p <6.37 × 10−6. PheWAS, phenome-wide association study.

Table 1.

Top 15 PheWAS ICD9 phenotypes for PNPLA3 rs738409 (adjusted for age, sex and principle components).

| ICD-9 | Beta | Standard error | Odds ratio | p value | Description | Organ system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 571.8 | 0.0160 | 0.0019 | 1.66 | 1.91E-17 | Other chronic non-alcoholic liver disease | Digestive |

| 572.3 | 0.0084 | 0.0014 | 1.65 | 7.43E-10 | Portal hypertension | Digestive |

| 456.1 | 0.0072 | 0.0012 | 1.69 | 7.18E-09 | Esophageal varices without mention of bleeding | Digestive |

| 571.5 | 0.0125 | 0.0022 | 1.34 | 1.10E-08 | Cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol | Digestive |

| 456.21 | 0.0063 | 0.0012 | 1.61 | 2.34E-07 | Esophageal varices, without bleeding, elsewhere | Digestive |

| 571.2 | 0.0050 | 0.0010 | 1.91 | 3.10E-07 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver | Mental disorders |

| 572.8 | 0.0048 | 0.0010 | 1.58 | 2.52E-06 | Other sequelae of chronic liver disease | Digestive |

| 456.8 | 0.0033 | 0.0007 | 1.90 | 7.26E-06 | Varices of other sites | Circulatory system |

| 789.59 | 0.0061 | 0.0014 | 1.37 | 1.11E-05 | Other ascites | Digestive |

| 303.9 | 0.0056 | 0.0014 | 1.30 | 4.12E-05 | Alcohol dependence, unspecified drinking behavior | Mental disorders |

| 573.8 | 0.0048 | 0.0012 | 1.30 | 5.91E-05 | Other specified disorders of liver | Digestive |

| 456.2 | 0.0026 | 0.0007 | 1.88 | 0.00017 | Esophageal, with bleeding | Digestive |

| 537.89 | 0.0068 | 0.0018 | 1.29 | 0.00017 | Other specified disorders of stomach and duodenum | Digestive |

| 369.69 | 0.0007 | 0.0002 | 3.15 | 0.00024 | One eye: profound vision impairment; other eye: normal vision | Sense organs |

| 141.90 | 0.0012 | 0.0003 | 2.73 | 0.00031 | Malignant neoplasm of tongue, unspecified | Neoplasms |

| 571.1 | 0.0019 | 0.0005 | 1.89 | 0.00037 | Acute alcoholic hepatitis | Mental disorders |

| 794.80 | 0.0050 | 0.0014 | 1.32 | 0.00039 | Non-specific abnormal results of function study of liver | Digestive |

| 572.4 | 0.0020 | 0.0006 | 1.74 | 0.00043 | Hepatorenal syndrome | Digestive |

| 790.6 | 0.0097 | 0.0028 | 1.13 | 0.00050 | Other abnormal blood chemistry | Symptoms |

Shaded cells represent phenome-wide significant hits (p <6.37 × 10 −6). Naïve odds ratios, for the impact of PNPLA3 rs738409 “G”, are based on case:control counts. PheWAS, phenome-wide association study.

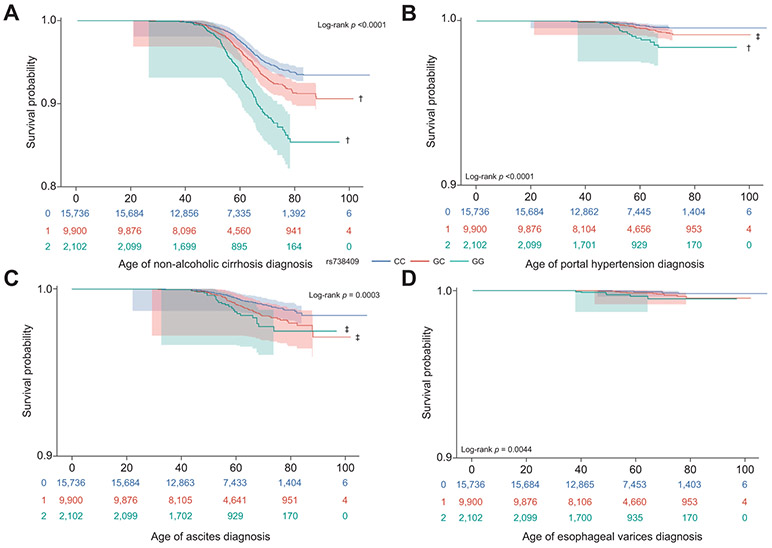

Impact of PNPLA3 Ile138Met genotype on age of diagnosis in PheWAS identified liver diseases

To gain insight into a potentially novel role for PNPLA3 in the diagnosis of additional liver diseases, we performed survival analyses for 4 conditions that reached significance in our PheWAS. The PNPLA3 risk allele was significantly associated with earlier age of diagnosis in all participants for “non-alcoholic cirrhosis” [ICD9: 571.5] (HR 1.35; 95% CI 1.22–1.49; p <0.0001) and “portal hypertension” [ICD9: 572.3] (HR 1.52; 95% CI 1.12–2.08; p = 0.007) (Fig. 4A,B), with carriers of both risk alleles being diagnosed 1 year earlier than non-carriers. The diagnostic age of “esophageal varices” [ICD9: 456.21], although significantly associated with PNPLA3 in PheWAS, was not impacted by the PNPLA3 risk allele (HR = 1.69; 95% CI 0.98–2.89; p = 0.055) which may be due to a small number of cases for this disease. Interestingly, age of diagnosis for “ascites” [ICD9: 789.59], which was sub-phenome wide significant, was earlier in carriers of the G allele for PNPLA3 (HR 1.29; 95% CI 1.04–1.61; p = 0.01) (Fig. 4C,D). Consistent with our observations in NAFLD, stratification of nonalcoholic cirrhosis cases by ancestry showed PNPLA3 genotype to be associated with earlier age of diagnosis in HA (HR 1.42; 1.26–1.62; p <0.0001) and AA (HR 1.42; 1.1–1.82; p = 0.005), but not in EA. Analyses for other diseases were not stratified by ancestry due to sample size.

Fig. 4. Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing time to diagnosis for ICD9-defined liver diseases.

(A) non-alcoholic cirrhosis (571.5, n = 941), (B) portal hypertension (572.3, n = 92), (C) ascites (789.59, n = 201) and (D) esophageal varices (456.21, n = 31). X-axis displays the number of years to NAFLD diagnosis (age of diagnosis). Y-axis displays the Kaplan-Meier survival probability by genotype and has been adjusted to visualize results due to high percentage of censoring. G is the effect allele; CC (blue curve); GC (red curve); and GG (green curve). The log-rank p value denotes the strength of significant differences among survival curves. Symbols denote p values from Sidak-adjusted log-rank multiple comparisons: †significantly different from CC (p <0.0001); ‡significantly different from CC (p <0.01). Shaded areas represent confidence intervals. Censoring marks have been removed for visualization. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Frequency of PNPLA3 risk variant worldwide

Understanding that the PNPLA3 risk variant plays a role in susceptibility to and progression of NAFLD, we sought to investigate which global populations may be at a heightened genetic risk. We examined patterns of segregation of the rs738409[G] allele within the PAGE Study, which represents global diversity across the Americas, Africa, East Asia, Oceania, and South Asia.29 The G allele segregated commonly (MAF >0.05), within all populations of the PAGE Study with exception of 2 HGDP populations, Mbuti Pygmy and Melanesians, where the variant was monomorphic (MAF 0%; 95% CI 0–16.0%, in both populations) (Fig. 5 and Table S9). The G allele segregated at highest frequencies within PAGE Global reference populations from Central and South America, notably the Warao (MAF 85.0%; 95% CI 64.0–94.8%), Puno (MAF 85.4%; 95% CI 81.7–88.5%), Zapotec (MAF 85.7%; 95% CI 68.5–94.3%), and Bari, where the variant was fixed (MAF 100%; 95% CI 89.8–100%). The G variant was the major allele in PAGE populations from Central and South America, including Peru (MAF 66.7%; 95% CI 58.8–73.7%), El Salvador (MAF 60.8%; 95% CI 49.4–71.1%), Guatemala (MAF 58.3%; 95% CI 46.8–69.0%), Ecuador (MAF 54.1%; 95% CI 49.7–58.6%) and Mexico (MAF 49.9%; 95% CI 48.9–50.8%). In a super-population of self-identified Hispanics from the PAGE Study, the variant also segregated commonly (MAF 39.6%; 95% CI 39.2–40.1%). Elsewhere in PAGE, the variant segregated commonly in populations of East Asian ancestry, notably Japan (MAF 45.7%; 95% CI 44.4–46.9%), Korea (MAF 45.1%; 95% CI 36.5–53.9%), and China (MAF 35.5%; 95% CI 30.5–40.8%). Geographical regions within Central and South America, as well as South Eastern Asia show enrichment for the PNPLA3 G allele, which is consistent with population-based epidemiological studies demonstrating a heightened prevalence of NAFLD in individuals with these genetic back-grounds.2,6,19 This data illustrates how populations currently under represented in PNPLA3 research may also be impacted by the risk variant.

Fig. 5. Global allele frequency of PNPLA3 rs738409 in the populations of the PAGE study.

(A) Global allele frequencies for the minor and risk allele (G allele) are shown. (B) Enlarged image of Central and South America from panel A. (C) Enlarged image of East Asia from panel A. Color denotes allele frequency and size denotes the number of individuals in each of 99 populations from PAGE.

Discussion

Using longitudinal HER data, collected for more than 10 years, and NLP approaches, we retrospectively defined NAFLD cases and controls in the multi-ethnic BioMe Biobank in New York City. We found evidence to show that individuals who carried the PNPLA3 p.Ile138Met (rs738409) G variant, a known NAFLD-associated disease allele, had a significantly earlier age of NAFLD diagnosis. The effect of rs738409 on the age of diagnosis of NAFLD was most pronounced in the HA population, among whom the prevalence of NAFLD is also highest.3,20 However, our results show AA carriers of the PNPLA3 risk allele, a population thought to have a lower prevalence of chronic liver disease (3.9 vs. 6.7% in AA and HA, respectively), also incur risk for NAFLD and other liver diseases.32 This observation is consistent with a prior report in which the rs738409 polymorphism conferred high risk for NAFLD and NASH development across ethnicities.9 Consequently, our findings provide the first evidence for a role of PNPLA3 p.Ile138Met in the timing of progression to NAFLD.

NAFLD is the most common cause (52%) of chronic liver disease across ancestries32 and populations at heightened risk, such as HA and AA,33 encounter disparities in the prevalence and treatment of liver disease34 which could have clinically meaningful consequences on liver-related morbidity and mortality in these populations.34 NAFLD is often asymptomatic and is in many cases not diagnosed until ~40 years, yet the disease is becoming increasingly prevalent in HA children and adolescents, with NAFLD diagnosis occurring as early as 8 years.2 NAFLD commonly progresses to other, more severe liver pathologies5 and an early NAFLD diagnosis identifies individuals at risk of more severe liver disease in adulthood. Early phase animal studies have provided intriguing evidence for a causal role of PNPLA3 in the progression of NAFLD to NASH,35,36 suggesting translational therapies could be developed to mitigate progression to NASH in at-risk populations. Therefore, identifying NAFLD earlier in at-risk populations is an important first step. This need highlights the importance of enhanced understanding of the role of PNPLA3 rs738409 in the timing of NAFLD development.

Although PNPLA3 had strong associations with age of NAFLD diagnosis in our study, and is a well-established risk variant for NAFLD, its ability to discriminate NAFLD cases from controls alone was limited compared to clinical measures. Prediction of NAFLD marginally improved when PNPLA3 genotype data was added to clinical measures, but this modest improvement was only observed in HA participants at a magnitude similar to prior work in an HA population for which the rs738409 risk allele also had a modest impact in discriminating NAFLD.37 Currently, genetic testing is not clinically recommended in the diagnosis of NAFLD.38 Yet, there are clear associations of PNPLA3 with disease severity and, as we now show, with age of diagnosis. Our global analysis of PNPLA3 rs738409 risk allele frequency revealed enrichment of the variant in several ancestries localizing to Central/South America and South/East Asia. This suggests that individuals with ancestral ties to these locations are at an elevated risk for NAFLD, a concept consistent with GWASs findings showing strong association between rs738409 and NAFLD risk in Hispanic, Japanese and Korean individuals.6,7,39,40 Our data suggests that PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype could be combined with commonly measured clinical data present in the EHR (BMI, liver enzymes) to target individuals at increased risk of liver disease and more accurately stratify disease risk in a clinical setting. This approach could aid in earlier clinical prevention strategies, namely before the onset of liver disease, within existing health care populations and improve identification of individuals at risk of developing NAFLD and/or other chronic liver diseases.

We showed that PNPLA3 was most significantly associated with NAFLD in a PheWAS of our cohort, consistent with prior GWASs in NAFLD showing strong associations with rs738409.6-8 Additionally, we identified phenome-wide significant associations with portal hypertension, esophageal varices, non-alcoholic cirrhosis, and alcoholic cirrhosis; all known sequelae of chronic liver disease. NAFLD is thought to represent the proximal end of a spectrum of liver disease and severity, and it is common for patients with more severe forms of liver disease such as NASH and cirrhosis to first present with NAFLD.3 The PNPLA3 rs738409 G allele has previously been associated with increased risk of cirrhosis (with ORs ranging from 2.08 to 3.41),17,41 portal hypertension and esophageal varices (in the context of NAFLD or cirrhosis severity, respectively).42,43 PNPLA3 rs738409 may be directly impacting on the risk of other chronic liver diseases, however the associations may also be explained by the role of PNPLA3 rs738409 on enhancing the risk for NAFLD, which greatly increases the probability of progressing to more severe disease.

Additionally, we show evidence of PNPLA3 rs738409 associating with earlier ages of liver disease diagnosis identified through PheWAS, suggesting potential independent effects of the variant and justifying a closer examination of the biological role of the variant in more severe aspects of liver disease. In addition to being associated with liver diseases, PNPLA3 rs738409 has been reported to play a role in lipoprotein metabolism, liver enzyme levels and dietary energy balance, suggesting a potential pleiotropic role in liver disease.7,44,45 It is premature to assume that PNPLA3 rs738409 directly contributes to other liver diseases independently of NAFLD. But, the application of further PheWAS to other variants identified in NAFLD GWASs (i.e. NCAN, PPP1R3B, GCKR and LYPLAL1)8,37 could potentially further inform biological connections between NAFLD and other liver diseases and contribute to our understanding of how NAFLD progresses to more severe pathologies.

The overall prevalence of NAFLD in our cohort was below general population level estimates, despite NLP methods utilizing radiological imaging. Had all individuals had radiology data, NAFLD prevalence would likely be higher. The low observed prevalence suggests that [a] NAFLD is under diagnosed and/or [b] ICD9 codes used for the determination of a disease phenotype can be incomplete and cases in our cohort were “missed”46,47 which may, in part, explain why there is a generally low co-occurrence of NAFLD with other liver diseases. Recently, a large meta analysis reported that the global prevalence of NAFLD (55.5%) in older patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is 2-fold higher than in the general population and T2D appears to accelerate the progression to NASH.48 Given the overall prevalence of T2D (28%) and obesity (35%) in our study population, a higher prevalence of NAFLD was expected. This further illustrates the critical need to assess NAFLD risk factors, such as PNPLA3 genotype and T2D status in younger populations as an approach to slow or prevent progression to NASH. Despite a lower than expected NAFLD prevalence, we were able to show a clear pattern of genetic effects on age of diagnosis for a variety of liver diseases. Similarly, several novel interesting sub-phenome wide significant threshold diseases, whose non-significance may simply be limited by power, were identified. Our prediction analyses were tempered by the availability of pre-diagnosis predictor variable data and reduced case sizes, yet we still show some predictive utility of PNPLA3 and other clinical measures. Replication of our findings in younger populations would further clarify the role of PNPLA3 rs738409 in age of liver disease diagnoses.

By leveraging longitudinal EHR data, we showed that PNPLA3 rs738409 contributes to an earlier diagnosis of NAFLD and several other liver diseases. Our findings suggest that PNPLA3 rs738409 could be used to stratify risk within populations known to have an enhanced risk for liver disease, an approach that may help identify those who would benefit most from early prevention and/or treatment strategies. A PheWAS approach to our data contributed to enhanced understanding of the relationship between clinical phenotypes and PNPLA3 rs738409 and these new associations may help improve our understanding of the underlying PNPLA3 rs738409 biology. Similar disparities in disease risk have been observed in AA populations, in which risk variants for APOL1 are both more frequent and confer increased risk of kidney disease, cardiovascular disease and early-onset hypertension.49,50 Ancestry-specific disparities such as these highlight the need for a greater understanding of how PNPLA3 p.Ile138Met impacts the timing of NAFLD development and, more broadly, the strong need for diversity in translational genomic research focusing on clinically relevant variants. Overall, approaches like ours can be used to identify at-risk populations within a health care network. Leveraging genetic variants to predict disease is an area of intense study in personalized medicine,51 yet other critical components such as ethnicity, clinical measures, environmental factors and family history must be considered in risk-stratification approaches. Disease prediction begins to have meaningful clinical utility only when treatment(s) exists.52 NAFLD currently has no standard clinical treatment recommendations beyond general diet counseling and weight loss, which have had some success,53 however the pre-identification of individuals most at risk of developing NAFLD and related liver disease would allow clinicians to target those poised to benefit the most from these approaches. Due to the pervasiveness of pediatric obesity, most overweight and obese children should be screened for NAFLD. Hispanic populations exhibit an elevated frequency of the PNPLA3 rs738409 variant, which also seems to have a stronger impact in this population, coupled with earlier ages of diagnosis. Although the variant showed an effect in other ethnic groups, specific attention must be paid to Hispanic children and adolescents. Our findings suggest that attempts to stratify NAFLD risk in younger age groups, and intervene accordingly, may contribute to mitigating negative medical outcomes in adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Natural language processing increased NAFLD detection over ICD codes by 2.5 times.

rs738409 “GG” carriers were diagnosed with NAFLD 3 years earlier than non-carriers.

PNPLA3 rs738409 effects were most pronounced in Hispanics.

PheWAS showed rs738409 was associated with other NAFLD-related liver diseases.

rs738409 was associated with earlier diagnosis for PheWAS-identified diseases.

Acknowledgements

R.W.W. was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (P30ES023515) at the time of this study. E.E.K., N.S.A-H. and G.M.B. are supported by the National Institutes of Health; National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) (U01 HG009610). E.E.K, and C.R.G. are supported by NHGRI (R01 HG010297, U01 HG009080) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (R01 HL104608). E.E.K. is also supported by the NIMHD (UM1 HG0089001, U01 HG007417), the (NHLBI) (X01 HL1345), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney and Digestive Disease (R01 DK110113). C.R.G. is also supported by the NIH (R56HG010297). R.J.F.L. is supported by the NIH (U01 HG007417; R01 DK110113; R56HG010297; X01 HL134588; R01 DK107786; R01 HL142302; R01 DK075787). We would like to thank participants of the BioMe Biobank for their permission to use their health and genomic information. We acknowledge a collaboration with Regeneron Genetics Center, who performed genotyping in BioMe. (Regeneron Genetics Center had no input as to the design and conduct of the study; the interpretation of the data; preparation or review of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.)

Financial support

Sources of author financial support were not involved in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- AA

African American

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUC

area under the curve

- BMI

body mass index

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- EA

European American

- EHR

electronic health record

- GRM

genetic relationship matrix

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- HA

Hispanic/Latino

- HR

hazar ratio

- HWE

Hardy Weinberg equilibrium

- IBD

identity by descent

- IDI

integrated discrimination improvement

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NLP

natural language processing

- NRI

net reclassification improvement

- OR

odds ratios

- PheWAS

phenome-wide association study

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.01.029.

References

- [1].Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9(6):524–530.e1. quiz e560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, et al. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 2004;40(6):1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 2011;140(1):124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34(3):274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kawaguchi T, Sumida Y, Umemura A, Matsuo K, Takahashi M, Takamura T, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of the human PNPLA3 gene are strongly associated with severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Japanese. PLoS One 2012;7(6):e38322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2008;40(12):1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, Hernaez R, Kim LJ, Palmer CD, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet 2011;7(3):e1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xu R, Tao A, Zhang S, Deng Y, Chen G. Association between patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) polymorphisms and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a HuGE review and meta-analysis. Scientific Rep 2015;5:9284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mitsche MA, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 promotes transfer of essential fatty acids from triglycerides to phospholipids in hepatic lipid droplets. J Biol Chem 2018;293(18):6958–6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Smagris E, BasuRay S, Li J, Huang Y, Lai KM, Gromada J, et al. Pnpla3I148M knockin mice accumulate PNPLA3 on lipid droplets and develop hepatic steatosis. Hepatology 2015;61(1):108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang Y, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Expression and characterization of a PNPLA3 protein isoform (I148M) associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 2011;286(43):37085–37093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Edelman D, Kalia H, Delio M, Alani M, Krishnamurthy K, Abd M, et al. Genetic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease within a Caribbean-Hispanic population. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2015;3(6):558–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goran MI, Walker R, Le KA, Mahurkar S, Vikman S, Davis JN, et al. Effects of PNPLA3 on liver fat and metabolic profile in Hispanic children and adolescents. Diabetes 2010;59(12):3127–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes. bioRxiv 2019:531210. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Carrion AF, Ghanta R, Carrasquillo O, Martin P. Chronic liver disease in the Hispanic population of the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9(10):834–841. quiz e109-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trepo E, Gustot T, Degre D, Lemmers A, Verset L, Demetter P, et al. Common polymorphism in the PNPLA3/adiponutrin gene confers higher risk of cirrhosis and liver damage in alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2011;55(4):906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Trepo E, Nahon P, Bontempi G, Valenti L, Falleti E, Nischalke HD, et al. Association between the PNPLA3 (rs738409 C>G) variant and hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Hepatology 2014;59(6):2170–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fleischman MW, Budoff M, Zeb I, Li D, Foster T. NAFLD prevalence differs among hispanic subgroups: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20(17):4987–4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lazo M, Bilal U, Perez-Escamilla R. Epidemiology of NAFLD and type 2 diabetes: health disparities among persons of hispanic origin. Curr Diabetes Rep 2015;15(12):116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Deng HW, Chen WM, Recker RR. Population admixture: detection by Hardy-Weinberg test and its quantitative effects on linkage-disequilibrium methods for localizing genes underlying complex traits. Genetics 2001;157(2):885–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Van Vleck TT, Chan L, Coca SG, Craven CK, Do R, Ellis SB, et al. Augmented intelligence with natural language processing applied to electronic health records for identifying patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease at risk for disease progression. Int J Med Inform 2019;129:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, D'Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27(2):157–172. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Denny JC, Bastarache L, Ritchie MD, Carroll RJ, Zink R, Mosley JD, et al. Systematic comparison of phenome-wide association study of electronic medical record data and genome-wide association study data. Nat Bio-technol 2013;31(12):1102–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Belbin GM, Odgis J, Sorokin EP, Yee MC, Kohli S, Glicksberg BS, et al. Genetic identification of a common collagen disease in puerto ricans via identity-by-descent mapping in a health system. eLife 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].AMA. Principles of CPT® Coding. Ninth ed. American Medical Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elixhauser A, CA S. Hospital inpatient statistics, 1996 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Research Note. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; (AHCPR Pub. No. 99-0034); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wojcik GL, Graff M, Nishimura KK, Tao R, Haessler J, Gignoux CR, et al. Genetic analyses of diverse populations improves discovery for complex traits. Nature 2019;570(7762):514–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Alkaline Software. The Web’s Free ICD-9-CM Medical Coding Reference. icd9data.com. 2006. Available from: http://www.icd9data.com/2013/Volume1/520-579/570-579/571/571.8.htm. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Setiawan VW, Stram DO, Porcel J, Lu SC, Le Marchand L, Noureddin M. Prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis by underlying cause in understudied ethnic groups: the multiethnic cohort. Hepatology 2016;64(6):1969–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Flores YN, Yee HF Jr, Leng M, Escarce JJ, Bastani R, Salmeron J, et al. Risk factors for chronic liver disease in Blacks, Mexican Americans, and Whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999-2004. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103(9):2231–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nguyen GC, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Racial disparities in the management of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension: a national study. Hepatology 2007;45(5):1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Linden D, Ahnmark A, Pingitore P, Ciociola E, Ahlstedt I, Andreasson AC, et al. Pnpla3 silencing with antisense oligonucleotides ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis in Pnpla3 I148M knock-in mice. Mol Metab 2019;22:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Colombo M, Pelusi S. Towards precision medicine in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with PNPLA3 as a therapeutic target. Gastroenterology 2019;157(4):1156–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Walker RW, Sinatra F, Hartiala J, Weigensberg M, Spruijt-Metz D, Alderete TL, et al. Genetic and clinical markers of elevated liver fat content in overweight and obese Hispanic children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(12):E790–E797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 2016;59(6):1121–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kitamoto T, Kitamoto A, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Ochi H, Nakamura T, et al. Genome-wide scan revealed that polymorphisms in the PNPLA3, SAMM50, and PARVB genes are associated with development and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Japan. Hum Genet 2013;132(7):783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chung GE, Lee Y, Yim JY, Choe EK, Kwak MS, Yang JI, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and SAMM50 are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Korean population. Gut Liver 2018;12(3):316–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shen JH, Li YL, Li D, Wang NN, Jing L, Huang YH. The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. J Lipid Res 2015;56(1):167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rotman Y, Koh C, Zmuda JM, Kleiner DE, Liang TJ. The association of genetic variability in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010;52(3):894–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].King LY, Johnson KB, Zheng H, Wei L, Gudewicz T, Hoshida Y, et al. Host genetics predict clinical deterioration in HCV-related cirrhosis. PLoS One 2014;9(12):e114747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kollerits B, Coassin S, Beckmann ND, Teumer A, Kiechl S, Doring A, et al. Genetic evidence for a role of adiponutrin in the metabolism of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18(23):4669–4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Huang Y, He S, Li JZ, Seo YK, Osborne TF, Cohen JC, et al. A feed-forward loop amplifies nutritional regulation of PNPLA3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(17):7892–7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cronin RM, Field JR, Bradford Y, Shaffer CM, Carroll RJ, Mosley JD, et al. Phenome-wide association studies demonstrating pleiotropy of genetic variants within FTO with and without adjustment for body mass index. Front Genet 2014;5:250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Campbell PG, Malone J, Yadla S, Chitale R, Nasser R, Maltenfort MG, et al. Comparison of ICD-9-based, retrospective, and prospective assessments of perioperative complications: assessment of accuracy in reporting. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;14(1):16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, Paik JM, Srishord M, Fukui N, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2019;71(4):793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nadkarni GN, Gignoux CR, Sorokin EP, Daya M, Rahman R, Barnes KC, et al. Worldwide frequencies of APOL1 renal risk variants. N Engl J Med 2018;379(26):2571–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369(23):2183–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jostins L, Barrett JC. Genetic risk prediction in complex disease. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20(R2):R182–R188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bunnik EM, Janssens AC, Schermer MH. Personal utility in genomic testing: is there such a thing? J Med Ethics 2015;41(4):322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol 2017;67(4):829–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.