Abstract

Background: Chaplain-led communication-board-guided spiritual care may reduce anxiety and stress during an intensive care unit (ICU) admission for nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients, but clinical pastoral education does not teach the assistive communication skills needed to provide communication-board-guided spiritual care.

Objective: To evaluate a four-hour chaplain-led seminar to educate chaplains about ICU patients' psychoemotional distress, and train them in assistive communication skills for providing chaplain-led communication-board-guided spiritual care.

Design: A survey immediately before and after the seminar, and one-year follow-up about use of communication-board-guided spiritual care.

Subjects/Setting: Sixty-two chaplains from four U.S. medical centers.

Measurements: Multiple-choice and 10-point integer scale questions about ICU patients' mental health and communication-board-guided spiritual care best practices.

Results: Chaplain awareness of ICU sedation practices, signs of delirium, and depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder in ICU survivors increased significantly (all p < 0.001). Knowledge about using tagged yes/no questions to communicate with nonvocal patients increased from 38% to 87%, p < 0.001. Self-reported skill and comfort in providing communication-board-guided spiritual care increased from a median (interquartile range) score of 4 (2–6) to 7 (5–8) and 6 (4–8) to 8 (6–9), respectively (both p < 0.001). One year later, 31% of chaplains reported providing communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU.

Conclusions: A single chaplain-led seminar taught chaplains about ICU patients' psychoemotional distress, trained chaplains in assistive communication skills with nonvocal patients, and led to the use of communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU for up to one year later.

Keywords: chaplaincy, critical care, mechanical ventilation, palliative care, spiritual therapies

Introduction

Advances in critical care have led to an increased number of patients receiving mechanical ventilation while awake in the intensive care unit (ICU).1,2 Awake and nonvocal patients may have unmet palliative and spiritual care needs, and are at high risk for depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after hospital discharge.3–5

Spirituality and religion are integral in helping patients cope with illness,6 with the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine listing spiritual care as an essential component of palliative care for critically ill patients.7,8 In the ICU, chaplains address spiritual and religious needs of patients and their families, but they are usually consulted for dying patients and interact primarily with families.4 Chaplains remain underutilized for patients who may have considerable psychoemotional and spiritual distress while receiving mechanical ventilation or other intensive care,4 and for the majority of ICU patients who ultimately survive.9

The classical approach to clinical pastoral care involves assessing spiritual or religious affiliation, emotions, spiritual pain, and/or desired chaplain interventions through vocal conversation with a patient.10 Formal clinical pastoral education (CPE) focuses on personal growth, introspection, and exploration of the trainee's religious background,11 and emphasizes experience in providing spiritual care as the primary learning source. Although common standards and competencies in chaplaincy have been recently developed,12 there is not yet any standardized curriculum for CPE. Therefore, chaplains usually acquire the spiritual care skills needed to treat patients through practical experience and interaction with peers during a chaplaincy residency, and through independent study.13

We previously conducted a single center single chaplain study at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. We demonstrated that chaplain-led spiritual care using a picture-based communication board is feasible among mechanically ventilated adult patients (Fig. 1), and shows potential for reducing anxiety during and stress after an ICU admission.14 The chaplain who developed this novel communication-board-guided spiritual care did so through his independent study of communication disorders science, and through his interactions with ICU physicians and nurses. Currently, CPE does not include formal training to identify and treat ICU patients who are communication-impaired, and who might benefit from communication-board-guided spiritual care.10

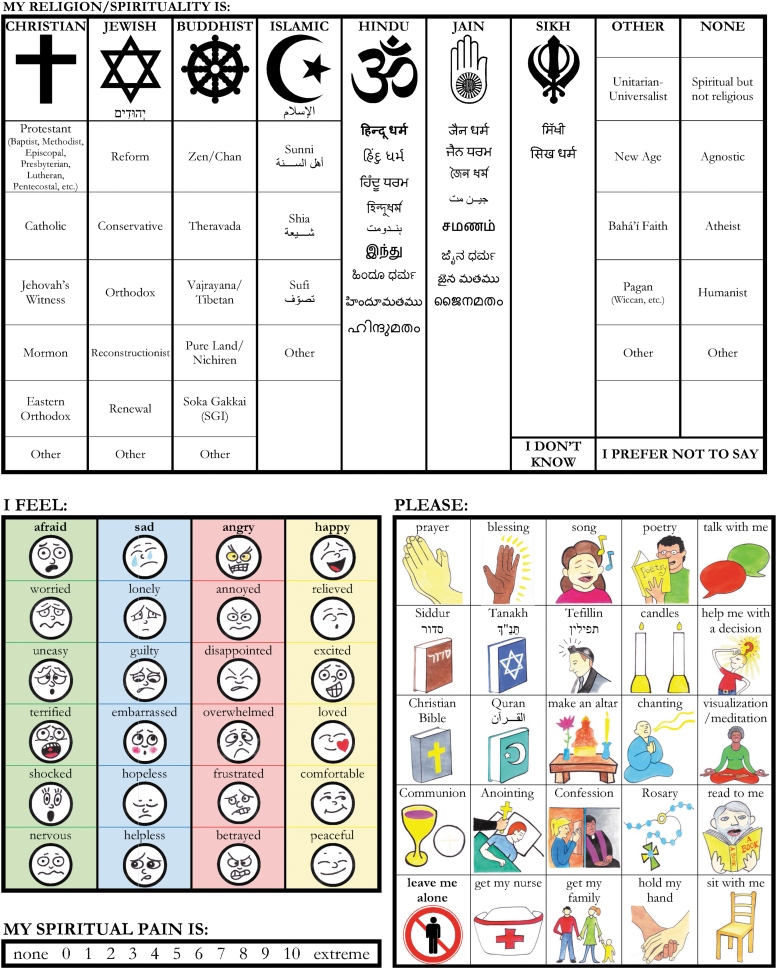

FIG. 1.

Picture-based spiritual care communication board. Front side: Part 1: spiritual/religious affiliation assessment. Back side. Part 2: feelings assessment. Part 3: spiritual pain assessment. Part 4: chaplain interventions. The communication board is 28 × 43 centimeters and laminated.

The overarching goal of this multicenter study was to evaluate a four-hour chaplain-led training seminar to educate chaplains about ICU patients' psychoemotional distress and teach them essential assistive communication skills for providing communication-board-guided spiritual care to communication-impaired ICU patients.14 We hypothesized that chaplains' self-reported knowledge of ICU patients' mental health problems and their skill and confidence in being able to communicate with nonvocal ICU patients would increase after the training seminar.

Methods

Study design, subjects, and setting

We conducted a survey study to evaluate a four-hour chaplain-led training seminar. Based on his prior research and presentations at national chaplaincy meetings,14 the chaplain instructor was invited to four academic medical centers (Baylor University, University of Kentucky, Stanford University, and the University of California San Francisco [UCSF]) to teach other chaplains about communication-board-guided spiritual care. Chaplains from each medical center were invited to the seminar training and voluntarily participated in taking the survey. At UCSF, participants included chaplains from nearby Saint Francis Memorial Hospital and California Pacific Medical Center. Chaplain experience ranged from intern (enrolled in a 400-hour unit of training) and resident (employed for a year of more advanced training) to board-certified chaplain. Surveys were administered to chaplains immediately before and after the seminars, which took place between May and October of 2018. Surveys included multiple-choice and 10-point integer scale questions regarding mental health effects after an ICU admission, communication-board-guided spiritual care best practices, skill and comfort with providing communication-board-guided spiritual care, and open-ended questions about other patient populations that could potentially benefit from communication-board-guided spiritual care.

Approximately one year later, in August 2019, we contacted the chaplain from each medical center who helped organize the seminar training. We asked each of them about (1) barriers to implementing chaplain-led communication-board-guided spiritual care; (2) whether chaplains performed a delirium assessment; and (3) the number of resident and staff chaplains currently using the spiritual care communication board for chaplain consults in the ICU. All chaplain survey respondents provided informed consent. Seminar survey results were anonymized using Qualtrics software (Provo, Utah, USA). The study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (protocol #AAAR3950).

Training seminar on communication-board-guided spiritual care

The seminar included education concerning the rationale for communication-board-guided spiritual care, mental health challenges faced by critically ill patients, and practical knowledge regarding implementation of spiritual care in the ICU. In terms of the rationale, chaplains were educated on three key elements: (1) minimization of sedation in ICU patients is associated with improved survival and less post-ICU disability15,16 and has become an ICU best practice, resulting in many mechanically ventilated patients who are interactive and delirium free17; (2) about half of awake alert mechanically ventilated ICU patients rate spiritual pain >5 on a 10-point integer scale14; (3) being nonvocal is the most common stressful experience reported by mechanically ventilated patients,18 and many care providers may limit their communication with these nonvocal patients.19–21 Chaplains were also educated about ICU delirium and how it may impede spiritual care, and that ICU survivors have a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and PTSD compared with the general population.5,22

In terms of implementing communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU, the chaplains were taught to assess patients' ability to communicate by considering the type of mechanical ventilation (endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation), whether patients were receiving opioid, benzodiazepine, or other anesthetic infusions, and by working with the ICU care team to assess patient alertness with the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) and delirium with the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)-ICU. Chaplains were then taught the following process to provide spiritual care to nonvocal ICU patients: (1) Before the visit, review the medical record to ascertain the patient's diagnoses and prognosis (including reviewing notes from psychiatry/psychology, social work, palliative care, speech pathology, and other chaplains); (2) ask whether the patient can hear and understand you, and whether the patient is having trouble hearing and understanding you; (3) use the spiritual care communication board as a supplement with another communication method, such as mouthing (reading the patient's lips), writing (with a felt-tip pen, on a dry erase board or clipboard), and/or conversation using “tagged yes/no questions” (i.e., a question followed by a “yes?” or “no?” with up then down voice modulation); and (4), after using the spiritual care communication board, leave the board with the patient to prevent nosocomial transmission of infection.

Statistical analyses

We present continuous data using median (interquartile range [IQR]), and categorical data using percentages. We compared pre- and postseminar training 10-point integer scale question scores using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and categorical responses using McNemar's test. Statistical significance was defined as p-value <0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Sixty-two of the 66 chaplains (94%) who attended the seminar completed surveys immediately before and after the seminar (8 from University of Kentucky, 23 from Baylor University, 21 from UCSF, and 10 from Stanford University).

ICU patient cognition and mental health knowledge

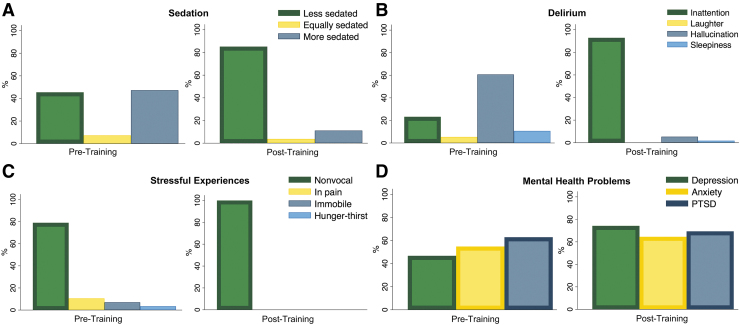

Surveys revealed that chaplains learned about important aspects of ICU patients' cognition and mental health that they had little knowledge about before the seminar training. Pretraining, 45% of chaplain respondents knew that ICU patients tend to be less sedated than in years past, but 8% and 47% incorrectly thought that ICU patients now tend to be just as sedated or more sedated, respectively. Knowledge that minimized sedation is now an ICU best practice increased to 85% post-training (p < 0.001). Pretraining, 61% incorrectly reported hallucinations to be the cardinal sign of delirium. Post-training, knowledge that delirium is primarily characterized by inattention increased from 23% to 93% (p < 0.001). Knowledge that being nonvocal is the most commonly reported stressful experience of mechanical ventilation survivors increased from 79% to 100% (p < 0.001). Awareness that the prevalence of depression among ICU survivors is higher than the general population increased significantly from 47% to 74% (p < 0.001). Awareness that post-ICU anxiety and PTSD prevalence is higher in ICU survivors compared with the general population increased nonsignificantly from 55% to 65% (p = 0.18), and from 63% to 69% (p = 0.43), respectively (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Bar graphs show the proportion of respondent answers to multiple choice questions from a pre- and post-training assessment. Correct answers are indicated by a thick border. (A) Chaplains were asked to identify how sedation practices have changed over the past decade in the ICU, and knowledge that patients are less sedated increased from 45% to 85%, p < 0.001. (B) Chaplains were asked to identify the cardinal sign of delirium, and knowledge that delirium is primarily characterized by inattention increased from 23% to 93%, p < 0.001. (C) Chaplains were asked to identify the most common stressful experience reported by mechanically ventilated patients, and knowledge that being nonvocal is the most commonly reported stressful experience increased from 79% to 100%, p < 0.001. (D) Chaplains were asked to identify which mental health problem(s) have a higher prevalence among survivors of mechanical ventilation compared with the general population. Knowledge that depression is higher increased significantly (47% to 74%, p < 0.001), that PTSD is higher increased nonsignificantly (63% to 69%, p = 0.43), and that anxiety is higher increased nonsignificantly (55% to 65%, p = 0.18). Percentages in (D) add up to >100% since respondents could select more than one answer. ICU, intensive care unit; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Assistive communication skills knowledge

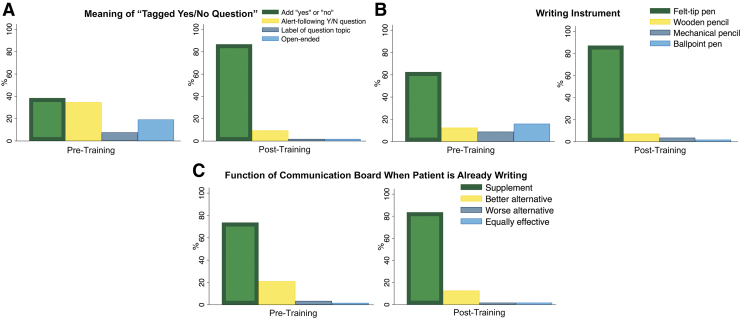

Surveys revealed that chaplains learned about assistive communication skills that they had little to no knowledge of before the seminar training. Chaplain knowledge about using “tagged yes/no questions” for nonvocal ICU patients increased from 38% to 87% (p < 0.001). Chaplains were asked to identify the best writing instrument for an ICU patient. A majority already knew that felt-tip pens were best (63%), but this knowledge still increased significantly post-training (87%, p < 0.001). Chaplains were asked about the utility of a communication board if an ICU patient is able to write legibly, and knowledge that a communication board should still be used to supplement writing increased nonsignificantly from 74% to 84% (p = 0.21) (Fig. 3). Knowing that the board should be left with the patient to prevent nosocomial infection transmission increased from 34% pretraining to 89% post-training (p < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Bar graphs show the proportion of respondent answers to multiple choice questions from a pre- and post-training assessment. Correct answers are indicated by a thick border. (A) Chaplains were asked to identify the meaning of a “tagged yes/no question,” and knowledge that this means “an added ‘yes or no’ to the end of a question” increased from 38% to 87%, p < 0.001. B) Chaplains were asked to identify the best writing instrument for an ICU patient. Knowledge that felt-tip pens were best increased from pre- to post-training (63% to 87%, p < 0.001). (C) Chaplains were asked about the utility of a communication board if an ICU patient is able to write legibly. Knowledge that a communication board should be still be used to supplement writing increased nonsignificantly (74% to 84%, p = 0.21).

Skill and comfort with communication-board-guided spiritual care

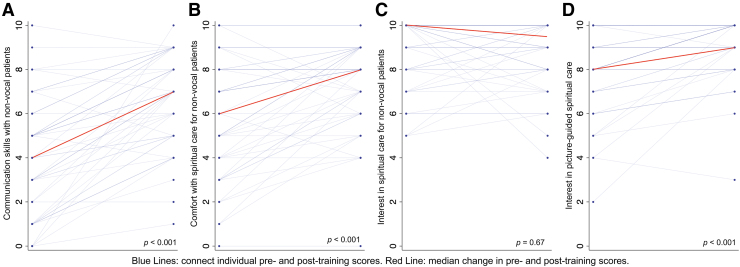

Self-reported levels of skill and comfort in providing spiritual care to nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients increased significantly from a median (IQR) score of 4 (2–6) to 7 (5–8) and 6 (4–8) to 8 (6–9), respectively (both p < 0.001). Interest in using the spiritual care communication board increased significantly from 8 (7–10) to 9 (8–10) (p < 0.001). Median (IQR) rated interest in providing spiritual care to nonvocal ICU patients on mechanical ventilation was initially 10 (8–10) and decreased nonsignificantly to 9.5 (8–10) (p = 0.67). Five chaplains (10%) reported less comfort and 11 chaplains (21%) reported less interest in providing spiritual care to nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients post-training, with a median (IQR) decrease of 2 (2–3) points and 2 (1–3) points, respectively (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Self-reported rankings on a 10-point integer scale were collected from chaplains pre- and post-training. (A) Level of assistive communication skills in providing spiritual care to awake nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients increased from a median (IQR) score of 4 (2–6) to 7 (5–8), p < 0.001. (B) Level of comfort with providing spiritual care to awake nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients increased from a median (IQR) score of 6 (4–8) to 8 (6–9), p < 0.001. (C) Level of interest in providing spiritual care to awake nonvocal mechanically ventilated patients decreased marginally from a median (IQR) score of 10 (8–10) to 9.5 (8–10), p = 0.67. (D) Level of interest in integrating a communication-board-guided spiritual care into chaplaincy increased from a median (IQR) score of 8 (7–10) to 9 (8–10), p < 0.001. IQR, interquartile range.

Communication-board-guided spiritual care for other patients

Thirty-eight chaplains (61%) provided written suggestions about other patient populations that could potentially benefit from communication-board-guided spiritual care. Analysis revealed eight patient categories: (1) neurological patients, including those with stroke, dementia, aphasia, autism spectrum disorder, and traumatic brain injury (39% of respondents); (2) hearing impaired patients (37% of respondents); (3) pediatric patients (34% of respondents); (4) psychiatric patients, including those with depression (34% of respondents); (5) ear, nose, and throat surgery patients (26% of respondents); (6) patients with limited English proficiency (26% of respondents); (7) nonvocal patients outside the ICU (21% of respondents); and (8), the elderly (8% of respondents).

One-year follow-up

At one-year follow-up, 31% of resident and staff chaplains working in ICUs reported using communication-board-guided spiritual care (University of Kentucky 35%, Baylor 27%, Stanford 39%, and UCSF 22%). At follow-up, chaplains reported three barriers to utilizing the spiritual care communication board: (1) poor accessibility of the boards, since many reported that boards are kept in the chaplains' office rather than in the ICU; (2) the cost of purchasing boards for each patient, since boards should not be used with multiple patients to prevent nosocomial infection transmission; and (3), patient difficulty with using the communication board, including inability to point to the board due to neuromuscular weakness, or inattention and lack of understanding about the pictures on the board. At all four centers, chaplains never assessed delirium themselves, but used ICU nurse or clinician delirium assessments documented in the electronic medical record, or asked ICU staff to identify mechanically ventilated patients who might be able to participate in communication-board-guided spiritual care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chaplain Participants in Training Seminar for Communication-Board-Guided Spiritual Care in the Intensive Care Unit

| Kentucky | Stanford | Baylor | UCSF | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff and resident chaplains attended training seminar,an | 8 | 10 | 27 | 21 | 66 |

| Completed surveys, n (%) | 8 (100) | 10 (100) | 23 (85) | 21 (100) | 62 (94) |

| One-year follow-up | |||||

| Staff chaplains working in ICUs, n | 10 | 9 | 13 | 3 | 35 |

| Staff chaplains using communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU, n (%) | 4 (40) | 2 (22) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 9 (26) |

| Resident chaplains working in ICUs, n | 7 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 40 |

| Resident chaplains using communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU, n (%) | 2 (29) | 5 (56) | 3 (33) | 4 (27) | 14 (35) |

| Total chaplains working in ICUs, n | 17 | 18 | 22 | 18 | 75 |

| % Staff and resident chaplains using communication-board-guided spiritual care in the ICU, n (%) | 6 (35) | 7 (39) | 6 (27) | 4 (22) | 23 (31) |

Individual level of training was not ascertained to ensure survey anonymity.

ICU, intensive care unit; UCSF, University of California San Francisco.

Discussion

We have shown that a single chaplain-led training seminar increases chaplains' knowledge and skills to deliver communication-board-guided spiritual care to nonvocal ICU patients. Pretraining results revealed major gaps in chaplain knowledge about ICU patients' cognition and mental health, and about assistive communication techniques. Post-training results demonstrated significant increases in understanding about various facets of ICU patients' cognition and psychoemotional distress, and self-reported comfort and skill in providing communication-board-guided spiritual care to nonvocal ICU patients. After this single training seminar, 31% of chaplains reported using communication-board-guided spiritual care in their ICU spiritual care practice one year later. This four-center study provides external validation that chaplain-led communication-board-guided spiritual care in mechanically ventilated patients can be taught and provided beyond our single center where it was first developed and tested.14

A few chaplains reported less comfort with communication-board-guided spiritual care after the seminar, and one year after the training, only one-third of chaplains at participating medical centers had adopted communication-board-guided spiritual care into their practice. Therefore, chaplains may benefit from a more comprehensive and multimodal assistive communication training approach to facilitate uptake of communication-board-guided spiritual care. The Study of Patient–Nurse Effectiveness with Assisted Communication Strategies-2 (SPEACS-2) program that was developed for ICU nurses is one such comprehensive and multimodal program that has been shown to improve the ease of communication between nurses and patients in the ICU.23,24 SPEACS-2 consists of a one-hour web-based video training in communication assessments, providing nurses with a pocket guide algorithm for evaluating assistive communication strategies, providing nurses with an ICU communication cart that includes communication boards, dry erase boards with felt-tip pens, and magnifying glasses and hearing amplifiers for patients, and training nurses to consult speech language pathologists to assist with optimizing communication strategies for their nonvocal patients.23,24 Adapting aspects of the SPEACS-2 program for chaplains, such as creating a preseminar web-based training in communication assessment, providing chaplains with a pocket guide algorithm for assessing assistive communication strategies, and encouraging consultation with a speech language pathologist to assist with optimizing assistive communication techniques could further improve adoption and maintenance of communication-board-guided spiritual care.

At one-year follow-up, chaplains identified lack of storage space of communication boards in or near the ICU, lack of available funds to purchase communication boards for each ICU patient they consulted on, and consulting on reportedly awake and alert patients who were still inattentive. These barriers to communication-board-guided spiritual care broadly reflect the fact that chaplains are not yet integrated as core members of the ICU care team. Prior ICU chaplaincy research has shown that clinical triggers for chaplaincy consultation are lacking, that there is debate about who should screen for chaplaincy need, and that chaplaincy service is primarily reserved for dying patients and their families rather than proactively provided as patient-centered spiritual support.4,25,26 Even though ICU clinicians report a self-perceived role in addressing spiritual and religious needs of patients, few actually provide spiritual care, and many lack an understanding of chaplains' roles.9,26 In the ICU, nurses are more likely to consult chaplains than physicians, and chaplains are most likely to interact with nurses after a patient encounter, which reveals a lack of communication between chaplains and ICU physicians.4

To more fully and sustainably implement chaplain-led communication-board-guided spiritual care for ICU patients, multidisciplinary ICU care teams first need to recognize that approximately one half of mechanically ventilated adult patients are awake, alert, and responsive to communication during any given day in the ICU17 and, therefore, may stand to benefit from a chaplain consultation that involves communication-board-guided spiritual care. Second, ICU teams should consider providing the spiritual care communication board to chaplains, similar to how ICU nurses are often provided a communication board to help quantify a patient's level of pain. Creating a centralized ICU communication cart, as was done in the SPEACS-2 ICU communication intervention studies,23,24 that includes communication boards for both nurses and chaplains, as well as dry erase boards with felt-tip pens, and magnifying glasses and hearing amplifiers for patients could substantially improve patients' well-being and satisfaction. Third, ICU physicians and nurses need to develop protocols specific to their workflow to screen for delirium and hold sedating medication daily to identify awake and alert communication-impaired patients who might be interested in receiving communication-board-guided spiritual care with a chaplain.

Our study has limitations. This study occurred at four academic medical centers in the United States and did not include chaplains who practice in community hospitals or in other countries. The training was a four-hour seminar that did not provide any opportunity for chaplains to practice the assistive communication skills that were taught, which may have limited its efficacy. Allowing chaplains to practice with simulated patients (i.e., actors), a training method that has become integral to medical education,27 could be integrated into a future version of this training seminar. Chaplains were taught to use the spiritual care communication board as a supplement with another communication method, such as mouthing, writing, and/or conversation with “tagged yes/no questions.” Although mouthing is one of the commonest unaided communication strategies used by ICU nurses and mechanically ventilated patients,19,28 mouthing is sometimes misinterpreted or uninterpretable by nurses.20 Future study should investigate the efficacy of mouthing versus other assistive communication techniques when used in conjunction with the spiritual care communication board as a conversation guide. We calculated the percentage of chaplains using communication-board-guided spiritual care at one-year follow-up based on the total number of chaplains working in the ICUs at one-year follow-up (n = 75), not based on the number of chaplains who attended the seminar and anonymously completed the pre- and post-training surveys (n = 62). Since chaplain interns hold work assignments of one year or less, some change in group composition likely occurred between the seminar attendees and the chaplains assessed on follow-up. Therefore, although we report the true prevalence of communication-board-guided spiritual care one year later, we likely underestimate the true proportion of chaplain seminar attendees who incorporated communication board spiritual care into their ICU pastoral care practice. We did not measure the quality or effects of communication-board-guided spiritual care, and validation of our previous finding that communication-board-guided spiritual care may reduce anxiety and stress during and after ICU admission is still needed.14

In conclusion, traditional spiritual care education does not yet train chaplains to identify nonvocal ICU patients who could benefit from spiritual care, nor to provide proactive spiritual care to nonvocal ICU patients, despite the fact that these patients experience substantial spiritual and psychoemotional distress while critically ill. Our study suggests that it is feasible to quickly teach chaplains to provide communication-board-guided spiritual care, which may expand their role in the ICU and create new opportunities to provide spiritual care for other communication-impaired patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank those chaplains who organized the seminars and those who participated in one-year follow-up: Lori Klein, Satoe Soga, Lauren Frazier-McGuin, Michael Washington, Chad Mustain, Kathryn Perry, and Will Hocker.

Funding Information

This study was funded by grants K23 AG045560 (MRB) and K08 AG051184 (MH) from the National Institute on Aging. This study was also supported by the Columbia University Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1 TR001873).

Author Disclosure Statement

J.N.B. is partial owner of a copyright for the spiritual care communication board that is licensed to Acuity Medical; I.M.S., M.H., M.B.H., and M.R.B. have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. Zambon M, Vincent JL: Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest 2008;133:1120–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lerolle N, Trinquart L, Bornstain C, et al. : Increased intensity of treatment and decreased mortality in elderly patients in an intensive care unit over a decade. Crit Care Med 2010;38:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldwin MR, Wunsch H, Reyfman PA, et al. : High burden of palliative needs among older intensive care unit survivors transferred to post-acute care facilities. A single-center study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;10:458–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi PJ, Curlin FA, Cox CE: “The Patient is Dying, Please Call the Chaplain”: The activities of Chaplains in One Medical Center's Intensive Care Units. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:501–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM: Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med 2011;39:371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Puchalski C: Spirituality in health: The role of spirituality in critical care. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:487–504, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. : An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:912–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Truog RD, Cist AF, Brackett SE, et al. : Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2001;29:2332–2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi PJ, Chow V, Curlin FA, et al. : Intensive care clinicians' views on the role of Chaplains. J Health Care Chaplain 2019;25:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Association of Professional Chaplains. Standards of Practice in Acute Care 2009; www.professionalchaplains.org/files/professional_standards/standards_of_practice/standards_practice_professional_chaplains_acute_care.pdf (Last accessed July22, 2015)

- 11. Ragsdale JR: Transforming Chaplaincy Requires Transforming Clinical Pastoral Education. J Pastoral Care Counsel 2018;72:58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ford T, Tartaglia A: The development, status, and future of healthcare chaplaincy. South Med J 2006;99:675–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kiesskalt L, Volland-Schussel K, Sieber CC, et al. : [Hospital pastoral care of people with dementia: A qualitative interview study with professional hospital pastoral carers]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2018;51:537–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berning JN, Poor AD, Buckley SM, et al. : A novel picture guide to improve spiritual care and reduce anxiety in mechanically ventilated adults in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1333–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reade MC, Finfer S: Sedation and delirium in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 2014;370:444–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. : Caring for critically Ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: Results of the ICU liberation collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med 2019;47:3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Happ MB, Seaman JB, Nilsen ML, et al. : The number of mechanically ventilated ICU patients meeting communication criteria. Heart Lung 2015;44:45–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khalaila R, Zbidat W, Anwar K, et al. : Communication difficulties and psychoemotional distress in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 2011;20:470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Happ MB, Garrett K, Thomas DD, et al. : Nurse-patient communication interactions in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2011;20:e28–e40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Happ MB, Tuite P, Dobbin K, et al. : Communication ability, method, and content among nonspeaking nonsurviving patients treated with mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2004;13:210–218; quiz 219–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patak L, Gawlinski A, Fung NI, et al. : Patients' reports of health care practitioner interventions that are related to communication during mechanical ventilation. Heart Lung 2004;33:308–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. : Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:796–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trotta RL, Hermann RM, Polomano RC, et al. : Improving nonvocal critical care patients' ease of communication using a modified SPEACS-2 program. J Healthc Qual 2020;42:e1–e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Happ MB, Baumann BM, Sawicki J, et al. : SPEACS-2: Intensive care unit “communication rounds” with speech language pathology. Geriatr Nurs 2010;31:170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. King SD, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, et al. : Determining best methods to screen for religious/spiritual distress. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:471–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi PJ, Curlin FA, Cox CE: Addressing religion and spirituality in the intensive care unit: A survey of clinicians. Palliat Support Care 2019;17:159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bokken L, Rethans JJ, van Heurn L, et al. : Students' views on the use of real patients and simulated patients in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med 2009;84:958–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nilsen ML, Happ MB, Donovan H, et al. : Adaptation of a communication interaction behavior instrument for use in mechanically ventilated, nonvocal older adults. Nurs Res 2014;63:3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]