Abstract

Background: Parents of seriously ill children are at risk of psychosocial morbidity, which may be mitigated by competent family-centered communication and role-affirming conversations. Parent caregivers describe a guiding desire to do a good job in their parenting role but also depict struggling under the intense weight of parental duty.

Objectives and Design: Through this case study, the Communication Theory of Identity (CTI) provides a framework for conceptualizing how palliative care teams can help parents cope with this reality. CTI views communication with care teams as formative in the development and enablement of parental perceptions of their “good parenting” role.

Results: Palliative care teams may consider the four frames of identity (personal, enacted, relational, and communal) as meaningful dimensions of the parental pursuit to care well for an ill child.

Conclusion: Palliative care teams may consider compassionate communication about parental roles to support the directional virtues of multilayered dynamic parental identity.

Keywords: case report, communicated theory of identity, communication, pediatric palliative care

Case Description

Toby is a 16-year-old boy with recurrent Ewing's Sarcoma. Toby's dad, Jacob, utilized all his family medical leave earlier in the year to accompany Toby to chemotherapy and radiation appointments. Jacob, a single dad, returned to work two months ago to maintain the health insurance coverage for Toby's ongoing care. Jacob calls Toby's nurse each morning and afternoon for updates and spends the nights with Toby at the hospital. Toby's intensive care room decorations include photographs of father and son playing baseball, eating ice cream, fishing, and camping. The family recently learned that Toby now has lung metastasis and although there is a Phase 1 trial available, it would require transfer to a hospital out of state. In meeting with the palliative care team about care options, Jacob states: “I just want to be a good dad to Toby. What is a good dad supposed to do?”

Introduction

This story captures the challenges of parents of children with serious illness who, themselves, are at risk of significant stress and distress.1 Parents struggle with the weight of their sense of parental duty in the context of their child's heavy medical needs.2 A descriptive study of 118 parents of children receiving care in the pediatric intensive care unit revealed half of parents have symptoms indicative of major depression and one-quarter of parents have significant decisional conflict, although these were mitigated by social support and family-centered communication.3 Human connection, including a recognition of family member roles, is a crucial support mechanism for parents of seriously ill children.4 In particular, bereaved parents recognize memories of communication with their child's care providers, which honored parental identity and the parent's relationship with the child as the most supportive form of communication.5

Parents repeatedly affirm that their guiding goal is to be the best parent they can be to their loved child.6 Parents recognize a hard felt impact of having a seriously ill child with the direct outcome of a strong awareness of the deeply personal unique definition each parent carries of “being a good parent” to the ill child. Parents have shared that their internal “good parent” definition is very much affected by their interpersonal interactions with the ill child's care team. This case report focuses on how pediatric palliative care teams can communicate with parents in ways that support their personal identity as a “good parent.”7,8

The “good parent” construct is not yet embedded within a larger theory or placed within a context of an established theory.9 The advantage of placing this initial parental construct within a larger theory include being able to ask more and different questions that are theory guided. This case report explores the fit of the Good Parent Beliefs Construct within the Communication Theory of Identity (CTI) with consideration of clinical application.

Honoring Parental Roles

Palliative teams looking to support parents of chronically and critically ill children should focus on the ways parents personally describe their parenting relationship with their child and parenting roles. The behaviors of and communication from health care team members can support parents' ability to live into a personal “good parenting” definition.10 An extensive research base has explored the ways that Good-Parent Beliefs impact parental identity, support parental coping, influence family relationships, guide decision making, and affect bereavement.7,10–12 Decisional conflict in medical care or ethics consults are more likely to arise when there are communication gaps, including misunderstanding about parental sense of duty and family values.13,14 Parental sense of decision making for their child may be “rooted more firmly in emotion and perception and ‘desire to be a good parent to a child’ than in medical facts.”15 A communication approach that fosters parents sharing their definition of “good parenting” with trusted care team members at key time points in a child's care (times surrounding diagnosis, key medical decisions, and meaningful changes in clinical status) has potential to improve parental perceptions about their own roles, quality of communication, and parental psychosocial well-being.9

The Communication Theory of Identity

Communication strategies and guides are essential in palliative care. Palliative care teams may consider adding to their existing communication frameworks in caring for parents of critically ill children. One such framework may be provided by the Communication Theory of Identity (CTI). CTI predicts that “our identities emerge in social interaction and are meaningful and influence how we communicate.”16 CTI upholds the idea that “when we talk with others we are, in a sense, performing our identity.”17 Thus, investing the time within the context of a therapeutic relationship with a parent to inquire about their sense of parental identity, family roles, and goals is an impactful moment. Palliative care team members gently and humbly asking a parent to describe her sense of parental roles and her fears or hopes about these parental roles is not just a talking moment. The exchange actually serves to honor the ongoing development and formation of parental relational identity, a multilayered identity that changes and shifts during and after a child's illness. This also empowers parents to make sense of competing goals and enables collaborative decision making between the family and the care team.

CTI is grounded in the idea that identity is co-created in relationships with others and identity emerges in communication.18 Using the lens of CTI, parental role identity comes into existence through communication. Thus, a communication intervention that fosters parents sharing reflections about their relationship with their child actually impacts the formation of parental identity. CTI focuses on mutual influences between identity and communication.19 The co-conceptualization of identity and communication helps palliative teams recognize parental identity is formed and enabled through caring communication.

Defining the Frames of Parental Identity

Conceptually, CTI defines four frames of identity: (1) personal frame that involves how individuals conceptualize themselves and feel about themselves (parent's self-concept), (2) enacted frame that represents the behaviors parents engage in or the decisions parents make that layer parental identity (parent's communication with the care team on behalf of a child's needs), (3) relational frame that involves defining self in terms of roles (parent to ill child) and social interactions with others (parent updating co-parent on child's condition), and (4) communal frame that represents social norms and society's ascription of a collective identity (parent as member of parent support group). Table 1 offers a consideration of these four frames as related to communication with the child's palliative care team.

Table 1.

Frames of Parental Identity in Context of Palliative Care Team Communication

| Identity layer exemplary quote | Definition | Description | Defining inquiry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal layer | How individuals define themselves as parents of a child with serious illness | Self-image, feelings about self, and self-concept | How does the parent define herself in a broad sense and in the context of parenting a seriously ill child? |

| “I am a good parent to my child” | |||

| Enacted layer | How parents experience communication and express social behavior | Identity formed in social interactions and communication exchanges | How does the timing, context, tone, and content of conversations with the palliative team impact the experience of parental identity formation? |

| “The way the palliative team included me in decision-making reinforces my sense of being a good advocate for my child” | |||

| Relational layer | How communication within and across relationships impacts parental identities | Social interaction, relationships with others, and relational identity | How does the nature of the relationship with the child's palliative team influence the parent's identity with the child, the other family members, and the medical team? |

| “The inclusion of my co-parent in palliative care meetings fosters our relationship with each other, our child, and the care team” | |||

| Communal layer | How collectivity, cultural practices, and group dynamics impact parental identity | The collective and normative agreement about what defines good parenting | How does society's ascription of parenting and the medical team's normative perspective on parenting impact parental identity? |

| “The provision of a family leave policy which allows flexible working hours allowed me to meet the expectations of being a present parent” |

Relationships between Frames of Parental Identity

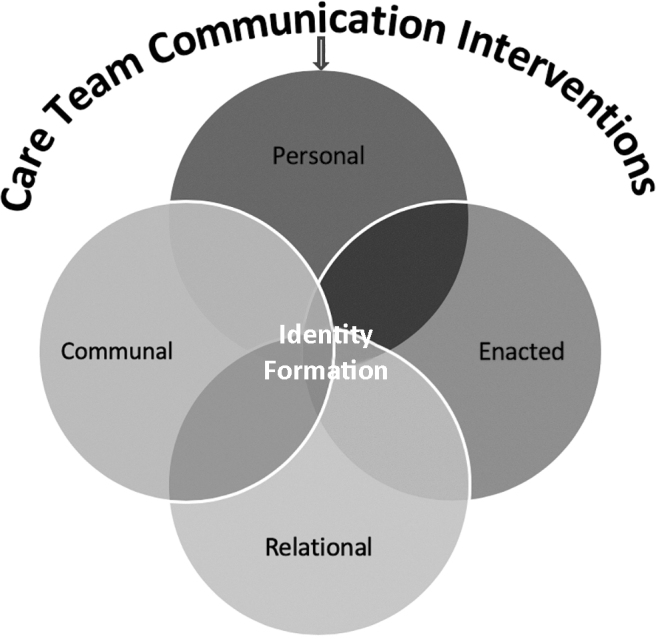

The four frames of identity defined by CTI are inter-related rather than independent, even to the extent that the term “interpenetration” has been applied (Fig. 1).20 A parent's personal identity of how he or she relates to the ill child and makes decisions on behalf of the ill child cannot be discussed without considering how the parent's culture or community defines parental identity. Even how the medical team views parental identity impacts a parent's identity as a parent, such as whether the hospital provides space for parents near the child's hospital bed, whether parents are invited to participate in medical rounds each morning, and the level of parental hands-on care of the child fostered by the medical team. A palliative care team may consider how the hospital culture has defined “good parenting” and how this may cause either supportive benefit or judgment burden for parents.

FIG. 1.

Communicated theory of identity conceptual model.

Recognizing Gaps within Parental Identity

Inconsistency or discrepancy among or between the four layers of identity is real for parents, termed “identity gaps” by CTI.19 Identity gaps result from dissonant beliefs and practices (such as personal and relational identities may feel dissonant or personal and enacted identities may be in conflict). An example of an “identity gap” for Jacob included his definition of “being a good dad” as staying near Toby physically (paternal relational identity) in conflict with his perception of a duty to financially provide for Toby through employment that required working in a location away from Toby's hospital room (paternal provider enacted identity). CTI encourages identifying “identity gaps” to acknowledge and address perceived role conflict. The palliative care team helped Jacob explore and understand the good intention he brings to the various layers of his fatherly identity to try to help him feel less role conflict. The palliative team offered to play voice recordings of Jacob reading to Toby in Toby's room to represent a virtual presence, to coordinate Toby's hands-on medical cares timed in a way to enable Facetime calls between father and son during Jacob's work breaks, and to affirm Jacob's love for Toby to his son when Jacob cannot be physically present. The palliative care team helped Jacob address his sense of “identity gap” by together recognizing with him the ways that he is physically present for Toby and also providing for Toby.

For some parents, “identity gaps” may occur when the family's public image within a large extended family or a support group is established in a way that feels less congruent with the family's evolving goals as the child's treatment trajectory changes. A visual example would be wearing “Cancer Fighters” family T-shirts initially but when curative-directed options narrow, this type of bold public identity becomes historic compared with the quieter priority of comfort.

Palliative Team Communication Fostering Positive Parental Identity

CTI lends itself to communication interventions by recognizing the parents of an ill child not just as stagnant unidimensional “parent to child in Room 218” but as multilayered vibrant individuals possessing multiple layers of identity. When a trusted member of the palliative care team gently asks about personal, relational, enacted, and communal identities that parents may be experiencing either compatibly or in conflict; palliative care teams may then better understand ways to support the parenting experience. Suggested ways for this inquiry have included the open-ended question: “How do you define your role as a parent?” and “How can your child's care team best support you in your parental role?”.9 CTI considers these role-defining questions foundational to both communication support and identity formation.

Communication builds, sustains, and modifies parent identity. CTI honors the idea of communication about parental identity impacting parental relationships with the self, with the ill child, and even with the child's care team. Sometimes palliative teams underappreciate the parent's relational identity with the palliative team members as part of their overall sense of parenting identity. When humble and curious care team members invest the time and energy to communicate with parents about ways to support the parental role even in times of decisional conflict, parents receive benefit to their parental identity. Parents describe the encouragement and affirmation of their parental role by care team members as sustaining and identity affirming.21,22 According to CTI, communication with the palliative team may be co-forming parental identity. Benefits to the medical team include better understanding of potential parental role conflicts, improved capacity to identity gaps in care, and insight into ways to provide personalized family care.

Conclusion

Toby's palliative care team, known to Toby and Jacob for many years, responded to Jacob's questions by humbly asking Jacob “How do you define being a good dad to Toby?” Jacob was able to share his personal definition as “being there for Toby even on the hard days, allowing Toby to share his preferences and trying to respect his preferences, always showing Toby I love him, and being strong for my son.” The palliative team offered to support Toby and Jacob sharing their personal preferences together in an interdisciplinary family care conference. Before the family meeting, the chaplain and social worker met with Jacob and Toby individually to review their personal hopes, fears, and goals in preparation for sharing with one another. Toby expressed wanting to go home, to be with his dad and dog, and to make more memories with Jacob. The team worked together with Toby and Jacob to ensure that symptom support would be in place in the home setting and helped to transition Toby home. The child life specialist worked with Toby to create a “What I Love Most About My Really Amazing Dad” picture poster, which the team provided to Jacob as a legacy gift three months later when Toby reached a natural end of life at home in the arms of his father. In bereavement, Jacob remains able to voice his sense of pride in having been a good and loving parent.

Ultimately, parents of seriously ill children want and need to know that they are parenting their loved child well. Parents possess multiple layers of parental identities, including their interpersonal relationship when communicating with their child's palliative care team. CTI offers an exploratory framework to help parents' identity their dynamic multifaceted parental identities through personal, relational, enacted, and/or communal lenses. CTI may help palliative care team members foster parental goals of obtaining their desired “good parent” identity by communicating supportively about parental hopes, identity gaps, and roles.

Funding Information

NIH NINR R01NR015831 (Hinds, PI). How Parent Constructs Affect Parent and Family Well-Being after a Child's Death.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, et al. : Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2004;5:547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abela KM, Wardell D, Rozmus C, LoBiondo-Wood G: Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: An updated systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs 2019;51:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stremler R, Haddad S, Pullenayegum E, Parshuram C: Psychological outcomes in parents of critically ill hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs 2017;34:36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Madrigal VN, Kelly KP: Supporting family decision-making for a child who is seriously ill: Creating synchrony and connection. Pediatrics 2018;142(Suppl 3):S170–S177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sedig LK, Spruit JL, Paul TK, et al. : Experiences at the end of life from the perspective of bereaved parents: Results of a qualitative focus group study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;30:1049909119895496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feudtner C, Schall T, Hill D: Parental personal sense of duty as a foundation of pediatric medical decision-making. Pediatrics 2018:142:S133–S141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robinson J, Huskey D, Schalley S, et al. : Discovering dad: Paternal roles, responsibilities, and support needs as defined by fathers of children with complex cardiac conditions perioperatively. Cardiology Young 2019;29:1143–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hill DL, Faerber JA, Li Y, et al. : Changes over time in good-parent beliefs among parents of children with serious illness: A two-year cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weaver M, October T, Feudtner C, Hinds P: ‘Good-Parent Beliefs': Research, Concept, and Clinical Practice. Pediatrics 2020;145:e20194018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. : “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5979–5985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, Hinds PS: The parent perspective: “being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15:291–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. : Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winter MC, Friedman DN, McCabe MS, Voigt LP: Content review of pediatric ethics consultations at a cancer center. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66:e27617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morrison W, Womer J, Nathanson P, et al. : Pediatricians' experience with clinical ethics consultation: A national survey. J Pediatr 2015;167:919–924 e911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bennett RA, LeBaron VT: Parental perspectives on roles in end-of-life decision making in the pediatric intensive care unit: An integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs 2019:46:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jung E, Hecht ML: Elaborating the communication theory of identity: Identity gaps and communication outcomes. Commun Q 2004;52:265–283 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hecht ML, Lu Y: Communication theory of identity. In: Thompson TL (ed): Encyclopedia of Health Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hecht ML: 2002—A research odyssey: Toward the development of a communication theory of identity. Commun Monogr 1993;60:76–82 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hecht ML, Hopfer S: The communication theory of identity. In: Jackson RL. (ed): Encyclopedia of Identity, vol. 1 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010, pp. 115–119 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hecht ML: Communication theory of identity: Multi-layered understandings of performed identities. In: Braithwaite DO, Schrodt P (eds). Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015, pp. 175–188 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rennick JE, St-Sauveur I, Knox AM, Ruddy M: Exploring the experiences of parent caregivers of children with chronic medical complexity during pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: An interpretive descriptive study. BMC Pediatr 2019;19:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wigert H, Dellenmark Blom M, Bry K: Parents' experiences of communication with neonatal intensive-care unit staff: An interview study. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]